Introduction

Starting in the late 1990s, public-private partnerships (PPPs) became a key feature of the modus operandi of multilateral organizations. Since then, a large literature has arisen that addresses a number of issues related to the phenomenon, including how to ensure their efficiency, the extent to which they strengthen (or weaken) global governance in different issue areas, and how the increased business participation they enable challenges the legitimacy and authority of the multilateral organizations. This article seeks to bring that literature forward by investigating the numerous new partnerships formed following the adoption of the sustainable development goals (SDGs), in a context where businesses and governments from non-Western economies increasingly influence the multilateral system.

The United Nations defines PPPs as: “Voluntary and collaborative relationships between various parties, both State and non-State, in which all participants agree to work together to achieve a common purpose or undertake a specific task and to share risks and responsibilities, resources and benefits.”Footnote 1 In the first decade of the 2000s, PPPs with multilateral organizations arose as a response to changes of the dominant liberal world order due to globalization. John Ruggie, one of the architects of the UN's new approach to business, emphasized how PPPs were a response to the weakening of the “embedded liberalism compromise,” as a cornerstone of a liberal world order, and the need for new mechanisms to regulate and manage economic openness.Footnote 2 Implicit in this was an understanding of PPPs as a continuation of liberal ideals of international governance by cooperation, emerging out of eighteenth-century, European social philosophy.Footnote 3

A more critical literature saw PPPs instead as an expression of increased corporate influence in multilateral institutions.Footnote 4 In this view, their proliferation challenged the legitimacy of the multilateral institutions, and weakened their ability to be an arena for the contestation and modification of the global capitalist system.Footnote 5 The ensuing multilateral form has been characterized as “market multilateralism.”Footnote 6 While more critical of the implications of the rise of PPPs, these authors shared the view on the backdrop for the emergence of PPPs with their proponents: the emergence of a globalized market economy. Currently, the dominant liberal and globalized market economy is challenged by states that espouse more regulated and state dominated forms of capitalism. Particularly, the rise of China is argued to contribute to the transformation of global capitalism.Footnote 7 Yet, PPPs are proliferating as never before.

This has been particularly notable after the adoption of the SDGs that are strongly supported by the multilateral institutions. The partnership-registry established by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) expanded enormously, especially following the adoption of the SDGs, increasing from 345 in 2009 to almost 4000 in 2018.

How, then, can we understand PPPs in what may become a post-Western form of capitalism?Footnote 8 Some have argued that SDGs are playing a part in the process of “governance by goal setting.”Footnote 9 The formation of different forms of partnerships is an SDG in itself (goal 17), and partnerships are also frequently mentioned as a key mechanism for the implementation of the other goals. However, PPPs encompass a large variety of different arrangements. Although the SDGs clearly have inspired companies and other actors to register in the database, in order to conclude the significance of this, we need to study the actors involved and the commitment they make. This is what we will do in this article. Particularly, we seek to better understand whether companies emerging from state regulated economies engage differently with PPPs than those based in Western liberal market economies, such as the United States. Thus, we ask: To what extent do companies from non-Western countries participate in partnerships for the SDGs? Do the PPPs formed with non-Western companies differ qualitatively from those formed with Western companies? Finally, we seek to understand what implications this has for the kind of multilateral governance we can expect in the era of the SDGs.

We explore these questions through an analysis of the 3964 partnerships registered in the UNDP's SDG partnership registry. This registry is voluntary, and the PPPs registered there do not necessarily reflect the universe of partnerships for SDGs. Nevertheless, the registry does reflect the willingness of different actors to follow multilateral processes through to partnerships and thus gives some insight into the form that multilateral public-private cooperation takes. Our findings indicate that there are major qualitative differences between the PPPs formed with companies from Western and non-Western countries. However, there are also major differences between different non-Western countries. Indeed, while participating in PPPs reveals the willingness of companies to take on a role beyond profit seeking,Footnote 10 a better understanding of the differences between PPPs allows us to differentiate between different political roles played by companies emerging from different institutional contexts.Footnote 11

The PPPs, multilateral governance, and varieties of capitalism

There is no consensus about how to define a PPP, or about what they imply for multilateral governance. The proponents of PPPs focus on how they create synergies between different actors through enabling cooperation between international organizations, NGOs, governments, businesses, and other stakeholders (including private foundations, local communities, etc.).Footnote 12 PPPs may, in their view, contribute to knowledge-sharing and capacity building; raise norms and standards for business operations; mobilize resources from different actors; and contribute to changing practices among governments, businesses, and the population at large, beyond the actors directly involved in PPPs.Footnote 13 In brief, PPPs may contribute to a “soft” regulation of global capitalism to protect workers' rights and the environment, and achieve other social goals. According to Andonova, PPPs are an institutional solution to pressing challenges faced by the multilateral institutions, initiated by “entrepreneurial actors” within them.Footnote 14 They can be considered a networked governance mechanism focused on the collaborative achievement of joint goals, with the potential of filling spaces of existing “governance deficits.”Footnote 15

