Starting from the early 1970s, European commercial banks played a pivotal role in the financing of military regimes in the Southern Cone of Latin America and Brazil. This article examines this using recently disclosed archival evidence from a wide variety of actors: commercial banks (Lloyds Bank, Midland Bank, Barclays Bank, Crédit Lyonnais, Société Générale), central banks (Bank of England, Banco de Mexico), and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, whose archives are held at the National Archives of the United Kingdom.

Apart from contemporary political magazines that addressed the complex links between banks and authoritarian regimes, this article is related to several strands of scholarly literature that look at the financial flows to Latin America between the first oil crisis, in 1973, and the debt crisis of 1982.Footnote 1 First, it relates to a large body of literature that examines the debt crisis from a political economy perspective: namely, that borrowed capital was often used to build vanity projects or finance rearmament policies.Footnote 2 Second, this article is related to a broader business history literature that examines the relationship between entrepreneurs, financiers, and nondemocratic political regimes. Finally, this article also relates to scholarly literature in both transitional justice and Latin American history that analyzes the role of nonstate financial and business actors in authoritarian contexts.

Robert Devlin and Ricardo Ffrench-Davis, for example, argue that “bank loans . . . were in many cases used for the import of unessential consumer goods, military expenditures, or to finance capital flight and unmanageable fiscal deficits.”Footnote 3 Eric Calcagno notes that the most remarkable aspect of Argentina's huge foreign debt was its use of borrowed capital for ends other than investments and that US$10 billion of the US$44 billion of Argentina's debt corresponded to “unregistered imports,” which the World Bank suspected of being weapons.Footnote 4

Political scientists have also produced excellent panoramic views of the period of “debt-led growth.”Footnote 5 Barbara Stallings tackles the political consequences of private bank loans, arguing that the debt privatizations of the 1970s had deep political implications. First, external capital flows divided the Third World; second, they undermined progressive governments; and finally, they supported reactionary regimes.Footnote 6 With respect to the bankers’ perception of authoritarian regimes, Stallings argues that bankers ranked macroeconomic and political stability highly. Writing at the time, she noted that the relationship between highly repressive governments and international bankers was “not coincidental,” because for international banks strong governments were “necessary to assure the stability and predictability that . . . will make their investments safe and profitable.”Footnote 7

The investments had to be safe and profitable not simply to generate profits for the banks but also to receive the support of home governments that relied more and more on commercial banks to shore up exporting industries. As most governments in developed countries felt the pressure of a deteriorating balance of payments, they began to look for potential new customers around the globe. Most of the time, potential buyers in developing countries did not have the liquidity to pay for imports, so commercial banks became the crucial trait d'union between surplus and deficit countries. In this respect, Philip Wellons argues, Western governments and commercial banks in the 1970s entered an “alliance” to achieve goals that both sides wanted.Footnote 8 This important aspect, which previous literature only touched upon, will be explored further in this article.

To contemporary scholars the centrality of foreign capital to authoritarian regimes in the Southern Cone and Brazil did not pass unnoticed. Jeffry Frieden argues that “external finance was central to the growth process [of Brazil].” In the case of Chile, Frieden states that “foreign finance flowed into Chile in large quantities from 1976 to 1982.” As for Argentina, “the public firms that did most of the borrowing were those involved in investment projects in industries the military favored (especially steel and armaments) and in the energy and transportation sectors.”Footnote 9 This article builds on these pioneering findings based on recently disclosed archival evidence.

A broader business history literature has examined the relationship between entrepreneurs, financiers, and nondemocratic political regimes. A particular interest was devoted to the links between German banking institutions and the Nazi regime during the 1930s.Footnote 10 Harold James concludes that “Deutsche Bank helped in the implementation of the regime's policies.”Footnote 11 More recently, business historians have focused on the relationship between multinational companies and right-wing dictators in Central America and the links between international finance and Communist regimes.Footnote 12 Comparable archival-based studies centering on the regimes of the Southern Cone and Brazil remain limited; a recent exception is an article on the activities of the multinational corporation Akzo and its affiliate company Petroquímica Sudamericana during the Argentine military dictatorship. Willem de Haan ultimately argues that Akzo and its affiliate became “silently complicit in the crimes against humanity that were committed in Argentina.”Footnote 13 With regard to the banking sector, apart from the work of James on Deutsche Bank and the Nazi regime, the literature is still very limited. Nerys John has written about the campaign, known as End Loans to Southern Africa (ELTSA), against British bank involvement in South Africa during Apartheid but does not specifically address or use archival material regarding the activities of banks like Barclays or Midland.Footnote 14

