There are over 10 million prisoners worldwide, Reference Walmsley1 a population that has been growing by about 1 million per decade. In 2008, the USA had the largest number of people imprisoned at 2.3 million and the highest rate per head of population (at 756 per 100 000 people compared with a median of 145 per 100 000 worldwide), and China, Russia, Brazil and India had more than a quarter of a million prisoners each. Reference Walmsley1 It has been widely reported that prisoners have elevated rates of psychiatric disorders compared with the general population, including for psychosis, depression, personality disorder and substance misuse, which are risk factors for elevated suicide rates, Reference Baillargeon, Penn, Thomas, Temple, Baillargeon and Murray2,Reference Fazel, Cartwright, Norman-Nott and Hawton3 premature mortality on release from prison Reference Kariminia, Law, Butler, Corben, Levy and Kaldor4 and increased reoffending rates. Reference Fazel and Yu5,Reference Baillargeon, Binswanger, Penn, Williams and Murray6 It is estimated that suicide rates within prison are increased four to five times Reference Fazel, Grann, Kling and Hawton7 and deaths within the first week of release 29-fold higher Reference Binswanger, Stern, Deyo, Heagerty, Cheadle and Elmore8 than rates in the general population. Further, a recent review found that reoffending rates are increased by 40% in offenders with psychotic disorders compared with non-mentally ill offenders. Reference Fazel and Yu5

A previous systematic review estimated that the prevalence of psychosis was typically 4% in prisoners of both genders, and that of major depression was 10% in men and 12% in women. Reference Fazel and Danesh9 However, this review is now a decade old, and, as many psychiatric institutions have continued to reduce their bed numbers, Reference Priebe, Frottier, Gaddini, Kilian, Lauber and Martínez-Leal10 a number of commentators have suggested that rates of severe mental illness have been increasing over time in prisoners, Reference Dressing, Kief and Salize11 although empirical evidence in support of this is inconsistent Reference Bradley-Engen, Cuddeback, Gayman, Morrissey and Mancuso12 and experts have suggested that measures introduced by the World Health Organization and other international humanitarian agencies have improved prison care. Reference Levy13 In addition, there has been no review, to our knowledge, of the mental health of prisoners in low–middle-income countries, although the vast majority of prisoners now live in such countries. Reference Walmsley1 As there is a substantial body of new evidence, Reference Moher and Tsertsvadze14 we have conducted a new systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of psychosis and major depression, and used subgroup analyses and meta-regression to explore possible sources of heterogeneity between studies. We hypothesise that there has been an increase in the rates of psychosis and major depression over time, and that low–middle-income countries have higher prevalences of these conditions due to their less resourced community and prison healthcare services. Reference Saxena, Thornicroft, Knapp and Whiteford15

