Words are part of action and they are equivalents to actions.

The central problem of linguistic pragmatics and the anthropology of language is to understand the relation between speaking and doing, between language and action. Since Austin (Reference Austin1962) it has been widely appreciated that in speaking, persons are inevitably understood to be doing things, yet, somewhat surprisingly, a comprehensive account of just how action is accomplished through the use of language (and other forms of conduct) in interaction has been slow to develop. In this chapter we begin our sketch of an approach to this problem, by pointing to some of the materials that are relevant to such an account, some of the questions that must be addressed, and some of the central conceptual problems that require consideration.

If we are going to understand what human social action is, we must first acknowledge (1) that action is semiotic, i.e., that its formal composition is crucial to its function, because that formal composition is what leads to its ascription by others; (2) that action is strongly contextualized, i.e., that the shared cultural and personal background of interactants can determine, guide, and constrain the formation and ascription of an action; and (3) that action is enchronic, i.e., that it is a product of the norm-guided sequential framework of move and counter-move that characterizes human interaction. In other words, if we are going to understand action, composition matters, context matters, and position matters. We begin with an example that illustrates these three indispensable features of action in interaction.

Consider the following exchange from a small community of people in the Kri-speaking village of Mrkaa in Laos (300 km due east of Vientiane, just inside the Laos-Vietnam border). This recording is a representative sample of the sort of everyday human social reality that we want to explore in this book. Figure 1.1 is from a scene recorded on video on a humid morning in August 2006.

Figure 1.1 Screenshot from video recording of Kri speakers in Mrkaa Village, Laos, 8 August 2006 (060808d-0607).

The participants are sitting on the front verandah of the house of the woman named Phừà, the older woman who is sitting at the rightmost of frame. Here are the people in the frame, going from left to right of the image:

Sùàj = older woman in foreground, leftmost in image, with headscarf

Nùàntaa = teenage girl in doorway with her hand raised to her mouth

Mnee = young girl with short hair, hunched in doorway

Phiiw = middle-aged woman with black shirt near centre of image (Nùàntaa’s mother’s older sister)

Thìn = young mother in background

Phừà = older woman at right of image with headscarf (Nùàntaa’s mother’s mother)

The people in Figure 1.1 are speakers of Kri, a Vietic language which is spoken by a total of about 300 upland shifting agriculturalists in the forested vicinity of Mrkaa, a village in Nakai District, Khammouane Province, Laos (Enfield and Diffloth Reference Enfield and Diffloth2009). The time of recording is around 9 o’clock in the morning. The women in Figure 1.1 are just chatting. Some are sitting and doing nothing, others are preparing bamboo strips for basketry.

As the transcription in (1) below shows, at this point in the conversation the two older women, Sùàj and Phừà, are talking about people in the village who have recently acquired video CD players. They are voicing their opinions as to whose CD player is better, and whether they prefer black and white or colour. Our focus of interest for the purposes of our discussion of action is, however, not this trajectory of the conversation but the one that is started in line 13 by the teenage girl Nùàntaa (NT), who sets out to procure some ‘leaf’, that is, a ‘leaf’ of corncob husk, for rolling a cigarette. A few moments before this sequence began, Nùàntaa had asked for something to smoke, and was handed some tobacco by Sùàj.

(1) 060808d-06.23-06.50

01 (0.4) 02 Phừà: qaa tàà nờờ lêêq sd- sii ct.famil dem.dist prt take C- colour It was them who got a C- colour (CD set). 03 (1.0) 04 Phừà: sdii sii CD colour A colour CD set. 05 (1.0) 06 Phừà: teeq kooq prak hanq teeq dêêh lêêq 1sg have money 3sg 1sg neg take (If) I had money I (would) not take 07 qaa sdii (.) khaaw dam naaq hes CD white black dem.ext um a black and white CD set. 08 (2.7) 09 Sùàj: khaaw dam ci qalêêngq white black pred look (With) a black and white (CD set, one can) see 10 môôc lùùngq haar lùùngq= one story two story one or two stories (only). 11 Phừà: =hak longq haj paj- but clf nice cop But the ones that are nice are- 12 Phừà: longq [tak ] paj haj clf correct cop nice The ones that are ‘correct’ are nice. 13 NT: [naaj] mez Aunty 14 ((0.7; Mnee turns gaze to Phiiw; Phiiw does not gaze to Nùàntaa)) 15 NT: piin sulaaq laa give leaf prt Please pass some leaf. 16 ((1.0; Mnee keeps gaze on Phiiw; Phiiw does not gaze to Nùàntaa)) 17 NT: naaj= ((‘insistent’ prosody)) mez Aunty! 18 Sùàj: =pii qaa like hes Like um- 19 (0.5) ((Phiiw and Phừà both turn their gaze to Nùàntaa)) 20 NT: piin sulaaq give leaf Pass some leaf. 21 Phừà: sulaaq quu kuloong lêêh, leaf loc inside dem.up The leaf is inside up there, 22 sulaaq, quu khraa seeh leaf loc store dem.across the leaf, in the storeroom. 23 (0.7) 24 Phừà: môôc cariit hanq one backpack 3sg (There’s) a (whole) backpack. 25 (5.0) ((Nùàntaa walks inside in the direction of the storeroom))