In recent years, scholars specializing in both transitional justice and Latin American history have analyzed the role of nonstate actors.Footnote 15 Legal scholars like Horacio Verbitsky and Juan Pablo Bohoslavsky recognize financial assistance as a particularly “underdeveloped area” of research but, unfortunately, the lack of archival research led Bohoslavsky to conclude, incorrectly, that “there is no consolidated data on loan volume and lender identity.”Footnote 16

Historians have done a better job at substantiating their claims. Eduardo Basualdo, Juan Santarcangelo, Andrés Wainer, Cintia Russo, and Guido Perrone analyze in detail the activities of the Banco de la Nación Argentina (the largest commercial bank in Argentina) and conclude that the bank was the “financial arm of the regime.”Footnote 17 Claudia Kedar and Raúl García Heras have made extensive use of archival material from multilateral organizations, such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), to analyze their relationship with military regimes in Argentina and Chile.Footnote 18 Despite these seminal contributions and the relevance of multilateral financing to Latin America during the 1950s and 1960s, most of the capital that Latin American authoritarian regimes received during the 1970s came not from official lenders but from private creditors. By 1985, commercial banks owned more than 50 percent of long-term debt in Latin America, compared with just 19 percent for bilateral and multilateral institutions.Footnote 19

Thus, in order to disentangle the complex financing mechanism of military regimes in the Southern Cone and Brazil, the focus must shift from official lenders to the source from which most of the financing came: that is, commercial banking institutions. This article seeks to provide new archival-based understandings of European banks’ relations with military regimes in the Southern Cone and Brazil by investigating the role of European commercial banks. The article will foster a deeper understanding of the financial dimension of the regimes that have ruled most of Latin America by including the agency of “the individuals, bodies, and companies that supplied goods and/or services to the dictatorship.”Footnote 20

European banking archives, unlike their American or Japanese counterparts, are more open to academic researchers, permitting a more authoritative account of the business relations between military regimes and international financial actors. Documents in financial archives are especially illuminating, as internal correspondence shows the inner functioning of international banks and the shifting perceptions associated with the new military regimes. The scale of the involvement of European banks in Latin America needs to be emphasized. American banks held only one-quarter of global banks’ claims on developing countries that were not members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), less than one-fifth of claims on OPEC members, and less than one-tenth of claims on eastern Europe.Footnote 21 Moreover, British and French commercial banks’ share of lending to Latin America in the total lending was the largest after that of the United States and Spain. By 1985, international credits to Latin America accounted for 19.3 percent of total loans in the case of British banks and 8.7 percent in the case of French banks, compared with just 6.5 percent for West German banks.Footnote 22

International Banking Expansion in Latin America

During the 1950s, financing to Latin America was dominated by foreign direct investment (FDI) and bilateral aid from American institutions, including the Export-Import Bank (EXIM Bank), and from a handful of Western countries that would later form the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD; known as the Organisation for European Economic Co-operation [OEEC] until 1961).Footnote 23 FDI and official lending were extended at fixed interest rates, on favorable terms, on a long-term basis and were repayable in local currency.Footnote 24

The 1960s saw a modest increase of bilateral aid while multilateral aid emerged as a new, but secondary, source of financing thanks to organizations such as the International Finance Corporation (established in 1956), the Inter-American Development Bank (1959), the European Development Fund (1959) of the European Economic Community, and the International Development Association (1960) of the World Bank.Footnote 25

European banking strategies largely mirrored the overall path of capital flows.Footnote 26 The two world wars and postwar capital controls marked a clear break with pre-1931 patterns as European banks remained on the sidelines of the financing process, with the exception of banking institutions with historical links to Latin America, such as, for example, the Deutsche Überseeische Bank, founded in 1886 by Deutsche Bank; Sudaméris, founded in 1910 by Banque de Paris et de Pays-Bas and Banca Commerciale Italiana; and the Bank of London and South America (Bolsa), founded in 1923.Footnote 27 Merchant banks such as Barings also remained relevant actors in the financing of public works. These multinational banks, which had few domestic operations in Europe, were called “overseas banks” at the time. They were active in local banking, export finance, and short-term commercial credits. In contrast, large European domestic commercial banks were mostly absent from the region. For example, Midland Bank, the largest of the British clearing banks after World War II, did not have a single branch in Latin America. It relied on correspondent relationships in international transactions.Footnote 28 U.S. banks were also not especially more active, with National City (later Citibank) the only exception.Footnote 29 In 1955 National City generated 11 to 16 percent of its loans, deposits, and earnings from sixty-one branches abroad, mostly in Latin America, compared with more than 30 percent of its loans, deposits, and earnings from eighty-three foreign branches in 1930.Footnote 30