Method

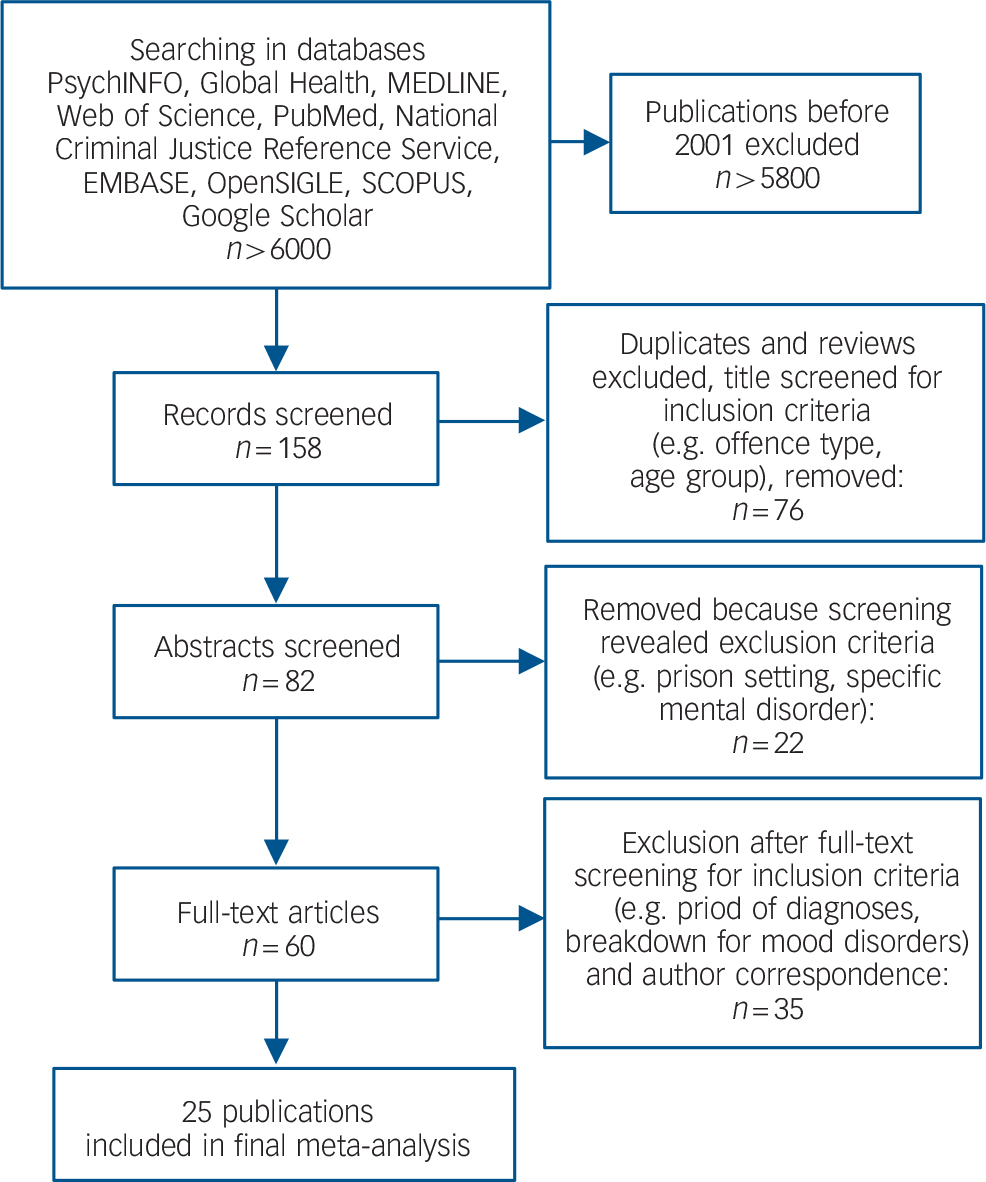

We identified publications estimating the prevalence of psychotic disorders (including psychosis, schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorders, manic episodes) and major depression among prisoners that were published between 1 January 1966 and 31 December 2010. For the period 1 January 1966 to 31 December 2000, methods are described in a previous systematic review conducted by one of the authors (S.F.). Reference Fazel and Danesh9 For the update and expanded review, from 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2010, we used the following databases: PsycINFO, Global Health, MEDLINE, Web of Science, PubMed, National Criminal Justice Reference Service, EMBASE, OpenSIGLE, SCOPUS, Google Scholar, scanned references and corresponded with experts in the field (Fig. 1). Key words used for the database search were the following: mental*, psych*, prevalence, disorder, prison*, inmate, jail, and also combinations of those. Non-English language articles were translated. We followed PRISMA criteria. Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman and The16

FIG. 1 Flow diagram showing the different steps involved in searching for relevant publications (2001–2010).

Inclusion criteria were the: (a) study population was sampled from a general prison population; (b) diagnoses of the relevant disorders were made by clinical examination or by interviews using validated diagnostic instruments; (c) diagnoses met standardised diagnostic criteria for psychiatric disorders based on the ICD or the DSM; (d) prevalence rates were provided for the relevant disorders in the previous 6 months.

In order to include unselected, representative and generalisable prison samples we only selected studies that conducted a diagnostic interview with a general prison population. We excluded those studies that used a screening tool before conducting the diagnostic interview Reference Baillargeon, Binswanger, Penn, Williams and Murray6,Reference O'Keefe and Schnell17,Reference Steadman, Osher, Robbins, Case and Samuels18 (as this may lead to an underestimate if the screening tool had poor sensitivity or overestimates if the tool had poor specificity). We also excluded sampled selected populations, for example by offence type Reference Kanyanya, Othieno and Ndetei19,Reference Kugu, Akyuz and Dogan20 (as there is evidence that selecting some offender groups may also lead to overestimates, which is particularly the case for murder and attempted murder Reference Fazel and Grann21 ), or age group Reference Fazel, Hope, O'Donnell, Piper and Jacoby22 (including solely juvenile prisoners Reference Ajiboye, Yussuf and Issa23 or prisoners who were in healthcare settings Reference Morgan, Fisher, Duan, Mandracchia and Murray24 ). For example, one study that used a screening tool to identify mentally ill prisoners and was excluded reported a prevalence of 32% for schizophrenia. Reference Lamb, Weinberger, Marsh and Gross25 Studies that did not separate sentenced from remand prisoners in their report Reference Segagni Lusignani, Giacobone, Pozzi, Dal Canton, Alecci and Carra26 and duplicates were excluded. In this update, we did not include personality disorder due to the high heterogeneity reported in the previous work. Reference Fazel and Danesh9 For substance misuse and post-traumatic stress disorder, there are more recent reviews Reference Fazel, Bains and Doll27,Reference Goff, Rose and Purves28 and a substantial body of new work has not emerged since their publication. Reference Abdalla-Filho, De Souza, Tramontina and Taborda29

Data extraction

We extracted information on the year of interview, geographical location, gender, remand/detainee (including jail inmates) or sentenced prisoner, average age, method of sampling, sample size, participation rate, type of interviewer, diagnostic instrument, diagnostic criteria (ICD v. DSM), numbers diagnosed with psychotic disorders (ICD-10: F20.xx–F29.xx, F30.xx; DSM-IV: 293.xx, 295.xx), and major depression (ICD-10, F 32.xx, F33.xx; DSM-IV: 296.2x, 296.3x). Where there was schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders reported separately, we combined them to produce a single prevalence. For one publication, Reference Falissard, Loze, Gasquet, Duburc and de Beaurepaire30 we collated ‘Dépression endogène-Mélancolie’, ‘Etat dépressif chronique’ and ‘Symptômes psychotiques contemporains des épisodes thymiques’ as indicating major depression. The data from each of the identified publications were subdivided into four samples (men v. women, remand/detainee v. sentenced prisoners). In contrast to our previous review, we included data on low–middle-income countries 31 and whether the clinical diagnostic interview was conducted within 2 weeks of arrival into the prison (which may influence prevalence rates and also provides an estimate of mental health needs on reception to prison). For the update, we examined rates of comorbidity with substance misuse. The data extraction was done by two researchers independently (K.S. and K.W.). For further clarification about specific studies, we corresponded directly with the authors of the studies.

Data analysis

We analysed sources of heterogeneity by subgroup and meta-regression analysis using dichotomous and continuous variables. The year that the interview was conducted and the average age of the prisoners were analysed as continuous variables. Sample size and response rate were analysed as both dichotomous and continuous variables. As the median of reported response rates was 81%, we defined ‘low’ as ⩽80% v. ‘high’ as >80%). The following were analysed only as dichotomous variables: gender, prisoner type (detainees/remand v. sentenced prisoners), reception status (interviewed in the first 2 weeks of reception v. the rest), type of interviewer (psychiatrist v. non-psychiatrist), diagnostic instrument (clinical examination v. semi-structured interview using a diagnostic tool) and classification criteria (ICD v. DSM). Geographical location was analysed as low–middle-income v. high-income country. 31 We included the US studies within the high-income country group. Also, we conducted an additional separate analysis of US studies (v. rest of world and v. rest of high-income countries) for three reasons: first, there are over 2 million prisoners there (around a fifth of the world prisoner population); second, they constituted 30% of the included studies in the review; and third, mentally disordered prisoners in the USA are less likely to be diverted because of judicial and legal reasons, and hence this may contribute to higher prevalence rates. Reference Baillargeon, Binswanger, Penn, Williams and Murray6

