Clozapine has been considered the gold standard for treatment-resistant psychotic disorders since the 1980s.Reference Siskind, McCartney, Goldschlager and Kisely1 It demonstrates a 50–75% response rate among those who fail to achieve remission with conventional first- or second-generation antipsychotics.Reference Agid, Arenovich, Sajeev, Zipursky, Kapur and Foussias2 Clozapine is associated with better long-term outcomes than other antipsychotics or no treatment, including lower long-term all-cause mortality rates,Reference Vermeulen, van Rooijen, van de Kerkhof, Sutterland, Correll and de Haan3 reduced violent offendingReference Bhavsar, Kosidou, Widman, Orsini, Hodsoll and Dalman4 and readmission rates.Reference Land, Siskind, McArdle, Kisely, Winckel and Hollingworth5 Despite superior efficacy, clozapine remains significantly underutilised and its initiation is often substantially delayed. The Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness study reported that only 14–50% of eligible patients were treated with clozapine.Reference Stroup, Lieberman, McEvoy, Davis, Swartz and Keefe6 Furthermore, data from the UK shows that clozapine initiation is typically delayed by approximately 4 years.Reference Howes, Vergunst, Gee, McGuire, Kapur and Taylor7

One common problem occurs when treatment-resistant patients are not able to accept clozapine or associated blood tests because of symptoms of acute psychosis, including impaired insight and delusional beliefs. Although the Mental Health Act 2008 (MHA) in England and Wales gives the legal authority to administer involuntary drug treatment and ancillary investigations, including blood tests to support clozapine use, most patients who require but are non-adherent to antipsychotics are prescribed long-acting injections because of the practical difficulties of enforcing oral treatment. However, since clozapine is not available as a long-acting injection, an unwillingness to take the oral form of clozapine has hitherto precluded clozapine treatment. Although compulsory administration of medication is not uncommon in psychiatric care, this is rarely used with clozapine treatment, with only a few facilities worldwide reporting the use of nasogastricReference Till, Selwood and Silva8 and intramuscular clozapine.Reference Henry, Massey, Morgan, Deeks, Macfarlane and Holmes9–Reference Lokshin, Lerner, Miodownik, Dobrusin and Belmaker13 In this study, we present our 3-year experience with short-acting intramuscular clozapine in the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM).

Method

Study design

Observational data from SLaM were collected to follow-up a cohort of patients prescribed intramuscular clozapine as a short-term strategy to initiate oral clozapine. Our aim was to evaluate its potential value in initiating and maintaining clozapine in patients initially reluctant to take oral clozapine. Transition from intramuscular prescription to oral clozapine was the primary outcome. The secondary outcome was all-cause clozapine discontinuation, a widely used outcome measure in observational studies. Post-discharge discontinuation rates were investigated to assess long-term adherence to oral medication outside a hospital setting, where concordance cannot be prompted and supervised by healthcare professionals. Finally, we compared all-cause clozapine discontinuation rates with those of a comparison group of patients started and maintained on oral clozapine, without intramuscular prescription, while detained under the MHA 2008 in SLaM. This analysis was conducted to investigate whether addressing an initial reluctance to accept clozapine treatment by prescribing the intramuscular formulation will lead to long-term adherence at rates similar to or different from patients who accepted oral clozapine from initiation.

Intramuscular clozapine

The intramuscular clozapine used in this study is manufactured by Apotheek A15 (formerly Brocacef) in the Netherlands and was approved by the Drugs and Therapeutics Committee of SLaM in 2016. Because of the need for daily administration and the large volume that must be injected to achieve maintenance doses of clozapine, intramuscular clozapine is not suitable as a long-term treatment. Although there is no upper limit, the protocol suggests not exceeding 14 days of injections; nonetheless, previous data report safe use of intramuscular clozapine for up to 96 days.Reference Henry, Massey, Morgan, Deeks, Macfarlane and Holmes9 Therefore, the SLaM protocol (see Supplementary file 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.115) allows for intramuscular clozapine as a short-term intervention to initiate or re-initiate clozapine treatment in patients who refuse oral medication, with a view to converting to oral clozapine once adherence is achieved. The decision to prescribe intramuscular clozapine is undertaken on an individual basis and our local protocol states that it must be agreed by a multidisciplinary team, the Director of Pharmacy and a second-opinion doctor appointed by the Care Quality Commission under the provisions of the MHA 1983. The final decision is driven by a comprehensive assessment, which includes extensive information gathered from various sources such as family discussions, capacity assessments and best-interest meetings. The latter aims to reach a decision in the best interest of a patient who is assessed as lacking capacity for the decision in question.

