1 Introduction

EU law has had a substantial impact in the development of antidiscrimination law in Member States (‘MS’).Footnote 1 Crucially, it has influenced both substantive provisions and enforcement mechanisms. After the entry into force of the Treaty of Amsterdam, the EU was able to adopt the ‘Racial Equality Directive’ (RED) and the ‘Framework Equality Directive’ (FED).Footnote 2 Among other merits,Footnote 3 these Directives expanded the list of protected groundsFootnote 4 and introduced novel enforcement requirements. In particular, the RED established a duty to set up Equality Bodies (EBs) in the field of ethnic-origin or racial discrimination.Footnote 5 This duty was later extended to other – although not all Footnote 6 – discrimination grounds, namely sex and nationality discrimination for mobile workers.Footnote 7

Whilst the initial transposition of the EU mandate to set up EBs was ‘fraught’ and ‘uneven’,Footnote 8 it eventually led to the creation of a wealth of EBs and/or the consolidation of existing ones.Footnote 9 However, this trend shifted with the 2008 financial and economic crisis, which led to budget cuts for many EBs as well as various changes in their institutional architectureFootnote 10 that put various EBs in difficulty to perform their functions effectively (Ammer et al., Reference Ammer2010, pp. 78, 141–142; Equinet, 2012). Following various EU Directives’ implementation reportsFootnote 11 and a campaign launched by the European Network of Equality Bodies (‘Equinet’) (2016), it became obvious that the divergences between national EBs and the challenges they faced were partly due to the vague provisions contained in EU Directives and that clearer EU standards for EBs were needed. To encourage the design of more effective EBs, the EU adopted in 2018 the ‘Commission Recommendation on Standards for EBs’ (‘the Recommendation’).Footnote 12

This paper deals precisely with EBs as one of the tools available to policy-makers to enforce antidiscrimination law.Footnote 13 The central argument made here is that EBs can be crucial institutions to effectively ‘respond’ to discrimination, if appropriately designed and resourced. The paper focuses on ‘promotion-type’ EBs (i.e. those mainly seeking to support victims, raising awareness and promoting good practice)Footnote 14 with competences in the field of ethnic-origin or racial discrimination.Footnote 15

The starting point of the analysis are international benchmarks on EBs, which are used to draw a ‘Responsiveness Framework’ that sets the key dimensions for equality watchdogs to effectively support individuals’ reactions to ethnic-origin or racial discrimination and to promote equalityFootnote 16 in this field (section 2). This framework is then used to prove the RED's inability to yield national implementation approaches leading to the design of responsive EBs (section 3). This is further demonstrated with a case-study that applies the responsiveness dimensions to the British and the Spanish EBs (section 4). The paper concludes by briefly considering the standards set by the 2018 Recommendation and its potential to encourage the design of more responsive EBs (section 5).

From a methodological perspective, this work combines a ‘law in the books’ and ‘law in action’ approach. The former is based on the study of international instruments, as well as EU law and national law, whereas the ‘law in action’ analysis builds on the comparison between the British and Spanish EBs. This case-study draws on semi-structured interviews of key national experts and intermediaries in close contact with EBs and actual or potential victims of discrimination,Footnote 17 grey literature reports and reliable information published by public bodies, national EBs and Equinet.Footnote 18

Before embarking on further discussion, a few terminological clarifications are needed. The term ‘responsiveness’ has been used in the literature with different meanings. Yesilkagit and Snijders (Reference Yesilkagit and Snijders2008) consider that EBs are ‘responsive’ when they respond to all democratic preferences and to the demands of ‘multiple political stakeholders’.Footnote 19 In this paper, that concept of responsiveness is embedded in the ‘independence’ dimension.Footnote 20 For our purposes, the term ‘responsiveness’ is borrowed from Fineman's idea of the ‘responsive state’ (i.e. that state institutions have the onus to ‘respond’ to human vulnerability), which she developed in the context of her vulnerability theory (Reference Fineman2008, pp. 19–22). That concept has been taken forward by capability scholars, like Mackenzie,Footnote 21 who alerts that the idea of vulnerability should not be used to develop ‘coercive and objectionably paternalistic social relations’ (Mackenzie, Reference Mackenzie and Mackenzie2014, p. 34). She suggests that, in a theory of justice, the state's ‘duty to protect must be informed by the overall background aim of enabling the development of … autonomy, wherever possible’ (Mackenzie, Reference Mackenzie and Mackenzie2014, p. 35). Accordingly, the role of public institutions should be to help ‘foster the development of the autonomy competences and capabilities necessary for functioning as an equal citizen in a democratic state’ (Mackenzie, Reference Mackenzie and Mackenzie2014, p. 34, citing Anderson, Reference Anderson1999, p. 316). Building on these ideas, the expression ‘responsiveness’ is used in this paper to argue that the state's duty to tackle discrimination and promote equality can more effectively be pursued relying on EBs. Provided that these institutions are appropriately designed and resourced, they can be key tools to effectively ‘respond’ to discrimination by both addressing it reactively, once it has occurred, and proactively, through strategies to promote equality. Thus, EBs can not only strategically act and campaign for equal treatment (‘top responsiveness’), but also support and empower vulnerable individuals to become more autonomous in fighting discrimination (‘bottom responsiveness’).

In this context, the term ‘effectiveness’ is used with a double meaning. First, it refers to strategies linked to ‘top responsiveness’ that work to promote equal treatment and maximise the prevention of discrimination (‘ex ante effectiveness’). Second, it evokes tools and approaches deemed to minimise the impact of discrimination once it has occurred (ex post effectiveness), which are connected to ‘bottom responsiveness’. Most European legal systems are strongly based on reactive and individual enforcement models (Bell, Reference Bell2008; Fredman, Reference Fredman2012) so, as the next section elucidates, the development of standards to boost EBs’ responsiveness (top/bottom) must incorporate these two types of effectiveness (ex ante/ex post) (Benedi Lahuerta, Reference Benedi Lahuerta2014).

