Introduction

The language of the book of Qoheleth strikes any reader accustomed to classical Biblical Hebrew as odd and obscure. Characterized by a unique, often awkward, style and an unusual vocabulary, the Hebrew of this book is unparalleled in any known biblical or post-biblical text.

Scholars have attempted to account for these peculiarities in several ways. The most popular explanation refers to the date of the book’s Hebrew. According to broad scholarly consensus, Qoheleth’s language should be classified as Late Biblical Hebrew—a postexilic variety that differs from Classical Biblical Hebrew in many ways.Footnote 1 This explanation is, however, partial at best. Other books written in Late Biblical Hebrew, such as Esther or Chronicles, employ flowing, clearly formulated Hebrew, whose clarity sets it apart from Qoheleth’s language.

Other scholars suggest that Qoheleth is written in the so-called Israelian dialect, or, alternatively, that it reflects an otherwise underrepresented Hebrew vernacular.Footnote 2 Yet other theories assign the oddities of Qoheleth’s language to the influence of foreign languages, most prominently Aramaic. By the time the book was composed, sometime between the fifth and second centuries BCE, Aramaic was prevalent among Palestinian Jewry. This fact is clearly reflected in the lexicon, grammar, and syntax of Qoheleth.Footnote 3 Some scholars believe these Aramaic traits to indicate that the book was originally composed in Aramaic and then translated, not very skillfully, into a faulty Hebrew that repeatedly betrays its origin.Footnote 4 Another hypothesis, which has gained little acceptance, argues for Phoenician influence on the book’s language.Footnote 5

What all these theories have in common is their purely linguistic perspective—that is, they all assume that the problem of Qoheleth’s language should be solved via models and tools known from the discipline of linguistic studies. The present paper seeks to expand the boundaries of the study of Qoheleth’s language by introducing extralinguistic factors—especially cultural environment, intellectual-historical developments, and individual thought—into the discussion. Building on the work of prominent scholars who have analyzed Qoheleth’s extraordinary lexicon, I would like to suggest that Qoheleth’s author creates a personal idiolect, discuss the mechanisms governing this process, and present the historical and intellectual circumstances that gave rise to the unique linguistic project known as Qoheleth’s language.Footnote 6

Qoheleth’s Personal Lexicon: History of Scholarship

Almost all students and commentators of Qoheleth have attempted to analyze the book’s special lexicon. Two prominent contributions in this regard are Michael Fox’s influential analysis of key terms in Qoheleth and Antoon Schoors’ exhaustive and detailed treatment of the book’s vocabulary.Footnote 7 These and similar studies reveal an intriguing phenomenon, whose deeper significance has thus far not been acknowledged: dozens of terms and expressions in Qoheleth bear a unique meaning, different from that assigned them outside the book. While many scholars have contributed to the joint effort to reconstruct this peculiar lexicon, very few have attempted to account for the phenomenon itself. As will be shown below, these lexical peculiarities are likely to represent a deliberate attempt on the part of the book’s author to create a personally customized vocabulary. This linguistic project is central to the understanding of the book’s language and thought.

Two exceptional references to this aspect of Qoheleth’s language are found in Martin Hengel’s seminal work on Hellenistic Jewry and in Peter Machinist’s study of fate in Qoheleth.Footnote 8 Hengel remarks that the book of Qoheleth is characterized by Hellenistic thinking patterns that require new forms of expression. These include the assignment of novel meaning to existing lexemes, especially the verbal root ר”ות and the abstract nouns הרקמ, ןורתי, and קלח. The terms הרקמ and קלח as reflections of a personal terminology are further discussed by Machinist, who portrays the processes of abstraction involved in the creation of these expressions. Machinist shows how these produce the semantic fields of fate and time in Qoheleth and inspire the assignment of special meanings to at least five key terms in the book: הרקמ, קלח, השעמ, ןובשח, and םלוע. Associating this tendency with other unique characteristics of Qoheleth, Machinist links it especially with Qoheleth’s awareness of the reasoning process involved in his rational thinking.Footnote 9

Building on these pioneering works, the present paper seeks to evaluate Qoheleth’s language as a philosophical initiative. I will demonstrate how the attempt to create a personal idiom goes beyond the specific terms and semantic fields identified by Hengel and Machinist, demonstrating itself practically throughout the entire scope of Qoheleth’s lexicon. This, in turn, calls for a new appreciation of Qoheleth’s vocabulary as a means for understanding the book’s unique thought.

