Introduction

Despite medical advances in recent years, global cancer prevalence and mortality rates and the need for palliative care continue to rise, particularly in lower-resource settings (Connor Reference Connor2020). Although there has been substantial development of palliative care in Africa, there is still limited access to palliative care for individuals in need in many African countries (Rhee et al. Reference Rhee, Garralda and Torrado2017). Further, there has been a paucity of research on the quality of dying and death of Africans with advanced or terminal disease (Hannon et al. Reference Hannon, Zimmermann and Knaul2016).

Uganda and Kenya have been regarded as African leaders in developing palliative care infrastructure and services (Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Powell and Mwangi-Powell2018): Uganda has been rated as having preliminary palliative care integration into mainstream service provision; and Kenya, as having generalized palliative care provision without mainstream integration (Connor Reference Connor2020). These ratings are based on objective criteria, such as affordability of palliative care, integration of palliative care education into health care, and access to pain medication (Connor Reference Connor2020; Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Powell and Mwangi-Powell2018). However, data on the end-of-life experiences of African patients with advanced disease have been lacking. Such data are essential to determine the effectiveness of palliative care services and to inform needed improvements (Dudgeon Reference Dudgeon2018).

The Quality of Dying and Death (QODD) questionnaire (Curtis et al. Reference Curtis, Patrick and Engelberg2002; Patrick et al. Reference Patrick, Engelberg and Curtis2001), the best-validated measure of the quality of dying and death currently available (Hales et al. Reference Hales, Zimmermann and Rodin2010), has been utilized in research in North America (Hales et al. Reference Hales, Chiu and Husain2014), Europe (Gerritsen et al. Reference Gerritsen, Hofhuis and Koopmans2013), Israel (Braun et al. Reference Braun, Hasson-Ohayon and Hales2014), and South America (Pérez-Cruz et al. Reference Pérez-Cruz, Padilla Pérez and Bonati2017). The interview-based questionnaire is administered to proxy raters, most often bereaved caregivers of deceased patients, who are asked to rate retrospectively the patients’ quality of dying and death (Curtis et al. Reference Curtis, Patrick and Engelberg2002). The tool includes 31 content items and 2 single-item ratings of overall quality of dying and moment of death. It assesses 6 conceptual domains: Symptoms and Personal Care, Preparation for Death, Moment of Death, Family, Treatment Preferences, and Whole Person Concerns (Patrick et al. Reference Patrick, Engelberg and Curtis2001). In factor-analytic research, a truncated version of the measure was generated with 4 empirical domains: Symptom Control, Preparation, Connectedness, and Transcendence (Downey et al. Reference Downey, Curtis and Lafferty2010).

We previously compared the quality of dying and death of patients with advanced cancer who had received care in Kenyan hospices to that of patients in Ontario, Canada, by comparing the 2 groups on the QODD’s individual items (Mah et al. Reference Mah, Powell and Malfitano2019b). Similarly, we investigated the quality of dying and death of patients with advanced cancer who had received care in Ugandan hospices by examining the QODD item ratings (Mah et al. Reference Mah, Namisango and Luyirika2023). To identify region-specific challenges and opportunities to improve end-of-life care, it may be of greater value to compare general domains of quality of dying and death between countries that are geographically and socioeconomically similar (Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Powell and Mwangi-Powell2018). The present observational study aimed to compare domains of quality of dying and death in Uganda and Kenya in patients with advanced cancer who had received hospice care in either country. Based upon their rated palliative care development levels, we hypothesized that Ugandan caregivers would report better overall and domain-specific quality of dying and death than Kenyan caregivers.

Methods

Participants

Participants were primary caregivers of deceased patients with advanced cancer who had received hospice-based palliative care at either Hospice Africa Uganda or Kitovu Mobile Hospice in Uganda or at Eldoret, Nairobi, or Nyeri Hospices in Kenya. Inclusion criteria for the study were caregivers who were 18 years or older and whose loved one had died within the preceding 2 to 12 months.

