Background

Globally, 50,000,000 individuals are currently living with dementia, and 10,000,000 individuals are diagnosed with dementia every year (World Health Organization, 2020). Older adults are more likely than other age groups to be diagnosed with dementia, with a twofold increased risk every 5 years after the age of 65 (Fiest et al., Reference Fiest, Jetté, Roberts, Maxwell, Smith and Black2016). Persons with dementia experience significant symptoms impacting their abilities to complete daily activities, including memory loss, difficulties with decision making, poor language comprehension, and loss of communicative abilities (World Health Organization, 2020).

In Canada alone, more than half a million individuals are living with dementia (Alzheimer Society of Canada, 2021), with more than 260,000 individuals living at home in the community (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2019). More than 90 per cent of Canadians with early dementia, 50 per cent of those with moderate dementia, and 14 per cent of those with advanced dementia live at home in the community rather than in an institution such as a long-term care (LTC) home (Chambers, Bancej, & McDowell, Reference Chambers, Bancej and McDowell2016). Many persons with dementia are staying at home because of the long wait times for LTC, the high costs of LTC, and the preferences of many people with dementia and their families to have the person with dementia remain at home for as long as possible (McCurry et al., Reference McCurry, Logsdon, Mead, Pike, La Fazia and Stevens2017).

With the progressive decline in social, cognitive, and physical abilities associated with dementia, many older adults with dementia living at home increasingly depend on family and friend caregivers (hereafter referred to as caregivers) for support and care. The common definition of a caregiver is a person 18 years or older who provides support or care for an individual with a chronic health condition, physical or cognitive limitation, and/or age-related issues (Turcotte, Reference Turcotte2013). Caregivers are highly involved in the care of older adults with dementia; however, caregivers often report unmet needs for caregiver education and community support (Black et al., Reference Black, Johnston, Rabins, Morrison, Lyketsos and Samus2013). As a result, caregivers experience poor outcomes such as stress, depression, a decline in physical and mental health, and a lack of confidence in caring for older adults with dementia (Brodaty & Donkin, Reference Brodaty and Donkin2009).

There is a need to support caregivers of community-dwelling persons with dementia through psychosocial interventions (e.g., sensory activities, cognitive stimulation, physical activities, art therapy). These have been found to reduce caregiver burden and depression while improving caregiver well-being, quality of life, knowledge about dementia, resilience, and skills for care delivery (DiZazzo-Miller, Winston, Winkler, & Donovan, Reference DiZazzo-Miller, Winston, Winkler and Donovan2017; Jensen, Agbata, Canavan, & McCarthy, Reference Jensen, Agbata, Canavan and McCarthy2015; McCurry et al., Reference McCurry, Logsdon, Mead, Pike, La Fazia and Stevens2017; Vedel et al., Reference Vedel, Sheets, McAiney, Clare, Brodaty and Mann2020). A psychosocial intervention is defined as an intervention that has the aim of reducing or preventing a decline in mental and physical health of caregivers and/or care recipients by targeting activities, skills, competence, and/or relationships to that population (Van’t Leven et al., Reference Van’t Leven, Prick, Groenewoud, Roelofs, de Lange and Pot2013).

There are currently few psychosocial interventions intended for use by caregivers in the community to support persons with moderate to advanced dementia (Clarkson et al., Reference Clarkson, Hughes, Roe, Giebel, Jolley and Poland2018). Many psychosocial interventions are designed for caregivers of persons with early to moderate dementia (Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Agbata, Canavan and McCarthy2015). Other interventions are created for caregivers supporting persons with dementia with little consideration given to differences between stages of dementia and the abilities of persons with dementia (Clarkson et al., Reference Clarkson, Hughes, Roe, Giebel, Jolley and Poland2018). This limits the relevance and usefulness of caregiver interventions, as the needs of persons with dementia vary from stage to stage.

Namaste Care is a psychosocial, multisensory program originally created for use in LTC in the United States to improve the quality of life of persons with advanced dementia and their families and friends (Simard, Reference Simard2013). Its principles consist of providing a comfortable environment, and interacting with persons with dementia through an unhurried, loving touch approach (Simard, Reference Simard2013). Different modalities are combined within the Namaste Care program including music, massage, socialization, aromatherapy, and snacks. Through this approach, family members and health care providers are equipped with practical skills to meaningfully engage people with dementia.

Namaste Care sessions are typically delivered daily by care providers in a quiet room with soft lighting and no interruptions (Simard, Reference Simard2013). In LTC settings, sessions generally last 2 hours and are offered in the morning and afternoon. Family members can join sessions if they wish. Inside the Namaste Care room, relaxing music is played, and scents such as lavender or seasonal scents are diffused. Activities are provided one at a time by care providers. Touch is used through approaches such as hand/foot massages, applying lotions, and hair brushing. A Namaste Care box or cart is used to store items. The included items are based on the individual’s preferences such as lotions, life-like dolls, plush animals, photos, and sensory balls. Throughout the sessions, persons with dementia are monitored by health care providers for signs of pain and discomfort (Simard, Reference Simard2013).

Namaste Care has been implemented worldwide and within various settings including LTC, hospice, acute care, and home settings (Simard, Reference Simard2013). The program has led to favorable outcomes such as reduced use of anti-anxiety and psychotropic medications, lower risk of delirium, decreased pain symptoms, and improvement in quality of life for persons with dementia and in relationships with staff (Bunn et al., Reference Bunn, Lynch, Goodman, Sharpe, Walshe and Preston2018; Karacsony & Abela, Reference Karacsony and Abela2021; McNiel & Westphal, Reference McNiel and Westphal2018; Nicholls, Chang, Johnson, & Edenborough, Reference Nicholls, Chang, Johnson and Edenborough2013; Simard & Volicer, Reference Simard and Volicer2010; Stacpoole, Thompsell, Hockley, Simard, & Volicer, Reference Stacpoole, Thompsell, Hockley, Simard and Volicer2013). Family members are more relaxed during interactions with persons with dementia following Namaste Care (Simard & Volicer, Reference Simard and Volicer2010). To date, only one study explored Namaste Care delivery in a home setting, and it was delivered by volunteers from a hospice organization (Dalkin, Lhussier, Kendall, Atkinson, & Tolman, Reference Dalkin, Lhussier, Kendall, Atkinson and Tolman2020). Dalkin et al. (Reference Dalkin, Lhussier, Kendall, Atkinson and Tolman2020) found that Namaste Care led to increased socialization for persons with dementia. Caregivers, however, had little participation in the intervention, as the focus was on volunteers (Dalkin et al., Reference Dalkin, Lhussier, Kendall, Atkinson and Tolman2020).

