This chapter sets out some of the complexities and strategies regarding processes of decolonizing literary pedagogies in two proximate sites of the Global South: Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. In this project, I advocate an intersectional approach and method that defetishizes the literary object and enables students to engage with various forms of literary creativity in their varied and shifting positions within place, history, and culture. Ben Etherington and Jarad Zimbler argue:

A decolonized literary studies does not come off-the-peg, and making decisions about what or who we read requires that we think concertedly about the colonial legacies and entanglements of particular places and literary communities at particular historical junctures. It requires, in other words, that we think seriously about what exactly “context” means.

So, too, as Wiradjuri1 writer, teacher and academic Jeanine Leane writes, “history and literature are inseparable” (Reference Leane, Birns, Moore and ShieffLeane, “Aboriginal Literature” 238) and, as Samoan writer Albert Wendt claims, “all creative writers are historians” Reference Wendt(“Insider” 6, quoted and discussed in Reference SharradSharrad, “Albert Wendt”). Accordingly, the ensuing discussion devotes a great deal of space to particularities of “context” and moves between specific and shared experiences of Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand and includes some comparison. This essay was researched and written on the unceded, sovereign lands of the Bedegal people of the Eora Nation of what is also called Sydney, Australia. In this project, I have consulted First Nations writers and academics from both countries and, amongst a range of responses, I have met with some (depersonalized) resistance to my authorship of this chapter around issues of the ongoing authority accorded and exercised by non-Indigenous academics. I am a senior settler academic in a country, Australia, that only recognized the citizenship of its First Nations peoples in 1967 and which is only now debating whether the constitution should include recognition of First Nations primacy.2 Also, I am neither a Māori nor a Pākehā3 (European non-Māori) citizen of Aotearoa New Zealand so there are colonizing issues about me speaking of that context. This occurs in a long history of Australia commandeering debate in the Australasian context. The issue of decolonization, including the decolonization of literary pedagogies, is immediate, fraught, and painful in both places.

The points of connection and distinctiveness between Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand are clarifying relative to broad issues of decolonizing literary pedagogies as well as each of these two places. The key sites of these correlations and divergences concern their respective First Nations peoples, their particular British colonial histories, positions in the (colonized) region, scales of territory and population, the patterns of regional and global immigration, and their attendant demographics and literatures. Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand are close neighbors, and the bonds between them are deep, but they are also relatively recent. There was no relationship between the First Nations peoples of the two territories before British colonization, and they became more distant when the colonial structure of “Australasia” – which embraced the many British colonies in Oceania – was dismantled in 1901 when Australia federated to become a nation state (Reference DenoonDenoon).

There has been little critical work on the literatures of both places. If they are grouped together at all, it is most often for bibliographic purposes, and from distant perspectives they seem to appear as a kind of duo. However, the actual links have been tenuous. In 2012, a proposal to expand the Association for the Study of Australian Literature (ASAL) to include the literature of Aotearoa New Zealand – where there is no equivalent scholarly society – was rejected by the Australian members (Reference BrennanBrennan). The reasons for this decision were largely nationalist and partly logistical. There was also the view that the South Pacific Association for Commonwealth Literature and Language Studies (SPACLALS) fulfilled this function.4 Resistance also reflected an anxiety connected to being a largely invisible national literature of the Global South at a time when the category of national literatures was contested (Reference DixonDixon, “National Literatures”). At this time, Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand were encountering new – and ongoing – threats to copyright law that would decimate local publishing houses, which are vital to literary cultures in both places (Loukakis; Reference NagleNagle). Finally, wider Australian culture including government, does not display much interest or support for its literary cultures (Reference MeyrickMeyrick). So there was an understandable motivation to protect ASAL from diffusion or increased opacity.

Nonetheless, in the view of this author, the decision not to expand the Association to include Aotearoa New Zealand was a missed opportunity that significantly slowed the pace of the decolonization of literary research and pedagogies in Australia, and perhaps Aotearoa New Zealand as well. In particular, it would have provided a forum for the First Nations peoples of both places, who have too often been in radical minority in such organizations, and it would have meaningfully complicated the power binary of the First Nations and settler cultures in each place. Moreover, ASAL missed the opportunity to provide this intellectual space and undertake the education and critique this process would have required.

Over the past decade, there has been increased contact between the First Nations writers of both places, including the biannual conventions of the First Nations Australia Writers Network (FNAWN) from 2013 (First Nations Australia Writers Network), in artistic practices such as Spoken Word Poetry, and in collections such as Sold Air (Reference Stavanger and Te WhiuStavanger and Te Whiu). I note also that Black Marks on the White Page, a collection of “Oceanic stories for the twenty-first century,” edited by Witi Ihimaera and Tina Makereti, includes work from Wanyi Australian writer Alexis Wright, as the editors extend the category of the Pacific to its furthest western point in an explicit gesture of inclusion of Australia’s First Nations.

These connections are an inchoate force gaining momentum. So, too, as Alice Te Punga Somerville recently showed, these links are not new (Reference Te Punga SomervilleTe Punga Somerville). In “Reading as Cousins: Indigenous Texts, Pacific Bookshelves,” Te Punga Somerville focuses on an “impossible photograph” that shows First Nations writer and activist Oodgeroo Noonuccal with Pasifika writers at the 1980 SPACLALS conference. SPACLALS, structured by the comparative practices of postcolonialism, now has far fewer members – there are far fewer academic staff in English literary studies – and the upsurge of First Nations activism and literatures in the last three decades has focused attention on the redress of specific histories. However, perusal of the programs of mainstream writers’ festivals in either place over the last decade shows very little interaction or interest in either settler culture or First Nations writers between neighbors, with both countries preferring to select their international guests from farther afield rather than connecting with their own region.5

As this lack of interaction suggests, Australians and Aotearoa New Zealanders have a poor record of reading and teaching each other’s literature. This is, in large part, a legacy of colonial publishing structures, by which books were generally published in Britain until the mid-twentieth century. Most Australians would not ever have read any literature of Aotearoa New Zealand and vice versa.6 There have been very few exceptions to this mutual and structural aversion. Its most visible exception, Lydia Wevers, describes the situation: “I am an Aotearoa New Zealand reader of Australian literature. That makes me just about a category of one. The reverse category, an Australian reader of Aotearoa New Zealand literature, is also a rare beast, though perhaps there is a breeding pair in existence” (Reference Wevers“The View from Here” 1). Wevers made this observation in her keynote address at the 2008 conference of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature (ASAL), an annual event she traveled across the Tasman Sea to attend for two decades – the only Aotearoa New Zealander to do so.

