Introduction

For a variety of historical, geopolitical, and linguistic reasons, Turkmenistan and the Turkmen are notoriously understudied in the academic institutions of the Euro-Atlantic world. A few occasionally impressive exceptions notwithstanding, the great research library collections of North America and Western Europe are, likewise, sorely lacking in vernacular-language Turkmen materials, especially when compared to the totality of Turkmen-language publishing as reflected in the national bibliography of Turkmenistan (and especially in the works of Turkmenistan’s greatest bibliographer, Almaz Ýazberdiýew). The proportion of all Turkmen-language monographs published before 1929 that are held in even a single US library, for example, does not exceed 6%, or approximately 40 out of the 678 such monographs listed in Ýazberdiýew’s excellent Soviet-era bibliography (Iazberdyev Reference Iazberdyev1981).Footnote 1 For Turkmen-language works published after the abandonment of Arabic script in 1928, the picture is actually slightly worse, with approximately 5.8% of the post-1928 monographic works listed in the major bibliography for mid-20th-century Turkmenistan (Kuvadova, Panova, and Pirliev Reference Kuvadova, Panova and Pirliev1965) held in any US library.Footnote 2 Of the 87 post-1960 Turkmen-language periodical titles listed in the authoritative source on the journals and newspapers of Soviet Turkmenistan (Nazarova Reference Nazarova1989), US libraries hold one or more issues of only 12, meaning that 86% of them are not held in US libraries at all. Of the approximately 600 Turkmen-language monographic works published in Turkmenistan in the early 1990s (as reflected in the monthly issues of Turkmenistanyng metbugat letopisi, 1991–), US libraries hold about 29%.Footnote 3 Since 1997 it has become extremely difficult to obtain national bibliographic publications from Turkmenistan to use as a benchmark for assessing US library holdings, but based on my years of experience working in a major US library collection, I can personally attest to the difficulty of obtaining any Turkmen-language materials at all during the 2000s and 2010s.

There are several valid reasons for this state of affairs, including Turkmenistan’s long-standing near-inaccessibility for Euro-Atlantic scholars, librarians, and library vendors; extremely scant knowledge of the Turkmen language in North America and Western Europe, and extremely limited opportunities to learn it; the concomitant limited demand for such materials on the part of libraries and library users; and, therefore, the low priority placed on collecting Turkmen-language materials by most major Euro-Atlantic research libraries. None of this, however, should be construed as a judgment on the intrinsic interest of Turkmenistan and its history; on the intrinsic interest of Turkmen identity as a subject of study; on the intrinsic interest of literature and scholarship produced by Turkmens (in Turkmen, in Russian, and in other languages); on the intrinsic interest of the confluence of Turkmenistan’s abundant natural resources, its authoritarian system of government, and the geopolitical significance of both; or (most importantly for this article) on the intrinsic interest of the Turkmen diaspora. Adrienne Edgar’s Tribal Nation (Reference Edgar2004) and Victoria Clement’s Learning to Become Turkmen (Reference Clement2018), the two major English-language works on Turkmenistan, were both extremely well received and (based on their glowing reviews in Slavic Review [Smith Reference Smith and Edgar2005], Russian Review [Khalid Reference Khalid and Clement2019], The Journal of Modern History [Grant Reference Grant and Edgar2006], and elsewhere) have only whetted the Euro-Atlantic appetite for more research on this fascinating country and people.

But while the task that lies ahead for Euro-Atlantic scholars and libraries with regard to their Turkmen-related research and collections may seem straightforward based on the above (i.e., to do more), the virtually unknown publication history of the small Turkmen community of the North Caucasus raises many additional questions about the interplay of library collections and the scholarly record in the Euro-Atlantic world, and throws others into stark relief. How can our understanding of Turkmen identity ever be complete without considering how Turkmen diaspora communities think of themselves and their own identity? How can it be complete without considering how Turkmen diaspora communities are viewed inside Turkmenistan itself? Are they considered to be part of the greater Turkmen nation or not, and does the answer to that question vary depending on which diaspora community is under consideration, and on who is doing the considering? With regard to the Turkmen of the North Caucasus in particular, will we ever know the answers to these questions? Or, in time, will they become impossible to answer, because Euro-Atlantic libraries never bothered to collect any North Caucasus Turkmen publications before their community was transformed beyond recognition by climate change, war, revolution, environmental disaster, or draconian government policy (all of which are rather familiar phenomena in the region)? Questions like these, and the ways in which the Turkmen of the North Caucasus bring them into particularly sharp focus, will be explored in the pages that follow.

The Turkmen Diaspora and Its Publications

The Turkmen diaspora is defined differently depending on who is doing the defining. To some, virtually the entire Turkmen diaspora lives in Iran, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan, in close proximity to the borders of Turkmenistan itself, and numbers about one million people (vs. about five million inside Turkmenistan).Footnote 4 To others (including many Turkmen authors, especially those who wrote immediately following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, such as Durdyev and Kadyrov [Reference Durdyev and Kadyrov1991a, Reference Durdyev and Kadyrov1991b], Durdyev [Reference Durdyev1992], and Ataev [Reference Ataev1993]), the Turkmen diaspora numbers over 20 million and also encompasses the nomadic (or formerly nomadic) Yörüks of Anatolia and the Balkans, the descendants of the Ottoman-era Turkic populations of Jordan, Syria and Iraq, and the Salars of the Ili Valley and the Qinghai province of China, for a geographical range of over 4,000 miles from east to west.Footnote 5 As Sebastien Peyrouse puts it in his Turkmenistan: Strategies of Power, Dilemmas of Development, “According to Turkmen official data, there are about twenty-two million Turkmen in the world, or a diaspora of more than seventeen million people. More realistic studies put forward a figure of about four million for the Turkmen diaspora” (Reference Peyrouse2012, 62). Ýazberdiýew himself makes a point of including so-called “Turkmen” publications from Iraq in his 1981 bibliography.Footnote 6 It is not my purpose here to litigate these competing claims but rather to note that there is, in effect, a lively debate on the question of who is a Turkmen and who is not, and that this debate (in the pages of books, journals, newspapers, scholarly and pseudo-scholarly websites, and, increasingly, on social media) has been going on for many decades.Footnote 7

One particularly interesting (and woefully understudied) participant in this debate is the Turkmen government’s own attempt to manage this question: the Dünýa Türkmenleriniň Ynsanperwer Birleşigi (DTYB), or World Turkmen Humanitarian Association. This organization has (or has had) multiple branches in Russia, Central Asia, and as many as 30 countries worldwide, and it has also held an official congress in Aşgabat every year since its founding by Saparmyrat Nyýazow Türkmenbaşy in 1991. Current Turkmen president Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow assumed Nyýazow’s position as the titular head of this organization in 2007, and, like his predecessor, he typically addresses the congress as its keynote speaker.

Officially founded to offer “assistance in arranging cooperation with independent Turkmenistan, the preservation of national traditions and customs, and the revival of the ancient original Turkmen culture,” critics from the Turkmen diaspora and Turkmen political exiles characterize the entire organization as “window dressing” and a propaganda exercise (Tadzhiev Reference Tadzhiev2009). A particularly scathing critique was leveled in 2002 by Boris Şyhmyradow (the former Turkmen minister of foreign affairs, then in exile in Russia) and Myrad Esenow (a longtime Turkmen dissident then working as an academic in Sweden). The pair characterizes the association as a “fake institution” and diaspora participants in the annual congresses as crooks, rogues, and impostors who “lack authority in the Turkmen diaspora, and who are not able to represent its interests in the various countries in which it exists” (Shikhmuradov and Esenov Reference Shikhmuradov and Esenov2002). Şyhmyradow himself edited the proceedings of the 1993 congress (Shykhmyradov et al. Reference Shykhmyradov1993), but he is likely still a political prisoner in Turkmenistan after his arrest in 2002. His personal role in the DTYB, his later criticism of it, and his subsequent imprisonment place him and the DTYB at the very center of the debate on Turkmen diaspora identity and entangle it thoroughly in the questions of Turkmen government legitimacy explored by Polese & Horák (Reference Polese and Horák2015) and Denison (Reference Denison2009).

