On May 25, 2020, George Floyd was killed while being detained by four Minneapolis police officers after being arrested on suspicions of using a counterfeit $20 bill. During the arrest, three of the officers knelt on George Floyd’s legs, back, and neck for nearly 8 minutes despite George Floyd pleading 20 times that he could not breathe (MacFarquhar, Reference MacFarquhar2020; Neuman, Reference Neuman2020). However, the officers repeatedly dismissed his indications of medical distress, and George Floyd was pronounced dead about an hour later. Just over 2 months earlier, Breonna Taylor was fatally shot by police officers as she slept in her home in Louisville, Kentucky. The officers were there to serve a search warrant related to a narcotics investigation, and, according to allegations in a lawsuit filed against the officers, they did not identify themselves as police officers or indicate they were serving a warrant when they entered (Balko, Reference Balko2020). Both Breonna Taylor and George Floyd were unarmed Black citizens.

Protests in response to the two police killings erupted in over 1,700 locations in the United States (Haseman et al., Reference Haseman, Zaiets, Thorson, Procell, Petras and Sullivan2020) and even spread overseas (Rahim & Picheta, Reference Rahim and Picheta2020) as demonstrators across the world gathered to decry racism and police brutality. Though this is not the first time the United States has seen mass demonstrations after a Black person was killed in police custody, the recent protests have reignited a critical conversation about police officers’ use of force and, in particular, their disproportionate use of force with Black people and other people of color. In response, large swaths of protestors, politicians, and the public have called for substantial changes to law enforcement agencies. Some of these efforts have focused on reform that targets reducing the use of lethal force among police officers, such as the 8 Can’t Wait campaign (https://8cantwait.org/), whereas others have instead called for defunding police departments and extensively reimagining or reducing police officers’ roles in communities (Fernandez, Reference Fernandez2020).

We argue that industrial-organizational (I-O) psychologists are uniquely situated to contribute to these ongoing conversations about the ways through which lasting and effective change to law enforcement can be enacted. In particular, I-O psychologists possess diverse expertise, which equips us with a distinctive lens through which we can provide evidence-based recommendations. We thus echo the previous call issued by Ruggs et al. (Reference Ruggs, Hebl, Rabelo, Weaver, Kovacs and Kemp2016) for I-O psychologists to actively contribute to the ongoing efforts to revise our approaches to policing. To help leverage our collective expertise, the goal of this article is to build on previous work (e.g., Hall et al., Reference Hall, Hall and Perry2016; Ruggs et al., Reference Ruggs, Hebl, Rabelo, Weaver, Kovacs and Kemp2016) to examine how our field can contribute to improving police practices through the application of current evidence as well as through future research and practical efforts. We focus on the six domains of recruitment, selection, training, performance management, occupational stress, and culture/cultural change. These topics were chosen because they are central to understanding the factors that contribute to unwanted and dangerous on-the-job behavior among law enforcement officers and thus offer pathways through which change can be realized. It is our hope that this focal article will elicit commentaries that contribute to this pivotal conversation by advancing additional ideas, critiques, and recommendations for the future of law enforcement.

An overview of police violence, race, and the need for reform

Before we turn to our discussion of how I-O psychologists can contribute to reimagining the future of policing, it is important to provide a brief overview of police violence and how it disproportionately affects communities of color. Data that track police violence in the United States demonstrate the pervasiveness of the use of deadly force among law enforcement personnel. However, it is difficult to track the precise number of police killings because evidence suggests that records kept by the FBI systematically underreport homicides tied to law enforcement (Loftin et al., Reference Loftin, Wiersema, McDowall and Dobrin2003). According to Justice Department officials, this is because the database of incidents is compiled by allowing each law enforcement agency to self-report the number of officer-involved shootings, which are then recorded in the FBI’s database with no federal oversight (Lowery, Reference Lowery2014).

In response to the bias in this system, other organizations began independently tracking police shootings and other deaths that occur when people are in police custody. For example, The Washington Post began tracking data in 2015 and has since recorded over 5,000 police shooting deaths, including roughly 1,000 deaths that occurred in the last year (i.e., between March 2020 and March 2021; Washington Post, 2021). Similarly, the organization Mapping Police Violence tracks all police-related killings, not just police shootings, and found that police killed nearly 1,100 people in 2019, which averages to about three people per day (Higgins & Shoen, Reference Higgins and Schoen2020). Furthermore, their data revealed there were only 27 days in 2019 in which there were no police killings.

The pervasive use of deadly force in the US is best revealed when these data are compared with data from other countries. Data from June 2015 to March 2016 found that 1,348 people died in police custody in the US (Banks et al., Reference Banks, Ruddle, Kennedy and Planty2016), whereas 21 people died in Australia (Picheta & Pettersson, Reference Picheta and Petterson2020) and 13 people died in the United Kingdom (Independent Office for Police Conduct, 2019). Strikingly, data collected by The Guardian further revealed that more people in the US died as a result of fatal police shootings in the first 24 days of 2015 than had died in the preceding 24 years in the UK (Lartey, Reference Lartey2015). It is important to acknowledge that the US also arrests a greater number of people than do Australia or the UK. However, even when considering the proportion of people who are killed in police custody out of the total number of people arrested, the US still outpaces other countries, suggesting the higher levels of police violence are not accounted for by the greater number of arrests. Indeed, the proportion of deaths among people arrested in the US is double the proportion in Australia and six times larger than the proportion in the UK (Picheta & Pettersson, Reference Picheta and Petterson2020).

In addition to underscoring the prevalence of police violence, efforts to track police-related killings have also illuminated the inequity in who dies in police interactions. Despite making up 13% of the general population, Black Americans account for 26.5%–42.3% of victims of fatal police shootings and are shot at more than twice the rate of White Americans (Burch, Reference Burch2011; DeGue et al., Reference DeGue, Fowler and Calkins2016; Krieger et al., Reference Krieger, Kiang, Chen and Waterman2015; Schwartz & Jahn, Reference Schwartz and Jahn2020; The Washington Post, 2021). Analyses of shooting victims have further found that Black men have the highest risk of death in police interactions of any demographic group in the US (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Azrael, Cohen, Miller, Thymes, Wang and Hemenway2016; DeGue et al., Reference DeGue, Fowler and Calkins2016; Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Esposito and Lee2018) and that this elevated risk holds true across both rural and urban areas (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Esposito and Lee2018). Black victims are also more likely to be unarmed than White or Hispanic victims (DeGue et al., Reference DeGue, Fowler and Calkins2016; Wertz et al., Reference Wertz, Azrael, Berrigan, Barber, Nelson, Hemenway, Salhi and Miller2020). Indeed, despite the general decline in shootings involving unarmed civilians, data on police shootings from January 2020 to February 2021 indicate that Black Americans remain overrepresented among unarmed victims (i.e., they comprised 34% of unarmed victims; The Washington Post, 2021).

Aside from an increased risk of dying in police custody, reports have similarly found that law enforcement officers are 3.6 times more likely to use other forms of force with Black people than with White people, such as using bodily force or tasers (Goff et al., Reference Goff, Lloyd, Geller, Raphael and Glaser2016). Finally, we note that, although Black Americans are at the highest risk for police brutality, Hispanic Americans (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Azrael, Cohen, Miller, Thymes, Wang and Hemenway2016; Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Esposito and Lee2018) and Native Americans (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Azrael, Cohen, Miller, Thymes, Wang and Hemenway2016) are similarly at an elevated risk of being killed in police interactions.