The course of action that Nùàntaa engages in here, beginning in line 13, is an instance of one of the most fundamental social tasks that people perform: namely, to elicit the cooperation of social associates in pursuing one’s goals (see Rossi Reference Rossi, Drew and Couper-Kuhlen2014; and Chapter 3 below). It presupposes that others will cooperate, that they will be willing to help an individual pursue their unilateral goals. This is the most basic manifestation of the human cooperative instinct (Enfield 2014), which is not present in anything like the same way, or to anything like the same degree, in other species (Tomasello Reference Tomasello2008). In this case, Nùàntaa is indeed given assistance in reaching her goal – here not by being given the leaf she asks for, but by being told where she can find some.

Now that we have introduced this bit of data drawn from everyday human social life, how, then, are we to approach an analysis of the actions being performed by the people involved?

Social Action Is Semiotic

It is obvious, but still worth saying, that an adequate account of how social actions work must be a semiotic one in that it must work entirely in terms of the available perceptible data. This follows from a no telepathy assumption, as Hutchins and Hazlehurst (Reference Hutchins, Hazlehurst and Goody1995) term it. If actions can be achieved at all, it must be by means of what is publicly available. More specifically, this requires that we acknowledge the inherently semiotic mode of causation that is involved in social action. When we talk about action here, we are not talking about instrumental actions in which results come about from natural causes. In the example that we are exploring, the girl Nùàntaa launches a course of behaviour that eventually results in her getting hold of the cornhusk that she desired. For a semiotic account of the social actions involved, we need to know how Nùàntaa’s behaviour – mostly constituted in this example by acts of vocalization – could have been interpreted by those present, such that it came to have the results it had (namely, that she quickly came into possession of the leaf she was after).

A first, very basic, issue has to do with units. It is commonplace and perhaps commonsensical to assume that a single utterance performs a single action. Whether it is made explicit or not, this is the view of the speech act approach. If something is a promise, for example, it cannot at the same time be, say, a request. However, there are obvious problems with this. For a start, the very notion of an utterance is insufficiently precise. Rather, we have to begin by, at least, distinguishing utterances from the discrete units that constitute them. In the conversation analytic tradition, we can distinguish a turn-at-talk (often roughly equivalent to ‘utterance’ in other approaches) from the turn-constructional units (or TCUs) of which it is composed (roughly equivalent to ‘linguistic item’ in other approaches, thus not only words but other meaningful units, some being smaller than a word, some larger; see Sacks et al. Reference Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson1974; Langacker Reference Langacker1987). A turn may be composed of one, two, or more TCUs, and each TCU may accomplish some action. Consider these lines from our example:

(2) 060808d-06.23-06.50 (extract)

13 NT: [naaj] mez Aunty 14 ((0.7; Mnee turns gaze to Phiiw; Phiiw does not gaze to Nùàntaa)) 15 NT: piin sulaaq laa give leaf prt Please pass some leaf.

The utterance translated as ‘Aunty, please pass some leaf’ is composed of two TCUs. In the first TCU (line 13) the speaker uses a kin term, naaj ‘(classificatory) mother’s elder sister’, to summon one of the co-participants (Schegloff Reference Schegloff1968). Notice that this TCU projects more talk to come and with it the speaker obligates herself to produce additional talk directed at the person so addressed (thus a common response to a summons like this might be What? or Hold on). One cannot summon another person without then addressing them further once their attention has been secured. In the second TCU of this turn, the speaker produces what can, retrospectively, be seen as the reason for the summons: a ‘request’ that Aunty pass some leaf (this move to be discussed further, below).

This TCU/turn account in which each TCU is understood (by analysts and by the participants) to accomplish a discrete action appears to work reasonably well for the present case, but there are complications. First, there are cases in which a series of TCUs together constitutes an action that is more than the sum of its parts. For instance, a series of TCUs that describe a trouble (e.g., I’ve had a long day at work, and there’s no beer in the fridge) may together constitute a complaint (This is bad, there should be some beer) or a request (Could someone get some beer?; see, e.g., Pomerantz and Heritage Reference Pomerantz, Heritage, Sidnell and Stivers2012). And there are cases in which a single TCU accomplishes multiple actions. Indeed, there are several senses in which this is the case. There is the telescopic sense, whereby a given utterance such as What is the deal? constitutes both a question (which makes an answer relevant next) and an accusation (which makes a defence, justification or excuse relevant next), or That’s a nice shirt you’re wearing is both an assessment (saying something simply about my evaluation of the shirt) and a compliment (saying something good about you). It seems obvious in this case that ‘assessment’ and ‘compliment’ are not two different things but two ways of construing or focusing on a single thing. Similarly, we might look at a labrador and ask whether it is a ‘dog’, an ‘animal’, or a ‘pet’. It is of course all of these, and none is more appropriate than the other in any absolute sense.