On the national and ethnic identity of the 15,000 Turkmen of the North Caucasus, however, there is no debate. Their migration around the northern shores of the Caspian Sea beginning in the 17th century is documented in the historical and diplomatic record and is associated with the simultaneous arrival of the Kalmyks in the region. The first Turkmen to live west of the Volga River served as bodyguards to the Kalmyk khan Kho-Örlök (c. 1580–1644). They were followed over the next 200 years by successive groups of Turkmen emigrants from what are now Turkmenistan and western Kazakhstan (Pan’kov Reference Pan’kov1960; Avksent’ev Reference Avksent’ev1996; Kurbanov Reference Kurbanov1995, 22–30, 34–35, 38–39). To Russian scholars of the 19th and early 20th centuries, they were known as the Trukhmen. In 1825, the greater part of their territories was organized into a Trukhmenskoe pristavstvo. In 1864 the future administrative and mercantile center of the North Caucasus Turkmen was established near the center of their summer pasturelands, hence its name–Letniaia Stavka (i.e., Summer Quarters or Summer Camp). The Turkmen territories were largely reorganized into a Turkmenskii raion in 1920 and then a Turkmenskii natsional’nyi raion (Turkmen National District) in 1925 (Akopian Reference Akopian2006, 95–96; Akopian Reference Akopian2009, 61; Tsutsiev Reference Tsutsiev2006, 64, map 22). The district’s national status was revoked sometime in the 1930s, and the district was abolished altogether in 1956. A much smaller Turkmenskii raion was reestablished in 1970. Today the North Caucasus Turkmen live in about 20 villages mostly concentrated in the Turkmenskii and Neftekumskii raions of Stavropol’ Krai (see fig. 1), with a historically related population living about 300 miles to the northeast near Astrakhan in the villages of Funtovo-1, Funtovo-2, and Atal.Footnote 8

Figure 1. Map of the Turkmen villages of Stavropol’ Krai, by the author. (Derived from Виктор В, “Relief Map of Stavropol Krai,” Wikipedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Relief_Map_of_Stavropol_Krai.jpg.)

As dire as the situation may be regarding Turkmen-language publications from Turkmenistan in Euro-Atlantic libraries (as described above), for Turkmen diaspora publications it is even worse. As a rough indicator of the scale of the problem, as of February 2020 there are 6,522 titles with the primary language code “tuk” (i.e., Turkmen) in WorldCat.Footnote 9 (Many of these are duplicate records for the same book or journal or newspaper, so the true total of Turkmen-language titles held in the over 70,000 [primarily Euro-Atlantic] library collections represented in WorldCat may be closer to 4,000.)Footnote 10 Of these, about 87% were published in Aşgabat (also represented in WorldCat as Ashgabat, Ashkhabad, Ašchabad, Poltoratsk,Footnote 11 Askhabad, Ashabat, Ashabad, Ashhabat, Asxabad, Acgabat,Footnote 12 Asrabat [sic], Asgbad [sic], etc.), leaving about 850 records (some of which, as noted above, are duplicate records for the same item). Of these, about 165 are for items published in other towns and cities within the current borders of Turkmenistan, and a further 110 were published in Tashkent, Moscow, or Leningrad/St. Petersburg. Before 1929, these latter tended to be published on behalf of Turkmen institutions that lacked printing presses with Arabic movable type, and after 1929, they tended to be major Turkmen-Russian dictionaries or large-format multilingual works on Turkmen art or architecture.

That leaves approximately 575 catalog records, or 9% of the total, to account for all other Turkmen-language publications. Approximately 250 of these are language-learning materials, museum exhibition catalogues, or recordings of Turkmen music published in Western Europe or North America. Approximately 30% of the remainder seem to have been coded erroneously as Turkmen-language materials,Footnote 13 leaving about 225. Approximately 60 of these were published in Istanbul or Ankara, but rather than being productions of the pre-1917 Turkmen diaspora (which, in the context of modern Turkey, is usually identified with the seminomadic Yörük population of eastern Anatolia), most of them seem to be part of the general Turkish enthusiasm for the literatures of Turkic peoples from all over Eurasia.Footnote 14 That leaves approximately 165 catalog records in WorldCat to account for virtually the entire publication history of the Turkmen diaspora, and many of these, as noted above, are duplicate records for the same items. A few dozen of these are for Iraqi publications coded as Turkmen, many of them published before and (especially) after the 1969–1976 window included in Iazberdyev (Reference Iazberdyev1981), and a few dozen more are for Iranian publications, many of them from cities near the Iranian-Turkmen border.

As for vernacular-language publications emanating from the Turkmen community of the North Caucasus, it appears that out of all of WorldCat’s four billion catalog records, there is exactly one, for a single copy of a 75-page book of poetry published in Aşgabat by a North Caucasus Turkmen in 1994. The details regarding this publication, along with the others unearthed in the course of my research, will be provided later in this article. First, however, the place (or lack thereof) of the Turkmen diaspora in Euro-Atlantic scholarship (especially in contrast to its treatment in the Russian, Turkish, and Turkmen scholarly literature) must be considered.

The Invisible Diaspora of a Nearly Invisible Country

At least partly because of the almost complete absence of materials in Euro-Atlantic library collections, no Euro-Atlantic scholar in any discipline seems to have engaged with the North Caucasus Turkmen in a sustained or serious way. Their existence has been acknowledged, at least, in the works of Ronald Wixman, who mentions them in passing several times in his Language Aspects of Ethnic Patterns and Processes in the North Caucasus (Reference Wixman1980, 66, 88, 95, 111). The only substantive statement Wixman makes about the North Caucasus Turkmen is in his The Peoples of the USSR: An Ethnographic Handbook (Reference Wixman1984), and unfortunately it is misleading on several points. His entry on the North Caucasus Turkmen (i.e., the Trukhmen, as noted above) reads as follows:

TRUKHMEN. Oth[er] des[ignation] Trukhmen (Turkmen) of Stavropol.… The Trukhmen are the descendants of Turkmen from the Mangyshlak Peninsula region of TurkmenistanFootnote 15 who settled in the Nogai steppe in the North Caucasus in the 17th cent[ury]. They have been strongly influenced by the Nogai in that region, and in the past were being assimilated by them. … The dialect of Turkmen spoken by them has been strongly influenced by Nogai and Russian. It differs greatly from the Turkmen dialects of Turkmenistan. The Trukhmen use the Nogai and Russian literary languages (not Turkmen). Population 4,533 (1926). In the 1926 census the Trukhmen were listed as Turkmen. The Trukhmen are being assimilated by the Nogai. They are Sunni Moslem in religion. They live, primarily, in Stavropol Krai in the steppe region of the North Caucasus. (Wixman Reference Wixman1984, 194; italics added for emphasis)Footnote 16

As will be shown below, although the Turkmen of the North Caucasus certainly did write and publish in Russian, and although it is plausible (given the several decades of Nogai-language primary school education to which they were subjected; see Brusina [Reference Brusina2008, 34] and Yliasov [Reference Yliasov1994, 3]) that they also wrote and published in Nogai, they also wrote and published works in their native language, and as of 2020 they seem to have rather successfully resisted assimilation into the Nogai ethnos. Yet the way they are treated in subsequent Euro-Atlantic scholarship suggests that Wixman’s dismissive comments reflect some kind of inadvertent consensus, namely, that the North Caucasus Turkmen have never published anything and are therefore not worthy of serious study. As with the monographs discussed below, it is ultimately not my intention to criticize Wixman’s work. Certainly the compilation and interpretation of the rather remarkable amount of information Wixman communicates in these two monographs would be difficult (and very welcome) in any epoch, but particularly in the late 1970s and early Reference Wixman1980s, when Euro-Atlantic knowledge of the North Caucasus and many of the Soviet Union’s smaller ethnic groups was minimal.

