Between 1907 and 1937, thirty-two states passed eugenical sterilization laws that allowed physicians in state institutions to operate on patients without their consent. The goal of those state sanctioned surgeries was to render the patients infertile, purportedly “for the health of the individual patient and the welfare of society.”1 Although the body of literature on the history of American eugenics has grown dramatically in the past three decades, there is to date no analysis of the lawmakers who sponsored the sterilization laws. This study is an effort to fill that gap. It contains a state-by-state listing of every legislator who introduced a sterilization law that ultimately passed, and it identifies those lawmakers by political party. It also reveals that political labels such as Republican/Democrat or “Progressive” are of little use in understanding who sponsored eugenic laws.

I focus on sterilization laws in this article because they represent one of the more infamous intrusions on individual liberties enacted in the name of eugenics. They are also relatively unique and easily identified, unlike the various kinds of “eugenic marriage laws” that required medical examinations before marriage or excluded some people from marriage because of their supposedly hereditary “defects.”Reference Wilson2 Similarly, I have not dealt with the so called “racial integrity” laws that prohibited interracial marriage. Those statutes require separate analysis, both because they were often passed before the formal eugenics movement began, and also because tracing changes in existing laws (rather than separate and new ones) requires a different type of analysis. Finally, I have not included attempts, successful or otherwise, to amend the sterilization statutes I have listed.

