Women’s candidacies for Congress and state legislatures hit record highs in 2018 and again in 2020 (CAWP 2020). Given the low number of women in public office, this growth is a positive development for American democracy. Yet on many dimensions, including class, race, age, income, education, and parenthood status, women candidates are still far from representative of women as a whole (Brown and Dowe Reference Brown, Dowe, Shames, Bernhard, Holman and Teele2020; Carroll and Sanbonmatsu Reference Carroll and Sanbonmatsu2013; Shah, Scott, and Juenke Reference Shah, Scott and Juenke2019). The low number of women officeholders in general, and of disadvantaged women in particular, decreases both descriptive and substantive representation (Barnes and Holman Reference Barnes and Holman2019; Brulé Reference Brulé2020; Ladam, Harden, and Windett Reference Ladam, Harden and Windett2018; Mansbridge Reference Mansbridge1999) and reduces public trust in government (Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019). Individual women’s decisions to seek office, while highly personal, have important consequences for public life. What are the factors that drive some women and not others to emerge onto the political stage?

Earlier scholarship emphasized how women’s domestic responsibilities shaped the contours of their public lives by imposing high costs on political participation (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001; Iversen and Rosenbluth Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2006; Sapiro Reference Sapiro1982). However, most recent research has converged on women’s relative lack of political ambition as the primary driver of women’s underrepresentation, at least in the United States (Piscopo Reference Piscopo2019).Footnote 1 Key texts on women’s ambition find that household composition, including marital status and motherhood, does not alter women’s political ambition in a meaningful way (Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2014). Yet, if family dynamics do not influence women’s political ambition, why are single women, mothers, and especially single mothers, so much less likely to seek and hold political office in the US?

In this paper, we revive the debate about family lives and political ambition, arguing that even for the most politically engaged and ambitious women, motherhood and income-earning responsibilities may suppress candidate emergence. In advancing this claim, we make theoretical, methodological, and empirical contributions to our understanding of political ambition. First, we decouple two types of political ambition, arguing that the factors that contribute to “nascent ambition”—a professed desire to hold office—differ from those that contribute to “expressive ambition”—actually competing in an election (Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2005). Individual-level nascent ambition does not determine who runs; instead, nascent ambition produces expressive ambition within a set of structural barriers that vary by household.

Specifically, we hypothesize that three factors—two related to resources, one to household composition—affect even the most ambitious women as they decide whether to run. We should observe an income constraint if lower household income prevents poorer women from investing time in political service. We should observe a breadwinner constraint if responsibility for the lion’s share of income reduces women’s tendency to run for office, either separately or in combination with household income. Finally, we expect income and breadwinning to interact with household composition: women who do not have support from other earners, and those with dependents, may be least likely to run.Footnote 2 Taken together, this suggests that the political economy of the household keeps many of the most ambitious women from emerging as candidates.

Methodologically, this paper addresses a central challenge for research on candidate emergence: how to identify the correct “pool” of individuals to study. Because of self-selection, studies of individuals who have already filed for candidacy cannot provide insight into the factors that prevent people from ever seeking office.Footnote 3 Scholars have therefore sought to determine who is in the likely candidate pool by focusing on elites (Holman and Schneider Reference Holman and Schneider2018; Lawless and Fox Reference Lawless and Fox2005; Shames Reference Shames2017; Sidorsky Reference Sidorsky2019). Yet as Thomsen and King (Reference Thomsen and King2020) persuasively demonstrate, even among elites, conversion to candidacy is rare. The result is that many studies lack either the statistical power or enough individual-level information to unpack the influence of family life on candidate emergence.

We overcome this empirical challenge through a multimethod study of women who offer the “best bet” of emerging as candidates: alumnae of the selective, intensive, Democratic women’s campaign training program, Emerge America. Although there are women officeholders in the Republican Party, the vast majority of women who run for and achieve elective office in the United States hew Democratic.Footnote 4 Emerge is a major institution in the latter space: graduates of the program alone constituted 9% of the 3,418 women who ran for state legislative office in 2018, and 50% of Emerge trainees do run for office. This sample thus offers new insight into the factors that help the largest group of women with high nascent political ambition express their ambition. We use multiple types of data from program applicants and alumnae between 2003 and 2016, including screening and interview data, intake information, and an original national survey, to demonstrate that the intrahousehold allocation of financial responsibilities and motherhood suppress late-stage candidate emergence among Democratic women who are likely candidates.

Two findings stand out. First, we present new qualitative and quantitative evidence consistent with a “breadwinner” constraint: breadwinners were between 13 and 16 percentage points less likely to run for office than were nonbreadwinners. To put this into perspective, our most conservative estimate of the breadwinner effect is more than double the size of the 6-point gender gap in expressive ambition identified by Fox and Lawless (Reference Fox and Lawless2004). Second, breadwinner effects operate differently for women depending on household composition. Mothers who were partnered (cohabitating or married) and not earning separate income had the highest rates of candidacy (60% ran), while partnered breadwinners with children and unpartnered women were the least likely to throw their hats into the ring (38% and 32%, respectively). These findings help explain why many ambitious women fail to emerge even when recruited, and why single mothers, typically their households’ main earners, are rarely found in Congress (Gibson Reference Gibson2019).

The last section of the paper considers the internal validity and generalizability of these findings. We find that Emerge did not select breadwinners that were disadvantaged on other dimensions relative to women without earning responsibilities, and that individual sorting into more or less costly campaigns cannot explain the results. We further discuss whether the same constraints are likely to operate for Republican women or for men. Finally, in investigating the lack of an income effect, we find that despite providing financial aid, the program inadvertently selects on income during the admissions process; thus, as for the working class, low income may prevent serious consideration and recruitment to candidacy (Box-Steffensmeier Reference Box-Steffensmeier1996; Carnes Reference Carnes2015; Reference Carnes2016). We conclude by considering the policy implications and potential interventions that might increase the representation of less-privileged women in public life.

Political Ambition and Candidate Emergence

The concept of political ambition has an impressive scholarly pedigree. In the mid-1960s, researchers began to theorize political ambition as it related to opportunities to become politically engaged.Footnote 5 In early scholarship, ambition was not “free floating” but situational (Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger1966), based on rational decision making about the costs and benefits of holding office and the likelihood of winning given the political environment (Black Reference Black1972, 145). The next wave of scholarship formalized models of ambition and began identifying its levels, effects, constraints, and exceptions.Footnote 6 This work maintained a focus on context, especially the structural and institutional realities that shaped the probability of victory, but tempered this “opportunity structure” view with an understanding that aspirational goals could enhance or suppress individual political ambition.Footnote 7

The archetypical candidate in pioneering ambition studies was undoubtedly white and male, but in the 1980s gender scholars turned to ambition as a potential cause of women’s underrepresentation (Rule Reference Rule1981). As Sapiro (Reference Sapiro1982) noted, because women faced different demands on their time due to the gendered division of household labor, their ambitions were structurally constrained.Footnote 8 An early-1990s surge of women candidates, especially during the press-dubbed “year of the woman” in 1992, galvanized the gender and politics subfield.Footnote 9 While research in the 1990s and 2000s debated whether structural constraints—women’s greater household responsibilities and lower income and wealth—still constituted barriers to women’s participation (e.g., Schlozman, Burns, and Verba Reference Schlozman, Burns and Verba1994), new theories of ambition put the focus back on individual psychology.Footnote 10 These theories suggested that gender differences in ambition resulted from differences in socialized personality traits or perceptions of campaigning.Footnote 11 Such studies suggested that low ambition might be overcome via encouragement and recruitment, including through candidate training programs.Footnote 12

In recent years, prominent studies of gender and ambition have discounted the role of the household. Through an analysis of women in prestigious careers, Fox and Lawless (Reference Fox and Lawless2014) conclude “traditional family dynamics do not account for the gender gap in political ambition. Neither marital and parental status, nor the division of labor pertaining to household tasks and child care, predicts potential candidates’ [nascent] political ambition” (399; brackets ours). Yet even if this is true, it cannot explain why the household composition of women who actually hold elected office differs so greatly from both that of male politicians (Carroll and Sanbonmatsu Reference Carroll and Sanbonmatsu2013, Table 2.5) and from women in the general population (Teele, Kalla, and Rosenbluth Reference Teele, Kalla and Rosenbluth2018, 534).