Australian First Nations writers and critics lead the decolonization of Australian literary studies and include the highly influential interventions of The First Nations Writers Network, Jeanine Leane, Kim Scott, Alexis Wright, Ali Cobby Eckermann, Lionel Fogarty, Jim Everett, Melissa Lucashenko, Evelyn Araluen, and Yvette Holt amongst many others. Wevers’s perspective as a non-Australian and as Pākehā New Zealander also assisted in patterning modes of decolonization for Australian literary studies through comparison of the two contexts. She achieved this by her persistent and productive criticism of Australian scholarship’s unconscious colonialism. Her 2006 essay, “Being Pakeha: The Politics of Location” provided a model for theorizing localized complexities and responsibilities of settler-culture standpoint (Reference WeversWevers, “Being Pakeha”). She also convened the 2012 annual ASAL conference in Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand – the only ASAL conference ever held offshore – where Australian delegates encountered the standard protocols of Māori recognition, including the extensive welcome onto the Te Herenga Waka Marae (Victoria University’s tribal meeting ground), which went far beyond the tokenism of Australian settler-culture practices of the time. Wevers understood her position as the director of the Stout Research Centre for New Zealand Studies at Wellington University as an opportunity to effect decolonizing change and expected or imagined that we Australians shared that objective.7 Her influence alone is evidence of the potential benefits of trans-Tasman interaction regarding the decolonization of literary studies in the region.

There has been some change. The Association of the Australian University Heads of English (AUHE), the peak body for university English education and research, amended its mission statement in 2021 to identify the necessity of “decolonising and indigenising the field of English education and research” and harvests information and strategies from across the country for use in teaching and research (“Mission Statement”). In 2022, all keynote papers at the ASAL conference were given by First Nations writers and critics from across Australia and from Aotearoa New Zealand. So, too, the conference was framed by local community members from nipaluna/Hobart and palawa writers from lutrawita/Tasmania, and many of the conference sessions were focused on the decolonization of Australian literary studies including research, curricula, and pedagogies (“Coming to Terms”). Of course, these shifts do not signal the achievement of a decolonized field, but they do mark a significant moment in the process of decolonizing literary studies research and teaching.

This mutual ignorance of Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand’s literature is true also of educational institutions where, with only a couple of exceptions, neither place teaches the literature of the other. In researching this chapter, I located one course in Aotearoa New Zealand that includes Australian literature (Victoria University, Wellington, which was originally set up by Wevers) and one course in Australia (University of Adelaide), framed as a “Trans-Tasman” study, which engages with the literatures of both places as an interaction. One other, Australia and Oceania in Literature (University of New England), conceives of these literatures regionally. The Postcolonial Literatures course at my own university, the University of New South Wales (UNSW Sydney), opens with the verse novel Ruby Moonlight by Yankunytjatjara/Kokatha poet Ali Cobby Eckermann. It is a first-contact narrative set in mid-north South Australia in the 1880s. The course also includes a module that groups together Pacific, Aotearoa New Zealand, and Australian literatures relative to First Nations Spoken Word poetry. If there are any more courses in either country, they are well hidden. It is more common for the postcolonial courses in each place to develop curricula that span diverse and far-flung contexts of the former empire: Africa, South Asia, Canada, the Caribbean. Moreover, when Aotearoa New Zealand thinks regionally in this context it is far more commonly in relation to its Pacific neighbors rather than Australia. The main reason for this is the deep connections between Pasifika peoples and Māori and the number of Pasifika people settled in Aotearoa New Zealand.8 Aotearoa New Zealand is a Pacific country with a Pacific history, populations, and imaginary. Australia is not, though the state of Queensland in northeastern Australia has some strong identifications.9 There are increasing numbers of Pasifika peoples migrating to Australia permanently or on extended fly-in–fly-out working visas, but Australia’s imaginaries are of the interior and the littoral. When Australia federated in 1901 and separated from Britain’s other Pacific colonies, it become more insular in this respect (Denoon; Perera; McMahon, “Gilded Cage”; Reference McMahonMcMahon, “Encapsulated Space”).

Both Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand are what Alan Lawson first termed “second world” societies, so named to emphasize their “secondariness” and “second-ness.” They share, with Canada and South Africa, the ambiguous status of being “both imperialised and colonising” (Reference LawsonLawson).10 Together with Canada – but not South Africa – these second-world settler cultures now constitute significant majorities of the populations of each place. Australia’s population as at 31 December 2021 was 25,766,605. Of this number, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people represent 3.2% of the population; 26% of the population were born overseas, and Aotearoa New Zealanders ranked as the fourth-highest immigrant group. As of March 2022, the population of Aotearoa New Zealand was 5,124,100, of which 17.1% are Māori and a further 8.1% are Pasifika (“New Zealand Country Brief”). Just over 27% of the population of Aotearoa New Zealand were born overseas, and Australians have historically comprised one of the top three immigrant groups.11

The development of literary studies as part of the expansion of Australian universities is clarified by Catherine Manathunga’s 2016 comparative study, “The Role of Universities in Nation-Building in 1950s Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand.” Manathunga identifies three major differences between the two reports commissioned by Australia (1957) and Aotearoa New Zealand (1959) respectively to assess the need for the expansion of their university sectors. Manathunga’s first finding underscores the well-known difference in attitudes to Britain. As a former penal colony, one of the ur-narratives of settler Australia is the need to cut ties with the “mother country.” Accordingly, the Australian report included little about British universities. The Aotearoa New Zealand report, on the other hand, based its recommendations on a British educational ideal. The second finding points to the greater gender bias of Australia – no surprises there. Australia has a long history of settler-culture misogyny.12 The third issue relates to the composition of disciplines and faculties. The Aotearoa New Zealand report considers the modern university in terms of cultural benefit, which it links institutionally to the arts and humanities. The Australian recommendations, on the other hand, in keeping with mainstream Australia’s ongoing suspicion of the arts, view the arts and humanities as addenda for the main business of science and technology.13 The three distinctions Manathunga identifies in the reports of the 1950s may well still hold in 2022, especially in relation to the respective institutional commitments to cultural benefit.