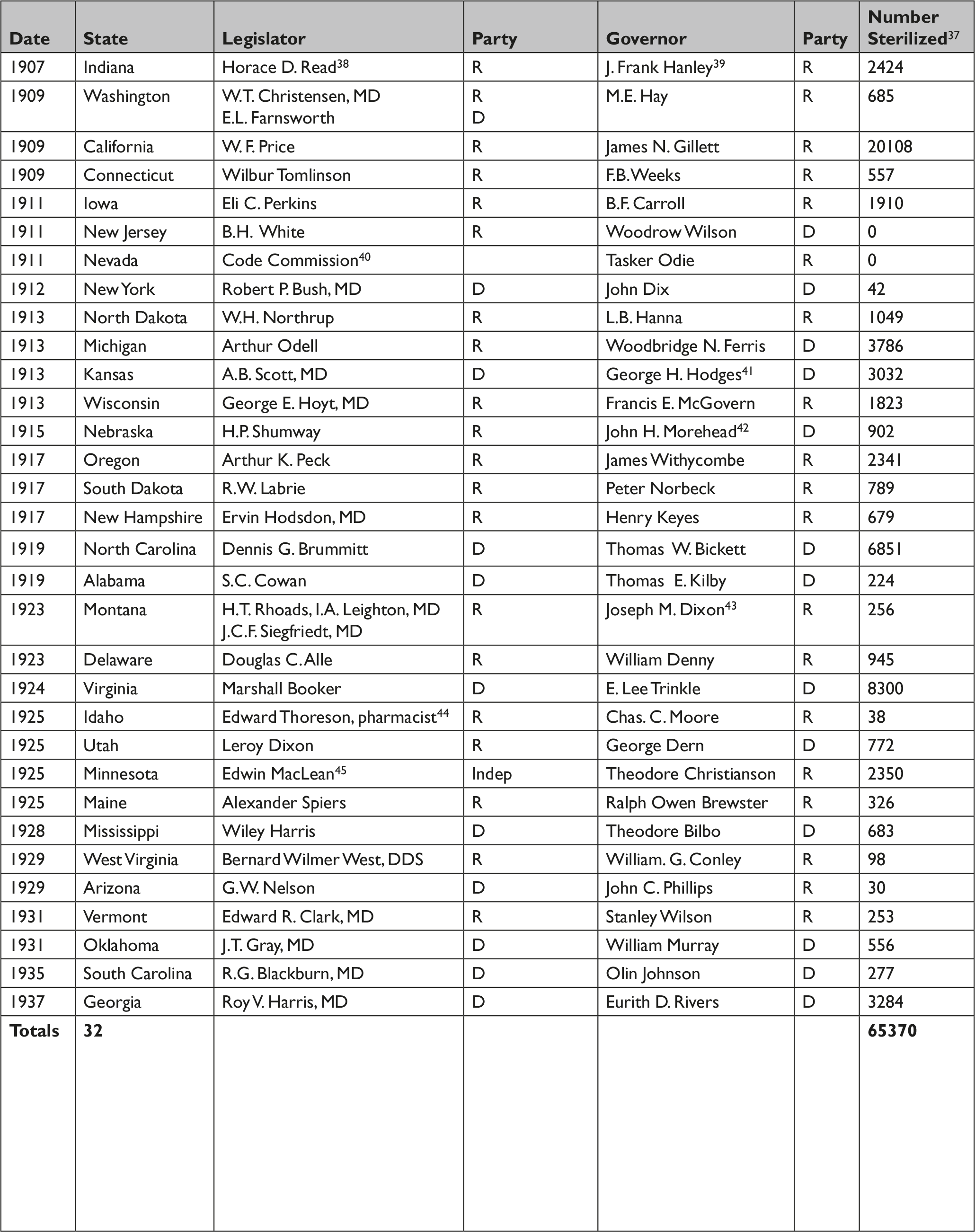

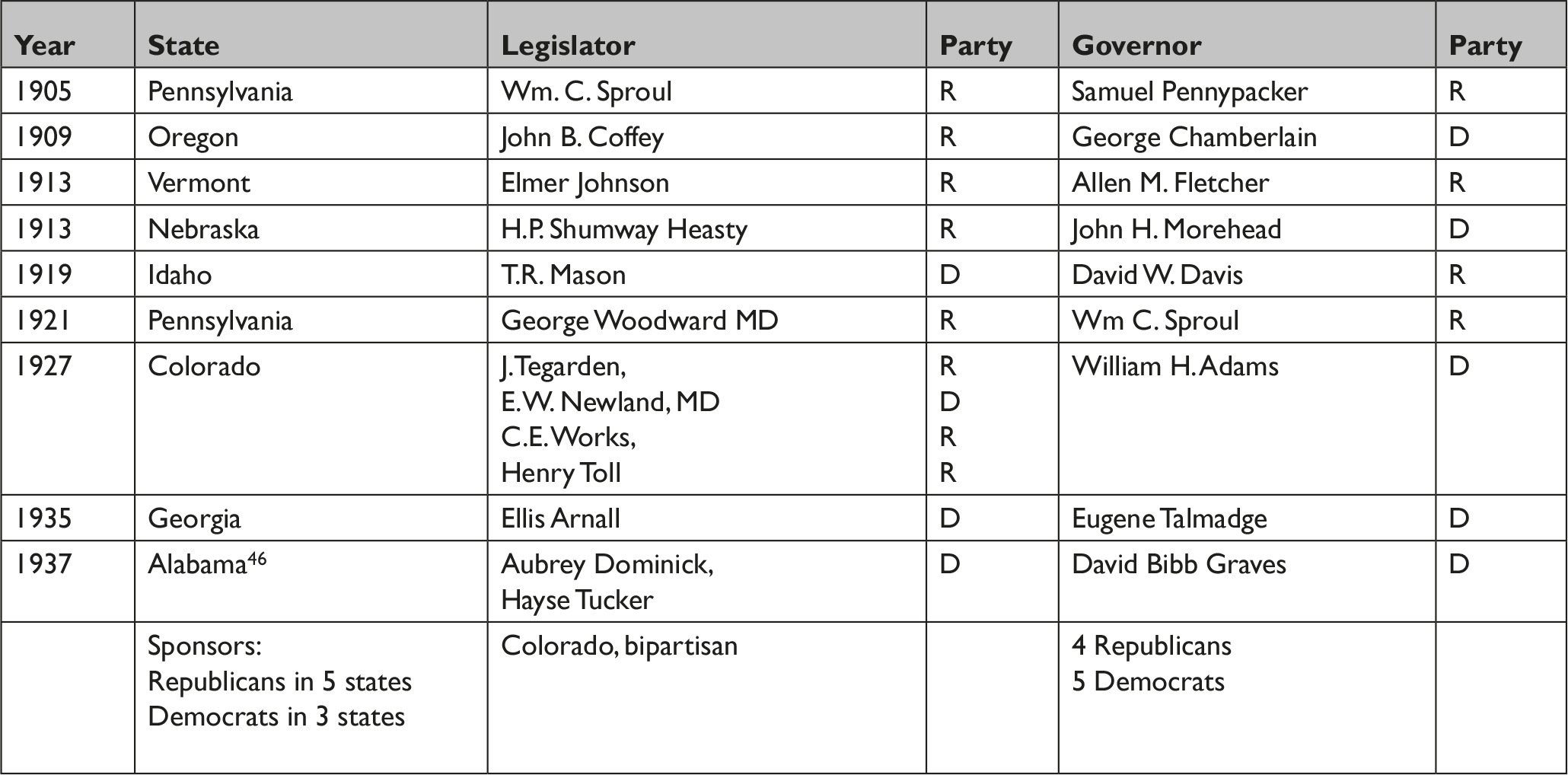

Table I includes the names of legislators designated as the primary sponsors of bills to authorize surgery in each state with a sterilization law, and the governors who signed those laws. I searched the annual Acts of Assembly for each state, determined from the legislative records who had presented the relevant bill, then identified the governor who had signed the bill into law. In some cases, secondary sources and contemporary newspapers also provided the necessary information. I then identified every state legislator and governor by political party and profession/vocation. Table II lists by state and party each governor who vetoed a sterilization bill.

Table I Sterilization Supporters: Legislators and Governors

Table II Vetoed Sterilization Bills

Were Eugenic Sterilization Bills Sponsored by Republicans or Democrats?

