The attitude to treating psychosis has recently changed from simply focusing on severe enduring mental illness to also including early intervention. Reference Garety and Jolley1 Treating psychotic disorders in their earliest stages has become a focus for research and clinical care. Reference Yung and McGorry2 New terms appeared including: first-episode psychosis; duration of untreated psychosis (DUP; from onset of positive psychotic symptoms until starting treatment); and duration of untreated illness (from onset of prodrome until starting treatment). Reference Compton and Esterberg3 First-episode psychosis studies show that the average time between onset of symptoms and first effective treatment is often 1 year or more. Reference McGlashan4 Long DUP is undesirable for various reasons.

-

1. Early treatment helps minimise the risk of serious consequences as a result of changes in mental state and behaviour. Reference Larsen and Johannsen5,Reference Wyatt, Damiani and Henter6

-

2. Shorter DUP is associated with better clinical response. Reference Perkins, Lieberman, Hongbin, Tohen, McEvoy and Green7

-

3. Early treatment can reduce suffering. Reference Ho, Alicata, Ward, Moser, O'Leary and Arndt8

-

4. Early results suggested that an early intervention in psychosis service is more cost-effective than generic services. Reference Mihalopoulos, McGorry and Carter9

Plans have been put in place to develop a network of early intervention in psychosis services across the UK. 10

Most general practitioners (GPs) see one to two new people with first-episode psychosis a year. Reference Shiers and Lester11 This small figure may lead to underestimating the importance of the primary care role of early intervention in psychosis. However, Shiers & Lester believe that early intervention in psychosis needs greater involvement of primary care for its success. Reference Shiers and Lester11 Our study examined the local primary care experience of first-episode psychosis before developing the local early intervention in psychosis service.

Method

We undertook a cross-sectional survey of GPs using a colour-coded confidential questionnaire of eight questions requiring ticks to multiple-choice options and free text comments. The questionnaire was developed by M.E.-A., reviewed and approved by a panel of ten clinicians including five psychiatrists, three community psychiatric nurses, one mental health social worker and one GP with an interest in mental health. The questionnaire focused on GP's experiences with individuals with first-episode psychosis regarding referral trends, prescribing medication, engaging in treatment, preferred model of service and causes of delayed referral to the psychiatric service. The clinical governance support team sent the questionnaires to all Northamptonshire GPs in 2004, with a covering letter highlighting the importance of their contribution, as it would influence the local early intervention in psychosis model, and requested their response within 3 weeks. Non-responders were not followed-up. Data collection and analysis was carried out by the clinical governance support team.

Northamptonshire is in the eastern part of central England with an area of 2364 km2 and a population of 646 600 (mid-2003 estimate) including: 95.1% White, 2% South Asian, 1.2% Black African and Caribbean, and 1.8% from other ethnic minority groups. Population density is 272/km2. Northamptonshire is largely rural and Northampton is the largest town with a population of 194122.

Results

Out of 284 GPs, 123 (43%) responded. The response rate varied between 27% and 53% across the eleven catchments areas. Fifteen (7%) GPs requested a copy of the final report.

Starting treatment

Sixty-three GPs (51% of responders) start treatment in 10% or less of individuals with first-episode psychosis before referring them to the psychiatric service and eleven GPs (9% of responders) start treatment in 25% of individuals. Nineteen GPs (15.5% of responders) start treatment in 50% of people with first-episode psychosis and nineteen GPs (15.5%) start treatment in 75% or more of people before referring to the psychiatric service. Eight GPs (7%) were unsure and three GPs (2%) did not answer.

GP referral trends

Five GPs (4% of responders) do not refer individuals with first-episode psychosis to the psychiatric service until the clinical picture is clear. Two GPs (2%) only refer those who request a referral, whereas nine GPs (7%) refer those who accept referral. Forty-two GPs (34%) refer those who request or accept being referred. Sixty-six GPs (53%) refer all people with first-episode psychosis even if they refuse being referred.