There is also the possibility that an utterance is ambiguous as to the action it performs, in the sense that an utterance might have two possible action readings but cannot have both at the same time. For example, consider the utterance Well, I guess I’ll see you sometime said during the closing phase of a telephone call. What is the speaker doing by saying this? It might constitute a guess at some possible future event. Or it could be a complaint about the recipient’s failure to make herself available.

And, finally, there is the idea that different actions can be made in parallel, by means of different elements of a single utterance: for example, a given word or phrase, embedded in an utterance meant to accomplish one action, might accomplish another simultaneous action. In one case, a mother has rejected her daughter’s request to work in the store, and she explains this rejection by saying People just don’t want children waiting on them. With the use of the word ‘children’ – implying ‘you are a child’ – she is effectively belittling her daughter in the process of giving an explanation (see discussion of this case in Chapter 4, below).

Much of this follows directly from the semiotic account we are proposing. Specifically, although TCUs may be typically treated as ‘single-action-packages’, they are in fact outputs/inputs of the turn-taking system (Sacks, Schegloff, and Jefferson Reference Sacks, Schegloff and Jefferson1974) and only contingently linked to the production of action per se. Participants, then, apparently work with a basic heuristic which proposes that one TCU equals one action, but the inference this generates is easily defeated in interaction. The more general point, following directly from the semiotic assumptions of our approach, is that TCUs – and for that matter talk in general along with any other conduct – is nothing more and nothing less than a set of signs that a recipient uses as a basis for inference about what a speaker’s goal is in producing the utterance (or, essentially, what the speaker wants to happen as a result of producing the utterance).

Whatever a speaker is understood to be doing is always an inference or guess derived from the perceptible data available. That includes talk, but it includes much else besides. In the case of language, things get complicated (or look complicated to analysts) because the specifically linguistic constituents of conduct appear to allow for a level of explicitness that is unlike anything else. It is as though a speaker can merely announce or describe what they are doing. Moreover, such formulations may be produced at various levels of remove from the conduct they are intended to describe. One can thus distinguish between a reflexive metapragmatic formulation (I bet you he’ll run for mayor) and a reportive metapragmatic formulation (He bet me that he would run for mayor), and within the latter one can distinguish between distal (as above) and proximate versions (Oh no I’m serious, I meant to put a wager on it when I said I’ll bet you!), etc. One can already begin to see, however, a major disconnect between action-in-vivo and explicit action formulations using language. Thus, when someone says I bet you he’ll run for mayor, thereby apparently formulating what they are doing in saying what they are saying, they are almost certainly not betting (in the sense of making a wager) but rather predicting a future state of events.

All of this leads us to the conclusion – originally developed most cogently within conversation analysis (see Schegloff and Sacks Reference Schegloff and Sacks1973 and Schegloff Reference Schegloff1993) – that any understanding of what some bit of talk is doing, whether the analyst’s or the co-participant’s, must take account of both its ‘composition’ and its ‘position’. To take one example, the word well can function in different ways depending both on exactly how it is pronounced and on where in an utterance it is placed: thus, using a lengthened We::ll at the beginning of a response to a wh-question routinely indicates that something other than a straightforward answer is coming (see Schegloff and Lerner Reference Schegloff and Lerner2009); by contrast, a well produced at the end of a stretch of talk on a topic during a telephone call may initiate closing (Schegloff and Sacks Reference Schegloff and Sacks1973).

Social Action Is Always Contextualized

We judge an action according to its background within human life, and this background is not monochrome, but we might picture it as a very complicated filigree pattern, which, to be sure, we can’t copy, but which we can recognize from the general impression it makes. The background is the bustle of life. And our concept points to something within this bustle.

Actions are accomplished against a background of presupposition – what is commonly termed context. There are two basic senses in which this is the case. First, there is context in the sense of an historically constituted linguistic code and set of cultural understandings. Second, there is context in the sense of what someone just said, how the speaker and recipient are related to one another, and what is happening in the immediately available perceptual environment and so on. Context in the first sense is essentially omnirelevant: that /kæt/ means a carnivorous animal often kept as a house pet is a part of the backdrop of any interaction in English. Context in the second sense is more dynamic. Aspects of context can be activated and oriented to by the participants within the unfolding course of interaction (Sidnell Reference Sidnell, Stokoe and Speer2010b; Enfield Reference Enfield2013), alternatively they can be disattended. Thus, these two aspects of context are fundamentally intertwined, since it is the very cultural understandings in the first sense of context that are activated and made relevant in the second sense of context.