Until the mid-1960s, Latin America continued to rely on official loans and FDI while commercial banks played a supportive role as supplementary financiers in IMF-endorsed stabilization plans and World Bank projects or as cofinancers of Western projects.Footnote 31 Overall, private commercial banks kept a “very low profile in the region's external finance.”Footnote 32

In the meantime, the initial economic success of import substitution industrialization (ISI) gave way to increasing skepticism starting from the 1960s. Orthodox economists criticized the “inward-looking” character of the ISI model, especially the high tariffs and lack of macroeconomic discipline.Footnote 33 Dependency theorists argued that the economic development in Latin America and other dependent countries was a reflection of the growth in dominant countries that resulted from the unequal economic and social structures inherited from the colonial era, which had not been sufficiently challenged by the older generation of desarrollistas.Footnote 34

Economic problems coincided with political turmoil (what Guillermo O'Donnell aptly called the “political activation of the popular sector”).Footnote 35 In Argentina, the economic plan of finance minister Krieger Vasena (1967) was accompanied by violent protests, which culminated in the so-called Cordobazo in May 1969.Footnote 36 In Brazil, the killing of teenage student Edson Luis in Rio de Janeiro unleashed a long confrontation between the military and students that pushed President Artur da Costa e Silva to issue the infamous Institutional Act No. 5 (AI-5), which suspended remaining civil and political liberties.Footnote 37 In Chile, the economic crisis of 1967 resulted in an explosion in the number of strikes, from 693 in 1967 to 1,127 in 1969, and produced an increased polarization of the Chilean society.Footnote 38

Although social unrest persisted, the authoritarian response led to a renewed interest in the region from European commercial banks. Two Barclays managers spent three weeks in Argentina and Brazil in 1970 to study a possible expansion of the bank. They perceived opportunities: “It makes sense . . . to direct some small part of our resources to countries that now have reasonable economic stability, favourable economic growth, and which do not at present suffer either from racial tension or antipathy to private enterprise, and which welcome foreign capital.”Footnote 39 In Brazil, the two managers liked that “the regime is favourably disposed to private enterprise and commands the confidence of business men.” In Argentina, they praised the military regime of General Juan Carlos Ongania, remarking that there was “tolerance, no racial problems, and an air of liberty, even though there are no free elections and the military govern.”Footnote 40 Nonetheless, despite the gradually changing political spectrum in Latin America, investments by European banks remained modest, as they lacked the know-how, staff, and capital to launch an overseas expansion.Footnote 41 Continued political instability negatively affected the expansion in the region too. Official sources of financing remained the norm. By the end of 1968, they represented around 60 percent of the region's external financing, while bank lending accounted for only 10 percent.Footnote 42

During the late 1960s, European commercial banks started to reconsider their conservative stance on international presence. Barclays decided to dissolve its overseas bank Barclays DCO, created in 1925, and create Barclays Bank International (BBI).Footnote 43 This move was much more than a simple change of name; it reflected a gradual shift away from being a “Commonwealth bank operating on a branch basis mainly in the colonial or ex-colonial territories.”Footnote 44 Increasing capital controls within the Sterling area and a devaluation of the British pound in 1967 showed that the colonial banking model was no longer sustainable. The bank started to look to new opportunities, notably to the unregulated Eurodollar market that had emerged in the 1960s.Footnote 45

Barclays became an example for other large European commercial banks. Lloyds Bank decided to acquire full control of Bolsa—in which Lloyds had already held a minority interest of 19 percent by the late 1960s—and merge it with Lloyds Bank Europe (LBE).Footnote 46 The acquisition resulted in the creation of Lloyds & Bolsa International Bank Limited, which in 1974 became simply Lloyds Bank International (LBI).Footnote 47 Crédit Lyonnais created its international office in 1969 and reshaped it in 1972.Footnote 48 Société Générale reshaped its international activities in 1974, when Marc Viénot joined the bank as deputy general director after many years spent in the French civil administration and international organizations. British and French banks opted for different strategies to expand abroad: British banks created new vehicles in the form of international subsidiaries, while French banks kept international activities under one roof. As we will see, this state of things would affect decision-making structures and risk-management policies.