Most studies have not involved caregivers in the development or adaptation of caregiver interventions for persons with dementia, thus limiting the practicality and usefulness of interventions (Burgio et al., Reference Burgio, Collins, Schmid, Wharton, McCallum and DeCoster2009; Huang et al., Reference Huang, Kuo, Chen, Liang, Huang and Chiu2013; Liddle et al., Reference Liddle, Smith-Conway, Baker, Angwin, Gallois and Copland2012; Llanque et al., Reference Llanque, Enriquez, Cheng, Doty, Brotto and Kelly2015). Partnering with persons with dementia and caregivers ensures that they can make and influence decisions that impact their lives, such as decisions related to program planning, intervention design, or policies (Health Quality Ontario, 2017). Older adults with advanced dementia may not be able to participate in designing interventions; however, family members have valuable insights that should be shared when collaborating with researchers to develop and refine programs (Treadaway, Taylor, & Fennell, Reference Treadaway, Taylor and Fennell2018). There is a need to involve caregivers in developing interventions for home use to support people with moderate to advanced dementia so that interventions are tailored to their needs and abilities and reflect the voices of care recipients. When adapting programs, contextual modifications may be made to deliver an intervention in a new setting and to have a different type of person deliver the intervention (Stirman, Miller, Toder, & Calloway, Reference Stirman, Miller, Toder and Calloway2013). Programs that were developed for use in LTC settings, such as Namaste Care, would require further adaptation with the collaboration of caregivers prior to being implemented in individual residences.

Prior to implementing the program in home settings, Namaste Care (Simard, Reference Simard2013) would have to be adapted, while ensuring that modifications maintained fidelity. The purpose of this study is to describe and explain suggested adaptations for the Namaste Care program and training procedures in collaboration with caregivers so that it is feasible for the approach to be delivered in a home setting. The research question is: How do caregivers envision the adaptation of Namaste Care for use by caregivers of community-dwelling older adults with moderate to advanced dementia?

Methods

Study Design

The research design for the present study consists of qualitative description (Sandelowski, Reference Sandelowski2000, Reference Sandelowski2010). Qualitative description allows for direct descriptions of phenomena with some room for interpretation of data (Sandelowski, Reference Sandelowski2000, Reference Sandelowski2010). Incorporating direct suggestions of caregivers in revising Namaste Care can help ensure that the program will meet the needs and expectations of caregivers. The present study is one component of a larger study that uses a multi-phase mixed methods design combining both sequential and concurrent qualitative and quantitative strands over time to address a program objective (Creswell & Plano Clark, Reference Creswell and Plano Clark2018). As a follow-up to the present study, caregivers will receive training to deliver the adapted version of Namaste Care at home for persons with moderate to advanced dementia over 3 months, and its feasibility, acceptability, and specific outcomes for caregivers will be evaluated. The protocol for the mixed methods study is published elsewhere (Yous, Ploeg, Kaasalainen, & McAiney, Reference Yous, Ploeg, Kaasalainen and McAiney2020).