Materials

All measures administered in Uganda were translated into Luganda, Runyankore-Rukiga, and Swahili, and those administered in Kenya were translated into Kiswahili, using a rigorous forward- and back-translation process (Wild et al. Reference Wild, Grove and Martin2005). Caregivers provided caregiver and patient demographic and medical data. Patient data were also obtained from chart reviews.

The QODD questionnaire (Curtis et al. Reference Curtis, Patrick and Engelberg2002; Patrick et al. Reference Patrick, Engelberg and Curtis2001) was used to measure the quality of dying and death. We utilized the 4 truncated domains identified by Downey et al. (Reference Downey, Curtis and Lafferty2010) in our analyses, rather than the original 6 QODD domains (Patrick et al. Reference Patrick, Engelberg and Curtis2001), to reduce the substantial missing item responses and cultural nonrelevance of some QODD items (Curtis et al. Reference Curtis, Downey and Engelberg2013). These 4 domains, comprising 13 items, include: Symptom Control, reflecting symptom management and autonomy; Preparation, reflecting tangible preparations for dying, such as funeral planning and visits with a religious/spiritual advisor; Connectedness, reflecting closeness with family and friends; and Transcendence, reflecting death acceptance and readiness for death (Downey et al. Reference Downey, Curtis and Lafferty2010). Two additional items assess the overall quality of life in the last 7 days of life and the overall quality of the moment of death. All items are rated on the quality of the patient’s experience from 0 (terrible experience) to 10 (almost perfect experience). To address potential literacy limitations, participants could use a face-rating scale that has been shown to be valid for use in African patient samples (Blum et al. Reference Blum, Selman and Agupio2014). Summed subscale scores were calculated and then standardized to a 0 to 100 scale, with higher scores indicating better quality of dying and death.

Caregivers also completed the FAMCARE scale, a validated, 20-item measure of family satisfaction with care for patients with advanced cancer (Kristjanson Reference Kristjanson1993; Ringdal et al. Reference Ringdal, Jordhøy and Kaasa2003). Satisfaction with aspects of care is rated from 0 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied), and a summed total score is calculated; higher scores indicate greater family satisfaction with care.

Procedure

In Kenya, the Institutional Research and Ethics Committee of the Moi Teaching and Referral Hospital (#FAN: IREC 1700) provided ethics approval for the study to be conducted at the Eldoret and Nyeri Hospices. The Nairobi Hospice Ethics and Standards Committee (no approval number) provided ethics approval for this study to be conducted at the Nairobi Hospice. The study in Uganda received approval from the Hospice Africa Uganda Research and Ethics Committee (#HAUREC-034/17) and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (#SS 4434). Both studies also received ethics approval from the Research Ethics Board of the University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (Kenya study: #15-5080-BE; Uganda study: #18-5055). The Kenyan study was conducted from November 2016 to May 2017; the Ugandan study was conducted from November 2018 to September 2019.

Eligible bereaved caregivers available within the data-collection timeframes were identified by hospice staff or volunteers 2 to 12 months after patient death. They were contacted in person, by telephone, or via text to inform them that research staff would be approaching them about the study. Interested caregivers were then contacted by research staff and given the details of the study. Written informed consent was obtained from those willing to participate; if literacy was insufficient, approval by thumbprint or documented verbal consent was obtained. Questionnaires were administered either by telephone or in an in-person interview that took approximately 45 to 90 minutes to complete. Participants were compensated either US$5 or US$15 for travel costs.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25 software. The alpha level was set at .05. Missing data were treated with listwise deletion. Demographic characteristics of patients and their caregivers and the medical characteristics of patients were summarized using descriptive statistics. Patients and caregivers were compared between the 2 countries on the characteristics using independent-samples t-tests or Pearson’s chi-square tests. Characteristics that differed significantly between countries were included as covariates in multivariable analyses. We examined ranges of overall quality of dying and quality of moment of death ratings for both countries by plotting percentage frequencies for categorized quality ranges of item ratings: ratings from 0.0 to 2.9 reflected terrible to poor quality of dying or death; ratings from 3.0 to 6.9, intermediate quality; and ratings from 7.0 to 10.0, good to almost perfect quality (Curtis et al. Reference Curtis, Patrick and Engelberg2002).

