‘No water here’

‘The Plan was not accurate’, one of the most senior administrators of the Mahaweli Authority System L office, told Thiruni Kelegama in March 2014. ‘The original plan to divert water up to Weli Oya is impossible’, he continued. ‘So, without any water here how are we meant to give away new paddy land? It is simply impossible’ (government official, 18 March 2014).Footnote 1 We are in Weli Oya, formerly a highly militarized frontline in the war between the Sri Lankan army and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). Weli Oya is also a colonization scheme (the so-called ‘System L’) in Sri Lanka’s ambitious Mahaweli Development Programme, a large-scale irrigation project that diverted water from the Mahaweli Ganga (the largest river of the country) to the northern dry zone of Sri Lanka to provide water for paddy cultivation for settlers who are largely brought in from other areas of Sri Lanka. Lack of water, explained the official to us, was not an impediment to invite settlers, as the priority was to ‘bring settlers to the empty Dry Zone now that the war is over’ (government official, 18 March 2014). Since the war ended in 2009, the Mahaweli Authority has brought in over 3000 families to System L, but they are without land and water to cultivate paddy: ‘there is no sign of anything’, they complained. This situation forces them to live from dry rations provided by the government.

The settlers are brought here by the state for a bigger purpose. Indeed, these settlers are ‘frontiersmen’ of the Sinhala-Buddhist nation in the northern part of Sri Lanka: the purpose of settling them in this particular place is to fill that land with loyal citizens of the Sinhala-Buddhist nation: ‘We have a long-term plan here … With the war finished, we have to make the Sinhala man the most present in all parts of the country’, confided a military official to Kelegama (military official, 3 April 2017). A first wave of settlers, who came in the height of the war in the late 1980s, was trained as armed home guards to protect the frontier against the LTTE. A second wave of settlers, who came after the war ended in 2009, saw themselves as patriotic farmers in the service of expanding the Sinhalese settlement frontier further into the northern dry zone. The promise of land in Weli Oya has thus attracted loyal and patriotic Sinhalese to claim the territory of the northern dry zone for the Sinhala-Buddhist nation.

In Sri Lanka, development and Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism have been closely intertwined for decades,Footnote 2 and colonization schemes have been central to this agenda. Similar to the Gal Oya Scheme in eastern Sri Lanka, the Mahaweli Development Scheme is implicated in a ‘peasant politics’ that has pursued the project of a Sinhala-Buddhist nation under the guise of high-modernist development.Footnote 3 Moving Sinhalese settlers to sparsely populated areas in the northern and eastern dry zone served to expand the settlement frontier, making these settlers ‘frontiersmen’ of the Sinhala-Buddhist nation.Footnote 4 Gal Oya and Weli Oya were those schemes that moved deeply into the hinterland of provinces inhabited by Tamils and Muslims. These feared to be made minorities in their own territories and heavily opposed these schemes.Footnote 5 In Weli Oya, the settling of Sinhalese was therefore largely done clandestinely. With the civil war intensifying since the mid-1980s, the area of Weli Oya was increasingly militarized.Footnote 6

After the war ended in May 2009 with an outright military victory by the Sri Lankan military (and the total annihilation of the LTTE), the Mahaweli Authority and the military re-started activities to bring a new wave of landless Sinhalese from down south, mainly from Hambantota, the fiefdom of then President Mahinda Rajapaksa, and neighbouring districts, to settle in Weli Oya, again in a clandestine manner. As of January 2014, when Thiruni Kelegama started fieldwork, large sections of the 13 villages that came under the purview of the Weli Oya DS Division were dotted with wattle and daub houses. Numerous new families appeared to have moved to the area. Kelegama had a hard time in the field to receive a confirmation about these new settlers from government officials: First, the officials denied it (‘There are no new resettled people here’, claimed a government official at the divisional secretariat division; government official, 20 January 2014). A couple of months later, a senior official of the Mahaweli Authority, after confirming ‘are you Sinhalese?’, explained to her:

The Mahaweli [programme] here in Weli Oya restarted with the war finishing. The President felt that there was a need to finish what was started long ago … you know that the programme here was interrupted because of the Tigers [the LTTE]. Now we have begun again and that is why we are getting new people coming to live here. (Mahaweli Authority officer, 10 August 2014)

Through a detailed ethnographic study of the life histories of settlers that came to System L in two waves of colonization (the 1980s and the 2010s), we show how the settlers, who came to Weli Oya from extremely marginal backgrounds, followed the ‘lure of land’ in two senses: first, as allure of becoming land-owning farmers with a sense of patriotic mission, and second, as a sense of mission to occupy the territory for the Sinhala-Buddhist nation. But these patriotic settlers soon saw themselves thrown into highly precarious constellations: The first wave of settlers who were brought to Weli Oya in the 1980s in the midst of an escalating civil war, found themselves not only in economically miserable conditions, but had to face the violence of the LTTE. At least, they received land and water. The second wave of settlers, that came after the war ended in 2009, were left without paddy and water, as the promise of land and water by the Mahaweli Authority was premised on a technical impossibility (as the official conceded). The highly precarious conditions the settlers found themselves in and the deferred promise of land frustrated many of them, producing cracks in their unwavering loyalty to the Sinhala-Buddhist nation.