Once intramuscular clozapine is prescribed, the choice of oral clozapine must be offered at every administration, and the injection is only administered as a last resort when oral clozapine is refused. The strength of intramuscular clozapine is 25 mg/ml and each ampoule contains 5 ml (125 mg). Current recommendations, based on clozapine pharmacokinetics, assume oral bioavailability of clozapine to be approximately 50% of the intramuscular formulation.Reference Meyer and Stahl14 As the injection of larger volumes can be painful, it is suggested that the maximum volume that can be injected into each site is 4 ml (100 mg), which gives approximately the equivalent bioavailability as 200 mg oral clozapine. For doses greater than 100 mg daily, the dose may be divided and administered into two sites based on individual preference. To minimise the number of injections, once daily dosing is preferred.

Intramuscular clozapine cohort

All individuals prescribed intramuscular clozapine between 1 June 2016 and 7 March 2019 in an in-patient care setting within SLaM were included in the study. All patients lacked capacity to consent to treatment. Each patient prescribed intramuscular clozapine was added to a register and linked to electronic medical notes and pharmacy dispensing records. Patients were followed up on with regard to concordance to oral clozapine treatment until clozapine discontinuation or 2 years after intramuscular clozapine prescription or 31 July 2019, when the data collection ended, whichever occurred sooner. Time to all-cause post-discharge discontinuation was defined as the time from the date of discharge until the date oral clozapine was stopped, 1 year of treatment or end of data collection (31 July 2019), whichever occurred sooner. Treatment discontinuation was defined as a discontinuation for longer than 7 consecutive days, even if clozapine was later re-initiated.

Patient demographics and clinical data, such as the duration of illness, prior use of clozapine and the date of clozapine initiation, discharge and transition from intramuscular to oral clozapine, were collected from electronic medical records. Global clinical severity was rated retrospectively at intramuscular clozapine prescription, using the Clinical Global Impression Improvement Scale (CGI-I), by manual analysis of patients notes in the electronic medical records by an experienced psychiatrist (C.C.). Further data included clozapine injection date(s) and dose(s), and use of restraints. Reasons for clozapine discontinuation where applicable were obtained from descriptive medical records. Patients who were discharged from SLaM were followed up on through their registered pharmacies responsible for clozapine supply. A questionnaire was sent to respective pharmacists asking whether the patient under their care remained on clozapine treatment and, if not, the date and reason for discontinuation.

Comparison group: historical cohort

The comparison group included patients with a diagnosis of a treatment-resistant psychotic disorder (ICD-10 codes F20–F2915) aged between 18 and 65 years, who were initiated on oral clozapine in a SLaM facility in routine clinical practice between 1 January 2007 and 31 December 2011. We selected patients who were initiated on clozapine while detained under the MHA 2008 (Section 2, Section 3 or Section 47/49) to represent compulsory treatment in the historical cohort. These data were collected as part of a previous study investigating reasons for clozapine discontinuationReference Legge, Hamshere, Hayes, Downs, O'Donovan and Owen16 from the Clinical Records Interactive Search (CRIS) system, an anonymised case register derived from SLaM electronic case records. Follow-up with regard to continuing clozapine was carried on until clozapine discontinuation or 2 years after clozapine initiation, whichever occurred sooner. Post-discharge follow-up was continued from the date of discharge until the date clozapine was stopped or 1 year of treatment, whichever occurred sooner. Global clinical severity was rated retrospectively at clozapine prescription, using the CGI-I, by manual analysis of the electronic medical records. No information on the use of restraints was available for the historical cohort.

Adverse events

All SLaM patient records were scrutinised for documented adverse events (including when they first occurred in relation to the initiation date). Adverse events were defined as any unfavourable and unintended sign, symptom or disease noted on the electronic records that occurred during use of intramuscular clozapine or within 3 days from administration and that was not recorded on the manufacturer's summary product characteristics (https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/4411/smpc).

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was carried out with Stata/SE 15.0 for Mac.17 The percentage of patients who successfully initiated oral clozapine after intramuscular prescription was calculated. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were used to estimate and graph the time to clozapine discontinuation from intramuscular or oral clozapine prescription in both the intramuscular cohort and the comparison group, respectively. Patients were followed up on from the date of first intramuscular clozapine prescription and were censored after 2 years of follow-up or until 31 July 2019, whichever occurred sooner. All-cause discontinuation of oral clozapine was calculated, and all patients who were prescribed intramuscular clozapine were included, whether or not they received the drug intramuscularly. After checking proportional hazard assumptions, a Cox regression was used to model the association between intramuscular clozapine prescription and clozapine discontinuation. Propensity scores were used to address the issue of confounding by indication, and a fully adjusted Cox analysis was carried out with the propensity score included as a covariate. Propensity scores indicate the probability of being prescribed intramuscular clozapine based on patient characteristics (age, gender, diagnosis, length of illness, CGI-I score at clozapine prescription) and were calculated by logistic regression.