In 2023, policies of the governing bodies of Australian and Aotearoa New Zealand universities, Universities Australia and Universities New Zealand – Te Pōkai Tara respectively, indicate that Australia lags behind its neighbor in many aspects of decolonizing policies including literary pedagogies.14 While not fully accounting for this lag, it is true that Australia is a much larger and more complex context: it has forty-three universities, spread over a vast continent that is homeland to 250 First Nations with as many languages. Its population is also far more multicultural. Aotearoa New Zealand has eight universities that cover the two main islands which are home to thirty-five Iwi (Māori community) groups, who, with variations, share(d) the same language, te reo Māori. This small number of universities and the shared understanding of te reo Māori has enabled Universities New Zealand – Te Pōkai Tara to implement the “Te Kāhui Amokura Strategic Work Plan” across all universities in the country.

However, even with the differences of scale and diversity noted, Universities Australia’s actions regarding the decolonization of governance, research, and pedagogy are long overdue, which it admits in its Indigenous Strategy Paper 2022–2025. As with Aotearoa New Zealand, several Australian universities have now appointed First Nations deputy vice chancellors or pro vice chancellors onto their senior leadership teams. Most universities now include centers or departments to support First Nations staff and students. Increasingly, these centers also provide training for non-Indigenous staff in how to decolonize their research and pedagogies. My own faculty at UNSW Sydney houses Nura Gili (Place of Fire and Light), the Centre for Indigenous Programs, which devised and designed an extensive, two-stage “Cultural Reflexivity” course, mandated for all academic and professional staff in the faculty in 2021 and 2022. The course, like others across the country, was developed by First Nations staff and students and addresses many issues of pedagogy, including content and delivery, the potential complexities of tutorial discussion, and standpoint theory. Courses such as these across the country undergird current decisions regarding the decolonization of English literary studies and creative writing courses and inform the discussion here (Reference Collins-Gearing and SmithCollins-Gearing, Brooke and Smith).

Colonization to Decolonization

For Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand, the timing and context of their discovery and invasion by the British established “the colonial legacies and entanglements of particular places and literary communities at particular historical junctures” (Reference Etherington and ZimblerEtherington and Zimbler 229). As Paul Sharrad notes, Australia was the last of the “new worlds” discovered by Europeans, bookending the Columban discoveries of the Americas (Reference Sharrad“Countering Encounter”). Australia’s First Nations peoples comprise the oldest continuing culture on earth, having occupied the full land area of 7,692,024 km2 and surrounding waters for approximately 60,000 years. The documentary First Australians describes the 1788 invasion as the event when “the oldest living culture in the world [was] overrun by the world’s greatest empire” (Blackfella Films, 2008). At the time of invasion, there were approximately 250 different First Nations language groups across the country, with many additional dialectical variations (Reference LeaneLeane, “Teaching”). It is estimated that 120 languages were spoken in 2016, and a 2019 study estimated that 90 percent of the languages are endangered.15

The terms of the Australian invasion and occupation were/are unique. As Stuart Macintyre summarizes: “In striking contrast to its practices elsewhere, the British Government took possession of eastern Australia (and later the rest of the continent), by a simple proclamation of sovereignty” (Reference Macintyre34). This occurred according to the Roman law of res nullius, that is, the assessment that the land was not properly owned (cultivated) by the First Nations peoples (Reference FitzmauriceFitzmaurice). The attendant assumption was that the Aboriginal peoples were not sufficiently civilized to enter into trade agreements or treaties. The terms of this proclamation and the denial of Aboriginal sovereignty and humanity continues to ravage Australia, especially its First Nations peoples. This shameful distinction is not widely understood by non-Indigenous peoples in Australia and needs to be discussed in teaching First Nations literatures. As Mununjali Yugambeh poet Ellen van Neerven writes in their poem “Invisible Spears” (Reference Fitzmaurice74):

And so, in their 2020 collection Throat, van Neerven addresses the absence of a treaty in terms of authorship, publication, and reading (62):

The British invasion and usurpation of Australia in 1788 marks the beginning of Britain’s second empire, which paved the way for its “Imperial Century” (1815–1914) (Reference ParsonsParsons). It was motivated by the perceived need to establish a penal colony after the loss of American colonies in 1783. Hence, from the outset, colonies in New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land (now lutrawita/Tasmania) and later Queensland and Western Australia were based on forced migration, harsh conditions, unfree labor, and imprisonment. These beginnings instilled a great and continuing distrust of (British but also general) authority amongst large elements of the settler population, which marks a significant cultural difference between the cultures of Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand.

The First Nations people of Aotearoa New Zealand, the Māori, first settled the country between 1320 and 1350, having navigated the Pacific tides west from Polynesia (Reference Mafile’o and Walsh-TapiataMafile’o and Walsh-Tapiata). This makes Aotearoa New Zealand the youngest country on earth. While English is the lingua franca, te reo Māori was recognized as one of the nation’s two official languages in 1987. There are dialects within te reo Māori, but the one language is understood by Māori speakers across the country. Perhaps the greatest distinction between Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand in terms of decolonizing imperatives is the Treaty of Waitangi. The British colonization of Aotearoa New Zealand, which began in the early nineteenth century, was formalized by the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840, signed by the British Crown and Māori chiefs (rangatira) from Aotearoa New Zealand’s North Island. This agreement, which is bilingual, contains some key differences between the English and te reo Māori versions. It grants governance rights to the Crown while Māori retain full chieftainship of their lands. It also gives Māori full rights and protection as British subjects. However, disagreements regarding the respective claims of sovereignty caused wars and hostility between Māori and Pākehā for the next 150 years. This legacy remains highly problematic.