2 The ‘Responsiveness Framework’ for the institutional design of EBs

To ensure that EBs are responsive to discrimination in a way that fosters vulnerable groups’ autonomy, their institutional design should ideally be approached looking at the actual issues arising at the grass-roots level. These issues, and the corresponding design of EBs, will naturally change according to the social context. Nevertheless, there are a number of ‘discrimination challenges’ that are widespread in many jurisdictions, like the lack of awareness about antidiscrimination legislation (FRA, 2017), the inability to recognise what is discrimination (Citizens' Advice Bureau interview, 6 June 2018; see Appendix) and/or how to take action against it (FRA, 2012; 2017), the persistence of systemic discrimination,Footnote 22 stigma (Solanke, Reference Solanke2017) and discriminatory biases (Alfinito Vieira and Graser, Reference Alfinito and Graser2015). It is also widely documented that individuals who feel discriminated against tend not to report those behavioursFootnote 23 due not only personal motives, but also for fear of retaliation,Footnote 24 mistrust in the legal systemFootnote 25 and lack of resources and/or understanding of complex legal terms and procedures.Footnote 26 It is also common ground that EBs can play a key role in promoting a better enforcement of antidiscrimination legislation and in addressing these challenges if they are appropriately designed and ‘they are given the necessary powers and resources’ (Kádár, Reference Kádár2018 p. 147).Footnote 27 Indeed, at the international level, there is a relatively broad consensus over the minimum standards that should be observed in EBs’ design to ensure that they are responsive to most of the common discrimination challenges.

This section re-evaluates and synthetises international EBs’ standards, placing emphasis on those dimensions that are crucial to achieving better EBs. These standards are used to build a ‘Responsiveness Framework’ that classifies ‘responsiveness dimensions’ into three groups, depending on whether they are relevant for ‘bottom responsiveness’, ‘top responsiveness’ or both (‘general responsiveness’). Each dimension includes several subdimensions summarised in Table 1 and discussed in detail in the remainder of this section.

Table 1. Responsiveness Framework for the institutional design of EBs

Source: Author's own elaboration.

The key sources considered to build this framework are benchmark documents issued by international bodies or agencies (i.e. the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI), the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights (CoE Commissioner), the UN, the EU Fundamental Rights Agency (FRA)) and by umbrella organisations representing EBs (i.e. Equinet).Footnote 28

2.1 General responsiveness

At the general level, it is necessary that EBs are able to act independently (Table 1 and section 2.1.1) and that they have enough resources to meaningfully carry out all their functions (Table 1 and section 2.1.2). Quite understandably, these two subdimensions will affect their performance at all levels, including their ability to empower and provide comprehensive assistance to individuals who feel discriminated against.

2.1.1 Independence

International instruments strongly emphasise the need for EBs to be independent. The concept of ‘independence’ is, however, fairly vague and lends itself to different interpretations.Footnote 29 To keep this framework relatively simple, all possible meanings of ‘independence’ have been included in just two dimensions, namely de jure and de facto independence (ECRI, 2018a, para. 2; CoE Commissioner, 2011, pp. 14–15). De jure independence demands that EBs’ governing bodies are appointed by and are accountable to the legislative and that appointment procedures are clear and ensure a diverse representation of (civil) society (Paris Principles, p. 1).Footnote 30 De jure independence also entails that appointments should be for a predetermined term and mandate (Paris Principles, p. 3); and appointees should enjoy ‘functional immunity’ to avoid coercion and ‘arbitrary dismissal’ (Paris Principles, p. 3; ECRI, 2018a, para. 24). On the other hand, de facto independence can only be guaranteed if EBs have powers to set their own priorities within their mandate and are able to manage their own resources, including their personnel. It is also crucial that they are not under the influence of the state or other external pressures.Footnote 31 If these benchmarks are met, EBs will be more likely to provide assistance freelyFootnote 32 and to respond to changing social needs by adjusting the resources allocated to different services.

2.1.2 Resources

Additionally, EBs need a certain level of resources to support at least a ‘critical mass’ of complainants along the full access to justice pathway (CoE Commissioner, 2011). Resources’ availability will vary from country to countryFootnote 33 and the levels needed will depend on variables like the breadth of the EBs’ mandate, the size of vulnerable groups, the levels of discrimination and the roles of other stakeholders. It is imperative, however, that EBs are allocated enough – human, technical and financial – resources to effectively perform all their functions (ECRI, 2018a; Equinet, 2016, p. 5)Footnote 34 and that they are protected against arbitrary or disproportionate budget reductions or against extensions of their mandates without a paralleled increase in resources (ECRI, 2018a).

2.2 Bottom responsiveness

Building on their independence and resource levels, EBs should offer a wide range of support services to alleged victims (Table 1, 2.B), particularly legal assistance and legal advice. Additionally, in contexts with high levels of underreporting, EBs’ accessibility will also be necessary (Table 1, 2.A) for good bottom responsiveness (CoE Commissioner, 2011, p. 17).Footnote 35

2.2.1 Accessibility

Accessibility includes at least two aspects. First, it is imperative that, through awareness-raising initiatives and outreach campaigns (Table 1, 2.A.i), EBs are ‘present’ with the most disenfranchised groups and that they build ‘sustained links’ with them (ECRI, 2018a). This can improve the understanding of what amounts to discrimination, contribute to build reciprocal trust and raise awareness about antidiscrimination rights and enforcement procedures. Furthermore, outreach work enhances the visibility of EBs and may empower individuals experiencing discrimination to take cases forward (CoE Commissioner, 2011, pp. 7, 17–18).

Second, accessibility requires lessening external barriers to access EBs’ services (Table 1, 2.A.ii), namely providing assistance through a wide range of channels, including online, e-mail, telephone and face-to-face options (ECRI, 2018a, para. 40). Ensuring that the location is easily accessible may entail ‘bridg[ing] physical distance to first contact points’ (FRA, 2012, p. 7) through the setting-up of local and/or regional premises (ECRI, 1997; 2018a; CoE Commissioner, 2011, pp. 17–18). Good accessibility equally requires adjusting services for diverse potential usersFootnote 36 and providing a confidential and free-of-charge serviceFootnote 37 in a language in which the complainant is proficient (ECRI, 2018a, paras 16, 40; CoE Commissioner, 2011, pp. 17–18; Equinet, 2016, p. 6). Ensuring that EBs’ personnel is as diverse as possible equally contributes to making a wider range of people feel welcome and to be perceived as accessible (ICHRP, 2005, pp. 16–17).

2.2.2 Support services for alleged victims

On its own, accessibility is not enough to ensure that EBs are responsive at the bottom; it is also essential that they support individuals who feel discriminated against (ECRI, 2018a, paras 10, 14). Ideally, EBs should offer a wide range of support services, including not only legal services, but also emotional and/or psychological support (FRA, 2012, p. 51; Table 1, 2.B.i-iv). The ability to do so will clearly depend on various factors (e.g. resources, staff skills), but simply an empathic attitude from support staff can empower individuals to lodge complaints or to overcome stressful adjudication procedures (FRA, 2012, pp. 51–52).