Core Components of Namaste Care

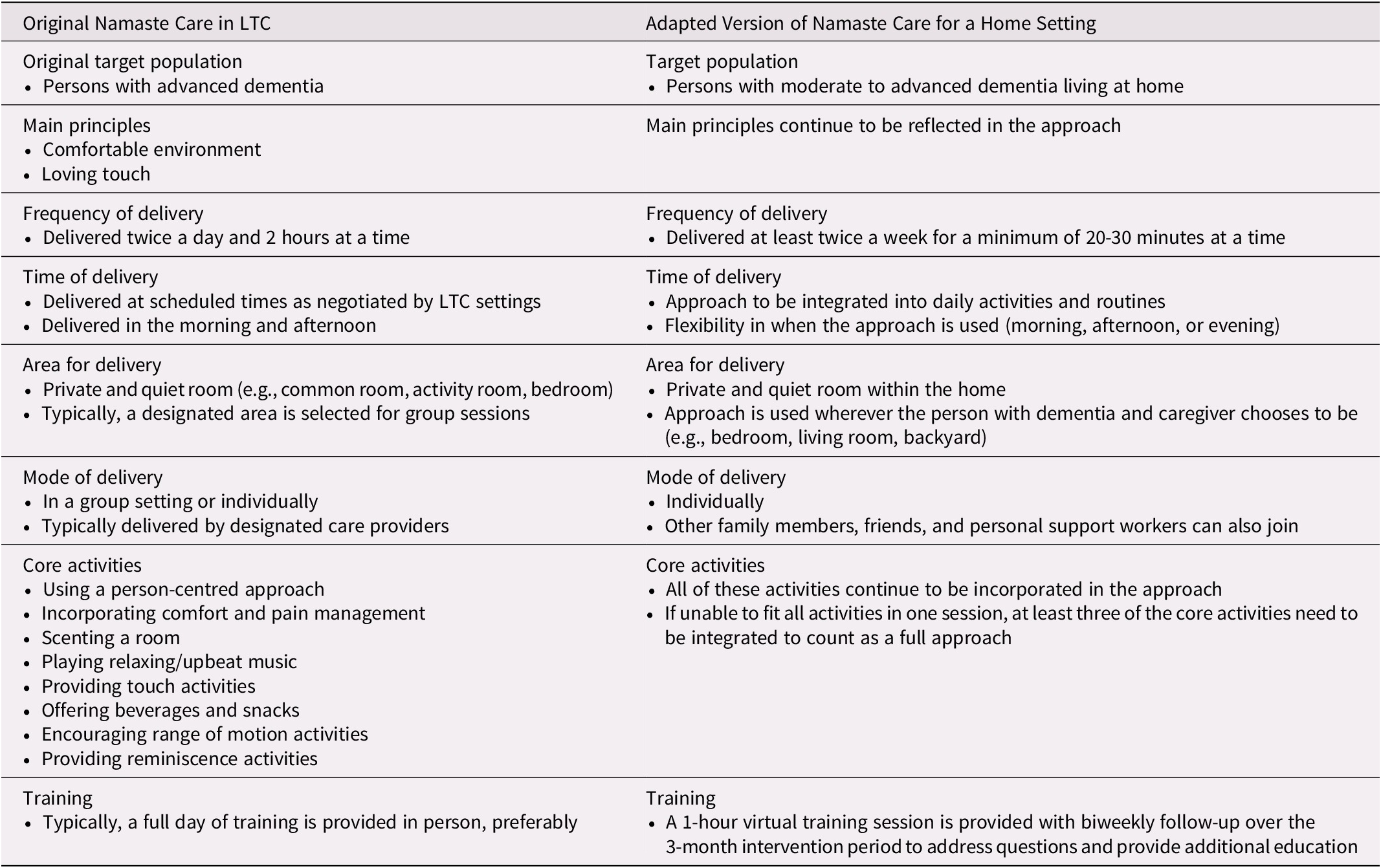

The full structured Namaste Care program (Simard, Reference Simard2013) is expected to be delivered twice a day, 2 hours at a time in the morning and afternoon in a designated LTC room with the following core components: (1) using a person-centred approach, (2) incorporating comfort and pain management, (3) scenting a room, (4) playing relaxing/upbeat music, (5) providing touch activities, (6) offering beverages and snacks, (7) encouraging range of motion activities, and (8) providing reminiscence activities (e.g., photo albums, conversations about life stories) (Kendall, Reference Kendall2019). With the original program, Namaste Care providers are often providing the program as a group therapeutic session for persons with dementia in LTC. A proposed alternative to the full structured Namaste Care program is an adapted Namaste Care program for caregivers at home. The adapted program will retain the original program’s core components and principles (Simard, Reference Simard2013), but provides flexibility for when it is used, how long it is delivered, and what key activities are being offered as seen in a study by Dalkin et al. (Reference Dalkin, Lhussier, Kendall, Atkinson and Tolman2020).

In this present study, it is proposed that caregivers use the adapted Namaste Care program rather than the full structured program designed for use in LTC. Rather than trying to reserve a dedicated time and place for delivering Namaste Care, caregivers are encouraged to creatively integrate the program into their day. The decision was made to use the adapted program rather than the full program, as caregivers in the home setting may not have the time and energy to deliver the program daily, 2 hours at a time, as it is intended in LTC settings. Instead, it is likely that caregivers would find ways to incorporate the adapted Namaste Care program in routine care activities, such as when assisting with personal grooming and providing snacks and beverages in between mealtimes. The main principles of the adapted program that will continue to be upheld are creating a comfortable environment and providing an unhurried, loving touch approach (Simard, Reference Simard2013).

Framework for Namaste Care Adaptation

The System for Classifying Modifications to Evidence-Based Programs or Interventions (Stirman et al., Reference Stirman, Miller, Toder and Calloway2013) was used to guide the adaptation process of Namaste Care (Simard, Reference Simard2013). The framework was used to document modifications for the original Namaste Care program and as a coding framework. Stirman’s et al. (Reference Stirman, Miller, Toder and Calloway2013) framework was created to provide a coding scheme to be able to categorize modifications to pre-existing evidence-based interventions when they are implemented in different contexts or with populations that differ from the ones that were originally targeted. The framework also considers modifications to the processes for training individuals responsible for delivering the intervention. These training modifications are separate from content and context modifications, as training procedures do not typically impact the content of an intervention or the context in which it will be delivered (Stirman et al., Reference Stirman, Miller, Toder and Calloway2013).

In the present study, modifications to training are considered as an implementation strategy that has the potential to increase the successful delivery of the intervention. The framework has been used in previous studies to provide a coding framework for modifications to an evidence-based psychotherapy program (Stirman et al., Reference Stirman, Gutner, Crits-Christoph, Edmunds, Evans and Beidas2015) and pediatric weight management program (Simione et al., Reference Simione, Frost, Cournoyer, Mini, Cassidy and Craddock2020). It has also been used to inform the development of a questionnaire to assess adaptations to evidence-based practices by community health care providers offering children’s mental health services (Lau et al., Reference Lau, Barnett, Stadnick, Saifan, Regan and Wiltsey Stirman2017). The use of a classification system helps to address the tension between fidelity and modifications that is related to maintaining fidelity of interventions without compromising effectiveness through modifications (Scheirer & Dearing, Reference Scheirer and Dearing2011).

The System for Classifying Modifications to Evidence-Based Programs or Interventions framework (Stirman et al., Reference Stirman, Miller, Toder and Calloway2013) is composed of five categories: (1) By whom are modifications made? (2) What is modified? (3) At what level of delivery (for whom/what) are modifications made? (4) To which of the following are context modifications made? and (5) What is the nature of the content modification? The framework was used in the present study to ensure that modifications to Namaste Care do not result in a dramatic departure from the original program while keeping intact the core elements.

Setting

The setting for the study consisted of urban areas in Ontario, Canada. Dr. Yous met with caregivers individually prior to the workshop sessions to support them in preparing for the sessions using a method (i.e., by phone or Zoom) of their choice that adhered to Public Health COVID-19 restrictions at the time of the study.

Sample

Participants consisted of six family caregivers of older adults with moderate to severe dementia. Four small group workshops were held with two to four caregivers present at each workshop. Each caregiver attended two workshop sessions and met with the same group of caregivers each time. Purposive sampling was used including criterion and snowball sampling (Patton, Reference Patton1990). The study inclusion criteria were: (1) being 18 years of age or older with experience providing physical, emotional, and/or psychological support for a family member or friend 65 years of age or older with moderate to advanced dementia within the last 5 years, at home for at least 4 hours a week; (2) being able to speak, write, and understand English; (3) currently living in Ontario, and (4) able to provide informed consent. Caregivers who were no longer caring for a family member or friend at home (i.e., care recipient is living in a LTC setting or died) were also eligible to participate in the study. One participant in the study was a former caregiver who had been last caring for a family member 2 years ago. Persons who were no longer caring for someone at home were invited to participate in the study because they could reflect on their recent home care experiences to inform the adaptation of Namaste Care, and may still identify strongly with the caregiver role (Corey & McCurry, Reference Corey and McCurry2018). Former caregivers often seek to fulfill this role by helping other caregivers of people with dementia through sharing their experiences and lessons learned (Kim, Reference Kim2009; Larkin, Reference Larkin2009). They may also have more time and may be interested in participating in activities such as research. Snowball sampling was used by asking caregivers to share the contact information of the researcher with other caregivers who might be interested in participating in the study.

Recruitment

Caregivers were recruited from the Alzheimer Society of Canada, local Alzheimer Societies, and Dementia Advocacy Canada through social media, online advertising, and newsletters. Dr. Yous discussed the study at virtual dementia education courses and offered staff and client presentations at the Alzheimer Society. Alzheimer Society community program educators and counsellors were asked to refer potential participants to the study by providing them with a study flyer.