The Treaty of Waitangi – despite its many problems and ambiguous status – established a contractual relationship between colonizers and colonized that recognized Māori priority and, with contention, ongoing sovereignty. Aotearoa New Zealand was conceived of as a bi-cultural society. This is not to deny the genocidal policies inflicted on Māori. None of the Australian colonies, nor the federated nation of Australia from 1901, have ever developed such treaties. Those Australians who are not Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islanders are, therefore, living on lands that were never ceded to Britain. There have been numerous calls for a treaty in the last three decades (“The Barunga Statement”). The Treaty of Waitangi is often invoked as a possible model for Australia as it negotiates the instantiation of a formal recognition of First Nations’ primacy, called “the Voice,” into the federal constitution (Reference O’SullivanO’Sullivan). This was a charged issue in Australia’s federal election in May 2022, and there may be a national referendum to decide on the Voice in 2023. The Voice is a predicate of decolonizing the Australian polity.

Decolonizing Whiteness

The colonial regimes of both Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand effectively implemented immigration policies to ensure the dominance of White populations. The impact of these policies is still current and a vital issue in the decolonizing of literary studies. The White Australia Policy, formalized at Federation in 1901, was not fully dismantled until 1973, and Australia followed Canada in formally adopting a multicultural policy in 1978, the terms of which constitute a concerted “repudiation” of former policies. Aotearoa New Zealand’s colonial government also implemented policies to ensure White immigration, including legislation that limited Asian immigration and inhibited Asian peoples’ capacity to naturalize as citizens (“Chinese Portraits”). These racist policies have diminished since the 1970s, and many Pasifika peoples in particular have migrated to Aotearoa New Zealand from that time, as well as an increasing number from more diverse homelands. This “Whiteness” excluded all but Anglo-Celts and some northern Europeans. Its legacy also creates tensions between the postcoloniality and multiculturality of these places (Gunew). Any decolonization needs to negotiate this complexity, which is integral to addressing historical and current racism.

Pedagogical Strategy 1: Decolonizing History

The dates of Australian and New Zealand’s colonization coincide, inter alia, with the development of a new historical consciousness in Western thought, including Kant’s thesis on Universal History and Herder’s theory of historical equilibrium, both published in 1784 (Reference KantKant; Reference HerderHerder). The encompassing, advancing sweep of Universal History authorized the “civilizing mission” of colonialism and relegated First Nations peoples to prehistory and/or the genocidal implications of universal progress. Jeanine Leane writes: “I am a creative writer of poetry and prose and am driven to write, as I believe many Aboriginal authors are, because I have always been positioned on the other side of history” (Reference LeaneLeane, “Teaching”). Leane’s guidelines for decolonized and Indigenized pedagogies in Australian literature include addressing the multiple problematics of history.

One of the main strategies Leane advocates is the reinclusion of the histories and experiences of First Nations peoples, whether we are teaching Australian texts by First Nations writers, settler-culture writers, or newer migrant writers. In all these contexts, Leane argues, the continuing presence of First Nations needs to be reinserted.16 When there are no First Nations characters in the fiction or poetry, which is common, she directs us to identify the lands on which the texts are set, immediately identifying the erasures that provide the ground for settler writing. Instancing narratives of the nineteenth-century gold rushes, she asks: “On which Aboriginal lands did the many Australian goldfields lie? Who were the traditional custodians before the lands were mined for profit from which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people never benefitted?” (Reference LeaneLeane, “Teaching” 7). Discussing texts published more recently, Leane directs teachers to “familiarise students with the historical context of the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (1987) and the High Court’s decision on the Mabo case (1992)” (“The Mabo Case”) as crucial historical events in the colonized history of First Nations peoples.

Finally, Leane points out the need to teach the different experiences of colonization across the country. Some areas of the central Australian desert were deemed uninhabitable by Europeans until the 1920s – an irony given that the Arrernte people have lived there for tens of thousands of years. From the 1920s, miners and pastoralists made further ingressions into the Australian continental center, effectively staging a second era of colonization (Reference RobinRobin). This experience contrasts starkly with the experience of the Palawa people of lutruwita (the island state of Tasmania), who were killed en masse in the 1820s and 1830s. Given such a vast land area and so many First Nations peoples, history across Australia is not synchronous or consistent.

A number of the novels of Noongar17 writer Kim Scott engage with archives: both the cultural heritage of the Noongar people and the archives of government records. Scott’s essay, “A Noongar Voice: An Anomalous History,” provides an account of the difficulties and pain of these processes. Specifically, he documents the difficulties of locating any “voice” of First Nations peoples in official records alongside the erasure of Noongar modes of memorializing experience. The latter was accomplished through government policies of cultural destruction, including the removal of children from their families. Hence, he finds a double erasure; there is little history in either archive. However, he persists with both processes and continues to see the value in conventional research for its capacity to affect the present and future: “that was my concern, researching a novel: not what was, but what might have been, and even what might yet be” (Reference ScottScott 103).

One of the most striking aspects of contemporary First Nations writing for non-Indigenous Australians is the manner in which the texts sustain people’s simultaneous histories in the constructions of world and being: the ontologies and deep time of traditional culture and country and those of European modernity and colonization. The decolonizing of Australian literature requires acknowledgment of this complexity, by which First Nations peoples have negotiated two vastly different, even incompatible realities. Chapter 1, “From Time Immemorial,” of Alexis Wright’s award-winning novel Carpentaria (2006) juxtaposes these histories.

A NATION CHANTS, BUT WE KNOW YOUR STORY ALREADY. THE CHURCH BELLS PEAL EVERYWHERE. CHURCH BELLS CALLING THE FAITHFUL TO THE TABERNACLE WHERE THE GATES OF HEAVEN WILL OPEN, BUT NOT FOR THE WICKED. CALLING INNOCENT LITTLE BLACK GIRLS FROM A DISTANT COMMUNITY WHERE THE WHITE DOVE BEARING AN OLIVE BRANCH NEVER LANDS. LITTLE GIRLS WHO COME BACK HOME AFTER CHURCH ON SUNDAY, WHO LOOK AROUND THEMSELVES AT THE HUMAN FALLOUT AND ANNOUNCE MATTER-OF-FACTLY, ARMAGEDDON BEGINS HERE.