There are multiple explanations for why law enforcement officers may respond with more force, including more frequently responding with deadly force, when interacting with Black people than with White people. One explanation is that Black individuals are more likely to be appraised as threatening or dangerous because of pervasive stereotypes and racial criminalization. As Ruggs et al. (Reference Ruggs, Hebl, Rabelo, Weaver, Kovacs and Kemp2016) summarize, the existence of stereotypic associations between Black people and crime can affect a variety of decisions related to the use of force and other policing behaviors such as who to stop, search, and arrest. Of particular concern for our purposes, there is also a robust literature that has found racial biases in decisions to shoot a target (Correll et al., Reference Correll, Park, Judd and Wittenbrink2007). Indeed, a meta-analysis examining racial biases in shooting tasks concluded that participants were quicker to shoot armed Black targets than armed White targets, were slower to identify and decide not to shoot unarmed Black targets than unarmed White targets, and had more liberal shooting thresholds (i.e., had a bias to shoot rather than not shoot) for Black targets (Mekawi & Bresin, Reference Mekawi and Bresin2015).

Another explanation at the forefront of conversations about police misconduct is the history of policing and Black communities (see Kelling & Moore, Reference Kelling and Moore1988; Waxman, Reference Waxman2017; Wood & Ring, Reference Wood and Ring2019 for more detailed reviews). The inception of the U.S. police force dates back to the Colonial Era and began as a privately funded system of mostly part-time employees (Kelling & Moore, Reference Kelling and Moore1988; Waxman, Reference Waxman2017). The primary purpose of police officers differed across geographic regions, but a central role for Southern officers was to capture and return enslaved people who sought freedom as well as to quell revolts against slavery (Reichel, Reference Reichel1988). Thus, patrollers were explicitly required to focus their scrutiny on Black Americans (Reichel, Reference Reichel1988).

The system of slave patrols formally ended with the conclusion of the Civil War but quickly took on a new form as police officers were then responsible for enforcing Black Codes and the subsequent Jim Crow laws (Wood & Ring, Reference Wood and Ring2019). This perpetuated a system that existed to police a specific segment of the population, Black Americans, while simultaneously ignoring the crimes levied against this community. The sentiment that Black Americans were a dangerous group to be patrolled, monitored, and incarcerated has since been passed down through newer inceptions of the police force, and these historical origins continue to influence the interactions between law enforcement and Black communities today (Butler, Reference Butler2010).

Research and practice domains relevant to police reform

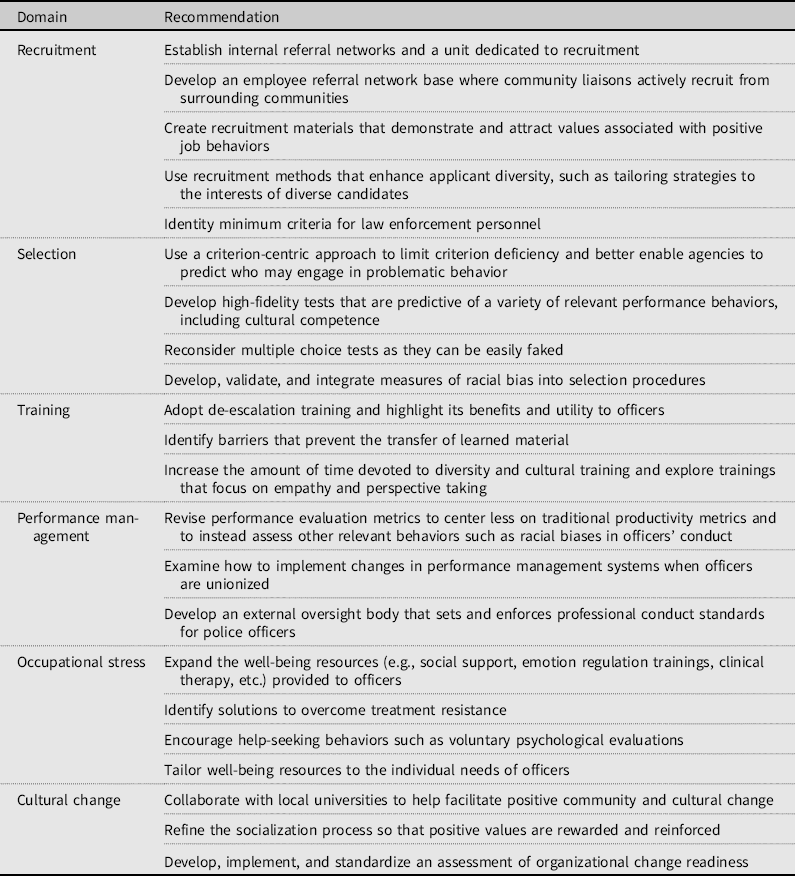

With this context in mind, we now turn our attention to six domains that are relevant to police violence and racism: recruitment, selection, training, performance management, occupational stress, and culture/cultural change. We begin each of the subsections below by reviewing current practices among law enforcement agencies. However, we recognize that law enforcement agencies often adopt differing policies across cities and states, and the information reviewed may not be true of all departments. We then offer evidence-based recommendations for law enforcement agencies while also identifying areas in need of further exploration (summarized in Table 1). We want to acknowledge that we are not suggesting these changes take place in the absence of other structural or systemic changes and argue that both should be considered in tandem. Additionally, these recommendations can be leveraged in efforts to reform police departments but can also inform ways that new systems of community protection can be created in the future (Bell, Reference Bell2021). Finally, we want to note that although we use law enforcement and police interchangeably throughout the manuscript, we are broadly referring to many types of policing (e.g., local police, highway patrol, deputy sheriffs) and believe our recommendations are broadly applicable across different types of law enforcement. We encourage commentaries to expand on our chosen domains and/or supplement, extend, and comment on the research and practical recommendations issued.

Table 1. A Summary of Recommendations for Law Enforcement Agencies

Recruitment

Recent examinations of trends in law enforcement show that the number of full-time employees has been steadily declining (Hyland, Reference Hyland2018), with data suggesting that the police force has reduced by 10.3% across the last two decades (PERF, 2019). This reduction has left administrations and recruiters struggling to fill vacancies in police departments. Despite the federal Office of Community Oriented Policing Services allocating $1 billion in 2009 to help stabilize positions of law enforcement (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Dalton, Scheer and Grammich2010), declines in employment have continued to surge. This has led many agencies to reportedly adopt less stringent hiring standards (PERF, 2019). Although this may ultimately increase applicants, it may also inadvertently reduce the qualifications of current law enforcement personnel. For example, a report from the Fresno Police Department revealed that more than one in four employees believed the department is doing a poor job of attracting and retaining employees of high character, commitment, and competence and nearly a third of employees believed current practices resulted in officers being hired who should have been screened out (Josephson, Reference Josephson2015). This suggests that in attempts to address problems in recruitment, police departments may be hiring individuals who lack the necessary competencies to appropriately perform their jobs.

Analyses of why recruitment has declined in recent years have suggested three reasons: increased military call ups, difficulties recruiting diverse officers, and increased workload. First, military call ups have affected police departments through drawing officers away from the job and increasing recruitment needs (Hickman & Reaves, Reference Hickman and Reaves2006; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Dalton, Scheer and Grammich2010). This is evidenced by a recent report that found that 94% of police agencies had full-time personnel who had exited the job due to being called for military duty (Hickman & Reaves, Reference Hickman and Reaves2006). Furthermore, military service not only poses problems for staffing; it has also been linked to misconduct when officers return to duty (Gonzalez et al., Reference Gonzalez, Bishopp, Jetelina, Paddock, Gabriel and Cannell2019). Prior military service is also generally associated with a variety of aggressive behaviors including domestic violence, physical aggression, and other forms of violence (Elbogen et al., Reference Elbogen, Johnson, Newton, Fuller, Wagner, Workgroup and Beckham2013; MacManus et al., Reference MacManus, Dean, Al Bakir, Iversen, Hull, Fahy and Fear2012; Worthen et al., Reference Worthen, Rathod, Cohen, Sampson, Ursano, Gifford and Ahern2021). Given that veterans are overrepresented among officers (Weichselbaum, Reference Weichselbaum2018), a closer look at this relationship may shed light on the police violence seen across America.