Namaste Care Adaptation Workshops

Each caregiver participated in a total of two workshops: an initial and a follow-up session. A total of four workshop sessions with caregivers of community-dwelling older adults with moderate to advanced dementia were held. The workshop sessions occurred over a period of 60–90 minutes. All of the caregivers participated by videoconference except for one caregiver who participated by phone. The purpose of the initial workshop was to present the Namaste Care program to caregivers, provide an opportunity to discuss the program, and learn about the caregivers’ insights regarding adaptations needed for the program so that it could be used at home. The purpose of the second workshop was to present the draft training manual (developed based on results of the first workshop sessions with caregivers) to caregivers, obtain their feedback in the manual and training procedures, and further refine the Namaste Care program. During the first workshop session, Dr. Yous provided caregivers with a 20-minute educational presentation of Namaste Care. As most of the caregivers were actively caring for a family member at home, they were interested in learning about Namaste Care so that they could apply new knowledge to support them in caring for persons with dementia at home. The content presented included: (1) the history of the creation of Namaste Care, (2) how it has been used in LTC, (3) the main principles and components of the program, (4) the benefits of the program supported by research evidence, (5) recommended steps in using the program, and (6) examples of items that can be found in a Namaste Care toolbox. Following the presentation of Namaste Care, Dr. Yous facilitated interactive workshop discussions on caregivers’ suggestions for adaptation of Namaste Care for home use. After the first workshop, the research team developed a draft version of the Namaste Care training guide based on what was shared at the first workshop sessions. This guide was shared by e-mail with participants for their review before the second workshop session.

At the second workshop, caregivers were provided with another 20-minute educational presentation on Namaste Care. The educational content presented at the second workshop included: (1) examples of Namaste Care sessions; (2) key considerations and strategies for delivering and selecting Namaste Care activities (e.g., music, aromatherapy, massages, snacks and beverages, range of motion/exercises, reminiscence activities); (3) how to perform observational assessments of mood, alertness, and pain for persons with dementia before, during, and after Namaste Care; (4) examples of responses of persons with dementia to activities; and (5) strategies to optimize the delivery of Namaste Care. A discussion to seek feedback and further adaptations required for Namaste Care and training procedures including the training guide was facilitated following the educational presentation.

Data Collection

Data collection occurred from October 2020 to January 2021. Demographic data were collected including age, sex, education level, relationship to the person with dementia, length of time as a caregiver, and type of support provided. Workshop discussion guides were developed based on a review of the literature, expert recommendations, and the Stirman et al. (Reference Stirman, Miller, Toder and Calloway2013) framework. See Table 1 for a sample of workshop discussion questions. Notes were taken following the workshop sessions. Workshop discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed by an experienced transcriptionist. In terms of the adaptation process, the experiences and recommendations shared during the workshop sessions were used to inform the adaptation of Namaste Care and the training procedures.

Table 1. Sample of workshop discussion questions

Note. See the protocol paper for the full workshop discussion guide (Yous et al. Reference Yous, Ploeg, Kaasalainen and McAiney2020).

Data Analysis

Qualitative data obtained from the workshop sessions and researcher notes of the sessions were analyzed using thematic analysis, a method that is used to identify themes and patterns within data (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Specifically, experiential thematic analysis was used, as it is suitable for the current study which focuses on participants’ experiences and how they view their world (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2013). Analysis was both inductive and deductive in nature. Inductive coding was used to reveal unique codes that arose from the workshop discussions with caregivers and deductive coding was conducted by using the Stirman et al. (Reference Stirman, Miller, Toder and Calloway2013) framework as an a priori template for codes (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Reference Fereday and Muir-Cochrane2006). The six phases of thematic analysis as described by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) were followed: (1) gaining familiarity with the data, (2) conducting coding, (3) locating themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) developing a definition for themes and naming them, and (6) developing a report.

Dr. Yous reviewed the transcripts twice before beginning to code to gain familiarity with the data, and made reflexive notes about initial thoughts (Damayanthi, Reference Damayanthi2019). Initial reactions to the data were documented. During the process of coding, the research team analyzed data concurrently as interviews were being completed. Data-driven inductive themes were found to complement coding framework themes and shed light on the rationale for why Namaste Care adaptation is needed. Dr. Yous sought feedback from co-authors to ensure that the coding process was sound. Consistent with qualitative description (Sandelowski, Reference Sandelowski2000), constant comparative analysis was used to identify similarities and differences across participants and participant groups. Themes were developed from the codes to highlight meaningful patterns within the data while reflecting the research question. Themes were developed based on similarities between codes and the data (Braun & Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). NVivo version 12 software was used for data management.

Rigour and Trustworthiness

In terms of maintaining rigour and trustworthiness in qualitative research, a reflective journal was kept by Dr. Yous to document personal reactions and past experiences that could impact the study process (Finlay, Reference Finlay2002). Lincoln and Guba’s (Reference Lincoln and Guba1985) trustworthiness criteria were applied throughout the study (i.e., credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability). Credibility was upheld through investigator triangulation by seeking feedback from co-authors, as they hold expertise in research areas including caregivers, people with dementia, community support programs, and/or Namaste Care. This process not only ensured credibility and complementarity, but helped to validate data (Lincoln & Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985). To increase the transferability of the study findings, rich thick descriptions were used to describe the study’s setting and sample (Lincoln & Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985). The research team ensured that the proposed project followed clear logic by conducting a comprehensive review of the current literature to highlight the gaps in existing research.

Ethical Considerations

Ethics approval was granted from the local research ethics board (#10526). All caregivers received a written introduction to the study and an informed consent form written in lay language. To protect the anonymity of the responses of participants in the data set, study IDs were provided for each participant. All information collected in this study was confidential. Caregivers were invited to share only their first names during the workshops. Transcripts were shared between Dr. Yous and the transcriptionist over a password-protected encrypted folder. Participation in the study was voluntary. Caregivers were asked to only share what they felt comfortable disclosing, and none of them experienced emotional distress during the study. The three core principles, respect for persons, concerns for welfare, and justice, of the Tri-Council Policy Statement were enacted throughout the study (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, & Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, 2018). An incentive in the form of a $25 gift card was provided to caregivers who participated in the study.

Findings

Demographic Characteristics

There was variation in caregiver characteristics such as sex, age, level of education, and years of being a caregiver. See Table 2 for the demographic characteristics of caregivers and persons with dementia. There were equal numbers of male and female caregivers (50%). The mean age of caregivers was 56.5 years, with a standard deviation (SD) of 12.1. Most of the caregivers were caring for a parent (66.7%). The sample was Caucasian, except for one participant. All except one participant were currently caring for a family member. All caregivers had completed post-secondary education with half of them having completed a bachelor’s degree (50%). More than half of the caregivers were working part time or full time (66.7%). Caregivers reported few chronic conditions (e.g., chronic musculoskeletal pain, osteopenia, gastrointestinal issues) with most of them reporting one or two chronic conditions (66.7%). Most caregivers had been in the role for many years, with the mean number of years in the caregiver role being 4.9 years (SD = 3.2). All caregivers reported providing support for persons with dementia in the form of advice or emotional support and assistance with daily activities such as household chores, transportation, and banking. All except one caregiver reported providing assistance with personal care such as assistance with mobility, providing nutrition, dressing, and bathing. In terms of the demographic characteristics of the persons with dementia being cared for, the mean age was 78.3 years (SD = 7.6). Persons with dementia had on average three to five chronic conditions (e.g., depression/anxiety, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, stroke, osteoporosis, chronic musculoskeletal pain) (85.8%).