And then the text shifts from the time of the nation state to time immemorial: “The ancestral serpent, a creature larger than storm clouds, came down from the stars, laden with its own creative enormity” (1). The collision of these ontologies is intolerable for the traditional owners of the Gulf country, as the narrative starkly rehearses. However, the novel also shows how colonization – a glitch within time immemorial – is comprehended and eclipsed by this deeper history and understanding. Any deficit resides with the settler culture whose understanding is limited to the confinements of Western modernity and World History.

The first published novel by a Māori woman, Patricia Grace’s Mutuwhenua: The Moon Sleeps (1978), follows the narrator’s negotiation of these conflicting histories, temporalities, and their attendant ontologies. Throughout the narrative, Ripeka’s literal touchstone is the shared meaning of a sacred and valuable stone, which she and others find as children and which is returned by her family to the gully of the ancestors as its right and proper place. The collective belief in the rightness of this action organizes the coordinates of time that Ripeka sustains alongside those of White Western New Zealand. Ultimately, she decides that her new baby will not be raised by her and her Pākehā husband but by her extended Māori family. Her husband needs to accept the rightness of what he cannot fully share or understand.

Pedagogical Strategy 2: Decolonizing Literary Histories

In the entanglement of literary and political history, the time of the colonization of Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand also coincides with the publication of the first Bildungsroman, Goethe’s Wilhelm Meister’s Apprenticeship, which was begun in the 1770s and published in 1796 (Reference GoetheGoethe). As Peter Pierce claims, the account of Australia’s literary maturation came to be seen as inseparable from Australia’s political, national maturation according to this literary-historical Bildung (Reference Pierce and Hergenhan82). It is a connection that is rehearsed throughout Australian fiction from the first novel by the convict Henry Savery in 1830 to the present.18 This network of progress narratives affects much if not all of the English literary curriculum but is of particular significance to Australian literature and its literary histories, given the enduring compaction of narratives and events, including colonial invasion and narratives of individual (and corrective penal) transformation.

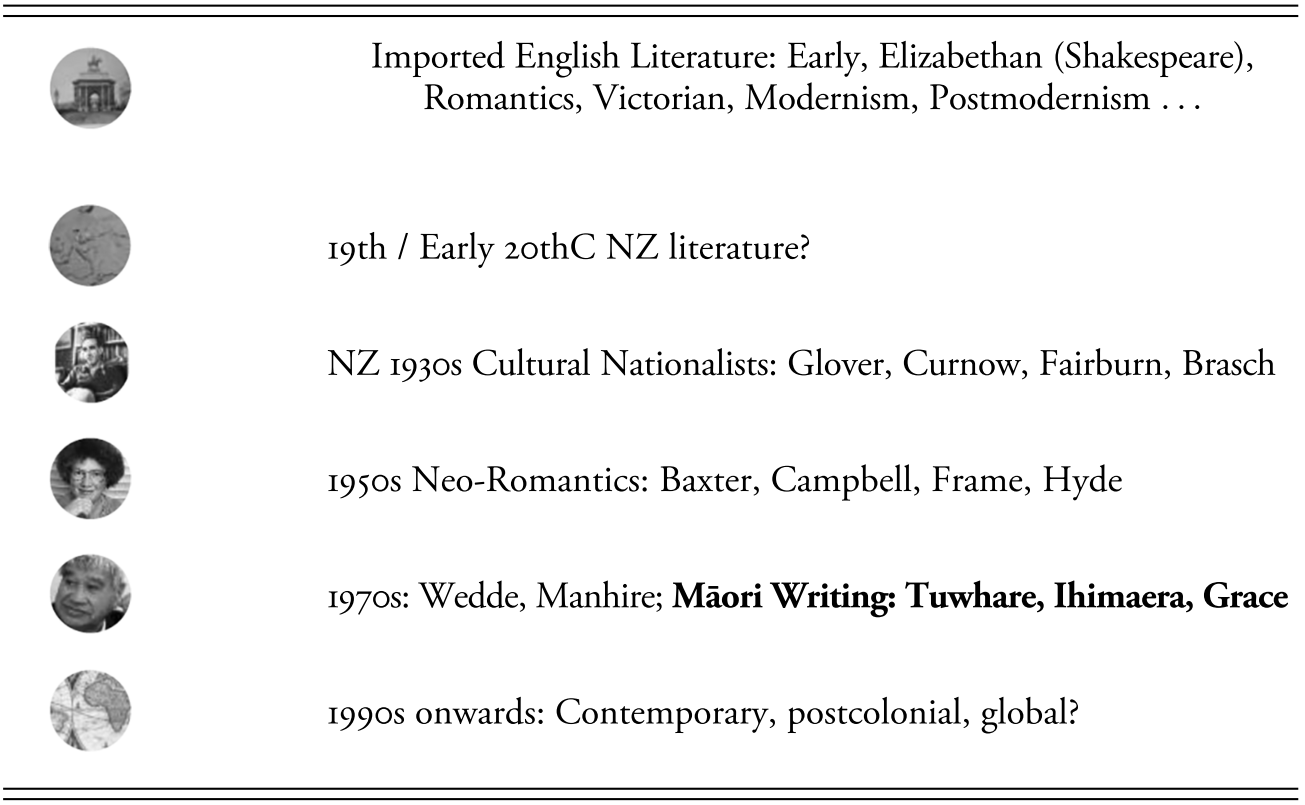

Historically – for the purposes of this discussion, at least – English literary studies in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand can be viewed in four stages. First is the establishment of “English” as part of the broader process of the rise of English literary studies, and as a strategy and effect of British colonialism. The first New Zealand Professor of Classics and English Literature and Language was one of the first three appointments upon the founding of the University of Otago in 1869, Aotearoa New Zealand’s first university. The first Australian Chair of English Literature and Language and Moral Philosophy was created in 1874 when the University of Adelaide was established (Reference DaleDale 42–44). The second stage marks nationalist turns to the settler literatures, or what Robert Dixon refers to as “periods of nation-centrism.” Regarding Australia, Dixon writes:

In Australian literary history, there have been two periods dominated by the epistemology of nation-centrism: the period of Federation, from 1880–1920, and the period from the second world war to the Bicentenary, from 1945 to 1988, when Australian literature was established as a discipline.