A separate survival analysis was set up to model post-discharge clozapine discontinuation rates, which were graphed with a Kaplan–Meier survival curve in both the intramuscular and comparison group, with time point zero set as the date of discharge. Patients were censored after 1 year of follow-up or until 31 July 2019, whichever occurred sooner. The discontinuation rates in the two groups were analysed with a Cox regression model adjusted for propensity scores, which were included in the analysis as a covariate.

Post hoc analysis with Kaplan–Meier survival curves was conducted to evaluate differences in discontinuation rates after intramuscular prescription between the subgroup of patients who were prescribed and administered intramuscular clozapine and those who had it prescribed but not administered. Post hoc Cox regression analysis was conducted to calculate the hazard of clozapine discontinuation in the two subgroups.

Ethical standards

This clinical effectiveness study was approved by the Drugs and Therapeutics Committee of SLaM, the locally designated approval committee for all non-interventional prescribing outcome audits. The local SLaM protocol for the use of intramuscular clozapine was approved by the Drugs and Therapeutics Committee.

Ethical approval for the use of CRIS as a research data-set was given by Oxfordshire Research Ethics Committee C (approval number 08/H0606/71). The patient-led CRIS oversight committee granted permission for the use of a previously identified, anonymised cohort of patients commencing oral clozapine to provide the comparison group data. Informed consent was not required as CRIS is an anonymised case register.

Results

Patient characteristics: intramuscular clozapine cohort

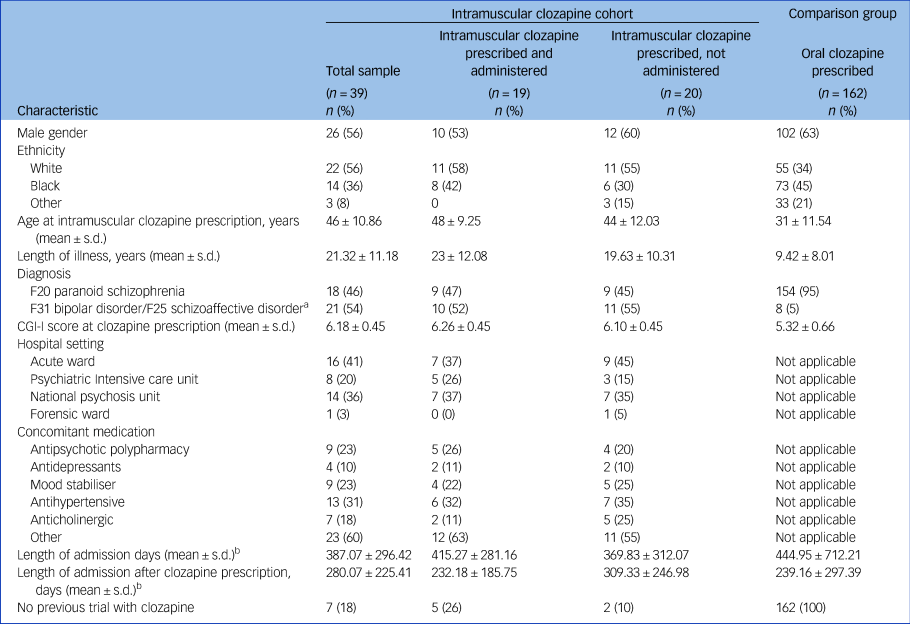

Data were available for 39 in-patients with a treatment-resistant psychotic disorder who had been prescribed intramuscular clozapine. Of these, 19 (49%) were administered at least one injection (median 2, range 1–56), whereas 20 (51%) preferred to receive oral clozapine when offered the enforced choice between oral and intramuscular administration. Of the patients who received more than one injection, seven (50%) were administered consecutively and seven (50%) received intramuscular intermittently with oral clozapine. Thirty-two patients (82% of our sample) had previously taken clozapine. Cohort characteristics are presented in Table 1. Table 2 summarises characteristics of intramuscular clozapine administrations in our sample.

Table 1 Demographic and clinical characteristics

Codes F20, F31 and F25 are from the ICD-10. CGI-I, Clinical Global Impression Improvement Scale.

a. Schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder combined to avoid presenting identifiable data.

b. Only included patients who were discharged during the study period.

