Recent developments and the baseline forecast

Our revised baseline forecast

The gradual strengthening of the global expansion that we projected in the February 2017 Review, following the seven-year low for world GDP growth reached in 2016, seems to be materialising. Recent data have remained mixed, but suggest on balance that global growth is strengthening moderately and becoming more broadly based, including among the members of the Euro Area and among emerging market economies that have suffered severe recessions in recent years. We now expect global output growth to pick up to 3.3 per cent this year from 3.1 per cent in 2016 and to strengthen further, to 3.6 per cent, in 2018. Our projection for growth in 2017 has been revised up by 0.2 percentage point since February while our forecast for 2018 has been revised up by 0.1 percentage point. The upward revisions for both years are widely spread among the major economies and small in most cases.

As discussed below, our new forecast has been constructed at a time of unusual uncertainty, about economic policies in the United States; about prospective policies in the four largest economies of the European Union, all of which have elections in the coming months; about geopolitical developments in the context of recent tensions; and also about the interpretation of recent data showing large increases in business and consumer confidence in the US and several other advanced economies, generally unmatched, as yet, by ‘hard’ data on spending and activity. There are therefore significant risks to our forecast on both the upside and the downside, but the downside risks that could derail the gathering momentum of global growth are of particular concern.

Recent economic developments

In the advanced economies, moderate growth has continued, with activity now probably close to full employment levels in the US, Japan and Germany, although subdued wage inflation, even in these countries, continues to raise questions about employment gaps. In the Euro Area, the dispersion of growth rates has generally narrowed, and unemployment, though still differing widely among member countries, has recently fallen to 9.5 per cent on average, which is below the halfway point between its March 2008 trough and its March 2013 peak. Data on activity in early 2017 have been mixed, with ‘soft’ survey data – PMIs and indicators of consumer and producer confidence – notably positive, reaching six-year or longer-term highs in some cases, in Europe as well as the US – while ‘hard’ data have shown fewer signs of strengthening growth.

Among the major emerging market economies, Brazil remained in deep recession in late 2016 and clear evidence of an upturn has yet to appear, but recovery is expected to begin in the course of this year. Russia seems to have begun to recover from its recession. India's GDP growth has remained the fastest among the major economies and does not appear to have suffered significantly from last November's demonetisation of more than 80 per cent, in terms of value, of the currency notes in circulation. China's growth in the year to the first quarter of 2017 picked up to 6.9 per cent; the new official target for 2017 as a whole, of ‘around 6.5 per cent’, thus allows some deceleration in the remainder of the year.

Consumer price inflation in the advanced economies has risen significantly in recent months, largely because of rising energy prices, and in the US it has recently been close to the Federal Reserve's medium-term objective. Core inflation rates have been more stable, remaining well below targets in the Euro Area and Japan. Annual wage increases have picked up somewhat in the US, while remaining below 3 per cent. There has been no significant rise in wage inflation elsewhere. Among the major emerging market economies, inflation has fallen close to targets in Brazil, India and Russia. In China, there has recently been a sharp divergence between consumer price inflation, which has fallen away from the 3 per cent target, and producer price inflation, which has risen sharply.

Economic policies of the new US administration

Recent international financial market developments have been strongly influenced by the evolution of the economic policies of the new Trump administration.

Since his inauguration on 20 January, President Trump has implemented, through executive actions, measures to reduce regulations in some areas, including environmental pollution, but also to increase restrictions on immigration, although the immigration restrictions have been suspended as a result of legal action. He has also called for reviews of post-crisis reforms of financial sector regulation, including the implementation of the Dodd-Frank Act, particularly its ‘orderly liquidation authority’ intended to help regulators resolve failing institutions.

With regard to fiscal policy, uncertainty predominates. On 16 March, the president delivered to Congress his ‘budget blueprint’ proposals for discretionary spending, including significant expansions in expenditures on defence and homeland security, offset by broad and significant cuts in other discretionary programmes. Support for these proposals in Congress is unclear.