In recent work, attempts have been made to give a systematic account of the way participants assess a given utterance against the backdrop of assumptions in order to understand what action it is meant to accomplish. For instance, Heritage (Reference Heritage2012) suggests that a recipient will often draw on assumptions about who knows what (epistemic status) in deciding whether a given utterance is doing an action of ‘asking’ or one of ‘telling’. For instance, a speaker who produces a declaratively formatted utterance describing something about the recipient (e.g., You’re tired) has conveyed a relatively certain epistemic stance that runs counter to the usual assumptions of epistemic status (i.e., that people know more about how they themselves feel than others do) and thus is likely to be heard as asking rather than telling. Heritage (Reference Heritage2012:1) proposes: ‘Insofar as asserting or requesting information is a fundamental underlying feature of many classes of social action, consideration of the (relative) epistemic statuses of the speaker and hearer are a fundamental and unavoidable element in the construction of social action.’ Roughly speaking, Heritage shows that a recipient’s assumptions about what the speaker does or does not know are decisive in determining whether a declaratively formatted utterance is heard to be telling or asking (see also Sidnell Reference Sidnell2012b). The idea here, then, is that a given utterance conveys its speaker’s epistemic stance and that this is understood against the backdrop of assumptions that constitute epistemic status.

Might such insights be generalized to other domains of action in interaction? For instance, one could suppose that in the case of cooperative action sequences a speaker may convey a deontic stance that will be measured against the relatively stable, enduring assumptions of deontic status. Deontic stance, within this view, names the various ways of coding entitlement and authority in the utterance itself (compare Get out! with Would you mind stepping outside for a minute?). Deontic status has to do with the relatively perduring assumptions about who is entitled or obligated to do what.

Incongruity between stance and status in this domain has similar inferential consequences as does incongruity in the domain of epistemics. For instance, when a recipient who has just received some surprising bit of news says Shut up or Get out of here, they are not understood to be issuing a directive but rather conveying surprise or interest (Heritage Reference Heritage2012:570). Inferences are also possible from utterances which adopt a ‘D-minus’ stance, that is, which are phrased as if the speaker has diminished entitlement to make the action at hand. For example, a parent can convey great seriousness and an unwillingness to negotiate by saying to a child Will you please stop talking, as if it were a polite request, or I’m asking you to finish your dinner, as if it were a formal statement.

In our example we can see that Nùàntaa’s turn, piin sulaaq laa ‘Please pass some leaf’, in line 15, adopts a deontic stance congruent with the assumptions of deontic status: namely, as one of the youngest people on the scene, she is ‘below’ her addressees in kinship terms, and thus in terms of her entitlements to impose on others with requests such as this one. The summons by means of a kin term in line 13 makes this explicit, marking and thereby activating this aspect of context.

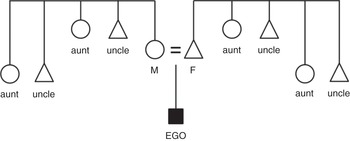

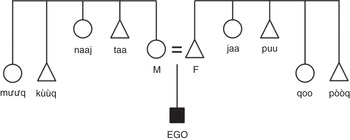

Let us, now, look into our example more closely, to illustrate the necessity of drawing upon the numerous systemic backgrounds against which the participants in this little scene can make sense of it. We start with line 13, in which Nùàntaa launches her course of action with the goal to acquire some leaf for rolling tobacco. The utterance consists of a single word: naaj. The only direct translation into English of this word would be ‘aunt’, but while these words have some overlap in denotational range they are not equivalent. The Kri system of kinship terminology differs from that of English in a range of ways.Footnote 1 For one thing, the system makes a great number of distinctions, segmenting the kinship space far more finely than English: compare Figure 1.2 and Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.2 English terms for siblings of parents (2 terms, distinguished only by sex of referent); relative height of members of same generation represents relative age (not captured in the meanings of the English terms).

Figure 1.3 Kri terms for siblings of parents (8 terms, distinguished by sex of referent and sex of parent and age of referent relative to parent).

The action that is done in line 13 is done by means of a single lexical unit, the kin term naaj ‘mother’s older sister’. What action is Nùàntaa performing with this one-word utterance? A basic characterization would be to say it is a summons. It is a first move in opening up the channel for interaction. We do this when we walk into a house and call out Hello? in order to open up a possible interaction (Clark Reference Clark1996). Or indeed, and as Schegloff (Reference Schegloff1968) argues, the ringing of a telephone is a summons as well, and serves a similar function to Nùàntaa’s utterance here. But if we compare Nùàntaa’s kin-term utterance with the kind of summons that a telephone ring can perform, we see that they have different affordances. One thing that Nùàntaa’s specific form of summons does here is to make explicit her kin relation (and thus her social relation) to the addressed party. Clearly other ways of doing the summons were possible (e.g., she might have used the recipient’s name) and doing it in this way, rather than another, has a number of collateral effects, as we term them. As we explain in Chapter 4, the selection of a linguistic structure as the means to some end (e.g., summoning a participant by use of a kin term) will inevitably have a range of consequences for which that means was not necessarily selected (e.g., characterizing the relationship between speaker and recipient in terms of kinship rather than in some other available terms).