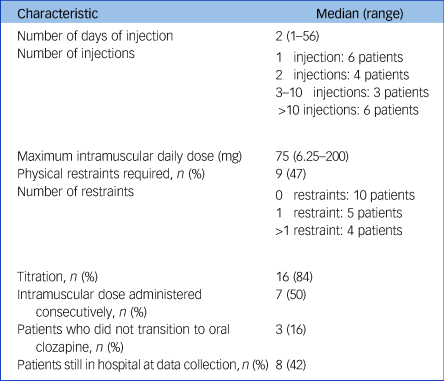

Table 2 Characteristics of intramuscular clozapine administrations

Among the 19 patients who received intramuscular clozapine, the median maximum daily intramuscular dose was 75 mg (range 6.25–200 mg), equivalent to 150 mg of oral clozapine. Most patients (n = 16, 84%) received the injection(s) during the titration period; either from the first dose (n = 11, 58%) or after refusing later doses (n = 5, 26%). Manual restraints by nursing staff were used in nine patients (47%) with a median of zero and a mean of two restraints per patient (zero restraints in ten patients, one restraint in five patients, more than one restraint in four patients). No mechanical restraints were used. The most common adverse event associated with intramuscular formulation was swelling at the injection site, which occurred in the three patients who had more than 29 injections (16%). Other side-effects reported in the patients’ notes were drowsiness in two patients (10%), urinary incontinence (one patient, 5%) and neutropenia (one patient, 5%). No side-effects associated with physical restraints were reported in the electronic notes, although psychological consequences were not explicitly investigated.

Patient characteristics: historical cohort

The comparison group included 162 patients who started oral clozapine while admitted to a SLaM hospital under the MHA 2008. They all fulfilled the criteria for a treatment-resistant psychotic disorder, and their characteristics are summarised in Table 1.

Transition from intramuscular to oral clozapine and discontinuation rates

In total, 36 patients (92%) eventually started oral clozapine after being prescribed the intramuscular formulation. Among those who received at least one injection, 16 (84%) were later switched to oral. The remaining three either continued to refuse oral clozapine despite intramuscular administrations or discontinued intramuscular clozapine because of adverse effects (neutropenia, recurrent pneumonia). The median number of days of injection before transition to oral was two (range 1–47).

In the intramuscular cohort, median follow-up was 694 (interquartile range (IQR) 481–720) days from intramuscular prescription date and 296 (IQR 0–365) days from discharge date. In the comparison group, mean follow-up was 720 days from the date of clozapine initiation and 365 days from discharge. In the subgroup of patients who were prescribed and administered intramuscular clozapine, median follow-up was 509 (IQR 302–720) days from prescription and 236 (IQR 0–365) days from discharge, whereas in the subgroup of patients who were prescribed but not administered intramuscular clozapine, mean follow-up was 683 (IQR 534–720) days from prescription and 287 (IQR 0–365) days from discharge.

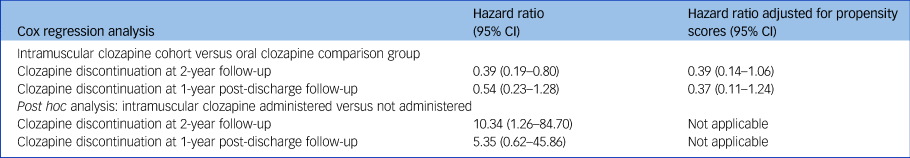

Fig. 1(a) displays a Kaplan–Meier survival curve for the clozapine discontinuation rates after clozapine prescription in the cohort of patients who were prescribed intramuscular clozapine and in the comparison group. Discontinuation rates at 2-year follow-up were lower in the cohort of patients who were initially prescribed intramuscular clozapine than in the comparison group (24% and 50%, respectively), with a reduced hazard of clozapine discontinuation (hazard ratio 0.39, 95% CI 0.19–0.80) although this became non-significant after the model was adjusted for propensity scores (hazard ratio 0.39, 95% CI 0.14–1.06). In a post hoc analysis, higher discontinuation rates were found in those who received the injection compared with those who chose to receive oral clozapine after being offered the enforced choice between the two formulations (52% and 6%, respectively; hazard ratio 10.34, 95% CI 1.26–84.70). The Kaplan–Meier survival curve is shown in Fig. 1(b). Table 3 summarises the results of the Cox regression analyses.