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of caregivers (n = 6)

Note. The total percentages for some categories do not equal 100% because of rounding of values. One caregiver was a former caregiver, as both parents had died within the last 5 years. The age and number of years diagnosed with dementia at the time of their death were included. The total number of persons with dementia was seven.

SD = standard deviation.

Themes

In this section, themes that arose from analysis of the notes and transcripts from the workshop sessions are presented. First, codes and themes that emerged from the data were grouped under: perceived need for adapting the Namaste Care approach for home use. Next, themes for suggested adaptations to the Namaste Care intervention based on the Stirman et al. (Reference Stirman, Miller, Toder and Calloway2013) framework were presented: (1) modifications for the implementation of Namaste Care sessions, (2) contextual modifications for delivering Namaste Care, and (3) nature of Namaste Care content modifications. The framework category regarding who was responsible for suggesting modifications has been explored by describing the caregivers in the demographic characteristics section. Finally, codes and themes for adapting training as an implementation strategy based on the Stirman et al. (Reference Stirman, Miller, Toder and Calloway2013) framework were categorized under: modifications for training in Namaste Care. See Table 3 for an overview of categories and themes. Quotes are labelled with “CG” for caregiver. Table 4 provides a comparison of the similarities and differences between the original Namaste Care program intended for LTC use and how caregivers in the current study envisioned the adaptation of Namaste Care for home use.

Table 3. Overview of themes

Note. The Stirman et al. (Reference Stirman, Miller, Toder and Calloway2013) framework was used to guide theme development.

Table 4. Comparison of Namaste Care in long-term care (LTC) versus a home setting

Note. Information on Namaste Care was referenced from books by Simard (Reference Simard2013) and Kendall (Reference Kendall2019).

Perceived need for adapting Namaste Care for home use

Caregivers were optimistic that Namaste Care could lead to positive impacts for persons with dementia. They recognized the value of adapting Namaste Care so that it could be used in a home setting. Caregivers involved in adapting Namaste Care perceived that it could: (1) help to relieve frustration during interactions, (2) Enhance daily activities through creative ideas, and (3) increase connections between persons with dementia and caregivers.

Help to relieve frustration during interactions. Caregivers reported feeling frustrated at times when interacting with family members. “But when she is in that very stubborn kind of framework, it just makes it so much more harder and frustrating and tiring, for sure” (CG-102). Namaste Care was perceived as an approach that allowed both persons with dementia and caregivers to take time to enjoy an activity together such as completing a puzzle. The approach was perceived as having the potential to improve interactions. “I could try doing the puzzle with mom with CBC radio in the background and making it nice and calm. This is a really nice way to interact with her” (CG-102).

Enhance daily activities through creative ideas. The core elements of Namaste Care resonated with caregivers, and most reported doing some of the activities (e.g., dancing, singing, holding hands) already but wanted to learn how to implement more activities through creative means. “I do a little bit, but I would like to do more” (CG-104). One caregiver suggested using a heating pad as a way to provide comfort for her mother, and other caregivers agreed with the idea. “I know that [heat pad] works very well for my mom if she has pain on her back or on her leg. So that would probably be part of the comfort thing” (CG-102). Caregivers had an understanding of preferences of their family members, which in turn informed their selection of comforting activities.

Increase connections between persons with dementia and caregivers. Caregivers perceived that Namaste Care could be used to increase meaningful connections between persons with dementia and caregivers. The program was viewed as a way to strengthen familial relationships and also decrease agitation for persons with dementia.

I think it does make a difference for so many reasons. Like even to keep them less agitated, sort of a connection as well. I’m always holding my dad’s hand…And it seems he is much more calm. (CG-104)

Modifications to the implementation of Namaste Care sessions

Modifications were suggested for the implementation of Namaste Care sessions for caregivers and for persons with dementia. Themes were: (1) gradually increasing Namaste Care sessions and (2) using shorter and less frequent sessions to the fit the realities of caregiving.

Gradually increasing Namaste Care sessions. Caregivers were concerned about how interested their family members might be in participating in Namaste Care sessions. Some were hesitant to use the adapted program more frequently at the start out of fear that persons with dementia might not like certain activities. This hesitancy could also be the result of the initial comfort level of caregivers in using the approach. Caregivers who had been in the role for a number of years were more inclined to suggest using the adapted Namaste Care program daily; however, some felt more cautious and suggested starting the adapted program twice a week.

I think for me. It’s just depending on how interested my mum would be. I think I could probably try a minimum of two times a week and maybe do it for like an hour, an hour and a half and see how it goes. (CG-102)

Using shorter and less frequent sessions to fit the realities of caregiving. Caregivers perceived that implementing Namaste Care for 1–2 hours at a time was not practical. Many of the caregivers were working and responsible for most if not all household activities. Caregivers also reported that their family members’ attention span may not last for 1 hour, their period of alertness may be brief, or they may not be able to sit still for long periods. Caregivers perceived that for the adapted Namaste Care program to work for them they needed more flexibility in how often and for how long they should use the adapted program.

It really depends on the situation at hand. If, my mom is having a good week with no falls or no reaction to medications then three times a week could be workable, but if she is falling twice a week and if she is having problems with medication even once a week may be stretching it. So, it really depends right. I think for my scenario at least it has to be more flexible than you would have to do it two times a week or three times a week. (CG-106)

The changes in persons with dementia could be unpredictable from week to week, and even day to day, so flexibility in delivering Namaste Care was perceived as key. Setting together a proposed minimum number of sessions of two times a week and a minimum length of session of 20–30 minutes were perceived as suitable for most caregivers. “…but I wouldn’t see it being much longer than 20 to 30 minutes” (CG-103).

Contextual modifications for delivering Namaste Care

The adapted version of Namaste Care underwent a few context modifications (i.e., personnel, population, and setting) so that it better reflected the needs of caregivers in a home setting. In the adapted version: (1) persons delivering Namaste Care were family and friend caregivers rather than LTC health care providers, (2) recipients included older adults with moderate dementia in addition to those with advanced dementia, and (3) Namaste Care was delivered in any room of the home. The themes were: (1) caregivers are highly involved in supporting persons with dementia daily, (b) older adults with moderate dementia can also benefit from Namaste Care by tailoring Namaste Care activities, and (3) Namaste Care is delivered wherever it is convenient.