Decoupling the concepts of nascent and expressive ambition helps reconcile these apparent contradictions. Nascent political ambition—“the inclination to consider a candidacy”—and expressive political ambition—“the [choice] to enter specific political contests” (Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2005, 644) may be subject to different dynamics. Separating these two concepts raises the question of how one converts into the other, thereby highlighting the gap between them. Nascent ambition is by definition abstract and aspirational. Whether in the general population or among elites, women who are married, mothers, or breadwinners may voice just as much nascent ambition as women who are free from those constraints. But to increase women’s representation, nascent ambition is not enough; more women actually need to become candidates (Thomsen and King Reference Thomsen and King2020). For well-resourced, ambitious women, turning on the pipeline’s tap through recruitment and encouragement may be enough to tip the balance in favor of candidacy. But for many others with nascent ambition, household demands may constrain their ability to express their ambition through candidacy.

The Political Economy of Ambition

The political economy of the household is the key to bridging the gap between women’s nascent and expressive political ambition. Scholarship has long suggested a link between socioeconomic resources and political participation (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba1997; Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001; Carnes Reference Carnes2016; Schlozman, Burns, and Verba Reference Schlozman, Burns and Verba1994; Reference Schlozman, Burns and Verba1999). Rising education and increased labor force participation by women were heralded as key ways to close gender gaps in politics (Rule Reference Rule1981; Sapiro Reference Sapiro1982), but research on gender and participation (e.g., Burns, Schlozman, and Verba Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba1997; Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001) and household bargaining and voting (e.g., Brulé Reference Brulé2020; Brulé and Gaikwad Reference Brulé and Gaikwad2021; Iversen and Rosenbluth Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2006; Prillaman Reference Prillamanforthcoming) suggests that the relationship between household resources and gender gaps in political participation persists despite this progress.

Building on this literature, we propose new theoretical mechanisms—not mutually exclusive—that link structural and resource factors to women’s decisions to emerge. Household income might influence the decision to run if, like normal goods in economics, women from wealthier backgrounds face lower barriers to political candidacy (Carnes Reference Carnes2016; Carnes and Lupu Reference Carnes and Lupu2016, 841). While there are obvious costs to campaigning for higher office, winning a lower-level public office—often unpaid or poorly paid—poses its own financial barriers. Such costs predict an income constraint, whereby women who command fewer financial resources will be less likely to run, while women in wealthier households will have greater freedom to invest in politics.

Yet the absolute size of household income might have less of an influence on candidate emergence than who produces it. If women are responsible for the majority of their household’s income, because of either household composition or career choices, they may not be able to emerge as candidates for fear of losing household stability (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba1997; Norris and Lovenduski Reference Norris and Lovenduski1995). In America today, most women participate in the labor force for the majority of their adult lives (Ruggles Reference Ruggles2015). But because women rarely bring in more than half of the entire household’s income in dual-earner heterosexual households (Bertrand, Kamenica, and Pan Reference Bertrand, Kamenica and Pan2015; Lyttelton, Zang, and Musick Reference Lyttelton, Zang and Musick2020), they may have less power to bargain for free time. These time constraints are exacerbated by gender norms surrounding housework: a substantial body of literature attests that even when women are breadwinners, they still undertake more housework than do men.Footnote 13 And this may be doubly true for women of color, who experience even more acute “second shift” demands (Holman and Schneider Reference Holman and Schneider2018; Stokes-Brown and Dolan Reference Stokes-Brown and Dolan2010). We hypothesize that a breadwinner constraint would operate if women who are breadwinners, regardless of overall income, have lower levels of candidacy than women who are not breadwinners.

Finally, we expect these constraints also depend on household composition. A growing body of research shows that household structure affects the allocation of responsibilities and resource access within families (Brulé and Gaikwad Reference Brulé and Gaikwad2021; Khan Reference Khan2019; Prillaman Reference Prillamanforthcoming), with motherhood emerging as a crucial determinant of women’s political agency (Deason, Greenlee, and Langner Reference Deason, Greenlee and Langner2015). In addition, women head more than 80% of single-earner households (Houston Reference Houston2013), a position that leaves little leeway for extracurricular pursuits. We hypothesize that women who are not partnered with a second income earner, or who have additional financial dependents like children, may rationally focus on breadwinning or caregiving rather than pursuing politics. We therefore expect household structure will interact with income and breadwinning to constrain women’s candidacies. Single mothers, who may have lower income or more intensive breadwinning or caregiving responsibilities than do other potential candidates, should be least likely to convert nascent ambition into candidacy.

Studying Expressive Ambition

Decoupling nascent and expressive ambition enables us to bring household political economy back into the literature on women’s political ambition. Yet empirically disentangling the two concepts requires that scholars overcome a formidable methodological challenge: identifying the right “pool” of potential candidates to study.

Prior work often analyzed elected officials (Carroll and Sanbonmatsu Reference Carroll and Sanbonmatsu2013; Fowler and McClure Reference Fowler and McClure1989; Fulton et al. Reference Fulton, Maestas, Maisel and Stone2006), but such studies cannot tell us why those who never emerge as candidates fail to do so. Yet systematically identifying plausible candidates who have not yet made the decision to run is hard. Scholars have therefore sought to determine who seems most likely to run, often by focusing on political elites. Recent work examines candidate emergence among women with four-year degrees (Holman and Schneider Reference Holman and Schneider2018), graduate students at prestigious universities (Shames Reference Shames2017), those in high-powered legal or business careers (Lawless and Fox Reference Lawless and Fox2005), political activists (Fox and Lawless Reference Fox and Lawless2004), women of color in state races (Shah, Scott, and Juenke Reference Shah, Scott and Juenke2019), and local office-holders (Crowder-Meyer Reference Crowder-Meyer2018; Sidorsky Reference Sidorsky2019). Thomsen and King’s (Reference Thomsen and King2020) cutting-edge research, which reinforces the finding that the rate of candidate emergence even among elites is low, does not have detailed data on the characteristics of candidates and their households.Footnote 14 Accordingly, they too cannot provide enough traction on the factors that move candidates from nascent to expressive ambition.

We argue that studying “political novices”—a group of women with high nascent political ambition undergoing candidate training but who have not yet advanced to candidacy—provides the greatest insight into the factors that inhibit women with nascent political ambition from expressing their ambition.Footnote 15 These novices are provided with high levels of encouragement and political resources, allowing us to rule out many existing explanations for women’s lower ambition. They are therefore the ideal sample with which to test the relationship between the political economy of the household and candidate emergence.

Data and Design

Emerge America, first established as Emerge California in 2002, is a well-known national organization that trains Democratic women to run for office. With chapters now in 25 states, 813 candidates standing for office in 2018, and over 670 candidates running in November 2020, it is the largest, most comprehensive, and most visible program of its kind (Emerge America 2018). Aimed at “building the farm team” for the Democratic Party by encouraging highly skilled women to run for state and local offices,Footnote 16 Emerge provides comprehensive training, including public speaking, fundraising, field operations, messaging, and ethics. Trainees network with graduates already in elected office as well as political consultants and potential endorsers. Once alumnae decide to run, Emerge provides pro bono advisory teams to guide candidates through hiring and establishing campaign organizations.

The program is both selective and intensive. Applicants submit a packet that includes their professional and political experience and an essay describing their goals for candidacy, including pinpointing the office they hope to attain. Each application is rigorously evaluated by initial readers, interviewers, and finally the Emerge board.Footnote 17 Program fees vary by state and over time, but in the last year for which we have data for California, the costs were about $1,000. In that year, over a quarter of enrollees received financial aid covering about half of total program costs.

Emerge offers more comprehensive trainings, networking, and political resources than competitors. Each state’s program requires at least 70 hours of trainings led by national and local political experts; few with a passing interest in politics would take on such a commitment. Emerge graduates thus seem to have both the resources and the will to run. Yet even here, in a “most likely” case, 50% of the program’s alumnae do not run. What explains this variation?

