Introduction

Most medical trainees are members of Generation Y. This cohort, born in the 1980s and 1990s, is characterized as being more technologically savvy than preceding generations.Reference Weiler 1 They also increasingly use social media (defined as the sharing of information and ideas within an online community) to communicate. The health profession trainees in this cohort increasingly rely on the Internet and other technology to retrieve medical information.Reference Weiler 1 – Reference Matava, Rosen and Siu 5

Online educational resources (OERs) are becoming increasingly prominent in medical education. Initially, these resources were paid for by institutions (e.g., UpToDate) and individuals (e.g., the podcast EM:RAP); however, free OERs are growing in popularity.Reference Nickson and Cadogan 6 – Reference Mallin, Schlein and Stroud 8 Emergency medicine (EM) has become a leader in this area.Reference Nickson and Cadogan 6 – Reference Mallin, Schlein and Stroud 8

Understanding whether learners and their teachers differ in use and choice of free resources is an important next step to comprehending the impact of OERs on medical education.Reference George and Green 9 , Reference Cheston, Flickinger and Chisolm 10 Free OERs vary in content; some are highly referenced, registered with universities, incorporate peer-review processes, and offer continuing medical education credit, whereas others propagate inaccurate information.Reference Brabazon 11 , Reference Thoma, Chan and Desouza 12 Generational trends suggest that the current cohort of EM learners will be drawn to these nontraditional resources to a greater extent than their teachers, but how students and teachers choose resources has not been well defined.Reference Weiler 1 – Reference Barker, Wehbe-Janek and Bhandari 3 To teach appropriate stewardship of this new and evolving repository of educational material, the use of free OER must first be described and quantified.

The primary purpose of this study was to quantitatively describe free OER use by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC) EM residents. Secondary objectives were to compare the use of OERs between RCPSC-EM residents and program directors (PDs) and to investigate the effect of OERs on the use of peer-reviewed literature. A survey methodology was selected to explore these questions and to allow data to be collected from this large, distributed population in a generalizable, cost-effective, and standardized fashion.

Methods

This study received ethical approval from the Research Ethics Board of McMaster University. Survey results were reported in accordance with best practices as outlined in Academic Emergency Medicine.Reference Mello and Merchant 13

The survey was designed by consensus of the five authors who were informed by similar surveys in anesthesia and EM residents.Reference Matava, Rosen and Siu 5 , Reference Mallin, Schlein and Stroud 8 , Reference Wong 14 It was hosted on Fluid Surveys. The program director and a resident from postgraduate years one through four from the University of Saskatchewan RCSPC-EM residency program completed a pilot survey between September 27, 2013 and October 10, 2013. Their qualitative feedback was used to clarify questions and refine content. The final version of the survey was translated into French by a bilingual co-author (Migneault). The English version is available in Appendix 1.

A survey link was distributed by email to RCPSC-EM residents and PDs of the 14 training programs in Canada. Respondents were recruited using a modified Dillman methodReference Hoddinott and Bass 15 that involved a maximum of five emails from multiple sources, including the director of the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians resident section, chief residents, and PDs. Responses were collected from November 19 to December 31, 2013. All responses were anonymous, and completion of the survey was voluntary. Entry into a draw for a $500 gift certificate was used as an incentive for survey participation.

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Version 21.0 (SPSS IBM, New York, USA). The chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test (<5 variables) were used to calculate p-values for categorical variables. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data entered into incomplete surveys were included in the statistical analysis.

Results

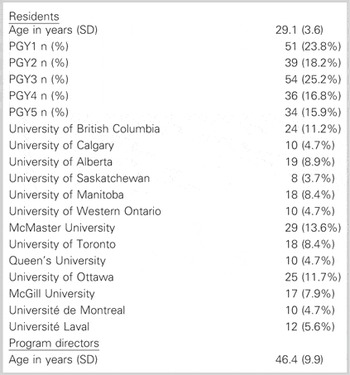

As outlined in Figure 1, 214/350 (61%) of RCPSC residents and 11/14 PDs (79%) participated in the study. There were three incomplete responses included in the analysis, for which participants entered demographic information and answered some questions but did not reach the final page of the survey. The demographics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1 Flow diagram of study participation and survey completion.