Individuals’ attitude towards referral

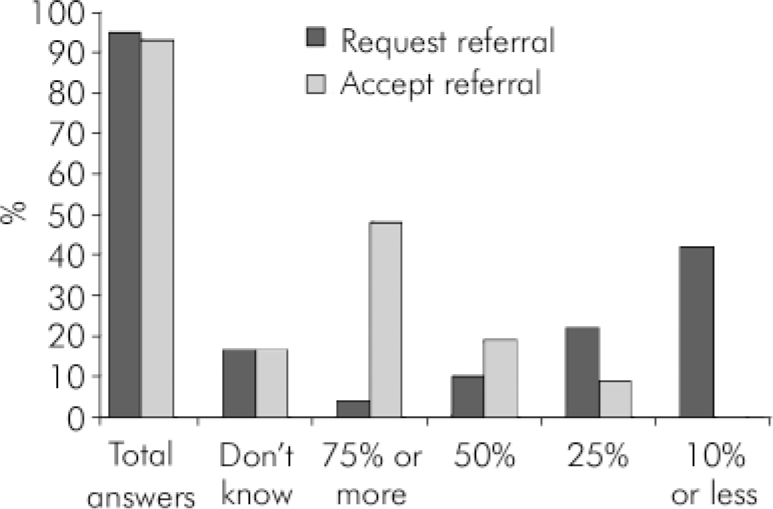

Twenty-one GPs (17%) did not know the proportion of people with first-episode psychosis that request or accept referral to a psychiatric service (Fig. 1). Five GPs (4%) believed that 75% of individuals with first-episode psychosis ask for referral, 11 GPs (10%) believed that 50% ask and 51 GPs (42%) believed that only 10% or less ask. If people with first-episode psychosis are offered a referral, 58 GPs (48%) believed that 75% or more would accept, 23 GPs (19%) believed that 50% would accept and 11 GPs (9%) believed that only 25% would accept.

Engaging with treatment

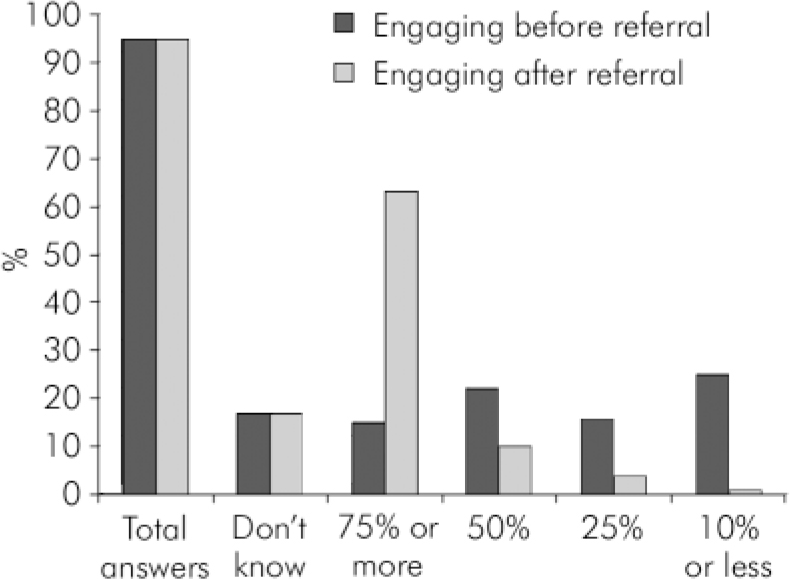

In total, 116 GPs (95%) answered this question and 7 GPs (5%) did not (Fig. 2). Twenty-one GPs (17%) responded with ‘don't know’ about first-episode psychosis engagement before or after referral. Eighteen GPs (15%) believed that 75% engage before referral, whereas 77 GPs (63%) believed that 75% engage after referral. Twenty-seven GPs (22%) believed that 50% are likely to engage before referral and twelve GPs (10%) believed that 50% are likely to engage after referral. Nineteen GPs (16%) believed that 25% are likely to engage before referral and five GPs (4%) believed that 25% engage after referral. Thirty-one GPs (25%) believed that 10% or less are likely to engage before referral and one GP (1%) believed that 10% or less engage after referral.

