Over the past two decades, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has developed guidelines for broad mental health categories1 and quality standards.2 However, systematic implementation of these has not occurred despite general agreement and a national direction that this should happen. Clinicians have developed and evaluated pathwaysReference Rathod, Garner and Griffiths3 based on broad categories for use by clinicians in Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, which are available to patients and other service users. These developments have received strong support from clinicians, managers, patients, carers and local commissioners. A key factor to aid implementation has been the recognition that the primary pathway being followed by each patient needs to be identified. Second, clinical- and patient-rated outcome measures need to be implemented and, third, each patient needs to be assessed against the standards set by NICE and the Pathways groups and Trust Medicines Management Procedures. It was also recognised that this would provide essential information to develop a clinically meaningful costing system. Clinical and needs profiles could be developed from the pathway allocation and the clinical measure used (Health of the Nation Outcome Scales; HoNOS) to form groups for costing, e.g. as clusters, and for accounting for comorbidity using weighting factors such as comorbid symptoms, risk ratings, physical health scoring or social measures from DIALOG.

Development of payment systems

Over the past decade, attempts have been made to move away from block contracts to fund services, but this has yet to be successful in mental health. The route pursued so far has been to use a ‘clustering’ process to derive groups of patients using a mental health clustering tool4 and then to attach costs to these clusters. However, although most patients are allocated to a cluster by mental health practitioners in National Health Service (NHS) trusts, the reliability of allocation to these clusters and their validity has yet to be demonstrated.5 They have not been widely adopted for contracts or costing services. Nevertheless the Five Year Forward View for Mental Health Reference Kingdon6 specified that a move to outcome- and quality-based payments and replacement of block contracts should occur by 2017/18 for adult mental health services.7 A framework approach is advocated that:

• tailors quality and outcomes measures to local needs;

• is relevant to individuals and clinicians;

• matches the needs of the service in terms of timeliness and benchmarking;

• is used as an improvement tool.

Some areas have taken forward systems that incorporate outcomes, e.g. Oxford, but the major difficulty is that these outcomes are difficult to interpret without comparative data or are broad and involve multiple agencies, e.g. improving physical health outcomes. Associating costs with these outcomes can lead to pursuit of perverse incentives, e.g. influencing data scoring (‘gaming’) rather than reflecting clinical care. Funding changes then can destabilise providers or commissioner budgets.

Essentially, the key questions that need to be addressed to produce a reliable costing system that promotes quality of care are:

• How should patients be grouped?

• What outcomes should be used and how should they be simply described?

• What costs should be included and how should they be allocated?

Use of clinical pathways and outcomes

Unfortunately, ICD-10 diagnostic coding of community patients is poor in most trusts; however, allocation to broad NICE categories would be simpler and practical to implement.

There is now an abundance of outcome measures used in research studies that have demonstrable validity and reliability for broad categories. There are also patient-rated outcome measures that have been validated in severe mental illness, e.g. DIALOG.Reference Priebe, McCabe, Bullenkamp, Hansson, Lauber and Martinez-Leal8 Finally, costs can be determined and allocated using the electronic systems that are now available, and these systems are becoming increasingly detailed and patient based. They can be used for individual direct costs but also for estimates of indirect costs, e.g. supporting management and estate expenses.