Among the few English-language scholarly monographs to cover Turkmenistan in a substantive fashion is Peyrouse (Reference Peyrouse2012), mentioned above. Atypically, Peyrouse does include two pages devoted to the Turkmen diaspora, these pages do actually mention the Turkmen of the North Caucasus, and (nearly uniquely in all of Euro-Atlantic scholarship) Peyrouse actually cites a Russian-language source on the North Caucasus Turkmen (Reference Peyrouse2012, 62–63).Footnote 17 In contrast, the North Caucasus Turkmen appear only once in the two main English-language works on Turkmen national identity mentioned above: Adrienne Edgar’s Tribal Nation: The Making of Soviet Turkmenistan and Victoria Clement’s Learning to Become Turkmen: Literacy, Language and Power, 1914–2014.Footnote 18 It would be disingenuous, however, to criticize either of them for this lack of attention; Edgar and Clement write about the formation of national identity within Turkmenistan’s current borders, not elsewhere, and without Edgar (Reference Edgar2004), Clement (Reference Clement2018), Peyrouse (Reference Peyrouse2012), and at most a handful of other works, there would be no book-length scholarly treatments of any aspect of Turkmen identity or Turkmen history and culture in the English language. Clement does mention the fact that the purges of the 1930s accused the Turkmen diaspora in Iran of being in league with British imperialists (Reference Clement2018, 74), and Edgar devotes a fair amount of space to the emigration to Iran and Afghanistan of Turkmen families fleeing early-Soviet economic, political, and cultural disruptions (Reference Edgar2004, 213–220), although the diaspora communities there (and their experience of Turkmen identity) are not explored any further. The presence of an unknown number of early- to mid-20th-century Soviet émigrés in geographically-contiguous diaspora communities would seem to add to the inherent scholarly interest of those communities, but the border areas of Iran and Afghanistan have been difficult and dangerous regions for most Euro-Atlantic scholars to conduct research in for several decades now.Footnote 19

The other major English-language scholarly monograph on Turkmenistan is S. Peter Poullada’s Russian-Turkmen Encounters: The Caspian Frontier before the Great Game (Reference Poullada and Styron2018), which, despite its unrelenting focus on the role of various Turkmen tribes in relations among the Russians, Kalmyks, and Uzbeks at the exact time that Turkmen migration to the North Caucasus was occurring, and even noting that “by the mid-1640s a mass migration out of Mangyshlak was under way” (46), makes no mention of the North Caucasus Turkmen. Again, it is not my purpose to criticize the few (and therefore very welcome) English-language scholarly monographs that wrestle with the history, culture, and national identity of the Turkmen; I am merely pointing out that, not surprisingly, those few English-language scholarly monographs on Turkmenistan that do exist almost completely ignore the existence of Turkmen diaspora populations that might shed light on the nature of Turkmen-ness in the modern world—and in particular, they ignore the nearly 400-year-old Turkmen community of the North Caucasus.

To consider this state of affairs from another angle, English-language works about the North Caucasus or the Russian imperial frontier in general are equally silent (or nearly so) on the Turkmen of the North Caucasus. There are, for example, two entries for “Turkmen(s)” in the index to Marie Bennigsen Broxup’s The North Caucasus Barrier: The Russian Advance towards the Muslim World, but one of them refers to the infamous Russian massacre of the Turkmen at Gökdepe near Aşgabat in 1881 (Broxup Reference Broxup1992, 9), and the other refers to the inability of the Soviet Union to persuade the Turkmen of Afghanistan to join the Soviet cause during the Soviet-Afghan War of 1979–1989 (23). The North Caucasus Turkmen receive two sentences in Cambridge’s 898-page The Caucasus: A History (Reference Forsyth2013, 237), and award-winning historian Willard Sunderland devotes three sentences to the settling of Russian internal migrants on Nogai and North Caucasus Turkmen land in the late 19th century in his Taming the Wild Field (Reference Sunderland2004, 193–194).Footnote 20 (In a work that covers Russian colonization across the entire western Eurasian steppe beginning in the 9th century, however, this could be considered an appropriate level of attention.) There is no mention of the Turkmen in Alex Marshall’s otherwise-excellent account of the history of the North Caucasus since the 19th century (Reference Marshall2010). And finally, despite the strong focus on Stavropol’ Krai in Andrew Foxall’s Ethnic Relations in Post-Soviet Russia: Russians and Non-Russians in the North Caucasus (Reference Foxall2015), the North Caucasus Turkmen do not appear in the index, and are only mentioned in passing as one of the region’s minority populations (60, 62–63, 67).

As far as German- and French-language monographic works and dissertations on Turkmenistan are concerned, their field of inquiry tends to be even more focused on Turkmenistan itself, and, accordingly, the North Caucasus Turkmen do not, to the best of my knowledge, make an appearance (e.g., Fénot and Gintrac Reference Fénot and Gintrac2005; Rousselot Reference Rousselot2015; Ashirova Reference Ashirova2009; Maghsoudi Reference Maghsoudi1987). German and French works that focus on the North Caucasus, like their English counterparts, also treat the region’s Turkmen population cursorily or not at all; the North Caucasus Turkmen are not, for example, mentioned anywhere in Jeronim Perović’s 544-page Der Nordkaukasus unter russischer Herrschaft (Reference Perović2015), apart from their inclusion on two of the maps at the end of the book (496, Karte 2, 501, Karte 7). Even in Ingeborg Baldauf’s 782-page Schriftreform und Schriftwechsel bei den muslimischen Russland- und Sowjettürken (1850-1937) (Reference Baldauf1993), the North Caucasus Turkmen are nowhere to be found, despite a whole chapter on alphabet reform among the neighboring Nogais, Karachais, Balkars, and Kumyks (310–315), several pages on the development of alphabets for non-Turkmen peoples within Turkmenistan and for Turkmen groups outside Turkmenistan (561–563), and a detailed chronology of Turkmen orthographic reforms (699–702).

The same appears to be true of the Euro-Atlantic periodical literature. The Turkmen of the North Caucasus are occasionally mentioned, but they never appear as the object of scholarly study in their own right. For example, while the results of keyword searches in JSTOR for articles and book chapters that contain both the word turkmen and the word caucasus (1,240 results), turkmen and stavropol (68 results), or turkmen and kaukasus (56 results) are encouraging at first glance, upon further examination it emerges that almost none of these have anything to do with the Turkmen of the North Caucasus. Of those that do, the following examples are typical: one line in a 38-page article pointing out that the Nogai and North Caucasus Turkmen belong to the Hanafi school of Islamic jurisprudence, as opposed to their Shafi’i neighbors to the south in Daghestan (Malashenko and Nuritova Reference Malashenko and Nuritova2009, 345); one line in a 37-page article describing the harassment of Russian peasant migrants to the North Caucasus by “Kalmyk, Nogai and Turkmen nomads” (Seregny Reference Seregny2001, 93); one mention of the migration of Mangyshlak Turkmen to the North Caucasus in a footnote in a 33-page article (Bregel Reference Bregel1981, 18n33). As a more recent example, Allen Frank’s (Reference Frank2020) article on literacy, education, and identity among the Turkmen makes some interesting arguments about pre-1917 Turkmen identity, but he makes no mention whatsoever of Turkmen communities in Iran, Afghanistan, the North Caucasus, or anywhere else in the diaspora.Footnote 21 Finally, the Index Islamicus database contains entries for 1,703 articles having to do with Turkmenistan and the Turkmen, but if any of them make any mention of the Turkmen of the North Caucasus, it is not immediately apparent.

Even the searchable full text of the two million English-language dissertations digitized in ProQuest’s Dissertations and Theses database yields only a handful of references to the North Caucasus Turkmen. Sean Pollock quotes a passage from the famous botanist and traveler Peter Pallas’ account of traversing the North Caucasus Turkmen lands in 1793 (Reference Pollock2006, 63–64); Aaron Michaelson mentions the efforts of the Russian Orthodox Missionary Society among the North Caucasus Turkmen in the late 19th century (Reference Michaelson1999, 228–229, 343–345); and Charles Reiss expends a few lines on one of the waves of Turkmen migration to the North Caucasus in the 18th century (Reference Reiss1983, 297).Footnote 22 But as of February 2020, not a single full-text-searchable dissertation in the database appears to do more than touch on the North Caucasus Turkmen in passing.

Despite appearances, it is not my intention to belabor the failings of Euro-Atlantic libraries and scholarship to the point that the reader thinks I am personally offended by this state of affairs. Rather, I think it is important to establish a clear and conclusive picture of the status of marginalized groups and their publications in the Euro-Atlantic world so that remedial actions can be taken, not only with regard to the Turkmen diaspora but also with regard to diasporas and marginalized groups all over the world.