In terms of legal support, there is some terminological confusion over the services that EBs ought to offer. While it seems fairly clear that providing ‘legal assistance’ or ‘legal advice’ is different from hearing and investigating complaints,Footnote 38 the distinction between the expressions ‘legal assistance’ and ‘legal advice’ is more intricate, as they are used with different – yet sometimes overlapping – meanings. In fact, different EBs have interpreted these expressions in various ways.Footnote 39 Building on common-law concepts,Footnote 40 in this paper, ‘legal assistance’ refers to helping individuals exposed to discrimination by providing them with general information about the substantive and/or procedural aspects of the lawFootnote 41; this can be done by anyone with sufficient knowledge. Quite differently, providing ‘legal advice’ to someone requires the application of the law to a specific factual situation, traditionally by trained lawyers,Footnote 42 offering ‘professional judgment’ on the best course of action and acting on behalf of the client, if required (ABA, 2002, Rule 2.1). This distinction has been impliedly recognised by both the ECRI (2018a, para. 14a) and the CoE Commissioner (2011, p. 13). Indeed, the latter and most international bodies recommend that EBs provide both ‘legal assistance’ and ‘legal advice’. For instance, the ECRI (1997) suggests that the ‘support and litigation function’ of EBs should include, inter alia, providing ‘personal support and assistance … to secure [complainants] rights’ before the relevant institutions, representing complainants in legal or administrative proceedings and bringing cases in its own name (para. 10(a), emphasis added).

On the whole, therefore, responsive EBs should offer not only general support and legal assistance stricto senso, but also legal advice and, in strategic cases, they should also be able to initiate claims in their own name and to represent claimants before adjudicatory bodies so that the latter can ‘navigate and be supported along the full pathway for access to justice’ (Equinet, 2016, p. 5).

2.3 Top responsiveness

To effectively address discrimination general and bottom responsiveness is not enough. Discrimination is often the product of collective social forces, so EBs should also be equipped to take action at systemic level (Table 1, 3.A). To effectively do so, they should also co-ordinate their actions with other stakeholders (Table 1, 3.B).

2.3.1 Systemic action

As MacEwen (Reference MacEwen and MacEwen1997, p. 10) points out: ‘[u]nless [antidiscrimination laws] are accompanied by government policies and strategies which imbed the legislative provisions in a more holistic approach to discrimination, substantial change is unlikely to be effective.’ Indeed, aside from reactively supporting alleged victims, responsive EBs must have powers to promote equality and prevent discrimination.

EBs’ systemic action can include a diverse range of powers, but they may broadly be grouped around three clusters. First, they need to have powers to collect information to identify key issues to be addressed at the grass-roots level, such as to conduct inquiries and research ‘on their own initiative into all matters falling under their mandate’, both as regards individual and structural discrimination (ECRI, 2018a, para. 13.c–d; CoE Commissioner, 2011, p. 6). Their contact with people exposed to discrimination, either directly – through their support servicesFootnote 43 – or indirectly – through dialogue with non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and other organisationsFootnote 44 – can also be a valuable source of information (ECRI, 2018a, para. 13.b).

Second, EBs must be able to act on the issues identified thanks to the information gathered. At this stage, promotion action may range from launching campaigns to build awareness about antidiscrimination legislation and ‘a culture of compliance’ among employers, service providers and policy-makers (ECRI, 2018a, para. 13.e; CoE Commissioner, 2011, p. 6; Equinet, 2016, p. 4) to promoting good practices and positive action measures to address systemic discrimination, in both the public and private sectors (ECRI, 2018a, para. 13.e–f; CoE Commissioner, 2011, p. 13; Equinet, 2016, p. 4).

Finally, the two subdimensions just discussed should be complemented by an ‘advisory’ function,Footnote 45 so that EBs can use their expert knowledge to directly influence policy and legislation from the top. This should enable EBs to participate in consultation procedures and make recommendations regarding new policies and legislation, among other potential powers (ECRI, 2018a, para. 13.j; CoE Commissioner, 2011, p. 19; Equinet, 2016, p. 4).

2.3.2 Co-ordination

The co-ordination of EBs’ strategies and activities with other stakeholders can also be decisive to improve their responsiveness. In most jurisdictions, there will be an array of entities directly or indirectly involved in equality promotion and/or support to complainants, such as public institutions (e.g. Ombudsmen, Labour Inspectorates, Consumer Defence Bodies), employers’ associations, trade unions, NGOs and informal groups representing vulnerable communities (ECRI, 2018a, paras 13.b, 21; CoE Commissioner, 2011, p. 20). Co-ordination between EBs and these institutions is crucial to build a shared understanding of key issues to be addressed and create synergies, avoid duplication of activities and maximise impact.Footnote 46 EBs can even become ‘equality hubs’ leading networking efforts and helping to optimise the use of resources to achieve the common aspiration of promoting equality (CoE Commissioner, 2011, pp. 12, 18; Equinet, 2016, pp. 4, 16). Being in close contact with NGOs representing vulnerable groups can contribute to better educating the latter about their rights and enforcement pathways, to build reciprocal trust and to empower individuals to recognise discrimination and act against it,Footnote 47 thus fostering the autonomy of groups exposed to discrimination.

These top-level activities can also contribute to addressing discrimination at the bottom, and vice versa. For instance, at the bottom, EBs should support individual victims not only to address underreporting and challenge discrimination, but also to gain intelligence that can inform EBs’ activities at the top level (e.g. to approach employers to change systemic discriminatory policies, undertake strategic litigation or run awareness-raising campaigns in collaboration with other stakeholders). Thus, the three responsiveness levels are interrelated. Building on these principles, section 3 demonstrates how the vague provisions of the RED are likely to undermine EBs’ responsiveness.

3 The door left opened to unresponsive designs: the gaps of the RED

The crucial influence that EU 2000s’ Directives have had in the development of EBs across the EU should not be downplayed.Footnote 48 Despite some implementation and compliance problems, the Directives were the main driver for the setting-up of most of the EBs that are now place in MS (Van Ballegooij and Moxom, Reference Van Ballegooij and Moxom2018). Yet, their limits must also be acknowledged. This section analyses the rather elusive provisions of the RED to identify their gaps in relation to the Responsiveness Framework.