We began our study of the decision to run with participant observation of training sessions in the Emerge California chapter (the largest state affiliate) between 2014 and 2016. To this we added formal interviews of leading national office staff and state executive directors. From these conversations, we compiled survey questions and acquired several sources of data on the women who pass through Emerge including the following: (1) intake data: initial demographic characteristics of all Emerge America’s graduates, which we use to assess representativeness of respondents to our alumnae survey; (2) applicant screening data: full records of screening interviews for more than 200 applicants to Emerge California from 2008 to 2012 and application files from 2002 to 2012, which we use to understand program selection, and for applicants who did not participate in the program, we also collected information on whether they eventually ran for office;Footnote 18 and (3) our alumnae survey: an original national survey of Emerge America alumnae who graduated between 2003 and 2016.

Sampling Frame and Survey Recruitment

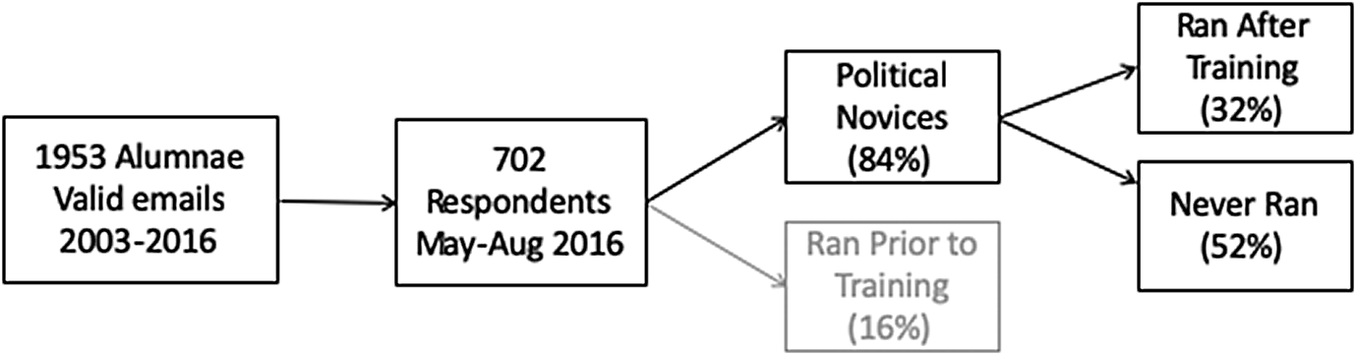

From 2003 to 2016, across all state branches, Emerge ushered 2,083 women through its program. This roster produced a list of 1,953 alumnae with valid email addresses. Using this database, we recruited Emerge alumnae from all 16 state affiliates that existed in 2015 to participate in our Qualtrics survey from May to August 2016. In total, 702 women answered the survey,Footnote 19 generating a final response rate of 37% of those with valid contact information, or 35% of all alumnae (Figure 1).Footnote 20

Figure 1. Study Group, Sample, and the Dependent Variable—the Decision to Run among Political Novices

Note: The percentages listed refer to the share in each category of total respondents. Overall, the 32% of total respondents that ran after the training represents 39% of all novices.

We assess the representativeness of our respondent sample by comparing the difference of means between alumnae who took the survey and those who did not using social, economic, and demographic information measures from Emerge’s national intake data (full results in Appendix A-3). Respondents match the Emerge alumnae population on age, sexual orientation, and parenthood status. Geographically, the sample is nationally diverse, with larger populations in states with more graduates. White alumnae were slightly more likely to respond (65% versus 61% of alumnae), as were more recent alumnae. Otherwise, our sample seems representative of Emerge’s alumnae.

Survey Design and Analysis

Our 15-minute survey was designed to gather data related to several branches of the women’s emergence literature including resource and demographic factors (e.g., income, race, and geographic location), perceptions of and responsiveness to political and institutional constraints (e.g., local party support and open seats), and motivations and fears about running for office (e.g., concerns about loss of privacy, discrimination, and competition).Footnote 21

Dependent Variable

Our primary dependent variable is the decision to run among political novices—those who had not run for office prior to Emerge training. In practice, respondents fall into three categories: (1) graduates who had run for office prior to the training (16% of respondents), (2) those who ran after the training (32%), and (3) those who had never run (52%). As previously discussed, we focus on political novices since the factors that constrain women’s progressive ambition may differ from those keeping women from emerging as candidates (Sweet-Cushman Reference Sweet-Cushman2018; Windett Reference Windett2014).Footnote 22

To Emerge or Not TO Emerge?

A political economy view of gender and ambition suggests that because home and care work remain uneven between the sexes, women facing competing work–family demands will be less visible in politics. We use both qualitative and quantitative data to assess the importance of income, breadwinning, and household dynamics in Emerge alumnae’s decisions to run for office.

Qualitative Evidence

As a first pass at understanding the decision to emerge, we analyzed open-ended responses to the following survey question, answered only by those who had not yet run: “There are a lot of important reasons why people decide not to run for political office or find they are no longer able to. Why haven’t you run for office yet?”

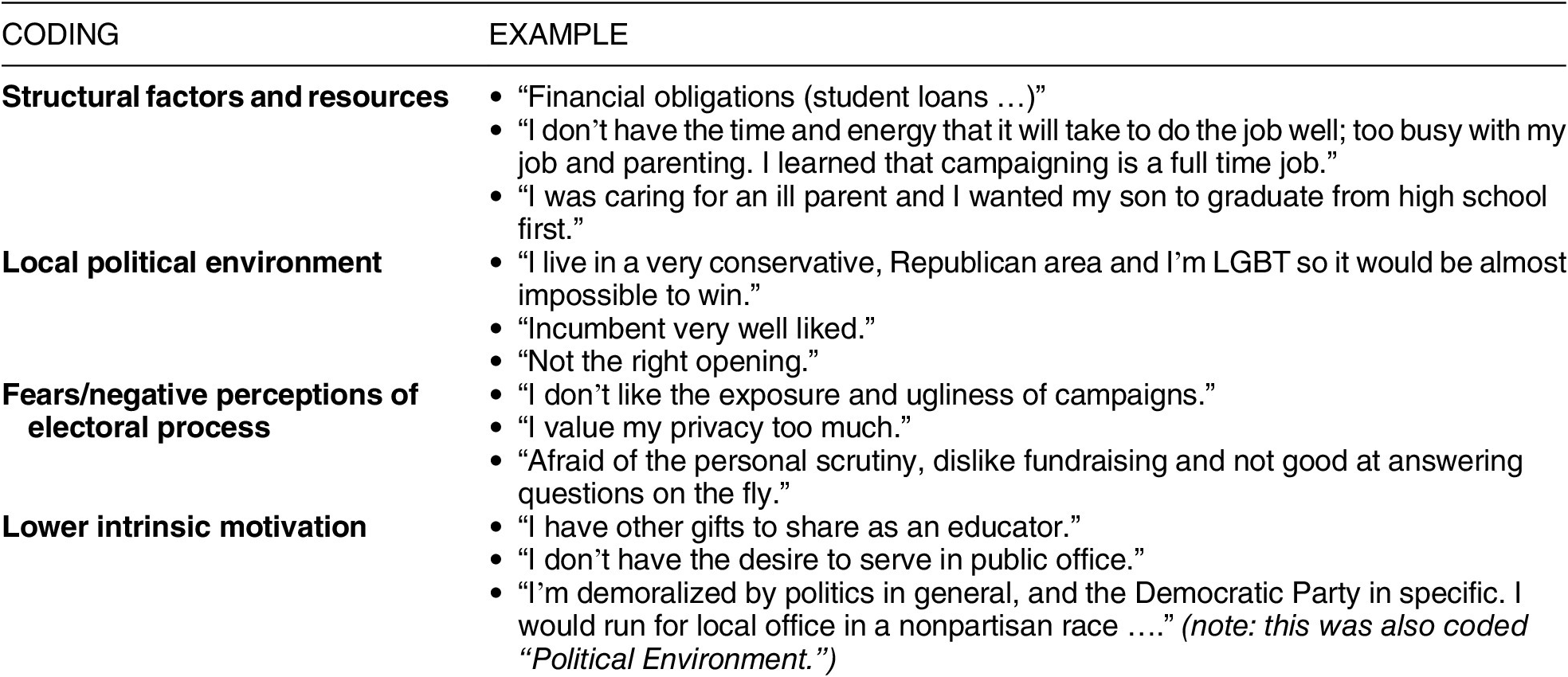

In reading the responses, we were struck by the prominence of the discussion of work–life balance, especially related to time and money. Relying on broad distinctions from the political ambition literature, we coded four types of response: structural factors and resources (marriage, personal financial situation, or time commitments such as mentions of salary, commute, time with children, etc.); local political environment (e.g., mentions of an entrenched incumbent or living in red versus blue districts); fears or negative perceptions of the electoral process (being afraid of discrimination, not wanting family privacy invaded); and lower intrinsic motivation (such as lacking the desire to serve). Table 1 presents examples of answers within categories.