Fig. 1. General practitioner experience of first-episode psychosis: attitudes towards referral to psychiatric services.

Fig. 2. First-episode psychosis: engaging before and after referral.

Number of individuals with first-episode psychosis

We asked the GPs how many individuals with first-episode psychosis they had seen in the past 12 months. Overall, 121 GPs (98%) answered and 2 GPs (2%) did not; 84 GPs (68%), saw one to two people with first-episode psychosis, 16 GPs (13%) saw three to five, 3 GPs (2%) saw five or more and 18 GPs (15%) did not see any.

Is there a need for an early intervention in psychosis service?

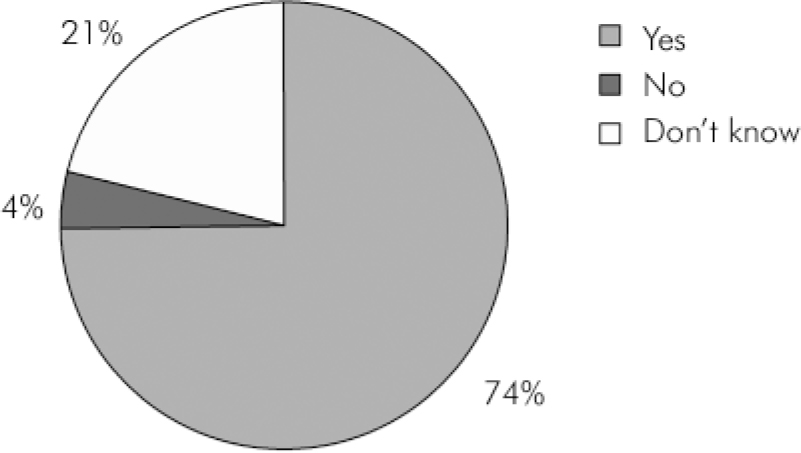

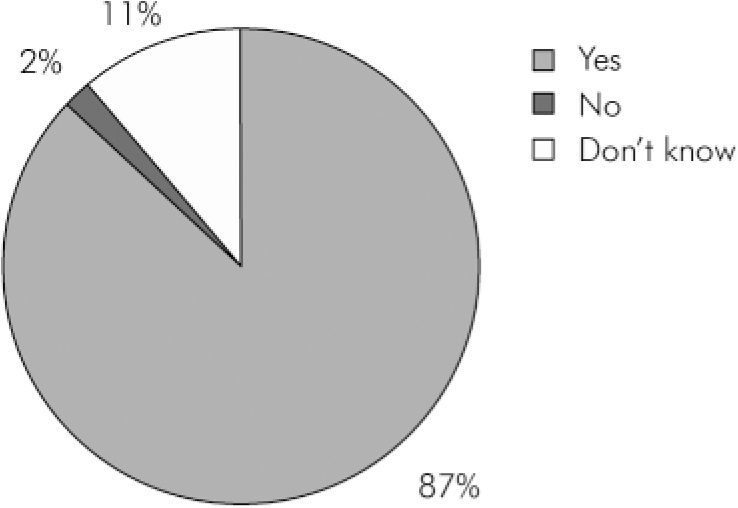

Overall, 5 GPs (4%) did not feel the need for an early intervention in psychosis service, 26 GPs (21%) did not know and 92 GPs (74%) agreed that an early intervention in psychosis service is needed (Fig. 3). If there was an early intervention in psychosis service, 3 GPs (2%) would not use it, 13 GPs (11%) did not know and 107 GPs (87%) would use it (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3. Is there a need for an early intervention in psychosis service?

Fig. 4. Would you use an early intervention in psychosis service?