We argue that the ‘lure of land’ thereby transfigured into a ‘lie of land’: A ‘cunning state’Footnote 7 betrays its own frontiersmen—patriotic settlers—who are called to colonize the northern dry zone frontier and fulfil the long-term mission of the Sinhala-Buddhist nation. We show how the apparatus of the state with support from the military cunningly deploys a set of tactics combining subtle threats with constantly deferred promises to channel the settlers’ disappointments. The state thereby discouraged the settlers from leaving the colony—the place they were sent to occupy for the Sinhala-Buddhist nation. In a sense, this cunning of the state alludes to what Jeganathan and Ismail write in Unmaking the nation: ‘the nation—to be precise, those with the power to act in its name—has always suppressed its women, its non-bourgeois classes, and its minorities’.Footnote 8 In our case, we observe the betrayal of the non-bourgeois, subaltern Sinhalese classes, who see themselves as frontiersmen of the Sinhala-Buddhist nation. Although the sense of betrayal produced forms of protest, many settlers endured and stayed in place. The cunning state thereby, though not uncontested, eventually consolidated, and continues to consolidate, its nationalist territorial agenda.

Methodology

Thiruni Kelegama conducted 11 months of ethnographic fieldwork in Weli Oya, spread across several field visits between 2013 and 2016, followed by selected communications with some informants in 2018 and 2019, in order to get a sense of how the situation had developed since the change in government in January 2015. During this fieldwork, Kelegama conducted 15 interviews with settlers of the first generation, 22 interviews with settlers of the second generation, 30 interviews with government officials and military officers, and eight interviews with other key informants. Most of the interviews were carried out in Sinhalese and translated into English, with the remaining conducted in English. Suspicion and surveillance were omnipresent in the field, due to the clandestine nature of re-settlement in Weli Oya in 2014: ‘Weli Oya is too contested and you will have a hard time’, Kelegama was told by a government official in Weli Oya. ‘Are you Sinhalese?’ she would be asked repeatedly. Only after a reassurance that this was the case (‘she is one of us, do not worry’), would respondents be happy to talk, but often, the instruction would be: ‘No notes!’ All the sources have therefore been anonymized, i.e., names given to respondents are not their real names. This ethnographic fieldwork was complemented by archival research in the Mahaweli Authority library to screen through policy and planning documents of the Mahaweli Development Programme.

‘System L’—militarized high modernism

The Mahaweli Development Programme was always more than simply a high modernist scheme. Considered Sri Lanka’s foremost feat in post-colonial engineering, irrigation, and modernization, the Mahaweli Development Programme was positioned at the centre of the country’s national development strategy in the 1970s and 1980s.Footnote 9 It proposed the harnessing of the 335-kilometre long Mahaweli Ganga—the island’s largest river—in order to divert water to the Dry Zone for agricultural development.Footnote 10 The scheme was to increase the power-generating capacity of the country, enable the cultivation of 900,000 acres of paddy land, and settle more than one million landless families from the densely populated Southern Wet Zones into the Dry Zone.Footnote 11 Placing the stupa (temple), tank (irrigation reservoir), and the paddy field (irrigated rice field) as the hallmarks for celebrating the Sinhala-Buddhist nation,Footnote 12 the colonization schemes were seen as tools to reinvigorate a glorious past of Sinhala civilization and to uplift the Sinhala peasantry.Footnote 13

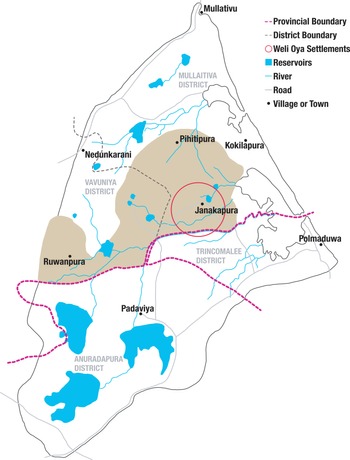

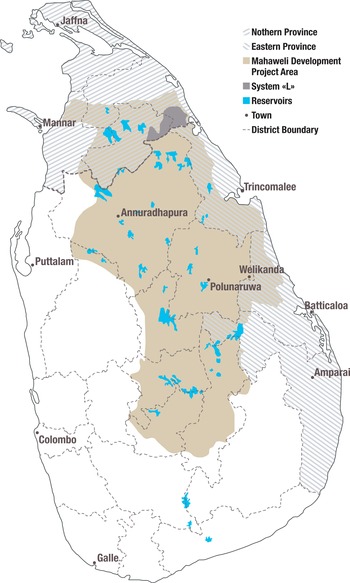

Through the Mahaweli Development Programme, a large number of Sinhala settlers have been moved to regions that had previously been inhabited by minorities.Footnote 14 This aspect of the programme came to be recognized as a significant factor contributing to the increasing civil unrest in the country, with the LTTE declaring that one of its main intentions was the ‘safeguarding of territory against planned state sponsored colonization’ carried out through the programme.Footnote 15 Of particular concern was the north-eastern extension of the Mahaweli Development Programme—the Weli Oya scheme (‘System L’) (see figure 1).Footnote 16 In his personal account For a sovereign state, Malinga H. Gunaratne, former senior Mahaweli Authority bureaucrat, confirmed that settling Sinhalese in System L, which was ‘strategically located in relation to Eelam … would destroy the land basis for the very existence of Eelam’.Footnote 17 System L enabled the insertion of a loyal Sinhala population into a sparsely populated strip between the Tamil-inhabited areas in the north and Tamil- and Muslim-inhabited areas in the east, thereby driving a geographical wedge into the claimed Tamil homeland (‘Tamil Eelam’) (see figure 2).Footnote 18

Figure 1. Location and layout of System L and new settlements (Base map: Mahaweli Development Authority; Cartography: Dani Tschanz).