Fig. 1 Kaplan–Meier survival curves. (a) Clozapine discontinuation rates after intramuscular (intramuscular cohort) or oral (comparison group) clozapine prescription. (b) Post hoc analysis of clozapine discontinuation rates after intramuscular or oral (comparison group) clozapine prescription after subdividing patients according to whether they were administered intramuscular clozapine. (c) Clozapine discontinuation rates after discharge in the cohort and the comparison group. (d) Clozapine discontinuation rates after discharge subdivided by whether intramuscular clozapine was administered versus the comparison group of patients prescribed oral clozapine.

Table 3 Results from the Cox regression analyses

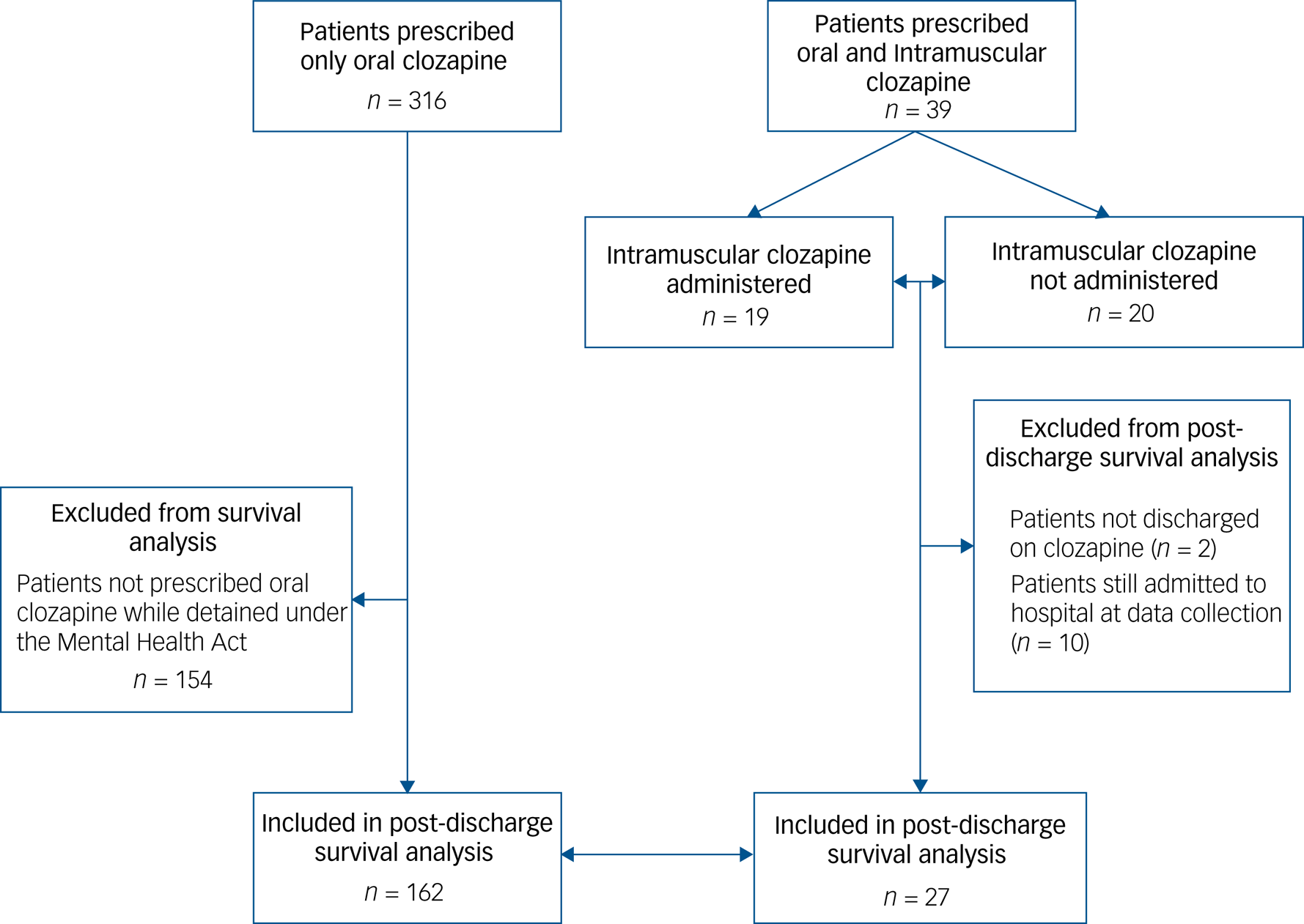

Data were available after discharge for 29 of the intramuscular patients (74%; five of which had received at least one injection) as the remaining ten (26%) were still in hospital at the end of the study. Twenty-two (76% of those discharged) patients were maintained on oral clozapine until the end of follow-up; in the comparison group, 81 out of 162 patients remained on clozapine 1 year after discharge. Among the seven patients who were clozapine-naïve at intramuscular prescription, three (43%) were still on oral clozapine at the end of follow-up.