The RED itself clearly recognises the potential of EBs to respond to discrimination. Indeed, Recital 24 of the Directive states that

‘[p]rotection against discrimination based on racial or ethnic origin would itself be strengthened by the existence of a body or bodies in each Member State, with competence to analyse the problems involved, to study possible solutions [top responsiveness] and to provide concrete assistance for the victims [bottom responsiveness].’ (Emphasis added)

The EU Commission (2018) has also stressed that ‘[t]he best way to effectively implement and enforce [EU antidiscrimination legislation] is through the use of independent equality bodies’.

However, the RED equally notes that it only ‘lays down minimum standards’,Footnote 49 which leaves plenty of freedom at the implementation stage – so much so that MS may set up EBs in full compliance with the Directive by designing largely unresponsive EBs. This can be appreciated by applying the ‘Responsiveness Framework’ to the RED provisions.

First, the two key dimensions contributing to the general EBs’ responsiveness are being independent and having enough resources. The first striking feature of the RED is that it does not require that EBs are formally (de jure) independent. For instance, the Directive does not demand that national EBs are self-standing and/or have legal personality.Footnote 50 Accordingly, EBs may be embedded within national human rights’ institutions, or even within government departments.Footnote 51 The former is not necessarily a problem provided that the human rights institution enjoys formal independence,Footnote 52 but belonging to a government department can hinder a given EB's potential to use its powers and resources as it sees fit. On the other hand, the RED establishes that EBs should perform their assistance and advisory functionsFootnote 53 independently in practice (de facto).Footnote 54 This should lead to implementation designs that ensure that EBs undertake each of these functions in an independent manner. Yet, the lack of a formal independence requirement entails that EBs may lack organic and/or financial independence to take key decisions on their own, such as adopting its strategic plan or shifting resources between different areas.Footnote 55 This loophole is likely to undermine the responsiveness of EBs, unless national EBs’ designs go beyond the minimum RED standards.

Regarding the level of resources, the RED simply indicates that these functions may be performed by one or more bodies, or even by national human rights institutions,Footnote 56 without any reference to the need to allocate sufficient resources to EBs according to their size and powers, or to the need to protect these bodies against arbitrary budgetary reductions. Indeed, various surveys have found that the lack of staff and financial resources is one the most pressing challenges faced by EBs (Figure 1)Footnote 57 and the ‘most significant barrier’ to being effective and ‘realis[ing] their full potential’ (Crowley, Reference Crowley2018, p. 103).

Figure 1. Challenges faced by EBs at the national level.

Source: Adapted from EU Commission (Targeted Consultation 2018).

Note: The consultation scale had five possible answers, from which respondents had to choose one. For simplicity, 'considerable challenge', 'challenge' and 'somewhat a challenge' have been grouped under 'challenge'; 'not a challenge' and 'no opinion' have been omitted.

Second, at the bottom-responsiveness level, the RED does not lay any clear standard regarding accessibility. In terms of awareness-raising, the Directive only includes a general reference to the need to disseminate information about antidiscrimination legislation so that it is ‘brought to the attention of the persons concerned by all appropriate means throughout their territory’.Footnote 58 It could be argued that, as key players in equality promotion and the fighting of discrimination, EBs should be one of the ‘means’ used to disseminate that information through regular contact with vulnerable groups and outreach campaigns. Nevertheless, once again, the RED does not formally require so, and it does not demand either that external barriers to access EBs’ services are minimised.Footnote 59 Recent surveys confirm that these gaps have led to practical problems at the national level, such as the lack of awareness of EBs and/or antidiscrimination legislation (FRA, 2017) and the overwhelming lack of local or regional offices.Footnote 60

The RED is also very vague regarding another subdimension of bottom responsiveness, namely the type/s of support service/s that EBs should offer to individuals who feel discriminated against. The Directive simply establishes that EBs should ‘provid[e] independent assistance to victims of discrimination in pursuing their complaints about discrimination’, without any guidance as to what is meant by ‘assistance’ or how it should be provided.Footnote 61 This wording gives MS plenty of room to decide on these issues as they see fit.Footnote 62 Still, following a purposive interpretation of the RED's preamble (demanding that EBs provide ‘concrete’ and ‘practical’ assistance to victims)Footnote 63 and of the requirement to assist victims ‘in pursuing their complaints about discrimination’, it may be argued that EBs’ support services should help individuals to enforce their antidiscrimination rights in their specific case. Accordingly, having only a website with general information about how to get redress could be considered insufficient to meet the RED minimum standards. It seems, therefore, that EBs should provide, at least, legal assistance.Footnote 64 However, the vague wording of the RED and its preparatory worksFootnote 65 would probably not support interpreting ‘assistance’ as including legal advice or legal representation (Tyson, Reference Tyson2001; Jacobsen, Reference Jacobsen2010, pp. 88–89).

Third, if we turn our attention to the top-responsiveness dimensions, the RED includes some references to aspects relevant to taking systemic action against discrimination. Article 13(2) requires that EBs have powers to ‘[conduct] independent surveys concerning discrimination’ and to ‘[publish] independent reports and [make recommendations] on any issue relating to such discrimination’, but leaves the terms ‘surveys’, ‘reports’ and ‘recommendations’ open for interpretation.Footnote 66 For instance, it is unclear whether conducting surveys demands that EBs have investigatory powers to collect relevant dataFootnote 67 and whether the EBs should have powers to issue ‘recommendations’ at their own initiative or only upon the request of a governmental or legislative body.

Finally, regarding the co-ordination dimension, once again, the RED broadly encourages social dialogue (Art. 11) and dialogue with NGOs (Art. 12). Whilst EBs could be involved in the effective implementation of these articles, and would be particularly well placed to ‘encourage dialogue with appropriate non-governmental organisations which have … a legitimate interest in contributing to the fight against discrimination’,Footnote 68 the actual wording of these two articles does not require that EBs partake in or encourage these dialogues.

Various EU publications and grey literature studies attest how the vague RED standards have led to an exceptional diversity of interpretations and different implementation approaches across MS.Footnote 69 For example, the results of a 2018 targeted consultation show that the loopholes discussed supra have created various challenges for EBs, including the lack of staff resources, the lack of awareness of the existence of EBs and the lack of physical presence (see Figure 1).

Indeed, the 2018 Recommendation acknowledges these gaps and the consequent challenges,Footnote 70 and generally recognises that

‘[t]he text of the equality Directives leaves a wide margin of discretion to Member States on the structure and functioning of equality bodies. This results in significant differences … [and] sometimes leads to unsatisfactory access to protection for citizens, a protection which is unequal from one Member State to another.’Footnote 71

The next section delves deeply into two examples of national implementation to demonstrate how the broad margin of manoeuvre left by the RED has led to largely divergent implementation approaches and to designing EBs that are unresponsive at the bottom and/or at the top.