Table 1. Qualitative Data Coded from Open-Ended Answers

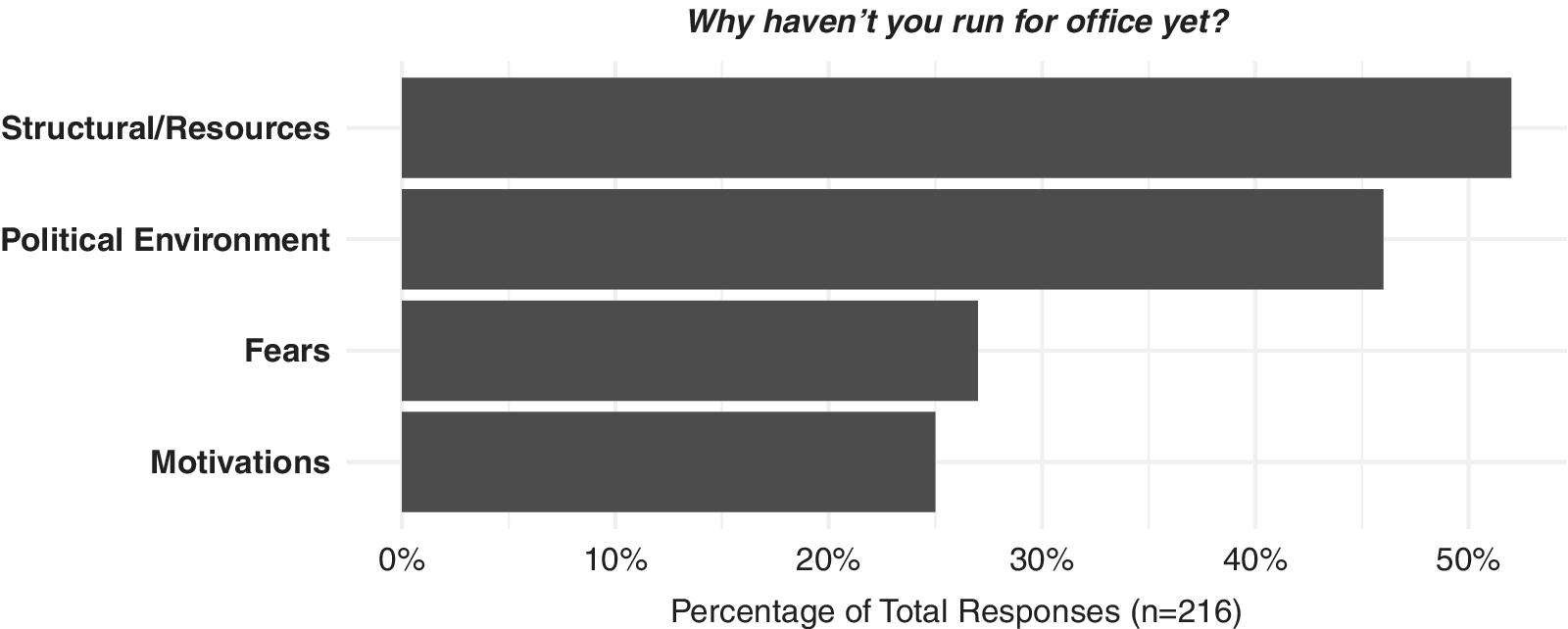

Figure 2 displays the prevalence of answers for each category.Footnote 23 Structural and resource constraints were most commonly cited; half (52%) of non-runners cited these factors as primary concerns. Consistent with arguments that link political opportunity structure to expressive ambition, 46% who had not run cited the political and institutional environment.Footnote 24 Another quarter cited fears about campaigningFootnote 25 or insufficient motivation.Footnote 26 Emerge alumnae describe their decisions in language that resonates with the scholarship on women’s ambition, but the structural explanations underemphasized in recent research were most common.

Figure 2. Deterrent Factors in Candidate Emergence

Note: Coding is of open-ended data from political novices; answers could be coded into multiple categories.

In sum, when questioned in an open-ended manner, ambitious women frequently implicate resource constraints in their decisions not to run. However, this could be due to social desirability—it may “sound better” to say one needs to pay the bills than to admit one is fearful or unmotivated. The next section investigates whether we can predict which women run using quantitative measures of household income, contribution to the household budget, and household composition.

Quantitative Evidence

Our survey, which covered household income, respondents’ contributions to that income, and household composition, allows us to examine the influence of each on candidate emergence. We first present descriptive information and then results from quantitative analyses graphically.