Furthermore, this rather lengthy survey of the near-total absence of the North Caucasus Turkmen from Euro-Atlantic scholarship will be contrasted later in the article with the much better coverage of this group in the Russian, Turkish, and Turkmen scholarly literature. That literature has been essential in illuminating the publication history of the North Caucasus Turkmen themselves. There is also the question of whether even the best-intentioned Euro-Atlantic library could have actually acquired North Caucasus Turkmen publications at any point in the last 100 years, or whether this could be accomplished today. Certainly, vendors of materials from Eurasia could be forgiven for concluding that there was not much of a market for North Caucasus Turkmen materials in Euro-Atlantic libraries and that there was not much profit to be made on them in any case. But Euro-Atlantic libraries have nevertheless managed to end up with all manner of unlikely items in their collections through working with vendors, soliciting and accepting donations, and taking matters into their own hands through buying trips. There is no reason why North Caucasus Turkmen publications could not benefit from the same combination of determination and luck. If Princeton can acquire manuscripts from the personal library of Imam Shamil,Footnote 23 Stanford’s Hoover Institution can acquire rare newspapers from all over (what would become) the Soviet Union during the Russian Revolution and Civil War (Maichel Reference Maichel1966), the Library of Congress can acquire the entire collection of the Siberian bibliophile Gennadii Vasil’evich Iudin (Dash Reference Dash2008; Kasinec Reference Kasinec2008; Leich Reference Leich2008), the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign can acquire virtually the entire national bibliography of Uzbekistan in digital form,Footnote 24 the British Library can acquire over 1,000 periodicals in dozens of Turkic languages (Waley Reference Waley1993), and two dozen libraries in North America and Western Europe can acquire a microfilm set of 6,000 early-20th-century Russian newspapers that were only in existence for a single day (Russian National Library 1994), then surely some library somewhere in the Euro-Atlantic world can make a point of collecting North Caucasus Turkmen materials, while others focus on other similarly marginalized and ignored groups. And as will be seen below, Euro-Atlantic scholars have barely scratched the surface of the massive trove of primary-source material contained in the thousands of newspapers published in the Russian Empire, the Russian Federation, and, especially, the Soviet Union.

Publications of (and on) the North Caucasus Turkmen

The standard bibliographic source for Soviet-era newspapers is the aptly named Gazety SSSR, which boasts 12,875 individual entries for every national, regional, local, and military newspaper whose existence was known to the compilers in the late Soviet era (Episkoposov Reference Episkoposov1970–1984). It contains entries for 200 different newspapers filed under the Russian title Leninskoe znamia (The Leninist Banner), 12 entries for newspapers filed under the Russian title Znamia leninizma (The Banner of Leninism), and 51 entries for newspapers filed under the Russian title Znamia Lenina (Lenin’s Banner). Among these latter are a Lenina bairaghy published in Azerbaijani in the Daghestani city of Derbent beginning in 1920 (2:426, entry no. 4511), a Stsiah Lenina published in Belarusian in the village of Svetilovichi in the Homel region of Belarus’ from 1935 to 1956 (2:431, entry no. 4533), and a Sztandar Lenina published for the Polish-speaking community of Širvintos, Lithuania, from 1950 to 1957 (2:433, entry no. 4546). Hidden among this cluster of Lenin’s Banners it is also possible—via looking up “Letniaia Stavka” in the geographical index of places of publication—to find one from the Turkmenskii raion of Stavropol’ Krai in the North Caucasus, and, buried in the fine print of the entry, to learn that this newspaper included Turkmen-language content in 1935, 1936, 1940, and possibly earlier in the 1930s as well (2:429, entry no. 4522). Its Turkmen title was Lenin baýdagy, or Lenin baidagy in its transliterated Cyrillic guise, and to the best of my knowledge, no Euro-Atlantic library possesses so much as a single issue of it in any format. Yet in and of itself, Lenin baýdagy’s presence in the most authoritative bibliography of Soviet-era newspapers not only disproves Wixman’s assertion, but also makes the prospect of studying the North Caucasus Turkmen using their own published works from the past 85 years or more much less dubious.

Further evidence along these lines is provided by Güneş (The Sun), another Turkmen-language newspaper published in Letniaia Stavka in the 1990s.Footnote 25 Although its existence is attested to in numerous sources, it is a bibliographic ghost, absent from the usual Soviet and Russian newspaper bibliographies, lacking any kind of online presence (whether current or retrospective), and, like Lenin baýdagy before it, completely absent from any known Euro-Atlantic library collection. Some of the most detailed information on Güneş comes from a volume of poetry published in Aşgabat in 1994 with the tantalizing title Stavropoldan salam (Hello from Stavropol; see fig. 2). The foreword to this volume explains that the poet, Jumahaset Ylýasow, is a Turkmen from the village of Ozek-Suat in the Neftekumskii District of Stavropol’ Krai who grew up learning Nogai and Russian in local schools, but taught himself literary Turkmen later in life, and made a point of teaching it to his children as well. His son, Jepbar Ylýasow, was serving as the editor of Güneş as of 1994 (Yliasov Reference Yliasov1994, 3–4). The elder Ylýasow was also involved in the compilation of a book of North Caucasus Turkmen proverbs and sayings published by the Turkmen Academy of Sciences in Aşgabat in 1982 (Veliev and Yliasov Reference Veliev and Yliasov1982).Footnote 26

Figure 2. The cover of Jumahaset Ylýasow’s Stavropoldan salam (Hello from Stavropol’), published in Aşgabat in 1994.

One of the best accounts of North Caucasus Turkmen culture in the 20th century is Sapar Kürenow’s (Reference Kurenov1962) Stavropol’ Turkmenleri khem-de olaryng medeni bailygy (The Stavropol’ Turkmen and their cultural riches). This volume is held at only five Euro-Atlantic libraries (and none in the USA), but the 1995 Turkish-language version (Kürenov Reference Kürenov and Duymaz1995) is more widely available. In it, Kürenow mentions the existence of a three-act Turkmen-language play published “privately” (özbaşdak/müstakil)Footnote 27 in the North Caucasus in 1926 (Kürenov Reference Kürenov and Duymaz1995, 76.). While this particular edition of the play has thus far proven impossible to verify bibliographically, Kürenow’s claim does lend credence to the idea that during the late 1920s, when virtually every other ethnic group in the North Caucasus was experimenting with new alphabets, engaging in massive literacy campaigns, and publishing original vernacular-language works and translations of Russian-language works in all genres and formats, the North Caucasus Turkmen, in their newly minted Turkmen National District, were doing the same. Lending more credence to this idea is the fact that the same play was (re)published in Moscow in 1928, as attested in no less than five contemporaneous and retrospective bibliographies.

The multiple guises in which this play appears in these bibliographies underscores the general difficulty of tracking down North Caucasus Turkmen publications. Originally, of course, it was published in Arabic script, but it is only in the last 10–15 years that online library catalogs have been able to display non-Roman scripts correctly, and simply copying the Arabic script into a Euro-Atlantic library catalog would unnecessarily cut this play off from scholars and other library users and staff who can read a Turkic language—or who could simply understand what this item is by looking at a catalog record—but cannot read Arabic script. In other words, the conversion (or, more precisely, the transliteration) of the original Arabic-script information into Latin script is an important part of making this work accessible to scholars.