Qoheleth the Philosopher

The book of Qoheleth is the only biblical book that is essentially philosophical. Its concern lies with abstract, contemplative issues such as the purpose of life, the essence of death, and the problem of free will. To be sure, other biblical books are also interested in theology and ideology, but these always take a figurative form—prophecy, law, narrative, historiography, wisdom, psalmody, and so on.Footnote 10 Thus, the problem of evil is discussed in the book of Job through the concrete story of a pious sufferer. The issue of the human-divine relationship is dealt with in historiographical books through the prism of Israelite history. Civil, social, and religious values are discussed via biblical law. It is only in Qoheleth that abstract problems are appreciated for what they are—theoretical issues.Footnote 11 Rather than concretizing the issue of life’s meaning, Qoheleth attempts to generalize it:

מה יתרון לאדם בכל עמלו שיעמל תחת השמש

What benefit is there for a man in all the toil he performs under the sun? (Qoh 1:3)Footnote 12

The idea that generalization is a trademark of philosophical thinking was suggested by Greek philosophers themselves. It was Aristotle who ascribed a philosophical quality to earlier thinkers who attempted to define the “principle of all things”—that is, to generalize phenomena.Footnote 13

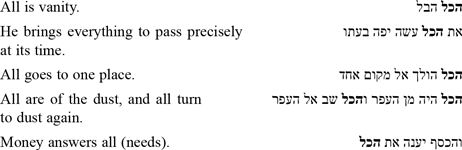

An important contribution to the appreciation of Qoheleth’s interest in the totality of phenomena was made by Yehoshua Amir.Footnote 14 Amir has noted that Qoheleth’s author is the only biblical thinker who seeks to characterize הכל “everything”—that is, to capture by way of induction the basic principles that govern reality. For instance:

As Amir shows, a similar tendency to define “everything” can be observed in pre-Socratic philosophy. It is noteworthy that the word כל is the most frequent term in Qoheleth, occurring 90 times in the book—far more than central terms such as הבל,אני, and עמל.Footnote 15 Qoheleth thus places הכל at the center of his thought. Rather than understanding certain details of reality, he is interested in capturing it as a whole.

The author’s personal fondness for הכל may account for an intriguing grammatical irregularity attested only in Qoheleth. The term כל in the book is sometimes applied to a group containing only two items. Compare the following examples:Footnote 16

החכם עיניו בראשו והכסיל בחשך הולך וידעתי גם אני שמקרה אחד יקרה את כלם

The wise man has his eyes in his head, while the fool goes about in darkness. And yet I perceived that the same fate befalls them all [= both]. (Qoh 2:14)

אל תהי צדיק הרבה ואל תתחכם יותר. . . אל תרשע הרבה ואל תהי סכל . . . טוב אשר תאחז בזה וגם מזה אל תנח את ידך כי ירא אלהים יצא את כלם

Be not overly righteous, and do not make yourself too wise…. Be not overly wicked, neither be a fool…. Better that you take hold of the one, and from the other withhold not your hand, for he who fears God fulfills them all [= both]. (Qoh 7:16–18)

את הכל ראיתי בימי הבלי יש צדיק אבד בצדקו ויש רשע מאריך ברעתו

I have seen everything [= both things] in my fleeting life: sometimes a righteous man perishes in his righteousness, and sometimes a wicked man lives long in his wickedness. (Qoh 7:15)

כי מקרה בני האדם ומקרה הבהמה ומקרה אחד להם כמות זה כן מות זה ורוח אחד לכל

For the fate of humans and the fate of animals is the same; as the one dies, so dies the other. They all [= both] have the same soul. (Qoh 3:19)

This exceptional usage—unknown in Biblical or in post-Biblical Hebrew—may perhaps reflect the author’s increased interest in כל as a concept and his desire to generalize concrete phenomena into an encompassing statement regarding totality. These factors seem to have contributed to the author’s tendency to use the term כל, with its all-inclusive connotation, even in cases where this usage creates a logical inaccuracy.