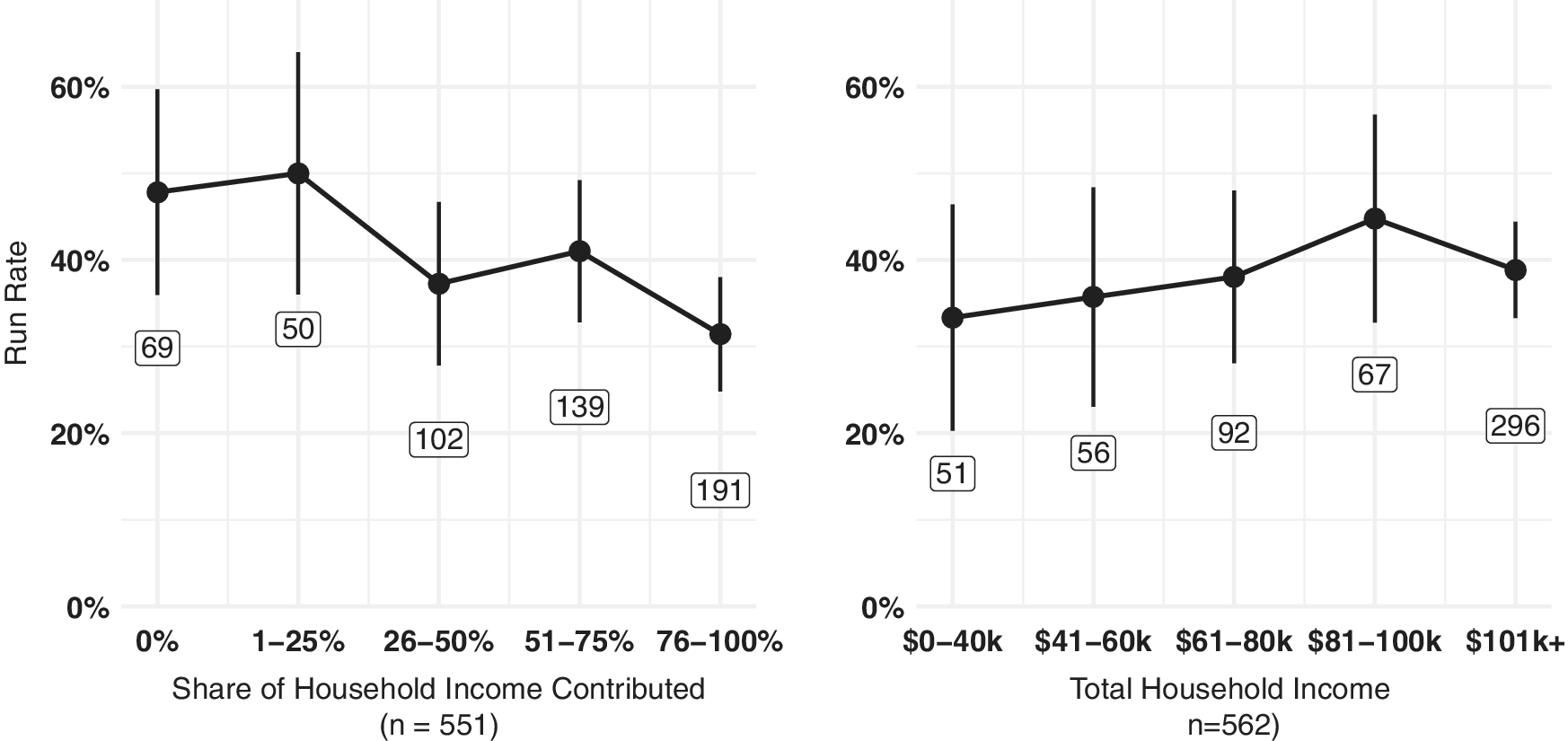

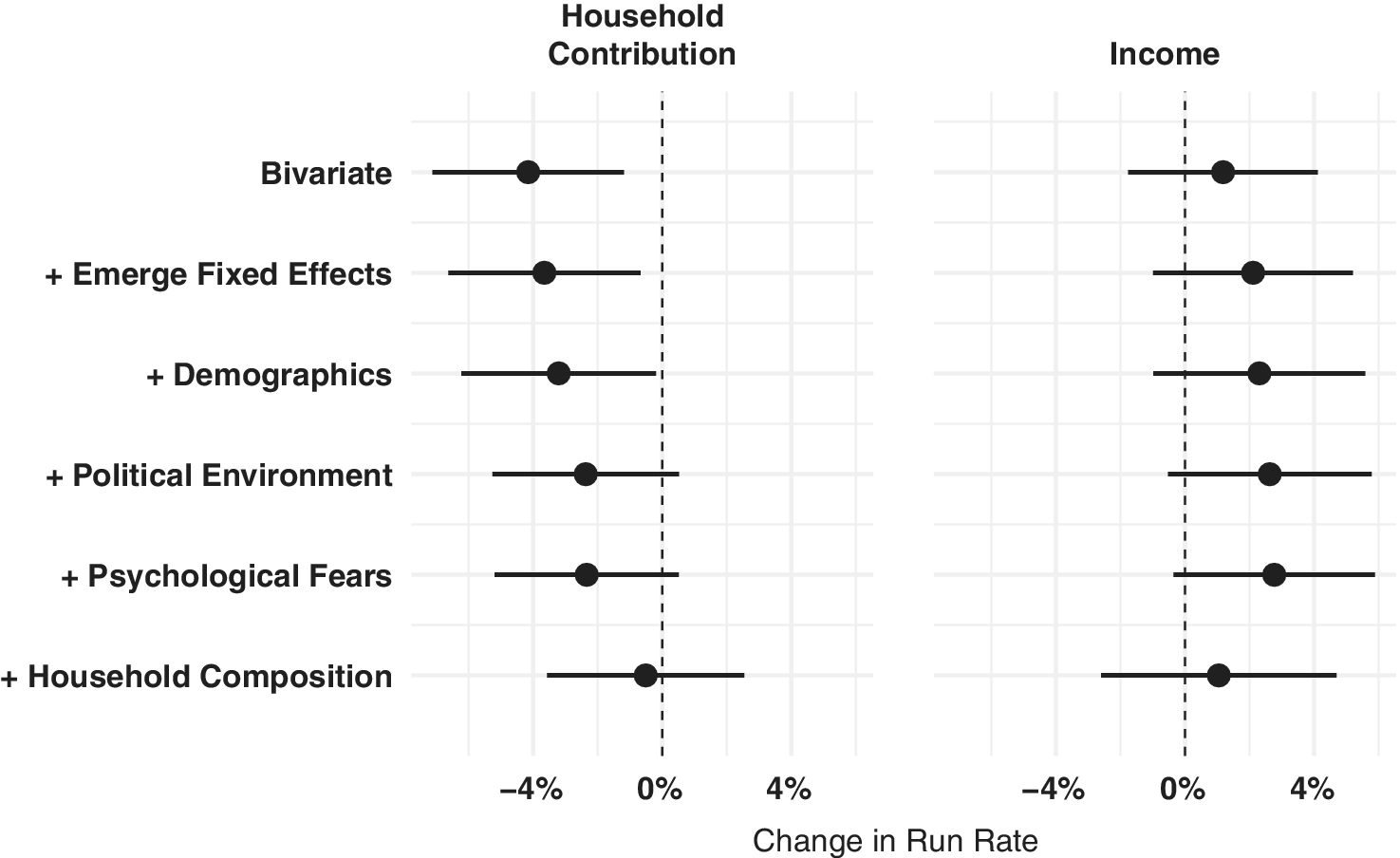

Does low income or high relative contribution constrain women’s candidacies? Figure 3 presents the relationships between candidate emergence, measured as the average run rate in each category, and different degrees of breadwinning responsibilities (left panel) and levels of household income (right panel). The means and confidence intervals come from bivariate regressions calculated with ordinary least squares (OLS), without taking any other factors into account.

Figure 3. Among Political Novices, Breadwinners are Less Likely to Run (left panel), but Income is Uncorrelated with Emergence (right panel)

Note: The average run rate by breadwinning and income categories, reported with 95% confidence intervals calculated via OLS (for novices only). The number of respondents is reported in the bubble below each category. Appendix C-4 replicates these plots with all respondents, showing that the results hold (and strengthen) when all graduates are included.

The left-hand panel of Figure 3 reveals that breadwinning responsibilities are negatively correlated with candidate emergence. Recall from Figure 1 that 39% of all political novices ran for office after the Emerge training program. The left side of the left-hand panel of Figure 3 shows that women who contribute 25% or less of their household’s income improve upon that average; the right side shows that breadwinners do not. Indeed, there is a 13 percentage-point difference in run rates as we move from women who contribute less than a quarter of the household’s income (49% ran) to women who contribute more than a quarter (36% ran). Thereafter, the relationship continues to slope downward, though less dramatically.

For novices, a t-test for the difference in run rates between women who contributed 0–50% of household income and women who contributed 51–100% is statistically distinguishable from zero (two-tailed p-value = 0.061) with a difference in run rate of -7.98 percentage points. A linear OLS regression using all household income categories is also distinguishable from zero (B = -4.15, p = 0.006); each categorical jump on the distribution of breadwinning decreases the probability that Emerge alumnae ran for office by about 4 percentage points. This finding is consistent with a breadwinner constraint: as the proportion of income that women contributed to the household increases, the likelihood of candidacy decreases.

The right panel of Figure 3 depicts run rates among Emerge alumnae whose household income falls within the bands marked on the x-axis, from $0–$40,000 up to the final category of $101,000 or more. Though there is a slight rise in propensity to run across the distribution of household income, it does not reach statistical significance. Contrary to the income constraint hypothesis, we find no correlation between total household income and the probability of running. We probe the lack of an income constraint in depth in the final section of the results.

Does the effect size hinge on other covariates? We use a second set of analyses to probe whether these relationships change when we account for other covariates. Figure 4 uses coefficient plots to present point estimates and 95% confidence intervals from OLS regressions that predict the probability that alumnae in our sample ran for office using the degree of breadwinning responsibilities (left) and total household income (right) as independent variables, with additional controls added in successive rows.Footnote 27

Figure 4. In Regressions with Controls, Household Contribution (i.e., Breadwinning) Lowers Run Rates among Novices, but Income Does Not

Note: Coefficient plots present separate OLS regressions showing how the probability of running among political novices (x-axis) is correlated with breadwinning (left column, n = 598) and income (right column, n = 562). Successive rows show how these correlations change when more variables are added to the regression cumulatively. Appendix C-3 finds similar results in noncumulative regressions, and Appendix C-2 shows the effects hold using logistic regressions.