We used a recent method for further examination of heterogeneity, which involves removing up to four outliers and testing whether this reduces I 2 values to below 50%, and then investigating in more detail the study characteristics of these outliers. Reference Patsopoulos, Evangelou and Ioannidis32

We calculated pooled prevalence estimates and their 95% confidence intervals and transformed the zero cells to 0.5 in order to calculate prevalences as per standard methods. Reference Sweeting, Sutton and Lambert33 Meta-analyses for prevalences were conducted by gender and prisoner status. We measured the heterogeneity between studies with Cochran's Q (reported with a chi-squared value and P-value) and the I 2 statistic (with 95% confidence intervals) Reference Ioannidis, Patsopoulos and Evangelou34 and used random-effects models for summary statistics as heterogeneity was high (I 2>75%). Reference Higgins and Thompson35,Reference Higgins, Thompson, Deeks and Altman36 The I 2 is an estimate of the proportion of the total variation across studies that is beyond chance. In situations with high between-study heterogeneity, the use of random-effects models is recommended as it produces study weights that primarily reflect the between-study variation and thus provide close to equal weighting. Univariate and multivariate meta-regression analyses were used to explore possible sources of heterogeneity among studies. Reference Ioannidis, Patsopoulos and Rothstein37 Factors in univariate meta-regression with P-values of <0.1 were included in the final model. We also conducted a test of funnel plot asymmetry (Egger's test) for publication bias using the publication (rather than the sample) as the unit of measurement. A funnel plot is a plot of the estimated prevalence against the sample size of the included studies. Egger's test can reveal a symmetric or asymmetric funnel plot. The latter indicates the existence of a significant publication bias or a systematic heterogeneity between studies. Reference Egger, Smith, Schneider and Minder38 All analyses were done in STATA statistical software, version 11.1 on Windows.

Results

Study characteristics

The final data-set consisted of 81 publications, 56 based on the previous review from the period 1966–2001 Reference Andersen, Sestoft, Lillebaek and Gabrielsen39–Reference Hurwitz and Christiansen94 and 25 new ones (online Table DS1). Reference Falissard, Loze, Gasquet, Duburc and de Beaurepaire30,Reference Arnab, Prativa and Ray95–Reference Alevizopoulus and Igoumenou118 These publications provided data on 109 samples that included a total of 33 588 prisoners. Of these, 28 361 (84.4%) were male. The overall weighted mean age was 30.5 years. The studies were conducted in 24 different countries, 8 of which are classified as low–middle-income countries: Brazil, Reference Ponde, Cruz Freire and Santos Mendonca108 Dubai, Reference Ghubash and El-Rufaie93 India, Reference Arnab, Prativa and Ray95,Reference Sharma, Nijhawan, Sharma and Sushil109 Iran, Reference Assadi, Noroozian, Pakravannejad, Yahyazadeh, Aghayan and Shariat96 Kuwait, Reference Fido and al-Jabally92 Malaysia, Reference Zahari, Hwan Bae, Zainal, Habil, Kamarulzaman and Altice116 Mexico Reference Bermúdez, Romero Mendoza, Rodríguez Ruiz, Durand-Smith and Saldívar Hernández97 and Nigeria. Reference Agbahowe, Ohaeri, Ogunlesi and Osahon91

There were 72 studies from high-income countries. There were 25 studies from the USA, Reference Birmingham, Mason and Grubin41,Reference Daniel, Robins, Reid and Wilfley48,Reference DiCataldo, Greer and Profit51,Reference Eyestone52,Reference Gibson, Holt, Fondacaro, Tang, Powell and Turbitt54–Reference Guy, Platt, Zwerling and Bullock57,Reference Harper and Barry59,Reference Hyde and Seiter62–Reference Jordan, Schlenger, Fairbank and Caddell64,Reference Krefft and Brittain67,Reference Neighbors, Williams, Gunnings, Lipscomb, Broman and Lepkowski73,Reference Powell, Holt and Fondacaro75,Reference Poythress, Hoge, Bonnie, Monahan, Eisenberg and Feucht-Haviar76,Reference Robins and Reiger79,Reference Schuckit, Hermann and Schuckit82,Reference Simpson, Brinded, Laidlaw, Fairley and Malcolm83,Reference Swank and Winer85–Reference Washington and Diamond88,Reference Gunter, Arndt, Wenman, Allen, Loveless and Sieleni104,Reference Trestman, Ford, Zhang and Wiesbrock112 3 from Canada, Reference Bland, Newman, Dyck and Orn42,Reference Motiuk and Porporino72,Reference Roesch, Davies, Lloyd-Bostock, McMurran and Wilson80 5 from Australia, Reference Bartholomew, Brain, Douglas and Reynolds40,Reference Denton50,Reference Herrman, McGorry, Mills and Singh60,Reference Hurley and Dunne61,Reference Butler and Allnutt99 and 1 from New Zealand. Reference Brinded, Stevens, Mulder, Fairley, Malcolm and Wells44 The remaining studies were conducted in Europe including eight in England and Wales, Reference Brooke, Taylor, Gunn and Maden45,Reference Faulk53,Reference Maden, Taylor, Brooke and Gunn69,Reference Maden, Swinton and Gunn70,Reference Robertson78,Reference Watt, Tomison and Torpy89,Reference Wilkins and Coid90,Reference Parsons, Walker and Grubin106 six in Ireland, Reference Mohan, Scully, Collins and Smith71,Reference Smith, O'Neill, Tobin, Walshe and Dooley84,Reference Curtin, Monks, Wright, Duffy, Linehan and Kennedy100,Reference Duffy, Linehan and Kennedy102,Reference Linehan, Duffy, Wright, Curtin, Monks and Kennedy105,Reference Wright, Duffy, Curtin, Linehan, Monks and Kennedy115 three in Scotland, Reference Bluglass43,Reference Cooke47,Reference Davidson, Humphreys, Johnstone and Owens49 and a number in The Netherlands, Reference Bulten46,Reference van Panhuis74,Reference Schoemaker and VanZessen81,Reference Bulten, Nijman and van der Staak98 Finland, Reference Haapasalo58,Reference Joukamaa65,Reference Joukamaa66 Germany, Reference Dudeck, Kopp and Kuwert101,Reference von Schoenfeld, Schneider, Schroder, Widmann, Botthof and Driessen113,Reference Watzke, Ullrich and Marneros114 Denmark, Reference Andersen, Sestoft, Lillebaek and Gabrielsen39,Reference Hurwitz and Christiansen94 Italy, Reference Piselli, Elisei, Murgia, Quartesan and Abram107,Reference Zoccali, Muscatello, Bruno, Cambria and Cavallaro117 Greece, Reference Fotiadou, Livaditis, Manou, Kaniotou and Xenitidis103,Reference Alevizopoulus and Igoumenou118 Austria, Reference Stompe, Brandstätter, Ebner and Fischer-Danzinger110 France, Reference Falissard, Loze, Gasquet, Duburc and de Beaurepaire30 Norway, Reference Rasmussen, Storsaeter and Levander77 Spain Reference Vicens, Tort, Dueñas, Muro, Pérez-Arnau and Arroyo111 and Sweden. Reference Levander, Svalenius and Jensen68