Comparisons between Uganda and Kenya of the QODD subscale scores and the overall quality of dying and quality of moment of death ratings were conducted using univariate ANOVAs. Comparisons between Uganda and Kenya of the categorized quality ranges of scores for the subscales and for the quality of dying and quality of moment of death ratings were conducted using Pearson’s chi-squared tests.

Using multiple linear regressions, the QODD subscale scores were then examined as predictors of quality of dying, quality of moment of death, and family satisfaction with cancer care for each country. These analyses were conducted with and without empirically identified sociodemographic and medical covariates.

Results

Sample characteristics

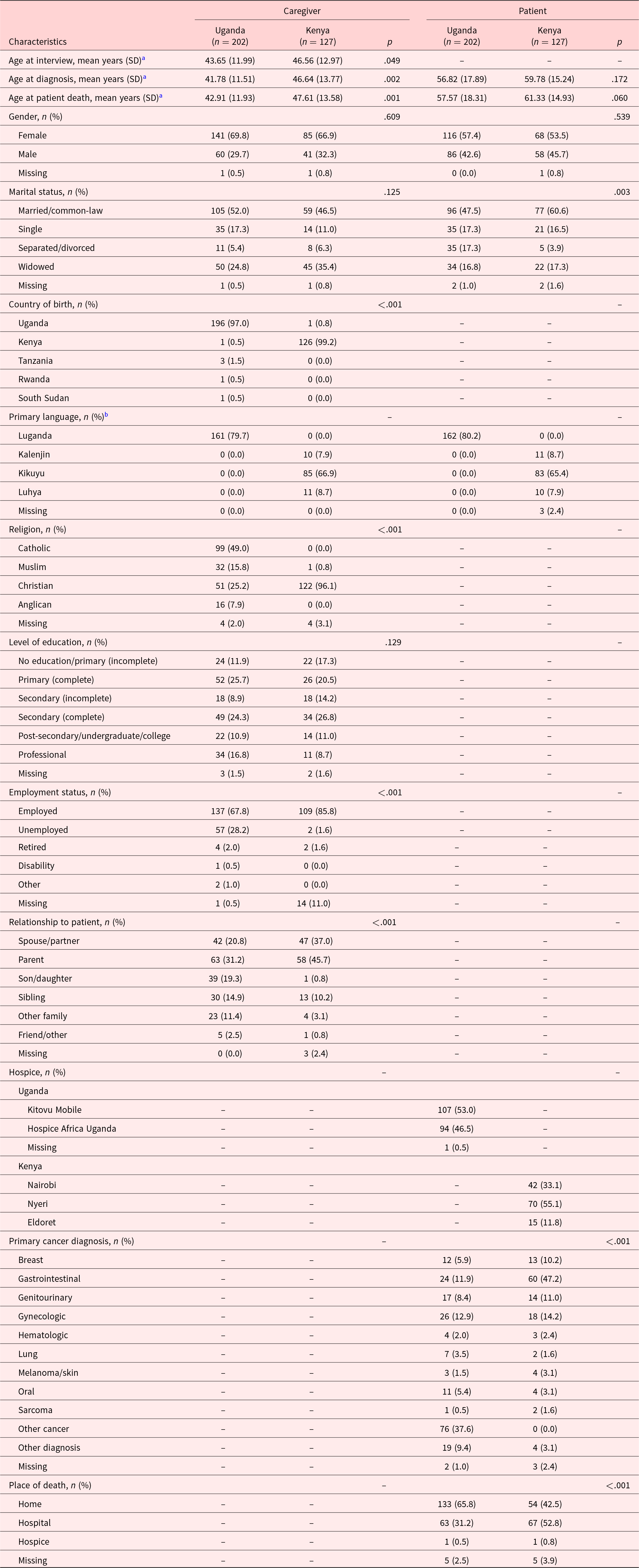

The sample included 202 of 205 (98.5%) approached Ugandan caregivers (2 declined participation; 1 became distressed during interview) and 127 of 129 (98.4%) consenting Kenyan caregivers (Table 1). The majority of Ugandan caregivers were recruited from Kitovu Mobile Hospice (53.0%), and the majority of Kenyan caregivers were recruited from Nyeri Hospice (55.1%). The Ugandan caregivers were significantly younger than the Kenyan caregivers at time of interview (p = .049), at patient diagnosis (p = .002), and at patient death (p = .001). Half of the Ugandan caregivers (49.0%) identified as Catholic, whereas almost all Kenyan caregivers (96.1%) identified as Christian (p < .001). Fewer Ugandan than Kenyan caregivers were employed (Uganda = 67.8%, Kenya = 85.8%. p < .001). The majority of caregivers were parents (Uganda = 31.2%, Kenya = 45.7%) or spouses/partners (Uganda = 20.8%, Kenya = 37.0%, p < .001) of patients.

Table 1. Caregiver and patient demographic and medical characteristics

SD = standard deviation.

a Caregiver age at interview, diagnosis, and patient death: both countries had missing age-related data, which accounts for the older mean caregiver age at patient death than at interview in Kenyan caregivers.