This latter period produced many histories of Australian literature, and the first Chair of Australian literature was established at the University of Sydney (1962), in response to public advocacy. (This Chair was not filled after the retirement of Professor Robert Dixon in 2019.) The Association for the Study of Australian Literature was established in 1977, an offshoot of SPACLALS discussed above, “to encourage and stimulate the writing and reading of Australian literature and the study of and research into Australian literature and Australian literary culture.”19

In his 2007 history of Aotearoa New Zealand literature, The Long Forgetting, Patrick Evans recounts the formation of a similar period of nation-centrism in the 1930s.20 The accepted account is that New Zealand literary cultural nationalism can be historicized around The Phoenix, a small four-issue Auckland University College student journal published 1932–33, whose contributors, James Bertram, R. A. K. Mason, Allen Curnow, Charles Brasch, J. C. Beaglehole, and A. R. D. Fairburn, together with Frank Sargeson, went on to dominate New Zealand literature until the 1970s (Reference SchraderSchrader). The first journal dedicated to the “criticism and scholarship” of Aotearoa New Zealand literature, Journal of New Zealand Literature (JNZL), was published in 1983. In his editorial for the first issue, Frank McKay justifies the publication on the basis of an increasing awareness of the national literature. He notes that all six (at that time) universities teach the national literature “as a distinct and significant area of study” (Reference McKayMacKay 1). The journal includes two parts: the first provides summaries of new poetry, fiction, criticism and drama, and the second comprises five critical essays. Sebastian Black’s summary of new drama for 1983 is significant in relation to the current discussion in that he notes that many New Zealanders in 1983 were outraged at the very idea of a national theater (as opposed to performances of British and North American plays) (Black). However, he also records that there were also those “who struggled to create a theatrical environment in which indigenous work might flourish” (Reference BlackBlack 1). The five critical essays are notable in that three engage with work by Pasifika and Māori writers (Alistair Campbell and Witi Ihimarea and waiata aroha [Māori love poems]).

It is this stage of nation-centrism that most clearly announces the connection between Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand as “second-world” societies, as each exhibits their ambiguous status of being “both imperialised and colonising” (Reference LawsonLawson). For the desire to speak of local experience and to record the difference from Britain was championed as an anticolonial development. However, very few First Nations writers were included in the constitution of this difference. What appears clear from 2023 is that the ongoing need for settler cultures to attest maturity and attainment was enacted along the White mythologies of colonialism.

Māori/Pākehā writer and academic Tina Makereti illustrates the effects of this thinking. Her first diagram (Table 4.1) sets out how Māori literature is positioned in syllabi according to colonial periodizations and nation-centrism. She proceeds by offering two alternatives, in which she sets out a “Whakapapa [genealogy] of Māori Literature.” Her final diagram (Figure 4.1) recognizes the linearity of generation but also captures interrelationality, for – as she writes – “culture is always in flux, and colonisation – and the ongoing process of colonisation – shapes, limits, distorts and shifts how we know and tell our own stories. We are constantly spiralling back to reconnect and re-enact that whakapapa.”

Table 4.1 Māori literature in a conventional syllabus of Aotearoa New Zealand literature

Figure 4.1 Whakapapa [genealogy] of Māori literature

Makereti’s reconfiguration highlights the profound differences between Western and Māori conceptions of time and history, especially the telos of modernity and “universal history” by which Māori people only come into (literary) being in the 1970s and then only according to the criteria of conventional canonicity.

Makereti’s alternative whakapapa offers tangible ways of decolonizing the problem of linearity, history, and literature. A colleague and I who teach an Honours Year module on writing the world will alter the offering according to her model. We have taught the course as a dialogue between John Donne’s poetics of discovery relative to European colonialism and Shirley Hazzard’s 1980 novel of the post-War globe, Transit of Venus, whose title links the narrative to Cook’s discovery of Australia. The course thereby connects a seventeenth-century English poet with a twentieth-century Australian expatriate novelist. However, heeding Leane’s call to reinstate the erased First Nations peoples and Makereti’s disruption of literary genealogy, it is clear that we need to include Alexis Wright’s Carpentaria, discussed above in this module. Understood according the Makereti’s literary model, Wright’s Carpentaria both predates and postdates Donne and Hazzard.

The third stage in the development of English literary studies in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand dates from the 1980s in both countries and reflects the importance of postcolonial studies and then, more problematically, of “World Literature” and multicultural literatures to literary studies. Deploying Dixon’s useful schematization of literary scale, which he bases on the location of each text and the various spaces of its readerships, we can see the ways postcolonialism expanded or multiplied the relationships of these two national literatures, though not necessarily in the same ways and certainly not in relation to each other. Perhaps because of the issues of scale, there has been a consistent tendency of each to read and compare their national literatures alongside other postcolonial contexts from much further afield, especially Canada, the Caribbean, South Asia, and Anglophone Africa. For Aotearoa New Zealand, there is also the additional sense of their interconnections with Pasifika countries. The focus and scales proposed by “World Literature” claim very little interest in the Global South and certainly not in Oceania.

The category of “postcolonial” can be fraught in “second-world” societies such as Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand for First Nations peoples because of its perceived potential to erase the ongoing practices of the “second” or ongoing settler colonization and to merge the First Nations with settler subjects as fellow “colonials.” The concept and practices of decolonization, the fourth and current stage, have the potential to clarify the perceived problematics of the “postcolonial” in three main ways. The first is the identification of colonizing practices as ongoing and active rather than as historical occurrences. Secondly, the active element signaled by the prefix de in decolonization, stresses the active intervention into and against an identified reality. In Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand, this means that the researcher or teacher must declare their own standpoint and its implications. The third shift relates to the reach of the term, which extends from the structures that underpin social and cultural institutions to everyday activities and interactions (Reference Elkington, Jackson and KiddleElkington, Jackson, Kiddle, et al.). Most literary studies students in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand understand the decolonization of literary courses as part of this larger sociopolitical movement, which is tangibly supported by their institution of study – which is not to deny ongoing inequities. Nor is it a metaphorization of decolonization, though its potential diffuseness needs to be addressed and discussed with students so that its specific histories and contexts are not lost (Reference Tuck and YangTuck and Yang).