Identifying the political and ideological allegiances of individual advocates of eugenics can be helpful in understanding how eugenics became a major theme in American law in the first half of the 20th Century. But claiming that we can understand eugenic legal history as the product of a single party or advocates on one side of the political spectrum is incorrect.

Even when “eugenics” was word known in every household it was hardly the property of any political party. Rather than describing the laws passed in eugenics’ name as a product of partisan politics, this paper simply catalogues the legislators who championed sterilization laws and identifies the political party with which they identified.

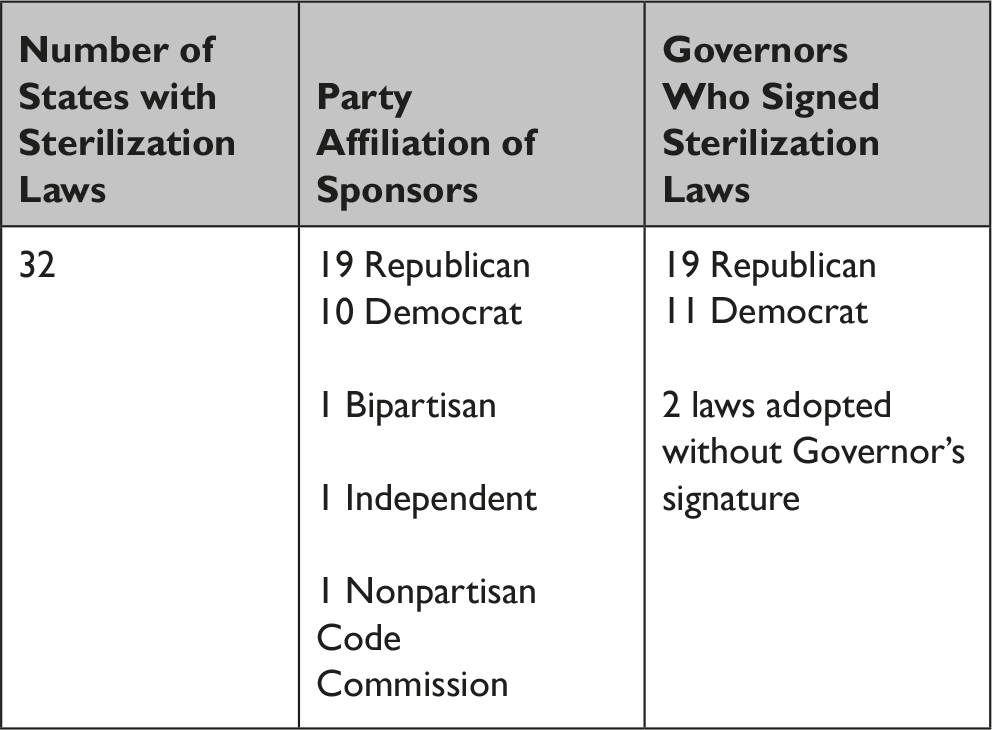

Summary Findings

Nineteen of the thirty-two states with sterilization laws were sponsored by Republican legislators alone, while ten states had only Democrats as sponsors. Washington had both Democratic and Republican sponsors, the Minnesota law was drafted by an Independent, and Nevada’s statute was presented by a nonpartisan Code Commission consisting of state Supreme Court Justices, with no named sponsors.

