INTRODUCTION

Emergency medicine (EM) education in Canada is changing and evolving rapidly. Simulation,Reference Langhan 1 point-of-care ultrasound,Reference Woo, Frank and Lee 2 Free Open Access Medical (FOAM) Education,Reference Cadogan, Thoma and Chan 3 competency-based medical education,Reference Iobst, Sherbino, Cate and Ten 4 and drive to produce sound education scholarshipReference Sherbino 5 exemplify a paradigm shift in both the content and delivery of medical education. As the complexity of medical training increases, emergency physicians (EPs) who take on education leadership roles require expertise in curriculum development, instructional methods, assessment, faculty development, scholarship, and more. Accordingly, the manner in which education leaders are identified, trained, and supported needs to be clearly defined.

The clinician educator (CE) is defined as a clinician who is active in a health professional practice and applies theory to education practice, engages in education scholarship, and serves as a consultant to other professionals on education issues.Reference Sherbino, Frank and Ed 6 EPs in education leadership roles might not fulfill all aspects of this definition, due in part to a lack of formal training for CEs (in contrast to well-defined training pipelines for clinician scientists). In 2013, the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians (CAEP) Academic Symposium made recommendations for defining education scholarshipReference Sherbino, van Melle and Bandiera 7 and developing and supporting scholars,Reference Bandiera, Leblanc and Regehr 8 along with a “how to” guide for education scholarship.Reference Bhanji, Cheng and Frank 9 The goal of the 2016 consensus process is to help EM residents and early career EPs with an interest in education understand the options for training and support requisite for developing expertise in education.

Formation of an expert panel

An expert panel of Canadian EM education leaders was assembled with attention to the following factors: geographic representation, language, scope of practice, training route, previous and present education leadership roles, and advanced training in medical education. The final panel composition included 11 EPs representing 9 Canadian medical schools from both French and English speaking schools. The panel included EPs with certification from the College of Family Physicians of Canada through the Special Competence in Emergency Medicine (CCFP-EM), training through the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (FRCPC), and training in pediatric EM through the Royal College (FRCPC-PEM). The panel represented a variety of education leadership positions and a mix of advanced training in medical education. The panel met monthly over the course of a year via teleconference to discuss and develop the recommendations.

Scoping review

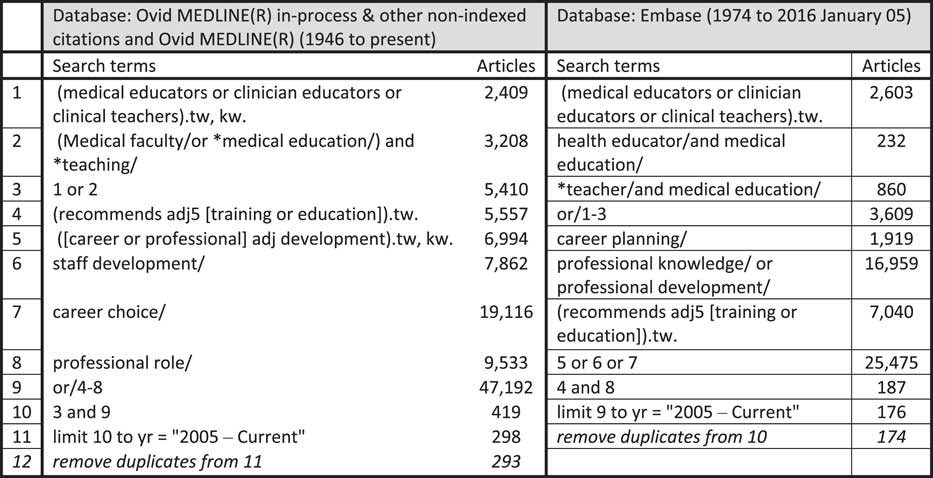

Our panel was more interested in breadth over depth and, as such, chose to use a scoping review for our literature search. Scoping reviews do not formally appraise the quality of or synthesize results of research papers and can generate a very large number of studies to search through. It did, however, allow us to rapidly identify key concepts and use papers with multiple study designs.Reference Arksey and O’Malley 10 With the help of a hospital librarian, the panel searched PubMed and Embase using the following search terms: medical educator, clinician educator, clinician teacher, career professional development, career choice, and professional role. The search was limited to articles from January 1, 2005 to December 7, 2015. Abstracts were reviewed independently by two panelists (RW and JA) to determine inclusion, and disagreements were resolved by consensus. Articles were distributed amongst the panel for critical appraisal using the following pre-determined categories: CE scope of practice, assessment of CEs, assessment of training programs, attracting CEs, faculty development, barriers and facilitators for CEs, and academic promotion. Thematic analysis of the included article summaries was performed by two authors (JA and RW).

Survey

The panel members divided the 17 Canadian medical schools and used referral sampling to identify individuals at each institution who currently or previously fulfilled the definition of a CE. By consensus, the panel came to a practical definition in order to enlist our sample of CEs. This was defined as: an emergency physician who holds or has held a formal education position in the last 10 years and makes/made decisions about curriculum.