However, PPPs are also associated with the increasing power of private companies, which seek to make use of the multilateral institutions to protect their interests.Footnote 16 According to this view, companies' interests in cooperating with multilateral institutions is based on a desire to improve their reputation, without fundamentally changing their practices.Footnote 17 Seen from the side of the multilateral organizations, PPPs could be understood as an example of “trasformismo”—a top-down strategy attempting to curb opposition to neoliberalism.Footnote 18

Irrespective of how the implications for multilateralism were viewed, it was increasingly accepted that PPPs, corporate social responsibility (CSR), and other initiatives implied a new form of “corporate citizenship” with significant political implications.Footnote 19 This recognition formed the basis for the argument that PPPs with multilateral organizations amounted to a new form of “market multilateralism” that coordinated relations, not only between states, but also between states and non-state actors under the aegis of multilateral organizations. According to this perspective, the motives of business are not purely self-serving: businesses do not use the partnerships solely to improve their image or contribute to the expansion of markets. Yet, goals of the collaboration or means to achieve commonly agreed upon goals that run counter to the interests of the corporations are “ruled out” or kept off the agenda.Footnote 20 Mechanisms employed to reach the goals of the collaboration make up either for market failures, for regulatory failures, or for the detrimental consequences of oligopolistic market structures.Footnote 21 This “market multilateralism” was the result of numerous actions (and non-actions) by states, multilateral organizations and businesses that, taken together, shaped the contours of a new form of global regulation.Footnote 22

However, this literature was mostly written before companies from China and other emerging economies seriously challenged the dominance of large Western corporations. Thus the differences in incentives and stakeholders facing corporations at home were not problematized much, as they increasingly were in the literature on CSR.Footnote 23 However, building on the literature on the varieties of capitalism, there is an emerging argument that the nature and extent of companies' engagement in global governance activities depends on the form of capitalism that characterizes their home base.Footnote 24 Different forms of capitalism are characterized by differences in the institutions of corporate governance, industrial relations, training and education, and the structuring of inter-firm relations.Footnote 25 While there are many possible ways of categorizing them, Detomassi distinguishes between private (or finance) capitalism, corporate capitalism, and statist capitalism.Footnote 26 The first is associated with an Anglo-Saxon model in which companies exist to produce return and increase shareholder value. The second depicts a Western European and East Asian model in which government exercises a guiding hand over the domestic economy by acting in close collaboration with its major economic agents to achieve mutually desired and compatible goals. The third is characterized by direct state involvement in the management of companies, as in, for example, China. This differs from that of the United States and some European countries in that the primacy of the Chinese state–society complex ultimately rests with the state and a state class organized around the Communist Party.Footnote 27 Also, other emerging economies are characterized by a “state-permeated capitalism” that may lead to a more “mercantilist” or neo-Listian global order.Footnote 28 When companies originating in state permeated forms of capitalism engage in governance and CSR activities, they do so for different purposes than those based in a private or corporate capitalist system. For example, many incentives provided by local and national governments and the Communist Party shape the CSR role that companies choose to play.Footnote 29 This contrasts to companies from private and corporate capitalist forms where markets, NGOs, suppliers, and providers are expected to be more important.

These features of the local institutional context may also shape the kind of engagement that the different companies show with PPPs in association with multilateral institutions. We find it instructive to categorize PPPs into five groups based on their functions and the roles of business. Local implementation partnerships are local investments to support one or several goals of the multinational institutions. Businesses contribute mainly in the sector in which they generally operate, and responsibilities and benefits are shared between public and private actors. Therefore, these are not necessarily very demanding for businesses, as they mostly do not require them to deviate from regular business practice.Footnote 30 Resource mobilization partnerships include traditional charity and sponsor activities. Often the companies involved have their core business in sectors other than the focus of the partnership. They contribute with funds or “in kind.” Advocacy partnerships aim to raise awareness among the general public or specific groups about issues of importance for reaching common goals. Businesses contribute with knowledge, technical equipment, or networks. Policy partnerships may be divided into two sub-groups (though many also straddle them). Private policy partnerships seek to improve business practices through developing standards (e.g., environmental, social) or committing to adhering to them. Public policy partnerships seek to influence policies of governments or international organizations to strengthen common goals. Operational partnerships are often the most demanding. These seek to change production practices and markets. Businesses commit not only to change standards for production of goods and services, but to change production patterns altogether. The different types of PPP are summarized in table 1.