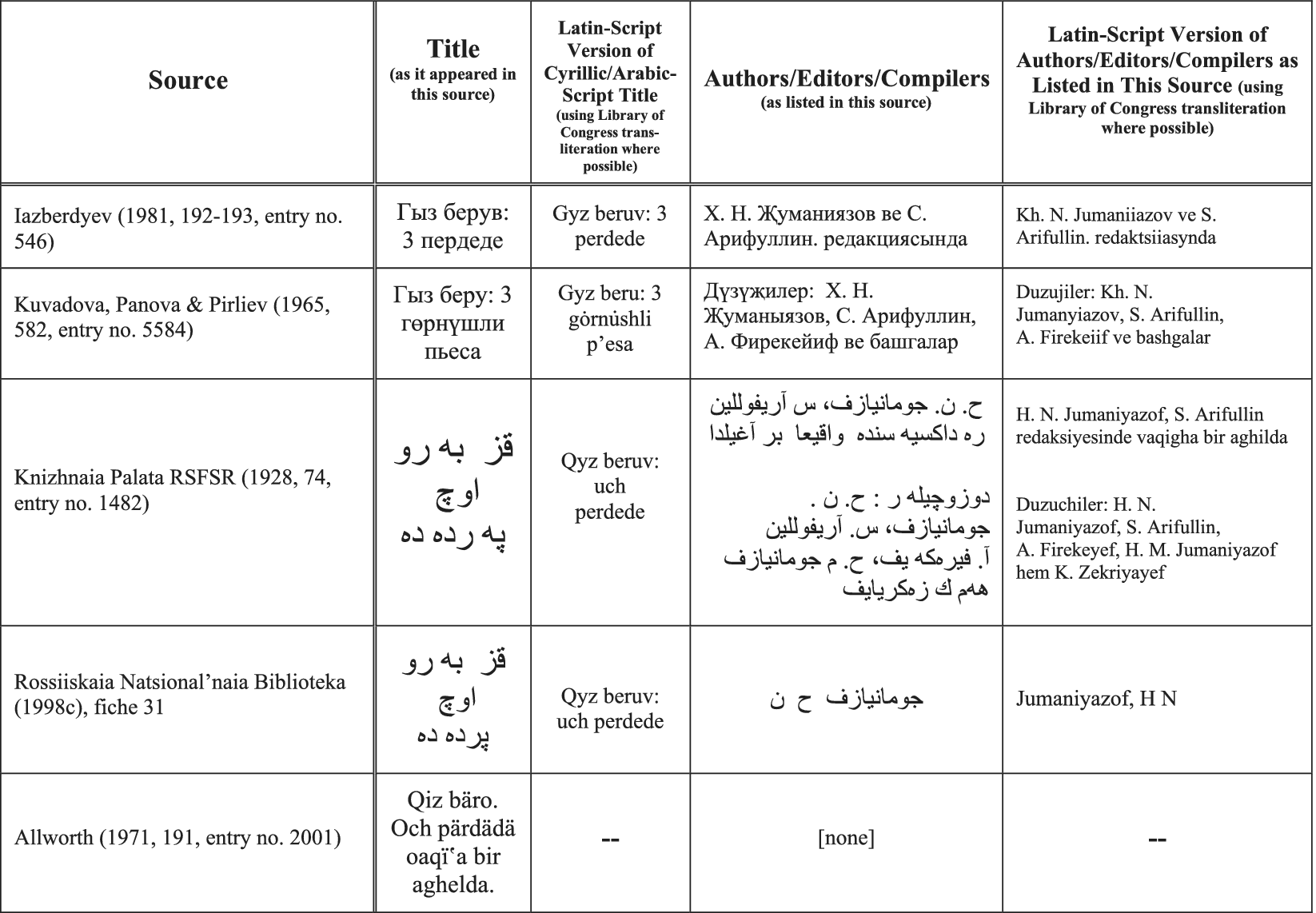

And yet as of 2020, there is still no standard Euro-Atlantic system for transliterating Arabic-script Turkmen into Latin characters, nor can experts, even in Turkmenistan itself, agree on how to read the original Arabic script in the first place. Ýazberdiýew gives the original Arabic-script title as قز بە رو, but problems arise when various attempts to transliterate it into Cyrillic and Latin script are made (see figure 3).

Figure 3. The 1928 Moscow edition of Hajynazar Jumanyýazow’s play Gyz beruw as represented in various bibliographic sources

The bottom row of this table is of particular interest, since the source cited (Edward Allworth’s Nationalities of the Soviet East: Publications and Writing Systems; A Bibliographical Directory and Transliteration Tables for Iranian- and Turkic-Language Publications, 1818-1945, Located in U.S. Libraries [Reference Allworth1971]) is, as the title indicates, based on items that are actually held in US libraries and that, therefore, are theoretically available to Euro-Atlantic scholars. Allworth’s transliteration, however, is the worst of the five, seemingly suffering from the conviction that the Arabic-script letter “و” should always be transliterated as “o,” when it just as commonly stands for “w,” “v”, “u”, “ü”, or “ö.” In any case, the sum total of Euro-Atlantic holdings of publications that can be attributed to the Turkmen of the North Caucasus appears to be two: one copy of Stavropoldan salam, held at the Library of Congress, and the New York Public Library’s single copy of Gyz beruw, which, despite being acquired nearly 100 years ago, has still not been added to their online catalog as of February 2020.Footnote 28

Given the difficulty of identifying and locating many of the publications listed above, it is challenging to estimate the full extent of North Caucasus Turkmen publishing activity, but there are indications that more materials exist. In his article on the North Caucasus Turkmen in the 21-volume encyclopedia Türkler, Ali Duymaz mentions a certain Gurban Hajymuhammedow (Hacımuhammedov) (1894–) who was active as poet during the Soviet era, as well as the existence of a four-act play by a Murtaza Jumanyýazow (Cumanıyazov) (Duymaz Reference Duymaz, Güzel, Çiçek and Koca2002, 924).Footnote 29 Ol’ga Brusina’s Turkmeny Iuga Rossii (Reference Brusina2016a, 186–187) includes references to the currently active folk poet Ş. U. Taganyazow (Sh. U. Tagan’iazov), to the local Turkmen cultural organization Vatan, and to other signs of potential publishing activity. Brusina also includes information on the Astrakhan Turkmen farther to the northeast. Brusina (Reference Brusina and Dubova2016b, 471, 491–492) also mentions a Dzhumaset Il’iasov, perhaps a relative of the publisher of Güneş and of the author of Stavropoldan salam, who was gathering folklore, translating Arabic poetry into Turkmen, writing his own poetry, and attempting to develop a literary language based on the North Caucasus dialect of Turkmen in the mid-2000s.

Logical next steps in identifying additional North Caucasus Turkmen publications would include fieldwork in Stavropol’ Krai, as well as a thorough investigation of what is likely the largest collection of Turkmen-language materials currently available to Euro-Atlantic scholars: the Turkmen collection of the Department of the Literature of the Nationalities of the former Soviet Union at the Russian National Library (RNL) in St. Petersburg. The RNL’s entire card catalog of its Turkmen-language holdings (numbering approximately 20,000 items in all) was duplicated on microfiche in 1998, and these microfiches are held at four US libraries,Footnote 30 giving Euro-Atlantic scholars the opportunity to attempt to identify North Caucasus Turkmen publications among the RNL’s excellent holdings (among other, less specialized pursuits) even before they travel to St. Petersburg.

Tracing the complete publishing history of the North Caucasus Turkmen, then, is still a bit out of reach. In the meantime, my argument is not that the handful of published North Caucasus Turkmen works described above are exceptionally valuable, or that they amount to some kind of significant corpus of primary sources; rather, the mere fact that these sources exist at all is significant. If, with a bit of determination and bibliographic expertise, primary-source publications for a group as overlooked and ignored as the Turkmen of the North Caucasus can be found, then the work that remains to be done (and that can be done) by Euro-Atlantic scholars and librarians on peoples throughout the Caucasus, Central Asia, and beyond must be massive indeed. Even for the 15,000 Turkmen of the Russian Federation, there are sources—and said sources can, with a bit of luck and know-how, be identified via secondary works and bibliographies held in Euro-Atlantic libraries, before having to contact local scholars, authors or librarians or traveling to the region in person.

As for the intrinsic value of these few North Caucasus Turkmen sources, it must be said that perhaps Gyz beruw and other dramatic works from the 1920s, if any, are puerile and derivative. Perhaps the Turkmen-language articles in Lenin baýdagy during the 1930s consist of stultifying propaganda or are simply reprinted from the newspapers of Turkmenistan. Perhaps Güneş is full of bad poetry, wedding announcements, and speculations about the weather. But with (almost certainly) no more than two works ever published by any North Caucasus Turkmen held in any library in the Euro-Atlantic world (and each of those existing in only one copy), and (almost certainly) no engagement with any work ever published by any North Caucasus Turkmen anywhere in the gigantic corpus of Euro-Atlantic scholarship, as of 2020 we still have no idea what these sources contain. And even if, for example, the articles in Lenin baýdagy consist of nothing but reprints from Aşgabat newspapers, Euro-Atlantic library holdings of pre-WWII Turkmen newspapers are none too strong in any case, so a series of articles that were reprinted in the North Caucasus would be most welcome. Of the 61 regional and local newspapers described in great detail by Nazarova (Reference Nazarova1989, 90–288), for example, precisely zero are held at any library in Western Europe or North America. The choice of which articles were reprinted for a North Caucasus audience is also of potential scholarly interest, as well as, for linguists and scholars of language reform, the lexicon and orthography used in the text itself. The same is true for other pre-WWII publications such as Gyz beruw, even if it makes for mediocre theatre, and even for Güneş, despite the fact that it may have little to say on the major issues of the day.

Although Wixman’s contention that the North Caucasus Turkmen wrote only in Russian and Nogai is no longer tenable, some consideration should also be given to publications by North Caucasus Turkmen in other languages. Chief among these are the Russian-language works of Mahmyt Tumaýylow (Mahmut Tumailov, Makhmud Tumailov), who was born in Malyi Barkhanchak in 1902 and died in Magadan in 1937, having served as a delegate to the 1920 Baku Congress of the Peoples of the East, as the finance commissar for the Turkmen SSR, and as a declared member of the Trotskyist opposition in the mid-1920s, while also completing a monograph on the North Caucasus Turkmen, which was confiscated by the NKVD.Footnote 31 Although this monograph was written in Russian rather than Turkmen, it is likely one of the most substantial and most interesting works ever produced by a Turkmen native of the North Caucasus.