The panel identified 262 education leaders from 16 of the 17 medical schools (the panel was unable to identify a contact person at the Université de Sherbrooke). By way of a structured written survey, educators were asked to identify the most important competenciesReference Sherbino, Frank and Ed 6 required for success in education leadership, whether they had acquired advanced training in medical education prior to assuming or during their position, and whether they would recommend advanced training to others prior to taking on that role.

Results of the scoping review

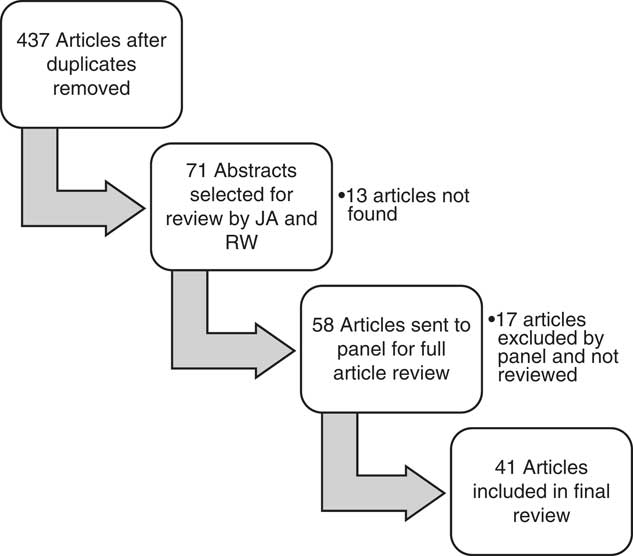

The search strategy is shown in Figure 1. After duplicates were removed, 437 articles remained. JA and RW reviewed the abstracts and agreed by consensus on 41 articles for a complete review (Figure 2). Several themes were identified from the systematic review of the literature: the importance of the CE role for the ongoing advancement of medical education, strategies for being a successful CE, descriptions of training programs, and the challenges associated with academic promotion for CEs.

Figure 1 Search strategy for the literature review.

Figure 2 Review of articles from the scoping review.

Medical educators form a critical role to the advancement of a medical institution.Reference Sherbino, Frank and Ed 6 , Reference Castiglioni, Aagaard and Spencer 11 This goes beyond expanding and refining the repertoire of medical school teaching.Reference Searle, Hatem and Perkowski 12 It also includes supporting the academic mission of the institution and adapting to the changing environment of educational standards and accreditation. A CE becomes a consultant to her or his colleagues and to the institution in which they work, helping them achieve the previous goals. Strategies for success as a CE have been identified: clarify what success means for you; seek mentorship; develop a niche and engage in relevant professional development; network; transform educational activities into scholarship; and seek funding and other resources.Reference Castiglioni, Aagaard and Spencer 11

Experiential learning is no longer sufficient for becoming a CE.Reference Sullivan 13 Training programs for medical education have exploded over the last two decades. There is a large number of master’s programs,Reference Tekian and Harris 14 fellowships,Reference Thompson, Searle and Gruppen 15 and academies,Reference Searle, Thompson and Friedland 16 , Reference Lamantia, Kuhn and Searle 17 Fellowships have been developed across specialties at individual medical schools,Reference Steinert and Mcleod 18 and there are specific fellowships for EM educationReference Lin, Santen and Yarris 19 – Reference Yarris and Coates 21 and efforts to ensure the quality of these various training programs.Reference Al-subait and Elzubeir 22 , Reference Gruppen, Simpson and Searle 23

CEs have historically faced challenges in academic promotion for a variety of reasons.Reference Alexandraki and Mooradian 24 Whereas some institutions have had success in accepting novel forms of scholarship, others still base promotion primarily on grants and peer-reviewed publications;Reference Van Melle, Lockyer and Curran 25 whereas some CEs obtain/receive grants and publish, many produce other forms of scholarship.Reference Sherbino, van Melle and Bandiera 7

Results from the survey of education leaders

Of the identified 265 education leaders, 142 completed the survey for a response rate of 53.6%. The survey was distributed electronically with a pre-notification message and three email reminders sent over 3 weeks in February 2016. The survey was created in FluidSurveys (Ottawa, ON), and the data were analysed using Excel. There was a broad range of certification and years of experience amongst the respondents (Table 1). Most of the respondents have spent the majority of their professional time in the clinical domain (Table 2). The majority of respondents recommended advanced training prior to taking on an educational leadership role (Table 3).

Table 1 Demographics of respondents (n=142)

a Other certifications listed include FRCPC (pediatrics), CSPQ, ABP, ABEM.

Table 2 Percentage time devoted to professional roles (n=142)

Table 3 Competencies important for success stratified by advanced medical education training

Greater than 50% of respondents felt that all of the competencies of a CEReference Sherbino, Frank and Ed 6 were important or very important (see Table 3). The degree of agreement varied by competency and by the education leadership role (Table 4). The competencies that were consistently identified by all roles were leadership, communication skills, assessment, and curriculum development.