Another interesting indication of the philosophical nature of the book of Qoheleth is the arena where the drama takes place, referred to in the book as לבי “my heart.”Footnote 17 In biblical terms, the heart is the locus of human cognition, including consciousness, thinking, and emotion. External reality, where Qoheleth the king establishes an extravagant court (2:1–11) or where the rich mistreat the poor (4:1–3), is secondary in importance to the impression left by these events on Qoheleth’s mind. There is no other biblical book whose plot, so to speak, takes place solely within the speaker’s mind. Qoheleth’s philosophical discussion requires the use of abstract terminology.

The basic tool kit of any philosopher consists of conceptual phrases such as time, space, cosmos, humanity, meaning. Yet the Hebrew that lay at Qoheleth’s disposal contained little abstract vocabulary. The two Hebrew varieties available to him—Biblical Hebrew and Mishnaic Hebrew (or a predecessor thereof)—were both characterized by a figurative language that sought to present the world in concrete patterns.Footnote 18 Paving a pioneering way in the realm of thought, Qoheleth’s author had to create a terminology capable of expressing this new mode of contemplating existence. In what follows, I suggest that this specific need for a personally customized philosophical idiom shaped Qoheleth’s language to no less a degree than its linguistic environment. To establish this argument, I shall first examine in detail one test case, namely, the phrase תחת השמש. Other examples, with brief clarifications, will then follow.

The Case of תחת השמש

Research into this expression has usually focused on understanding the meaning of the phrase and revealing its origin.Footnote 19 The present discussion seeks to shift this traditional focus towards tracing the dynamics that gave rise to the choice of this specific term in order to load it with a personally customized meaning.

Occurring twenty-nine times in Qoheleth,Footnote 20 תחת השמש “under the sun” is one of the most important expressions in the book. It refers to the arena where human existence takes place—the laboratory in which Qoheleth makes his philosophical observations. Yet תחת השמש is defined by specific boundaries: rather than simply “world,” the phrase signifies the domain of living creatures, as opposed to the sphere of the dead—Sheol.Footnote 21 This specific meaning is best exemplified in cases where these two realms are contrasted:

וטוב משניהם את אשר עדן לא היה אשר לא ראה את המעשה הרע אשר נעשה תחת השמש

But better than either is he who has not yet been and has not seen the evil deeds that are done under the sun. (Qoh 4:3)

כי החיים יודעים שימתו והמתים אינם יודעים מאומה ואין עוד להם שכר כי נשכח זכרם

גם אהבתם גם שנאתם גם קנאתם כבר אבדה וחלק אין להם עוד לעולם בכל אשר נעשה תחת השמש

For the living know that they will die, while the dead know nothing, and no longer have reward, for their memory is forgotten. Their love and their hatred and their envy have already perished, and they never more have a portion in all that is done under the sun. (Qoh 9:5–6)

Semantically, then, the specific term תחת השמש makes sense in its context: it nicely excludes the dark Sheol, where no sunlight penetrates. Yet what is the origin of this peculiar phrase? Outside Qoheleth, תחת השמש is very difficult to find. It is unknown in Biblical Hebrew, post-Biblical Hebrew, and contemporary Aramaic. The closest parallels appear in a curse formula documented in several ancient Near Eastern languages: “May he not live under the sun” or “May he have no progeny under the sun.”Footnote 22 Directed against foreign armies, grave robbers, and so on, this curse is currently known from several examples in Phoenician, Elamite, Urartian, and peripheral Akkadian.Footnote 23 The Phoenician occurrences, appearing on the sarcophagi of two fifth-century BCE kings—Tabnit of Sidon and his son Ešmunazar—are especially relevant to this discussion:

אל יכנ לכ זרע בחימ תחת שמש ומשכב את רפאמ

May you have neither living progeny under the sun nor proper burial along with the rp’m.Footnote 24

אל יכנ למ שרש למט פר למעל ותאר בחימ תחת שמש

May they have neither root below nor fruit above, nor property in life under the sun.Footnote 25

Most scholars conclude their discussion of תחת השמש with references to these sources, which attest to its pan-Near Eastern nature.Footnote 26 Yet one question that is essential to the phrase’s proper understanding is very rarely asked: What led Qoheleth’s author to borrow an apparently uncommon, technical term whose usage is limited to the narrow genre of royal curse formulas?Footnote 27

The choice is even more puzzling in light of the fact that Biblical Hebrew offers the author at least two alternatives for תחת השמש in the sense of “world”: תחת השמים “under the heavens” and הארץ “earth.” Both phrases are used in Biblical Hebrew to denote “world.” See, for example:

ואני הנני מביא את המבול מים על הארץ לשחת כל בשר אשר בו רוח חיים מתחת השמים כל אשר בארץ יגוע

For My part, I am about to bring the Flood—waters upon the earth—to destroy all flesh under the heavens in which there is breath of life; everything on earth shall perish. (Gen 6:17)

ויאמר יי אל משה כתב זאת זכרון בספר ושים באזני יהושע כי מחה אמחה את זכר עמלק מתחת השמים

And the Lord said to Moses, write this for a memorial in a document, and rehearse it in the ears of Joshua, that I will utterly eradicate the name Amalek from under the heavens. (Exod 17:14)

Interestingly, the author is familiar with these terms, and uses them, albeit sporadically. תחת השמים occurs only three times in the book. One example is:

ונתתי את לבי לדרוש ולתור בחכמה על כל אשר נעשה תחת השמים

And I set my heart to investigate and explore out by wisdom all that occurs under the heavens. (Qoh 1:3)

The equivalent term ארץ in the same sense occurs five times. For instance:

כי אדם אין צדיק בארץ אשר יעשה טוב ולא יחטא

For there is no man on earth so righteous that does only good and never sins. (Qoh 7:20)

The author obviously finds neither of these terms appropriate for the specific philosophical notion he has in mind, a notion more accurate than the general concept “world.” Instead, he opts for the more exotic, uncommon phrase תחת השמש. It is precisely the limited distribution of תחת השמש and its narrow technical meaning that makes it semantically “available,” enabling its adaptation into a novel, personal concept.

Similar dynamics of utilizing terms that are conceived as “available” for semantic reloading are discernable in other core terms of Qoheleth’s personal lexicon. Hereafter, I shall refer to this dynamic as the utilization of semantic availability. Semantic availability may result from various factors, such as limited distribution, narrow technical meaning, and foreign origin.

Additional Cases of Personally Customized Terms

The above analysis of תחת השמש may shed new light on the dynamics that gave rise to Qoheleth’s personal philosophical lexicon. These involve generalization, abstraction, conceptualization, and/or specification of existing terms. The collection of terms that underwent this deliberate semantic shift includes well-known Hebrew words as well as rare or borrowed ones. In the latter case, utilization of semantic availability is discernable. The phrases listed below, all serving as key terms in the book of Qoheleth, are prominent examples of these semantic mechanisms.