The administration's fiscal plans were complicated by the withdrawal from Congress on 24 March of a bill, supported by the President, to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act (‘Obamacare’), which would have involved significant tax cuts. On 26 April, the Treasury Secretary and the Director of the National Economic Council outlined proposals for significant reductions of corporate and personal income taxes and to repeal the estate tax. The proposals did not include a ‘border adjustment’ to corporate income tax, which has been proposed in Congress as a way to finance other tax cuts (see February 2017 Review, F17). One independent estimate of the cost of these proposals is between $3 trillion and $7 trillion over ten years, with a base-case estimate of $5.5 trillion.Footnote 1 This is equivalent to 1.6–3.7 per cent of 2017 GDP a year, with a base-case estimate of 2.9 per cent of 2017 GDP a year. However, Treasury Secretary Mnuchin asserted, in announcing the proposals, that “This will pay for itself with growth and with reduction of different deductions and closing loopholes”. Support in Congress for these tax proposals, like the expenditure proposals, is unclear.

Detailed budget proposals for the 2018 fiscal year, starting this October, are due to be released by the end of May, possibly including proposals for more widespread tax reform and increased infrastructure spending. The Treasury Secretary, having indicated earlier that he expected tax reforms to be approved by Congress by the end of August, stated on 20 April that his deadline had been pushed back to the end of 2017.

With regard to the federal budget in the current fiscal year, a bipartisan agreement was reached in Congress at the end of April to provide funding for government operations through the end of the fiscal year in September, thus avoiding a partial government shutdown. The statutory debt ceiling suspended by the 2015 Budget Act came back into force on 15 March, at which point the Treasury Department suspended the issuance of debt and turned to extraordinary measures to maintain funding of government activities. Such measures are expected to be exhausted in the third quarter of the calendar year, so that the debt ceiling will need to be raised by then by Congress.

In the area of international trade and exchange rate policy, where early dramatic action seemed promised by President Trump – including declaring China a currency manipulator and imposing significant tariffs on Chinese and Mexican imports – policies have thus far been more cautious. There has, however, been continuing rhetoric in favour of protectionist, mercantilist policies focused on bilateral trade imbalances, broadly in line with President Trump's apparent advocacy of protectionist trade policies in his inaugural address on January 20, when he said: “We must protect our borders from the ravages of other countries making our products, stealing our companies and destroying our jobs. Protection will lead to great prosperity and strength”. The main actions and announcements in this area since the president's inauguration are summarised in Box A.

Monetary policy

The Federal Reserve raised its target range for the federal funds rate by 25 basis points, to 0.75–1.00 per cent, on 15 March, but left unchanged its median projections of last December for the rate at the end of this year and the end of 2018. Its projections of GDP growth, unemployment, and inflation were also left broadly unchanged. This implies two further increases of 25 basis points this year, and three more next year. The minutes of the Fed's March meeting indicate that it expects to begin reducing the size of its balance sheet later this year, following the major expansion associated with its large-scale asset purchases of 2008–14.

The European Central Bank (ECB), at its March meeting, left its interest rates and asset purchase programme unchanged but amended its forward guidance to signify that the risk of deflation had disappeared, along with the associated sense of urgency. The Bank of Japan has left its policy parameters unchanged since last September.

Among the emerging market economies, official rates in Brazil were lowered in two further steps, of 75 and 100 basis points, respectively, in late February and mid-April, to 11.25 per cent. Russia's central bank lowered rates by another 25 basis points step in late March and by a further 50 basis points in late April, to 9.25 per cent. Meanwhile, China's central bank has recently guided market rates slightly higher without any change in benchmark rates. In Mexico, the central bank raised its benchmark rate by 25 basis points, to 6.5 per cent, at the end of March; this followed five increases of 50 basis points each since early 2016 intended to restrain above-target inflation and counter downward pressure on the peso.

Financial and foreign exchange markets

The rise in government bond yields in the advanced economies from the lows reached last July, which was discussed in the February Review, tapered off at the end of 2016, and between late January and late April ten-year yields fell back by about 25 basis points in Canada and 15 basis points in the US and Germany, while they remained broadly unchanged in Japan and France, and rose by 20 basis points in Italy and Spain. In the US, the decline occurred entirely from mid-March, and by late April, rates had fallen back to the levels prevailing in late November 2106, in the weeks following the US elections.