Table 4 Competencies “very important” or “important” for success by role, as identified by all

Presentation of results and draft recommendations at the Academic Symposium

The recommendations that were drafted by the panel were presented to 100 EPs at the 2016 CAEP Academic Symposium on June 4, 2016. Through a live survey poll and facilitated discussion, audience members provided feedback to the expert panel. The main themes identified were to categorize the recommendations at the individual, the academic departments and divisions (AD&D), and CAEP Academic Section levels. The audience discouraged having recommendations at the specific CE competency level for each type of leadership role, because the competencies were too granular and were subject to institutional and role variability.

Recommendations

Recommendations for emergency physicians and residents (our future clinician educators):

1) Advanced training in medical education is recommended for any EP or resident who plans to take on an education leadership role.

2) Advanced training should take the form of at least one of the following: targeted courses/workshops, formal certifications, a fellowship, or a master’s degree; the skills acquired should be applicable to the role that he or she plans to pursue.

3) EPs or residents who consider becoming CEs should seek out mentorship to consider all career pathways and training opportunities.

Recommendations for academic departments and divisions:

1) AD&D should work with their institutional strategic plans to regularly perform a needs assessment of their future CE needs. This will allow them to identify and encourage potential individuals who would fulfill education leadership roles.

2) AD&D should provide advanced training and mentorship opportunities, protected time or preferential scheduling, and financial support to complete advanced training.

3) AD&D should advocate for the recognition of education scholarship in their institution’s promotions process.

Recommendations for the CAEP Academic Section:

1) To advance EM, the CAEP Academic Section should support the mentorship and networking of CEs across Canada.

Discussion of recommendations

The panel sees a tremendous change on the horizon for EM education. To be prepared for the future, our CEs need to have the full set of skills and knowledge required to become education consultants.Reference Sherbino, Frank and Ed 6 This also resonated from the results of our education leaders survey. This set of skills is too complex to learn on the job, and specific training will be necessary. This will put our clinicians in a position to achieve all of the competencies of a CE. This will require action from individuals, AD&D, and the CAEP Academic Section.

EPs and residents should receive formal training in medical education prior to taking on a leadership role. This recommendation came from the majority of respondents of our survey. The endorsement was greater for those with previous medical education training and may represent some degree of cognitive dissonance bias in both groups. Those who have previous training may be more likely to think it was valuable because they invested their time and money. Those without previous training may be less likely to think it was valuable because they would potentially be admitting that they were not as prepared as they should have been for the role they took on. Keeping this bias in mind, 58% of those without advanced training still felt it should be required.

There is a myriad of training opportunities available for medical education. Within training options, there are multiple formats. A master’s program can be face to face, distance learning, or a hybrid model.Reference Tekian and Harris 14 Not all institutions will have local access to training, so travel may be required. Because of these factors, it will be difficult for prospective CEs to know what the best training is for them. The literature searchReference Castiglioni, Aagaard and Spencer 11 and our survey both strongly support the need for mentorship from senior CEs to guide them through this process. Additionally, individuals should discuss their interests with their department heads who can advise them on future career opportunities.

Training CEs will require strong leadership from AD&D. AD&D needs to work with their institutional strategic plans to identify their educational goals. From here, they will be able to determine where their CE needs are. CE positions need to be planned for in advance, and potential candidates should be identified. As soon as candidates are identified, they should be connected with potential mentors who can guide them through their training. This will allow candidates to tailor their advanced training towards the role that they plan to take on.

AD&D also needs to advocate for training opportunities at their own institution to make them more accessible. Additionally, future CEs need to be supported. Getting advanced training in medical education is expensive and time-consuming. From our survey, individuals who completed advanced training received very little support to complete advanced training, and those who did not complete training cited lack of support as a barrier. This would ideally involve protected time and/or financial support but, at a minimum, requires preferential scheduling to complete the advanced training. These measures will ensure that taking on advanced training is feasible for many. As a speciality, we will need a constant supply of CEs, because the number of CE positions in EM are vast and expanding.

AD&D also needs to advocate for academic promotions criteria that recognize education scholarship. This was identified in the literature as a significant barrier for many CEs.Reference Alexandraki and Mooradian 24 , Reference Van Melle, Lockyer and Curran 25 The traditional clinician scientist pathway does not always fit the career trajectory of a CE. Additional forms of scholarship need to be represented in the portfolio of a CE. This will ensure that CEs feel their scholarly contributions are valued.

The CAEP Academic Section can play a networking role towards this goal. The Education Scholarship Committee is a community of practice for Canadian EM educators with representatives across Canada. This working group can serve as a contact point for future CEs looking for mentorship towards their career goals.

In summary, these recommendations serve as a framework for training and supporting the next generation of Canadian EM medical educators.

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge Alexandra (Sascha) Davis at the Ottawa Civic Library and Angela Marcantonio at the University of Ottawa EM Research Group for their help with the literature search. The authors also thank Kelly Wyatt from the CAEP office for her assistance with panel meetings, information management, and the coordination of the symposium.

Competing interests: None declared.