Patients included in the post-discharge survival analysis are shown in Fig. 2. Discontinuation rates at 1 year after discharge for the intramuscular cohort and the comparison group were 21% and 44%, respectively (Fig. 1(c)). Figure 1(d) graphs the post hoc survival analysis for the subgroup of patients who were administered and those who were not administered intramuscular clozapine. Compared with the oral formulation, intramuscular clozapine prescription was associated with a non-significantly reduced risk of clozapine discontinuation after discharge, after adjusting for propensity scores (hazard ratio 0.37, 95% CI 0.11–1.24). Post hoc Cox regression analysis showed an increased risk of clozapine discontinuation after discharge in the subgroup of patients who were administered intramuscular clozapine compared with those prescribed but not administered intramuscular clozapine, although this was not statistically significant (adjusted hazard ratio 5.35, 95% CI 0.62–45.87).

Fig. 2 Study profile for post-discharge survival analysis.

In the entire cohort of 39 patients, eight (20%) discontinued clozapine treatment during the follow-up period. Four (10%) discontinued because of non-adherence or unknown reasons and four discontinued because of adverse effects (10%) unrelated to the intramuscular formulation, but rather to clozapine's established adverse effect profile (neutropenia, recurrent pneumonia).

On a practical level, the majority of patients who received intramuscular clozapine were administered less than ten injections (n = 13; 68%), with a discontinuation rate of 39% after 2 years of treatment. However, among the six patients who received more than ten injections, two (33%) switched to oral clozapine and remained on it at the end of follow-up, and four discontinued it. The maximum number of injections administered before successful transition to oral treatment was 47.

Among the nine patients who required manual restraints during intramuscular clozapine administration, seven remained on clozapine at follow-up and two discontinued it, one of which never agreed to transition from intramuscular to oral clozapine.

Discussion

In this retrospective clinical effectiveness study of patients prescribed intramuscular clozapine, 92% of patients were successfully initiated on oral clozapine after intramuscular prescription after a median of two intramuscular administrations. Of patients with sufficient follow-up data, 76% remained on clozapine at 2 years from initiation. Clozapine discontinuation rates at 2-year follow-up were similar to a comparison group of patients who were prescribed only oral clozapine under the MHA 2008 in routine clinical practice. Correspondingly, clozapine discontinuation rates of 21% were observed at 1-year follow-up post-discharge. This is at the lower end of that shown in previous studies, which demonstrate clozapine discontinuation rates between 16 and 66% across various countries.Reference Masuda, Misawa, Takase, Kane and Correll18

Clozapine has consistently been shown to provide superior therapeutic benefits in treatment-resistant psychotic disordersReference Siskind, McCartney, Goldschlager and Kisely1 and should therefore be offered to all patients that meet these criteria. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines highlight the importance of involving patients in decisions about the choice of medication.19 Nonetheless, some people diagnosed with a psychotic disorder lack insight and capacity to make an informed decision about optimal treatment options, particularly during acute illness, and may therefore make a non-capacitous decision to decline medication. Moreover, patients may be non-adherent as a direct response to delusional beliefs. There is compelling evidence to suggest that patients’ refusal of clozapine in treatment-resistant psychotic disorders may have a significant negative effect on their long-term outcomes,Reference Kane, Kishimoto and Correll20 and in the best interest of selected cases, enforced treatment may be the most appropriate option.

Presently, few naturalistic studies have demonstrated the potential of intramuscular clozapine in initiating treatment, with a total enrolment of approximately 100 patients.Reference Henry, Massey, Morgan, Deeks, Macfarlane and Holmes9–Reference Lokshin, Lerner, Miodownik, Dobrusin and Belmaker13 To our knowledge, this is the largest study in the UK to report the use of short-acting intramuscular clozapine for treatment initiation and maintenance in patients with a treatment-resistant psychotic disorder. Our study further adds to the evidence for intramuscular clozapine as a viable tool to allow patients whose illness is compromising their capacity to consent to appropriate treatment for their treatment-resistant psychotic disorder to access and benefit from clozapine.