4 Comparing the British and Spanish EBs: unresponsive, with or without resources

This section compares the British Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) and the Spanish Consejo para la Eliminación de la Discriminación Racial o Étnica (CERED) against each other and against the ‘Responsiveness Framework’.Footnote 72 Through this comparative exercise, it becomes evident that both promotion-type bodies face contrasting challenges to respond to discrimination due to their different institutional designs.

To start with, their origin and competences are fairly different. The EHRC is a multi-ground body with powers regarding all grounds protected under the Equality Act 2010Footnote 73 and in the broader field of human rights.Footnote 74 On the other hand, the CERED is a single-ground equality body that only has powers in the field of race or ethnic discrimination.Footnote 75 Furthermore, whilst the EHRC was only set up in 2006, it partly builds on the expertise of its three predecessors.Footnote 76 Conversely, the CERED was established in 2010 in view of implementing the RED, so it is a ‘younger’ institution. Despite these differences, both are the designated ‘bodies for the promotion of equal treatment’ for the purposes of the REDFootnote 77 and should seek to be as responsive as possible to discrimination.

4.1 General responsiveness

As discussed supra, two general prerequisites that support EBs’ responsiveness are their independence and the level of resources available to perform their tasks (Table 1, 1.A and 1.B). Whilst neither the EHRC nor the CERED can be considered to enjoy full de jure independence given that they are both attached to a government department,Footnote 78 the EHRC's legal configuration safeguards de jure independence better than the CERED's set-up.Footnote 79 Indeed, the EHRC is an ‘independent arm's length body’Footnote 80 and a body corporate (Equality Act (EqA) 2006, s. 1) with legal personality and its own rights and responsibilities. In contrast, the CERED is a collegiate body embedded in a government ministry and lacks legal personality. Furthermore, the EHRC lays its strategic plan and accounts before parliament (DCMS and EHRC, 2015, paras 8.3, 11.1, 14.1) and is governed by a Chair and a board of Commissioners deemed to be independent from the government.Footnote 81 In contrast, 44 per cent of the CERED plenary members are directly appointed by government (or collegiate bodies under the latter's control).Footnote 82

In practice, however, neither the EHRC nor the CERED enjoys full de facto independence. The CERED does not have its own staffFootnote 83 and its budget is part of that same ministry.Footnote 84 Accordingly, even though it is for the CERED's plenum to establish its line of action,Footnote 85 the lack of its own resources poses great difficulties in doing so. Whilst the EHRC's budget is also determined by its sponsor government department,Footnote 86 the former has responsibility for the recruitment of its own staff (EqA 2006, Sch. 1, para. 7(3); DCMS and EHRC, 2015, para. 15.1)Footnote 87 and can set its own priorities through its three-year strategic plan (DCMS and EHRC, 2015, para. 7.1). However, the practical relevance of these powers is hampered by its financial dependence on the Government Equalities’ Office (GEO), which approves its spending ‘in relation to value for money only and not whether the EHRC should undertake the activity in line with its statutory powers and duties’ (DCMS and EHRC, 2015, para. 6, emphasis added).

Besides independence, responsive EBs must also have sufficient resources to perform all their tasks. The case-study EBs have very different resource levels: whereas, for the last three years, the EHRC's budget has been in the range of £22–23 million, the CERED's budget has always been under €700,000.Footnote 88 However, Britain has a larger population than SpainFootnote 89 and, as noted supra, the EHRC's mandate is also much larger than that of the CERED. For these reasons, a strict comparison of their resources is not advisable. However, it broadly seems that the larger financial resources of the EHRC could put this institution in a more advantageous position to perform its functions more effectively than for the CERED, and hence to be more responsive.Footnote 90

4.2 Bottom responsiveness

To assess the CERED's and the EHRC's bottom responsiveness, it is necessary to briefly introduce their general approach to support alleged victims of discrimination. Despite the CERED's lack of independence and modest resources, it has managed to establish a ‘low-cost’ support system based on a Network of Assistance (Servicio de Asistencia a Víctimas de Discriminación Racial y Étnica, hereinafter ‘SAV’ or ‘the Network’) formed by eight NGOs working in the field of racial discrimination,Footnote 91 including the co-ordinating one, Fundación Secretariado Gitano (FSG).Footnote 92 Unlike the CERED, the EHRC does not provide direct support to alleged victims anymore.Footnote 93 The latter's helpline, which provided legal assistance to complainants (EHRC, 2009), was externalised in 2012 under the label ‘Equality Advisory Support Service’ (EASS) due, mainly, to cost-effectiveness reasons (GEO, 2011, pp. 73–82). Therefore, the EHRC only currently engages in selected strategic litigation cases.