Table 1: Typology of PPPs

We hypothesize that the probability that a company engages in a particular kind of partnership depends on the form of capitalism of their home base. State capitalist companies will be more likely to participate in local implementation partnerships that will contribute to the home state's goals; companies, whether formally private or state-owned, will acquire political or other benefits from contributing to these in their home context. Resource mobilization and advocacy and policy partnerships assume a more independent role for companies and may be more common in private and corporate forms of capitalism. Particularly, advocacy partnerships, we suggest, are likely to be associated with private capitalism where companies are concerned with image. Operational partnerships are also primarily associated with these kinds of capitalism, since states and public organizations could achieve changes in production patterns more efficiently by directly regulating companies in state forms of capitalism.

Partnerships and the SDGs: governance by goal setting?

Some have argued that SDGs are playing a part in what might be called “governance by goal setting”—a form of arms-length governance in which norms and standards are extended to a diversity of actors through the setting of common goals.Footnote 31 The rapid increase in the number of partnerships reported in the UNDP registry has occurred as SDGs have come into play; and given the emphasis placed on partnerships in these SDGs, it is reasonable to suggest a strong causal link. Can one then conclude that the SDGs will indeed exert a strong influence on the extent and form of new partnerships? There is reason to doubt this.

The origins of SDGs can be traced to two sources: the post-millennium development goal (MDG) process and the follow-up to the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro in 2012. The former was dominated by big donors with the MDG vision and followed a rather standard UN process. The latter was led by the Open Working Group (OWG), mandated by the Rio + 20 Outcome Document, and was dominated by middle income countries. Of these two parallel streams, it was the latter that proved the more influential. This was also the one that emphasized the role of business most, following up the Rio + 20's call on the private sector to engage in responsible business practices, such as those promoted by the UN Global Compact. However, research indicated that business involvement in these processes were dominated by European and U.S. companiesFootnote 32 and that a number of limitations reduced the impact of business involvement.Footnote 33

The SDGs differ in several other important respects from the MDGs. First, the SDG process was more open to non-state actors, including business. A second, important feature of the SDGs is that the goals apply to all countries of the world. This contrasts with the MDGs, which were—even if not explicitly—taken to be concerned primarily with low and middle-income countries. Third, the SDGs include a greater emphasis than the MDGs on “means of implementation,” an issue which was granted its own specific goal (17): Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development.

There was significant debate concerning the indicators to be used for the nineteen targets under goal 17 that were considered both vague and difficult to measure. Targets 17.16 and 17.17 refer more explicitly to “multi-stakeholder partnerships.” The former target seeks to “enhance the global partnership for sustainable development,” the latter more specifically to “Encourage and promote effective public, public-private and civil society partnerships, building on the experience and resourcing strategies of partnerships.”

These targets are translated into indicators. Indicator 17.16.1—for which UNDP and Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) are the custodian agencies—is: “Number of countries reporting progress in multi-stakeholder development effectiveness monitoring frameworks that support the achievement of the sustainable development goals.” Target 17.17.1 is “Amount of United States dollars committed to (a) public-private partnerships and (b) civil society partnerships.”

There was much discussion on where and how to register partnerships. The World Bank, as the designated host, proposed to use their existing registry of private participation in infrastructure (PPI) as a basis for 17.17.1 (a), but were unable to propose any source for 17.17.1 (b). Although the PPI data baseFootnote 34 is well established, to adopt this would imply a narrow definition of public-private partnerships, and a very narrow definition of “multistakeholder partnership.” And, as noted, there is still no designated source for indicator 17.17.1 (b). Faced with this unresolved situation, we have chosen to use one of the sources that might ultimately be adopted, namely the UNDP registry. This registry was originally set up following the World Summit on Sustainable Development (WSSD) in Johannesburg in 2002, that launched PPPs as a so-called Type II solution.Footnote 35

There is growing research on the use of performance indicators as contemporary practice in global governance. These studies show that indicators are seemingly neutral but have deep effects on reconceptualizing norms and shaping behavior that are not always visible, articulated, or benign. Quantitative indicators are inherently reductionist and can only capture a part of the full social objective.Footnote 36 They are intended to be—or are seemingly—“objective” and “neutral”; yet they take “what might otherwise be highly contentious normative agendas and convert them into formats that gain credibility through rhetorical claims to neutral and technocratic assessment.”Footnote 37 Indicators are instruments of self-regulation that create incentives for actors to align their priorities and discourse with the norm. They do not rely on the enforcement of legal frameworks but on social pressure.Footnote 38 They use symbolic “judgments” that create reputational damage through naming and shaming.Footnote 39