Other substantial works on the North Caucasus Turkmen by Tumaýylow’s coethnics in Turkmenistan itself, and by interested scholars in Russia and in Turkey, are relatively plentiful, as demonstrated by the many Russian-, Turkmen-, and Turkish-language sources cited above. Sapar Kürenow is one of the most prolific Turkmen scholars on the subject of his coethnics in the North Caucasus. Interested Turkish scholars include the abovementioned Ali Duymaz (Reference Duymaz2015), Sema Aslan Demir (Reference Demir2015), and Savaş Şahin (Reference Şahin2015), all of whom contributed to the section on the North Caucasus Turkmen in a special issue of Yeni Türkiye covering the Turkic peoples of the North Caucasus. Prominent Russian scholars of the North Caucasus Turkmen include A. V. Kurbanov, a fellow at the St. Petersburg branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Ethnography & Anthropology (IEA RAN), who wrote several works about the North Caucasus Turkmen in the 1990s, most notably his 237-page monograph Stavropol’skie turkmeny (Reference Kurbanov1995). In the 2000s and 2010s, the primary scholar writing in Russian about the North Caucasus Turkmen was Ol’ga Brusina, a fellow at the main branch of IEA RAN in Moscow, several of whose works have already been cited above (Brusina Reference Brusina2008, Reference Brusina2016a, Reference Brusina and Dubova2016b).

The Turkmen of the North Caucasus also attracted the attention of several Russian scholars in the early 20th century, most spectacularly Ivan L’vovich Shcheglov, whose four-volume treatise on the Turkmen and Nogai of Stavropol’ province runs to over 2,000 pages (Reference Shcheglov1910–1911). Russian ethnographic journals of the time featured a number of articles on the North Caucasus Turkmen (e.g., Bregel Reference Bregel1995, 2:1116–1122),Footnote 32 including S. V. Farforovskii’s “Trukhmeny (Turkmeny) Stavropol’skoi gubernii” (Reference Farforovskii1911), a report entitled “Sredi stavropol’skikh turkmenov i nogaitsev i u krymskikh tatar: otchet o komandirovke v 1912 g.” by the great Ukrainian Turkologist A. N. Samoilovich (Reference Samoilovich1913), and two articles by A. Volodin in Sbornik materialov dlia opisaniia mestnostei i plemen Kavkaza (Reference Volodin1908a, Reference Volodin1908b). The latter article by Volodin contains a 1902 photograph of a North Caucasus Turkmen extended family (see fig. 4) as well as what is arguably the first instance of a North Caucasus Turkmen text appearing in print (see fig. 5). Volodin’s primary source material was collected directly from the North Caucasus Turkmen among whom he lived and taught for several years, and was translated into Russian not by him but by members of that community themselves (Volodin Reference Volodin1908a, 1). This century and more of Russian-, Turkish- and Turkmen-language scholarship on the North Caucasus Turkmen community has barely been acknowledged by Euro-Atlantic scholars, much less incorporated into their own studies of Turkmen identity, the Turkmen diaspora, and the comparative study of language, literature, linguistics, conflict, coexistence, and diasporas in general across Central Eurasia and beyond, which is the subject of the next section.

Figure 4. Abdula Adzhi and his extended family in Kucherla, Stavropol’ Province, 1902. (Photograph by G. Kanevskii. A. Volodin, “Trukhmenskaia step’ i trukhmeny,” Sbornik materialov dlia opisaniia mestnostei i plemen Kavkaza 38 [1908], Otdiel I, second subsection, opposite p. 30.)

Figure 5. The beginning of a North Caucasus Turkmen song about Kirat, the legendary winged horse of the Turkic folk hero Köroğlu. (Image from A. Volodin, “Iz trukhmenskoi narodnoi poezii,” Sbornik materialov dlia opisaniia mestnostei i plemen Kavkaza 38 [1908], Otdiel II, final subsection, 49.)

The Possibilities of Particularity

At this point in the article it would probably be wise to reiterate that the reason I am arguing so forcefully for the importance of North Caucasus Turkmen publications is not because they are particularly profound, informative, or incisive. Given our extremely limited access to them at the present time, it is impossible to say. Nor is it my role, as a librarian, to pass judgment on their worth as literary, sociological, or historical texts. I am arguing for their importance because they are representative of thousands of other numerically small groups, both diasporic and indigenous, whose experiences, traditions, language, and history, as reflected in their own vernacular-language publications, have something to tell us about the human condition. In particular, groups like the Turkmen of the North Caucasus have something to tell us about the nature of national identity, especially along the troubled and geopolitically significant periphery of Central Eurasia.

There are many small and somewhat-isolated ethnolinguistic communities around the world whose connections to larger polities, ethnicities, and identities are clear, and like the North Caucasus Turkmen, they, too, tend to be ignored in Euro-Atlantic scholarship. A few examples from Eurasia will be briefly explored by way of illustration. Firstly, the ancient Pontic Greek communities of the Black Sea region, and, after significant waves of emigration in the 20th century, of Greece itself, also have their own publication history (Akopian Reference Akopian2012), providing interesting perspectives on questions of Greek ethnolinguistic and national identity. These questions have been the subject of countless scholarly works in multiple Euro-Atlantic languages, but almost all of them deal with Greek identity in the context of Greece itself, or with (non-Pontic) Greek identity in nearby areas of Anatolia under the Ottoman Empire. A search for the keyword “pontic” in Historical Abstracts, for example, yields only 35 results out of over 1.2 million in the database, and of these 35, only about 15 actually deal in some way with the Pontic Greeks (with the remainder employing the word “Pontic” to refer to the Black Sea region as a whole). A search for “pontic” and “greek(s)” in the title or abstract of the two million English-language dissertations in ProQuest’s Dissertations & Theses database yields only 20 results, many of them dealing with Greek antiquity.

Secondly, about 200 miles southeast of the North Caucasus Turkmen lies the historic homeland of the Chechens and Ingush, who constitute the North Caucasus’s most populous linguistic subgroup. Chechen and Ingush dominate the Nakh branch of the Nakh-Daghestani language family and are spoken by over 1.5 million people as of 2020. Virtually no Euro-Atlantic scholars are able to read Chechen or Ingush, however, such that even the modest proliferation of Euro-Atlantic scholarly works inspired by the Russo-Chechen wars of the 1990s and their aftermath rely almost exclusively on secondary sources in Russian and other languages. This is particularly unfortunate given the availability of thousands of recent Chechen-language news articles at, for example, Marsho Radio (Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty 2020), of catalogs of over 4,000 Chechen- and Ingush-language works held at the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg (Rossiiskaia Natsional’naia Biblioteka 1998a, 1997a), and other vernacular-language resources in Euro-Atlantic libraries. There is even a bibliography for the handful of works produced by Chechens and Ingush in exile in Kyrgyzstan in the early 1950s (Sergievskaia, Tantasheva, and Saatova Reference Sergievskaia, Tantasheva and Saatova1962), after Stalin ordered the complete ethnic cleansing of Chechnya and Ingushetia in 1944 amid accusations of collaboration with the Nazis. The small communities of Chechens, Ingush, and other peoples of the North Caucasus who were deported in 1943-44 that still exist in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, however, like the North Caucasus Turkmen, are almost completely absent from Euro-Atlantic scholarship. Of the approximately 1,000 articles and book chapters in Index Islamicus about the Chechens, for example, only five appear to focus on the Chechen diaspora in Central Asia.

Finally, the North Caucasus Turkmen newspapers Lenin baýdagy and Güneş have analogues elsewhere that suggest how small periodical publications issued at the geographic fringes of the communities they serve can shed light on several important phenomena. The first Armenian-language newspaper, Azdarar, for example, was published not in Istanbul, Yerevan, or Venice but by the tiny Armenian diaspora community of Madras (modern Chennai, India) between 1794 and 1796. Azdarar has sparked a wide range of scholarly analysis in Armenian, Russian, English, and other languages (Aslanian Reference Aslanian2014; Irazek and Ghukasyan Reference Irazek and Ghukasyan1986; Khachatrian Reference Khachatrian1984). Another significant newspaper published at the farthest edge of an ethnoreligious community is Sibiriya, the early-20th-century newspaper of the approximately 1,500 Muslims then living in Tomsk, in central Siberia. Stéphane Dudoignon (Reference Dudoignon2000) argues that despite Sibiriya’s origins on the periphery of the Islamic world, it is still significant for questions of Muslim identity within the Russian Empire and is, perhaps, even more significant because the very existence of such a newspaper is unexpected. Based on these examples, Lenin baýdagy and Güneş may be able to play a similar role in illuminating aspects of Turkmen identity.