Recent movements in bond yields seem to have been influenced by a number of factors, including increased doubts about prospects for fiscal expansion in the US, particularly following the failure in mid-March of the Republican effort to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act; the disappointment of expectations that the Fed would steepen its path of expected future rate increases at its mid-March meeting; the Bank of Japan's operations to stabilise long-term interest rates; and, in the Euro Area, concerns about political prospects in France and Italy ahead of elections, and associated safe-haven demand for German assets. The spread between US and German bond yields has recently, at more than 2 per cent, been the widest since the late 1980s, before German unification. Within the Euro Area, spreads relative to German bond yields have widened in recent months in both France (to about 0.7 per cent before the first round of the presidential elections on 23 April, after which they narrowed to about 0.5 per cent) and Italy (to about 2 per cent). Recent movements in European government bond yields in relation to political risk are discussed in Box D.

Among the major emerging market economies, bond yields have fallen further since late January in Brazil and Russia, reflecting downward trends in inflation and official interest rates, while they have risen somewhat in China as the central bank has tightened monetary conditions.

Exchange rate movements in the period since late January have been mixed, with the US dollar broadly strengthening up to mid-March and subsequently falling back. The trade-weighted value of the US dollar in late April was little changed from late January and about 4 per cent below the 14-year peak reached at the end of last year. Recent currency movements seem to have been related to a number of factors, including changes in interest and inflation differentials. In late April, the value of the US dollar was about 5 per cent higher than in late January in terms of the Canadian dollar, but 2–3 per cent lower against the yen and sterling, and 1 per cent lower against the euro. The particular weakness of the Canadian dollar in recent months seems to have been due partly to revised expectations about domestic monetary policy following surprisingly low domestic inflation data, weaker global oil prices, and concerns about US–Canada trade relations. In terms of emerging market currencies, the US dollar is broadly unchanged relative to late January against the renminbi and the Brazilian real, but 4–6 per cent lower against the rouble and the Indian rupee. President Trump's statement on 12 April that the dollar was “getting too strong” seemed to have little effect on the markets. The Mexican peso, having depreciated against the US dollar by 16 per cent between the election and inauguration of President Trump, has since recovered almost all of this decline as expectations of US actions against Mexican imports have waned and Mexican monetary policy has been tightened.

Box A. Recent initiatives of the US government relating to international trade

January 23: President Trump announced the withdrawal by the US as a signatory to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and from TPP negotiations, and directed the US Trade Representative to begin pursuing, wherever possible, bilateral trade negotiations to promote American industry, protect American workers, and raise American wages.

March 1: President Trump delivered to Congress a preliminary Trade Policy Agenda that promised a focus on bilateral, rather than multilateral, trade negotiations and a more limited role for the WTO.Footnote 1 At about the same time, the Director of the President's new National Trade Council argued that US trade policy should focus on reducing the US trade deficit (as a means of boosting US economic growth) through new bilateral trade deals more favourable to US net exports.Footnote 2

March 18: At the instigation of the US, the March Communique of the G-20 finance ministers' meeting of 17–18 March dropped wording that had been standard in the group's earlier statements, that the member countries vowed “to resist all forms of protectionism” and replaced it with the statement that members were “working to strengthen the contribution of trade to our economies”. (A similar substitution of wording was made in the IMFC Communique of 22 April.) The G-20 Communique reaffirmed ministers' commitments to other forms of international economic cooperation, including to “further strengthening the international financial architecture and the global financial safety net with a strong, quota-based and adequately resourced IMF at its centre”.

Late March: a draft of a formal notification by the administration to Congress regarding the intention to renegotiate NAFTA (which Trump had referred to as “the single worst trade deal” ever approved by the US) was reported to have proposed only relatively minor changes to the agreement, the most significant being revisions to rules on federal procurement from US firms and rules of origin.

March 31: the President directed the Department of Commerce and US Trade Representative to provide within 90 days an ‘Omnibus Report on Significant Trade Deficits’, which will examine the US's significant bilateral trade deficits in goods and consider whether they are caused by such factors as non-tariff trade barriers, dumping, cheating, state subsidies, free trade agreements, weak enforcement of trade agreements, currency misalignments and manipulation, WTO rules and interpretations, differing tax systems, and lack of reciprocity.

April 7–8: Meetings between President Trump and President Xi of China on 7–8 April led to agreement on a ‘100-day plan’ to address their bilateral trade imbalance, with details to be announced.