Figure 2. The Mahaweli Development Project Area and System L (Base map: Mahaweli Development Autority; Cartography: Dani Tschanz).

Not surprisingly, System L was highly controversial, and the settlement of Sinhalese started in the mid-1980s rather surreptitiously. After a previous attempt to settle 40,000 Sinhalese at Maduru Oya River in Batticaloa district in eastern Sri Lanka had been abandoned due to public pressure,Footnote 19 these potential settlers, mobilized by a Buddhist monk, Dimbulagala, were relocated to settle in Manal Aru (later to be renamed in Sinhalese as Weli Oya) under System L. Technically, this was a daring move as System L had not been foreseen for the accelerated Mahaweli Development Programme, and was planned to be up for development only after completion of the former.Footnote 20 However, a clique close to the then President JR Jayawardena, including the President’s son Ravi, and senior officials of the Mahaweli Authority, acquired the land in Manal Aru through an extraordinary gazette notification.Footnote 21 The settling of Sinhalese had to be done clandestinely, however, because of public pressure and despite assurances of the government of the opposite.Footnote 22 Only in 1988 could System L be officially launched under the name ‘Weli Oya’ (sandy river in Sinhalese). The settlement in Weli Oya came under attack from the LTTE and was increasingly militarized, while the settlers were armed to defend the territory: as part of a counter-insurgency strategy, these armed settlers were deployed at strategic locations surrounding army camps.Footnote 23

After the war ended in May 2009 with an outright military victory by the Sri Lankan military (and the total annihilation of the LTTE), the Mahaweli Authority and the military restarted activities to bring a new wave of landless Sinhalese, mainly from Hambantota, the fiefdom of then President Mahinda Rajapaksa, and neighbouring districts. Again, this settlement occurred in a clandestine manner. This colonization coincided with other development schemes that the military implemented in the former war zones in a strategy to ‘stabilize a victor’s peace’Footnote 24 and to occupy and control territory previously controlled by the LTTE. These schemes included special economic zones and environmental protection zones, demarcated in previous rebel hotbeds; the excavation of archaeological sites to claim land for Sinhalese in eastern Sri Lanka; and the construction of war memorial sites of a ‘triumphalist nationalism’ in the landscape of the former war zone. The military also heavily engaged in roadbuilding across the former war zone.Footnote 25 Nationalism, post-war development, and militarization have thereby become intricately intertwined, foregrounding a process of militarization that has saturated Sri Lanka’s society for decades and that has been highly visible in the (former) war zone in the form of military checkpoints and camps.Footnote 26

In Weli Oya, the coming together of ‘peasant politics’, ‘nationalism’, and ‘militarization’ pre-dates the end of the war, however. The re-opening of System L consolidated and expanded an already existing militarized colonization scheme, thereby juxtaposing an established network of ‘old’ settlers, who had endured the war, with ‘new’ settlers who came after the end of the war. While some of the post-war developmental schemes involved heavy infrastructure (roads) or elite investments (tourism), the colonization schemes required the involvement of large numbers of ‘subaltern nationalists’ in the form of marginal, previously landless Sinhalese from the peripheries of the country and the bottom of its society. To make them effective as ‘frontiersmen’ in the northern dry zone required a skilful combination of promise, logistics, surveillance, and political tactics to make the ‘lure of land’ work for the Sinhala-Buddhist nationalist agenda.

The lure of land I: Living the myth

The ‘lure of land’ is intimately tied to the overwhelming desire and aspiration of landless Sinhalese to become land-owning paddy farmers, which promises not only economic assets, but also cultural prestige. Not surprisingly, this desire unites the new arrivals after 2009 with the old wave of settlers who arrived in Weli Oya in the late 1980s. We talked to settlers of both waves of colonization about how they decided to apply to the Mahaweli Development Programme to receive free land: in both cases, most saw this as an opportunity to start a new life as a farmer. Similar to the second wave of settlers, the settlers of the first wave remembered that the start in the new place was full of hardship, but the lure of land was strong enough to keep them in place and continue their life in the new locality.

The first wave of settlers

Indeed, many who arrived in Weli Oya in the 1980s arrived with one purpose—to realize the dream of becoming a paddy farmer. Having arrived from Polonnaruwa, Anton, who now runs a small shop, recalled why he would never leave in spite of the daily hardship he and his family faced:

We are poor people. And the chances of us being able to save our money and buying our own land was an impossible dream. With the Mahaweli giving us land, we are suddenly no longer these people who are at the bottom of the ladder, we now are people who own land. If we had left during the war, we would have been left with nothing. (settler, 18 February 2015, emphasis added)

Pointing at the shelling his house had received from various LTTE attacks and speaking of the bunker he had built in the back garden for his family, Anton was quick to point out that his life had been anything but easy. ‘True we came for the free land and didn’t leave because we had nothing, but we suffered. Maybe you can say that this free land came at a price of high suffering but at least I still have my shop and I have been able to make something out of myself’ (Ibid.). Sunil recalled receiving a half-acre of homestead land to build his house on and a further three-and-a-half acres of paddy land a few months later. ‘It was difficult at the start and people did not want to live here at all but I knew if I left I would never get any land again’ (settler, 20 February 2015).