The SDGs provide an excellent example of this “governance by numbers,” as demonstrated by reference to a number of case studies in Fukuda-Parr and McNeill.Footnote 40 The case studies analyze the process of moving from 17 goals, through 169 targets to 232 indicators, and show that indicators are proposed, which are very specific, and incentivize certain actions, which do not necessarily reflect the intended aims of the original agenda. However, SDG 17 seems to offer an interesting counter-example. It is proving difficult to establish suitable indicators, which has created a situation in which the definition of a partnership is loose, and the appropriate source of authoritative data of performance uncertain. As a result, there is a lack of clarity as to how performance is to be measured, which permits or even encourages claims of performance, which are difficult to check.

PPPs: from MDGs to SDGs

The partnerships that were formed during the MDGs period showed different results regarding the extent to which they contributed to the implementation of agreed goals. A study that analyzed all of the 345 partnerships in the database with so-called “Type II partnerships” showed that while these were portrayed as instruments to implement agreed goals, in fact, they also had strong political dimensions and were heavily influenced by powerful actors, such as large businesses and the United States. Most partnerships were led by countries that traditionally participate actively in multilateral cooperation.Footnote 41 Bäckstrand and Kylsäter not only found that PPPs are dominated by rich countries, they also found a strong bias towards governments and NGOs. Governments from the industrialized world are active in 76.9 percent of the PPPs, while business actors participated in only 45 percent. However, a significant number of the partnerships were implemented in non-OECD countries. Chan (Reference Chan, Pattberg, Biermann, Chan and Mert2012) found that 19.4 percent of all the partnerships in the database were (partly) implemented in India, whereas 16.7 percent were (partly) implemented in China.

What is more relevant for our analysis is that Chan found a difference between partnerships implemented in authoritarian and democratic contexts. While the former were the most effective in achieving their goals, the PPPs did not produce what he calls a “partnership governance”—a form of governance based on cooperation, consensus, and contracts rather than hierarchical command structures. For example, partnerships in China are primarily expected to deliver and to increase output, not to change norms or institutions.Footnote 42

This contrasts with the general finding of the results of the MDGs, namely that the partnerships had limited overall impact. 37 percent of the MDG partnerships produced no output at all in terms of the criteria applied, and the output of another 43 percent could not be attributed directly to their stated goals.Footnote 43 They also contributed little to the funding of the UN institutions. Although there exists no reliable aggregate figures on development finance provided through PPPs, a review of partnerships formed by a selected number of UN organizations showed that the private sector contributed less than 1 percent of their budgets.Footnote 44

As a response to the mixed results, a range of principles and guidelines have been developed in the UN system.Footnote 45 According to these, PPPs should: (1) Serve the implementation of internationally agreed goals, nowadays especially the SDGs; (2) be coherent with national law and priorities, respect international law; (3) be in line with agreed principles and values; (4) be transparent and accountable; (5) provide an added value, and complement rather than substitute commitments made by governments; (6) have a secure funding base; (7) be multi-stakeholder driven, with clear roles of the different partners.Footnote 46

Profile of the partnerships in the partnerships for SDGs registry

The first step we did to research the questions above was to organize all the 3964 partnerships in the Partnerships for SDGs Registry in a separate database according to countries and actors (participation of businesses, NGOs, local and national governments, and multilateral organizations, labor unions, academic institutions). The Partnership for SDGs Registry is voluntary, and many partnerships may, of course, exist that support the SDGs but are not registered here. However, we believe that most actors are interested in the visibility that registering in this database provides, and that there are few costs or disadvantages related to being included in this registry.

The second step we undertook was to divide the countries into four groups: OECD countries; Brazil, Russia, India, and China (BRICS countries); other emerging countries; and developing countries (the rest). There is no perfect fit between this categorization and the division between Western/non-Western, nor the different capitalist contexts proposed by Detomassi (private, corporate, and statist). Therefore, we will also divide between regions and between countries (further on, when we look at forms of partnerships). The division is further complicated as there are OECD countries that we would normally think of as emerging (Chile, Mexico). However, this provides a start to give us an idea of what groups of countries are more or less over-and underrepresented.

Division of partnerships across categories of countries

A simple division into regions gives us the picture shown in table 2. European countries are involved in the highest number of partnerships, followed by Africa and Oceania.