-

1. יתרון: Occurring ten times in Qoheleth,Footnote 28 this term designates the profit gained by a deed or activity, either when examined in and of itself or when compared with another deed.Footnote 29 יתרון thus refers to one of Qoheleth’s central objects of research, as he attempts to discover whether there is anything worthy of doing, knowing, or having. Judging by our currently available sources, the term was barely known, if at all, in contemporary Hebrew.Footnote 30 It was probably borrowed from Aramaic, where it is fairly documented in various dialects. The Aramaic יותרן/יתרן may signify “abundance, excess (sometimes monetary), remainder, or surplus.”Footnote 31 Based on these meanings, the author creates a personally designed Aramaism to convey the philosophical concept of “material or mental benefit of a deed or activity.”Footnote 32 The principle of semantic availability is at play here, albeit in a slightly different form than that found in תחת השמש. There, the semantic availability is due to the narrow generic usage of the expression; here, it is born out of the foreignness of the phrase, which makes it free to bear a desired philosophical meaning.

-

2. עמל: In postexilic Hebrew, this term refers to “labor, toil” or, metonymically, to possessions accumulated through labor.Footnote 33 In Qoheleth, these common meanings are generalized and conceptualized. עמל in Qoheleth refers to various manifestations of life’s mental, physical, and social strains.Footnote 34 When referring to property, it is associated with the tiresome toil that has produced it. In half its occurrences (11 of 22), עמל is preceded by Qoheleth’s favorite particle, כל. The phrase כל + עמל usually means the “total sum of efforts and toil during one’s life” or “total accumulated assets.” Qoheleth thus uses this term to designate two of the book’s most important objects of investigation: human deeds and property.Footnote 35 The dull connotation of עמל implies that these are not only futile but also tiresome and irritating.

-

3. הבל: This is Qoheleth’s most important key term, constituting the book’s leitmotif: the problem of life’s meaning(lessness).Footnote 36 Its central place in Qoheleth’s thought has made it equally prominent in modern scholarly discussions, the result being a variety of different modern definitions of the term.Footnote 37 For the sake of the current discussion, however, suffice it to say that the term is used in Qoheleth to describe the futility of human existence, including nuances that derive from Qoheleth’s specific patterns of thought, such as absurdity and injustice. This reflects a deliberate and systematic adaptation of a term whose original meaning is much simpler, usually referring to “breath,” “vanity,” or “lie.”

-

4. רעות רוח ;רעיון רוח:aרעות and רעיון are pure Aramaic terms that, like יתרון, were probably not borrowed into any Hebrew variety of the time. Qoheleth’s author seems to have adopted them directly from Aramaic into his own Hebrew, possibly utilizing their semantic availability as foreign words. The Aramaic term רעות means “will, wish.” In several Aramaic dialects, רעיון bears a very similar meaning.Footnote 38 In Qoheleth, רעות רוח/רעיון רוח conveys the concept of “useless pursuit or striving.”Footnote 39 The terms may also appear in the hendiadys הבל ורעות רוח or הבל ורעיון רוח, in which case they are colored by the various meanings of the core term הבל discussed above.Footnote 40 By creating the expressions רעות רוח and רעיון רוח on the basis of contemporary Aramaic, the author reinforces the concept of the futility of human ambition.

-

5. מקרה: As noted above, this term was discussed by Hengel and more thoroughly by Machinist as an example of Qoheleth’s personal lexicon. The semantic shift at play is clearly visible here. This noun is rarely found in ancient Hebrew. In biblical books outside Qoheleth it only occurs three times, with the meaning “incidental event.”Footnote 41 In postbiblical varieties, it does not function as a living term, appearing only in biblical quotes or paraphrases. As explained above, rarity produces semantic availability, here utilized by Qoheleth’s author to create a term relating to death, a theme in which he is greatly interested. The author makes מקרה a common phrase in his book, carrying the specific meaning of “death as the inescapable fate of all living beings.”Footnote 42

-

6. חלק: The original biblical meaning of this word is “share, allotted portion (of a land, heritage, etc.).”Footnote 43 As adapted by Qoheleth, it conveys the “lot of each human being while living on earth, as allocated to him or her by God.” This may include both possessions and the pleasure taken in them.Footnote 44 Qoheleth often depicts one’s חלק as transient and temporary, stressing the unequal nature of the חלק’s divinely initiated distribution.Footnote 45 The former characteristic links חלק with the issue of death; the latter is related to the problem of justice. חלק is thus an essential term, supplying the author with a higher degree of elaboration and precision when discussing the crucial philosophical problems of death and (in)justice.