April 14: The US Treasury, in its twice yearly Report on the Foreign Exchange Policies of Major Trading Partners found that no major trading partner, including China, met in the second half of 2016 the criteria established in legislation for currency manipulation. However, the Report introduced a Monitoring List of countries that met two of the three criteria, comprising China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Germany and Switzerland.

April 18: The President signed an Executive Order aimed at strengthening and enforcing his ‘Buy American, Hire American’ agenda.

April 20: The Secretary of Commerce initiated an investigation into whether steel imports threaten national security. The report, to be delivered within 270 days, will determine whether steel imports cause US workers to lose jobs needed to meet the security requirements of the domestic steel industry, as well as any harmful effects of steel imports on government revenue and US economic welfare. If the report concludes that steel imports threaten to impair national security, the President will take action to eliminate the negative effects.

April 24: the Secretary of Commerce announced that the US would place countervailing duties of 3–24 per cent on five Canadian lumber exporters after concluding that Canada subsidises its industry in a way that hurts the US. The Canadian government said that Canada would vigorously defend the interest of its industry, including through litigation.

April 26: President Trump agreed with the prime minister of Canada and the president of Mexico not to terminate NAFTA at this time and to proceed to renegotiation of the agreement.

April 27: the Secretary of Commerce (Secretary) initiated an investigation to determine the effects on national security of aluminum imports, similar to that relating to steel imports (see April 20, above).

Notes

1 2017 Trade Policy Agenda and 2016 Annual Report of the President of the United States on the Trade Agreements Program: https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/files/reports/2017/AnnualReport/AnnualReport2017.pdf.

2 Peter Navarro, ‘Why the White House Worries About Trade Deficits’, Wall St Journal, 7 February, 2017: https://www.wsj.com/articles/why-the-white-house-worries-about-trade-deficits-1488751930.

Equity markets have been generally buoyant since late January, rising by 4–6 per cent in the US, Germany, and Italy, and by 8 per cent in France, mainly following the first round of the presidential elections. Stock market prices are little changed since late-January in Japan, China, and Brazil. Major indices in the US reached historic highs at the beginning of March, subsequently fluctuating around slightly lower levels.

Commodity markets

After three months of fluctuation in a narrow range, global oil prices fell by about 10 per cent in early March, from about $54 to about $48 a barrel, following the release of data showing a surprisingly large recent build-up of US crude inventories. Later indications that the production agreements reached last November among OPEC and other producing countries will be renewed when they expire in June were offset by new evidence of rising US production and inventories, so that in late April prices were broadly unchanged from early March and 7 per cent lower than late January.

The rise in other commodity prices discussed in the February Review came to a halt in mid-February. Since then, the Economist all-items index, in US dollar terms, has fallen by about 7 per cent to a level still 3 per cent higher than a year earlier.

Risks to the forecast and implications for policy

A striking feature of the current conjuncture is the unusually high level of uncertainty on three fronts:

• Data uncertainty: in recent months, as described in the country sections below, ‘soft’ data obtained from surveys of purchasing managers, businesses and consumers have become markedly more positive, especially in the US but also in several other economies, but ‘hard’ data obtained from actual spending and production have generally been more subdued. This divergence has contributed to wide differences among some short-term growth forecasts. For example, the Atlanta Fed's ‘GDP Now’ forecast of US GDP growth in the first quarter of 2017, just before the release of the first official estimate, was 0.2 per cent at an annual rate, while the New York Fed's comparable ‘now cast’ was 2.7 per cent; the outcome (meaning the first official ‘advance’ estimate) was 0.7 per cent. Our forecast makes little use of ‘soft’ survey data, but the apparent recent improvement in sentiment may translate into hard data in the near future: after all, ‘animal spirits’ matter. This may be an upside risk to our growth forecast. On the other hand, if the expectations of consumers and businesses are disappointed, there may be reactions in asset markets to the extent that these expectations are reflected there.