Table 1 Demographics

Free OER use: frequency, type, and comparison to traditional resources

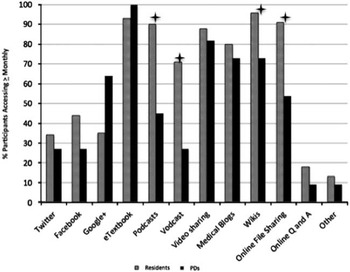

Residents used wikis (95%), e-textbooks (93%), file-sharing sites (91%), podcasts (90%), video sharing sites (88%), medical blogs (80%), and vodcasts (71%) at least monthly. Textbooks (86%), subscription-based resources (65%), and podcasts/vodcasts (40%) were ranked as the top three resources that contributed most to a resident’s education, more frequently than primary literature (33%), e-textbooks (26%), medical blogs (26%), and wikis (11%).

Comparison of the types of OERs used by RCPSC-EM residents and PDs (Figure 2), respectively, showed that residents over PDs used podcasts (90% v. 45%, p<0.01), wikis (96% v. 73%, p<0.01), online file-sharing sites (91% v. 54%, p<0.01), and vodcasts (71% v. 27%, p<0.01) more frequently.

Figure 2 Monthly or more frequent use of OERs by residents compared to PDs (*p<0.05).

Reason for free OER use

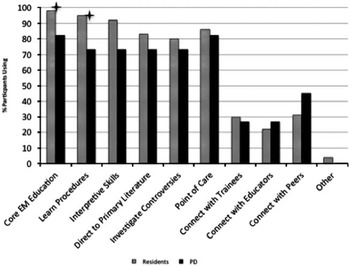

OERs were used by residents and PDs, respectively, for a wide variety of purposes (Figure 3), including core EM education (98% v. 82%, p=0.01), procedural skills training (95% v. 73%, p=0.01), diagnostic/imaging interpretation (92% v. 73%, p>0.05), answering questions at the point of patient care (86% v. 82%, p>0.05), and investigating controversial topics in EM (82% v. 73%, p>0.05).

Figure 3 Purpose of OER use by residents compared to PDs (*p<0.05).

Resource selection

Figure 4 compares the factors that residents and PDs used for selecting resources. The factors that ranked more frequently as important or very important by residents when compared to PDs, respectively, were entertainment value (41% v. 9%, p=0.02) and peer referral (50% v. 36%, p=0.05). Inclusion of references was not statistically different between the groups, but only 77% of residents compared to 100% of PDs thought references were important or very important.

Figure 4 Perceived value of factors important for selecting OERs by residents compared to PDs (*p<0.05).

Free OERs and peer-reviewed literature use

Overall, residents (80%) and PDs (73%) self-reported that free OERs increased their use of primary literature. Both groups (72% residents, 55% PDs) felt that they read more studies in full as a result of OERs, and both groups (79% residents, 73% PDs) felt that they read more critical appraisals of primary studies. A minority of residents (25%) and PDs (27%) access more than half of the articles cited by OERs.

Discussion

This study found that RCPSC-EM residents and PDs use free OERs regularly. Residents used nearly all OERs more frequently than PDs and considered different factors when selecting resources. OERs increased self-reported primary literature use. Despite prevalent OER use in our study, residents ranked textbooks and subscription-based resources as their top information sources. These results are similar to other reports of OER use by residents.Reference Matava, Rosen and Siu 5 , Reference Mallin, Schlein and Stroud 8 , Reference Wong 14

There were several differences between the types of OERs used by residents and PDs. The use of podcasts was the greatest discrepancy with 90% of residents and 45% of PDs listening to them monthly. This difference is important because we also found that learners value direction from faculty in selecting resources. If PDs are not frequently using podcasts or other OERs, they may be ill equipped to suggest appropriate resources. It will be increasingly important for educators to understand the usage patterns and motivations behind learner use of OERs.

Residents’ and PDs’ opinions also differed on the importance of entertainment value and referenced content when selecting OERs. The increased value placed on entertainment by residents is congruent with a recent report highlighting how Generation Y EM learners are most receptive to education that is fast-paced and entertaining.Reference Santella, Kaneva and Petrucci 16 , Reference Moreno-Walton, Brunett and Akhtar 17 OERs more frequently offer this “edu-tainment” factor than traditional educational resources. The increasing importance of engaging and entertaining educational materials is a trend that warrants recognition by educational leaders.Reference Moreno-Walton, Brunett and Akhtar 17 , Reference Sandars and Morrison 18 The importance of references in the selection of OERs also differed. All PDs valued appropriately referenced OERs, whereas nearly a quarter of residents did not. Although this trend was not statistically significant, efforts to further understand this discrepancy should be a focus of both formal research and discussions between residents and faculty.

