No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

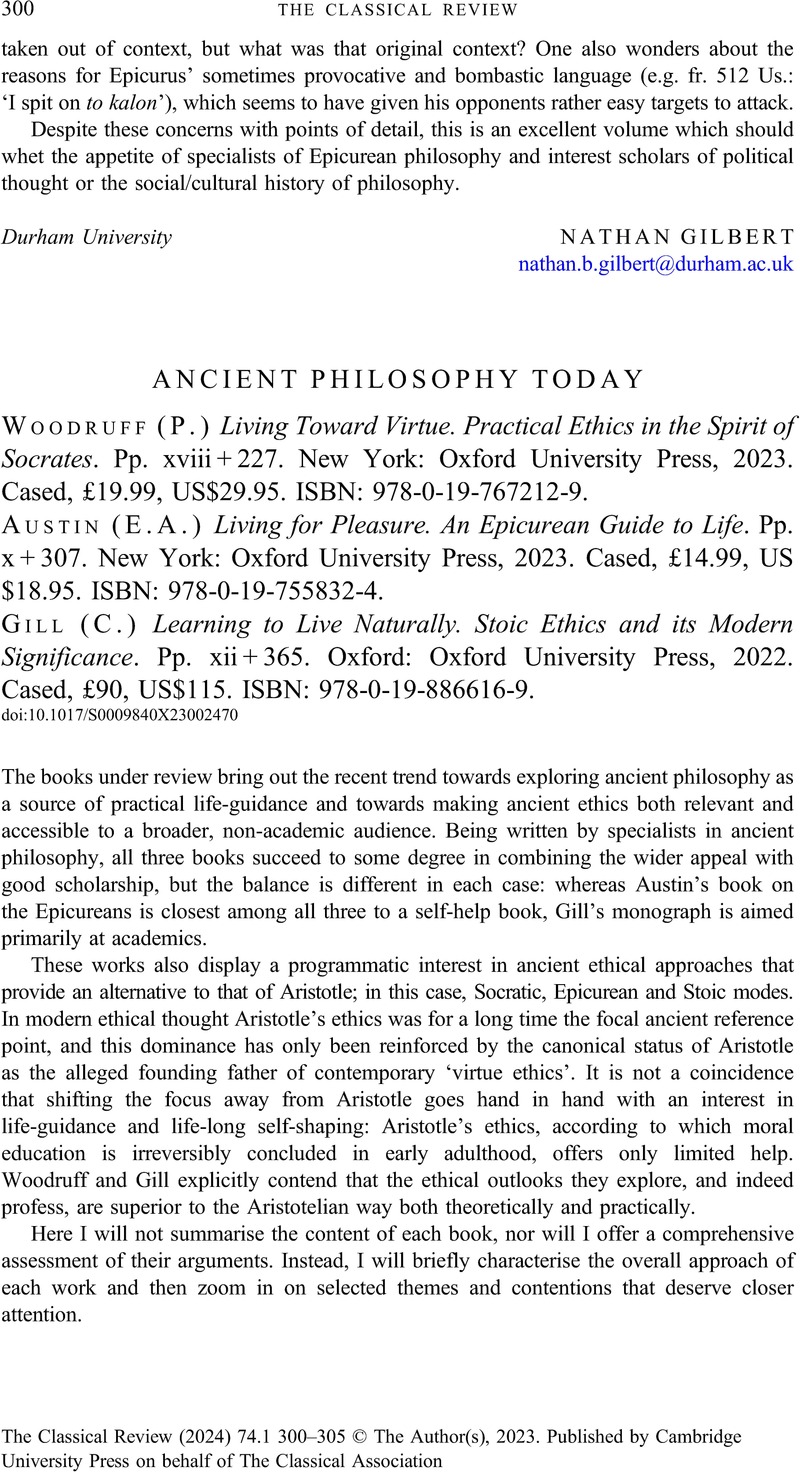

ANCIENT PHILOSOPHY TODAY - (P.) Woodruff Living Toward Virtue. Practical Ethics in the Spirit of Socrates. Pp. xviii + 227. New York: Oxford University Press, 2023. Cased, £19.99, US$29.95. ISBN: 978-0-19-767212-9. - (E.A.) Austin Living for Pleasure. An Epicurean Guide to Life. Pp. x + 307. New York: Oxford University Press, 2023. Cased, £14.99, US$18.95. ISBN: 978-0-19-755832-4. - (C.) Gill Learning to Live Naturally. Stoic Ethics and its Modern Significance. Pp. xii + 365. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022. Cased, £90, US$115. ISBN: 978-0-19-886616-9.

Review products

(P.) Woodruff Living Toward Virtue. Practical Ethics in the Spirit of Socrates. Pp. xviii + 227. New York: Oxford University Press, 2023. Cased, £19.99, US$29.95. ISBN: 978-0-19-767212-9.

(E.A.) Austin Living for Pleasure. An Epicurean Guide to Life. Pp. x + 307. New York: Oxford University Press, 2023. Cased, £14.99, US$18.95. ISBN: 978-0-19-755832-4.

(C.) Gill Learning to Live Naturally. Stoic Ethics and its Modern Significance. Pp. xii + 365. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022. Cased, £90, US$115. ISBN: 978-0-19-886616-9.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 December 2023

Abstract

An abstract is not available for this content so a preview has been provided. Please use the Get access link above for information on how to access this content.

- Type

- Reviews

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Author(s), 2023. Published by Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Classical Association