Nine studies reported results from interviews carried out within 2 weeks of arrival into the prison, Reference Bulten, Nijman and van der Staak98–Reference Curtin, Monks, Wright, Duffy, Linehan and Kennedy100,Reference Duffy, Linehan and Kennedy102,Reference Gunter, Arndt, Wenman, Allen, Loveless and Sieleni104,Reference Parsons, Walker and Grubin106,Reference Stompe, Brandstätter, Ebner and Fischer-Danzinger110,Reference Trestman, Ford, Zhang and Wiesbrock112,Reference Wright, Duffy, Curtin, Linehan, Monks and Kennedy115 two of them without giving information about the prisoner type (remand/detainee or sentenced). Reference Butler and Allnutt99,Reference Wright, Duffy, Curtin, Linehan, Monks and Kennedy115

Psychotic illnesses

We identified 99 samples from 74 studies that reported rates of psychotic illnesses and included a total of 30 635 prisoners. Reference Falissard, Loze, Gasquet, Duburc and de Beaurepaire30,Reference Andersen, Sestoft, Lillebaek and Gabrielsen39–Reference DiCataldo, Greer and Profit51,Reference Faulk53–Reference Guy, Platt, Zwerling and Bullock57,Reference Harper and Barry59–Reference James, Gregory, Jones and Rundell63,Reference Joukamaa65–Reference Teplin, Abram and McClelland87,Reference Watt, Tomison and Torpy89–Reference Fido and al-Jabally92,Reference Hurwitz and Christiansen94–Reference Assadi, Noroozian, Pakravannejad, Yahyazadeh, Aghayan and Shariat96,Reference Bulten, Nijman and van der Staak98,Reference Curtin, Monks, Wright, Duffy, Linehan and Kennedy100–Reference Alevizopoulus and Igoumenou118 Overall, we calculated a random-effects pooled prevalence of 3.6% (95% CI 3.1–4.2) in male prisoners (1120 of 26 814 individuals), and 3.9% (95% CI 2.7–5.0) in female prisoners (182 of 3821 individuals) (Table 1). There was significant heterogeneity among these studies in the male (χ2 = 416, P<0.0001, I 2 = 83%, 95% CI 79–86) and female prisoners (χ2 = 86, P<0.0001, I 2 = 68%, 95% CI 54–79).