Even for those early settlers, who had suffered heavily from the war, the lure of land—the dream of being a land-owning family—persisted. Yasawathi, who had lost her husband soon after their arrival, explained how her husband had arrived in Weli Oya in one of the buses that were provided to find themselves in the midst of a ‘wild jungle’. She remembered the many problems they had faced at the start due to the lack of water, food, and money: ‘The only way we survived was by eating one meal a day with dry rations that were given to us by the Mahaweli’ (settler, 28 August 2015). Shortly after their arrival, her husband was caught in the midst of a LTTE attack against the army and died soon after, leaving her alone with her son and daughter. Yasawathi attributes her survival solely to the Mahaweli Authority and is still immensely grateful for having been given paddy land: ‘I could not leave, I had nowhere to go. The Mahaweli sirs were so kind to me as well as the army after my husband died.’ Having received the paddy land early on, she was able to harvest it and start providing for her family slowly. ‘It was not easy’, she is quick to remark, ‘but I survived and now we are a land-owning family’ (Ibid., emphasis added).

The Mahaweli Authority, a centralized government body, was working closely with local divisional secretariat offices in different provinces in order to identify which groups of people would receive land: ‘We were giving people free paddy land and agricultural land and many did not want to let go of what they saw as a golden opportunity—the chance to become a land owning paddy farmer’, replied one of the Mahaweli authority officials when Thiruni Kelegama asked him how the Mahaweli Development Programme had managed to convince people to move to Weli Oya back in the 1980s: ‘But it was still difficult to get people to move this far up north especially given they had no idea where they were going to. We kept trying however and the promise of free land always helped’ (Mahaweli Authority officer, 1 October 2015, emphasis added). Based on these efforts, the Mahaweli Authority claims that by 1988 there were almost 3500 families in Weli Oya, which is postulated to have grown to almost 20,000 by the early 1990s, although there are no independent sources to verify these figures.Footnote 27

Sunil, Anton, and Yasawathi are all representative of the first wave of settlers who arrived in Weli Oya in the 1980s to become land-owning paddy farmers. However, while they decided to stay behind, other settlers who came with them chose to leave due to the difficult conditions that were prevalent in the area as mentioned by nearly all informants, such as the lack of employment, proper schools, and hospitals. ‘We were living in most miserable conditions’, Bandula Vithanage told us, who moved to Weli Oya in 1989: ‘We had to sit and wait for the Mahaweli to come and give us the rations each week so we could survive’ (settler, 27 August 2016). The main reason that the Mahaweli Authority gave for the high rate of return, however, was the heightened civil war.Footnote 28 Weli Oya was a border village and strategically located at the edge of the Sri Lankan state-controlled area and bordering ‘Eelam’ or the LTTE homeland; it was a site of repeated attacks starting from the late 1980s continuing until the 1990s. As a result, many settlers had to abandon their homes temporarily and move to nearby refugee camps in Padaviya until it was safe to return home. Ariyasinghe, an official from the Mahaweli Authority, explained:

The high rate of abandonment only increased as the LTTE attacks increased in the area and the settlers had to finally leave their houses. A large number of them did return to their land as they had nowhere else to go to but we do not deny that a large number of people left for good. (Mahaweli Authority officer, 15 March 2015)

The second wave of settlers

The lure of land was also motivating the second wave of settlers who came after the end of the war in 2009: many settlers expressed a long-standing desire of becoming a land-owning paddy farmer. Many of the new settlers who had come to Weli Oya since the restart of the programme had moved there to escape a life of poverty back home, and the lure of free land was strong: ‘Why would I say no to free paddy land?’ (settler 1, 20 February 2014). Janaka, who had moved from Anuradhapura, was rather vocal about why he had chosen to come to Weli Oya after the end of the war. He further added that he had no plan on leaving as he had come to Weli Oya with the sole purpose of ‘making a life for myself as a farmer’ (settler 2, 20 February 2014). Janaka was not alone in this desire and ambition to become a paddy farmer. Nalini and her husband, who had been working as temporary hired labourers in Hambantota, remembered that it felt like a dream had come true when they found out they had been chosen to receive land. She recalls being hesitant about coming to live here with her family and admitted to having some concerns:

Of course, we had no idea where we were coming and we were scared to come here because of the [Tamil] Tigers as this is the North after all, but so many people from Hambantota came with us so we felt safe … But this was our only hope and our only way out for a better future, so we came. (settler, 21 February 2015)

Jeevan, who came from Galgamuwa, expressed the gratitude he felt for being offered to receive land: ‘We had no land at all … our life was to put it very simply miserable’ (settler, 14 February 2015). Many settlers who came since 2013 hoped to escape poverty and unemployment, wanting to provide a better life for their children. However, what they faced when arriving in Weli Oya was again a life of hardship and many difficulties. As a result, many families left soon after. Problems they and those remaining encountered were scarcity of water, lack of job opportunities, and lack of access to health-care. This was compounded by the fact the paddy land that they had been promised had not been allocated to them (yet), a situation that was still unresolved as of December 2018. But, a significant number of settlers stayed on. As Jeevan told us: ‘I will not give up, I will become a paddy farmer, own land and make something out of myself’ (Ibid.).