Table 2: Distribution of partnerships according to regions and business involvement

The distribution of partnerships divided into categories of countries is shown to the left in figure 1. However, this does not take into account country size. As all the BRICS countries are large (except perhaps South Africa, with its fifty-five million inhabitants), this leads to a biased picture. The right part of figure 1 thus shows the density of partnerships taking size (population) into account. It shows that BRICS countries still lag significantly behind OECD countries in terms of forming partnerships.

Figure 1: Distribution of partnerships on country groups

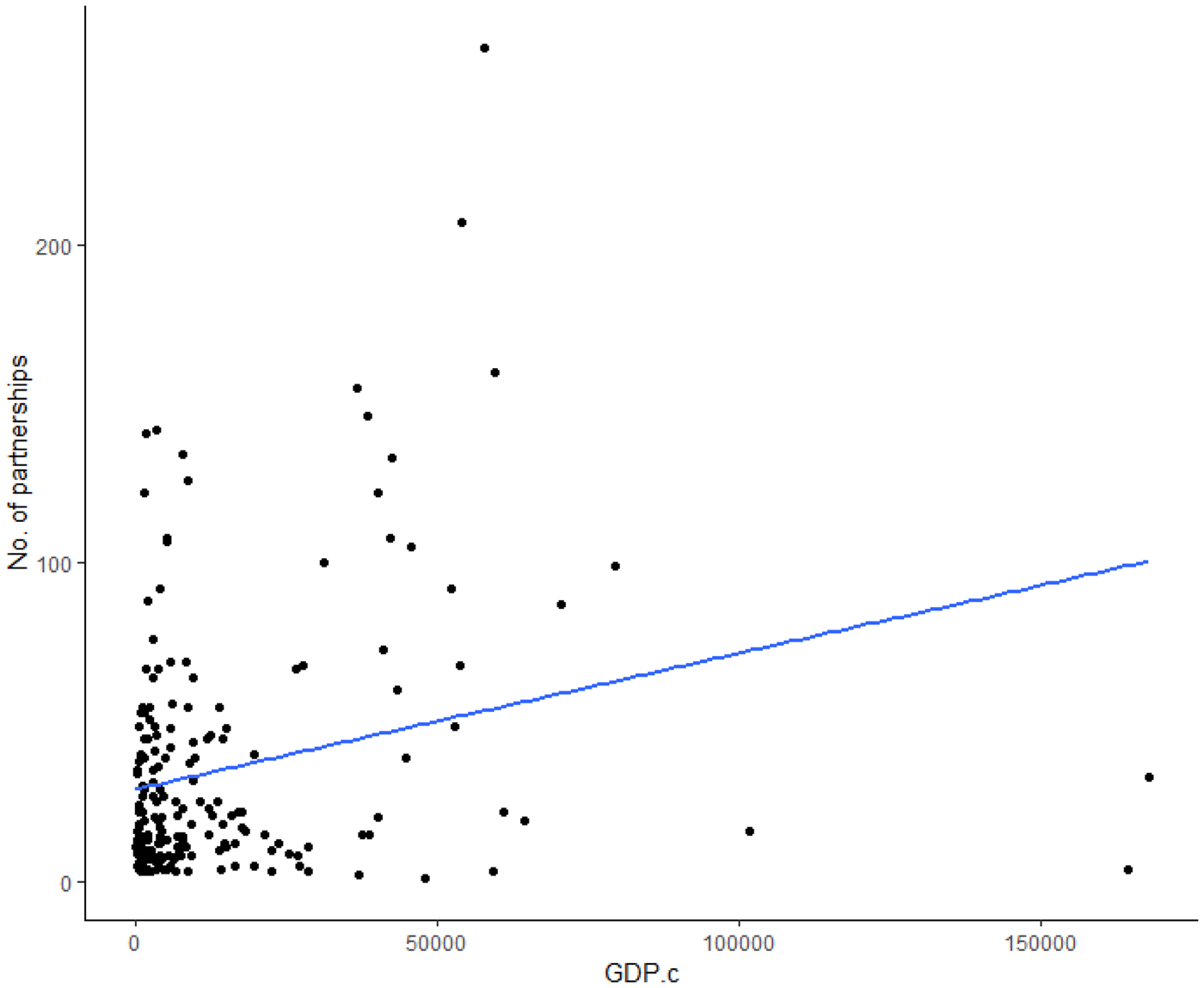

Taking GDP into account partly explains these differences. There is a significant relationship between number of partnerships and GDP per capita, which explains in part why OECD countries have a higher propensity to form PPPs than other countries (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Number of partnerships per country versus GDP/c

Business involvement in PPPs

A further difference between partnerships from different categories of countries is the extent of business participation in them. Considering the strong emphasis on PPPs as a driver of business participation in the achievement of the SDGs, it is interesting to note that only about 10 percent of the partnerships registered in the SDG partnership registry include private companies. There is a total of 1267 private firms that are registered, divided between the 3964 partnerships that are included. Several of the partnerships with private companies include more than one company, while 90 percent do not include businesses at all. These are partnerships between multilateral organizations, governments, private foundations, and/or NGOs.