Caregivers are highly involved in supporting persons with dementia daily. Compared with care providers who are responsible for delivering Namaste Care in LTC at set times, family caregivers in the community are taking on multiple different tasks throughout the day to support persons with dementia. “I have just been slowly taking on tasks. I live with her and so we formalized that term caregiver with her and the physicians in June. You know, I’ve been a caregiver for a long time, but officially since June” (CG-102). Bearing in mind that caregivers are responsible for providing assistance with daily activities, the suggested adaptations for Namaste Care were intended to increase the likelihood for caregivers to adopt the program.

Older adults with moderate dementia can also benefit from Namaste Care by tailoring Namaste Care activities. Although the original Namaste Care program was designed to help fill a gap in programs for persons with advanced dementia, caregivers perceived that older adults with moderate dementia could also be positively impacted through the approach. Caregivers perceived that tailoring activities for each individual with dementia was key in delivering Namaste Care. Caregivers perceived that it is essential to have room for flexibility in tailoring activities for different stages of dementia, abilities, preferences, and needs. “I think that’s important because what will work for one [person] won’t work for another” (CG-104).

Namaste Care is delivered wherever it is convenient. Rather than have a designated room for Namaste Care sessions such as would be done in LTC, caregivers perceived that the adapted Namaste Care program should be taken to their family members. This was perceived as a way to minimize disruptions of routines and reduce the burden of transferring less mobile or resistant family members from one room to another. Caregivers recommended flexibility in selecting where Namaste Care would take place in the home.

I wouldn’t have a particular room, but I would either use the living room, where we sit after a nap. I would use that as one spot and the other spot might be in the family room where we go to sit and watch TV. I could do something there. Or the bedroom, often I’m doing a massage on his feet and legs before he even gets out of bed in the mornings. So I could do something in that room as well with the diffuser. (CG-101)

Nature of Namaste Care content modifications

Regarding content modifications to Namaste Care, suggested changes were adding activities and being flexible in how Namaste Care is used. Specific themes were: (1) asking persons with dementia to reciprocate an activity; and (2) integrating Namaste Care into daily care routines.

Asking persons with dementia to reciprocate an activity. Caregivers recommended that persons with dementia be encouraged to engage in the adapted Namaste Care program by performing activities in return for caregivers. This ensured that persons with dementia were still being perceived as able to provide valuable contributions and reminded them of their identity within the family.

I think that’s important to kind of be two-fold. Like my dad likes to help out. So I was thinking for the hand massage like I do it for him, but then I’ll say “ok dad do it for me too”, right? Because he’s always wanting to help out and do something. So kind of gives him something to do but also soothes him at the same time. So that’s what I’m hoping that that could be a possibility. (CG-104)

This idea also provided a reflection of the nature of the adapted version of Namaste Care, which focuses on impacts on both caregivers and persons with dementia.

Integrating Namaste Care into daily care routines. Caregivers did not perceive Namaste Care as being an approach completely separate from what they were already doing with their family members. Rather than viewing Namaste Care as a new activity, it was perceived as a way to enrich daily interactions and as an opportunity to turn them into a routine.

The other thing that I wanted to mention is that, for me, an integrated solution is ideal. Meaning that instead of spending a block of time and it also depends on what those… Namaste Care pieces are…But for the other pieces, like touch, aromatherapy and massage, all those other things, if you are doing as direct service, you can probably integrate that in, weave it into your other daily activities. (CG-105)

Integrating Namaste Care into daily activities was perceived as being a more effective strategy to enable caregivers to use the adapted program, as this is more realistic than trying to find additional time to implement it.

Modifications for training in Namaste Care

Modifications were also suggested for the training content and format. Caregivers recommended the incorporation of additional specific information on Namaste Care activities in the training content, a more practical training format, and an informal assessment of caregivers to support uptake of the adapted Namaste Care program. Themes were: (1) wanting to know how persons with dementia might respond to Namaste Care activities, (2) identifying videos demonstrating hands-on activities, (3) using Zoom as a good alternative to in-person training, (4) limiting repetition through a shorter training session, and (5) maximizing uptake of Namaste Care by exploring caregivers’ understanding of dementia.

Wanting to know how persons with dementia might respond to Namaste Care activities. Caregivers sought written information about signs that Namaste Care activities are comforting for persons with dementia so that they could be reassured “whether it’s working or not working” (CG-104). Responses to activities, especially non-verbal responses, were perceived by caregivers to be important indicators that demonstrated their success in connecting with their family members. “Just to know or understand that you’re actually managing to get through to her” (CG-103). Caregivers of persons with dementia in the moderate stages were concerned about reactions to activities being too simple, and sought clear guidance on tailoring activities.

I think also some instructions of what to expect in terms of how typically people with Alzheimer’s or dementia will react to an activity or what would be too complicated or maybe too simple. Like maybe ways to break down an activity so it is a little more digestible. So I had tried a puzzle last year with my mum because we used to do puzzles all the time, but it was too complicated. So this weekend I picked up a 500-piece puzzle and it seems to be just the right complication. (CG-102)

Identifying videos demonstrating hands-on activities. For activities requiring manipulation, such as hand or foot massages and range of motion exercises, caregivers recommended integrating videos during Namaste Care training. These activities were perceived as requiring skilled movements learned through audiovisual means. “And if you are able to provide those [step-by step sheets] and/or video for that massage piece or any of the other things, but clearly with massage that’s technical in nature that would really, really be great” (CG-105).

Using Zoom as a good alternative to in-person training. Because of the unpredictable course of the COVID-19 pandemic, caregivers perceived that Zoom was a good option for Namaste Care training, as it provided an audiovisual component. “I think Zoom probably because you could visualize” (CG-104). Videoconferencing was perceived as providing the best simulation of an in-person Namaste Care training session and “you can demonstrate certain things” (CG-102).

Limiting repetition through a shorter training session. Caregivers perceived that many of the Namaste Care activities were familiar to them, and recommended a shorter training session than the original full day-training session conducted in LTC. “The people that are starting the program, new people to this, I think an hour is probably plenty. Now, I don’t know if I would need that much time. Just because I do some of the stuff already” (CG-101). Caregivers involved in adapting Namaste Care were also looking forward to implementing the adapted program in the next part of the study, and felt that some information would be repetitive if brought up again during training. Some caregivers perceived that the length of the training session should depend on the learning needs of caregivers and that it would be difficult to set a fixed timeline for all. “I will have questions and especially just relating to my mom’s situation and my own personal context. Sixty minutes is great, if longer even better” (CG-106).

Maximizing uptake of Namaste Care by exploring caregivers’ understanding of dementia. Caregivers perceived the need to ensure that training would be tailored to caregivers’ learning needs by exploring caregivers’ overall understanding of dementia. “I think maybe the better approach would be before starting any Namaste Care program with any pre-conceived notions or approaches, the family is assessed” (CG-105). Assessing families prior to starting Namaste Care training was seen as a way of ensuring that they understood the value of sensorial activities and encouraging them to implement the approach.