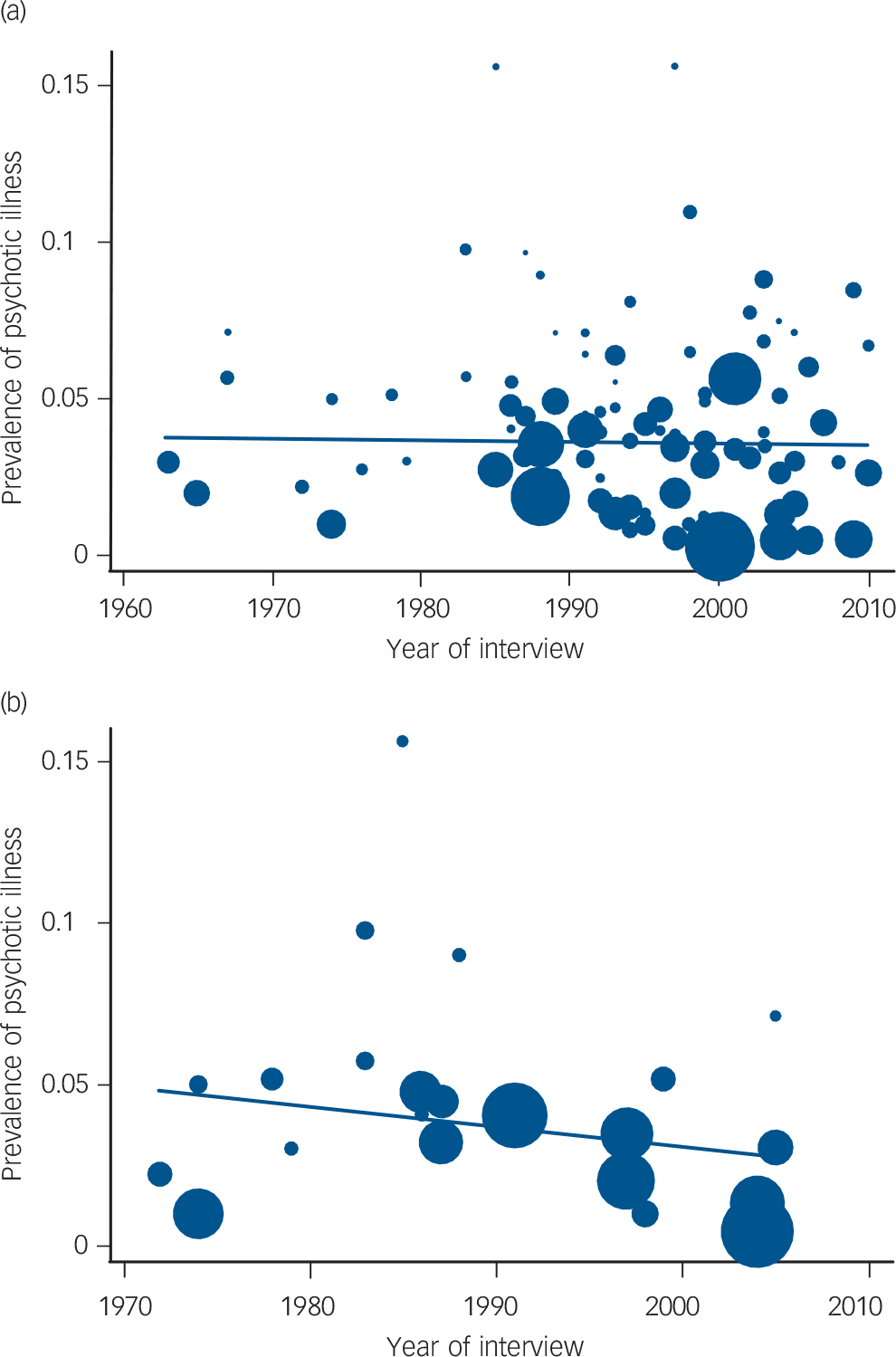

There was a significant difference in the prevalences in low–middle-income countries (5.5%, 95% CI 4.2–6.8) compared with high-income countries (3.5%, 95% CI 3.0–3.9) (Fig. 2), confirmed by meta-regression (β = 0.0204, s.e.(β) = 0.0095, P = 0.035) (Table 2). We did not find any difference in prevalences between male and female prisoners, between detainees/remand and sentenced prisoners, and no statistically significant change in prevalence over time (β = –0.0001, s.e.(β) = 0.0002, P = 0.84) (Fig. 3). When we looked specifically at US studies (17 samples), there also appeared to be no change over time (β = –0.0006, s.e.(β) = 0.0005, P = 0.24). There was evidence of an asymmetric funnel plot (Egger's test, t = 239.32, s.e.(t) = 0.0044, P<0.001).