Another important factor that contributes to recruitment deficits is the difficulties law enforcement agencies have in recruiting diverse officers. Indeed, roughly 76% of full-time sworn officers are White, and 86% are male (PERF, 2019). The underrepresentation of officers of color may be due at least in part to differential perceptions of law enforcement across racial/ethnic groups. Compared with White Americans, Black Americans are less likely to trust that police will treat them fairly (Santhanam, Reference Santhanam2020) or believe that police use the right amount of force (Morin & Stepler, Reference Morin and Stepler2016). These sentiments are not limited just to civilians but are also echoed among law enforcement officers. For example, a survey conducted on over 7,000 law enforcement officers revealed that an overwhelming majority of White officers (92%) believed the US has made necessary changes to assure equal rights for Black Americans, but less than a third (29%) of the Black officers agreed (Morin et al., Reference Morin, Parker, Stapler and Mercer2017).

These disparate opinions may contribute to the observed shortages in minority applicants. Indeed, research has found that minority candidates cite racial bias in police departments as the most significant barrier in the recruitment process (Perrott, Reference Perrott1999) and that Black Americans report lower identification with the policing profession than do Whites (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Sacco, McFarland and Kriska2000). Furthermore, because of the disproportionate violence targeting Black communities, individuals from those communities report they do not want to join police agencies because they may be labeled as “traitors” or “sell outs” (Weitzer, Reference Weitzer2000). However, more empirical literature is needed to identify the degree to which the comparatively negative perceptions of police departments among minority communities contribute to the lack of diversity among officers and what can be done to overcome this.

This is important because the difficulty of recruiting diverse officers matters for more than just the number of applicants law enforcement agencies receive. The lack of representation of diverse officers also affects the communities they serve. Previous criticisms of law enforcement agencies have highlighted the discrepancy in the demographic composition between law enforcement and community members in many U.S. cities, arguing this misalignment can contribute to stereotyping and negative community relations (Ruggs et al., Reference Ruggs, Hebl, Rabelo, Weaver, Kovacs and Kemp2016). Furthermore, research has highlighted that communities of color prefer officers that are representative of their community because the residents believe these officers have a better understanding of people of color and will therefore treat individuals in that community better (Weitzer, Reference Weitzer2000).

The final contributing factor to the recent reduction in recruitment success is the increased workload associated with being a police officer. The number of tasks and responsibilities given to police officers, as well as the complexity of the tools used to navigate the job, have rapidly expanded and have influenced how new recruits view the job (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Dalton, Scheer and Grammich2010). Officers are now tasked with solving complex problems in diverse communities, which can prove to be challenging. In addition to traditional tasks such as monitoring neighborhoods, preventing crime, and enforcing traffic laws, police are now often expected to respond to calls of domestic violence, drug overdoses, and mental health issues (Maguire & Mastrofski, Reference Maguire and Mastrofski2000; Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Lovrich and Thurman1999). Moreover, new technological developments such as body cameras, tablets, handheld lasers, and thermal imaging (Strom, Reference Strom2017) have further increased workload and job complexity. This can be challenging as more police officers are performing tasks in which they were not adequately trained nor recruited to handle. Moreover, these additional responsibilities can discourage some potential recruits from pursuing the job while also elevating the standards for qualified candidates. Consequently, the above reviewed issues can restrict the recruitment pool from which departments draw, compromise the quality of officers that are appointed to the job, and further limit departments’ ability to increase the number of parameters on which officers are selected.

Despite the challenges to recruitment, there are steps departments can take to ensure they are recruiting diverse, qualified officers, and we offer several recommendations toward this end. First, a task force on police recruitment and retention recommended that agencies adopt both internal and external recruitment strategies to increase their applicant pools (Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Dalton, Scheer and Grammich2010). Internal strategies include efforts such as building employee referral networks in which highly qualified officers refer new potential hires to the department or establishing a unit dedicated to recruitment. Departments should pair such efforts with external outreach efforts that increase contact and communication between the agency and the community (Hardin, Reference Hardin2016; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Dalton, Scheer and Grammich2010). One way to accomplish this is by appointing community liaisons who work to improve officer–civilian relations, foster an understanding of the needs and perceptions of communities, and, most relevantly, connect with potential applicants in local communities.

We also recommend that police departments carefully consider the values that are emphasized in their recruitment materials and what types of applicants might be most attracted to those messages. For example, a recent content analysis found that police department recruitment messages varied in the degree to which they portrayed themes of community policing and/or militarization (Koslicki, Reference Koslicki2020), and it is possible that applicants may be differentially attracted to each of those themes based on their underlying knowledge, skills, and abilities. Empirical studies have also linked several values and ideologies to officer behavior, such as social dominance orientation, egalitarianism, power, and conformity (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Hall and Perry2016). Working backward from those findings, agencies can design recruitment messages that signal and attract those values that relate to positive behaviors while deemphasizing messages that might signal and attract values that predict unwanted behavior.

Agencies should also be intentional in the recruitment of diverse officers, a practice currently only employed by 20% of agencies (Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Fridell, Faggiani and Kubu2009). Avery and McKay (Reference Avery and McKay2006) offer a summary of best practices for recruiting racial/ethnic minorities and women, including tailoring recruitment strategies and messages to the interests of minority candidates, emphasizing the department’s value for and inclusion of diverse employees, and advertising the successes of diversity management efforts. A recent review on recruitment within law enforcement concluded that concrete, successful strategies for recruiting women and racial/ethnic minority applicants have yet to be identified and encouraged rigorous empirical studies to remedy this deficiency (Donohue, Reference Donohue2021). As a first step in overcoming this crucial gap in our knowledge, I-O psychologists can help by drawing from the general best practices cited above as well as the findings showing that women and minorities have more negative perceptions of law enforcement hiring practices (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Sacco, McFarland and Kriska2000) to advance successful recruitment strategies.

Finally, we contend that agencies would benefit from adopting a federally agreed upon minimum standard for policing. Generating such a standard would help to ensure that departments do not reduce their hiring standards below what is necessary to perform the job in an effort to increase applicant pools. The benefits of doing so would also reverberate to other domains such as selection and training by, for example, identifying minimum performance criteria upon which selection measures can be validated and helping to assess preservice and in-service training needs of cadets and officers. Setting a minimum standard of policing would require extensive job analysis work that might be undertaken by I-O psychologists. During this process, we also encourage I-O psychologists to understand how task requirements might vary across different types of law enforcement (e.g., do the most essential tasks differ across municipal and county police?) and to seek to identify the inimitable functions of policing as compared with other social and community services. Given that a primary impediment to recruitment is the increased complexity in policing responsibilities, this latter recommendation may help to identify ways that law enforcement agencies can rescope the role of officers in ways that are more appealing to potential recruits. This would also come with the added benefit of reducing officer stress and, as early case studies using this approach have demonstrated, improving outcomes among community members (Wood, Reference Wood2020).

Selection

Some degree of selection error is inherent in any selection procedure. However, for jobs that directly affect public health and safety, it is imperative to design selection procedures that leave as little room for error as possible. If the goal is to screen out individuals who are likely to engage in inappropriate or biased job conduct, it is essential to review current tools used in officer selection as well as the criterion on which these tools are validated. This evaluation is somewhat complicated given the variation in practices across law enforcement agencies as well as the use of many proprietary measures that are unavailable for scrutiny. Nonetheless, we focus our review on the most common selection measures used within law enforcement, which include psychological tests, background checks, and education requirements (Hargrave, Reference Hargrave1987; Reaves, Reference Reaves2015; Varela et al., Reference Varela, Scogin and Vipperman1999), as well as the most often used criteria.