The publications of diaspora communities like the North Caucasus Turkmen raise a number of important questions. What, for example, do Soviet-era Pontic Greek publications and Chechen- and Ingush-language works published in exile in Kyrgyzstan in the early 1950s tell us about Greek, Chechen, and Ingush identity, respectively? Most questions such as these have yet to be answered or even asked in Euro-Atlantic scholarship, despite the obvious truth that diaspora communities produce important cultural and historical artifacts, and not only via their publishing activity. In many ways, Euro-Atlantic scholarship on these groups, as well as the North Caucasus Turkmen, is in its infancy, and the more such groups are left out of our accounts of human history, literature, language, culture, society, politics, economics, religion, daily life, psychology, and identity formation, the more impoverished those accounts become. And meanwhile, despite (in many cases) centuries of success in maintaining a distinct identity connected to a nearby or distant homeland, the continued existence of small communities like the North Caucasus Turkmen is far from assured.

Euro-Atlantic studies of a wide range of phenomena are, therefore, impoverished and even seriously compromised by exclusion–not of one small diaspora community in the North Caucasus, but of all manner of small communities that have evaded sustained, or even desultory, scholarly attention for a wide variety of reasons. I use the term “impoverishment” deliberately to echo the work of comparative literary scholar Rebecca Gould (Reference Gould2016, 24; Reference Gould2013) on the strikingly multilingual literature of the North Caucasus, which she correctly claims is ill-served by a focus only on languages that a certain critical number of Euro-Atlantic scholars can read—which, in the case of the North Caucasus, is hardly any languages at all, unless one counts the rich corpus of Arabic-language materials produced in pre-Soviet and Soviet Daghestan (Kemper Reference Kemper, Companjen, Maracz and Versteegh2010; Shikhaliev Reference Alikberov and Bobrovnikov2010; Shikhsaidov, Kemper, and Bustanov Reference Shikhsaidov, Kemper and Bustanov2012). These Arabic materials, too, are an excellent illustration of the phenomenon wherein a substantial body of primary sources, which have already been interpreted and evaluated in an equally substantial body of secondary (Genko Reference Genko1941; Navruzov Reference Navruzov2011) and tertiary (Osmanova Reference Osmanova2008)Footnote 33 sources written in languages that are also relatively accessible to Euro-Atlantic scholars—Russian and Turkish, in this case—are roundly ignored in North America and Western Europe (Condill, forthcoming). Just as it is hard to imagine a justification for the exclusion of the Arabophone culture, literature, and scholarship of the North Caucasus from consideration alongside all of the other Arabophone traditions in existence from Morocco to Oman, it is hard to imagine a justification for excluding the North Caucasus Turkmen (and the Turkmen of Iran and Afghanistan even more so) from a comprehensive consideration of Turkmen identity. Furthermore, the fact that these perspectives have effectively been excluded from Euro-Atlantic scholarship so far makes them even more valuable, since every contention and characterization that has been made to date can now be tested against new data.

What I am advocating for is the proliferation of studies such as David Brophy’s Uyghur Nation (Reference Brophy2016), which traces the impact of Uyghurs who lived and worked in the Russian Empire/Soviet Union on the social, cultural, political, intellectual, religious, and economic life of Uyghurs in Uyghurstan (Xinjiang) itself. A significant increase in studies such as Brophy’s would not only justify the acquisition of new materials from marginalized communities by Euro-Atlantic research libraries, but also be made much more feasible and successful by libraries’ efforts to build those same collections. James Meyer’s (Reference Meyer2014) account of the lives and influence of the trans-imperial Turkic activists Yusuf Akçura, Ahmet Ağaoğlu, and Ismail Gasprinski also falls into the same category, along with Sean Roberts’s (Reference Roberts1998) article on the long-standing connections among Uyghurs on both sides of the Kazakh-Chinese border.

But it is Brophy that may suggest the most intriguing approaches to studying the North Caucasus Turkmen and their place as simultaneous members of the Turkmen diaspora, of the Turkmen nation, and of the multiethnic North Caucasus. Like Brophy’s swirling concatenation of Uyghurs, Uzbeks, Kazakhs, Tatars, and others moving across shifting borders at the edges of empires, the diverse, complex, and highly interconnected milieu of the North Caucasus highlights the important role that can be played by members of small communities far from traditional centers of power and influence. Both Brophy’s protagonists and the North Caucasus Turkmen were, and are, part of a cross-pollination of ideas, influence, finance, and forms of legitimacy between various segments of what can be seen as a single community spread across multiple polities.

Euro-Atlantic scholarship would benefit from works like Brophy’s and Meyer’s for many more border regions, for many more diaspora communities, and for the people, ideas, and resources that circulate between them and the homeland. Figures like Tumaýylow can provide significant insights into how diaspora communities perceive themselves, and how they are perceived, in turn, from the perspective of the homeland. As a North Caucasus Turkmen in the immediate aftermath of the Russian Revolution, Tumaýylow, unlike so many of his politically active counterparts from neighboring ethnic groups, gravitated toward Aşgabat rather than toward Stavropol’, Makhachkala, or Vladikavkaz, and once he got there, he quickly rose to the highest echelons of the Soviet administration. Even though he belonged to a community that had existed in the North Caucasus for nearly three centuries, Tumaýylow obviously still considered himself a Turkmen, and he was considered to be one by the party apparatus in Aşgabat as well. Comparisons between him and the North Caucasus Turkmen who stayed at home and pursued other options—including anti-Soviet ones—would be instructive and would provide an excellent test case for contentions about Turkmen identity made by Edgar, Clement, Frank, and others. But the broader significance of figures like Tumaýylow, who moved from the margins of his imagined community to its very epicenter and, once there, became caught up in globally significant political affairs originating thousands of miles away, is that they indicate the existence of thousands of other Tumaýylows around the world—people whose lives, works, ideas, and legacies, while perhaps less dramatic than Tumaýylow’s, are no less revealing in terms of the nature and consequences of national and ethnic identity and how they are conceptualized in different contexts. And far from being less valuable because they originate on the margins, stories like Tumaýylow’s have the potential to validate or upend current concepts of identity.

The evidence—Turkmenets Stavropol’skii, Tumaýylow’s missing magnum opus, Gyz beruw, Lenin Baýdagy, Stavropoldan salam, Güneş, and other publications and phenomena—shows that even the North Caucasus’s tiny slice of the millions-strong Turkmen diaspora has much to contribute to our understanding of Turkmen identity. Surely Clement’s observation, for example, that “literacy, language and learning contributed centrally to the development of Turkmen national identity” (Reference Clement2018, 173), should be tested against the apparent strength of Turkmen identity in the North Caucasus, far from the committees, schools, primers, and other markers of identity that flourished across the Caspian Sea in the early Soviet era. Perhaps Frank’s argument that a strong, specifically Turkmen identity pre-dated both the Russian Revolution and Jadid-inspired educational reforms (Frank Reference Frank2020, 306–307) would find corroboration in the North Caucasus. And surely the Turkmen of the North Caucasus and their publications could provide a means to confirm, challenge, or refine Edgar’s assertion that “a Turkmen national identity emerged through a dynamic process of interaction between Bolshevik and Turkmen ideas and practices” (Reference Edgar2004, 262). The North Caucasus Turkmen, given their physical and political distance from Aşgabat, would also serve as an excellent entry point for investigations of Isaacs and Polese’s (Reference Isaacs and Polese2015) “real” versus “imagined” national identity.

The forces that caused the Turkmen of the North Caucasus to commission a Russian naval destroyer in 1905, that drew Tumaýylow to Aşgabat and to a leading role in Turkmen political affairs in the 1920s, that created a Turkmen National District in Stavropol’ Krai in 1925, that caused Hajynazar Jumanýyazow to write a Turkmen-language play and get it published in Moscow in 1928, that made a Turkmen-language newspaper in Letniaia Stavka possible in the 1930s, that drew Sapar Kürenow to do research in the North Caucasus in the 1960s, that motivated Jumahaset Ylýasow to publish his book of poems in Aşgabat in 1994, and that once again facilitated the publication of a Turkmen-language newspaper in the North Caucasus in the 1990s and 2000s all speak to a powerful sense of Turkmen identity despite centuries of separation from Turkmenistan proper—a sense of identity that may not be fully explained or explainable by the available Euro-Atlantic scholarship on Turkmen identity.