• Policy uncertainty in the US: as outlined above, there is currently an unusually high degree of uncertainty about policies with regard to the budget, as well as international trade, in the world's largest advanced economy. Our forecast assumes no change in established policies on either front, so that the possibility of well-designed fiscal reforms, for example, poses an upside risk to our growth forecast, even for the longer term, while an unproductive widening of the fiscal deficit resulting, say, from regressive tax cuts, could just bring higher interest rates or inflation, or both, which could damage growth – a downside risk. With regard to prospects for US inflation, additional policy uncertainty arises from the unusual turnover of senior officials that is in prospect at the Federal Reserve Board: three out of the seven governor positions are currently vacant and awaiting presidential appointments, and the terms of the Chair and Vice Chairman expire in February and June 2018, respectively. This gives President Trump an unusual opportunity to reshape the Fed in a relatively short period of time if he is so inclined, subject to the consent of the Senate. With regard to international trade, the actions of the administration so far have been relatively cautious, but protectionist policies have been promised, and the possibility of their implementation is a clear downside risk to our US and global growth projections.

• Political uncertainty. In Europe, elections in all of the Euro Area's three largest economies – and also the UK – within the next ten months pose upside and downside risks for our forecast and for the future of the Euro Area and the EU. There have also, in recent weeks, been heightened geo-political tensions, particularly in the contexts of Syria and North Korea, which appear to have contributed to increased risk aversion at times in financial markets.

The risks to our forecast are not all related to these uncertainties. An example is the risks relating to the build-up of credit in China, discussed in earlier issues of this Review and in the section on China below. But in the context of the above uncertainties, the following risks stand out:

First, the recent divergence between ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ data for several advanced economies may be resolved either by an acceleration of economic growth or by a disappointment of expectations. In the latter case, there is a risk of a reversal of recent gains in asset markets, especially equity markets. These gains may have been based partly on over-optimistic expectations of the benefits to economic growth and corporate profits of the policy agenda of the new US administration, or of the likelihood of its implementation. Such expectations seem to have begun to recede in recent weeks in the face of political developments, and equity markets have retreated a little from their peaks. These falls could go further. A number of indicators suggest that equity markets in the US and other countries are richly valued. Thus Shiller's cyclically adjusted price–earnings ratio (CAPE) for the US S&P 500 stock market index has recently been close to 30 (see figure 2).Footnote 2 It has been higher only in 1929, when it reached 33, and in the years around 2000, when it reached 44. In both cases, sharp market declines followed these high readings. Sharp equity market declines would be likely to damage both private consumption and investment.

Figure 1. Contributions to world GDP growth (from four quarters earlier)

Figure 2. Shiller price to earnings ratio for the S&P 500

Second, the Fed may increase interest rates faster than we assume in our forecast, for example if US fiscal expansion increases prospective inflationary pressure in the economy, which is already operating close to full employment. Such additional increases in US interest rates would tend to crowd out not only private domestic spending, partly by reducing asset prices, but also net exports, partly through appreciation of the US dollar. The US external current account deficit would therefore tend to widen, contrary to the administration's objective that it should be reduced in order to boost US economic growth. This could lead to increased protectionist pressures, and the widening of global payments imbalances could also jeopardise international financial stability.

The rise in US interest rates and appreciation of the dollar would also have repercussions for emerging market economies, including increases in the debt burdens of countries with liabilities denominated in the US dollar. These are discussed in Box C. Foreign currency borrowing by emerging market governments, which played a prominent role in the emerging market crises of the late 1990s, has declined significantly in recent decades, and the external vulnerability of many of these economies has also been reduced by a shift towards flexible exchange rate arrangements and build-ups of international reserves. But foreign currency borrowing by the private sector has grown in many countries. Data from the Bank for International Settlements show that the foreign currency (predominantly US dollar) debt of non-bank residents in emerging market economies in Asia rose to about 38 per cent of GDP, on average, at the end of 2015 from about 31 per cent at the end of 2010, and that the corresponding ratio for Latin America increased to about 23 per cent from about 14 per cent in the same period.Footnote 3 Unless it is hedged – and there is little information on the extent of hedging – the associated exchange rate risk could carry damaging implications for the debt burdens of some emerging market economies, especially if the dollar appreciates further. Rising US interest rates will also put upward pressure on domestic interest rates in emerging market economies – especially economies with currencies tied to the dollar – with negative implications for economic growth and also, possibly, the development of domestic financial markets.