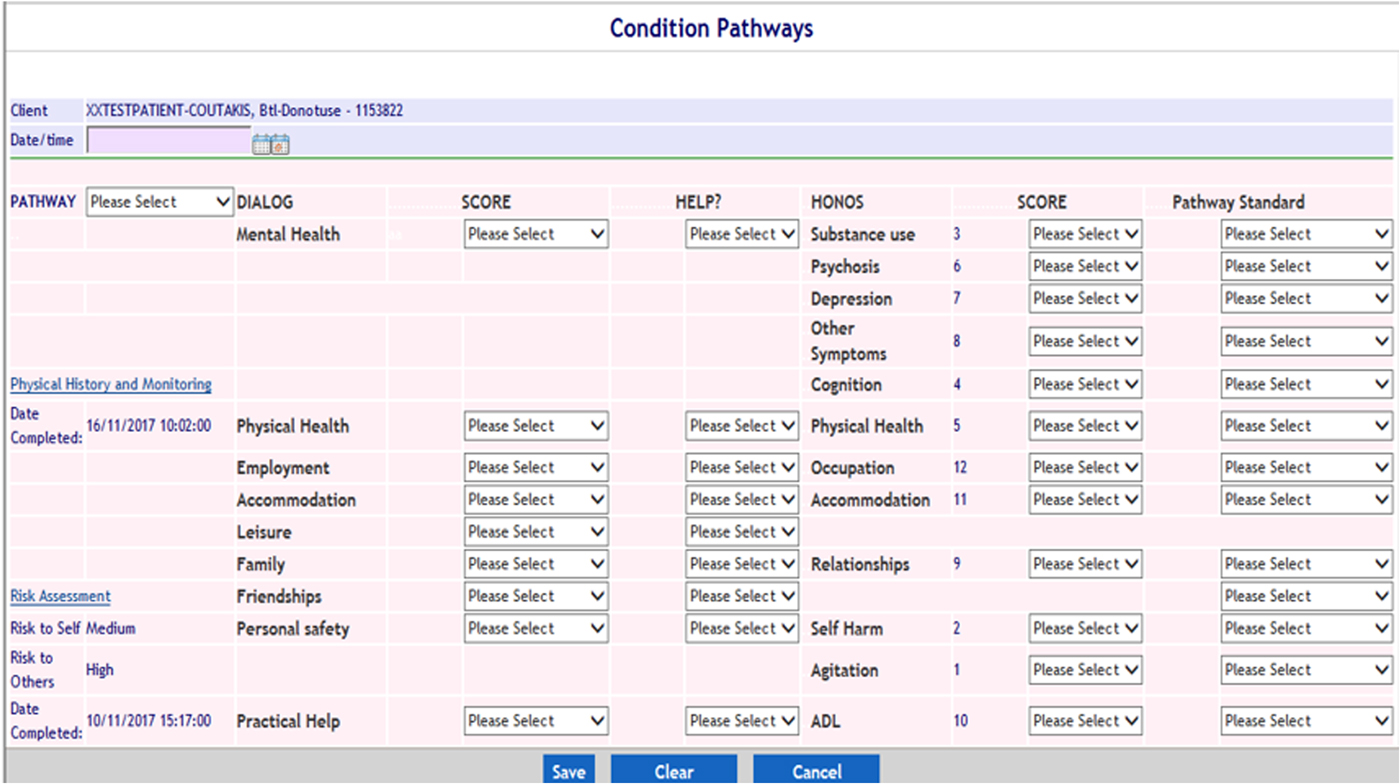

The decision was taken to adapt the trust electronic record, Rio (Fig. 1), to enable a process of individual allocation to a pathway, outcome measurement and standard assessment to be systematically implemented, replacing the previous system for clustering. The pathways originated from application of the NICE clinical guidelines to mental health services and cover broader and more common conditions (psychosis and affective, borderline personality, eating and organic disorders). Intellectual disability was not included as it is not a primary reason for referral to mental health services, although it can present as a comorbidity.

Fig. 1 Electronic patient record data entry form for allocation of pathway, outcome measurement and standard assessment.

Method

Patients in adult and older people's services across the trust (which covers a population of 1.3 million) were allocated to six broad pathways using the electronic recording system (Rio). These were psychosis, borderline personality, affective, eating and organic disorders, and an ‘other’ category. Where comorbidities existed, staff were asked to allocate patients to the pathway which was primarily being followed. Where doubt existed, the advice given was that the multidisciplinary team should make the decision. Clinicians were already familiar with the use of HoNOS across these groups; these were used as the clinician measure and DIALOG was the patient-rated outcome measure. The latter has been widely used in severe mental illness, addresses key areas of need for care planning, and links very well to the scales rated by HoNOS and standards set by NICE. The expectation for the future as outcome measurement becomes embedded, and as resources and technology allow, is that more specific measures will be used, e.g. Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression (PHQ9) and Generalised Anxiety Disorder (GAD7) for affective disorders or Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (CORE) for borderline personality disorder.