b Primary language: only language categories with frequencies >5% are reported; a statistical comparison of the countries was not conducted with this characteristic due to the numerous languages reported.

No significant age differences were observed in patients between countries (p = .060–.172). Fewer Ugandan than Kenyan patients had been married or in a common-law relationship (Uganda = 47.5%, Kenya = 60.6%), while more Ugandan patients than Kenyan patients had been separated or divorced (Uganda = 17.3%, Kenya = 3.9%, p = .003). In Uganda, the most commonly reported cancer was “other cancer” (37.6%), whereas in Kenya, the most common cancer was gastrointestinal cancer (47.2%). Ugandan patients were more likely to die at home (Uganda = 65.8%, Kenya = 42.5%) and less likely to die in a hospital (Uganda = 31.2%, Kenya = 52.8%, p < .001).

Comparison of QODD overall quality of dying and death and subscale score categorical frequencies

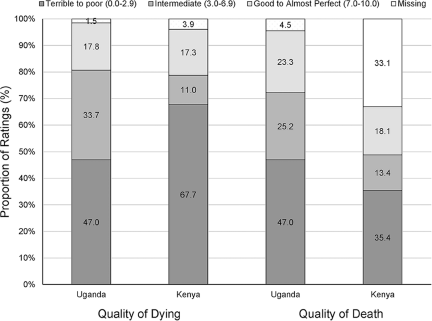

In Figure 1, there were significant differences between the countries in the frequency distributions across quality response categories for both overall quality of dying and overall quality of moment of death (p < .001). Ugandan caregivers rated the overall quality of dying of their deceased loved one less frequently as terrible to poor than did Kenyan caregivers (Uganda = 47.0%, Kenya = 67.7%) and more frequently as intermediate (Uganda = 33.7%, Kenya = 11.0%). Equally small proportions of caregivers from both countries indicated good to almost perfect quality of dying (Uganda = 17.8%, Kenya = 17.3%). Compared to Kenyan caregivers, Ugandan caregivers more frequently rated overall quality of moment of death as terrible to poor (Uganda = 47.0%, Kenya = 35.4%), intermediate (Uganda = 25.2%, Kenya = 13.4%), and good to almost perfect (Uganda = 23.3%, Kenya = 18.1%). Kenyan caregivers showed substantial missing ratings for quality of moment of death (33.1%).

Figure 1. Comparison of percentage frequencies of overall dying and death ratings between Ugandan and Kenyan Caregivers.