Despite the historical importance of these changes, the new international vehicles did not suddenly modify the geographic focus of European banks. Overall, Latin America, with the possible exception of Brazil, did not figure as a priority for European banks. In its first five—year plan, BBI referred to Latin America as “a part of the world where we have not had a banking presence” because of “past political uncertainties, inflationary policies, leading to currency weakness, lack of skilled labour, poor infrastructure.”Footnote 49 The position was mirrored by Crédit Lyonnais, which remarked that Latin America still figured low in term of priorities, with the exception of Brazil, because “the situation in Argentina [under General Alejandro Lanusse] doesn't allow us to expect greater activity, despite our representative office in Buenos Aires. Chile [under President Salvador Allende] is in the same situation.”Footnote 50

This lack of interest in the region continued until the wave of authoritarianism, the increasing capital flows from oil-producing countries, and stagnant domestic growth converged to push European banks to explore new business opportunities in the region.Footnote 51 During the 1970s, financial flows to Latin America were de facto “bankerized” as the arid years of the 1950s and 1960s gave way to “a virtual torrent of finance.”Footnote 52

The synchronized expansion in the Southern Cone and Brazil was driven by cyclical business opportunities, financial innovations, and sudden capital availability, but deeper political factors were also important. As soon as the new military regimes took power, the attitude of European banks changed dramatically. In 1974, when Lloyds created LBI, Midland Bank created the Midland Bank International Division (MBID) and bought a stake in the Banque Européenne pour l'Amérique Latine.Footnote 53 The increasing interest in the Latin American region also pushed Barclays to split its “Western Hemisphere” line into a North American and a Latin America and Caribbean line. In April 1974 the new governor of the Bank of England, Gordon Richardson—chairman of the merchant bank Schroders from 1965 to 1972 and of the New York–based J. Henry Schroeder Banking Corporation (“Schrobanco”) from 1967 to 1970, who had long been interested in Latin American markets—informed the clearers that he wanted to see “much more activity in Latin America.”Footnote 54

Just before the Argentine financial mission headed by economics minister José Alfredo Martinez de Hoz visited Europe in July 1976, Guy Huntrods, LBI's director of the Latin American Division, wrote a confidential report to the bank's president, chairman, and directors.Footnote 55 He was rather explicit in his praise of the removal of the “Peronista ‘government’ [sic],” the appointment of a “highly qualified economic team of technocrats wedded to the market economy,” and the pursuit of “orthodox financial policies.”Footnote 56 According to Huntrods, the new government had to walk a tightrope “between the need for firmness and the danger of being branded by international opinion as repressive—a charge all too lightly banded around these days and very much a la mode in certain quarters only too ready to pass superficial and prejudiced judgments on Latin American countries where forms of government do not fit into the grey mould of social democracy and mediocrity which is their ideal.”Footnote 57

Huntrods advised LBI's top management in favor of contributing to shoring up the finances of the Argentine regime because the “prospects of economic recovery with a greatly reduced state role and the adoption of free market techniques” would most likely create possibilities for “substantial development of our business and the generation of good profits.” Moreover, he wrote, the Argentine mission was ready to go to the IMF “largely on our advice” for help and to “accept the required disciplines.” LBI had also agreed to roll over US$7 million of public debt maturities for six months, as the bank felt greatly “relieved by the change of government, pleased with the calibre of the economic team and with its general philosophy and objectives.”Footnote 58

Crédit Lyonnais rapidly shifted its priorities and recognized Brazil and Argentina as its top priorities in Latin America.Footnote 59 In its new strategic program, the bank pointed out that Argentina had now managed to reestablish its financial equilibrium and the country “had again become open to international investments.”Footnote 60 Regarding Latin America, the region was now “one of the strong points of Crédit Lyonnais” because of “its rapid economic recovery and the opportunities for economic growth.”Footnote 61 In the 1979–82 program, Brazil figured as the top regional priority, followed by Chile and Argentina, as Argentina's external financial health was “excellent” and Chile had reestablished internal stability and “re-conquered the esteem of the international financial community.”Footnote 62

Visiting Argentina and Brazil in March 1980, Yves Laulan, chief economist at Société Générale, was favorably impressed by the successful and “implacable” war on “left-wing terror” and found the safety in the streets of Buenos Aires to be “remarkable.”Footnote 63 Overall, the number of foreign banks in Argentina increased from eighteen to thirty-three between 1978 and 1982.Footnote 64