A complete analysis of the forms that Turkmen identity has taken in the unique conditions of the North Caucasus will have to wait for access to Tumaýylow’s magnum opus, Gyz beruw and other early Soviet plays, and Lenin baýdagy and Güneş, but this much seems clear: Turkmen identity, the role of diaspora populations, and the borders and contours of identity in general are more complicated than Euro-Atlantic scholarship and Euro-Atlantic library collections have been able to express so far. Taking a microscope to one small portion of the Turkmen diaspora can serve as a step in the right direction.

Yet, once again, it must be conceded that the entire content of the vernacular-language North Caucasus Turkmen sources whose existence is painstakingly unearthed or tantalizingly hinted at in this article may not be enough to launch a monograph or a dissertation on the North Caucasus Turkmen. Perhaps they only deserve a footnote, or a shrug. But even if that is true, it is still important to make arguments from the margins in this way, because they throw everything else into sharp relief. If the North Caucasus Turkmen have not published enough, or are not numerous enough, or are not important or interesting enough to justify or warrant a serious scholarly treatment in the Euro-Atlantic world, then what about the neighboring Nogais, whose ancestors established a significant late-medieval polity (the Nogai Horde), who have over 1,500 works published in their language held at the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg, and who today are 100,000 strong and live all over the North Caucasus? Are their vernacular-language works worthy of study by Euro-Atlantic scholars, or not? If not the Nogai, what about the Kumyks, from whose ranks many of Daghestan’s most prominent leaders, scholars, educators, and authors have been drawn, who have over 3,000 vernacular-language published works dating back to 1883 held at the Russian National Library, and who currently number over 500,000? What about the Lezgis of southern Dagestan and northern Azerbaijan, with over 2,500 works at the Russian National Library and a population as high as one million (Rossiiskaia Natsional’naia Biblioteka 1997c, 1998b, 1997b)? At what point does it become imperative for Euro-Atlantic scholars to acquire the necessary language skills to engage with a corpus of material of this size? How many articles, books, and dissertations based on vernacular-language materials does a given ethnic group “deserve”? Should the answer depend on the relative difficulty (or ease) of learning their language for English speakers? Should it depend on whether Euro-Atlantic libraries already have strong collections of materials in that language?

Perhaps the exclusion, thus far, of the North Caucasus Turkmen or of any single one of the thousands of similarly marginalized groups around the world from the Euro-Atlantic scholarly record is not too tragic in terms of the advancement of human knowledge, which, historically, has been gradual, fitful, and liable to experience setbacks and reversals in any case. But surely a highly developed, centuries-old, massively multiethnic society of approximately 7 million indigenous people existing in a geopolitically significant and conflict-prone region the size of the US state of South Dakota (i.e., the North Caucasus as of 2020) is worthy of study as a system or a totality, and the study of that totality is impoverished by the exclusion or neglect of any one group within it. When taken together, the extraordinary diversity of the peoples of the North Caucasus presents a nearly unique situation in human history, begging the question of why this region is so under-studied in the Euro-Atlantic world.Footnote 34 Yes, the languages are difficult; yes, the published and unpublished materials are hard to access and acquire; yes, the alphabets have changed many times over the last 150 years; yes, it has been dangerous and sometimes impossible to do fieldwork there for many decades. But the secondary sources are plentiful; they are largely written in languages (Russian and Turkish) that Euro-Atlantic scholars have every opportunity to learn; and the difficulties associated with transliteration, general lack of awareness, and poor Euro-Atlantic library collections are ultimately unnecessary, and can be overcome with a modicum of collective effort.

In other words, the scholarly significance of the North Caucasus as a region is greater than the sum of its parts and cuts across many disciplines. It provides fertile ground for comparative studies of many kinds and provides an opportunity for Euro-Atlantic libraries to play a major role in cultural and linguistic preservation efforts. The Turkmen of the North Caucasus present an ideal test case for a wide variety of research propositions. Surely the theories advanced to explain nationalism and national identity in Indonesia, Egypt, Argentina, Uzbekistan and elsewhere can productively and provocatively be tested against the national sentiment, or lack thereof, among groups like the North Caucasus Turkmen. They can provide insight into larger questions, such as why the Turkmen state has been so ambivalent about its relations with Turkmen populations directly across its borders, and why there has been essentially no self-determination or pan-Turkmenist movement among the Turkmen of Iran and Afghanistan, even as the latter country has existed in a state of profound fragmentation for decades. Also, since the Turkmen (or “Turkmen”) of Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Iran, Afghanistan, China, Iraq, Turkey, Syria, and Russia live under a wide variety of authoritarian regimes of differing intensities, goals, and experiences of recent or not-so-recent violent conflict, perhaps they can tell us something about adaptation, the persistence and mutability of identity, and authoritarianism itself.

In addition, what can the North Caucasus Turkmen, whose history is so intimately intertwined with their neighbors the Kalmyks, tell us about the aftermath of ethnic cleansing, given that the Kalmyks were deported to Siberia as supposed Nazi collaborators in 1944 while the North Caucasus Turkmen were not? What about the other Turkic peoples of the North Caucasus that were deported, the Karachais and Balkars who lived 150 miles away near the base of Mt. Elbrus? What about the experience of the North Caucasus Turkmen under Nazi occupation in late 1942? What about the position of the North Caucasus Turkmen as a link between the sedentary populations to their south and the nomadic world to their north, which stretches around the northern edge of the Caspian Sea and all the way to Iran, Mongolia, and beyond? What about the fact that the North Caucasus Turkmen, with their various linkages to other Turkmen in Turkmenistan and elsewhere, are simultaneously enmeshed in the remarkable ethnolinguistic diversity of the North Caucasus itself,Footnote 35 with its history of violence, resistance, insurgency, and conflict, but also of coexistence, solidarity, multilingualism, pluralism, and the preservation of the languages, cultures and traditions of tiny ethnic groups over many millennia? While many of the ethnolinguistic groups of the North Caucasus have large diasporas in the Middle East and elsewhere, what about the fact that the Turkmen are almost unique in that their coethnics in Turkmenistan proper are also the titular ethnicity of a sovereign state?Footnote 36

Despite all these possible avenues for research, the combined neglect of scholars and librarians has effectively erased the Turkmen of the North Caucasus from existence in the Euro-Atlantic world. If we do not write them and the thousands of other groups like them back in, our understanding of the human experience will be diminished, perhaps forever.Footnote 37 The great library collections of the Euro-Atlantic world have been and continue to be shaped by thousands of small collection-development decisions. While these decisions may seem inconsequential at the time, they can end up influencing the course of Euro-Atlantic scholarship in profound ways. When we librarians fail to do due diligence on the areas that we cover, when we fail to continually reimagine our collections, when we fail to challenge ourselves, our staff, and, most importantly, our administrators, when we fail to pursue projects or goals that are difficult to achieve, then scholarship as a whole suffers, and libraries’ role as collectors and protectors of the common cultural heritage of humankind is not fulfilled. We should not accept statements like Wixman’s at face value. We should not rely on vendors whose motivations are different than our own to seal the fate of groups like the Turkmen of the North Caucasus, Pontic Greeks, and Chechens and Ingush in Central Asia forevermore. We should not allow our collections to become impoverished because “no one on our campus at the moment reads this language or alphabet” or because “no one is currently teaching a course on this country/people/region.”

With that kind of short-sighted thinking, our understanding of the world—through, in this case, our understanding of Turkmen identity—will ultimately become impoverished as well.

To evaluate blanket statements about the (non)existence of potential library materials, to uncover previously unknown sources, to expand our picture of human knowledge and human endeavor and the comprehensiveness of the permanent record thereof in the world’s libraries: these things are arguably the essence of a librarian’s job. If there are North Caucasus Turkmen newspapers, plays, and poetry out there that even Ýazberdiýew failed to identify as such, what else are Euro-Atlantic libraries missing, and how will the scholarship and worldview of future generations be shaped or impoverished as a result?

Acknowledgments

I would like to take this opportunity to thank the Interlibrary Loan Department at the Library of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and in particular Kathy Danner and Alissa Marcum, for supplying hundreds of obscure sources that I needed for the present article and for the broader research that underlies it. I would also like to thank my family, and especially my wife Emily, for their love and support, and for giving me the many, many evening and weekend hours I needed in order to complete this project.

Disclosures

Author has nothing to disclose.

Financial Support

This work was supported in part by the Research and Publication Committee of the Library of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and by the Library’s Ralph T. Fisher Professorship Fund.