Discussion

This study is the first to present both detailed descriptions and explanations of suggested adaptations for the Namaste Care intervention for use by caregivers of community-dwelling older adults with moderate to advanced dementia, and suggested training procedures. Dalkin et al. (Reference Dalkin, Lhussier, Kendall, Atkinson and Tolman2020) explored the use of Namaste Care in home settings but did not provide a comprehensive description of how Namaste Care was adapted from an LTC context for a home setting. The authors did state that the dose of the intervention was modified from the original Namaste Care program, as it was delivered weekly by volunteers for 2 hours at a time (Dalkin et al., Reference Dalkin, Lhussier, Kendall, Atkinson and Tolman2020). Because of the lack of studies focused on home-based interventions for caregivers of older adults with moderate to advanced dementia, this group of caregivers was targeted to ensure that modifications would reflect their unique realities of caregiving.

By using a recognized framework for modifications (Stirman et al., Reference Stirman, Miller, Toder and Calloway2013) to guide the adaptation process recommended adaptations to Namaste Care were identified while keeping intact the core components of the program: (1) using a person-centred approach, (2) incorporating comfort and pain management, (3) scenting a room, (4) playing relaxing/upbeat music, (5) providing touch activities, (6) offering beverages and snacks, (7) encouraging range of motion activities, and (8) providing reminiscence activities (e.g., photo albums, conversations about life stories) (Kendall, Reference Kendall2019). These components were left intact, because caregivers perceived that all of them were important in supporting the quality of life of persons with moderate to advanced dementia. Caregivers perceived that the successful implementation of these components depended on flexibility in tailoring the components of the program to the unique preferences and abilities of persons with dementia. The suggested changes to the original Namaste Care program, such as adding activities and including older adults with moderate or advanced dementia, were therefore considered to be minor. Suggested changes for Namaste Care training were also minor. Providing training virtually was seen as necessary when implementing Namaste Care during the COVID-19 pandemic, and may be a feasible approach for the future as well.

Key findings of the study were that caregivers felt fully engaged in the adaptation process because the core components of Namaste Care were not perceived by caregivers as being completely unknown to them, and they recognized the value of Namaste Care in making meaningful connections. Having had previous experience in implementing sensorial activities at home helped to ease the way for caregivers in understanding what adaptations were needed to ensure that the intervention was appropriate for caregivers in the home setting. They felt comfortable and confident in making recommendations to improve the program as well as in sharing their experiences of what activities worked for them. Findings revealed that caregivers were receptive to delivering Namaste Care at home, but modifications would need to be made to ensure flexibility in delivery and that activities could be tailored to the needs of each person and the realities of the caregiver’s situation. Caregivers perceived the need to be flexible in when, how long, and where Namaste Care should be used. Providing room for caregivers to tailor the Namaste Care activities was perceived as important, as not all persons with dementia will respond to activities in the same manner.

The present study actively engaged caregivers to adapt Namaste Care for home use to ensure that it would fit within a new context. Findings related to the strategies and process used to meaningfully engage caregivers in adapting the Namaste Care program are reported elsewhere. Walshe et al. (Reference Walshe, Kinley, Patel, Goodman, Bunn and Lynch2019) found similar findings when they explored the process and experiences of co-designing the Namaste Care intervention and its training procedures for LTC with multiple stakeholders including health care providers, members of a public involvement panel, and caregivers. The program was to be delivered in nursing care homes in the United Kingdom, and adaptations were perceived to be necessary to reflect the language and culture of the new context. Engaging stakeholders in reviewing the Namaste Care training guide and altering the program based on direct feedback was found to be an effective approach to ensure that the program would be acceptable in an LTC context. Compared to the present study however, Walshe et al. (Reference Walshe, Kinley, Patel, Goodman, Bunn and Lynch2019) had only one family caregiver from an LTC home with prior knowledge of Namaste Care participate in workshops to co-design Namaste Care. In addition, five members of a patient and public involvement panel, which may have included some family members, were asked to discuss and comment on the final refinement of Namaste Care program resources. The limited involvement of family caregivers in co-design may prevent them from taking on a more active role in participating in Namaste Care sessions in LTC. They may not view Namaste Care as applicable to or feasible for them.

In the present study, caregivers emphasized the importance of tailoring the adapted Namaste Care program for older adults with dementia and caregivers based on their unique situations. Tailoring also applied to Namaste Care training, as not all caregivers have the same understanding of dementia and therefore may have different learning needs. Duggleby and Williams (Reference Duggleby and Williams2016) suggest that when selecting interventions to adapt, it is important to ensure that the interventions could be tailored on an individual level. One of the important attributes of Namaste Care is that activities can be tailored to individuals based on unique life stories, likes, dislikes, abilities, and needs (Simard, Reference Simard2013). It is important to ensure that interventions can meet the needs of diverse caregivers and older adults with dementia while still maintaining their original effectiveness when transferred to a home setting. Tailoring can also ensure that interventions can be used in a flexible manner while taking into consideration personal values and choices (Collado, McPherson, Risco, & Lejuez, Reference Collado, McPherson, Risco and Lejuez2013).

Furthermore, using meticulous planning in qualitative research when making adaptations to interventions has been found to ensure that interventions are feasible and acceptable, and have the potential for positive impacts on a new population (Duggleby et al., Reference Duggleby, Peacock, Ploeg, Swindle, Kaewwilai and Lee2020). In the present study, the use of qualitative research combined with careful planning (Card, Solomon, & Cunningham, Reference Card, Solomon and Cunningham2011) provided rich descriptions and explanations of why caregivers proposed specific adaptations. Such detailed information may not have been found if the Stirman et al. (Reference Stirman, Miller, Toder and Calloway2013) framework was simply used to classify modifications without the use of inductive analysis to reveal themes that can support the rationale for adaptation. A better understanding of the current context of caregiving was gained through qualitative research and determining how interventions can be used to support caregivers.

A comprehensive process in adapting Namaste Care for home use by caregivers was selected to enhance the uptake of the intervention and its effectiveness in the next part of the study, which consists of a pre-test/post-test feasibility study. Using the Stirman et al. (Reference Stirman, Miller, Toder and Calloway2013) framework in the current study helped to ensure that suggestions for modifications to the Namaste Care program provided by caregivers were documented in detail to inform the adapted program, and that all aspects of an intervention were considered, including its training processes. This type of approach to adapt interventions has been found to be successful in another study in meeting key objectives for adapting the intervention such as improving the fit for stakeholders, engaging intended providers of an intervention, and increasing intervention effectiveness in a trial (Chlebowski, Hurwich‐Reiss, Wright, & Brookman‐Frazee, Reference Chlebowski, Hurwich‐Reiss, Wright and Brookman‐Frazee2020).