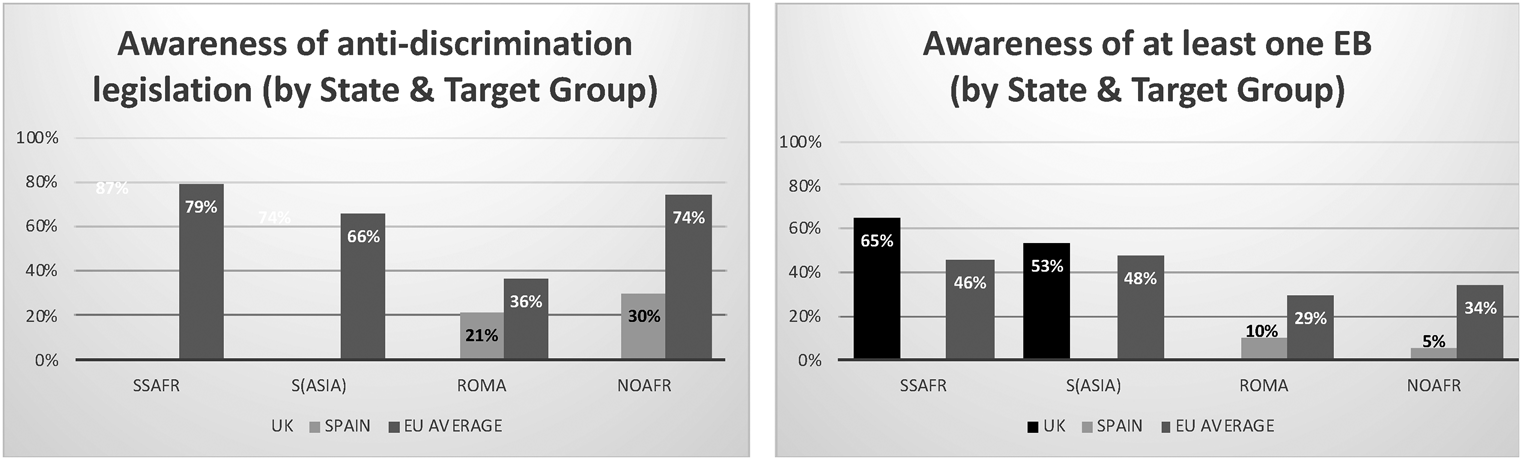

This brief overview of the CERED and the EHRC support services suffices to assess their performance against the accessibility dimension (Table 1, 2.A). As discussed earlier, to maximise accessibility, EBs should raise awareness about antidiscrimination rights, enforcement procedures and their support services. However, the efforts required may vary from country to country. For instance, the EHRC may have benefited from visibility campaigns undertaken in the 1990s by the former Commission for Racial Equality (CRE)Footnote 94 so, in a recent survey, 60 per cent of UK respondents were aware of at least one EB, whereas only 6 per cent of Spanish respondents were (FRA, 2017, p. 52). Awareness of EBs may in turn influence vulnerable groups’ awareness about antidiscrimination legislation, which, in the UK, is among the highest in the EU, whereas, in Spain, it is among the lowest (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Awareness of antidiscrimination legislation and Equality Bodies in the UK, Spain and the EU.

Source: Adapted from FRA (EU Midis II, 2017)

Indeed, the CERED has recognised that important efforts are still needed to improve its visibility and awareness about the services it provides (SAV, 2016, p. 71). Its Network has been trying to address this through active dissemination campaigns, such as by launching a new website, distributing more than 20,500 leaflets and holding more than 150 information events. Nevertheless, what seems more effective is the Network NGOs’ ability to reach out to vulnerable groups through their own programmes. For example, the Spanish Red Cross has schemes to promote migrants’ employability and FSG has a successful programme focusing on Roma employability (Acceder) (FSG, 2011). Through these activities, these organisations are constantly in touch with vulnerable communities, so they are able to spot discrimination, even when victims have not recognised it (Belsué interview, 18 April 2013; Pulido interview, 20 April 2013; see Appendix). Giménez (Interview, 23 April 2013; see Appendix), from FSG, explains:

‘[identifying discrimination] comes naturally …. When someone is trying to find a job, my colleagues easily realise when the candidate is not invited to an interview for racial reasons; or how it turns out that “the position has been filled” when the candidate is invited [to an interview] and the employer sees his physical appearance. My colleagues often phone the company afterwards and they are told that the position is still available.’

This close contact contributes to reducing underreporting and lumping, and to addressing discrimination promptly. Anecdotal evidence shows that it can even help to eradicate systemic discrimination through positive role models (Giménez interview, 23 April 2013; see Appendix). For example, a Roma woman was rejected for a job at a bakery because the manager believed that ‘Roma don't know how to work’. Yet, she was eventually hired – and even promoted – thanks to FSG mediation (FSG, 2011, p. 35).

Whereas, in Britain, there is higher awareness of the EHRC, the latter does not have a direct interface with complainants, so ‘people don't see the EHRC as a body which can help them, but rather as a body which is there on behalf of the Government’ (Sullivan interview, 29 March 2013; see Appendix).Footnote 95 Instead, the EASS provides the vast amount of discrimination assistance. Yet, awareness of the latter varies greatly by geographical areas: while there is a ‘healthy awareness’ about the EASS services in London and the south-east of England, ‘more work can be done [to improve awareness] in north-east England, Scotland and Wales’ (EASS, 2017).Footnote 96 However, neither the EHRC nor the EASS seems to be actively engaging with vulnerable communities to address this, and it is doubtful that the mere existence of the EHRC and EASS websites will draw the attention of the more marginalised individuals, who may not even have access to smartphones or computers.Footnote 97

Accessibility can also be greatly enhanced by minimising barriers to accessing support services. Both the CERED and the EASS (and, to a limited extent, the EHRC) comply with the basic requirements of providing cost-free, confidential and multilingual assistanceFootnote 98 through a range of channels, including a general-information website, a webform, an e-mail address and a telephone helpline.Footnote 99 However, a key difference between the assistance channels in Britain and those in Spain is that, unlike the EHRC and the EASS, the CERED has managed to offer face-to-face assistance with wide geographical coverage. The SAV has country-wide presence, with eighty-seven access points and at least one branch in each Autonomous Region (SAV, 2012, pp. 2–3, 6–11),Footnote 100 and its advisers often belong to vulnerable communities, which helps to build trust with complainants.Footnote 101

It could be argued that the lack of ‘official’ face-to-face assistance in Britain is not problematic because telephone and online assistance are available (Widdison, Reference Widdison2003). Yet, it is questionable that these can effectively replace face-to-face assistance. Although combining different access channels can increase the potential to reach disadvantaged groups (Griffith and Burton, Reference Griffith and Burton2011, pp. 6–7), substituting face-to-face assistance with remote assistance could have the opposite effect. Concerns have been raised about the use of telephone instead of face-to-face assistance due to the faster pace and lack of visual clues in telephone communications, which may make it more difficult to establish a good interpersonal relationship and decrease the quality of communication (Griffith and Burton, Reference Griffith and Burton2011; Balmer et al., Reference Balmer2012) in a context in which victims tend to value familiarity and trust (Buck and Curran, Reference Buck and Curran2009, p. 25).Footnote 102 Indeed, in the Spanish case, while telephone and website assistance are available, victims overwhelmingly prefer face-to-face assistance (SAV, 2015, p. 50).

Having examined the accessibility dimension, the next bottom-responsiveness dimension to be considered are support services for alleged victims (Table 1, 2.B). In Spain, the CERED ensures, through the SAV, that the support services provided are as comprehensive as possible, including guidance on the possible paths to solve the incident, legal assistance and advice, case-work, negotiation and mediation, and, in some cases, psychological counselling (SAV, 2015, p. 42).Footnote 103 However, given that the CERED does not have legal personality, the Network NGOs cannot undertake strategic litigation on behalf of the CERED.