External capital also played an important role in legitimizing the economic programs of authoritarian rulers, as in 1978 when the governor of Chile's Central Bank obtained in London a US$210 million loan from a consortium of forty-nine banks. The loan had been carefully planned during a visit to London by the president of the Central Bank of Chile, Alvaro Bardon, in April 1977. When the British embassy in Santiago called on Bardon, he informed the embassy that he would be traveling to Europe and would take the opportunity to visit London. Despite being “a little coy about the reason for his visit,” Bardon implied that he “would be seeking medium or long term loans from European banks for the Central Bank.” He indicated that “there were a couple of British banks which were interested in making medium term money available to the Chilean Central Bank. Needless to say he did not mention their names.”Footnote 65 This last sentence shows that lending to certain regimes was perceived as a risky business that could create problems for the lenders and borrowers. The official from the British embassy remarked that from what he had seen of recent activity in the country, he had “little doubt” that the banks concerned would be LBI and Anthony Gibbs, a merchant bank.Footnote 66 Chile had asked for US$150 million but the loan was oversubscribed multiple times. Enrique Tassara, head of foreign finance at Banco Central de Chile, reported to the American embassy that oversubscription was a “recognition” by international finance of Chile's payment record and an “expression of confidence” in Chilean development.Footnote 67 The new regime in Chile met with public outcry in the United Kingdom (e.g., the Chile Solidarity Campaign) but several actors clearly stated their appreciation for the regime of Augusto Pinochet behind closed doors.Footnote 68 An internal document of the Bank of England reported that the Allende regime had left behind it a “legacy of chaos,” while with the new regime, people were “visibly happy” and “streets are clean” with no signs of “passive resistance, labour absenteeism, social unrest or general lack of co-operation.” The Bank of England went further, overtly criticizing the policy of the new Labour government led by Harold Wilson against the Pinochet regime, arguing that “H.M.G.'s [Her Majesty's Government's] decision [to suspend U.K. aid to Chile] has caused substantial hurt and anger in Chile and the goodwill which the U.K. previously enjoyed has not surprisingly been lost—which could well have adverse repercussions on our commercial relations.”Footnote 69

Among the British banks, LBI quickly emerged as the most active player in the Southern Cone and Brazil. At the end of 1975, just one year after its creation, LBI was already the most active bank in Chile, accounting for £12 million of a total £17 million claims, £89 million claims on Brazil out of £309 million, and £40 million of £140 million total claims toward Argentina. National Westminster was the second most active British bank in Latin America, with claims on Brazil and Argentina totaling £53 million and £34 million, respectively.Footnote 70

In the second half of the 1970s, the European banking presence was also influenced by political changes in the United States. In May 1977 President Jimmy Carter made a famous speech on U.S. foreign policy in which he criticized the “inordinate fear of communism which once led us to embrace any dictator who joined us in that fear” and reaffirmed “America's commitment to human rights as a fundamental tenet of our foreign policy.”Footnote 71 The measures implemented by the Carter administration ultimately strengthened the role of European exporters and, consequently, commercial banks. While outstanding claims by U.S. banks on major developing country borrowers grew by 17 percent per year between 1976 and 1979, those of non-U.S. banks grew by more than 42 percent.Footnote 72 The retrenchment of EXIM Bank activities under Stephen M. DuBrul Jr. further amplified the declining American role in the region.Footnote 73

While banks were eager lenders, military regimes were eager borrowers and acted quickly to attract foreign capital. The Argentine government passed several laws to attract foreign investments and liberalize the financial system, most notable among them the Ley de Inversiones Extranjeras of August 1976 and the Reforma Financiera in June 1977.Footnote 74 Similar legislations were passed in Chile to alleviate the financial strains imposed by the oil crisis of 1973.Footnote 75 Chile liberalized and, then, completely privatized the domestic financial sector by the end of 1978. Interest rates were liberalized starting from 1974 and the capital account of the balance of payments in June 1979, which resulted in a massive appreciation of the peso.