Major depression

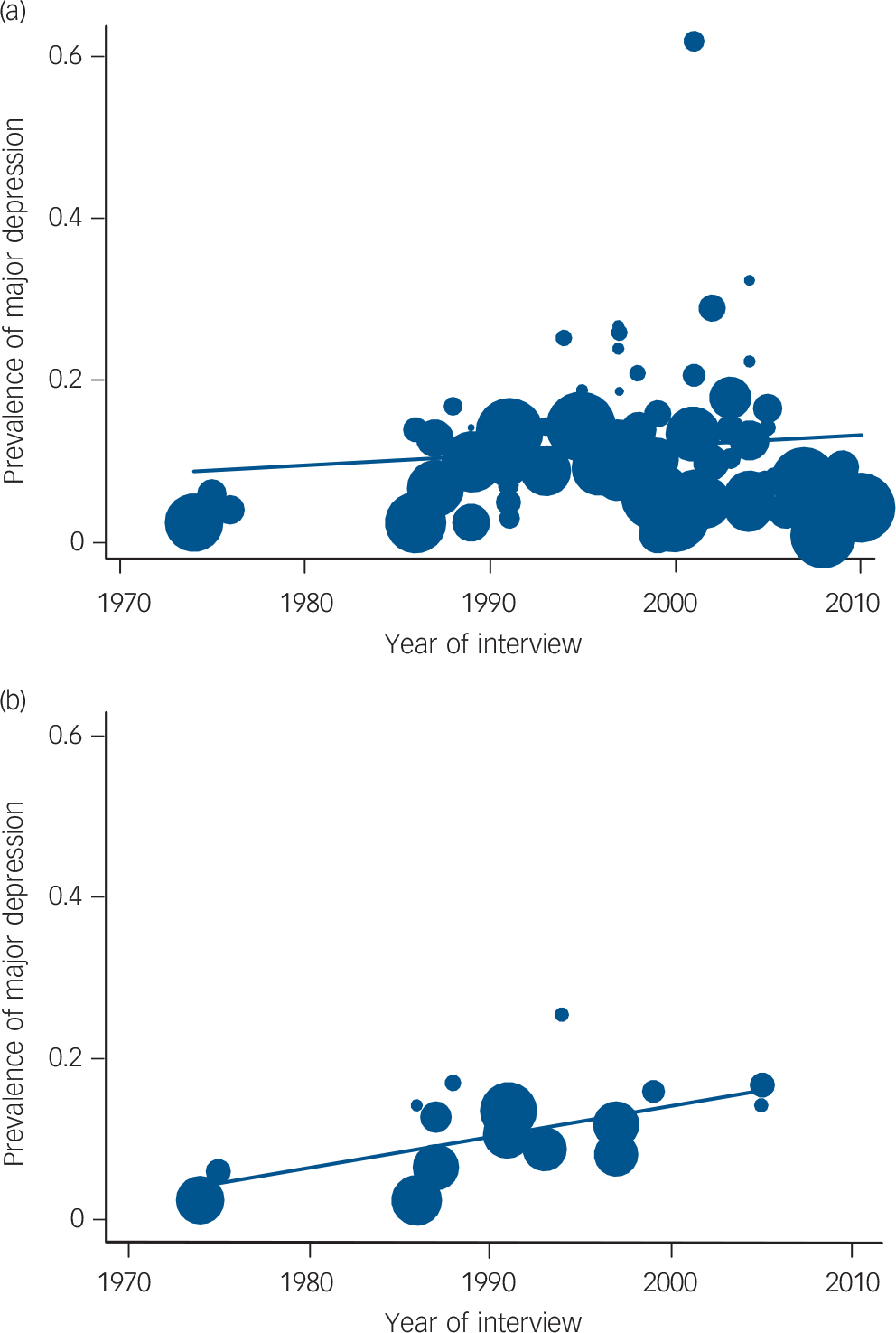

We identified 54 publications that reported rates of major depression in 20 049 prisoners. Reference Falissard, Loze, Gasquet, Duburc and de Beaurepaire30,Reference Andersen, Sestoft, Lillebaek and Gabrielsen39,Reference Bland, Newman, Dyck and Orn42,Reference Brinded, Stevens, Mulder, Fairley, Malcolm and Wells44–Reference Bulten46,Reference Daniel, Robins, Reid and Wilfley48,Reference Denton50–Reference Gibson, Holt, Fondacaro, Tang, Powell and Turbitt54,Reference Haapasalo58,Reference Herrman, McGorry, Mills and Singh60–Reference Hyde and Seiter62,Reference Jordan, Schlenger, Fairbank and Caddell64,Reference Mohan, Scully, Collins and Smith71,Reference Neighbors, Williams, Gunnings, Lipscomb, Broman and Lepkowski73,Reference Powell, Holt and Fondacaro75–Reference Rasmussen, Storsaeter and Levander77,Reference Robins and Reiger79–Reference Simpson, Brinded, Laidlaw, Fairley and Malcolm83,Reference Teplin, Abram and McClelland87–Reference Ghubash and El-Rufaie93,Reference Assadi, Noroozian, Pakravannejad, Yahyazadeh, Aghayan and Shariat96–Reference Ponde, Cruz Freire and Santos Mendonca108,Reference Stompe, Brandstätter, Ebner and Fischer-Danzinger110,Reference Vicens, Tort, Dueñas, Muro, Pérez-Arnau and Arroyo111,Reference von Schoenfeld, Schneider, Schroder, Widmann, Botthof and Driessen113–Reference Zahari, Hwan Bae, Zainal, Habil, Kamarulzaman and Altice116,Reference Alevizopoulus and Igoumenou118 Overall, 10.2% (95% CI 8.8–11.7) of male prisoners (1686 of 16 021 individuals) and 14.1% (95% CI 10.2–18.1) of female prisoners (605 of 4028) were diagnosed with major depression (Fig. 4). There was significant heterogeneity among these studies in males (χ2 = 541, P<0.0001, I 2 = 91%, 95% CI 89–93) and also in females (χ2 = 307, P<0.0001, I 2 = 93%, 95% CI 90–94). Even after the exclusion of four outliers in both genders, the I 2 remained above 50%.

There was no significant difference in the prevalence of depression between men and women. However, there appeared to be higher prevalences in those studies using DSM criteria and in low–middle-income countries, confirmed on univariate meta-regression (Table 2). Whereas there was no evidence for rates of major depression changing over time in the non-US samples, the prevalence of depression appeared to be increasing over time in the US samples, of which there were 17 from 1970 to 2010 (β = 0.0038, s.e.(β) = 0.0013, P = 0.008) (Fig. 5).

In a multivariate meta-regression analysis combining both income group and classification criteria, the finding of a higher prevalence rate in low–middle-income countries remained significant only for women prisoners and was based on a single Mexican study. Reference Bermúdez, Romero Mendoza, Rodríguez Ruiz, Durand-Smith and Saldívar Hernández97 In the US studies, multivariate meta-regression was not possible as all the samples that reported information on classification criteria used DSM criteria. However in the non-US and high-income samples, classification criteria still remained significant when income group was included in the model and DSM studies reported higher prevalences of depression (β = –0.0645, s.e.(β) = 0.0282, P = 0.026). There was evidence of an asymmetric funnel plot (t = 27.78, s.e.(t) = 0.0452, P<0.001).

Comorbidity

There were five publications since 2001 that reported rates of comorbidity in prisoners. Reference Assadi, Noroozian, Pakravannejad, Yahyazadeh, Aghayan and Shariat96,Reference Bermúdez, Romero Mendoza, Rodríguez Ruiz, Durand-Smith and Saldívar Hernández97,Reference Butler and Allnutt99,Reference Duffy, Linehan and Kennedy102,Reference Piselli, Elisei, Murgia, Quartesan and Abram107 These rates ranged from 20.4 to 43.5% in those with any mental disorder who had comorbid substance misuse, from 13.6 to 95.0% in prisoners with psychotic illnesses with comorbid substance misuse, and 9.2 to 82.5% in individuals with mood disorders and major depression with concurrent substance misuse.

Discussion

Main findings

We report a systematic review of the prevalence of psychosis and depression in prisoners based on 109 separate samples (from 81 publications) based on 33 588 prisoners. In addition, we have, for the first time to our knowledge, reviewed research in low- and middle-income countries (based on 5792 prisoners) and employed meta-regression analyses to explore sources of heterogeneity between studies. In particular, we have examined whether rates of mental illness in prisoners have been increasing over time.

TABLE 1 Pooled prevalances for psychosis and major depression in prisoners

| Variable | Psychosis, % (95% CI) |

Major depression,

% (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 3.7 (3.2–4.1) | 11.4 (9.9–12.8) |

| Gender of inmates | ||

| Male | 3.6 (3.1–4.2) | 10.2 (8.8–11.7) |

| Female | 3.9 (2.7–5.0) | 14.1 (10.2–18.1) |

| Prisoner status | ||

| Sentenced prisoners | 3.7 (3.0–4.2) | 10.5 (8.8–12.1) |

| Remand prisoners (detainees) | 3.5 (4.2–6.8) | 12.3 (9.5–15.1) |

| Country | ||

| Low/middle income | 5.5 (4.2–6.8) | 22.5 (10.6–34.4) |

| High income | 3.5 (3.0–3.9) | 10.0 (8.7–11.2) |

FIG. 2 Meta-analysis of the prevalence of psychotic illnesses in prisoners by country group (low–middle income v. high income).