In contrast, the EHRC can get involved in strategic litigation but does not directly support individuals who feel discriminated against. Instead, the body that is deemed to do so is the EASS. However, the latter only provides legal assistance about ‘how the equality act works, and how it may be relevant to [the complainant's] situation’ (EASS, 2018). This includes helping alleged victims to identify the relevant protected characteristic, the prohibited conduct and the sector in which the incident occurred, as well as assisting them in drafting an action plan to resolve the issue informally – on their own.Footnote 104 Indeed, the EASS tends to ‘steer clear of any sort of view on the merits of whether someone has a discrimination complaint that is valid or not, or what they should do about it, which is the bit that people really need’ (House of Lords, 2016, p. 149). Accordingly, unlike complainants who contact the CERED Network, the EASS users must be referred to another organisation for legal advice, or they must find a lawyer by themselves. In this transfer process, they may lose interest in pursuing their claims further for various reasons, such as a lack of confidence in the legal system or finding the process too cumbersome for what they get in return:

‘When you can only assist victims as regards one part of the process, and, suddenly, they are told that you can only assist them “until here” and that they must be transferred to another service provider to go on with the process, even if you keep in touch with them, in that referral process you lose a lot … you lose many victims.’ (Giménez interview, 23 April 2013; see Appendix)Footnote 105

Another shortcoming of the EASS helpline is that it is run by a generalist companyFootnote 106 and, whilst its advisers are trained, the service is far from equivalent to the former EHRC helpline. For instance, it has been criticised for being ‘manned by inexperienced staff’, keeping a low profile and providing very limited ‘advice and support’ (House of Lords, 2016, p. 149). In fact, since October 2016, the service has controversiallyFootnote 107 been run by the company G4S, which has repeatedly been accused of human rights and discriminatory abuses.Footnote 108

Overall, neither the EHRC nor the CERED provides all recommended assistance levels. The EASS only provides legal assistance and support to informally settle disputes, whereas the EHRC can only represent a few selected complainants in strategic litigation cases. Whilst the CERED's Network provides comprehensive support, legal assistance and advice, it cannot represent claimants in litigation, which limits its responsiveness at the top. In practice, complainants who reach these ‘assistance gaps’ will have to be referred to another cost-free provider, will have to seek legal aid or may have to pay a legal practitioner to pursue their claim. Yet, complainants are likely to drop their actions and ‘lump it’ when they encounter the first assistance gap, which will contribute to higher underreporting rates and lower responsiveness of EBs.

4.3 Top responsiveness: strategic action and co-ordination as the key enhancers of EBs’ role

As discussed in section 2, at the top, EBs’ responsiveness can greatly be enhanced through systemic action and the co-ordination of all antidiscrimination stakeholders. To what extent, then, are the British and Spanish EBs responsive at this level? In both cases, their ‘top responsiveness’ is limited, albeit for different reasons.

Compared to the CERED, which lacks legal personality and enforcement powers, the EHRC has the ‘teeth’ to take systemic enforcement action (Table 1, 3.A).Footnote 109 For instance, it collects information through surveysFootnote 110 and it can conduct inquiries regarding any of its duties, which may lead to a report or a recommendation that can be considered by courts (EqA 2006, s. 16(2)(c), Sch. 2, para. 17). The EHRC can also collect information by conducting formal investigations if it has a ‘reasonable belief’ that someone has committed an ‘unlawful act’ (EqA 2006, s. 20(2)). To exercise these powers, however, the EHRC must comply with extensive procedural requirements (e.g. providing advance notice or publishing the terms of reference),Footnote 111 which limits their practical relevance. Nevertheless, it has other powers that can be of greater interest to achieve systemic changes: it can enter into voluntary agreements with employers ‘in lieu of enforcement’ (EqA 2006, s. 23) and initiate court proceedings on its own name to challenge discrimination if there are no identifiable victims or the affected individuals are not able or willing to do so (EqA 2006, s. 30).Footnote 112 In practice, however, the use of these enforcement powers has notably declined since 2009 and there is increasing agreement among experts that the EHRC is not ‘feared’ by potential defaulting organisations.Footnote 113

Part of the EHRC weakness may be linked to the outsourcing of its helpline in 2012, which has led to not having ‘as good flow through of cases and issues as they [had] previously, because there is one more intermediary [the EASS] and they don't have control over it, as they should do’ (Allen interview, 15 February 2013; see Appendix). Whilst the EHRC has a Memorandum of Understanding with the EASS,Footnote 114 the externalisation of the helpline has led to a ‘sidelining’ between the EHRC and certain vulnerable groups and to the EHRC being less able to respond to new discrimination trends (House of Lords, 2016, pp. 146, 148; Women Equalities’ Committee (WEC), 2018; HM Government, 2018, pp. 23–24). Furthermore, since the EHRC depends on the EASS to identify cases for strategic litigation (Hewitt interview, 29 March 2013; see Appendix), the referral rate has halved since the helpline was externalised (WEC, 2018, Q88, Q91).Footnote 115 The EHRC has made efforts to improve the information flow with the EASS (House of Lords, 2016, p. 148; WEC, 2018), but it is unlikely that any of these will yield the desired results, for several reasons. For instance, as the EASS depends on the GEO, communication is difficult between the EASS and the EHRC, and the latter cannot ask the EASS to perform duties not envisaged in its contract (WEC, 2018, Q88–Q105). Furthermore, the EASS advisers are not lawyers, so they may have more difficulties in identifying strategic cases that could lead to legal developments (WEC, 2018, Q87, Q98–Q99).

Conversely, the CERED Network can identify problems like systemic discrimination thanks to grass-roots assistance based on local NGOs and to networking with other assistance providers.Footnote 116 It is therefore better placed to take strategic action (e.g. issue recommendations). However, unlike the EHRC, the CERED has very limited enforcement powers. It can, inter alia, collect information, publish independent reports at its own initiative or upon request, issue recommendations (including suggestions to amend legislation) and undertake awareness-raising campaigns,Footnote 117 but it lacks legal personality and its own infrastructure. Accordingly, despite having a better connection with social trends, it lacks the independence, resources and powers to actually address the social issues it may identify. In theory, interaction and discussion within the CERED is promoted through its members’ participation in working groups (including the Network NGOs) but, in practice, its institutional activity has been very limited since 2012. Indeed, the ECRI has warned that the CERED's structural and financial dependence from government has ‘seriously compromised [its] sustainability’ and, consequently, ‘[it] has almost ceased to exist’ (ECRI, 2018b, para. 25).Footnote 118

At the top level, EBs can also enhance their responsiveness by taking a co-ordinating role (Table 1, 3.B). EBs can be ‘equality hubs’ that unite antidiscrimination assistance efforts and build on the work of local organisations to address systemic discrimination. This has been the case in Spain thanks to the partnership between the CERED and FSG.Footnote 119 For instance, in the framework of a local plan to boost employment in Mérida, a clothing-store manager contacted by the City Council overtly stated that he ‘didn't want Roma’ as trainees; consequently, the store was excluded from the programme (FSG, 2011, p. 35). In other cases in which Roma have been discriminated against in access to or in employment, FSG has persuaded local employers to change these practices (FSG, 2012, p. 41). In contrast, the EHRC has more difficulties in playing a similar informal networking role at the grass-roots level due to the lack of local branches and its limited contact with local civil-society organisations.Footnote 120 Furthermore, the fact that the Network access points work under the CERED's umbrella has the advantage that complaint data are collected following standardised criteria and published in the CERED's annual reports, which facilitates monitoring. Whilst the EHRC may have some contact with discrimination assistance providers (e.g. Law Centres, Citizens Advice Bureaux, Community Legal Advice Centres), the latter collect data following their own procedures and publish their own reports, which are more difficult to consolidate and compare.