By recognizing these differences in OER resource selection, PDs may be better equipped to encourage high quality resource choice among their trainees. Interestingly, a recent survey of RCPSC-EM PDs endorsed the use of high quality OERs and highlighted the importance of developing residents’ abilities to critically appraise them.Reference Bednarczyk, Pauls and Fridfinnson 19 These skills are important because the quality of information delivered in OERs can be a variable. For example, the reliability of wikis for medical information is unclearReference Lavsa, Corman and Culley 20 , Reference Haigh 21 with one study showing that EM trainees more frequently answered clinical questions incorrectly with greater confidence when using Google, which often links to wikis as a resource.Reference Krause, Moscati and Halpern 22

One of the strongest criticisms of traditional resources (i.e., textbooks, systematic reviews, and subscription-based) is that they are quickly outdated. Subscription-based resources and e-textbooks have considerable variability in the proportion of updated topics with 52% of 200 articles on UpToDate classified as out of date.Reference Jeffery, Navarro and Lokker 23 If even continuously updated resources are potentially expired, it follows that printed textbooks are even more outdated. Systematic reviews are subject to similar limitations, with 7% in need of updating at the time of publication.Reference Shojania, Sampson and Ansari 24 OERs have the potential to address this limitation because they can be published quickly and are easily updated.

The delayed update of traditional resources would be less of a problem if it was possible to read all of the latest primary literature. However, this is time-consuming with estimates suggesting a number needed to read 13–14 articles from the top 20 journals to find one practice-changing article.Reference McKibbon, Wilczynski and Haynes 25 OERs may ameliorate this problem by delivering important information from and increasing awareness of the literature in a timely and digestible fashion. In our study, both residents and PDs reported increased use of primary literature related to OER use, which may be due to increased awareness of relevant articles.

Weighing the strengths and weaknesses of any learning tool should be the shared responsibility of residents and their teachers. Free OERs are no different, but our study demonstrates discrepancies in OER use and the factors that residents and PDs see as important in this decision-making process. OERs offer unique benefits over traditional resources, including ease of access, frequent updates, real-time feedback from a worldwide audience, and the opportunity for active learning through content creation and interaction with content producers. The asynchronous learning model, central to OERs, makes it a natural choice for Generation Y learners who value accessibility highly when seeking information.Reference Weiler 1 , Reference Sandars and Morrison 18 Those involved with residency education need to be aware of these benefits and also be prepared find ways to help learners identify the highest quality resources. This will require knowledge of the ever-increasing body of available free OERs.

Limitations

Our survey methodology was susceptible to various forms of bias (e.g., nonresponse, recall, and social desirability); however, many forms of validity evidence were also inherent to our study design. The survey content was based on previously used instruments, the survey was piloted with a representative group of residents and educators, the study population was well defined, reliable contact information was available for all potential participants, the response rate was relatively high for a national survey,Reference Barker, Wehbe-Janek and Bhandari 3 , Reference Matava, Rosen and Siu 5 , Reference Mallin, Schlein and Stroud 8 and residents from all programs and regions of Canada were included.

A second limitation is the large number of comparisons between the two populations, which makes the results susceptible to a type I error. However, the majority of differences that we found were highly significant (generally p<0.01). The small population of PDs also put the study at risk of a type II error.

It is arguable that the chosen study population and focus on free OERs limit the generalizability of our results. Exclusive study of RCPSC-EM residents and PDs means that the results are not fully generalizable to other residency programs, but it did allow for specificity to our population of interest. PDs are a specific and unique population of educators and may not be representative of all teachers involved in the education of RCPSC-EM residents. It was not feasible to survey all educators, so PDs were chosen because they are educational opinion leaders who have consistent contact with the surveyed population of residents and who are responsible for developing longitudinal resident curricula. We focused on free OERs because paid OERs are better established, less accessible, seem to face less scrutiny, and have had less explosive growth.

We were unable to provide descriptive interpretation of our results because the survey included only closed-ended questions. Open-ended questions were not included because it was felt that they would decrease survey completion.

Conclusion

This study informs educators about residents’ OER use. Its findings should stimulate discussions about OER use and their critical appraisal within EM education. EM residents use OERs frequently for general EM education, procedural training, and learning interpretive skills. Relative to their PDs, residents use OERs more frequently and place greater value on entertainment. Self-reported data suggest that OERs increase the use of peer-reviewed literature for both residents and PDs. Future research that prospectively assesses residents’ use of OERs would deepen our understanding of their role in resident education.

Competing interests: None declared.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/cem.2014.73