Chapter 4 compares collateral effects across different linguistic systems, but we can note in passing here that while both Kri naaj and English aunt characterize the relation between speaker and recipient, the way they do this is different in the two languages. Specifically, while ‘aunt’ merely conveys that the recipient is the speaker’s parent’s sister, ‘naaj’ indicates that the recipient is mother’s older sister (and thus a member of the speaker’s matrilineage, etc.). So some collateral effects are internal to a specific linguistic system. For instance, had Nùàntaa issued her summons by saying Hey! or some such rather than ‘naaj’, the effects would have been quite different though the action would still be reasonably characterized as summoning (although with some ambiguity as to who she was in fact summoning). Other collateral effects are external to a linguistic system and can only be seen through a comparison of the different semiotic resources they make available for the accomplishment of action.

So there are collateral effects of doing the summons in this way. And the particular effects that arise are not merely incidental. Kri speakers seem especially concerned with kin relations. So with line 13, which is just the opening of Nùàntaa’s course of action, and which in itself is purely in the service of that course of action, she has used a single term from a closed class of kin terms to make a summons. The utterance’s full action import cannot be understood without the full systemic context of kinship and kin terminology.

Once Nùàntaa has used the term naaj to single out Phiiw as her addressee and thereby summon Phiiw’s attention, she then produces a next move in her course of action, here what could reasonably be called a request. She does this by naming the action she wants Phiiw to do (‘pass’) and identifying the thing she wants (‘leaf’). This utterance, shown in (3), introduces further aspects of the linguistic system that provides Kri speakers with their resources for social action:

(3) 060808d-06.23-06.50 (extract)

15 NT: piin sulaaq laa pass leaf prt Please pass some leaf.

The turn has several properties worth mentioning in terms of its design or composition:

1. No explicit person reference is used.

2. None of the available alternate constructions are used; e.g., she could have said ‘Where can I get some leaf?’

3. The verb choice piin ‘to pass, present’ is chosen instead of the more general word cơơn ‘pass’.

4. The ‘polite’, ‘softening’ particle laa is used.

The translation here is something like ‘Please pass some leaf’, and so it seems reasonable to describe it as a request (but see Chapter 4 on the problem of labelling/describing actions, and Chapter 3 on joint action and cooperation specifically). Note, however, that the utterance is not explicitly marked as a request. There is no explicit marking of imperative mood, as, for example, is done in English with the infinitive verb form, nor is the omission of reference to the subject of the verb associated with imperative force in the Kri language. Thus, while it is seemingly clear to the participants that Nùàntaa is asking for something, it is done in a semantically general way. The phrase piin sulaaq could, in another context, mean ‘(He) gave (me) some leaf’, or ‘(I will) give (them) some leaf’, among other interpretations. One thing that Nùàntaa does with this format is to leave the interpretation of who is to give leaf to whom entirely dependent on the context. Context is more than strong enough to support the action she is launching here: it is part of the participants’ common knowledge that Nùàntaa has, moments before, procured some tobacco, and further, that she has selected Phiiw as the addressee of this utterance.

Another feature of this utterance that cannot be understood without reference to the linguistic system as background context is its value with reference to other ways in which she could have produced the utterance. One way, for example, is as a question, for instance Where is some leaf? Then there are the specific lexical choices. The thing she is requesting is named by its normal, everyday label sulaaq, meaning ‘leaf’. She doesn’t need to specify ‘corncob husk for smoking’. And of relevance to the fact that her action is a request, issued to a superior, is the choice of the verb piin. This verb means ‘pass’ or ‘hand over possession of’, but it is not the everyday word for ‘give’ in the mundane sense of handing something over, such as when someone passes someone a knife, a glass of water, or a rag to wipe their hands with. The verb piin is more marked, both semantically (by being more specific) and pragmatically (by being used less often and in a narrower range of contexts). And finally, the marker laa belongs in a closed class of sentence-final particles, well known in the Southeast Asia region for their importance in marking subtle distinctions in ‘sentence type’ or speech act function. Notice that the laa is omitted when Nùàntaa repeats the request after it has apparently not been heard by Phiiw.

Through this simple example, we can see an important sense then in which social relationships are constituted through action (see Enfield Reference Enfield2013 and references cited therein). Some of it this is obvious, such as, for instance, the ways in which people address each other using kin terms. But many of the ways in which social relations are constituted are less explicit. Following Goffman, we could say that social relations are ‘given off’ here by the simple fact that the girl is evidently entitled to ask and the recipient is apparently obligated to provide (see Rosaldo Reference Rosaldo1982; Goodwin Reference Goodwin1990). We can note that the addition of laa (a polite particle, appropriately used in addressing people who are senior or otherwise deserving of respect) orients to just this relation of entitlement/obligation.