The first row in each panel of Figure 4 shows the estimated coefficient from a bivariate regression between breadwinning (or income) and the alumnae run rate for novices. Successive rows in each figure show how the relationship between breadwinning (or income) changes when additional control variables are added to the regressions cumulatively. For example, the row labeled “Emerge Fixed Effects” shows the relationship between emergence and breadwinning (or income) when controls for state and year of graduation are added to the OLS regression. The row labeled “Demographics” also includes the fixed effects from the prior row but now adds controls for ethnicity, education, area of residence, and LGBT identification. The row labeled “Political Environment” adds controls for level of pretreatment nascent ambition and involvement with the Democratic Party. “Psychological Fears” adds a control for the respondent’s average response to a battery of questions addressing psychological fears, and “Household Composition” adds controls for whether the candidate is unpartnered and whether she has children.Footnote 28

Figure 4 shows that regardless of model specification, higher household income by itself is uncorrelated with the decision to run. Though the estimated coefficient on income is consistently positive, the confidence intervals surrounding the point estimate always include zero. However, in all specifications, a higher degree of breadwinning responsibilities is negatively correlated with running for office. The cumulative successive regressions reveal, though, that the strength of the breadwinner effect varies depending on the set of covariates included in the regression, though the point estimate is consistently negative. The biggest change in the correlation between breadwinning and running occurs when variables related to family structure—marital status and having children—are added as controls. This suggests an interaction effect.

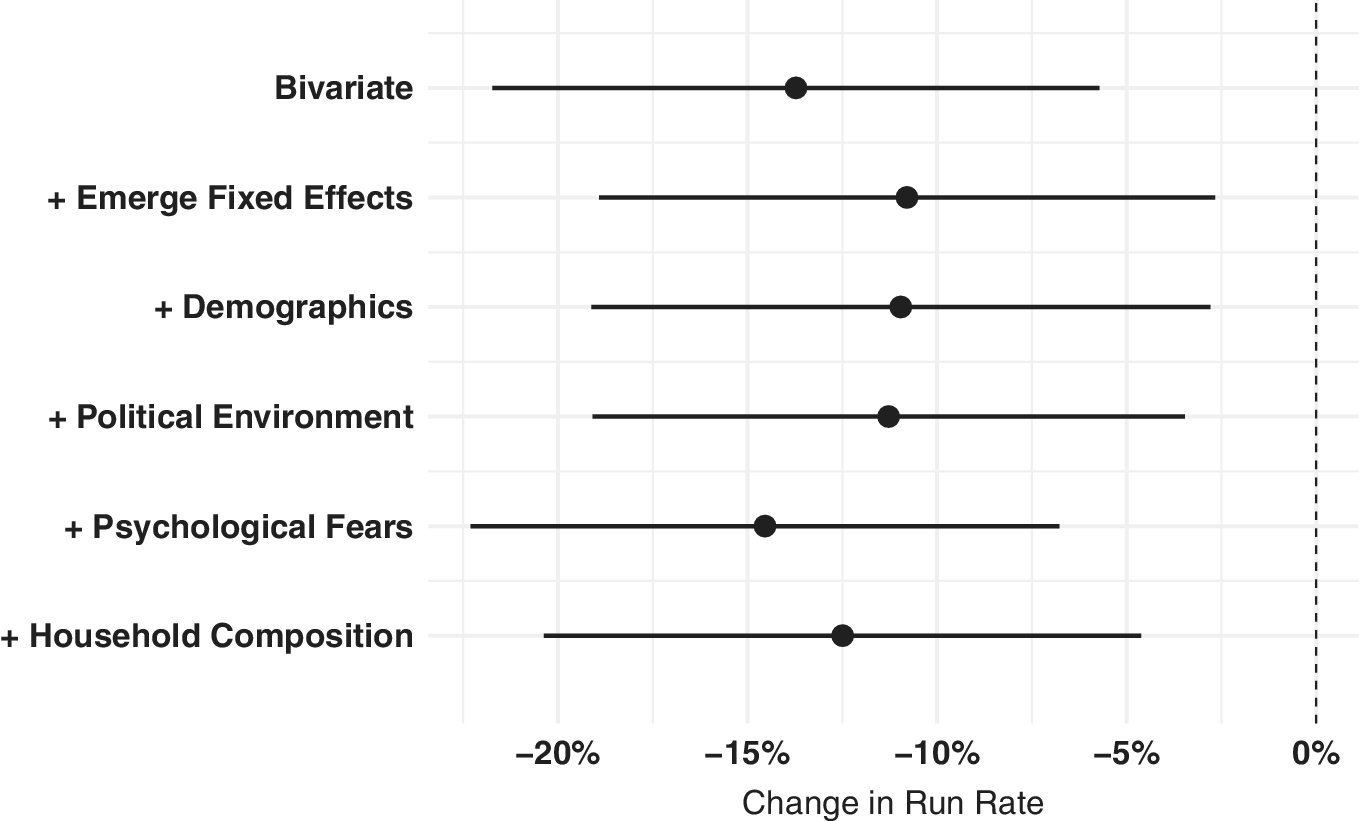

Do other measures of financial responsibility produce similar results? Next, we probe whether our claims about breadwinning (as measured through contribution to household income) are supported by respondents’ reported fear of lost income. In the survey’s psychological battery (enumerated in Appendix C-1), respondents could select as many as 15 separate “fears” they held before their first run for office. One of the fears was “losing out on income while campaigning.”Footnote 29 If we replicate the regressions depicted in Figure 4 but replace our original measure of household contributions with this measure of “fear of lost income,” we see even clearer evidence of the relationship between expressive political ambition and income, as shown in Figure 5.Footnote 30

Figure 5. Fears of Lost Income Depress Candidate Emergence among Novices

Note: Coefficient plots report predicted change in run rates based on fear of lost income using OLS with 95% confidence intervals. Only novices are included. As in Figure 4, each row adds different covariates to the preceding row’s model.

Figure 5 shows that respondents’ fears of losing income while campaigning predict a lower likelihood of candidate emergence. In the bivariate regression, we see that an alumnae’s admission of fear of lost income is associated with a 13.72 percentage point decrease in candidate emergence (p = 0.001). The estimated effect size is large because the “fear of lost income” variable is dichotomous; in fact, the substantive size of the estimates are similar to the net effect of moving from the bottom category of breadwinning (0% contribution) to the top category (76–100% contribution), which predicted a 16.6 percentage point decrease in candidate emergence. While we are reluctant to place undue weight on a single measure meant to be part of a battery, convergent validation across both measures is reassuring.

In both Figures 4 and 5, we see evidence that the possibility of losing their contributed income correlates with a lower likelihood of running. However, we also see that the strength of the breadwinner effect varies depending on the set of covariates included in the regression, though the point estimate is consistently negative. Importantly, the biggest change in the correlation between household contribution and running occurs when variables related to household composition—marital status and having children—are added as controls. This is consistent with our third hypothesis, which suggested that household composition, and specifically lacking a partner or having children, would deepen any constraints imposed by breadwinning or household income.