Governors who signed the sterilization laws were distributed similarly. There were nineteen Republicans Governors and eleven Democratic Governors whose signature made sterilization the law. In two states (Kansas, 1913 and Nebraska, 1915) legislators advanced bills that were passed but became law without a Governor’s signature. In Kansas the sponsoring legislator and the Governor were Democrats; in Nebraska the legislator and the Governor were Republicans.3 In at least six states (Washington, New Jersey, Michigan, Utah, Arizona, and Minnesota) there was bipartisan support for a sterilization law — a Governor of one party and sponsor(s) from another.

Box 1 Summary Findings

Governors who supported or opposed sterilization were also important. They sometimes signaled their support for a eugenical sterilization law in a campaign speech or inaugural address.

For example, Oregon Governor Oswald West (Democrat, 1913) announced his support for a sterilization law, saying:

We confine the vicious and irresponsible for a while, only to send them forth to blight the future by the creation of defective children that will grow into the criminal and the imbecile. Society is crying for protection, and this protection should be given. False modesty, in the past, has caused us to speak softly and to handle this subject with gloved hands. Recent disclosures have emphasized the fact that the time has come to speak aloud.4

James Withycombe (Republican, 1915) echoed those sentiments:

I am more and more convinced that the reproduction of the mentally unfit is absolutely wrong. Through our shortsighted inaction we are populating our State with imbeciles and criminals, insuring ever-increasing public expense and opening the way for disease, sorrow and tragedy for generations yet unborn … To mend this situation, I earnestly urge the passage of a sane Sterilization Act.5

Speaking in a similar vein, Vermont Governor Stanley Wilson (Republican, 1931) called for a sterilization law early in his term, saying:

I believe it is folly to keep erecting more buildings for our feeble-minded and insane and yet disregard ordinary business and social precautions. The Supervisors of the Insane in their biennial report recommend the enactment of a properly safeguarded sterilization law. You will do well to give this matter serious consideration.6

Others, like North Carolina Governor Thomas Walter Bickett (Democrat, 1919), provided their full-throated endorsement for a sterilization law after its passage:

In my opinion the most important and the most advanced step taken in the domain of health laws is the statute that gives authority to the medical staffs in our penal and charitable institutions to perform operations on inmates of those institutions that will make it impossible for incurable lunatics and imbeciles to “multiply and replenish the earth.” …Reference House7

Governors were also important in rejecting eugenical sterilization laws. Nine bills were passed by state legislatures, only to be vetoed by governors. In five of those states, Republican lawmakers sponsored the bills. They were met with vetoes by three Republican governors, and twice by Democrats. In the three states where Democratic legislators had sponsored successful bills, the veto came from one Republican and two Democratic governors. In Colorado, a bipartisan group of Republicans and Democrats sponsored a successful bill, but it was vetoed by a Democratic governor.

Veto messages were also revealing. In contrast to the champions of state sponsored surgery, Pennsylvania Governor Samuel Pennypacker vetoed what could have been the first law in the country to allow sterilization, in 1905.

It is plain that the safest and most effective method of preventing procreation would be to cut the heads off the inmates, and such authority is given by the bill to this staff of scientific experts … Scientists like all men whose experiences have been limited to one pursuit … sometimes need to be restrained. Men of high scientific attainments are prone … to lose sight of broad principles outside of their domain … To permit such an operation would be to inflict cruelty upon a helpless class … which the state has undertaken to protect.Reference Laughlin8

Colorado Governor William H. Adams (Democrat, 1927) listed his own motives for a veto, noting that it applied only to people who were wards of the state, and

The end sought to be reached by the legislation can be obtained by the exercise of careful supervision of the inmates without invoking the drastic and perhaps unconstitutional provisions of the act … any compulsory violation of the person of an individual is undesirable.9