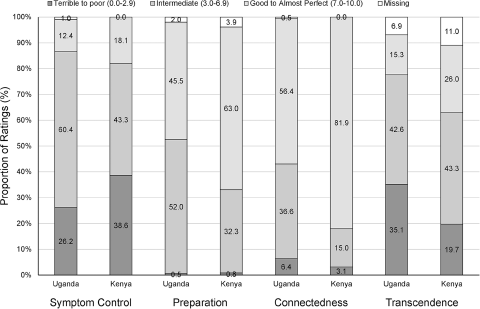

In Figure 2, there were significant differences between Ugandan and Kenyan caregivers in the frequency distributions across quality response categories for all QODD subscales (Symptom Control, p = .007; Preparation, p = .003; Connectedness, p < .001; Transcendence, p = .004). Smaller proportions of Ugandans than Kenyans rated their loved ones’ Symptom Control (Uganda = 26.2%, Kenya = 38.6%) as terrible to poor. Larger proportions of Ugandans than Kenyans rated their loved ones’ Symptom Control (Uganda = 60.4%, Kenya = 43.3%), Preparation (Uganda = 52.0%, Kenya = 32.3%), and Connectedness (Uganda = 36.6%, Kenya = 15.0%) as intermediate. Smaller proportions of Ugandan than Kenyan caregivers reported good to almost perfect Symptom Control (Uganda = 12.4%, Kenya = 18.1%), Preparation (Uganda = 45.5%, Kenya = 63.0%), Connectedness (Uganda = 56.4%, Kenya = 81.9%), and Transcendence (Uganda = 15.3%, Kenya = 26.0%).

Figure 2. Comparison of percentage frequencies of subscale scores between Ugandan and Kenyan Caregivers.

Comparison of Uganda and Kenya on QODD domains scores

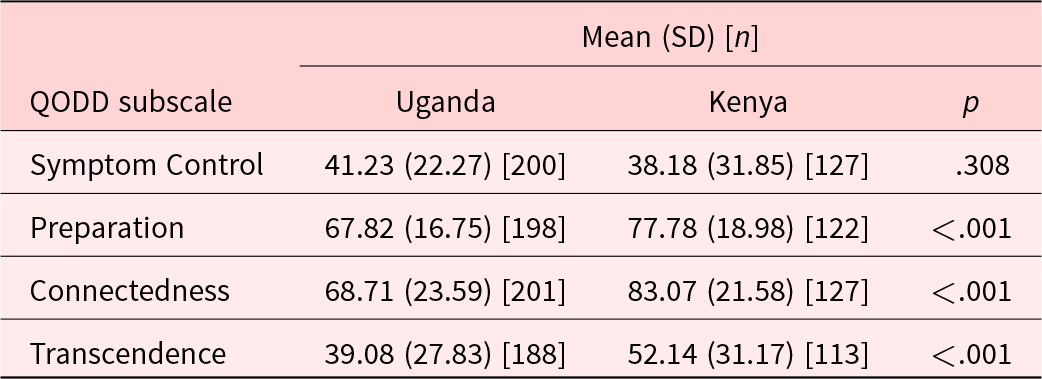

In Table 2, Ugandan caregivers reported significantly lower ratings on Preparation (Mean ± SD: Uganda = 67.82 ± 16.75, Kenya = 77.78 ± 18.98, p < .001), Connectedness (Uganda = 68.71 ± 23.59, Kenya = 83.07 ± 21.58, p < .001), and Transcendence (Uganda = 39.08 ± 27.83, Kenya = 52.14 ± 31.17, p < .001). No significant difference was found between countries on Symptom Control (p = .308).

Table 2. Comparison of QODD subscale scores between Uganda and Kenya

SD = standard deviation.

QODD domains as correlates of overall quality of dying and death and family satisfaction with care