However, there is a strong geographical difference regarding whether there are private companies engaged in partnerships, as seen in table 2. Only 5.9 percent of partnerships with African countries have private companies as partners, whereas 12 percent of the partnerships in which European actors are involved do, and 23.8 percent of the partnerships with the United States and Canada do so. Of the partnerships that include BRICS countries, 11.7 percent include business partners; lower than United States/Canada and Europe, but higher than developing countries.

We have also looked at the kinds of companies that are involved. First, we distinguished between national and foreign firms. National firms may also be global but they are defined as companies that have operational presence (subsidiaries) in the country where the partnership is implemented. Of the 1267 companies registered, 1183 (93 percent) are national companies. The remaining 7 percent are only involved in the countries of implementation due to the partnership. We have furthermore distinguished between private and state = owned companies. Only seventy-four companies are state = owned; twelve of these are from Germany, ten are from Brazil, five are from South Korea, three are Chinese, and three are Indian. The remaining forty-one are distributed between thirty-three countries spread across the categories listed above. In other words, there seems not to be a BRICS bias towards state-owned companies. However, this result must be interpreted with caution as the meaning of what a private company is differs strongly across countries. For example, of the twenty-six Chinese companies that are registered, twenty-three are stated to be private. Some of this may be explained with a presence of foreign owned companies with Chinese subsidiaries in partnerships implemented in China. However, to really understand the operations of these, one has to look further into individual partnerships, as we will do in the next section.

The content of partnerships

In assigning partnerships into the different categories proposed in table 1, we chose to divide into individual countries rather than groups of countries, as it is difficult to lump a group such as BRICS into one single type of capitalism. We have on the one hand, the United States, as an example of “private capitalism.” On the other extreme, we have China, being a typical example of “state capitalism.” Russia would have many features of the same, whereas Brazil, India, and South Africa have features of both, with Brazil being a much less open and more state protected economy than the other two.

It was not possible to categorize all the partnerships due to missing information. However, we have studied and categorized all the fourteen Brazilian, six South African, and four Russian partnerships; sixty-five of the U.S. partnerships, twenty-one of the Indian partnerships, and fifteen of the Chinese partnerships. The distribution is found in table 3.

Table 3: Partnerships formed with the United States and BRICS

There are strong differences that emerge, as shown in table 4. First, the partnerships in which U.S. companies participate are on average larger and more complex than those formed with partners from the other countries. The greatest difference is between U.S. partnerships and Chinese partnerships. In the partnerships in which a U.S. company takes part, there is an average of 3.5 U.S. companies, in addition to companies from many other countries, whereas there is an average of two Chinese companies in the partnerships that includes Chinese companies, with little non-Chinese company participation.

Table 4: Distribution of partnerships with companies of different nationalities involved

This is partly a reflection of the kinds of partnerships that the companies participate in. The U.S. partnerships stretch across all the categories, except local implementation partnerships. The category where we find most U.S. companies (40 percent) is policy partnerships, many of which are partnerships to contribute to changing business practices. A typical example of such a policy partnership is the OneLessStraw pledge campaign. This seeks to commit restaurants to avoid the use of plastic straws. It also has an “advocacy component” in that it strives to educate the public about the effects of single use plastic straws on health, environment, and oceans. The business partners are mainly companies that aim to reduce their own use of plastic straws.

The second most common category of partnership for U.S. companies to participate in is advocacy partnerships (26 percent). One example is the Survive to Thrive Global partnership to end domestic violence. It seeks to influence and enhance the public's understanding of domestic violence, through educating the public on the numerous policies that prevent victims of abuse from seeking help. While the main partner (Johnson & Johnson) operates within health, it is not a partnership that makes concrete use of their expertise. Rather, the advocacy work contributes to strengthen the image of the companies as working for a commonly understood goal.

Many partnerships with U.S. companies are also in the operational partnership category (20 percent). The Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Partnership (REEEP) is an example of a large global partnership that straddles many categories, including the operational. It works to reduce CO2 emissions by investing in clean energy markets in developing countries. Its donors are mainly sovereign countries and large private foundations. The private businesses involved are consulting and renewable energy companies (Energy & Security Group, ICF International, Intrinergy, Owens Corning, Morse Associates, Inc., The Regulatory Assistance Project (RAP)) that contribute to the operational transformation. Thus, this has features of being an operational partnership, as well as advocacy, policy, and resource mobilization.