Moreover, the workshop sessions in the current study provided an opportunity for caregivers to reflect on their caregiving experience in making recommendations for adapting Namaste Care. Caregivers were encouraged to think about how they felt about the caregiving role and how Namaste Care could bring a positive approach to care. Carbonneau, Caron, and Desrosiers (Reference Carbonneau, Caron and Desrosiers2011)) found that the perceptions of caregivers who participated in a leisure education program adapted for persons with dementia evolved to help them perceive their role as a positive opportunity rather than a burden. Although caregivers in the current study did not yet participate in the implementation of the adapted version of Namaste Care, talking about sensorial activities and learning about ideas discussed in the group gave them hope that there were still things that they could do to support the quality of life of their family members.

Including both men and women in the current study sample ensured that perspectives were diverse in terms of perceived gender roles and caregiving activities. Male caregivers have been found to assume a more task-oriented approach when providing care than women do, and male caregivers may require more support to adjust to the caregiving role, as it has been traditionally regarded as feminine work (Robinson, Bottorff, Pesut, Oliffe, & Tomlinson, Reference Robinson, Bottorff, Pesut, Oliffe and Tomlinson2014). Learning about the perspectives of male participants regarding how to adapt Namaste Care provided a better understanding of their perceptions of meaningful leisure activities for persons with dementia, and how the training should be conducted to best support them in delivering the adapted program. Participants were also of various ages. Including participants of different ages provided a better understanding of the experiences and unique challenges of younger and older caregivers in supporting older adults with moderate to advanced dementia, and how they perceived the delivery of Namaste Care. Older caregivers are often of similar ages as persons with dementia, and experience greater limitations in providing hands-on care than do younger caregivers, because they may have lower energy levels and chronic conditions (Greenwood, Pound, Brearley, & Smith, Reference Greenwood, Pound, Brearley and Smith2019). In the present study, younger caregivers were still working while caregiving. When compared with older caregivers, they experienced more mental health distress related to addressing responsive behaviours such as yelling, hitting, or restlessness expressed because of feelings of boredom, hunger, or thirst (Koyama et al., Reference Koyama, Matsushita, Hashimoto, Fujise, Ishikawa and Tanaka2017).

This present study highlights important policy and research implications for designing interventions. Many ideas suggested by caregivers in adapting Namaste Care were unique and valuable, and the research team alone would not have been able to come up with such recommendations. In terms of policy implications, there is a need to ensure that the input and feedback of persons with lived experience are sought when developing or adapting interventions. This should be a mandatory requirement when designing or modifying interventions, as patient or family involvement is a growing area of health services research with many advantages. For example, involving caregivers of persons with dementia in developing interventions provides a comprehensive understanding of the perspectives of end-users, and their ideas and experiences inform the tailoring of intervention materials while providing a more accurate representation of the needs of caregivers (Hales & Fossey, Reference Hales and Fossey2018). It is essential for researchers and policy makers to listen to and incorporate what caregivers are sharing in terms of what they need because the ultimate goal of creating these interventions in the first place is to support them as best as possible.

From a research perspective, many interventions are being adapted in the middle of implementation leading to negative repercussions for intervention fidelity and favorable outcomes (Escoffery et al., Reference Escoffery, Lebow-Skelley, Udelson, Böing, Wood and Fernandez2019). Findings of the present study have research implications in terms of saving time for researchers by adapting interventions with caregivers prior to their implementation. Potential funders of intervention studies should be recommending that this type of research involve stakeholders in some capacity whether it is in creating, adapting, reviewing, or testing an intervention prior to its implementation to enhance its relevance. The next steps for the current program of research are to further adapt the Namaste Care program based on the suggested modifications provided by caregivers and to test the new intervention with caregivers of community-dwelling older persons with moderate to advanced dementia living at home. Prior to implementing the program, further modifications to fit the unique context of caregivers will be made by considering the relationship between caregivers and persons with dementia, ethnic and cultural values, and areas where further training is required.

Study Strengths and Limitations

Study limitations include a small sample size, lack of ethnically diverse participants, and inclusion of only participants residing in Ontario, Canada. With the small sample size and lack of ethnic and cultural diversity in the sample, further adaptations to the Namaste Care program may be required to suit the unique values and context of multicultural groups. One of the key suggestions shared by participants was to ensure flexibility in how to deliver the adapted program. This may be an area to acknowledge when offering the program to diverse groups as well as when providing training for caregivers. Despite the lack of ethnic and geographical diversity in the study sample, there were an equal number of women and men who participated in the workshops, and the ages of participants varied, making findings more transferrable. Another limitation was that this study was not truly a “co-design” study, as caregivers were not involved in developing research questions, study design, establishing study outcomes, or designing an entirely new intervention. Nevertheless, caregivers were actively engaged in making recommendations for how Namaste Care could be adapted for their use in home settings, and in the training.

Conclusion

This study provided a comprehensive description and explanation for suggested adaptations for Namaste Care in collaboration with caregivers of community-dwelling older adults with moderate to advanced dementia. Findings revealed that caregivers perceived Namaste Care as fitting into their usual interactions and activities and as an approach to strengthen relationships between persons with dementia and family members. Caregivers stressed the importance of tailoring activities and training to individual needs and situations in order to maximize the use of the adapted Namaste Care program in a home setting. An output of the adaptation process consisted of a training guide for delivering the adapted version of Namaste Care at home, which reflected the ideas and suggestions provided at the workshop sessions. One of the top 10 research priorities for dementia research in Canada is caregiver support (Bethell et al., Reference Bethell, Pringle, Chambers, Cohen, Commisso and Cowan2018). Evaluating family-centered interventions that are adaptive to conditions, needs, and stages of a health condition was similarly identified as a top 10 research priority during a summit on research priorities in caregiving (Harvath et al., Reference Harvath, Mongoven, Bidwell, Cothran, Sexson and Mason2020). In responding to these priorities, the next steps for the study are to implement and evaluate the adapted Namaste Care program for caregivers at home, which can be tailored when delivered by caregivers in a home setting through a feasibility study. Further adaptations to the adapted Namaste Care program may also be recommended by caregivers following the feasibility study based on real-world experiences in implementing the approach. The adapted Namaste Care program has the potential to support older adults with dementia to remain at home by enhancing the skills of caregivers and delaying the need for LTC.

Acknowledgments

We thank caregivers who participated in the study.

Funding

This research is supported through an Alzheimer Society of Brant, Haldimand Norfolk, Hamilton, and Halton research grant awarded during the Spring cycle of 2020, and a Canadian Gerontological Nursing Association research grant awarded during the Spring of 2021.