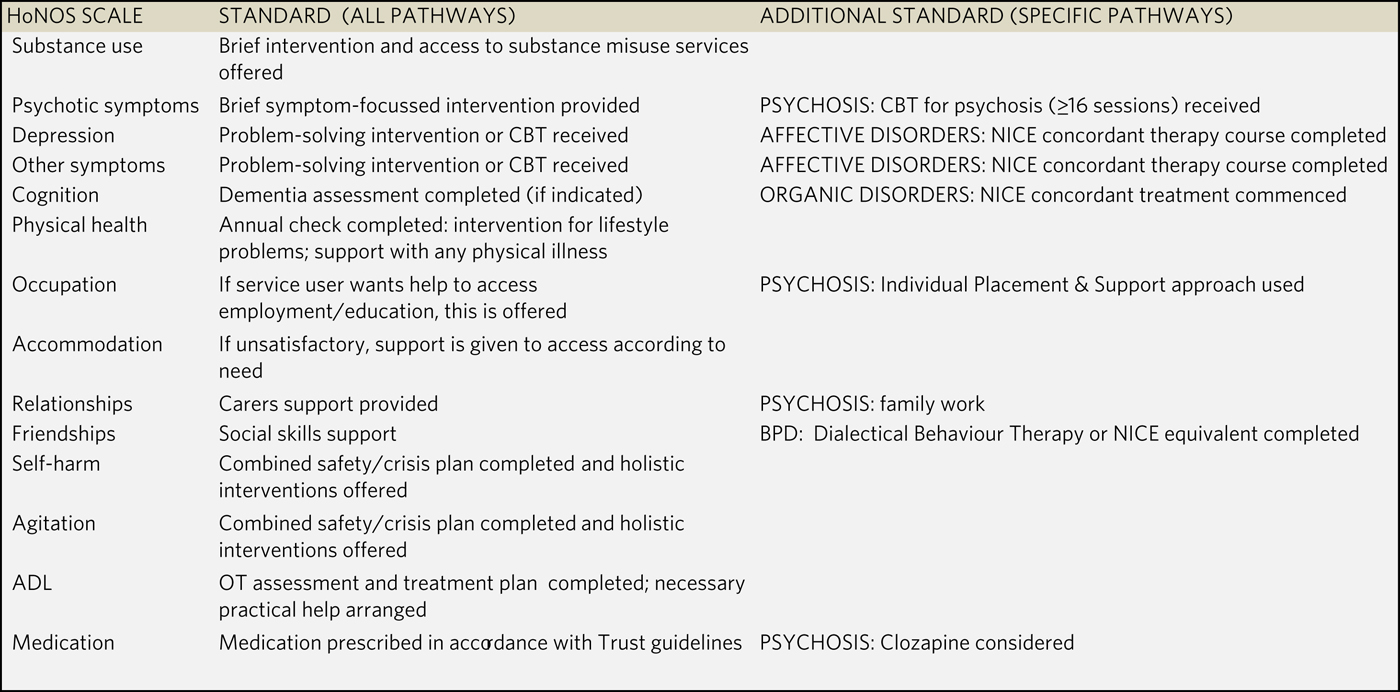

Collection of information on interventions was considered, but the decision was made that whether standards were met was more important. Standards related to the current situation and could cover a number of interventions, e.g. approved psychological treatments or physical health interventions. Each of the HoNOS and DIALOG areas, therefore, were assessed against relevant standards (Fig. 2) to determine whether the standard was:

• already met

• in progress

• not applicable

• on waiting list

• resource not available

• brief intervention

• patient declines

• other response

Fig. 2 Standards set.