-

7. אכ”ל ושת”ה:Rather than referring to the concrete actions of eating and drinking, this syntagm is used in Qoheleth as a code for the carpe diem ethos that is central to the book’s thought. The meaning of אכ”ל ושת”ה in the book is approximately the “successful utilization of one’s assets for the sake of pleasure while still on earth.”Footnote 46

-

8. שהיה and שיהיה: The root הי”ה is very common in all Hebrew dialects. The forms שהיה and שיהיה literally mean “that which has been” and “that which will be,” respectively. In Qoheleth, however, they are employed to denote the abstract categories of “past” and “future,” probably to compensate for the lack of relevant terms in contemporary Hebrew.Footnote 47

-

9. תו”ר and סב”ב: These two motion verbs are assigned an abstract cognitive meaning by Qoheleth’s author. The root תו”ר originally denotes “seek out (physically).” In Qoheleth, however, it is used to express the cognitive action of enquiring.Footnote 48 The root סב”ב originally means “to turn (physically).” Qoheleth likewise employs it in the sense of “turn to another line of thinking”; “turn around in search for meaning.”Footnote 49 The author hereby fills the need for verbs that would describe the cognitive activity of the philosopher.

-

10. שמ”ח,שמחה and רא”ה בטוב: As Michael Fox has shown, the root שמ”ח in Qoheleth does not denote joy or happiness.Footnote 50 Rather, it usually refers to sensual pleasure, or—metonymically—means and accessories that yield pleasure.Footnote 51 This specific connotation is not unique to Qoheleth. Biblical Hebrew often assigns the root שמ”ח a similar meaning, especially when associating it with feasting or wine drinking.Footnote 52 Biblical Hebrew, however, does not tend to differentiate between sensual enjoyment and happiness, using the root שמ”ח to convey a variety of combinations of these elements. Only very rarely does the Bible use שמ”ח to refer to enjoyment devoid of authentic happiness.Footnote 53 In Qoheleth, the latter nuance is predominant. The author confines the root שמ”ח to conveying the idea of purely sensual pleasure or satisfaction. In Qoheleth’s Hebrew, the distinction between happiness and sensual pleasure becomes crucial. Often lacking any joy, Qoheleth’s שמחה is a partial and temporary compensation for the existential meaninglessness that troubles him.Footnote 54

A similar process can be identified in the case of רא”ה בטוב. Whereas Biblical Hebrew uses this expression to denote happiness and longevity,Footnote 55 in Qoheleth it serves as a synonym for שמ”ח—that is, another signification of sensual pleasure.Footnote 56 The semantic shift in this case is slight, based on the reinforcement of an existing Biblical Hebrew meaning. Its importance lies in the fact that it exemplifies how Qoheleth’s author standardizes and consolidates the meaning of specific terms in light of their existing semantic fields in order to create a specific desired nuance.

The eleven cases discussed above exemplify a deliberate linguistic endeavor. Shifting the semantic fields of certain terms, Qoheleth’s author reinvents them as personal expressions in accordance with his unique philosophy. Even when good Biblical Hebrew equivalents are at hand, he often opts for other, less well-known ones and assigns them a philosophical valence. In so doing, he occasionally takes advantage of linguistic availability—the foreignness, rareness, or technical usage of certain terms that seem to make them better suited, in his mind, to bear newly created meanings. In other cases, he loads well-known Hebrew terms with novel significations. As it turns out, this process of deliberate adaptation is most blatantly at play when it comes to core terms in Qoheleth’s philosophy. Here, the need for personally customized lexemes is most pressing. Taken together, Qoheleth’s neologisms constitute a personal idiolect, carefully designed to convey his unique thought.