Financial pressures from expansionary US fiscal policy could be exacerbated if the administration's budget plans were to incorporate over-optimistic assumptions about US economic growth. One of the main objectives of the administration's fiscal (and other economic) policies is to raise the rate of US economic growth, including by reducing taxes, improving tax incentives, and increasing infrastructure investment. Officials have referred to objectives of 3 or even 4 per cent annual GDP growth. Thus Treasury Secretary Mnuchin, when outlining the administration's tax proposals on 26 April, said that, “We believe we can get back to 3 per cent or higher GDP (sic) that is sustainable in this country”.4 As discussed in the section below on the United States, it is difficult to see how such objectives could be reached in the short to medium term. If, nevertheless, such ambitious growth assumptions are used as a basis for official budget projections, the associated forecasts of the fiscal deficit are likely to be exceeded by out-turns, and this is likely to be anticipated by adverse developments in financial markets.

Third, given the unusually large turnover in prospect in membership of the US Federal Reserve Board in the coming months (see above), there is a risk that the Fed's independence may be diminished and that upward pressure on inflation may not be resisted by monetary policy. Grounds for concern on this score increased when President Trump stated in an interview in mid-April that he viewed the dollar as “getting too strong” and that he would prefer the Fed to keep interest rates low. If the Fed allowed inflation to rise significantly above its established objective, confidence in macroeconomic stability and longer-term growth prospects could be severely damaged.

Fourth, there are the risks arising from US-led protectionism. Protectionist or defensive trade policies damage economic efficiency and productivity growth by weakening competitive forces, raise domestic costs and prices, reduce real incomes, and risk a downward spiral of economic activity through successive international retaliatory measures. Thus far, the administration's actions in this area have been limited (see Box A), but preparatory work is in train on a number of questions, which may lead to counter-productive actions in the months ahead. Model-based estimates of the possible results of protectionist measure are provided in NiGEM Observations No.12.5 Risks from increased trade protectionism are also discussed in Box B.

Fifth, there are risks that the reviews of financial sector regulation being conducted by the administration could lead to more lax regulation and supervision of financial institutions, with adverse consequences for the danger of future financial crises.

Finally, the unusual concentration of national elections in the coming months in the four largest economies of the EU – France (the second round of the presidential election in early May, followed by parliamentary elections in June), the UK (June), Germany (September) and Italy (by February 2018) – poses substantial upside and downside risks for the future of the Euro Area and the EU. An upside risk to our forecast is that the election of governments favourably inclined towards the EU and to reforms needed to improve the working of the monetary union and the broader economy could re-energise the European project. Among the downside risks, the most extreme, which is not inconceivable, is that the elections of governments hostile to the EU and the monetary union could lead to the project's collapse.

Box B. Risks from increased trade protectionism

Economic downturns are often followed with loss of trust in the market economy. The inefficiencies of laissez-faire become more apparent and outshine its beneficial impacts. In such a process, free trade, which is perceived by the public to exacerbate the decline in real wages and increase the loss of jobs due to offshoring and international competition (Reference KruegerKrueger, 2004), is one of the main elements under threat. Accordingly, this box summarises the recent empirical evidence on the relationship between economic growth and openness to trade, particularly from the onset of the Great Depression, and finds that the classic positive relationship holds. In addition, we revisit the case that economists have made in favour of free trade and highlight the costs of trade protectionism.

Focusing on the evidence available before the financial crisis, the empirical literature has found that governments adopt trade-restricting policies whenever a country experiences a recession and/or a loss of competitiveness induced by an appreciation of the exchange rate (for a neat summary of the literature, see Reference Georgiadis and GräbGeorgiadis and Gräb, 2013). However, since the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis there has been scant evidence of an increase in tariffs, quotas and other standard protectionist measures (Reference RodrikRodrik, 2009; Reference Bown and BownBown, 2011). In a recent paper, Reference Georgiadis and GräbGeorgiadis and Gräb (2013) have offered an explanation that can reconcile the apparent break in the relationship between growth and trade protectionism that has taken place after the Great Recession. According to the authors, the apparent lack of trade restrictive policies is due to the fact that policymakers have recently begun to regulate trade in different ways. Governments no longer rely on standard trade policy to protect their domestic markets, as their room for manoeuvring has been reduced by World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules and other international agreements. Instead, they employ ‘murky’ trade measures, namely regulations that permit discrimination against foreign producers thanks to flaws and vagaries within trade deals. These fall mainly into the so-called ‘non-tariff barriers,’ which include conformity and technical compliance, domestic licensing, certificates of origin, health and safety regulations or buy-local clauses in stimulus and bail-out packages and so forth.