International trade in Chile was liberalized in 1976–1977 as tariffs were sharply reduced.Footnote 76 Trade liberalizations in Argentina were on a much more modest scale and the results were almost invisible at the time of democratic transition. Brazil was on an autonomous economic trajectory starting with the Plano de Ação Integrada do Governo (PAEG) implemented between 1964 and 1967 by the Castelo Branco administration. Although equally interested in attracting foreign capital to finance the economic miracle, Brazilian officials never questioned the central role that the state had to play in economic matters as the “great regulatory and normative agent in socio-economic matters.”Footnote 77

Argentina became the jewel in the crown for LBI, which quickly emerged as one of the three largest lenders to the regime.Footnote 78 The chairman of LBI, Sir Jeremy Morse, reported to the board that the “military government has mastered open terrorism at some cost in human rights. . . . [T]heir civilian Finance Minister [Martinez de Hoz] . . . has freed the economy.”Footnote 79 The stable political outlook and the rosier economic scenario enabled LBI to plan several investments in the military-led country. The Central Bank allowed LBI to open five new branches, and in a private meeting in Washington, D.C., Central Bank governor Adolfo Diz personally congratulated the chairman of LBI for the good results and promised to expedite Central Bank approval of the bank's accounts. With regard to Brazil, Morse remarked that “there is a constant flow of requests for Eurocurrency loans, mainly from the Brazilian public sector.”Footnote 80

Looking at the composition of banking exposure to military-led countries, it is important to note that most of the borrowing was incurred by government-owned companies, except in Chile, where private borrowers largely outranked public ones.Footnote 81

Risk Assessment and Corporate Structures

The lending boom had many justifications, and establishing a pecking order is beyond the scope of this paper. Undoubtedly, rudimentary risk-assessment procedures and a lack of homogeneity in banking statistics contributed greatly to pushing banks toward excessive risk-taking and myopic decisions. In a memorandum about the meeting of the IMF task force on the recycling problem, M. D. McWilliam of Standard Chartered Bank, a leading British-based bank, clearly stated that “the statistical picture is not at all clear cut, and different acceptable conventions seem to apply in different national banking systems.” The French banks felt “very little concern for capital adequacy and are quite happy to see their balance sheets expanding.” Concerning country risk evaluation, bank practices varied widely. McWilliam remarked that “The French seemed to be the most relaxed on the matter. Citibank was inclined to see country exposure in the context of total risk assets, as compared with . . . Morgan Guaranty and Swiss Bank Corporation who test country exposure against their total international exposure. . . . Most banks seem to lump together short and medium term exposure.”Footnote 82 The lack of uniformity in assessing the risk of individual countries seems to confirm what Stephany Griffith-Jones wrote several years ago: “The task of quantifying the elements which determine bank's assessment of a ‘country's creditworthiness’ seems an almost impossible one.”Footnote 83

Varying risk-assessment practices reflected different corporate and decision-making structures. As we have anticipated, most British commercial banks opted for the creation, or transformation, of separate legal entities to conduct their business while the largest French banks kept their international activities under one roof. At Société Générale, for example, the international business was conducted through the Direction de l’Étranger (Foreign Department) with its own management committee. The Foreign Department was in charge not only of all the international activities of the bank but also of all the activities on the Eurodollar market, namely Eurobond and Euroloans that were regrouped under one unified Finance Division after previously being managed by two separate ones. At Société Générale the man in charge of the Foreign Department was Viénot himself, who reported directly to the chairman of the bank, Maurice Lauré. British banks often operated on international markets through ad hoc subsidiaries like LBI and BBI with their own independent management and corporate structures. The margins of freedom, and error, were larger than in the French case because the decision-making and lending process was highly decentralized. LBI, by far the largest European bank in South America, had its top management—namely, Huntrods and his team of around fifteen—not on the ground but in London instead. Huntrods visited Argentina twice a year on average, while Argentina's general manager visited London once a year. As a former general manager of LBI recalls, “We were left alone with a lot of autonomy.”Footnote 84 This geographical distance proved to be a source of substantial agency problems, as the task of supervising a workforce of around 4,500 people proved to pose quite a challenge to the few colleagues in London. By June 1980, the Latin American Division at LBI was “made aware that a number of serious bad debts were being incurred by various branches in Argentina.” Internal investigations revealed that the most important factors leading to such losses were the poor macroeconomic context as well as “errors of judgement and poor credit assessment.” The high degree of freedom of high- and mid-level managers was also recognized by Huntrods, who clearly stated in front of the chairman's committee that the general manager in Buenos Aires had failed to “discipline managers who, even after warning, granted unauthorized facilities.”Footnote 85