Selection measures

Psychological testing has perhaps garnered the most research attention of all law enforcement selection procedures and is among the most common components of selection systems (Cochrane et al., Reference Cochrane, Tett and Vandecreek2003). The most widely used of these tests is the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI; Cochrane et al., Reference Cochrane, Tett and Vandecreek2003; DeCicco, Reference DeCicco2000; Lough & Von Treuer, Reference Lough and Von Treuer2013), which uses a combination of personality and clinical scales to psychologically screen test takers for dispositional traits and potential psychopathologies (Ben-Porath & Tellegen Reference Ben-Porath and Tellegen2008). Yet, despite the popularity of the MMPI among law enforcement agencies, empirical examinations of its criterion-related validity have revealed a complicated pattern of findings. To elaborate, evidence for the predictive validity of the MMPI remains inconclusive (Aamodt, Reference Aamodt2004; Lough & Von Treuer, Reference Lough and Von Treuer2013) and suggests that perhaps only certain subscales of the MMPI predict performance (Aamodt, Reference Aamodt2004). This has led to the creation of numerous indices for scoring the MMPI, such as the “good cop/bad cop” index, which defines a “good cop” profile as someone who scores below 60 on the Hysteria, Hypochondriasis, Psychopathic Deviate, and Hypomania scales and less than 70 on the remaining clinical scales (Blau et al., Reference Blau, Super and Brady1993). Alternative indices propose combining the F (Infrequency), Psychopathic Deviate, and Hypomania scales to assess aggression and impulsivity (i.e., the Husemann Index; Costello & Schneider, Reference Costello and Schneider1996) or to focus more specifically on F and Hypomania because these scales most strongly predict supervisor-rated performance (i.e., the Aamodt index; Aamodt, Reference Aamodt2004). However, although these indices may offer improved validity beyond that of single scale scores, validity evidence for the indices is still mixed, and some studies indicate low or no predictive validity (Aamodt, Reference Aamodt2004; Surrette et al., Reference Surrette, Aamodt and Serafino2004). Of interest, the MMPI has also been found to be unpredictive of sexually and racially offensive conduct (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2021).

Other commonly used tests include the California Psychological Inventory (CPI), which shares items with the MMPI but focuses on general personality rather than psychopathology, and the Inwald Personality Inventory (IPI), which assesses prior behaviors, personality, and psychopathology (Cochrane et al., Reference Cochrane, Tett and Vandecreek2003; Hartman, Reference Hartman1987; Lough & Von Treuer, Reference Lough and Von Treuer2013). As with the MMPI, validity evidence for the CPI and IPI is similarly mixed and differs across subscales (e.g., Aamodt, Reference Aamodt and Weiss2010, advocated for using the tolerance scale from the CPI because it predicted academy performance, job performance, and misconduct). When taken together, these findings demonstrate there is room for considerable improvement in the validity of psychological screening practices and that agencies need to carefully consider the scoring procedures and subscales used for selection decisions.

Agencies should also contemplate the ways in which psychological tests will be used in the selection process. Practitioners in this area differentiate between the method of screening in (i.e., identifying candidates with desired traits) and screening out (i.e., eliminating candidates with undesired traits). In their review of psychological testing among officers, Lough and Von Treuer (Reference Lough and Von Treuer2013) note the advantages of combining both methods and recommend using assessments of psychopathology to screen applicants out while also using measures of positive traits to screen candidates in. However, the authors also acknowledge that screening in is often more difficult, and we recommend that I-O psychologists work to identify psychological tests or subscales that can be used to successfully identify desirable candidates.

Next, background checks are also commonly included in selection batteries and are primarily used to screen applicants out by inferring their character through evaluations of their past behavior. Although there is compelling validity evidence suggesting that background checks can predict future performance when used in an appropriate manner (e.g., Aamodt, Reference Aamodt, Hanvey and Sady2015), they may adversely affect the hiring of minority groups by including biographical and historical information that is tenuously related to the job. For instance, applicants with histories of delinquent or outstanding financial judgments or misdemeanor convictions are less likely to be hired despite the scant predictive validity evidence for these indicators (e.g., White & Kane, Reference White and Kane2013). Selection decisions made based on these factors also tend to exclude minority applicants at a higher rate than nonminority applicants (e.g., Jain et al., Reference Jain, Singh and Agocs2000). Another notable limitation is that current background-check standards allow officers to apply to a new department after leaving their previous one, potentially because they were terminated for misconduct, with no requirement that the new department access the officer’s previous employment record (Williams, Reference Williams2016). This is problematic given that officers who engage in misconduct often receive multiple misconduct complaints across time (Harris & Worden, Reference Harris and Worden2014). It is here where I-O psychologists can best contribute. In addition to identifying the appropriate weights to give particular background information, I-O psychologists can assist with the creation of and advocacy for a national database of employment complaints against officers that is accessible to all agencies in the United States.

A final component included in many selection batteries is an educational requirement. A review done by the Department of Justice found that virtually all law enforcement departments have some minimum educational standard applicants must meet, though the minimum standard tends to be relatively low (Reaves, Reference Reaves2015). To elaborate, 84% of departments require a high school diploma, 15% require the completion of some college, such as holding a 2-year degree, and only 1% of departments require a 4-year degree. Furthermore, more than half of departments allow military service to substitute for educational attainment. These educational standards may be cause for concern given the evidence that greater educational attainment is associated with decreased use of force (Chapman, Reference Chapman2011; Stickle, Reference Stickle2016), higher supervisory ratings of job knowledge and promotions (Truxillo et al., Reference Truxillo, Bennett and Collins1998), and less supportive attitudes toward abuses of police authority (Telep, Reference Telep2008). College education may also be advantageous for police officers because it has been associated with more positive intergroup attitudes and less stereotype endorsement (e.g., Wodtke, Reference Wodtke2012). Therefore, agencies may use this evidence to consider adopting more stringent educational requirements as one way to reduce police misconduct. I-O psychologists can also contribute by conducting additional validation work to assess the predictive validity of specific educational requirements and their potential to produce adverse impact (Decker & Huckabee, Reference Decker and Huckabee2002) to ensure agencies are adhering to legal guidelines.

As a concluding consideration related to selection measures, we also encourage practitioners, researchers, and policy makers to consider the ethicality of law enforcement agencies using proprietary measures that are not accessible for public scrutiny. One of the reasons why it is so difficult to pinpoint and redress the long-standing issues in police departments is because there is a lack of transparency and standardization in police practices and the use of proprietary measures stands in contrast to efforts to remove those impediments. To allow researchers and practitioners to better gauge the ways police misconduct can be reduced through the selection process, agencies may need to consider reducing their reliance on proprietary measures in favor of measures that can be more openly examined by relevant stakeholders (including the public) and can be shared across agencies.

Performance criteria

One critical consideration shared across current and potential future selection measures is the criterion they are intended to assess. The extant literature assessing the validity of the aforementioned selection tools used among law enforcement agencies have relied on a diverse set of performance criteria, ranging from police academy grades (Barbas, Reference Barbas1992) to traffic maintenance and control (Band & Manuele, Reference Band and Manuele1987) to supervisor ratings of communication skills (Landy, Reference Landy1976). Despite this variation, it appears that many of these criteria focus on some form of task performance, which may fail to capture important aspects of police behavior and provide agencies with less opportunity to identify early predictors of problematic behaviors.

To combat this criterion deficiency, I-O psychologists can work in tandem with agencies to apply a criterion-centric approach to validation (Bartram, Reference Bartram2005). This approach begins by first identifying the full set of criteria that are relevant to job performance and then working backward to determine what predictors correspond to those criteria and subsequently what measures best assess the identified predictors. The determination of the relevant criteria should be guided by a thorough job analysis that also adopts a future-oriented approach such that it considers not only what is currently desired on the job but also what new requirements are beneficial for achieving desired changes. This may include cultural competence, de-escalation abilities, use of force records, and indicators of racial bias, among others. Importantly, redefining performance criteria for police officers also requires the revalidation of known selection procedures, which is a process with which I-O psychologists are well equipped to assist.