Qoheleth’s Philosophical Language: Sociolect or Idiolect?

At this point the question should be raised whether all the examples of special meanings discussed here may be ascribed to a specific variety of Proto-Mishnaic Hebrew spoken in the author’s environment. Put otherwise, is it possible that, rather than a deliberate innovation of an individual mind, we are dealing here with traces of a Hebrew variety unknown to us—be it a dialect, a sociolect, or a vernacular—in which all these specific meanings and connotations were considered standard?

This alternative theory, while not impossible, is rather unlikely for several reasons. First, the specific meanings assigned in Qoheleth to the terms under discussion are in complete agreement with the themes that stand at the focus of the book’s thought, especially the problem of life’s meaning in the shadow of death. As shown above, the specific connotations assigned to individual terms often convey the precise concept of Qoheleth regarding the relevant issue. Designated meanings such as the “material or mental benefit of a deed or activity” for יתרון or the “lot of each human being while living on earth, as allocated to him or her by God” for חלק can hardly reflect a broad idiomatic usage. These are theologically specific, personally created expressions.

To these considerations, we may add an insight regarding dialectical dynamics in Second Temple Hebrew. Linguistic study of Second Temple Hebrew corpora has demonstrated that, despite their linguistic diversity, the various Second Temple varieties still share a great deal of their traits. The book of Qoheleth is itself a good example of the linguistic overlap among the various corpora: dozens of linguistic features found in Qoheleth can be classified as late on the basis of parallels found in Mishnaic Hebrew, Ben-Sira Hebrew, Qumran Hebrew, contemporary Aramaic sources, and other corpora. Such overlap is lacking, however, when it comes to philosophical phrases like the ones discussed above. None of these terms bears the same meaning in any First or Second Temple Hebrew corpus known to us. Were Qoheleth’s philosophical lexemes a standard feature in any specific variety of the time, one would expect them to occur, even sporadically, in one or more of the relevant corpora. The best way to account for this state of affairs is to assume that while many Late Biblical Hebrew features of Qoheleth reflect an existing linguistic environment, the book’s peculiar philosophical terminology is idiolectal in nature, reflecting a deliberate attempt to create a personally customized lexicon.

The Limits of Qoheleth’s Linguistic-Philosophical Project: The Concept of Infinity

Qoheleth’s lexical endeavor often comes at the expense of the richness of style. Unlike the biblical poets, who employ a diverse, vivid lexicon, Qoheleth’s writing, with its aspiration for conceptual accuracy, is often dictated by the fixed range of his personally created terms. To illustrate the scope of this phenomenon, I would like to examine briefly a case where the author does not adopt philosophical phraseology:

כל הדברים יגעים לא יוכל איש לדבר לא תשבע עין לראות ולא תמלא אזן משמע

All things are constantly laboring: No one is able to utter it, the eye is not sated with seeing, nor the ear filled with hearing. (Qoh 1:8)

This verse presents the conclusion Qoheleth draws from his observation of the cyclical movement of four natural elements: the earth (1:4), sun (1:5), wind (1:6), and water (1:7).Footnote 57 From these he concludes that “All things are constantly laboring.”Footnote 58 That is, all elements, bodies, and items in the cosmos are in constant motion. Because this motion never ends, “no one is able to utter it”: the endless movement cannot be exhausted by words. Nor can it be fully perceived by human senses: “the eye is not sated with seeing nor the ear filled with hearing.”