After an increasing use of ‘murky’ trade measures, recourse to more standard trade restrictive policy is becoming popular again. Recently, the European Union has revised its tariffs upwards for steel imported from China, with increases ranging from 18.1 per cent to 35.9 per cent for five years,Footnote 1 and there have also been warning signs of a trade war between the US and China.Footnote 2

It is baffling that policymakers have adopted such policies, neglecting the large strand of economic literature that has corroborated the beneficial effects of international trade on the economy. The topic has been subject to profound investigation and debate, yet the majority of economists recognise that greater openness has an overall beneficial impact on the rate of growth of the economy (Reference Winters, McCulloch and McKayWinters et al., 2004). A thorough survey by Reference SinghSingh (2010) further describes the channels of the gains from trade. Once a country opens up to trade with the rest of the world, it has the chance to funnel its resources into the production of those goods for which it has a comparative advantage. The benefits are twofold: on the one hand, the country has the possibility to import goods for which it has a comparative disadvantage at a cheaper price than the domestic one; on the other hand, the concentration of the production process on a narrower range of goods increases output. This means that, when a country begins international commerce, it experiences a boost in productivity, which in turn stimulates economic growth. The author also reviews other studies that explore further the way that trade impacts the economy. Barriers to trade are demonstrated to shield rent-seeking behaviours and strengthen monopolistic positions, reducing total factor productivity and the need to adopt state-of-the-art technology. This does not merely reduce the amount of output produced, but its quality as well, reducing the competitiveness in international markets. There is much noteworthy research highlighting the indirect, beneficial effects trade. These can be encapsulated into a view that trade ensures a more opportune environment for capital accumulation, therefore inducing profitable investments and a boost to the economy.Footnote 3

Reference KrugmanKrugman (1993) adds one further reason from a political-economy angle in favour of free trade to the list above. While it is certainly the case that one can find theoretical reasons that support the implementation of policies that restrict trade (some forms of departure from perfect competition), those usually presume a degree of sophistication from the part of the government that is likely to end up doing more harm than good. In addition, as the author points out, most research in this area finds that the benefits from such sophisticated policies are usually small.

Nevertheless, Reference SinghSingh (2010) admits that macro- and microeconomic empirical evidence clash. While the former resolves the nexus with a positive statement, the latter provides more mixed results. The significant, positive effects observed in the economy as a whole are harder to trace once they are analysed at the firm- or industry-level. Most advanced microeconomic literature departs from models based on the representative firm typical of the Heckscher-Ohlin model, and exploits firm heterogeneity. This literature inspects the so-called self-selection hypothesis, which maintains that only the most efficient firms have the tools to cope with higher sunk costs and fiercer competition faced in the international market. As a consequence, the best firms self-select into the export market. This undermines the narrative according to which trade boosts productivity, reversing the direction of the arrow of causality. All in all, trade is often considered to be an important tool in order to foster economic growth.

Despite these empirical results, policymakers seem willing to blow the dust off protectionist policies. As previously mentioned, the EU has raised its tariffs against steel imported from China. What this means can be easily seen with a simple economic exercise. Such measures are usually enforced on those goods whose imported price is lower than the domestic one, so that the majority of the cost falls onto consumers. Suppose imports are initially available at the free trade price of Pw, so that the quantity of imports is given by the difference between Qw and Sw. Should the government decide to raise an ad-valorem tariff for the imported good, the price faced by consumer would go up to Pp and the volume of imports would decline to the difference between Qp and Sp. As a result, consumer surplus would decrease compared to the case without tariff by the sum of the areas A + B + C + D. Producers, as a result of the increase in the price, would see their surplus increase by the area A. Area C, which represents the revenue raised by the tariff imposed on imports, would be appropriated by the government and areas B + D denote the deadweight loss. This simple economic exercise shows the detrimental effects stemming from the imposition of a tariff, a measure that policymakers should refrain from applying.