Moreover, an integral part of accomplishing the preceding recommendation is the identification of valid predictors of racially biased job behaviors, and we acknowledge this will be no easy feat. It is possible that existing selection measures (e.g., integrity tests) can predict whether someone will exhibit racial bias, and researchers and practitioners should carefully evaluate which dimensions and constructs currently captured by selection tests conceptually align with this criterion variable. What these measures may fail to identify, though, is implicit bias, which is notably more difficult to measure but still affects job behaviors. Furthermore, typical approaches to measuring implicit bias (i.e., implicit association tests) have received significant criticism regarding their utility in predicting behavior (e.g., Blanton et al., Reference Blanton, Jaccard, Klick, Mellers, Mitchell and Tetlock2009), calling into question any potential validity for personnel decisions. However, it may be possible to redesign behavior-based selection measures for this purpose. For example, work samples tests and assessment centers could be designed to examine cultural competence by including tasks that require participants to interact with people of various racial/ethnic identities. Tasks such as the previously reviewed shooting simulations that assess the degree of racial bias in correctly identifying targets as threatening or not might also serve as a starting point for developing such selection measures. The advantage of these tasks is that they have the capacity to assess both explicit and implicit biases in applicant responses and performance. Additionally, high-fidelity tasks such as these are strong predictors of job performance (Arthur et al., Reference Arthur, Day, McNelly and Edens2003) and show less adverse impact than do other methods (Dean et al., Reference Dean, Roth and Bobko2008).

A final issue that is critical to consider is applicant faking. Faking is a concern in all selection procedures but the high stakes of correct selection for police officers increases the need to take precautionary measures to identify and reduce faking. Measures that were chosen because they are cost effective and easy to administer, such as multiple-choice entrance exams, may need to be rethought because they are among the easiest types of measures to fake. Personality measures, including the MMPI (Detrick & Chibnall, Reference Detrick and Chibnall2014; Graham et al., Reference Graham, Watts and Timbrook2010), can similarly be faked as applicants can often recognize the items that reflect desirable and undesirable traits. Alternatively, high-fidelity and behavior-based assessments are more robust to faking because it is more difficult to fake skills and abilities that one does not possess. Thus, the previous recommendation for high fidelity testing also provides the benefit of reducing the ease of faking. Other, lower cost solutions are also available, and we direct interested readers to the following: Cao and Drasgow (Reference Cao and Drasgow2019) and MacCann et al. (Reference MacCann, Ziegler, Roberts, Ziegler, MacCann and Roberts2012).

Training

After officers have been recruited and selected, law enforcement agencies can use training to foster a workforce that is prepared to appropriately respond to the demands of the job. Training serves multiple purposes within organizations such as providing the necessary knowledge and skills needed for task performance, communicating the types of behaviors that are valued and rewarded on the job, and orienting newcomers to the culture of the organization (Klein & Weaver, Reference Klein and Weaver2000). Currently, U.S. law enforcement agencies have a relatively brief amount of time in which to accomplish these goals because police academies only last an average of 21 weeks (Reaves, Reference Reaves2016), with some states even reporting that training can be completed in as little as 10 weeks (Kates, Reference Kates2020). This makes police training programs in the US notably shorter than in other countries (e.g., Lord, Reference Lord1998), which may be concerning in light of the findings that only 39% of officers believed training adequately prepared them for the job and only 37% believed training clearly communicated their primary job responsibilities (Morin et al., Reference Morin, Parker, Stapler and Mercer2017).

To better assess the adequacy of current training, it is important to understand the approaches taken to training new officers and the competencies that are emphasized and developed during training. According to a report issued by the Department of Justice (Reaves, Reference Reaves2016), police academies use a mixture of two training methods to develop cadets: a stress-based model and a nonstress model (Reaves, Reference Reaves2016). The stress-based model was developed from military training and places cadets in situations with high levels of physical and psychological demands to accustom trainees to thinking and responding under pressure. This model also often creates an environment that is inflexible to the individual needs and learning styles of trainees wherein cadets are expected to conform to rigid and uniform behavioral standards (Blumberg et al., Reference Blumberg, Schlosser, Papazoglou, Creighton and Kaye2019). The nonstress model, in comparison, involves academic development and physical training and consists of more traditional didactic teaching formats (Blumberg et al., Reference Blumberg, Schlosser, Papazoglou, Creighton and Kaye2019; Reaves, Reference Reaves2016).

Roughly 48% of cadets are trained in environments that mostly rely on the stress model, 18% are trained in academies that primarily draw on the nonstress model, and 34% are exposed to a balanced model (Reaves, Reference Reaves2016). Academies’ reliance on the stress model deviates from the empirical literature, which suggests that cadets are better able to manage challenges in the training and posttraining environment when they are exposed to a balanced model that combines classroom learning with the application of acquired knowledge in simulated contexts (e.g., Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Pitel, Weerasinghe and Papazoglou2016; Blumberg et al., Reference Blumberg, Schlosser, Papazoglou, Creighton and Kaye2019). Reexamining the pedagogical approach to police academy training to incorporate more non-stress-based components may thus offer one opportunity for improved behavioral outcomes. As one additional practical consideration, larger academy class sizes have also been linked to increased future misconduct complaints, suggesting that small classes and more individualized consideration during training may also be advantageous (Gonzalez et al., Reference Gonzalez, Bishopp and Jetelina2016).

Moreover, an examination of specific training content used in police academies revealed that the largest training components were operations; firearms, self-defense, and use of force; self-improvement (e.g., health and fitness, professionalism, ethics); and legal education. Notably, trainees receive an average of only 6 hours of training on stress prevention and management and 5 hours of training on victim response (Reaves, Reference Reaves2016). Furthermore, as stated above, use-of-force training is one of the largest training components in police academies, with an average of 168 hours devoted to content such as weapon retention, verbal command presence, handcuffing, ground fighting, neck restraints, and full body restraints, among others. In contrast, trainees receive comparatively little training on strategies to reduce the need to use force such as mediation and conflict management (trainees receive an average of 9 hours of training) and problem-solving approaches (trainees receive an average of 12 hours of training).

The small number of hours devoted to conflict management and problem solving is closely connected to the recent calls to better train officers in de-escalation strategies. However, despite the growing popularity of de-escalation training in public discourse, there are substantial limitations to our understanding of de-escalation training that make this an ideal area to which I-O psychologists can lend their expertise. Most centrally, there is no clear definition of de-escalation training or the specific goals it attempts to accomplish (Todak & James, Reference Todak and James2018), as well as a paucity of empirical research evaluating its effectiveness (Engel et al., Reference Engel, McManus and Herold2020). Furthermore, the evidence that does exist relies mostly on studies in employment contexts outside of policing (e.g., nursing, psychiatry) and has produced mixed evidence regarding the effectiveness of such training on behavioral outcomes (Engel et al., Reference Engel, McManus and Herold2020).

Therefore, before we can recommend that law enforcement agencies adopt de-escalation training, there is much that still needs to be learned, and we advance some specific research questions I-O psychologists could explore. First, there is a need for empirical examinations of trainee perceptions of and reactions to de-escalation training given the importance these perceptions hold for training outcomes (Sitzmann et al., Reference Sitzmann, Brown, Casper, Ely and Zimmerman2008). Understanding trainee reactions may be particularly important in the case of de-escalation training because its implementation may be seen as reactionary to external pressures (Engel et al., Reference Engel, McManus and Herold2020). Trainees may then come to see this training as something that is being forced on them rather than something that is valued by organizational leadership, potentially leading them to reject the training. Understanding these perceptions and how to foster more positive appraisals among trainees will be critical for successfully implementing de-escalation training.