Did the structures of decision-making and credit assessment change over time? The international financial community was of course aware of the increasing levels of debt in the developing world. The first discussions about developing countries’ debt had started in the early 1970s, when the World Bank published a study on “the external debt of developing countries” in August 1971.Footnote 86 The situation stabilized in the subsequent years as commodity prices rose and the recycling process seemed to function rather effectively. After the second oil crisis, interest in crisis scenarios picked up again. By the beginning of 1980, the Bank of England had started working on possible crisis scenarios with a series of documents aptly titled “Apocalypse Now.”Footnote 87 The documents dealt with the consequences of a default by a “major borrower” such as Brazil or Mexico. Those two countries became prominent topics of discussion in international financial circles after the second oil crisis, in 1979 and 1980, that put further strain on the global economy and on developing countries especially. As the pressure on their balance of payments intensified, large borrowing countries such as Brazil intensified their efforts to attract new capital, adopting a twofold strategy: on the one side, they invited foreign bankers to visit their country, and on the other, planning and finance ministers from Latin America's largest borrowing countries intensified their visits to Western capitals to secure larger and larger loans. As the title of the Bank of England's document would suggest, their efforts were sometimes met with skepticism. In the 1980s, a Foreign Office official reported to the British embassy in Brasilia that the atmosphere during the visit to New York by the Brazilian minister of planning, Antonio Delfim Netto, was “chilly” and “not enthusiastically received” as New York bankers “were not inclined to believe his figures” while “European bankers were ready to lend but not at present spreads.”Footnote 88 In this context of growing incertitude, LBI and Huntrods proved to be fairly optimistic compared with their peers. Richard Ewbank of the Bank of England reported that during a conversation with Huntrods at a reception organized by the Euro-Latinamerican Bank, Huntrods was “inclined to take a fairly robust view about the Brazilian situation, feeling, as they do in view of the mere size of the external debt, that there is no alternative to staying with Brazil.”Footnote 89 On the same occasion, Barclays representatives remarked that they would be staying with Brazil but keeping “a close watch” on the situation by continuing to make funds available to existing customers, or in support of British export credits, but would limit participation in syndicated Euroloans.Footnote 90 Ultimately, the doubts about Brazil did not result in a substantial decrease in lending and this puzzled officials at the Bank of England, who wondered “how Brazil has managed to keep going despite the fears that were being freely expressed some 12 to 18 months ago.”Footnote 91 An internal report ultimately found that the main reasons for the Brazilians’ “success” resided in positive results on the exports side and, especially, in the “flexibility on the part of the Brazilians in offering more generous terms to the commercial banks.”Footnote 92 Brazil had agreed to raise margins above the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) from 0.875 percent to 2.25 percent in just a year and had reduced periods to final maturity to eight years from ten to twelve years (like the US$1.2 billion jumbo loan issued in November 1979).

Ultimately, it is not possible to argue that banks engaged in any kind of learning process despite frequent interactions with government officials, central bankers, and international organizations such as the IMF. Bankers seemed to be suffering from tunnel vision, a medical condition in which one can see only what is directly in front of them. In March 1980, Yves Laulan of the Economic Department of Société Générale was invited to visit Brazil accompanied by Marcilio Marques Moreira, vice president of the financial conglomerate Unibanco, to analyze the economic situation of the country and promote the bank's activities in the region. Laulan remarked that “there's a lot of talking about Brazil's level of indebtedness and rightly so. Its level will increase from 52 billion at the end of 1974 to 60–65 billion at the end of this year [1980]. . . . Despite that, it must not be forgotten that Brazil is a continent-country. Comparing its indebtedness to that of Israel or South Africa risks of being meaningless.” Laulan was particularly impressed by the progress since his previous visit three years earlier and by the country's economic potential. He also praised the “quality of men with a high level of intellectual sophistication, an entrepreneurial spirit and a remarkable confidence in the future.”Footnote 93 The main preoccupation of commercial bankers up to the 1982 crisis remained the smooth functioning of the recycling of petrodollars in the absence of official channels to transfer capital from surplus to deficit countries. This is confirmed by Laulan, who clearly stated, “I am convinced, like may others, that the recycling problem stands the risk of being an exceedingly difficult task [to manage]. If we can't find suitable outlets, several millions of dollars will have to be placed in 1980 and 1981 at poor conditions. Outlets in Europe and the US are drying up. . . . [O]n the contrary, Brazil (and Argentina) have very elastic absorption capacities for capital.”Footnote 94

Steel, Politics, and Armaments

When General Ernesto Beckmann Geisel paid the first visit by a Brazilian head of state to the United Kingdom, between May 4 and 7, 1976, he was greeted personally by the queen and several other members of the British royal family before being escorted to Buckingham Palace on a golden carriage pulled by six white horses. On the streets, several hundreds of protestors showed banners denouncing military rule, “trading with fascists,” and mass torture.