According to this interpretation, Qoheleth seeks to describe here—in a lengthy, poetic style—the concept of infinity. This reading finds support in 4:8, where the phrase “the eye is not sated” occurs again with the same meaning:

ואין קץ לכל עמלו גם עינו לא תשבע עשר

There is no end to all his wealth and his eyes are never sated with riches. (Qoh 4:8)

The expression “his eyes are never sated” parallels the phrase “there is no end,” both referring to the infinite quantity of the wealth described.Footnote 59

We may conclude that in attempting to describe the concept of infinity, Qoheleth’s author opts for a collection of poetic metaphors rather than a fixed technical term. In addition to the term אין קץ “there is no end,” occasionally used throughout the book,Footnote 60 he uses metaphorical depictions such as “the eye is not sated” and “the ear is not filled.” It seems that unlike other thinkers, Qoheleth’s author does not regard infinity as an essential philosophical notion. Nor does he seem interested in exploring infinity as a concept—at least not to the extent of requiring a fixed term. He is therefore content to use traditional biblical modes of expression—metaphorical, figurative phrases—rather than philosophically precise ones. The linguistic project of creating a personal idiolect therefore seems to be limited to core issues of the book’s thought.

Qoheleth’s Philosophical Language: Some Implications

The linguistic initiative described here may have broader implications for the study of Qoheleth and beyond. While a full discussion of these is beyond the scope of the current paper, I would like to refer briefly, by way of conclusion, to three derivative insights relating to the fields of Jewish intellectual history, the philosophy of language, and biblical studies—each of which demands further study.

The linguistic initiative discussed in this paper is comparable with similar tendencies exhibited by thinkers and philosophers in various times and places. Of special interest is the Hebrew philosophical lexicon created by medieval Jewish scholars in an effort to create a designated vocabulary to express their Neo-Aristotelian ideas.Footnote 61 This project bears surprising similarities to the mechanisms identified above in Qoheleth. Maimonidean scholar Alfred L. Ivry describes this medieval linguistic endeavor as follows:

The Hebrew origins of the new words often have but tangential significance for the new meanings assigned them, meanings which are Greek in origin. In this fashion the Hebrew translation movement both attached and severed itself from its own sources, creating a philosophical language in Hebrew which was a distinct novum in that language, though not a creatio ex nihilo…. The Hebrew translation movement found the words with which to give voice to a philosophical view of the world.Footnote 62

The relationship between the semantic dynamics typical of Qoheleth’s project and those of medieval Jewish scholars, as well as those reflected in similar linguistic projects from other cultural environments, have yet to be studied.

Examined from a broader cultural-linguistic perspective, the fascinating interrelation between thought and language traced here may be of value for the two hundred-year-old discussion of linguistic relativity conducted by cognitive linguists and philosophers of language. This field concerns the question of whether—and, if so, to what extent—one’s language molds one’s patterns of thought. From the works of such influential thinkers as Wilhelm von Humboldt, Franz Boas, Edward Sapir, and Benjamin Lee Whorf through to recent studies, scholars are still seeking to clarify the delicate relation between language, thought, and cultural patterns. Our findings may present a modest contribution to this discussion since, in Qoheleth’s case, the influence is clearly bidirectional, language and thought sustaining one another. The introduction of novel thinking patterns gives rise to new linguistic structures, which in turn expand the intellectual space in which innovative thinking can take place. The reciprocal system reflected here is in line with recent trends in the field of cognitive linguistics. Having long abandoned the idea of linguistic determinism, these acknowledge the complex relationship between language and thought, attempting to develop more nuanced models to explain it.Footnote 63

Turning back now to the field of biblical studies, the current study also bears on the intellectual-historical context of the book. As Hengel and Machinist have already demonstrated, the peculiar dynamics that gave rise to Qoheleth’s idiolect cannot be fully understood outside their proper historical context. The phenomena and characteristics described above all seem to reflect a Hellenistic zeitgeist. The philosophical-linguistic project described here apparently results from the introduction of Greek thought into the Jewish world during the third century BCE. Our findings thus reinforce the common scholarly hypothesis that the book’s author was an educated Jew living in the early Hellenistic period, who found himself challenged and inspired by Greek thought. The very concept of philosophy, with the thinking patterns and abstract language it requires is, of course, typically Greek. The same is true, as shown above, of the attempt to define totality. Qoheleth’s philosophical language may thus be best described as the outcome of the fertile contact between an older Israelite tradition, a newly introduced Greek culture, and the personal, creative mind of an individualist.