Alabama Governor David Bibb Graves (Democrat, 1935) rejected a revised and expanded sterilization law, saying:

I am convinced that the social benefits expected to result from this bill are dependent largely upon theories, upon which the experts are far from agreement. The hoped for good results are not sure enough or great enough to compensate for the hazard to personal rights that would be involved in the execution of the provisions of the bill.10

But knowing the political party of any individual — Governors or legislator — would not help predict with any degree of certitude who would endorse eugenic sterilization. For example, among those who first opposed sterilization, Pennsylvania’s Samuel Pennypacker was a Republican. A generation later, Alabama’s David Bibb Graves issued the final veto as a Democrat. In Georgia, Governor Eugene Talmadge, a Democrat, vetoed a 1935 sterilization bill that was subsequently signed after the next legislative session in 1937 by Ellis Arnall, another Democrat.

Even more remarkably, Pennsylvania twice passed sterilization bills that were vetoed. In the first instance (1905), Republican state Senator William C. Sproul shepherded the bill through passage, only to have Republican Governor Samuel Pennypacker veto it. In 1921, state Senator George Woodward, a Republican, sponsored the bill but it was vetoed by the man who had introduced similar legislation sixteen years earlier; by then he had been elected Governor William C. Sproul, and was still a Republican.

Were Eugenic Sterilization Bills Sponsored by “Progressives?”

Since the 1960s, there has been a flood of scholarship and popular commentary on the history of eugenics in America. Some of that commentary has attempted to link eugenic enactments with political movements like “Progressivism.” But scholars have understood for some time that attempting to explain the passage of eugenic legislation by claiming that one ill-defined ideological faction alone supported such laws did little to advance our understanding of the legislative process. For example, Donald Pickens’ 1968 book Eugenics and the Progressives was an early attempt to analyze the impact of progressive ideology on eugenic activism. Pickens argued that “eugenic policy was basically conservative and the scientists and politicians who adhered to it were likewise conservative, despite the fact that they called themselves progressive reformers.”Reference Pickens11 One reviewer of Pickens’ book stated: “To put it another way, according to Pickens, “conservatives” supported eugenics as a means of protecting the status quo of power, money, and social hierarchy.”Reference Cowan12

Yet even in the first decades of the 20th Century, “progressivism” was a fluid concept with shifting boundaries. Unfortunately, Pickens never defined what another reviewer termed the “inchoate movement toward political reform” characterized as “progressivism,” and “lumped together under that term ideas such as Darwinism, naturalism, revolution, class struggle, industrialization and the multitude of urban problems.” Said the reviewer, “that list of words seems too great a social and political burden for one term to bear.”Reference Dunn13

Political pundits routinely identify eugenics as an entirely “progressive” enterprise,14 while in contrast to Pickens, other scholars have missed the mark in the other direction, labeling eugenics as a “conservative” impulse.Reference McCloskey15

Other scholars of eugenics have emphasized the flexibility in the progressive label, noting that “progressivism attracted followers from all parts of the political spectrum, …[and] eugenicists ranged from conservative elitists such as [Charles] Davenport through liberals such as [David Starr] Jordan to such radical leftists as geneticist Hermann J. Muller.”Reference Larson16 The point is easily underlined by recalling that the first six presidents of the twentieth century — Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, Woodrow Wilson, Warren Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover — each supported some eugenic policies.Reference Lombardo17 Similarly, Supreme Court Justices known as “anti-progressives,” who regularly struck down “progressive” labor laws also voted to validate statist measures such as Virginia’s sterilization law in Buck v. Bell. Reference Hovenkamp18 Recently an entire book took on the “progressive” pedigree of much eugenic advocacy conceded that using “progressive” as a one-dimensional label was likely to force a writer to abandon nuance.Reference Leonard19

In this study, I list several legislators who identified themselves as Republican or Democrat, but simultaneously claimed a “progressive” label. Among Governors who vetoed sterilization laws, both Democrat Bibb Graves and Republican Samuel Pennypacker have been described as “progressives,”Reference Sicius20 while in Georgia, Democrat Eugene Talmadge vetoed a sterilization bill precisely because he thought it was too “progressive.”21 In the two states where sterilization laws became law without a governor’s signature (Kansas and Nebraska) both a Democrat and a Republican were governors, and both were also widely identified as “progressives.”