Preferred service model

A total of 119 GPs (97%) answered and 4 GPs (3%) did not answer. Seventy-seven GPs (63%) welcome having a mental health clinic in their surgeries with 37 GPs (30%) preferring a mental health clinic run by a clinician from the mental health service, 12 GPs (10%) preferring a clinic run jointly by the GP and a mental health clinician and 28 GPs (23%) accepting either. However, 21 GPs (17%) refused having a mental health clinic in their surgery and 21 GPs (17%) had other views including: no need to slice an already overstretched service to give it a new name with another waiting list; GPs wish to have an open access to psychiatric out-patient slots; and urgent home visits at GP request are more important.

Causes of delayed referral identified by GPs

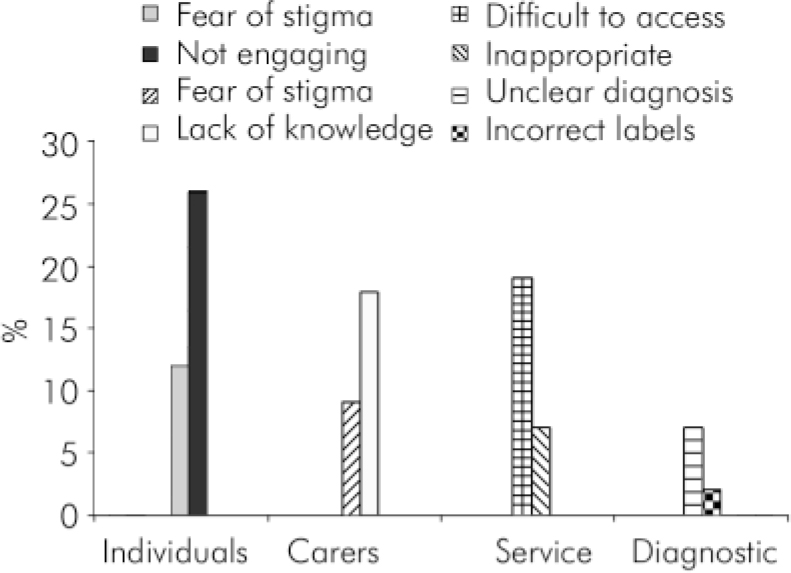

These include the following (Fig. 5):

-

• fear of stigma by individuals (43 GPs, 12%)

-

• individuals not engaging (96 GPs, 26%)

-

• carers’ fear of stigma (33 GPs, 9%)

-

• carers’ lack of knowledge about mental illness (66 GPs, 18%)

-

• service difficult to access (69 GPs, 19%)

-

• inappropriate service (26 GPs, 7%)

-

• unclear diagnosis (25 GPs, 7%)

-

• psychiatrists incorrectly label individuals (8 GPs, 2%).

Discussion

This is the first UK primary care survey that studied GPs’ experiences of first-episode psychosis with a relatively good overall response rate compared with similar studies (e.g. a postal survey in 1995-6 of GPs in the Midlands produced an initial response rate of 32%). Reference McAvoy and Kaner12 This may reflect the growing importance of mental health in primary care.

Fig. 5. General practitioners’ experience of the main causes for delayed referral of people with first-episode psychosis to a psychiatric service.

GPs’ prescribing and referral trends

Study results show wide variation in GPs’ experiences with first-episode psychosis. General practitioners are likely not to start treatment in first-episode psychosis before referring to a specialist service with variations in prescribing trends that may reflect differences in GPs’ training, experience and interest.