The lure of land that the settlers of both waves of colonization responded to reflects the ‘peasant ideology’ of Sri Lanka’s post-colonial nation-building project, which echoes the central ideal that was promoted at the heart of the Mahaweli Development Programme: the importance of the village community and the farmer as the key figure who ‘will determine the future of Sri Lanka’.Footnote 29 Nationalist representations of the Sinhalese rural community were centred around paddy cultivation, which was portrayed as a ‘cultural practice coded into the bodily substance of Sinhalese people’,Footnote 30 and the lure of land was intimately tied to a socio-cultural trope of the (land-owning) paddy farmer as a figure of privilege and esteem to which these landless families aspired: ‘to make something out of myself’. The aspiration kept the settlers in the place despite all the hardship they experienced after moving to Weli Oya.

The lure of land II: Claiming back a past civilization

‘It is our duty as Sinhalese, to take back our land’ said Ravindra, one of the settlers who came after the war (settler, 10 February 2016). This patriotic settler frames a second sense of the lure of land—the lure of an ancient history of a (Sinhala) hydraulic civilization that was firmly rooted in the plains of the dry zone and that today’s settlers were now invited to reinvigorate. The prestige of becoming a paddy cultivator and land-owner thereby became entangled with a patriotic endeavour to ‘claim back the land’ that had historically been part of a large Sinhala-Buddhist kingdom, ‘the glories of Raja-Rata’.Footnote 31 Ravindra thereby expresses the territorial imperative of an ethno-religious nationalism that was intimately tied to the developmentalism of the Mahaweli Development Programme, but found its most aggressive and antagonistic form in the System L colonization scheme. In the 1980s, settling landless Sinhalese farmers in these strategic locations served the Sri Lankan state to defend the border against the LTTE, while after the war, the Mahaweli brought in new settlers to consolidate and expand the territorial occupation of the northern dry zone with loyal Sinhalese citizens.

This ethno-religious nationalism that characterized the Jayewardene period, re-emerged with a vengeance during the Rajapakse regime: It espoused a mythical virtuous Buddhist society that had been thwarted by colonialism.Footnote 32 JR Jayewardene had declared that the patriotic peasant farmer ‘and the new civilisation he will build … will determine the future of Sri Lanka’.Footnote 33 Mahinda Rajapaksa portrayed himself as the ‘warrior king’ who, by winning the war against the LTTE, had saved the Sinhala-Buddhist nation from an ‘endogenous Tamil threat’ and re-established sovereignty.Footnote 34 The patriotic farmer was deemed crucial for the spatial consolidation of the sovereignty of the Sinhala-Buddhist nation in the territories of the northern dry zone frontier, and Ravindra expressed his conscious alignment with this political vision.

Home guards of the frontier

In the 1980s, this ethno-religious nationalism was implemented not only by state organs, such as the Mahaweli Authority, but promoted and pushed forward by a network of Buddhist monks, politicians, and high-ranking government officials. A central component in attracting settlers to Weli Oya in the 1980s was the work of a Buddhist monk, Rev. Dimbulagala, who led an ‘army’ of Sinhala settlers to encroach the Maduru Oya settlements which had been reserved for Tamils under an agreement he had worked out with the then Mahaweli Minister Gamini Dissanayake.Footnote 35 In Colours of the robe, Ananda Abeysekera writes that Buddhist monks had been most vocal in asking the government to eradicate ‘Tamil terrorism’, and many accused the Jayewardena regime of not doing enough to protect the unity of Buddhist Sri Lanka.Footnote 36 Dimbulagala, in his case with permission from then President Jayewardene, the President’s son Ravi Jayewardene, and the implicit backing of the Mahaweli Authority, was instrumental in bringing the first group of settlers to Weli Oya to protect the border against the advancing LTTE.Footnote 37

Somananda, the head monk of a local temple in Weli Oya, recalled how Dimbulagala promised free land if settlers followed him. Having moved to Weli Oya as a disciple of Dimbulagala, he recalled the intensity with which the monk wanted to ‘protect the North from the Tamils’: ‘This was Mahaweli land after all that wasn’t being used so it was easy to convince people to come live here when we told them that they will soon get paddy land’ (Buddhist monk, 15 April 2016). While Dimbulagala was a convincing figure, Somananda believed it was not simply the enticement of free land but he played into nationalist sentiment by declaring that by moving to Weli Oya the settlers were helping to protect the country from the advancing LTTE. It was this persuasiveness, he believed, that convinced many people to take the risk of travelling to an unknown area with no guarantee of what to expect:

We arrived and all this was a jungle. There was nothing here and the people were told to build themselves huts. For us it was enough. We listened to our hamuduruwo [Buddhist monk], we knew he was doing the right thing, for us and for our country. (Buddhist monk, 15 April 2016)

But Somananda also admitted that a large number of people did leave as life was difficult and danger was imminent: ‘In the end we stayed behind and this area was protected because of us and today it is with pride we can call it the last standing Sinhala bastion of the North’ (Ibid.).