Post-discharge discontinuation rates were as good as, or better than, a comparison group prescribed only oral clozapine. This suggests that the prescription of intramuscular clozapine may achieve long-term clinical improvement and adherence to oral medication, even in those patients who are initially reluctant to engage with clozapine treatment, and that this is maintained even in a less restrictive setting. Consistent with previous studies,Reference Henry, Massey, Morgan, Deeks, Macfarlane and Holmes9,Reference Schulte, Stienen, Bogers, Cohen, van Dijk and Lionarons11,Reference Lokshin, Lerner, Miodownik, Dobrusin and Belmaker13 our data found no evidence that intramuscular clozapine differs markedly from oral clozapine tolerability and adverse effects, with the one reported adverse event related to its formulation being swelling at the injection site. However, the lack of additional side-effects reported may be attributed to its short-term use, often during titration and therefore at low doses, and this study was not powered nor designed to assess safety.

In the observational cohort, over half of those who had been prescribed intramuscular clozapine chose to accept oral clozapine after being offered the choice between the two formulations. This finding is in line with an observational study by Hoge et al,Reference Hoge, Appelbaum, Lawlor, Beck, Litman and Greer21 according to which drug refusal developed into voluntary acceptance of treatment by most patients. Although preliminary, our data on discontinuation rates among those who did not require intramuscular administrations is in line with previous findingsReference Henry, Massey, Morgan, Deeks, Macfarlane and Holmes9,Reference Schulte, Stienen, Bogers, Cohen, van Dijk and Lionarons11 that the mere prescription of intramuscular clozapine can increase adherence to clozapine without the need of intramuscular administration. Post hoc analysis also showed that those patients who accepted oral clozapine when offered the intramuscular had lower discontinuation rates compared with patients who declined oral and were administered intramuscular clozapine. Although this result should be interpreted with caution because of small numbers, this may be attributed to a more entrenched attitude toward medication in the latter subgroup. Nevertheless, future qualitative work is required to understand the decision-making process underpinning a patient's decision to accept oral treatment when there is a choice between intramuscular and oral dispensation.

Enforcement of treatment in psychiatry remains an ethically and clinically contentious practice. Previous literature has raised questions about the risks and benefits of enforcing clozapine treatment.Reference Barnes22 This debate is ongoing, and it is beyond the scope of this article. However, in an investigation on patients’ perception towards their involuntary admission, O'Donoghue et alReference O'Donoghue, Lyne, Hill, Larkin, Feeney and O'Callaghan23 found that before discharge 72% of patients reported admission to have been necessary and almost 80% felt that the received treatment had been beneficial. Furthermore, previous studies have demonstrated improvement in in-patients with schizophrenia, irrespective of whether they received treatment voluntarily or involuntarily.Reference Steinert and Schmid24 Of interest, patients treated involuntarily tended to show even greater symptom improvement than voluntary patients.Reference Steinert and Schmid24 Consistent with our findings, a recent small-scale study in the UK demonstrated positive outcomes with compulsory clozapine treatment by nasogastric administration. Nevertheless, the intramuscular route remains well-established in clinical practice and avoids the considerably more invasive and distressing nature of nasogastric administration and its greater resource requirements.Reference Till, Selwood and Silva8

Although our sample is too small to draw any firm conclusions, our findings may justify safely persisting with intramuscular clozapine to achieve transition to oral formulation, despite a prolonged refusal of oral treatment. Nevertheless, individual-based decisions are paramount to ensure the best interest of every patient.

In our study, the use of manual restraints by nursing staff did not appear to influence clozapine discontinuation rates. Clozapine treatment has been shown to demonstrate a reduction in incidents of aggression and subsequent restraints, but whether this is comparable with intramuscular administration remains unanswered. Furthermore, because of the lack of a formal evaluation, the psychological effect of restraint on both patients and nursing staff could not be investigated in our study.

Our experience also suggests intramuscular clozapine can be used to achieve oral clozapine initiation and avoid treatment interruption when used both consecutively and intermittently with oral clozapine. Previous authors have shown clozapine to be a cost-effective therapy in treatment-resistant schizophrenia,Reference Hayhurst, Brown and Lewis25 it is likely that an economic evaluation will demonstrate that intramuscular clozapine prescription is highly cost-effective, especially in light of the absence of alternative treatments for this population.