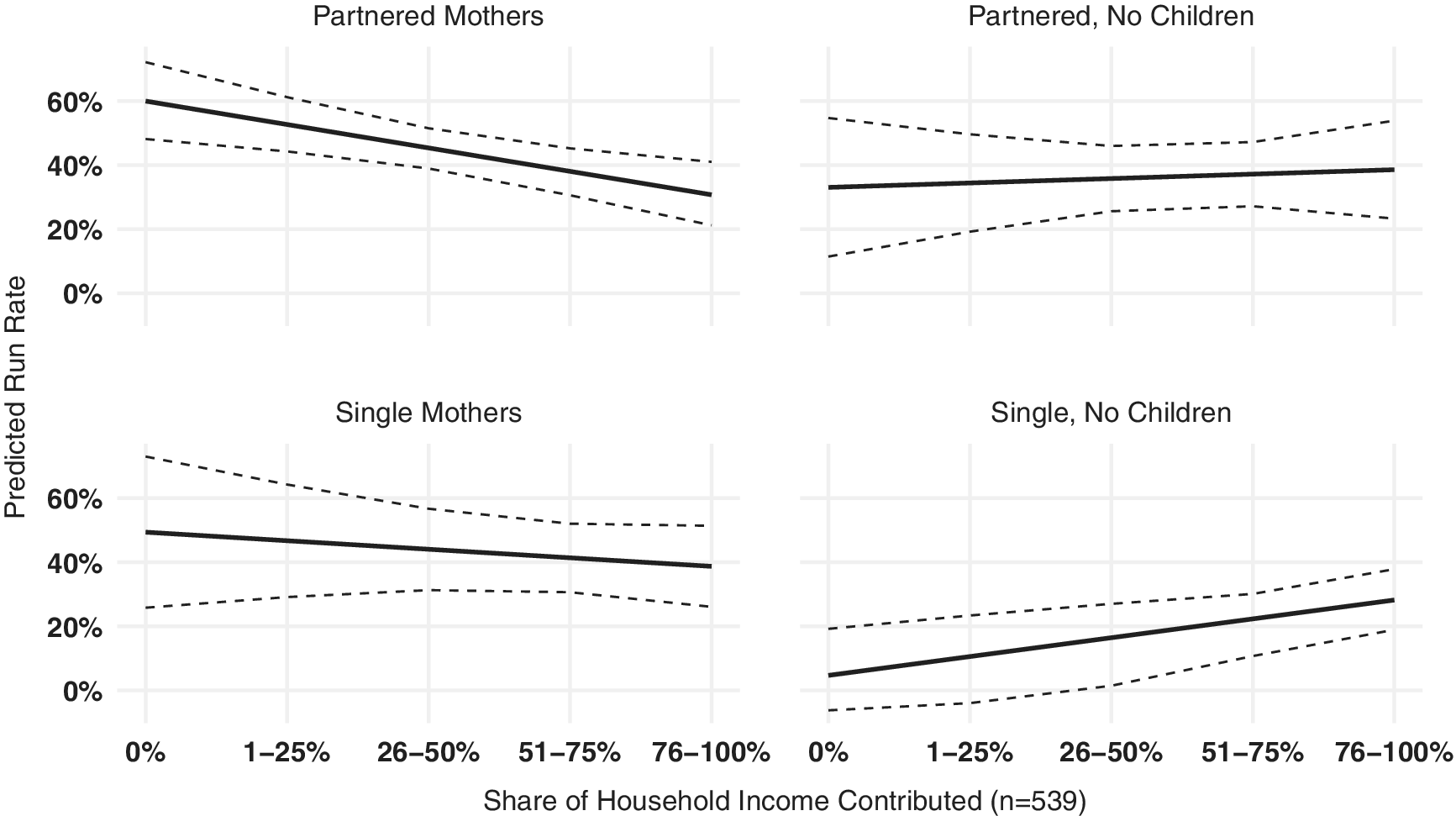

Is there an interaction between breadwinning and household composition? Figure 6 graphically illustrates how the probability of running for office (y-axis) interacts with breadwinning (on the x-axis) and household composition using logistic regression. Each subplot depicts how the relationship varies based on the respondent’s partner status and motherhood.Footnote 31 Note that women coded as “single” may not contribute 100% of their household income for multiple reasons: some are students or unemployed and receive other support (e.g., from a parent, a sibling, a roommate, etc.), some are retired or widowed and may not think of the retirement or insurance benefits they receive as income, and some are divorced or separated and receive alimony or child support.

Figure 6. Testing for an Interaction Effect: Household Composition Matters for Candidate Emergence

Note: Run rates across degree of breadwinning responsibility predicted using bivariate logistic regressions, reported with 95% confidence intervals. Only novices are included. Single respondents may not be sole contributors to household income if they are students, widows, divorced, or have other access to wealth.

We can see in Figure 6 that nonworking mothers with partners are the most likely to run for office (top left), while nonmothers are as likely to run when they are breadwinners as when they are not, regardless of partner status (top and bottom right). Mothers, whether partnered (top left) or single (bottom left), are most affected by the interaction effect between parenthood and breadwinning, which is strongly negative and significant (B = -7.12, p = 0.026). In contrast, women without children show little evidence of a breadwinner effect (if anything, the slope is slightly positive), but evidence a large intercept shift: single nonmothers are nearly 22 points less likely to run for office (p = 0.037) than are partnered nonmothers.Footnote 32

In short, the analyses in Figure 6 reveal how breadwinning responsibilities interact with women’s private responsibilities, including motherhood, to depress candidacy.Footnote 33 Notably, among women who do not have the additional burden of breadwinning, having children on its own does not depress candidacy.Footnote 34

Interpretation and Generalizability

Women trained by Emerge who have not contested an election voice concerns that their family lives and finances are not compatible with their aspirations for political office. Among the novices who responded to our survey, nearly half reported working- or middle-class household incomes, and well over half reported that they earn more than 50% of their household’s income. We do not find evidence that women from poorer households were less likely to emerge as candidates, but our statistical analyses show that women who were breadwinners, or who expressed fear that they would lose income as a result of running for office, were much less likely to convert their nascent ambition into expressed ambition than women with less financial responsibility. Depending on the measure used, breadwinning is associated with a 13–16 total percentage point gap in expressive ambition.Footnote 35

Several important questions remain. First, how confident can we be that our estimates are capturing a true relationship between breadwinning, income, and candidacy and not an artifact of Emerge’s selection process or some other omitted variable? Second, do candidates sort into more or less costly races in a way that explains our findings? Third, how generalizable are these findings to other important potential candidate groups, such as Republican women and men? We consider each question in turn.

Program selection and key alternative explanations. Our finding—that breadwinning reduces expressive ambition but income does not—might be an artifact of selection bias. If, for example, Emerge attendees who are breadwinners are disadvantaged along other dimensions potentially related to ambition, then our results would be confounded. We consider these possibilities by using our survey data to compare breadwinners and nonbreadwinners and using screening data (Appendices A-1 and A-2) to compare enrollees and nonenrollees.

Recall that Emerge has a competitive selection process where multiple interviewers and staff weigh in on a candidate’s dedication to running for office, prior service, and “star power.” From 2008–2012, the California branch interviewed 214 women, 94 of whom (45%) enrolled in the program. As part of the application packet, interviewers were provided basic demographic and employment information on applicants. We created a dataset with this information for all interviewees and examined whether enrollees that were breadwinners were disadvantaged on other observable dimensions at the interview stage.Footnote 36 Specifically, we know each applicant’s age, race, immigrant status, union membership, total household income, and whether the applicant requested financial aid to cover the program costs. Appendix A-2 compares these demographics for applicants to the California chapter who did enroll in the program against those who did not enroll.Footnote 37 Importantly, enrollment in the program was uncorrelated with the applicant’s age, race, whether they requested financial aid, union membership, or whether they were first generation Americans.

The only variable on which enrollees differ from nonenrollees is household income: enrollees came from wealthier households than interviewees who did not enroll (one-tailed p = 0.05). However, we also find that applicants asking for financial aid were not disadvantaged in the selection process, supporting Emerge’s claim that they are blind to financial need. When we linked the screening data to intake information about enrollees, we found no meaningful correlation between total household income and breadwinning (Pearson’s r = -0.12, p = 0.99). In other words, Emerge did not select breadwinning women from poorer households but instead selected women from wealthier backgrounds, regardless of breadwinning.

We suggest this finding bears on our earlier lack of evidence for an income constraint. If Emerge is more likely to admit women from wealthy families, this could attenuate the effect of income in our statistical analyses by removing variation from the lower end of the scale. Read in that light, one potential avenue by which income binds could be through elite gate-keeping, rather than through an individual woman’s self-selection into or out of politics (Carnes Reference Carnes2015; Reference Carnes2016).Footnote 38

Do these effects overlook expected election costs? Next, we evaluate whether there is sorting related to the expected costs of entering a particular political race—that is, whether wealthier women or nonbreadwinners sort into costlier or time-intensive races, while working-class women and breadwinners sort into less costly or intensive local races. If so, these factors might not appear to constrain expressive ambition, but they would nevertheless affect “where” candidates emerge.