Weights are from random-effects analysis. Smaller studies: n<250. ES, prevalence.

Our main findings were that rates of psychosis in prisoners were significantly higher in low- and middle-income countries than in high-income ones (5.5% in low–middle- v. 3.5% in high-income nations). Contrary to expert opinion, 119 there were no significant differences in rates of psychosis and depression between male and female prisoners or between detainees (or remand) and sentenced prisoners. In the 17 US samples included, there appeared to be an increasing prevalence of depression over the 31 years covered by these particular studies (1974–2005). In addition, we found no differences in depression rates between men and women, detainees (or remand) and sentenced prisoners, or other study characteristics that may have explained heterogeneity. The overall prevalences of 3.7% of male and female prisoners with a psychotic illness, and 11.4% with major depression have not materially changed since a 2002 review based on 56 publications of mental illness. Reference Fazel and Danesh9

In contrast to one of our initial hypotheses, we did not find an increase in rates of psychosis and depression over time. The reasons for this are unclear but improvements in psychiatric care in prison, increased diversion of mentally disordered offenders from prison to hospital, and better living conditions may have contributed. Reference Skeem, Manchak and Peterson120 The role of international organisations, over the past two decades, in improving prison health has also been suggested to have a played a part. Reference Fraser, Møller and van den Bergh121

TABLE 2 Meta-regression analyses of sources of heterogeneity in the prevalence of psychosis and major depression in prisoners

| Psychosis | Major depression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable and study characteristicFootnote a | x03B2; | s.e.(x03B2;) | P | x03B2; | s.e.(x03B2;) | P |

| Gender of inmates: male v. female | 0.0016 | 0.063 | 0.800 | 0.0323 | 0.0222 | 0.151 |

| Mean age of inmates (continuous) | –0.0009 | 0.0009 | 0.334 | 0.0011 | 0.0033 | 0.735 |

| Year of study (continuous) | <0.0001 | 0.0003 | 0.889 | 0.0015 | 0.0013 | 0.340 |

| Country | ||||||

| Low/middle v. high income | 0.0204 | 0.0095 | 0.035 | 0.1157 | 0.0318 | 0.001 |

| USA v. rest of the world | 0.0007 | 0.0060 | 0.902 | –0.0043 | 0.0241 | 0.859 |

| Within the USA, over time | –0.0006 | 0.0005 | 0.241 | 0.0038 | 0.0013 | 0.008 |

| Prisoner status: sentenced prisoners v. detainees | 0.0025 | 0.0038 | 0.504 | 0.0136 | 0.0159 | 0.396 |

| On reception: first 2 weeks of reception v. rest | –0.0016 | 0.0058 | 0.778 | –0.0131 | 0.0241 | 0.588 |

| Participation rate | ||||||

| Continuous | –0.0184 | 0.0333 | 0.585 | –0.0778 | 0.0998 | 0.441 |

| Low (⩽80%) v. high (>80%) | –2.637 | 3.0964 | 0.400 | –0.2786 | 1.1458 | 0.809 |

| Sample size | ||||||

| Continuous | <0.0001 | 0.0000 | 0.337 | <0.0001 | 0.0000 | 0.577 |

| ⩽500 v. >500 | 0.0088 | 0.0062 | 0.156 | –0.0147 | 0.0275 | 0.594 |

| Interviewer: psychiatrist v. other | –0.0015 | 0.0053 | 0.784 | 0.0199 | 0.0231 | 0.391 |

| Diagnostic criteria: ICD v. DSM | –0.0021 | 0.0055 | 0.706 | –0.0590 | 0.025 | 0.021 |

Significant associations (P<0.05) are in bold.

a. For comparisons the reference category is given first.

Implications

Three main implications arise from these findings. First, the substantial burden of treatable psychiatric morbidity is confirmed by these findings. One in seven prisoners has depression or psychosis, and treatment may confer additional benefits such as reducing the risks of suicide Reference Fazel, Cartwright, Norman-Nott and Hawton3 and self-harm Reference Lohner and Konrad122 within custody, and suicide Reference Pratt, Appleby, Piper, Webb and Shaw123,Reference Bird124 and drug-related deaths on release Reference Kariminia, Law, Butler, Corben, Levy and Kaldor4 as well as reoffending. Reference Fazel and Yu5,Reference Baillargeon, Binswanger, Penn, Williams and Murray6 As reoffending rates are high (at 50% in the USA and UK within 2 years of release), 125,Reference Langan and Lewin126 treatment of prisoners may have a potentially large impact on public safety. In this context, the lack of good-quality treatment evidence remains concerning. Reference Fazel and Baillargeon127 The role of diversion away from prison at early stages of the criminal process and other collaborations between mental health and the justice system is underscored by our findings, Reference Steadman, Osher, Robbins, Case and Samuels18,Reference Morrissey, Fagan and Cocozza128,Reference Hassan, Birmingham, Harty, Jones, King and Lathlean129 particularly as repeat incarcerations are associated with mental illness. Reference Baillargeon, Binswanger, Penn, Williams and Murray6

Second, the higher prevalence of psychosis in prisoners in low- and middle-income countries is notable as rates of imprisonment are increasing in more of these countries than in high-income ones, Reference Walmsley1 and possibly faster; also service provision is likely to be worse. Health services in such countries can potentially use the estimates reported in this review in developing prison medical services, particularly in countries where resources are unlikely to allow for local prevalence studies to be conducted. In poorer countries, the role of explicit mental health budgets in ongoing health programmes could be considered, particularly for marginalised populations such as prisoners. Reference Prince, Patel, Saxena, Maj, Maselko and Phillips130 Our report does not provide information on the causes of higher prisoner rates of psychosis in low- and middle-income nations but possibilities include fewer opportunities and services for diverting offenders to health services, a stronger relationship between mental illness and criminality, and different sociocultural factors that mean more mentally ill people end up in prison. Poorer legal representation for the mentally ill may be one such factor. The increased comorbidity with opioid use in prisoners found in some countries and that form part of the illegal drug trade may be another. Reference Assadi, Noroozian, Pakravannejad, Yahyazadeh, Aghayan and Shariat96