General practitioners’ tendency to only refer individuals with first-episode psychosis when the diagnosis is clear or those who request and/or accept referral may lead to delayed access to specialist care. Later, many of those individuals will settle into a relapsing pattern, present in emergency situations to be dealt with by psychiatric services in a fire-fighting manner exhausting healthcare resources. Reference Birchwood, Fowler and Jackson13 Referring all individuals with first-episode psychosis even if they refuse is likely to be associated with a high rate of ‘did not attend’. Thus, early intervention in psychosis services need to facilitate access to care and GPs need to be more proactive with a higher index of suspicion and a lower referral threshold. This would agree with the findings of Edwards & McGorry who stated that GPs have a potentially important role in early recognition and referral of first-episode psychosis. Reference Edwards and McGorry14

Main causes for delayed referral

Interestingly, GPs identified individuals disengaging, services being difficult to access or inappropriate, stigma, carers’ lack of knowledge about mental illness and unclear diagnosis as the most important reasons for delayed referral of people with first-episode psychosis. Lincoln & McGorry identified similar factors in tackling delayed access to services in first-episode psychosis including stigma, clinical features, gender and inaccessible services. Reference Lincoln, McGorry, McGorry and Jackson15

Most GPs see one to two new people with first-episode psychosis a year which agrees with that indicated by Shiers & Lester. Reference Shiers and Lester11 Some GPs reported figures of two or more new cases a year probably because of higher levels of morbidity and high turnover in their catchment area (e.g. Maple Centre for homeless individuals). In most industrial countries the incidence of new cases of schizophrenia is 15/100 000 a year. Reference Johnstone, Johnstone, Freeman and Zealy16 Northamptonshire's population is 650 000 (www.northampton.gov.uk/site/scripts/documents_info.php?documentID=171&pageNumber=2), i.e. about 100 new cases of schizophrenia are expected a year locally. Some may argue whether this number is big enough to require a new specialist service. However, early intervention in psychosis services will deal with all forms of early psychosis (e.g. affective, drug induced) as well as those that may prove later not to be psychosis. Early intervention in psychosis services may have to see and follow-up a much larger number of individuals to identify cases of psychosis.

Some GPs may be inhibited from seeking specialist help for various reasons, for example a lack of knowledge about resources and how to access them, disillusionment with mental health services and a belief that individuals and families may be offended by recommending psychiatric help. Reference Lincoln, McGorry, McGorry and Jackson15 It is vital that early intervention in psychosis service developers consider this and address the underlying issues relevant to GPs and professionals in other services (e.g. teachers).

Novel approach and a partnership are needed

A major GP and public concern is waiting lists and times. It is important that early intervention in psychosis services do not develop long waiting lists/times and use a novel and less stigmatising approach, otherwise the whole concept will lose its meaning (i.e. ‘early intervention’).

Early intervention in psychosis requires a partnership of primary and secondary care and wider involvement of the community to make a difference. Reference Shiers and Lester11 Early results from Early Treatment and Identification of Psychosis (TIPS) in Norway and Denmark suggest that public education and specific education for teachers, youth workers and GPs about first-episode psychosis can assist early detection and reduce DUP. Reference Shiers and Lester11,Reference Larsen, McGlashan, Johannessen, Friis, Guldberg and Haahr17 An early intervention in psychosis service model that suits an inner-city area of a big city such as London may not suit a small town or its surrounding rural areas. Therefore the local model has to be flexible and needs based. Reference Singh, Wright, Burns, Joyce and Barnes18

Questionnaire surveys of clinical practice do not necessarily provide an accurate picture of clinical process and activity. Care professionals completing the questionnaires might feel that their services are being scrutinised and provide ‘acceptable answers’. Reference Singh, Wright, Burns, Joyce and Barnes18 This study questionnaire was confidential and focused on GPs experience, views and expectations. This is likely to help avoid or at least minimise such a tendency.

Conclusion

General practitioners’ experience with first-episode psychosis indicates that people are more likely to accept referral to a psychiatric service if offered it than to ask for it. The likely causes for delayed referral of people with first-episode psychosis to a psychiatric service are: individuals disengaging, stigma, service being difficult to access or inappropriate, carers’ lacking knowledge about mental illness and GPs waiting to make a diagnosis. General practitioners need to be adequately informed about early intervention in psychosis and the importance of their role for its success.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.