One can easily see the implications of this for linguistics. Specifically, for all of grammar, there is a basic sense in which you cannot understand it unless you understand how it is used in interaction. Elicitation simply does not provide an adequate account of grammatical meaning (elicitation being better suited to the study of grammaticality judgements). Beyond that, though, there are parts of the grammar whose meanings are simply not elicitable.

Now let us consider further the system context as it relates to lines 21–22, the utterance in which Phừà provides the solution to Nùàntaa’s problem. Here, Phừà makes good use of the system of spatial demonstratives. Phừà tells Nùàntaa where the leaf is, giving quite specific spatial coordinates relative to where the interlocutors are presently sitting:

(4) 060808d (extract)

21 Phừà: sulaaq quu kuloong lêêh, leaf loc inside dem.up The leaf is inside up there, 22 sulaaq, quu khraa seeh leaf loc store dem.across the leaf, in the storeroom.

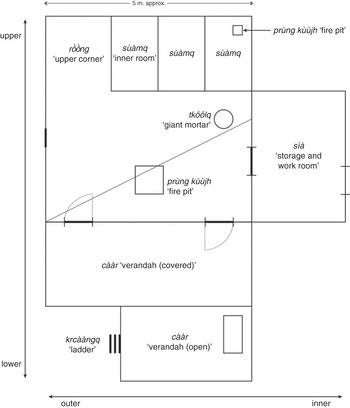

The Kri language has a five-term system of exophoric demonstratives, which is partly built on the Kri speakers’ deep-seated orientation to a riverine up-down environment:

(5)

a. nìì general (‘this’, proximal) b. naaq external (‘that’, distal) c. seeh across (‘yon’, far distal) d. cồồh external, down below e. lêêh external, up above

This system for spatial orientation, with its ‘up’, ‘down’, and ‘across’ terms, is used with reference not only to outdoor space but also to local ‘table top’ space (Levinson and Wilkins Reference Levinson and Wilkins2006). As outlined in Enfield (Reference Enfield2013: Chapter 11), the up-down and across axes are mapped onto the Kri traditional house floor plan, as shown in Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4 Kri traditional house floor plan.

Within this activity of direction-giving, the Kri demonstratives invoke the house structure and its semiotics, relating to the physical environment (see Enfield Reference Enfield2013). For present purposes, we are interested in the action that is being done through this utterance. It is unequivocally an action of ‘telling’. More specifically, it is an instruction that helps the recipient to satisfy the goal she has expressed in her turn at line 15 and again at line 20. But notice that this turn could be understood in other ways simultaneously. For instance, Nùàntaa may hear in this a reprimand for asking: ‘Don’t expect to be given it, go and get it yourself’. Or she may hear this as an expression of permission, essentially equivalent to saying ‘You may have some of our household leaf’.

We noted earlier that Nùàntaa’s request could have been formulated as a ‘Where?’ question, but it wasn’t. Now see that Phừà’s utterance in line 21 responds to the question precisely as if it had in fact been a ‘Where?’ question. Phừà does not respond by giving Nùàntaa some leaf, rather she tells her where some leaf can be found, implying where Nùàntaa can get some herself, and in doing this she addresses Nùàntaa’s goal. And note that this further orients to the social relations at hand. Simply telling Nùàntaa where she can get some leaf presumes that she will indeed go and get it herself; were the asker a guest, it is likely that Phiiw would have got up, or got someone else to fetch the leaf.

We can take this analysis one step further to propose that at the heart of this little scene is an issue of propriety. Thus, although the request is done as ‘pass’ (which focuses on possession transfer), it is treated as ‘where?’ The response then construes the leaf as already belonging in a certain sense to Nùàntaa; all she has to do is take it.

Position Matters: The Account of Action Must Work in an Enchronic Frame

Any research on human social life must choose one or more of a set of distinct temporal-causal perspectives, each of which will imply different kinds of research question and different kinds of data (Enfield Reference Enfield2014a). For example, there are well-established distinctions such as that between the phylogenetic evolution and the ontogenetic development of a structure or pattern of behaviour, or that between diachronic processes of the linguistic and historical past and the synchronic description of linguistic and cultural systems. Then there are perspectives that focus more on the ‘experience-near’ flow of time, and that lack established terms. The term microgenetic is sometimes used for the ‘online’ processes studied by psychologists by which behaviour emerges moment by moment within the individual. We are interested in something different from this, although it operates at a similar timescale. This is the perspective of enchrony, a perspective we argue is a privileged locus for studying social action.