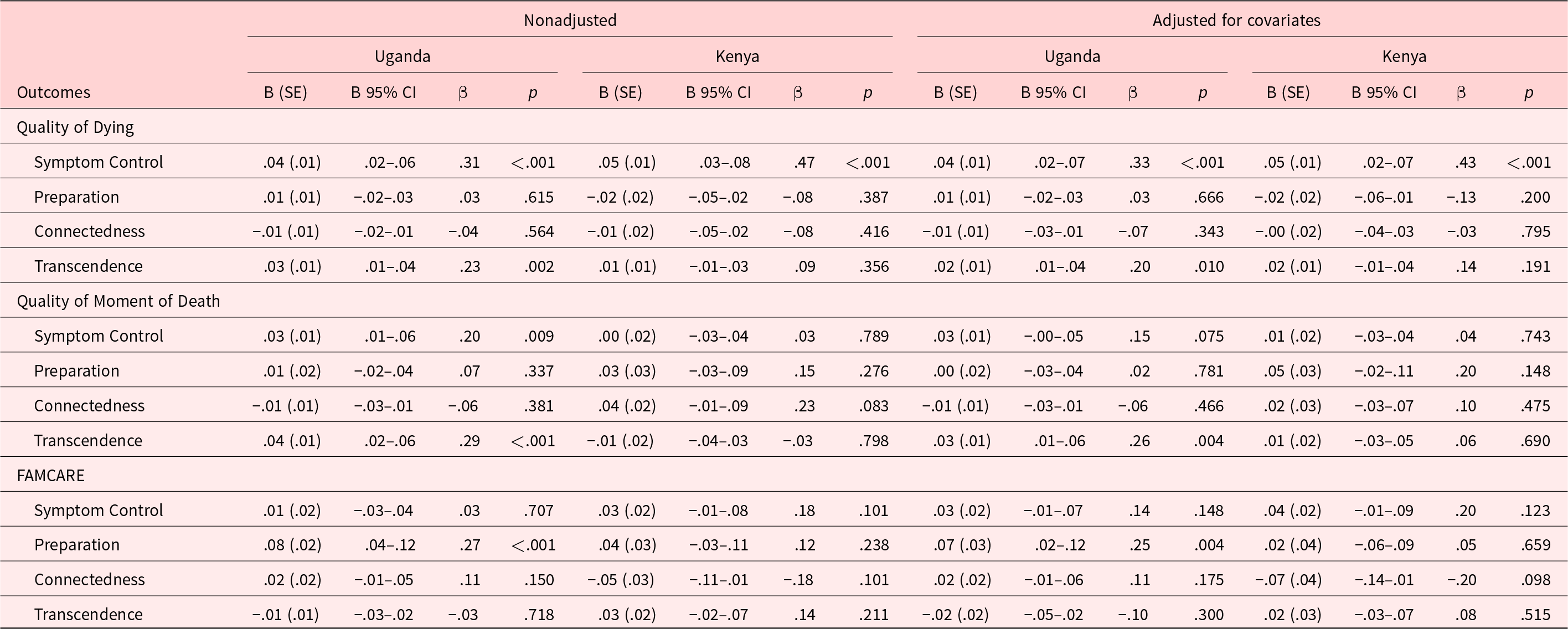

In Table 3, without controlling for covariates, better overall quality of dying in Ugandan patients was associated with better Symptom Control (β = .31, p < .001) and Transcendence (β = .23, p = .002). In Kenyan patients, better overall quality of dying was associated only with better Symptom Control (β = .47, p < .001). These relationships remained when accounting for covariates.

Table 3. QODD subscale scores as correlates of overall quality of dying and death and family satisfaction with Cancer Care in Uganda and Kenya

B = unstandardized coefficient, SE = standard error, β= beta (standardized coefficient), CI = confidence interval.

Covariates for overall quality of dying include caregiver relationship to patient (p = .044) and patient place of death (p = .027). Covariates for overall quality of moment of death include caregiver age at patient death (p = .049) and patient primary diagnosis (p = .001). Covariates for FAMCARE include caregiver age at patient death (p = .023), caregiver marital status (p = .039), caregiver religion (p < .001), caregiver level of education (p = .012), caregiver employment (p = .011), patient primary diagnosis (p = .004), and patient place of death (p = .001).

Better overall quality of moment of death in Ugandan patients was also associated with better Symptom Control (β = .20, p = .009) and Transcendence (β = .29, p < .001), whereas it was not significantly associated with any QODD domain in Kenyan patients. When controlling for covariates, only the association involving Transcendence remained significant in Ugandan patients (β = .26, p = .004).

Better family satisfaction with care given to Ugandan patients was significantly associated with better Preparation, both without (β = .27, p < .001) and with (β = .25, p = .004) covariates.