Doctors

Although nearly twice as many Republicans as Democrats sponsored sterilization laws, and Republican governors who signed the bills outnumbered Democrats in roughly the same proportion, it is easy to make too much of these political labels. With good reason, much of the existing state level scholarship on eugenic sterilization laws has focused on people whose lobbying efforts were critical to the passage of sterilization laws, rather than the legislators themselves. The lawmakers often took their cues from constituents for whom these laws were much more important. The period when sterilization laws were first passed (1907-1937) coincided with the growth of organized medicine with heightened emphasis on formal medical educationReference Ludmerer22 and the growing attention to credentialed expertise was simultaneously one of the hallmarks of “progressive” thought, and an emphasis also embraced by leaders in eugenics.23

Among the most noteworthy advocates of sterilization were physicians such as Harry Sharp in Indiana, the first state with a law, or Frederick Winslow Hatch in California, the state with the most operations.Reference Stern and Lombardo24 Drs. Albert Priddy and Joseph DeJarnette of Virginia played roles as eugenic leaders who not only advanced an important sterilization law, but also orchestrated a Supreme Court case to validate that law, which was then deployed to sterilize the second highest total of patient of any state.Reference Lombardo25 Bethenia Owens-Adair of Oregon,Reference Largent26 Charles Fremont Dight of Minnesota,Reference Holtan27 William Partlow of Alabama28 and Oklahoma’s Louis Henry RitzhauptReference Nourse29 were other prominent physicians whose advocacy in favor of sterilization laws did much to guarantee their passage. Other physicians like Harry Perkins of Vermont,Reference Gallagher30 William Allen of North Carolina,Reference Begos31 and Victor Vaughn of MichiganReference Vaughn and Aldrich32 filled the ranks of sterilization advocates, too numerous to name individually.

Given the indeterminacy of political party labels, and the myriad meanings that people assigned to “eugenics” during the thirty years that sterilization bills became law in the states, it is of little value to claim that any one party, political movement or occupational group can be credited, or blamed, for the success of eugenic sterilization laws.

Like pioneering 19th Century surgeons Albert Ochsner Reference Reilly33 and J. Ewing Mears,Reference Lombardo34 who developed the surgical technologies of vasectomy and crusaded for the surgical intervention as a tool of eugenics, physicians were among the most fervid supporters of eugenic laws.

Given the widespread advocacy for sterilization laws on the part of physicians, it should not surprise us that one of the most telling descriptors among the legislative sponsors of sterilization laws was not political party, but professional background. At least twelve different doctors sponsored laws in eleven different states (Montana had two different physicians as legislative sponsors), while two other states relied upon other health care providers (a dentist, West Virginia, and a pharmacist, Idaho) and Connecticut’s 1909 law was sponsored by an undertaker.35 Almost half of the bills that eventually passed originated with a legislator with professional training and/or experience in a health-related occupation.36 There were also at least four sponsors who identified as lawyers and an equal number of sponsors listed as farmers, with a smattering of businessmen, bankers and others of unidentified occupation.

Conclusion

This paper challenges the assertions of both scholarly commentators and media pundits who may too simplistically attempt to corral the range of interests and the goals of all things eugenic into political or ideological categories that have changed dramatically over time. It is even more problematic to assume that party names or political labels such as “progressive,” that have been in use for over a century, have maintained a static ideological significance.

Politicians of both major political parties sponsored and endorsed eugenic sterilization statutes during the three decades (1907-1937) in which thirty-two states adopted those laws. There were approximately twice as many Republicans than Democrats among legislative sponsors and a few more Republican governors who signed sterilization bills into law. Legislators with some kind of medical occupation accounted for almost half of all the successful bills for sterilization. Although physicians were involved in the passage of many sterilization laws, even more made their way into the statute books without the need for medical advocates among lawmakers.

Given the indeterminacy of political party labels, and the myriad meanings that people assigned to “eugenics” during the thirty years that sterilization bills became law in the states, it is of little value to claim that any one party, political movement or occupational group can be credited, or blamed, for the success of eugenic sterilization laws.

Note

The author has no conflicts of intereat to disclose.