A second line of research could examine the expected outcomes of de-escalation training and what supports are needed in the transfer environment to improve the application of training on the job. It is currently unclear how effective de-escalation training is in a police context or what components of training are most central to its effectiveness (though a review of potential training components is offered by Oliva et al., Reference Oliva, Morgan and Compton2010), and I-O psychologists can work to develop and identify best practices for this type of training. The most effective de-escalation training might include content that focuses on racial biases in perceptions of threat and how to overcome them to more equally and effectively apply conflict-management tactics across situations. However, testing this proposition requires both practical and empirical work.

Furthermore, although there is ample evidence on the general predictors of whether training will be transferred in the posttraining environment (Blume et al., Reference Blume, Ford, Baldwin and Huang2010), there are specific barriers in need of investigation, such as the possibility that some posttraining environments will fail to support training or even actively discourage the use of de-escalation techniques. This possibility warrants concern given that over a quarter of officers already feel that use-of-force guidelines are too restrictive (Morin et al., Reference Morin, Parker, Stapler and Mercer2017); only about a third of major U.S. cities currently require officers to de-escalate situations before using force (McKesson et al., Reference McKesson, Sinyangwe, Elzie and Packnett2016), and police chiefs and unions have responded negatively to the possibility of implementing de-escalation training (Jackman, Reference Jackman2016). Research examining the way training can be framed to law enforcement agencies and trainees to garner support, such as framing it to emphasize the possible benefits for officers’ safety (Oliva et al., Reference Oliva, Morgan and Compton2010), may help overcome potential barriers to transfer.

A final topic at the forefront of conversations about policing is the need for diversity training. According to the same report issued by the Department of Justice (Reaves, Reference Reaves2016), 95% of police academies offer at least some training on cultural diversity and human relations, but it is typically limited to a handful of hours. Though, perhaps an even larger hurdle to overcome is the known limitations of diversity training. Effective diversity training programs, particularly those that produce long-term behavior change, have remained notoriously elusive (Bezrukova et al., Reference Bezrukova, Spell, Perry and Jehn2016). However, there are some promising developments that may be effective for law enforcement agencies. Primarily, budding evidence suggests that training that encourages perspective taking and/or builds empathy can improve posttraining attitudes (Madera et al., Reference Madera, Neal and Dawson2010) and mitigate self-reported discriminatory behaviors even when measured months after training (Lindsey et al., Reference Lindsey, King, Hebl and Levine2015). This approach aligns with actions some law enforcement agencies are already taking, such as facilitating community events wherein officers can hear first-hand accounts of the ways communities have been affected by police intervention. Community events such as these may also have the added benefit of increasing positive intergroup contact which can similarly mitigate prejudice (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Hall and Perry2016; Pettigrew & Tropp, Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2008). Researchers and practitioners are encouraged to expand on these recommendations to identify the most efficacious diversity training strategies for law enforcement.

Performance management

Performance management systems are another way through which law enforcement agencies can contribute to shaping police officers’ behaviors. Given the many (sometimes competing) purposes that performance management systems serve, building an effective system can be quite difficult for any organization. The complexity of police work only heightens the difficulty of designing a strong system and requires organizations to critically evaluate traditional practices that may not be advantageous in the police context. For example, a commonly desired component of performance management systems is the ability to track performance through objective outcome measures, such as the number of products an employee sells in a given performance period (Cascio & Bernardin, Reference Cascio and Bernardin1981). Although effective for many jobs and organizations, some objective performance measures may backfire when applied to police officers. For example, law enforcement agencies may be wary of setting performance standards based on the number of arrests or traffic tickets one issues or comparing employees on these metrics because such standards can create pressure to intervene even when it is not warranted.

For this reason, numerous concerns have been raised about quota-based approaches and some states have passed legislation to ban law enforcement agencies from setting specific performance standards (Bronstein, Reference Bronstein2015). Yet, a review of performance measurement practices among law enforcement agencies (Sparrow, Reference Sparrow2015) found that performance standards continue to center on crime rates, clearance rates, response times, and, importantly, measures of productivity (e.g., number of arrests, searches, and citations). There are also reports that some law enforcement agencies continue to use quotas or have rebranded quota-based systems as performance goals rather than standards (Bronstein, Reference Bronstein2015), which still rewards and encourages officers to obtain high numbers of arrests or citations.

Overcoming the reliance on traditional productivity metrics will require creative problem solving and is a task well suited to I-O psychologists. I-O psychologists are encouraged to undertake efforts to communicate the need to de-emphasize or eliminate measures of traditional productivity in performance management systems as well as to generate alternative performance metrics that will reinforce the behaviors needed to reduce police misconduct. Examples of such metrics include tracking the successful use of conflict management and de-escalation tactics, rewarding community outreach and training efforts that promote cultural competencies among officers, reinforcing adherence to professional conduct standards, and using citizen satisfaction reports. We also echo the suggestion made by Ruggs et al. (Reference Ruggs, Hebl, Rabelo, Weaver, Kovacs and Kemp2016) to design and implement performance evaluation metrics that assess racial bias in individual officer’s behaviors. However, before any of these performance standards can be implemented, work is still needed to ensure their validity and legal defensibility.

Another related topic that is inextricably linked to the reduction of police misconduct is what actions can and should be taken when officers fail to adhere to standards of performance or professional conduct. Currently, the remediation strategies available to law enforcement agencies are limited by the influential forces of police unions. Police unions can fulfill a variety of functions in law enforcement agencies, but their controversial role in disciplinary processes, in particular, have garnered considerable public scrutiny. Primarily, conversations have centered on the striking number of cases wherein police officers were fired for violating professional conduct only to be reinstated after union intervention (Kelly et al., Reference Kelly, Lowery and Rich2017).

Public criticisms of police unions have also been substantiated by empirical investigations, which have demonstrated that agencies that allow for collective bargaining have higher per capita use of force complaints (Hickman, Reference Hickman2006), complaints were more likely to be dismissed among unionized officers (Hickman, Reference Hickman2006), and complaints of violent misconduct within agencies increased by nearly 40% after collective bargaining was granted (Dharmapala et al., Reference Dharmapala, McAdams and Rappaport2019). Others have noted that unions also create substantial barriers to effective misconduct investigations by negotiating contracts that limit the ways in which investigations are conducted, opposing external oversight agencies, and preventing misconduct records from becoming public (Bies, Reference Bies2017; Walker, Reference Walker2008). Indeed, a review of police union contracts found that 88% included provisions that could limit law enforcement agencies’ ability to take legitimate disciplinary action following officer misconduct (Rushin, Reference Rushin2017).

Given that 73% of municipal police departments were unionized as of 2003 (Hickman, Reference Hickman2006), any efforts for widespread changes to law enforcement will have to also consider the role of, and potential need for reform to, police unions. Practical and empirical efforts should seek to understand how to navigate a unionized environment, how to implement changes to performance management systems when collective bargaining is granted, and how unions may create fault lines or affect the attitudes of police officers. In particular, it is critical to understand and overcome the ways unions may implicitly or explicitly signal that officers will be protected from disciplinary action or dismissal following misconduct, as this undermines the ability of performance management systems to discourage and correct undesirable behavior. One solution may be to establish an external oversight body that sets and enforces professional conduct standards for police officers, such as the licensing boards used for other high-risk professions. This would limit the reach of police unions while also offering a uniform set of policy guidelines for police misconduct and the disciplinary processes that follow from misconduct charges. I-O psychologists can contribute to developing and validating potential licensure requirements and understanding officer and civilian reactions to licensure.