An enchronic account focuses on ‘relations between data from neighbouring moments, adjacent units of behaviour in locally coherent communicative sequences’ (Enfield Reference Enfield2009:10; see also Enfield Reference Enfield2013:28–35). This means that the account must work in terms of sign-interpretant relations, to put it in neo-Peircean terms (Kockelman Reference Kockelman2005). From this perspective, to say that an utterance, as a sign, gives rise to an interpretant is to say that the utterance brings about a swatch of behaviour that follows the utterance (usually, but not necessarily, immediately), and where that following swatch of behaviour only makes sense in terms of the utterance it follows. The interpretant is not directly caused by a sign; rather, it orients to the object of that sign, that is, it orients to what the sign stands for. It is important to note that while interpretants are to some extent regimented by norms (see below), there is no one ‘correct’ interpretant of a sign. Many interpretants are possible.

Consider lines 13 and 14 from our example:

(6) 060808d (extract)

13 NT: [naaj] mez Aunty 14 ((0.7; Mnee turns gaze to Phiiw; Phiiw does not gaze to Nùàntaa))

In line 13 (see Figure 1.5a), Nùàntaa, sitting inside the doorway, her face visible, says naaj, which selects Phiiw, at centre of image in black shirt, her face turned away; within the subsequent second, in line 14 (see Figure 1.5b), Mnee, the child with the white shirt sitting in the doorway, turns her gaze towards Phiiw.

Taking Nùàntaa’s utterance naaj as a sign, we can see Mnee’s subsequent behaviour of turning her gaze as an interpretant of this sign, because the gaze redirection makes sense in so far as it is a reaction to Nùàntaa’s utterance, and it ‘points’ to what Nùàntaa’s utterance means. A normative expectation of the sign in line 13, which we have characterized as a summons to Phiiw, is that the addressee of the summons would display her recipiency for what is to come next (Goodwin Reference Goodwin1981; Kidwell Reference Kidwell1997). This expectation allows us to make sense of Mnee’s gaze redirection as an appropriate interpretant of the utterance. We mean it is appropriate in so far as the response is subprehended by the utterance – nobody is surprised when the response happens (see Enfield Reference Enfield2013:23 and 222, fn 28). Note also that sign-interpretant relations are subject to coherent analysis only as long as we specify the framing that we are using. We have just been discussing Mnee’s directing of gaze towards Phiiw in Figure 1.5b as an interpretant of Nùàntaa’s utterance in Figure 1.5a, but in a subsequent frame, we see that Mnee’s directing of gaze is itself a sign. If, for instance, we were to surmise that Mnee was looking to see how Phiiw would react, our surmising would be an interpretant of Mnee’s behaviour as itself a sign.

Since each interpretant is then a sign that begets another interpretant in turn, enchronic contexts move ever forward. And this ‘progressivity’ is evidently the preferred state of affairs (Stivers and Robinson Reference Stivers and Robinson2006). We see it in the next two lines of our example. While, as we have just seen, one might have expected to see Phiiw make an explicit display of recipiency to Nùàntaa, she in fact did not. This does not mean she is not attending, however, to what Nùàntaa is going to say to her next. Arguably, it is in line with a preference for progressivity that Nùàntaa takes a risk on the chance that Phiiw is not attending (also possibly allowing that non-response was within the bounds for this kind of utterance but not the request; cf. Stivers and Rossano Reference Stivers and Rossano2010) and instead goes ahead with the explicit request for some leaf. Then, however, in the following moments, as shown again here, Phiiw does not respond at all:

(7) 060808d (extract)

13 NT: [naaj] mez Aunty 14 ((0.7; Mnee turns gaze to Phiiw; Phiiw does not gaze to Nùàntaa)) 15 NT: piin sulaaq laa pass leaf prt Please pass some leaf. 16 ((1.0; Mnee keeps gaze on Phiiw; Phiiw does not gaze to Nùàntaa))

Figure 1.6 In line 15 (Fig. 1.6a), Nùàntaa produces the explicit request to Phiiw, at centre of image in black shirt, still turned away; in line 16 (Fig. 1.6b), Phiiw does not respond.

Line 16 constitutes an ‘official absence’ of response, a missing interpretant where one was in fact normatively due, or conditionally relevant (Schegloff Reference Schegloff1968; Sidnell Reference Sidnell2010a). We see evidence of this in that Nùàntaa is demonstrably within her rights to redo the summons that she had first issued at line 13. As shown again here, in (8) below, it is redone in line 17, though this time it can be heard as insistent, done at greater volume, and with a higher and more pronounced falling pitch excursion. Because of this special form, it sounds like it is ‘being done for a second time’. As can be seen in Figure 1.7b, this second doing of the summons now does receive the interpretant of ‘display of recipiency’ that might have been expected in line 14, though it is not only from Phiiw, but Phừà as well (line 19).