HoNOS, Health of the Nation Outcome Scales; CBT, cognitive-behaviour therapy; BPD, borderline personality disorder; ADL, aids to daily living; OT, occupational therapist.

An algorithm was developed from the NHS England guide to clustering (using the ‘Red’ rules, which specify scores on HoNOS that are essential to eligibility for individual clusters) to meet NHS Improvement (NHSI) requirements for clusters to be allocated. This was automated to improve reliability and reduce clinician workload, as the latter was recognised to be increased, at least in the short term, by these developments.

Results

The system went live and replaced the previous requirement for clustering on 11 April 2018. There were some minor coding issues with the algorithm initially. The Rio form for entering data needed minor adjustments, e.g. to include a review date for the form. The trust's data warehouse presentation system ‘Tableau’ also required development to track whether Rio forms had been completed and provide displays of the input data. All these issues were rectified.

Clinicians fed back that DIALOG was difficult to use with patients with dementia, and so alternative patient- or carer-rated outcome measures such as DEMQOL are being considered.

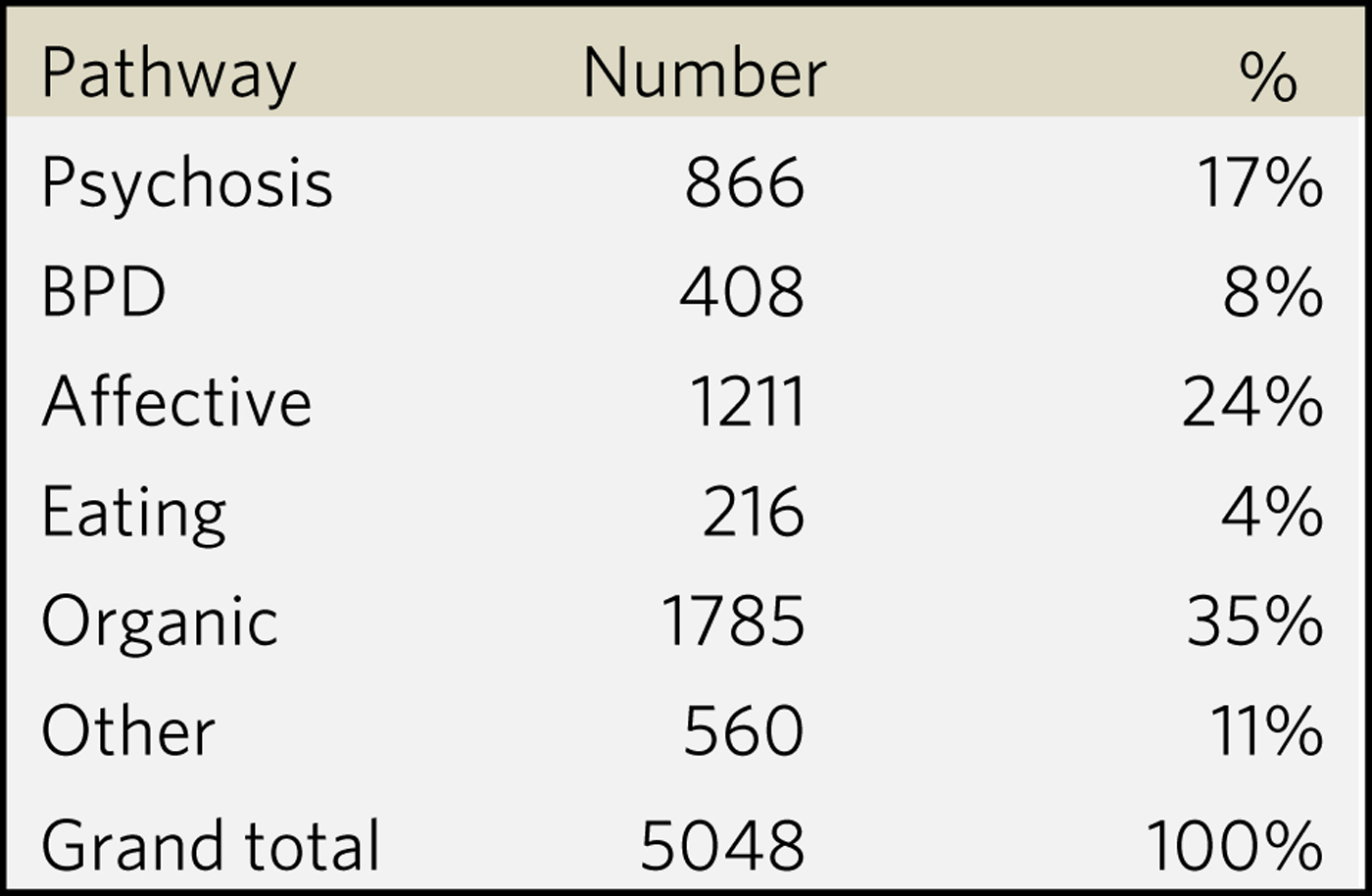

A total of 5048 patients were rated and allocated to a pathway in the first 3 months (Fig. 3). Over 90% of HONOS items were completed: 70% of patients were assessed against relevant standards and 50% of patients (excluding organic pathway) had DIALOG completed.

Fig. 3 Allocation to pathways.

BPD, borderline personality disorder.

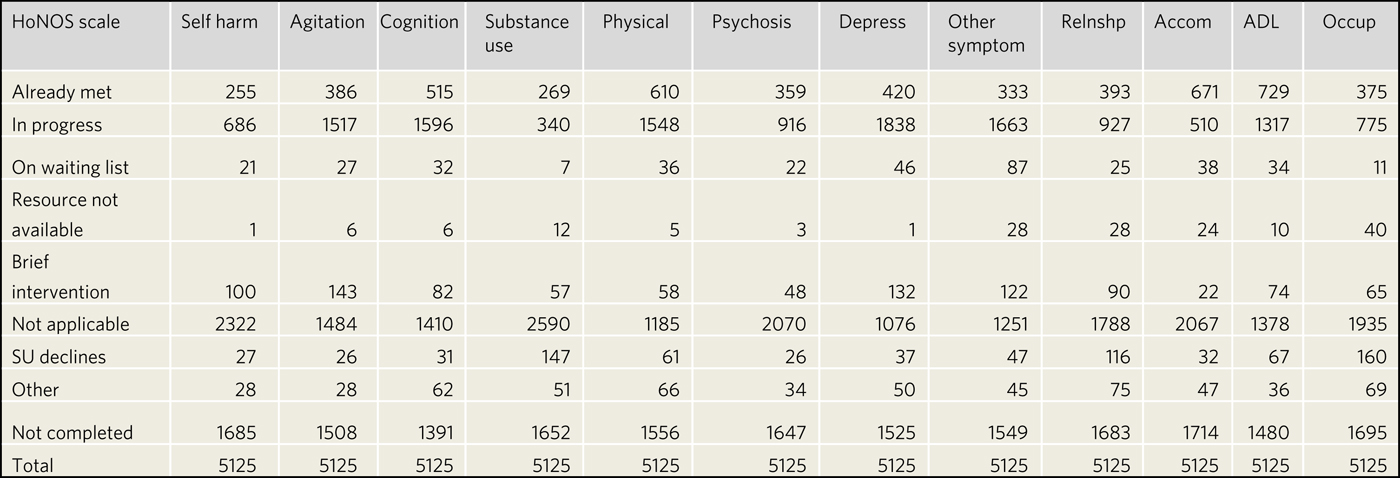

A great deal of data has been produced describing patient clinical characteristics and needs within the pathways. There is also a substantial amount of information on whether standards are being or in progress to be met, etc. (Fig. 4). These data are now updated daily on ‘Tableau’, to which all staff have access, for breakdown into area, teams and individual caseloads. Improved ways of meaningfully using the information and presenting it to teams are being explored.

Fig. 4 Assessment against standards.