This view was shared by many early settlers we spoke to. They saw their move to Weli Oya not only as an opportunity to become paddy farmers but as a chance to ‘prevent the LTTE from taking our land’ and be ‘true patriots’. Silva, who arrived with Dimbulagala and Somananda, claims that not only did he want to become a farmer and own land, but that he felt this would be an opportunity to also assert what he termed his ‘Sinhala-ness’. For him, the idea of staking a claim on this empty land was tied to a larger history that was more important; he believed that the country belonged to the Sinhalese and it was their land (settler 1, 25 May 2017). UTHR reports therefore concluded that the settling of Weli Oya was carried out in order to ‘break the back of Tamil nationalist aspirations and preserve a unitary Sri Lankan state under the Sinhalese elite’.Footnote 38

The military and the Mahaweli Authority decided to arm the settlers and to employ them as home guards. Silva writes that these home guards, or militarized farmers, ‘played an effective role in supplementing and complementing the Sri Lankan security forces in defending the frontier areas’ as they were instrumental in ‘consolidating power in the areas captured by the armed forces’ in the north and east. Venugopal notes that as many as 50% of all households in border villages had one or more persons working as home guards or regular members of the security forces. These numbers are confirmed by other studies across different colonization schemes in the former war areas.Footnote 39 In Weli Oya, these armed settlers were deployed at strategic locations surrounding army camps as part of a stronger militarization and counter-insurgency strategy. Almost 75% of the males in System L were employed as home guards. Muggah reports that in the late 1990s, some 25,000 infantry and home guards were occupying the border villages of System L.Footnote 40

Early settlers like Dayapala and Ratnapala recalled in interviews doing their service as home guards with pride and honour and spoke of how it was their decision to take up arms to ensure that ‘Weli Oya remains a Sinhala-only village’ (settler 2, 25 February 2017). While many settlers explained that the daily stipend was attractive since they had no other source of income, they mostly echoed the sentiment uttered by Dayapala: ‘I was doing something for my country’ (Ibid.). Ratnapala recalled that he would have to learn how to use a gun and guard a checkpoint alongside the army: ‘I had no reason to say no. The only reason that a village like this remains in the North, full of us Sinhalese people, is because we fought for our land’ (settler 3, 10 August 2016). Yet, they were aware of its dangers: Vijaya, another of those settlers, recalled: ‘We knew it was going to get dangerous living here, this is the border between us Sinhalese and the LTTE … I did not want to leave … we learnt how to use the guns we were given’ (settler, 15 June 2017). The settlers who stayed knew why they were doing so: if not, ‘the LTTE would have gotten more in control’, Vijaya was convinced (settler, 16 June 2017).

Damayanthi recalled how she tried to convince her husband Dayapala to leave Weli Oya when they found out they would have to guard checkpoints in the face of the advancing LTTE. Arriving from Matale in 1986, the promise of free paddy land had attracted them. Dayapala was one of the first people to offer to help the military: ‘He wanted to do something for the country and felt this was his duty. He always said we are proud Sinhalese people and if we do not stand up and serve this country, who will?’ (settler, 10 August 2016). While Damayanthi expressed concerns at her husband having to learn how to use a gun and having it around her home, Dayapala admits that he took to it extremely easily. The training he received from the military was extensive, and at the end of this training, he was given a gun and ammunition that he could carry with him at all times. In addition, he was paid a daily amount of Rs. 50 per day, which turned into a monthly pay of Rs. 15,000–20,000 per month. Dayapala explained: ‘It was very easy to learn to use the gun and I liked that we were working with the army—I felt useful and valued as I was doing something in return for my country, which gave me the very land I am now sitting on’ (settler 2, 10 August 2016).

A new wave of patriotic settlers

The end of the war in 2009 ensured that these settlers no longer needed to carry arms to defend the Sinhala-Buddhist nation, but the work to claim the land for the Sinhalese had to go on. The re-opening of System L and the work of the Mahaweli Authority and the Sri Lankan military to bring new settlers to Weli Oya have to be seen in this trajectory of Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism. The premise once again was when the settlers moved to Weli Oya, they would receive the agricultural land to live on and the paddy land to facilitate the goal of becoming paddy farmers. Yet, it was also clear to the settlers who came after the end of the war that they were brought in to serve a political purpose to contribute to the revival of the Sinhala-Buddhist nation in the northern dry zone.

Indeed, a large number of settlers who arrived after the end of war in 2009 asserted that they did not come to Weli Oya simply to become paddy farmers. Many saw this chance as an opportunity to ‘reclaim the country’. Naren, a newly arrived settler, stated that the offer of free land from the Mahaweli Authority was simply a ‘God-given chance’, which would allow people like him ‘to start taking back the land of my ancestors’ (settler, 2 May 2015). Ravindra, who moved to Weli Oya in 2013, saw his presence there as not only a means of reclaiming land but as a chance to put into practice what Rajapaksa had achieved at a national level with his outright victory over the LTTE: ‘I did not come here to become a farmer, you know? The war is over and we need to take back the land that the Tigers were claiming for themselves. It is our duty as Sinhalese, to take back our land’ (settler, 10 May 2015).