Discussion

This study of the quality of dying and death of patients who had received hospice care in Uganda and Kenya demonstrated that preparation and connectedness were frequently rated good to almost perfect in both countries, while symptom control and transcendence were frequently rated as intermediate. However, almost half of the patients in hospice care in Uganda and over two-thirds in Kenya reportedly experienced overall terrible quality of dying and death. The preparation, connectedness, and transcendence domains were unexpectedly poorer in Ugandan than Kenyan patients, contrary to the countries’ relative palliative care development rankings based on objective quantification metrics. It is unclear to what extent these differences were due to differences between the 2 countries in the nature of care, cancer types, or caregivers’ demographic characteristics.

The relatively low ratings on symptom control in both countries are consistent with reports of inadequate pain and symptom management in African palliative care settings (Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Powell and Mwangi-Powell2018; Harding et al. Reference Harding, Selman and Agupio2011; Kikule Reference Kikule2003; Namukwaya et al. Reference Namukwaya, Mwaka, Namisango and Silbermann2021; Powell et al. Reference Powell, Ali and Luyirika2017). We found that poor symptom control was significantly related to poor quality of dying, corresponding to the findings of our earlier Ontario study (Mah et al. Reference Mah, Hales and Weerakkody2019a). This finding highlights the urgent need in both countries to improve access to effective pain and symptom management in palliative care. Efforts in both countries to increase opioid availability, such as adopting less restrictive prescribing policies and legalizing prescription privileges for clinical officers and nurses, have met with barriers. These include lack of storage capacity for medications, trained personnel to administer them, supply problems, and sociocultural fears of addiction (Finkelstein et al. Reference Finkelstein, Bhadelia and Goh2022; Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Powell and Mwangi-Powell2018; Kamonyo Reference Kamonyo2018).

The psychosocial domains of preparation for death and interpersonal connectedness notably were rated relatively highly in both countries. These ratings may reflect the importance of religion, spirituality, and communality in African cultures and the close involvement of significant others with individuals who are near the end of life (Agbiji and Swart Reference Agbiji and Swart2015; Etta et al. Reference Etta, Esowe and Asukwo2016; Grant et al. Reference Grant, Brown and Leng2011a; Selman et al. Reference Selman, Brighton and Sinclair2018). Although preparation for death, connectedness to others, and spirituality have also been regarded as important by seriously ill patients and bereaved family members in Western settings (Steinhauser et al. Reference Steinhauser, Christakis and Clipp2000), their relative contributions to a good death and the potential for them to be supported may be shaped by the cultural context. In that regard, we previously reported that Kenyan caregivers rated their loved ones as faring better on interpersonal and spiritual concerns near the end of life than did Canadian caregivers (Mah et al. Reference Mah, Powell and Malfitano2019b). Spirituality and family support may be important resources in the African context that facilitate coping, even when there is poor pain management (Selman et al. Reference Selman, Harding and Agupio2010, Reference Selman, Higginson and Agupio2011).

Based on caregiver reports in the present study, the Kenyan patients showed better preparation for death, connectedness with loved ones, and transcendence than Ugandan patients, contrary to our hypothesis. This could be due to differences in the samples, treatment settings, or resources. It may also be that objective ratings of palliative care development (Connor Reference Connor2020) do not correspond to the subjective experience of dying and death. Challenges in palliative care delivery in Africa include the lack of trained palliative care providers, medication shortages, and limited palliative care funding (Kamonyo Reference Kamonyo2018; Namukwaya et al. Reference Namukwaya, Mwaka, Namisango and Silbermann2021). Community-level comparative studies with patients and their caregivers from both countries are needed to elucidate other sociocultural factors that may underlie these differences.