A final implication from this review is that, although internationally the prevalence of depression does not appear to be increasing in prisoners, in the USA, which has the largest prison population worldwide, the rate of depression appears to have been increasing over time. This was not found for psychosis in prisoners internationally or in the USA, which may be partly because the incidence of psychotic disorders has not increased in the general population either. Reference McGrath, Saha, Welham, El Saadi, MacCauley and Chant131 In relation to increased depression in US prisoners, further work could investigate the possible contributions of the closure of large psychiatric hospitals, the provision of community care, the funding of mental health and the reported increase in major depression rates in the general population. Reference Kessler, Berglund, Demler, Jin, Koretz and Merikangas132 Whatever the causes, the US houses more than three times more mentally ill people in prison than in all psychiatric hospitals, Reference Torrey, Kennard, Eslinger, Lamb and Pavle133 and undertreatment for mental illness in US prisons exacerbates these problems. Reference Wilper, Woolhandler, Boyd, McCormick, Bor and Himmelstein134 Simple measures, including having policies and guidelines for the transfer of severely mentally ill people to psychiatric hospitals, training of prison staff and discharge planning, may improve these rates. Reference Torrey, Kennard, Eslinger, Lamb and Pavle133

FIG. 3 Prevalence of psychotic illness in prisoners over time in (a) individual studies from all countries (including the USA) and (b) studies conducted in the USA only.

The size of the circles is proportional to the sample size of each study.

FIG. 4 Meta-analysis of the prevalence of major depression in prisoners by country group (low–middle income v. high income).

Weights are from random-effects analysis. Smaller studies: n<250. ES, prevalence. a. On early reception.

Strengths and limitations

The high levels of heterogeneity between the studies are to be expected as the studies were conducted by different groups in a large variety of prisons using differing methods, Reference Higgins135 and this may simply reflect real differences in prevalences over time and by region. This may also be an explanation for the asymmetric funnel plots we reported in addition to possible publication bias. Reference Egger, Smith, Schneider and Minder38 Also, publication bias may explain the small number of studies in low- and middle-income countries, and such bias is thought to contribute in all mental health research from these countries. Reference Singh136 Our approach to this was to identify causes of heterogeneity, and two possible explanations were found. In depression, we found that studies using DSM criteria had higher rates than those using ICD criteria. Although such differences have occasionally been found in community studies, and a lower congruence between the two diagnostic systems for depression diagnoses compared with some other psychiatric disorders has also been reported, Reference Cheniaux, Landeira-Fernandez and Versiani137 particular reasons for this difference in prisoners are unclear. Possibilities include that in the diagnostic systems, fatigability is included in the core criteria for depression in ICD, but it is an associated (rather than a core) feature in DSM. In addition, it may be that the distinction between melancholic and non-melancholic forms of depression Reference Parker138 is more important in prisoners as the overlap between sadness and clinical depression is more difficult to determine.

FIG. 5 Prevalence of major depression in prisoners over time in (a) individual studies from all countries (including the USA) and (b) studies conducted in the USA only.

The size of the circles is proportional to the sample size of each study.

The strengths of this review include the large number of samples and prisoners included, and therefore the ability to examine prevalences by clinically relevant subgroups with some degree of precision. However, we identified only eight studies in low- and middle-income countries, and our findings should be interpreted with caution. Furthermore, we have examined heterogeneity using subgroup analyses and meta-regression, which allowed us to investigate dichotomous and continuous variables such as age, sample size and the date when the study was conducted. One of the limitations of the review is that there may be other explanations for the heterogeneity that we did not test, such as comorbidity with other mental disorders, but systematic data on this were lacking. Furthermore, the statistical power of testing trends within nations was limited, and even our findings on US trends were based on 17 studies.

Avenues for future research

A number of research implications arise from this review. First, studying the epidemiology of mental illness and criminality in low- and middle-income countries and how it compares with high-income countries may provide some reasons for the difference in psychosis prevalence. A recent review found no such studies in low- and middle-income countries. Reference Fazel, Gulati, Linsell, Geddes and Grann139 More research into the treatment of mentally ill prisoners and the most effective models of service delivery is pressing, and further comparison of novel approaches needs closer examination. Reference Raimer and Stobo140 Future prison surveys should include information on comorbidity and psychiatric history, suicide attempts within custody, treatment received in prison and adherence to treatment, and length of custody. In addition, the relationship between mental illness in prisoners and recidivism rates needs further examination.

In summary, prison provides a unique public health opportunity to treat mental illnesses that otherwise may not be treated in the community. Almost all prisoners return to their communities of origin, and effective treatment of mentally ill prisoners will have potentially substantial public health benefits and possibly reduce reoffending rates.

Funding

K.S. was funded by the German Friedrich-Ebert Stiftung.

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Agbahowe, H. Andersen, L. Birmingham, R. Bland, G. Cote, M. Davidson, B. Denton, R. Ghubash, J. Haapsalo, H. Herrman, W. Hurley, K. Jordan, M. Joukamaa, T. Maden, D. Mohan, B. Morentin, W. Narrow, K. Northrup, T. Powell, K. Rasmussen, C. Schoemaker, N. Singleton, C. Smith and G. Walters for kindly providing additional data from their studies for the initial review. We are grateful to T. Butler, B. Falissard, H. Kennedy, M. Pereira Pondé, M. Piselli and R. Quartesan, C. E. von Schoenfeld, R. Trestman and V. Tort for providing further information about their studies for the update. In addition, K. Abram, D. Black, C. James, O. Nielssen, M. I. da Rosa and K. Wada helpfully responded to queries. We are grateful to J. Baillargeon for comments on a previous draft. Kat Witt assisted as the second data extractor.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.