Occupational stress

Law enforcement is consistently ranked as one of the most stressful occupations, and it is important to consider how occupational stress affects police officers and their behavior on the job (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Cooper, Cartwright, Donald, Taylor and Millet2005). In addition to common job stressors faced by other employees, police officers face a variety of unique occupational stressors such as interacting with physical and sexual abuse victims, exposure to recently deceased and decaying corpses, experiencing threats to themselves or their loved ones, and witnessing the death of civilians or colleagues (e.g., Liberman et al., Reference Liberman, Best, Metzler, Fagan, Weiss and Marmar2002; Sheard et al., Reference Sheard, Burnett and St Clair-Thompson2019; Weiss et al., Reference Weiss, Brunet, Best, Metzler, Liberman, Pole and Marmar2010). Consequently, it should come as no surprise that police officers are at high risk for various mental health conditions, including burnout (e.g., Martinussen et al., Reference Martinussen, Richardsen and Burke2007; van Gelderen et al., Reference van Gelderen, Konijn and Bakker2017), depression (e.g., Santa Maria et al., Reference Santa Maria, Wörfel, Wolter, Gusy, Rotter, Stark and Renneberg2018; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Inslicht, Metzler, Henn-Haase, McCaslin, Tong and Marmar2010), and posttraumatic stress disorder (e.g., PTSD; Marmar et al., Reference Marmar, McCaslin, Metzler, Best, Weiss, Fagan, Liberman, Pole, Otte, Yehuda, Mohr, Neylan and Yehuda2006).

Importantly, these mental health conditions can impede decision making and increase the likelihood of unwanted police conduct. For example, research shows that police officers experiencing burnout are more prone to aggressive behaviors (Queirós et al., Reference Queirós, Kaiseler and da Silva2013). Moreover, consistent exposure to stressful circumstances can hinder police officers’ ability to accurately interpret and recall details of life-threatening situations (Lewinski et al., Reference Lewinski, Dysterheft, Priem and Pettitt2016), which could lead to wrongful arrests, an excessive use of force, or inaccurate information being used in investigations of misconduct (Gilmartin, Reference Gilmartin2002; Gutshall et al., Reference Gutshall, Hampton, Sebetan, Stein and Broxtermann2017). Moreover, mental health conditions experienced by officers can also spillover into their nonwork environments. As just one example, PTSD has been linked to both incidences of abusive power in law enforcement (DeVylder et al., Reference DeVylder, Lalane and Fedina2019) and domestic violence among officers (Oehme et al., Reference Oehme, Donnelly and Martin2012).

The high stress that officers experience may also have implications for the observed racial disparities in police violence. Social psychological research on stereotyping and prejudice has long recognized that stereotypes facilitate quick and rapid decision making and offer people a cognitive shortcut to information processing (Fiske & Taylor, Reference Fiske and Taylor1991). Relying on stereotypes in decision making thus allows people to draw quicker but less informed conclusions about situations, such as whether someone poses a threat (Fiske & Taylor, Reference Fiske and Taylor1991; Mears et al., Reference Mears, Craig, Stewart and Warren2017). Though stereotypes can affect decision making under any condition, the use of stereotypes is particularly likely under states of stress, as these states deplete the cognitive resources needed for careful and effortful deliberation (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011). Therefore, in addition to occupational stress being more generally linked to workplace aggression (e.g., Hershcovis, et al., Reference Hershcovis, Turner, Barling, Arnold, Dupre, Inness, LeBlanc and Sivanathan2007), exposure to chronic and acute stress may also increase the likelihood that officers will rely on biased information processing to make important decisions about how and with whom to intervene (Mears et al., Reference Mears, Craig, Stewart and Warren2017).

Successfully coping with and reducing the effects of occupational stress appears to be critical for improving numerous outcomes among police officers, and I-O psychologists can play an important role in mitigating the likelihood of these deleterious consequences by working hand in hand with clinical psychologists and police administration. Presently, there are a vast array of recommendations, resources, and countermeasures available to law enforcement to promote officer well-being. Encouragingly, research shows that resources such as social support (e.g., Prati & Pietrantoni, Reference Prati and Pietrantoni2010), emotion-regulation training (e.g., Berking et al., Reference Berking, Meier and Wupperman2010), mindfulness (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Ciarrochi and Deane2010), and clinical therapy solutions (e.g., behavioral exposure [Tolin & Foa, Reference Tolin and Foa1999]; cognitive restructuring [Peres et al., Reference Peres, Foerster, Santana, Fereira, Nasello, Savoia and Lederman2011]) are effective at improving officers’ well-being. Critically, though, there are considerable barriers that prevent officers from using these resources and instead increase officer reliance on avoidant coping strategies (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Ciarrochi and Deane2010). Thus, I-O psychologists may be most helpful in mitigating the obstacles that prevent the effective implementation of these solutions.

Foremost, I-O psychologists could assist with researching and developing tailored well-being resources. Presently, many departments take a one-size-fits-all mentality when addressing officer well-being, which may not be equally effective when applied to all stressors (Foley & Massey, Reference Foley and Massey2019). Stressors officers face vary on a host of characteristics (e.g., frequency, severity, and novelty), each of which may affect the types of resources officers need. With the rise of occupational health psychology, I-O and occupational health psychologists are well positioned to conduct research illuminating the potential unique linkages between specific stressors and well-being resources. This research can subsequently be leveraged to provide tailored, effective countermeasures within police departments.

I-O psychologists can also contribute by helping to reduce the stigma associated with help-seeking behavior. As highlighted more in the following section, both news and academic outlets have discussed the deeply ingrained stigma against help-seeking behavior in law enforcement (Berg et al., Reference Berg, Hem, Lau and Ekeberg2006; Wester et al., Reference Wester, Arndt, Sedivy and Arndt2010), which may spur police officers to disregard the effectiveness of well-being resources, avoid discussions with coworkers about needing help, and opt out of voluntary psychological evaluations that may reveal underlying or newly developed psychological conditions (Hansson & Markstrom, Reference Hansson and Markström2014; Papazoglou & Tuttle, Reference Papazoglou and Tuttle2018; Royle et al., Reference Royle, Keenan and Farrell2009).

Though there is ample research demonstrating the existence of such stigma, research identifying solutions to overcoming treatment resistance is relatively nascent. We correspondingly encourage I-O psychologists to undertake empirical work to identify the most notable perceived obstacles to seeking treatment among officers, as that is a critical first step toward resolving the most pronounced treatment barriers. Additionally, I-O psychologists can leverage the existing literature concerning gender-based barriers to mental health assistance as a starting point for effectively navigating treatment obstacles among law enforcement (e.g., Vogel et al., Reference Vogel, Wester, Hammer and Downing-Matibag2014; Wester et al., Reference Wester, Arndt, Sedivy and Arndt2010) as the mental health stigma within law enforcement is closely related to its masculine culture. Finally, we note that the overarching culture of law enforcement is a primary contributing factor that reinforces help-seeking stigma, and we turn to the role of culture in the next section.

Culture and cultural change

Police culture is a complex tapestry of norms, customs, and institutions that influence the actions of police officers. Furthermore, police culture has been a point of both academic and public discourse, which has highlighted its historical and racist roots (e.g., Waxman, Reference Waxman2017; Williams & Murphy, Reference Williams and Murphy1990), provided various characterizations (e.g., masculine-driven, Loftus, Reference Loftus2010; “code of silence,” Powers, 1995; mental health stigma, Wester et al., Reference Wester, Arndt, Sedivy and Arndt2010), and called for strong cultural change (e.g., Bazelon, Reference Bazelon2020). Despite this spotlight, police culture remains a crucial point of controversy, as some of its most sustainable factors facilitate some of the most egregious police actions.