Despite the encouraging evidence generated from our study, it must be emphasised that those who declined treatment did not form a homogenous group and might have done so for a variety of reasons that warrant further examination before any actions are taken. Similarly, different factors could have played a role in favouring a transition from intramuscular to oral clozapine, such as clinician–patient relationship or familiarity with nursing staff providing medication. In addition, relevant differences were observed between the two study groups. The patients offered intramuscular clozapine had greater severity (CGI-I score mean 6.18, s.d. 0.45) and longer duration of illness (mean 21.32 years, s.d. 11.18 years) than the comparison population (CGI-I score 5.35 ± 0.64; duration of illness 9.42 ± 8.01 years). However, previous studies on patients with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder have suggested that those who refuse treatment tend to be more symptomatic and with worse functioning than those who agree to treatment.Reference Sendt, Tracy and Bhattacharyya26 Furthermore, only 18% of our patients were clozapine-naïve at intramuscular clozapine prescription, which might reflect the fact that intramuscular clozapine is more likely to be recommended in patients with a previous good response to clozapine. Nevertheless, previous work has demonstrated clinical effectiveness in clozapine-naïve patients.Reference Schulte, Stienen, Bogers, Cohen, van Dijk and Lionarons11

Limitations and future research

The most important limitation of our study is the small sample size; however, this is consistent with previous studies evaluating intramuscular clozapine use.Reference Henry, Massey, Morgan, Deeks, Macfarlane and Holmes9,Reference Schulte, Stienen, Bogers, Cohen, van Dijk and Lionarons11,Reference Lokshin, Lerner, Miodownik, Dobrusin and Belmaker13 This limits the interpretability of our results, as evidenced by the fairly large confidence interval around the results. The limited number of patients included in the study has also prevented us from conducting further post hoc analysis that could have been useful to identify specific subgroups of patients who could benefit from intramuscular clozapine administration. Second, as follow-up data collection ended in July 2019, 26% (n = 10) of patients could not be followed up on after discharge because they were still in hospital. In addition, not all patients who were discharged had sufficient follow-up, as they were in the community for less than 1 year at data collection. Furthermore, the naturalistic nature of our study meant that clozapine continuation post-discharge was confirmed by prescription refills of oral clozapine and adherence to haematological monitoring requirements as opposed to the more objective method of measuring serum clozapine levels. Equally, the quality of data available for reasons for clozapine discontinuation were limited to the information provided in electronic clinical record systems by the patients’ clinical teams. Our study needs to be replicated prospectively in a larger sample size, and possibly with a longer follow-up period.

Another limitation lies in the comparator group. Patients who are prescribed intramuscular clozapine are intrinsically different from those who accept oral clozapine, being less adherent and willing to accept any kind of treatment. Our comparator group differed from the cohort in age, and they had longer length of illness and higher CGI-I at clozapine initiation. We addressed this confounding by indication by calculating and adjusting for propensity scores in the Cox regression analyses, although some potential confounders may not have been measured and hence not included in the adjustment. Nonetheless, as the intramuscular clozapine cohort included more severely unwell patients than the historical comparator, this would have, if anything, biased the results in favour of the latter. Another difference to highlight in the comparator group is the involvement of patients who were clozapine-naïve, whereas our intramuscular clozapine cohort only had 18% of patients who had never taken clozapine before. It could be argued that the historical cohort covers a different timeframe compared with the intramuscular clozapine cohort. Although this should be highlighted as a limitation, there has not been any major recent implementation of clozapine-focused services in SLaM.

Because of the retrospective nature of the study, we did not have standardised scales on side-effects, nor could we collect data on patients’ subjective experience of intramuscular clozapine treatment, which would have enhanced the study findings. Further research is needed to explore patients’ perspectives on intramuscular treatment both at the time of administration and longer term. In particular, qualitative analysis would add to our understanding and reveal avenues for more focused quantitative work. Finally, future work should focus on which subgroups of patients are more likely to benefit from intramuscular clozapine prescription to support more targeted approaches to interventions.

In conclusion, the main finding of our study is that most of patients prescribed intramuscular clozapine were able to successfully initiate oral clozapine after intramuscular prescription, with half of patients not requiring administration of the injection. Discontinuation rates after initial intramuscular clozapine prescription were consistent with current literature and similar to the comparison group. Discontinuation rates post discharge did not differ from those who were only prescribed oral treatment with clozapine from initiation. Our data, although preliminary, suggest that prescribing intramuscular clozapine is a viable short-term tool to allow patients to access oral clozapine, the most effective available treatment for treatment-resistant psychotic disorders. Pain and swelling at injection site were the only reported side-effects specific to the intramuscular formulation and occurred only in a minority of patients. Additional evidence, possibly derived from robust prospective studies, is needed to provide new and more definite insights about the transition from intramuscular to oral formulations of clozapine.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at http://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.115

Data availability

Authors had free access to the study data. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, C.C., upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

This paper represents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Author contributions

C.C., E.W., D.M.T., A.S. and J.H.M. contributed to the conception and design of the study. C.C., E.O., S.E.L. and O.D. collected and analysed the data. F.G., S.S.S. and J.O. took part in the interpretation of the data. All authors contributed to the drafting and revision of the manuscript.

Declaration of interest

None.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.115.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.