Most novice enrollees that ran did so in local and state races; only three novices in our dataset ran in national races. Among the enrollees who ran, breadwinners were slightly more likely to enter the least expensive and time-consuming races (such as elected party committee positions) than they were to run in costlier races like state senate. In local and party races (n = 110), 60% of entrants were breadwinners; in larger municipal races (n = 68), breadwinners made up 49% of entrants; and in state-level races (n = 72), 51% were breadwinners. Overall, among women who ran, 55% were breadwinners, while among those who did not, 65% were. In other words, most breadwinners opted out of running at all, rather than sorting into less time- and cost-intensive races. To the extent that such sorting occurs (although the relationship we observe is small), further evidence in favor of a breadwinning constraint emerged. However, we find no differences in average household income by the level of office women sought.

What about Republican women? One potential concern about the generalizability of our study is that because Emerge only trains Democratic women to run for office, the dynamics we identify may not apply to Republican women. Among Emerge women, stay-at-home moms were the most likely to convert their ambition to candidacy. As Appendix E-3 shows, according to American National Election Survey statistics, Republican women are more likely to be partnered full-time homemakers with children than are Democratic women. If Republican women are structurally advantaged to express ambition based on our findings, some other factor that depresses nascent ambition must be operative.

This is exactly the finding of the growing literature on Republican women’s political ambition: Republican women tend to have even lower political ambition relative to copartisan men than do Democratic women (Barber, Butler, and Preece Reference Barber, Butler and Preece2016). Previous work attributes these baseline differences to different beliefs about social roles, ideological polarization, and increasing conservatism in the Republican Party, or to low levels of party recruitment (Gimenez et al. Reference Gimenez, Karpowitz, Monson and Preece2018; Thomsen Reference Thomsen2015; Och and Shames Reference Och and Shames2018). Republican women considering running may also anticipate voter backlash: Saha and Weeks (Reference Saha and Weeksforthcoming) find that Republican voters penalize ambitious women relative to ambitious men, especially in the context of nonpartisan races like those at the local level, and Deason, Greenlee, and Langner (Reference Deason, Greenlee and Langner2015) report that Republican voters penalized candidates who were mothers of young children relative to fathers of young children. While it is outside the scope of this paper to adjudicate this, we suspect that within a large sample of Republican women with high nascent ambition, the breadwinner effects we estimate could be even larger when paired with the party’s ideological attachment to traditional notions of motherhood.

What about men? Finally, although our focus in this study is on variation in candidate emergence among women, a historically underrepresented group, it is natural to consider how this generalizes to men. Will male breadwinners, who presumably face similar levels of risk (e.g., lost income), also have lower political ambition? Our data cannot directly answer the empirical question of whether structural or resource constraints impinge similarly on men’s political ambition, but we can gain some insight from others’ work.

Feminist scholars have long stressed that gender dynamics present greater burdens for working women than for working men insofar as household labor is still largely a woman’s domain (Bianchi et al. Reference Bianchi, Sayer, Milkie and Robinson2012, Hook Reference Hook2017, Iversen and Rosenbluth Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2006, Teele, Kalla, and Rosenbluth Reference Teele, Kalla and Rosenbluth2018). In light of this research, we suspect that the “second shift” presents a more formidable barrier to women’s than to men’s expressive ambition. In a group of elite graduate students, Shames (Reference Shames2017) finds that more than a quarter of respondents were partnered or married, and those women were already undertaking more household work than were their male counterparts. This is consistent with decades of time-diary studies showing that although men today contribute to parenting and housework, women still spend more time than men on these activities.Footnote 39 In addition, the largest to-date study of the gender gap in US political participation (not candidacy) found that even when men worked more hours in paid jobs, they also had more leisure time available for politics than did women (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001, chap. 7). Indeed, Burns, Schlozman, and Verba (Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba1997) found that even when controlling for socioeconomic and personality-based factors, husbands with greater control over home financial decisions were more likely to participate politically than expected. The same was not true for wives.

In addition to the demands of the second shift, the breadwinner constraint likely pulls more heavily on women because of key differences between the types of households in which women are breadwinners and those in which they are not. Far more women than men in the general population are nonpartnered breadwinners (Houston Reference Houston2013). Pew (2013) speaks in particular of the rising trend of “breadwinner moms,” estimating that about 4 in 10 children grow up in households run by a single woman.Footnote 40 A 2012 WSJ/McKinsey study, which surveyed over 4,000 employees at 14 major companies, found that about half of the women in their sample were simultaneously primary breadwinners and primary caregivers, while most of the breadwinner men were not primary caregivers.Footnote 41 In other words, even if breadwinning affected men and women in the same way, since there are far more women who serve as both breadwinners and caregivers, more women than men will be affected by the breadwinning constraint we identify.Footnote 42

Conclusion

Foundational research on the political economy of gender suggested that women’s political equality would increase as they attained higher levels of education and became permanent fixtures in the workforce (Burns, Schlozman, and Sidney Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001; Welch Reference Welch1977). Yet scholarship continues to document the resilience of hierarchical social norms around gender, race, and class in structuring political behavior, as well as the backlash that attempts to upend such hierarchies can engender (Brulé Reference Brulé2020; Khan Reference Khan2019; Prillaman Reference Prillamanforthcoming). Our work joins other recent interventions that cast doubt on the idea that economic progress will help women overcome the hurdles that family obligations present for public life (Gimenez et al. Reference Gimenez, Karpowitz, Monson and Preece2018, Iversen and Rosenbluth Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2006, Silbermann Reference Silbermann2015, Teele, Kalla, and Rosenbluth Reference Teele, Kalla and Rosenbluth2018).

By focusing on Democratic women—the most likely to run for office in the US—we offer a rare glimpse into the decision-making process in the liminal zone between nascent and expressed political ambition. Most broadly, we find that among women with high levels of nascent political ambition, many will never take the final step onto the public stage due to the demands of family life. For the women closest to candidacy, their ability to emerge is constrained by how they share financial burdens in the household and whether, if they have children, they can rely on another income. Consistent with claims by scholars of class and race that material resources and structural advantages make descriptive representation more likely for some groups than for others, our findings suggest that for one of the most marginalized categories of women, single moms, the road to political representation is steep.Footnote 43

Because women’s absence from politics delegitimizes democracies (Barnes and Burchard Reference Barnes and Burchard2013; Clayton, O’Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton, O’Brien and Piscopo2019), our research indicates that new interventions may be needed to promote women’s candidacies. Candidate training programs, such as Emerge, work hard to address women’s fears, often explicitly basing program choices on academic scholarship that treats psychological deterrents and recruitment as key barriers. Yet our data show that many women are unable to become candidates because of financial responsibilities at home, no matter how strongly they are encouraged and recruited.Footnote 44 If political parity is the goal, future research and public activism must explore new possibilities to alleviate the burden on mothers and breadwinners.

Electoral reforms may make progress where candidate recruitment programs cannot. For instance, recent rulings by the Federal Election Commission in favor of Liubia Shirley and M. J. Hegar, two Congressional candidates and mothers, now allow candidates for federal elections to use campaign funds to subsidize election-related child care.Footnote 45 However, interventions designed to increase women’s representation should support mothers at all levels of office: most women in public life hold local- and state-level positions, and the vast majority begin their political careers in such races (Anzia and Bernhard Reference Anzia and Bernhard2018). As states have considerable autonomy in their own elections, activists might pursue initiatives for candidate childcare allowances, “candidate leave” policies, and public funding for campaigns to alleviate such inequities state-by-state. More boldly, since nothing in the Constitution requires states to use majoritarian electoral rules, proponents of gender equality in the US might do well to push for electoral reform toward proportional representation. Comparative scholarship has shown that party list-style voting places fewer demands related to campaigning on individual politicians, and even absent electoral quotas, proportional systems tend to elect more women (Iversen and Rosenbluth Reference Iversen and Rosenbluth2010, 154).

Presently, the disparate impact of the outbreak of COVID-19 on working women, especially working mothers of young children, reminds us that women’s progress, whether economic or political, is fragile (Lyttelton, Zang, and Musick Reference Lyttelton, Zang and Musick2020).Footnote 46 Long-term changes in the gendered division of labor within the household may not be enough to transform highly qualified, ambitious women—the best bets—into candidates. Perversely, for such women, breadwinning responsibilities, a signal of the long-awaited economic parity with men, may inhibit, rather than promote, conversion to candidacy.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000970.

Replication materials can be found on Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/S1EUAF.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.