In the Ugandan subsample, transcendence (i.e., death acceptance) was the most consistent correlate of better quality of dying and death, and preparation for death was a correlate of greater family satisfaction with care. These relationships were not observed with Kenyan patients, possibly due to the smaller size of the Kenyan subsample and correspondingly reduced power in multivariate analyses. We previously reported a similar relationship between acceptance of dying and the overall quality of dying and death in Ontario patients with advanced cancer (Mah et al. Reference Mah, Hales and Weerakkody2019a). However, the relatively low transcendence scores for both Ugandan and Kenyan patients may arise from a lack of prognostic information provided to seriously ill patients in Africa and consequent expectations about being cured (Grant et al. Reference Grant, Brown and Leng2011a, Reference Grant, Downing and Namukwaya2011b; Love et al. Reference Love, Karin and Morogo2020) or the cultural prohibition of conversations about death (Ekore and Lanre-Abass Reference Ekore and Lanre-Abass2016; Love et al. Reference Love, Karin and Morogo2020). Nonetheless, African palliative care practitioners have reported that patients with advanced cancer responded well when end-of-life conversations were initiated prior to palliative care referral (Low et al. Reference Low, Merkel and Menon2018). The relationship between better family satisfaction with care and greater preparation for death in Uganda may reflect the hospice services provided. As preparation for death includes spiritual care and practical matters such as funeral and financial planning, it is possible that the hospices provided holistic support to the patient that both was satisfactory to the family and addressed these preparatory issues. However, the specific care practices at each hospice were not available for analysis.

Limitations

This is the first study to compare the quality of dying and death in Uganda and Kenya using a proxy-reported outcome measure of the patient’s experience. These findings complement the global palliative care rankings based on objective indicators (Connor Reference Connor2020). Limitations of this study should be noted. The proxy ratings of the quality of dying and death were based on the experience of patients who had received hospice care and therefore may not generalize to the experience of individuals who died without such care. The QODD and the FAMCARE were rigorously forward- and back-translated, but these measures have not yet been formally validated for use in African settings, and certain QODD items may not be culturally applicable (Mah et al. Reference Mah, Powell and Malfitano2019b). Although proxy ratings by bereaved caregivers are the most practical method to assess dying individuals’ experiences, there can be memory and recall bias. The caregivers’ emotional state during data collection may also bias their ratings, although previous research suggested that QODD ratings by bereaved caregivers are not affected by degree of bereavement grief (Hales et al. Reference Hales, Chiu and Husain2014).

Our analyses were based on the 4 truncated QODD domains (Downey et al. Reference Downey, Curtis and Lafferty2010) to minimize substantial missing item responses due to their individual or cultural nonrelevance (Curtis et al. Reference Curtis, Downey and Engelberg2013). A more culturally relevant and generalizable measure of the quality of dying and death is urgently needed for research and clinical application in Africa and in other global regions.

Conclusions

This study of the quality of dying and death of patients with advanced cancer in hospice care in Uganda and Kenya revealed both strengths and limitations in this outcome in both countries. A high degree of spiritual preparation and social connectedness was reported for the majority of patients in hospice care in Uganda and Kenya. However, there was poor symptom control and poor overall quality of dying and death in both countries. These findings highlight the urgent need for funding, training, and resources to improve the quality of palliative and end-of-life care in this region. Future research may benefit from a modified QODD to enhance its cultural relevance and validity for use in diverse end-of-life care settings; such research is now underway (An et al. Reference An, Tilly and Mah2022).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the bereaved caregivers in both Uganda and Kenya for their participation in the study. The authors would like to thank Lesley Chalklin, Coordinator, Global Institute of Psychosocial, Palliative and End-of-Life Care (GIPPEC), for coordinating the Uganda quality of dying and death study, Jacqueline Namulondo and Rose Nabatanzi for coordinating caregiver recruitment, and Timothy Muwanguzi and Mackuline Atieno for their work on data collection. They thank the hospice managers and staff for facilitating data collection in Kenya and Zipporah Ali, MD, MPH, and her staff at the Kenyan Hospice and Palliative Care Association for their support. This article presents independent research. The views expressed in this publication by Richard A. Powell are his own and not necessarily those of the NIHCR or the Department of Health and Social Care, London, UK.

Funding

This work was supported by internal funding (no grant number) from the Global Institute of Psychosocial, Palliative and End-of-life Care (GIPPEC: Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, University Health Network; and University of Toronto), Toronto, Ontario, Canada, and, for Richard A. Powell, by support from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration Northwest London.

Competing interests

The authors declare none. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.