HoNOS, Health of the Nation Outcome Scales; depress, depression; relnshp, relationships; accom, accommodation; ADL, aids to daily living; occup, occupation; SU, service user.

The clustering process has progressed; since the algorithm was introduced, there have been some differences in the clusters produced (increase in non-psychotic mild to moderate and decrease in less severe psychosis).

Discussion

The project has demonstrated that it is possible to obtain clinically relevant data using the electronic patient record completed by community and in-patient mental health staff. The response of staff has been positive especially regarding the use of DIALOG linked to care planning and the automatic derivation of the clusters. The groups leading the development of pathways in the trust and the local commissioners have also strongly supported the effect that the process is having on implementation. Completion of records has been well beyond the expected level, suggesting that the system is considered to be clinically relevant. It is still very early days and only limited training and guidance were provided, but ‘Help’ screens, e-learning and drop-in teleconferences were made available to all staff. There remain some issues to resolve, e.g. how to reliably rate against standards: ‘absence of resource’ and patients ‘on waiting list’ were rated very low, yet these are broadly recognised to be an issue across the trust and nationally. ‘In progress’ was also remarkably popular.

It will now be possible to attach costs to the broader clinical groups, which is a first step away from the block contract. Initially, this may simply occur by subdivision of the current budget between the groups. There are also outcome and standards data for each group to track improvement in these areas, e.g. DIALOG is particularly important in this respect as it is independently rated by the patient, who specifies if they want help in individual areas: meeting those needs would self-evidently be a positive outcome. This can form the basis for negotiation, e.g. if standards and subsequently outcomes in a specific pathway such as psychosis are to be improved, what new resources are required and how much improvement in practice is needed to achieve this? Conversely, if budgets are to be reduced, how much should be taken from each patient group and which standards are likely to be sacrificed? This can be further assessed by the effects on outcome measures.