This profile stands in stark contrast to that of the partnerships where Chinese companies are involved. Sixty percent of those are local implementation partnerships, typically including an international organization or a governmental agency and one or two Chinese companies. One example is The Village and the Earth partnership that works with local government in Yalop, a poor village in China, to improve the electricity facilities and develop renewable energy, giving the six hundred households in the village access to electricity. The partner is Shanxi Jinshang Energy Asset Management (Beijing), an electricity investment company. Another example is One Planet Living, a commitment to develop Jinshan into a low carbon community. This is a partnership to build the Zero Carbon Office Building within Jihnshan and develop it into the Green Building Demonstration Zone of Southern China. The private sector partner is China Merchant Property Development, a real estate company.

Compared with the U.S. companies, more of the Chinese companies are also involved in work that is close to their core operations, and there are more state = owned companies involved. A good example is the Reduction of Carbon Emissions from Idling Diesel Drayage Trucks at Container Shipping Ports, which is a shipping container conveyance system that aims to eliminate short-haul, dirty drayage trucks from a portion of the world's shipping ports and intermodal logistics terminals. Its private sector partners are a large, state-owned equipment manufacturer (Shanghai Zhenhua Heavy Industries Co., Ltd. (ZPMC)) and the state-owned China Communication and Construction Company, which also is the main shareholder in ZPMC.

There are also examples of Chinese companies that are involved in advocacy work and partnerships that straddle many different categories. Yet, these are all subsidiaries of multilateral companies, such as in the China Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP), which aims to reduce neonatal mortality and morbidity caused by preventable conditions, such as birth asphyxia, through ensuring at least one trained and skilled health worker is present at every hospital delivery. Here the main private sector partner is the China subsidiary of the U.S. pharmaceutical company Johnson & Johnson.

The broadest and most ambitious partnership that includes Chinese companies is Countering Desertification and Land Degradation, which is a partnership between United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP) and the Elion Resources Group for greening 10,000 square kilometers of desert by 2022. Elion Resources Group is a Chinese company focusing on ecological restoration and green financing. China Merchant Property Development is also a partner.

Partnerships with Indian companies also show several special features. Compared to Chinese companies, they are more varied and fall into several of the categories. Some are local resource mobilization partnerships, such as the Sustainable Food Production in Model Farms, India, or the Open Shelter Home for Underprivileged and in Conflict with Law Children. However, there is a larger share of operational, advocacy, and policy partnerships, and—most noticeable—there are many more cases of Indian companies participating in large, global, often cross-cutting partnerships, such as the REEEP described above or the Methane to Market Partnership, a policy, advocacy, operational, and resource mobilization partnership that seeks to promote methane capture-and-use in agriculture, coal mines, landfills, and the oil and gas sector. We also find a much larger share of foreign subsidiaries participating in the partnerships in India than in China. Indeed, at least four of the partnerships simply consist of subsidiaries of large multinational companies that sponsor some good cause or committment to change practices (such as the Nestlé commitment to expand nutrition education to teenage girls in India).

There are very few Russian partnerships. Two fall into the global, diverse partnerships category: REEEP and Methane to Markets that are described above and that also include a large variety of partners from other countries. One is a project in which the Russian oil company Lukoil sponsors a project run by the ILO on Youth Employment in the Commonwealth of Independent States. In the final one, a Russian publishing house is a partner in a partnership for online access to research on the environment.

The Brazilian partnerships also have their peculiarities. As with the case of India, Brazilian companies participate in large, global partnerships, such as Methane to Market and the Montreal Protocol Ozon Action Programme, where the airline Varig is a partner. However, Brazilian companies also participate in several policy partnerships that aim to change the practices of the companies themselves. This includes the Cement Sustainability Partnership where the large, cement producing industrial conglomerate Votoratim is a partner, and a partnership to enable global replication of the innovative Ethical Fashion Initiative, where the Brazilian fashion company OSKLEN is a partner. The partnerships in which Brazilian companies participate also stand out as several of them originated in the UN Global Compact initiative. The only straight resource mobilization partnership (the Financial Education for Girls Program) has a foreign subsidiary (Credit Suisse) as a partner.

Partnerships with South African companies also show some particular characteristics. Most of the South African companies participate in large global initiatives including REEP, the Global Wastewater Initiative, WIPO The Marketplace for Sustainable Technology, and Safe Water Systems. The rest are mainly relatively traditional aid projects with a private sector partnership component.