In summary, awareness about the CERED in Spain is lower compared to the EHRC's awareness in Britain, but the former has recently made efforts to increase its ‘bottom responsiveness’ to discrimination through active dissemination of its services and accessible assistance (including face-to-face). Whilst the level of complaints received by the CERED Network is still low, it peaked from 235 complaints in 2010 (SAV, 2015, p. 17) to 853 in 2016 (FSG, 2017). In contrast, the EHRC is not directly accessible by individuals. While the EASS offers assistance through a range of channels and it receives an average of 2,200 calls per month (House of Lords, 2016, p. 52), the potential to increase the EHRC's ‘bottom responsiveness’ seems limited by the lack of both regular contact with vulnerable communities and face-to-face assistance. On the other hand, unlike the EHRC, the CERED's weakness lies in its lack of powers to represent complainants and to undertake strategic litigation, which limit its ‘top responsiveness’ to ‘capitalise’ the information gathered at the bottom. On the whole, both the EHRC and the CERED lack key elements to effectively address systemic discrimination and be responsive at the top. The EHRC has more ‘teeth’ to take action when structural discrimination is identified but it does not use its enforcement powers often enough (WEC, 2019, p. 15) and it lacks strong links with civil society to become an ‘equality hub’ and to identify strategic cases, whereas the CERED has stronger local links but lacks the tools to act in its own name.

5 Learning the lessons and looking ahead: the 2018 Recommendation's potential to encourage more responsive EBs

This paper has argued that EBs matter to respond to discrimination. They are not the panacea, but they are one of the fundamental enforcement tools that can be used to effectively address discrimination.Footnote 121 To do so, however, they must be well designed and resourced, in line with the ‘Responsiveness Framework’ developed in section 2. When this is the case, they can be key players in addressing discrimination, both by proactively promoting equal treatment (‘top responsiveness’) and by supporting vulnerable individuals to react more autonomously to discrimination (‘bottom responsiveness’). In the European context, the RED paved the way for and importantly contributed to the development of a critical mass of European equality ‘watchdogs’.Footnote 122 Yet, its vague standards regarding EBs have allowed MS to fully comply with EU law by setting up, in many cases, largely unresponsive EBs (section 3).

This has been illustrated through the comparison of the British EB, the EHRC and the Spanish EB, the CERED (section 4). This case-study confirms that being independent and having sufficient resources are crucial prerequisites for EBs’ responsiveness. Both the examples of the CERED and the EHRC demonstrate that, if resources are scarce or significantly reduced, EBs’ effectiveness tends to be negatively affected. Yet, resources – on their own – are not sufficient to ensure EBs’ responsiveness. The CERED's extremely low budget does not allow an independent institutional structure and strategic enforcement powers. The EHRC has a higher level of resources but, following the post-Recession budget cuts, its helpline was subcontracted and it lost its direct interface with the public. Still, the EHRC continues to be one of the best-resourced bodies in Europe, but the CERED arguably has a better assistance system at the grass-roots level, despite the latter's acute lack of resources.

The comparison between these two bodies also shows that bottom and top responsiveness are interlinkedFootnote 123 and are necessary for EBs to effectively address discrimination. The CERED's institutional design for assistance provision facilitates bottom responsiveness but its top responsiveness is very limited due to its lack of legal personality and strategic enforcement powers. The EHRC has systemic enforcement powers that better support top-level responsiveness, but its lack of direct contact with the public weakens its bottom responsiveness and limits its ability to build on individual complaints for its top-responsiveness activities.

Cognisant of the problems that this case-study exemplifies, the EU adopted the 2018 Recommendation to supplement the loose provisions of the RED and to encourage the design of more effective national EBs.Footnote 124 A key question is then: Has this Recommendation the potential to trigger changes in EBs institutional architecture that could boost their responsiveness to discrimination? Overall, the Recommendation builds on existing EB literature and most of the international benchmarks considered in section 2,Footnote 125 so the standards proposed largely correspond to the ‘Responsiveness Framework’.Footnote 126 The main virtues of the Recommendation are, therefore, that it aligns EU law with most international best practice and it finally sets out much more clearly what is expected from MS when implementing their duty to set up EBs. This is a significant step forward, but the Recommendation's language is still fairly broad and flexible, particularly for standards on independence, support for victims and accessibility.Footnote 127 For example, the Recommendation only demands that MS ‘should take into consideration the following aspects of providing independent assistance: receiving and handling individual or collective complaints; providing legal advice to victims, including in pursuing their complaints’; it indicates that ‘assistance to victims can include granting equality bodies the possibility to engage or assist in litigation’ and that MS ‘should consider enabling [EBs] to establish local and/or regional offices … or local and/or regional outreach initiatives’.Footnote 128 Thus, MS may comply with the Recommendation even if the national EB does not provide legal advice and does not have any regional or local presence. Considering the Recommendations’ uncompelling language and its soft-law nature, the EU will probably need to proactively encourage its implementation and even consider binding measures to stimulate MS to introduce meaningful changes.Footnote 129

In a context in which the BlackLivesMatter movement has brought systemic racism to the attention of the public worldwide and the COVID-19 pandemic is hitting ethnic minorities hard (Devakumar et al., Reference Devakumar2020), EBs can matter more than ever as part of wider public efforts to address racial and ethnic-origin discrimination if they are designed responsively. The Recommendation has some potential to be a stepping stone to trigger positive changes in national EBs architecture, but it is doubtful that MS will take it seriously enough to make a difference in practice.

Conflicts of Interest

None

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Mark Bell, David Gurnham, Harry Annison, Matthew Nicholson and the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this article. The usual disclaimers apply.

Appendix: Interviews’ overview