(8) 060808d (extract)

15 NT: piin sulaaq laa pass leaf prt Please pass some leaf. 16 ((1.0; Mnee keeps gaze on Phiiw; Phiiw does not gaze to Nùàntaa)) 17 NT: naaj= ((‘insistent’ prosody)) mez Aunty! 18 Sùàj: =pii qaa like hes Like um- 19 (0.5) ((Phiiw and Phừà both turn their gaze to Nùàntaa))

Figure 1.7 In line 17 (Fig. 1.7a), Nùàntaa redoes the summons, this time more ‘insistently’; in line 19 (Fig. 1.7b), both Phiiw and Phừà turn their gaze to Nùàntaa, and it is with this configuration in place that Nùàntaa makes the request for the second time (piin sulaaq in line 20).

Note how Phiiw’s behaviour of sitting doing nothing becomes meaningful in an enchronic context, quite unlike her behaviour of sitting doing nothing prior to line 13. Nùàntaa’s insistent-sounding redoing of the summons in line 17 is an interpretant of this ‘sign’, i.e., the behaviour of not doing anything at all in line 16.

Now that Nùàntaa has the recipiency of Phiiw and Phừà, she produces the request again, and then, in line 21, Phiiw and Phừà produce two different interpretants to Nùàntaa’s sign in line 20. Phiiw’s is an energetic interpretant: she feels in her pockets, as if to check whether she has any leaf at hand to give to Nùàntaa. Phừà’s is a representational interpretant: she produces a linguistic utteranceFootnote 2 that states where some leaf is (see Kockelman Reference Kockelman2005; Enfield Reference Enfield2013), as shown in (9):

(9) 060808d (extract)

19 (0.5) ((Phiiw and Phừà both turn their gaze to Nùàntaa)) 20 NT: piin sulaaq pass leaf Pass some leaf. 21 Phừà: sulaaq quu kuloong lêêh, leaf loc inside dem.up The leaf is inside up there, 22 sulaaq, quu khraa seeh leaf loc store dem.across the leaf, in the storeroom.

Again, we see the importance of the enchronic frame, and the notion that an utterance can be understood when it is seen as an interpretant of a prior sign. Any understanding of line 21 depends on the fact that it is placed right after the request in line 20. It is dependent on its position for what it does (i.e., as an instruction). Otherwise Phừà is just saying where some leaf is.

So we can see that in so far as each interpretant is itself a sign (or better, gives rise to another sign) each turn-at-talk is a kind of join in an architecture of intersubjectivity (see Heritage Reference Heritage1984; Sidnell Reference Sidnell, Enfield, Kockelman and Sidnell2014). So, for example, the talk at line 21 is an interpretant of the request, and it is in turn (eventually)Footnote 3 responded to by Nùàntaa’s getting up to follow the instruction to get some leaf herself.

(10) 060808d (extract)

21 Phừà: sulaaq quu kuloong lêêh, leaf loc inside dem.up The leaf is inside up there, 22 sulaaq, quu khraa seeh leaf loc store dem.across the leaf, in the storeroom. 23 (0.7) 24 Phừà: môôc cariit hanq one backpack 3sg (There’s) a (whole) backpack. 25 (5.0) ((Nùàntaa walks inside in the direction of the storeroom))

With the talk at line 23, Phừà adds a specification of what it is the recipient Nùàntaa should look for. This addition, which by its positioning appears to pursue response, could have been meant simply to help Nùàntaa locate the object (i.e., comparable to the instruction to ‘look for a backpack, not loose leaves’). But let us also note that by adding ‘whole backpack’, Phừà counteracts the underlying ‘giving’ assumption of the original request – it implies that ‘there’s plenty’ and therefore that there is no need to ask (the leaves represent a common and not an individual property).

Figure 1.8 In line 21, while Phiiw can be seen putting her hand into her pocket, as if to check whether she has any leaf at hand, Phừà responds verbally with a statement of the location of some leaf. At the beginning of line 21, Phừà is already turning her gaze back to her activity of preparing bamboo strips for basketry work.

We have tracked one line of action here; clearly there are others. We do not want to imply that there’s only one trajectory; rather, we see multiple lines of action unfolding simultaneously without that causing a problem for the participants. For example, while Nùàntaa is pursuing leaves to use in the preparation of a smoke, continuing talk is interspersed. At the same time, the smaller child is tracking the action throughout and thereby producing a kind of sub-action of ‘observation’ manifest in gaze redirection throughout.

Summary

By focusing in this opening chapter on a simple but illustrative example, we have pointed to the idea that actions gain their meaning and function from multiple sources simultaneously. We have explicated this in terms of three injunctions:

1. See that action is semiotic, i.e., it must be made publicly recognizable through some formal means.

2. See that action is culturally contextualized, i.e., actions are generated and interpreted against the shared background of participants in interactions.

3. See that action is enchronic, i.e., actions arise in sequences of move and counter-move, where each action stands as both a response to something, and a thing in need of response.

These points are central to much of what we will say in subsequent chapters. Now before moving to the core of the book in Parts II and III, we broaden our preliminary discussion of the concept of action, turning in Chapter 2 to some previous scholarship on action that supplies points of reference for our argument.