Summing up the analysis of partnerships involving business, the profiles of those of the United States are clearly very different from those of the other countries. U.S. companies are involved in a large amount of partnerships with very varied profiles. Eighty percent of the partnerships are advocacy or policy partnerships aimed to change attitudes, provide knowledge, or change policies and practices of companies, governments, and communities. We also find a group of resource mobilization partnerships where typically the companies are from different sectors than the focus of the partnership. These are, in other words, to some extent more in the category of traditional philanthropy. This profile fits well with the expectations for companies from “private capitalist” contexts, with high degrees of independence and a high concern for image and market-relations.

The partnerships that Chinese companies are involved in are, to a much larger extent, specifically project based partnerships where the companies undertake investments or provide other goods or services in partnership with governmental actors. Very few of the partnerships appear as distinctly privately driven, as expected from companies based in state-penetrated economies.

It will require more in depth scrutiny to understand why Russian companies are basically absent. One possible interpretation is that although Russia is also a partly state-penetrated economy, Russian companies do not face the same incentives for participation from their own national and local government to participate, as the Chinese.

The rest of the BRICS-countries show a profile that reveals, instead, their hybrid positions between being developing countries and emerging economies. We find many PPPs driven by foreign multinationals in a diversity of categories and others that are difficult to distinguish from traditional aid projects. However, we also see companies from Brazil, India, and South Africa participating in partnerships in different categories. Although much more research is needed, this may suggest that in these countries, with arguably weaker institutions, we will not see a very clear pattern of PPPs.

Conclusion

There has been a considerable increase in the number of reported partnerships in recent years that seems to be associated with SDGs. These are very diverse indeed, but some patterns do emerge. Partnerships in which U.S. and European governments and companies are involved still dominate numerically, although partnerships with Chinese and other emerging and developing economies are increasing. We do find significant support for the claim that actors based in different forms of capitalism engage in different forms of partnerships. First, although business involvement in partnerships is overall low, business participation is much higher in partnerships with counterparts from the United States or Canada, than from other countries. Moreover, most U.S. PPPs are either traditional philanthropy (as in some resource mobilization partnerships) or they are focused on advocacy or policy work. Without being too cynical, one might conclude that it is more important for companies from “private capitalist” contexts than others to engage in these kind of partnerships. This may be interpreted as a result of market competition as well as the strong presence of NGOs that makes company-image an important factor in survival and profit-making. Forming PPPs may be what Bäckstrand and Kylsäter calls a “legitimization strategy,” not only for the multilateral organizations, but also for the companies.Footnote 48

The strongest difference is between the PPPs in which U.S. Companies participates and those in which Chinese companies participate. The latter are overwhelmingly local, focusing on specific challenges. The companies mostly participate in PPPs within their own sector and partner with governmental institutions. This is what might be expected in state-capitalist economies, in which companies, whether officially private or public, strongly depend on responding to incentives from the state. The suggestion by Chan (Reference Chan, Pattberg, Biermann, Chan and Mert2012) that these PPPs adhere much more to a “hierarchical” than a “partnership governance” logic is supported by our findings.

Although this is only a first exploration of the partnerships registered under the aegis of the SDGs, we may suggest some implications for multilateral governance. First, as the number and diversity of partnerships have increased, the term “market multilateralism” launched to depict a form of partnerships supporting a set of social goals but within a global capitalist economy seems less relevant than before. Many of the partnerships are mostly local, mostly state led, and with business being little more than a local provider of goods and services. Indeed, the many PPPs in China contribute more to a “state capitalism” than to strengthening a market-economy. The PPP appears to be a flexible institutional form, possibly compatible with a number of different forms of capitalisms, from “private” to “state-led.”

Second, while the SDGs are, in many cases, beginning to operate as a form of arms-length “governance by goal setting,” the case of partnerships (under goal 17) may prove to be somewhat different. The SDGs do indeed serve as an instrument of global governance, insofar as they incentivize both national governments and private companies to report the establishment of partnerships. But the SDG indicators relating to partnerships are, in contrast to those of other SDGs, not very clearly specified. As a result, the numerous partnerships that are being registered may, in fact, represent very little in terms of changing practices and behavior.

In summary, it appears that joining the UN registry is an attractive option for a company, but for reasons that vary across different forms of capitalism: for companies operating in a “private capitalist” system it may be an opportunity to enhance their reputation—whether locally or globally—at minimal cost. In state capitalist contexts, the motivation is rather to enhance the reputation and relations to state-institutions upon which the companies depend to thrive and survive.