In disciplinary terms, too, the initiative of decolonization functions as a more comprehensive imperative. While some institutions in both Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand included multiple courses framed by postcolonial perspectives in the 1990s and early 2000s, most faculties usually only had one or two courses dedicated to literature in English outside the canon of English and (White) North American writing: one on the national literature and one on Anglophone postcolonial literature. In the majority of institutions, the postcolonial intervention, along with the literature of settler “national” intervention, which promoted courses on the literature of Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand, was introduced into the curriculum without significant disruption to the canon. Courses on Shakespearean drama, Romanticism, or Modernism remained largely unchanged. Decolonization, however, comprehends the entire curriculum. In Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand, the decolonizing process is understood as necessary for all courses and all pedagogies.

Pedagogical Strategy 3: Rethinking Written and Spoken Languages

One of the most basic issues for decolonizing literary studies in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand is the relationship between written and spoken language. As Rosemary Salomone observes in The Rise of English, colonization was driven by the ethos of “one nation, one language,” or one empire, one language (Reference Salomone15). The great number of Indigenous languages in Australia, spoken by small groups of people, stands in contrast to the shared language of te reo Māori, though R. M. W. Dixon’s research identifies common features across many of Australia’s original languages (Reference DixonAustralian Languages). In both countries, however, language, culture, and country are equally inseparable.

All 250 of the languages of First Nations Australians and the various versions of te reo Māori were oral rather than written languages. The original transcription of languages into Latin script was undertaken by early colonials and missionaries in these countries and many others across Oceania. A solely oral language is not an inherent cultural deficit. Rather, language did/does operate within the interrelationship and immanence of country and culture, past and present. The Meriam linguist Bua Benjamin Mabo, from Australia’s Torres Strait Islands, writes: “Keriba gesep agiakar dikwarda keriba mir. Ableglam keriba Mir pako Tonar nole atakemurkak” (The land actually gave birth to our language. Language and culture are inseparable). So, too, recent studies reinforce the particular relationship between land, language, and well-being for Māori people (Reference Matika, Manuela, Houkamau and SibleyMatika, Manuela, Houkamau, and Sibley). Dispossession, forced removal, and colonization have had profound and particular consequences for the interconnections of language and culture. Decolonizing approaches to the fundamental issue of language include the contextualization of written and oral literatures and their respective capacities and intensities through the inclusion of spoken, sung, and performed texts alongside written texts. Tina Makereti’s critique of conventional literary periodizations (above, Reference Makeretip. 000) highlights the misconceptions that arise from a solely scriptal criterion, which presents First Nations peoples of Australia, Aotearoa New Zealand, and the Pacific as having no poetry, drama, or storytelling prior to colonization and their induction into Western modes of representation. As this is clearly untrue, the criteria must be rethought and expanded to include inter alia the particular forms of immanence that connect country and culture and cultural expression. This perspective also casts light on the separation and disembodiment that occurs with scriptal records and representations and enables comparison of ontologies of memorial continuance and the archival memory-shelf of the written text.

This defetishization of the written text needs to be kept in balance with the achievements of First Nations writing in more recent times, so that questions of the flow between ancient and modern modes are considered while the leap into the scriptal mode and, most often, into the language and forms of the colonizers, is also recognized and traced. These discussions are usefully mapped according to the range of continuities and discontinuities of history and of the individual writer and consider the range of work up to contemporary experimentalism and narratives focused on contemporary urban life.

There is also an expanding body of collaborative work that involves translations from First Nations languages into English and vice versa. The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) provides a detailed list of many of these texts, as does the National Library of New Zealand.21 It is also possible to access recordings of singing with text in both the original language and English, with some also including performances. The official recordings of the glorious Yolngu musician Gurrumul are available on the Internet.22 Also, the contemporary singer, Gamilaraay and Birri Gubba man Mitch Tambo, has recorded one of Australia’s unofficial national anthems, “You’re the Voice,” in Gamilaraay language and including the wide diversity of Australia’s people.23 Ngā Hinepūkōrero, the Spoken Word Collective, moves between English and te reo Maori.24

Students respond very well to song and performance poetry, and it is a form that sets up traditions and connections outside the English literary canon. They also have access to the work via the popularity of slam poetry more generally. Throughout Aotearoa New Zealand and the Pacific, and increasingly in Australia, performance poetry has become a powerful form where traditional performance meets contemporary poetics of critique (Reference Stavanger and Te WhiuStavanger and Te Whiu). The spoken word poetry of Selina Tusitala Marsh, the first Poet Laureate of New Zealand (2017–19), is a great exemplar of these interconnections. Her performance of her poem “Unity” at Westminster Abbey for Commonwealth Day in 2016 harnesses this raft of traditions and techniques to deliver a stinging critique of Pacific colonization.25 This newly animated genre is also thriving in Australia amongst First Nations poets including Djapu social activist and writer from Yirrkala in East Arnhem Land Melanie Mununggurr-Williams, who won the 2018 Australian Poetry Slam National Final with a poem “I Run” that articulates the dilemma of being caught “between a Western white man’s world and ancient Aboriginal antiquity.”26 So, too, the renowned comedian Steven Oliver, of Kuku-Yalanji, Waanyi, Gangalidda, Woppaburra, Bundjalung, and Biripi heritage, has produced performances pieces that invite conversation across communities and also claim a First Nations queer identity.27

Pedagogical Strategy 4: Formalist Analysis and the Question of Value

Ironically, enough, the raft of rhetorical tools within conventional literaryanalysis has a powerful role to play in the decolonizing of critical practices in the classroom when they are harnessed as one mode amongst others for reading First Nations texts. Close readings and formal literary analysis open up many First Nations texts, though its modes may be unfamiliar to some students. Relative to the performance poetry discussed above, for example, a formalist analysis could provide one vocabulary for mapping the networks between speaker, text, and reader/audience that are created by the dynamics of these texts. How does the call to the addressee articulated in a spoken word poem relate to that of, say, oratorical and lyrical apostrophe and their emphasis of the “circulation or situation of communication itself” (Reference CullerCuller 59). To what extent does the Western rhetorical tradition enable ways of engaging with these new Spoken Word texts, and what are the limits of this mode of analysis?