Ruwan Bandara, another settler, vehemently stated:

It is only because of our President [Rajapaksa] we are even here today. I know we have not yet received our land and we believe it will be given soon but what matters more to us is that we are where we belong in this land – us Sinhalese men should be taking more land further North and this is just the start. (settler, 18 August 2015)

Such assertions of overt praise for Mahinda Rajapaksa, his government and the military were plentiful and repeated often. His victory over the LTTE was hailed as the ‘biggest victory possible for the country’ (settler 1, 20 August 2015) and ‘could have been achieved by no other’ (Mahaweli Authority officer, 12 August 2015). Even when Rajapaksa was defeated at the shock presidential elections with Maithripala Sirisena coming into power in January 2015, this devout loyalty to him remained unchanged: ‘we will always be grateful to him, not just for the land but for saving the country for us from the Tamils’ (settler, 1 September 2015).

In Weli Oya, the lure of land as socio-cultural privilege (owning land) thereby became intimately tied with the lure of land in a political sense as Sinhala-Buddhist soil or territory to be reclaimed and defended. With the first wave of settlers, this emerged through an overt demand by the state to take up arms and work as home guards manning the border against the LTTE. With the end of the war, this demand took on a different turn with the new wave of settlers becoming a moral army of support for Mahinda Rajapaksa and his militarized regime, and a territorial army of sorts to people the Sinhala-Buddhist nation in the dry zone frontier with loyal settlers.

The lure of land III: Indefinite deferral

The arrival of the second wave of settlers after 2009 ended up in deep disappointment and frustrations, however. ‘There is no sign of anything’ was a recurring complaint by settlers who had come to Weli Oya after the war. They meant that they were still waiting for their plot of paddy land that the Mahaweli Authority had promised to them as part of their ‘package’ to come to Weli Oya. While all the settlers who came in the 1980s had received land plots for cultivation and irrigation water for their paddy, settlers who arrived since 2013 had been assigned land to build their houses but the very premise on which they had moved, to become paddy farmers, was a far cry from reality. The paddy land had not been allocated even as late as December 2018, the last time we checked the situation in the field. As a consequence, the lure of land remained in a state of permanent deferral—present as a promise that has not (yet) materialized in the form of allocated paddy land and irrigation water.

This constant postponement of the allocation of land created frustration and anger among the new settlers. After repeating assurances of their loyalty to Rajapaksa and the Mahaweli Authority, it would not be long before they started to also voice their frustration because the paddy land took so much longer to be distributed. Much of these complaints were directed at the Mahaweli Authority as well as the local bureaucrats at the Divisional Secretariat offices. Three years since their arrival and with no sign of any promise being met, the settlers started to organize themselves to voice their anger and dissatisfaction. While direct or aggressive confrontation was never possible in the highly militarized setting of Weli Oya, the settlers started a series of protests to voice their demands and criticize the Mahaweli Authority for its failure to allocate the promised paddy land.

‘We took it into our own hands’, claimed Yohan (settler, 5 March 2014). Yohan was instrumental in leading a series of protests that took place in March 2014. The first protest organized by Yohan comprised six people: four men and two women. They sat directly outside the centrally located Mahaweli Authority office. From this location, they were not only visible to the Mahaweli Authority, but also the divisional secretariat office and the police station. The two women took it upon themselves to make a series of small signs, which they strung together on one piece of rope and hung above the tree they sat under. The signs read: ‘Give us our land’, ‘Mahaweli is lying to us’, and ‘Where is the System L land?’ The group of protesters all vehemently agreed that they would not move unless the Mahaweli Authority engaged in some form of talks with them and provided them with a firm date as to when they would receive the paddy land.

The first protest lasted for only two days when it was called off. Jayantha, the village secretary of one of the villages in Weli Oya claimed that an official from the Mahaweli Authority had asked him to arrange to call it off immediately: ‘I got together 60 people and we went to Yohan and told him he had to leave. The Mahaweli office gave us three jeeps to use that morning, and we scared them off’ (settler, 18 March 2014). He believed: ‘the strike was one of the most unnecessary things that happened. What people do not seem to realize is that we cannot work against the Mahaweli! We must work with them and if they think that we are fighting against them, we will never get our land’ (Ibid.). Jayantha voiced a view that indicates a continuing sense of loyalty to the Mahaweli Authority and the Rajapakse government despite the deferred promises, and at the same time, the anxiety of being let down if not showing this loyalty. Jayantha believed that Yohan and the five others had only caused more problems with their course of action. Although he was critical of the Mahaweli Authority and complained about how his life was ‘on hold’, even going so far to say that this offer of free land had ‘ruined his life’, he insisted that no one should be protesting against them. He felt that he owed the Mahaweli Authority profoundly and when asked for help or assistance, he would work with or for them as would be proven many times in the future as he was repeatedly called on for help.

After this unsuccessful attempt, Yohan organised a second protest three weeks later. This time, he gathered a group of 15 people who made their way to the same place in front of the Mahaweli Authority office. This second protest lasted a day with the military being called in; a version that was corroborated by a Mahaweli Authority official. However, Yohan was not to be deterred and did not give up. Three weeks later, he sat outside the Mahaweli Authority again. He recalled why he decided to brave the military and the Mahaweli Authority: ‘What do I have to lose? I have nothing here, no family, no money … I just want the small piece of paddy land I was promised so I can get started with my life. If the army was going to kick me out and take away my land, I thought let them do it’. He believed that his persistence, coming out of a deep sense of despair, should eventually pay off—a little bit at least (settler, 20 March 2014).