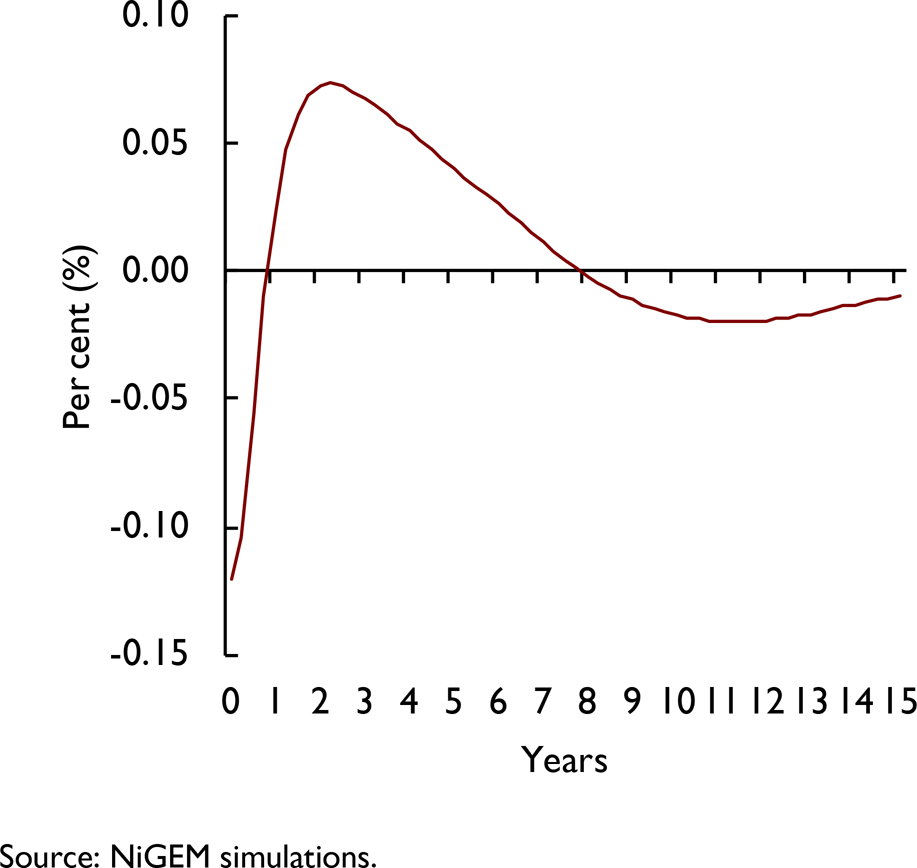

To gain a quantitative sense of the cost of imposing a tariff we run a scenario in the National Institute Global Econometric Model, NiGEM, where we look into the impact of the US introducing a 10 per cent tariff on all imports from China. As figure B2 shows, the tariff induces a temporary reduction of output which at its peak declines by 0.2 per cent relative to baseline values. As a result of the tariff, import volumes decline, which provides a boost to output. However, more than offsetting this channel, is the inflationary impact of the tariff via higher import prices that results in a squeeze of the purchasing power of consumers which ultimately leads to a fall in consumption, see figure B3. To conclude, the impact on the balance of trade in goods and services depends on the time horizon. On impact, the increase in import prices derived from the introduction of the tariff dominates the initial decline in imports and results in a worsening of the trade balance. However, as import volumes fully adjust to both the new prices and the decline in domestic demand the trade balance improves, see figure B4.

Figure B1.

Figure B2. US output (percentage difference from baseline)

Figure B3. US private consumption and consumer price inflation

Figure B4. US trade balance in goods and services to GDP ratio (percentage point difference from baseline)

Notes

1 Emre Peker (2017, April 6). EU Ramps Up Anti-Dumping Duties on Chinese Steel. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from: https://www.wsj.com/articles/eu-raises-anti-dumping-duties-on-chinese-steel-1491494207

2 Wang Wen (2017, March 27). A US-China trade war would cause huge damage and benefit nobody. Financial Times. Retrieved from: https://www.ft.com/content/3b49cd2a-1

3 See Reference SinghSingh (2010) for a review of research in this area.