Although police culture is by no means a monolith, it is important to highlight the characteristics that harm both police officers and the communities they serve. We have already discussed one of these characteristics, which is pervasive mental health stigma. This belief in a need to be resilient not only harms officer well-being but may also encourage misreporting their current well-being for fear of being perceived as weak by their fellow officers (e.g., Karaffa & Tochkov, Reference Karaffa and Tochkov2013). This mentality is likely exacerbated by the masculine culture of many police departments given that masculinity is associated with greater resistance to expressing vulnerability (Cleary, Reference Cleary2012). The male-dominated culture of law enforcement may also contribute to the rates of aggression and violence observed among officers, and a more gender-diverse police force may help combat unwanted aggression (Bergman et al., Reference Bergman, Walker and Jean2016). Supporting this conclusion, research suggests that women are less likely to engage in aggressive actions and use excessive force than are men (e.g., Porter, & Prenzler, Reference Porter and Prenzler2017) and are more likely to use de-escalation techniques to defuse an otherwise intense situation (e.g., White et al., Reference White, Mora and Orosco2019). Unfortunately, though, the omnipresence of masculinity often puts pressure on women officers to suppress values or traits that counter the dominant culture or to leave the force entirely (e.g., Bikos, Reference Bikos2016; Raganella & White, Reference Raganella and White2004). Fostering an egalitarian climate alongside efforts to increase women’s representation may thus be advantageous, particularly given the evidence that egalitarian climates have been linked to more positive relationships among police departments and communities (Schuck, Reference Schuck2014). Finally, the underrepresentation of women may also contribute to the prevalence of sexual misconduct targeting women officers and civilians (Cottler et al., Reference Cottler, O’Leary, Nickel, Reingle and Isom2014; Maher, Reference Maher2010; Stinson et al., Reference Stinson, Liederbach, Brewer and Mathna2015) given the evidence that sexual misconduct is more likely to occur in male-dominated contexts (Willness et al., Reference Willness, Steel and Lee2007).

An additional deleterious characteristic of police culture is the “code of silence,” or the culture of not reporting and even protecting officers that engage in excessive force or illegal activities (Westmarland, Reference Westmarland2005). In a nationwide sample of officers, ∼ 25% of officers believed that whistleblowing on a fellow officer was not worth it and a staggering 67% believed there would be personal repercussions if they reported such activity (Weisburd et al., Reference Weisburd, Greenspan, Hamilton, Williams and Bryant2000). The report also suggested that turning a blind eye to these activities was fairly common, which is disconcerting given that recognizing misconduct is essential for culture change. The code of silence is likely a product of the “us versus them” mentality that is prevalent among police cultures (Trautman, Reference Trautman2000). Although mutual trust among coworkers is crucial for those operating in high-risk environments, this mentality can be harmful when overextended.

Finally, of particular interest to the focus of our paper is the extent to which law enforcement agencies have positive diversity climates that are welcoming and equitable for officers with diverse backgrounds. It is important to consider diversity climate because it has implications for the treatment of officers of color and can also establish, reinforce, and codify racial biases that affect how officers interact with civilians (Ruggs et al., Reference Ruggs, Hebl, Rabelo, Weaver, Kovacs and Kemp2016). Furthermore, attempts to diversify police forces can backfire in the absence of intentional efforts to foster a more positive environment into which minority officers will enter (Hall, Reference Hall2016). Empirical evidence examining the experiences of Black officers suggests law enforcement agencies do not treat officers of color equitably, finding that the majority report experiencing some form of discrimination on the job (Bolton, Reference Bolton2003; Martin, Reference Martin1994). There have further been a string of recent lawsuits filed against law enforcement agencies that allege discrimination and harassment of Black officers (e.g., Bui & Chason, Reference Bui and Chason2018; Hutchinson, Reference Hutchinson2020; Wood & Nobles, Reference Wood and Nobles2019). However, there is also a notable divide in perceptions of equity in law enforcement agencies among Black and White officers. This is highlighted by a recent survey that found that over half of the Black officers surveyed felt as though White officers were treated better than were minority officers, whereas only 1% of White officers reported feeling the same (Morin et al., Reference Morin, Parker, Stapler and Mercer2017). This suggests a potential perceptual barrier wherein White officers may be unaware of the harmful parts of police culture, and it will be critical to overcome this barrier to spur changes that foster more positive diversity climates.

These aspects of police culture make the task of changing culture daunting. Many of the aforementioned recommendations can contribute to changing police culture; however, the sheer presence of these programs/efforts is not enough to create cultural change. I-O psychologists need to work in tandem with police departments to design an implementation process that creates champions at both high and low levels within the organization as well as advocates in the surrounding community (e.g., Ginsberg & Abrahamson, Reference Ginsberg and Abrahamson1991). Actions to improve police culture should also directly engage leadership because, as Hall et al. (Reference Hall, Hall and Perry2016) note, “the rank-and-file nature of police culture may be advantageous for change if leadership is sincerely committed to diversifying the occupation and shifting its values and practices” (p. 183). A pathway for developing these champions may be through the inclusion of police unions in change efforts. Although police unions currently play a role in reinforcing the status quo, they also have the potential to serve as countercultural entities (Marks, Reference Marks2007).

Additionally, the socialization process of new officers is an area in need of further exploration. Aside from practical appeals (e.g., job security, pay), new recruits often state a primary motivation for joining the police force is protecting and serving the community, whereas the enforcement aspects of the job are often ranked lower (Raganella & White, Reference Raganella and White2004). However, evidence suggests that police attitudes change over time and, specifically, that motivation for providing protection and fair treatment decreases (Oberfield, Reference Oberfield2014). This might be because, as police officers go through the socialization process, their values change to be more aligned with the culture of the department and their actions shift to being more commensurate with what is rewarded. In addition to socialization processes, police culture may also attract and select people who already hold unique values. Examinations of such value differences have found that police cadets and officers tend to score higher on social dominance orientation, conformity, and power compared with the general population, each of which have been linked to a greater acceptance of more severe punishment (Hall et al., Reference Hall, Hall and Perry2016). These findings further underscore the need for future research to extend our understanding of the socialization process of new cadets and identify touch points where more positive values can be reinforced.

Another area where I-O psychologists can contribute is through the development, validation, and implementation of a standardized assessment of organizational change readiness (Rafferty et al., Reference Rafferty, Jimmieson and Armenakis2013). Throughout this manuscript, we have discussed a multitude of recommendations that can propagate positive culture change in law enforcement, but if departments are not ready for change, these may be wasted efforts. For example, there are several illustrative cases where community policing efforts have failed to have the desired effect (e.g., Hafner, Reference Hafner2003). I-O psychologists should work with law enforcement to better understand how ready a department is for culture change and what efforts will lower the barrier for accepting that change. This will also require that I-O psychologists understand the complexity and diversity of police culture across departments, and we recommend that assessments of change readiness consider contextual factors that may vary across departments. For example, officer endorsement of traditional police culture is higher in larger departments and among county rather than municipal police (Silver et al., Reference Silver, Roche, Bilach and Ryon2017). Culture may similarly be affected by departmental funding, local political climates, the presence of special interest groups, and other factors of which I-O psychologists should be aware.

Conclusion

The calls for meaningful change to law enforcement are not new and did not begin with George Floyd or Breonna Taylor. In 1990, Reverend Jesse Jackson declared that the United States was facing a national crisis of racialized police violence after the police shooting death of a Black teenager, and 3 decades later his sentiments are no less true. However, in response to events that continue to unfold during 2020–2021, the calls for long-lasting and substantive change to law enforcement agencies have reached a crescendo. We argue that this presents I-O psychologists with an opportunity to foster positive change during a time when conversations about law enforcement have the attention of the nation. Furthermore, we contend that I-O psychologists are uniquely suited to provide rigorous, evidence-based recommendations for employee and organizational change within law enforcement agencies and that we have a responsibility to do so. Therefore, the goal of the current paper was to summarize the evidence demonstrating a need for substantial changes to or a reimaging of law enforcement and to advance ways in which I-O psychologists can contribute to realizing this goal. We encourage responses to this focal article that build on the recommendations we put forth, identify additional areas to which I-O psychologists could contribute, and provide examples of I-O psychologists effectively facilitating lasting change within police departments. Together, we can leverage the collective insight from our field to foster meaningful change and help to usher in a new, more balanced approach to policing.