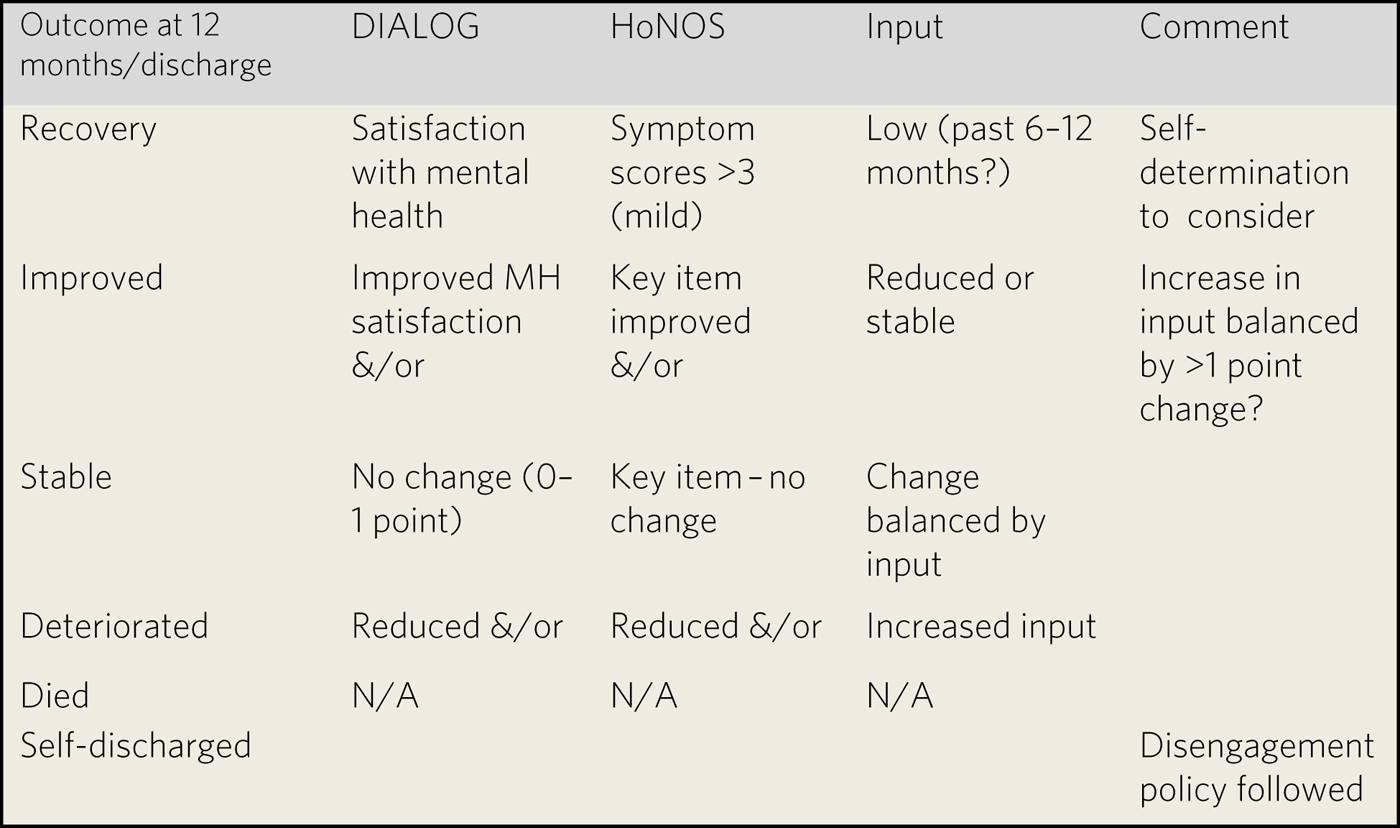

It is still important to develop a way of understanding how to use and aggregate outcome data. A possible route is to emulate and adapt the system used by the Improving Access to Psychological Treatment programme in developing broad aggregate measurements of recovery, meaningful improvement, stability and deterioration.Reference Clark9 This could be done by using the DIALOG needs data: for instance, recovery could include patients who are ‘satisfied with their mental health’ as assessed by the scale, but this would also need to be triangulated with the clinical rating measure and service input (Fig. 5). If HoNOS rated an individual as still quite unwell or the individual was requiring or recently required substantial service input, e.g. hospital admission, they might still be rated ‘improved’ but perhaps not recovered.

Fig. 5 Possible use of routine data to define outcome groups.

HoNOS, Health of the Nation Outcome Scales; N/A, not applicable.

Implications

Current systems to collect data for ‘clustering’ could be modified and extended for mental health staff to allocate patients to clinical pathways, measure clinician- and patient-rated outcomes, and assess against quality standards. These data could then be used to initiate patient-based low-risk costing of services, e.g. by subdividing budgets according to clinical pathway and use outcome, and using standard data to characterise and compare groups at the trust, area, team and even, with caution, individual levels. Subdividing current contract values into broad pathways will be relatively straightforward, though approximate, and less risky for commissioners and trusts while a more sophisticated costing methodology is being developed.Reference El Alaoui and Lindefors10 It will ensure that there is a patient-focused approach for investment and disinvestment and will also drive improvements in costing processes as well as clinical pathways, outcomes and standards assessment. It has the potential to link patient groups and costs in a clinically meaningful way to improve implementation of evidence-based practice, quality of care and outcomes. Southern Health NHS Trust and commissioners are now working together to implement the findings from this work in allocating resources. It has been presented to the NHSI Currency ‘Task & Finish’ Group and its implications are currently being considered.

About the author

David Kingdon is Emeritus Professor of Mental Health Care Delivery at the University of Southampton and was formerly Clinical Director for Adult Mental Health Services at Southern Health Foundation Trust.

Acknowledgements

I thank the Southern Health Foundation Trust (SHFT) Pathways and Costing groups, Sue Barrett and Sarah Langton, the SHFT IT Department, and Letsie Tilley and Stefan Priebe for allowing the use of DIALOG.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.