On the second day, he was asked to come inside the Mahaweli Authority office where he met with the official in charge of land distribution. On voicing his concerns, Yohan claimed he was told that he needed to be ‘patient’ and that it would simply be a matter of time before the paddy land would be distributed to all the newly arrived settlers. But, before the meeting ended, he was ‘very kindly’ told to stop with the protests as he could get ‘blacklisted’ from being allocated any land in the future (Ibid.). No date was ever mentioned to him as to when the land would be given. Even as of July 2018, Yohan still had not received any land, nor his fellow settlers. While he remained frustrated and kept talking of ‘finally giving up and leaving Weli Oya’, he did not dare do so. He lived in hope that the promise that was made to him would materialize sooner than later: ‘I have nothing to go back to and all I can do is hope that all this is not a big lie’ (Ibid.).

Conclusion

‘The [Mahaweli Development] Programme will always continue, it has for over 40 years and we have no reason to really stop it as it is more or less successful’, explained a senior official at the Mahaweli Authority office in Colombo (Mahaweli Authority officer, Colombo, 5 July 2018). This statement is certainly true for System L in Weli Oya: although the Mahaweli Authority failed to allocate land and water to the new settlers, it was ‘more or less successful’ to keep settlers living in the northern dry zone to shelter the territory for the Sinhala-Buddhist nation. Through a constantly deferred promise of paddy land and water, the government uses two registers of the ‘lure of land’ to keep the settlers in place: first, the allure of becoming a land-owning farmer with an imagination of status and wealth, and second, the ethno-nationalist aspiration to claim back land seen as historically belonging to the Sinhala-Buddhist nation.

We have shown that the ‘lure of land’ is not without contradictions, though, when it is implemented on the ground. The lure of land became a sort of ‘lie of the land’: a ‘cunning state’ keeps the settlers in place while constantly deferring the promise of land, knowing that the promised allocation of land is technically impossible. Indeed, many ‘frontiersmen’ were deeply frustrated that the promise of land that incited them to come to the northern dry zone was not coming through. They protested, but backed down quickly; even Yohan, the main ‘troublemaker’. The hegemony of the Sinhala-Buddhist nation is subject to doubts even among its most loyal patriots, but the cunning tactics of state and military ensure that these doubts do not result in open opposition or outmigration. Most of these settlers kept a deep sense of loyalty to the state, and especially for then President Mahinda Rajapaksa, and at the same time, feared the power of the state’s organs. The state’s tactics are thus premised on a betrayal of the subaltern Sinhalese who see themselves as the ‘frontiersmen’ of the Sinhala-Buddhist nation.

Our case thus sits uncomfortably within two claims proposed in the literature on Sri Lanka’s Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism and the Rajapaksa’s post-war authoritarianism: first, it indicates cracks in the working of the machinery of the authoritarian Rajapaksa regime, when it looked all-powerful in the years after the end of the war. Doubts even amongst its most loyal supporters appeared because this machinery did not deliver on developmental grounds. Second, it exposes the class contradictions inside the project of Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism, when landless Sinhalese become puppets of a cunning state for its nationalist territorial agenda. Patronage politics in the clothes of Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism and its triumphalism after the war is thus premised on a betrayal of its own subaltern kin.

This foulness of nationalism and authoritarianism as exposed in the Rajapaksa regime collapsed, when the economic crisis took up unprecedented proportions at the turn of 2020: While Yohan and other settlers had been too shy to challenge the state back in 2014, the protestors of the aragalaya (struggle) movement drove out President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, brother of Mahinda, in a spectacular seizing of the President’s official residency on 9 July 2022 to powerfully express their disenchantment with a once popular and powerful leader who had played the fingerboard of Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism so well. And yet, at the time of finalizing this article (August 2022), it is less than clear whether again the ‘cunning state’ will keep the upper hand and manage to curb and discourage further protest and political change in Sri Lanka beyond authoritarianism and Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism.

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this writing to our dear colleague and friend, late Professor Shahul Hasbullah, University of Peradeniya, for his friendship and unwavering support. Without his intimate knowledge of the research area and his tireless engagement, this research would not have been possible. We are also indebted to Urs Geiser, Alice Kern, and Bart Klem—who worked with us on a collaborative project that investigated the violent frontier in post-war Sri Lanka. Shalini Randeria and Jonathan Spencer gave important advice and feedback throughout this project. Sarah Byrne, Muriel Côte, Rony Emmenegger, Konchok Gelek, Deborah Johnson, Christoph Kaufmann, Thamali Kithsiri, Timothy Raeymaekers, Rory Rowan, Kanchana Ruwanpura, Sharika Thiranagama, Rajesh Venugopal, and Asanga Welikala discussed with us pertinent questions along the way. Fieldwork would not have been possible without Weerakoon, who drove Thiruni Kelegama with his ‘tuktuk’ into the field sites, and also became an important source of information and advice. This research received funding from the ESRC through its Non-Governmental Public Action Programme (award RES-155-25-0096), and the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF), grants no. PDFMP1_123181, 100017_140728/1, and no. 100017_149183 as well as through the University Research Priority Programme ‘Asia and Europe’ and the Department of Geography of the University of Zürich.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.