The deployment of rhetorical analysis can be productive also in that it enacts formality, in its other sense of that word, as in ceremony and protocol. It is an act of respect across cultures and traditions and, by the terms of that tradition, accords the work aesthetic value in the conventional terms the discipline (see below, for a discussion of value). In the Western tradition also, the study of rhetoric predates English, as its origins are ancient Greece and Rome, thereby complicating temporality and tradition in productive ways. Of course, the mirror process is also necessary. How might our study of a contemporary spoken word poem about being-in-place alter how we read voice, persuasion, and nature in a canonical text such as Shelley’s “Ode to the West Wind”? How might a spoken word poem of expressive intensity shift our reading of the lyric, or of the dramatic monologue?

Teaching Spoken Word poetry often leads students to question the political potential of poetry or of literature and art more generally. How can a poetic act, shared between a limited group of people, bring about social change, which is an integral aim to much of this work? Can words affect “the decision of the judge,” as is the aim of oratorical apostrophe? Did Selina Tusitala Marsh’s performance change the British Commonwealth’s attitudes or policies regarding the South Pacific? These questions are necessary and productive as a decolonizing method. They focus on the diversity of investments from the creators, public performances, audiences, and feedback, building community and resilience and connecting our work in the classroom to these various contexts. These questions of investment, motivation, and effects relate in part to those of literary value. The teaching of Australian and Aotearoa New Zealand literary studies and postcolonial literatures that were based on a canon-forming “nation-centrism” model necessitated frameworks that opened up multiple value systems, which were often new to students and sometimes met with resistance. Students educated via New Critical universalism and an aesthetics of literary afflatus, are ill prepared to approach reading practices that trace cultures coming to writing. Much of the literature of “second-world” societies is not aurified. Students have not heard of the writers or the texts, so they are, at best, considered to be unproven and open for judgment as well as criticism.

In discussions of literary value, it is useful to work with students on mapping the range of values at work across the fields of literary and visual cultures prior to focusing on First Nations texts specifically. The first question might ask what texts warrant inclusion in any literary study. Students can list the range of their own reading and viewing and their different expectations from popular fiction and genre fiction, television series and films, and university syllabi. The list might also include family discourses, text chains, and graffiti. In diverse classrooms such as those of Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand, these lists will include texts from non-English sources. They will also be accessed and experienced in various forms. How do students assess the value of this amalgam? What is the experience of moving across the range of styles and the genres and levels of complexity? How does engagement with one form or mode affect the experience of another? To what extent do they consume and/or create these texts. How does this map read them?

Disagreement is welcome in this discussion as a way for students to experience shared and divergent values according to relative functions and purpose. Students coming to the diversity of First Nations literatures need to respect this range and learn how to articulate its particular location in the literary field. A final note on the question of value, which can be raised in light of the recognition that all literature has demographics and target audiences, is that they may not be the primary readership for the text they are reading or hearing or viewing. First Nations writing in English presumes a settler audience to some extent, but there is, from the outset, a displacement of the primacy of the Western reader. First Nations students will have a very different – and primary – position.

Pedagogical Strategy 5: Research and Citations for Essays

Students often find the limited number of resources about many First Nations writers – or any writers from Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand, for that matter – very challenging, as there is often little critical material. There are key reference books that are readily available, including literary histories and “companions” (Reference Heiss and MinterHeiss and Minter; Reference WilliamsWilliams; see also BlackWords (Teaching) in the AustLit database), and First Nations scholars such as Martin Nakata28 and Linda Tuhiwai Smith (Decolonizing Methodologies). These need to be historicized, but those from the last decade are generally very useful. Jeanine Leane’s pointer toward historical discourses (discussed above,) provides one methodology by which students can contextualize their essays and arguments. The reach of trans-Indigenous approaches may be helpful in this context too, as they assist in breaking down the binary that still privileges settler-culture writing. Chadwick Allen’s foundational text Trans-Indigenous: Methodologies for Global Native Literary Studies is very useful here, and it has been strongly endorsed by Māori scholar Alice Te Punga Somerville. Allen’s more recent essay, “Indigenous Juxtapositions: Teaching Maori and Aboriginal Texts in Global Contexts,” is also very insightful, especially for teachers beyond Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand.

The particular challenges of researching in this field need to be discussed with the students as a particular aspect of decolonized study. Whatever decisions students adopt regarding their approach, it is imperative that they engage with secondary material from First Nations readers and writers. Finally, there may be First Nations students who are confident to follow pathways that may be unfamiliar to the teacher or to other students but will create meaningful and transformative knowledge and methods to literary studies.

Conclusion: Present and Future Challenges

One of the many challenges of decolonizing literary pedagogies in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand is the maintenance of substantive practices in environments where “decolonization” is often adopted as a veneer of rightful thinking within the endless double-speak which plagues our universities. Right thinking, including decolonization, has been compromised in Australia – and to a lesser extent in Aotearoa New Zealand – by its deployment as empty rhetoric, an item on the checklist for global university rankings. In Australia specifically, this performance of virtue has operated as a blind to obscure the systematic dismantling of Australian working conditions in the academy, the induction of universities into the global labor market, and a reversion to colonial-era class systems.

A second challenge, in the context of the Anthropocene, is the turn to Indigeneity as a solution to the disasters of the environmental destruction and late-modern disenchantment. Non-Indigenous readers and scholars – and I include myself in this reminder – need to approach First Nations literatures, and model for our students, the value of this work on its own terms. To do this, we need to be guided by First Nations writers, academics, and students. Decolonization requires the decentering of authority and accepting the invitation to participate on the limited, partial terms that are yet available. Hopefully, literary studies provides some guidance for this process.