During the state visit an entire morning was set aside at Buckingham Palace, “at the Brazilian Embassy's request,” for a meeting between the London financial community, headed by the governor of the Bank of England, and the Brazilian economic establishment, which included Geisel himself, the foreign and finance ministers, the president of the Central Bank, the president of the Banco do Brasil, and the president of the Development Bank.Footnote 95 The meeting had been carefully planned. A few days before the state visit, the Comptroller of the Lord Chamberlain's Office had written to all the invited bankers that “President Geisel . . . attaches great importance to the talks and discussions . . . not only with Her Majesty's Ministers . . . but also with industrialists, bankers and businessmen.”Footnote 96

As Frieden rightly argued several decades ago in the case of Argentina, industrial investments in the steel and armament industry, energy, and transportation figured as the top priorities for military regimes. Brazil was borrowing at an impressive rate for a variety of reasons and projects, from building its own arms industry to financing its nuclear ambitions in the context of its Second National Development Plan, which inaugurated the debt-cum-growth strategy.Footnote 97 During Geisel's visit, the financing of the US$500 million Açominas steel plant in the southeastern region of Minas Gerais and the electrification of the Belo Horizonte-Itutinga-Volta Redonda railway line (also known as Ferrovia do Aço, or Steel Railway) were the largest projects discussed. The electrification was of great importance for the good functioning of the whole project, as diesel engines were dangerous on many parts of the track where long tunnels existed.Footnote 98 Both projects were essential for the regime and interconnected. Açominas was to become one of the largest and more modern steel plants in Latin America while the Steel Railway was to connect the mining region of Minas Gerais to the metropolises of Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

The Steel Railway involved a £175 million financing to be complemented with a credit in U.S. dollars on a one-to-one ratio. The Brazilians insisted that a dollar loan was a common practice accepted by all other Western counterparts. German banks, the Brazilian delegation argued, had already agreed to provide US$700 million in support of nuclear power plants. Midland Bank was well aware of the political implications of the loan, remarking that the loan “was not acceptable judged on normal commercial criteria” but acknowledging that “a number of ‘political’ considerations were involved.”Footnote 99 Moreover, the Brazilians made it very clear that “the placing of large export contracts with a foreign country is dependent upon banks in that country providing supplementary Euro-currency lending.”Footnote 100 None of the clearing banks was particularly enthusiastic to accept a trade-off between export credit finance and Euroloan participation, but Rothschild, the bank in charge of setting up the financing, stressed the “political aspects of the deal, both as far as President Geisel's position in Brazil was concerned and . . . the U.K. need for exports.”Footnote 101 Ultimately, the Treasury decided to provide a further US$25 million through the Export Credits Guarantee Department (ECGD) as an additional and separate loan to the banks and a deal was finally reached. Huntrods insisted that the decision was “only being made in the national interest.”Footnote 102 The Steel Railway ultimately took four thousand days to be only partially completed, instead of the one thousand days promised by the regime, and cost US$4 billion. Currently it is largely abandoned.

Similar political considerations were involved in the second large project, the Açominas steel plant in Minas Gerais. After the memorandum of understanding was signed during Geisel's visit, long negotiations between British bankers and Brazilian officials followed. Its historical ties to the Latin American region managed to put LBI in a profitable but risky position as its presence was often used to justify its involvement in large projects. In December 1976, talking to Morse and Huntrods, the Brazilian ambassador to the United Kingdom insisted that “as the only clearer with a direct presence in Brazil, Lloyds should give a lead in helping to arrange eurocurrency finance for projects of national importance such as Açominas.”Footnote 103 As in the previous case, banks were not always eager lenders when they felt that “political” investments were too risky. Huntrods and Morse told the ambassador that LBI already had a very important exposure toward Brazil and had to prioritize projects in which its own customers were involved. Huntrods sensed that the ambassador was not willing to accept such justifications and that it seemed like “there is an overriding obligation upon us to be in the forefront of this government's pet projects.”Footnote 104

Overall, Geisel's visit had proved to be a political success for the regime and “beyond expectations on the economic front.”Footnote 105 Geisel was particularly appreciative of the “number one red carpet treatment” and of the “‘smoke screen’ that HMG erected around protest demonstrations (e.g., drowning them out with noise from police motorcycle [sic] on one occasion).”Footnote 106 Human rights violations were mentioned briefly, “to accommodate the Labor Party's left wing,” but quickly dropped when the general deemed the topic “unfit for discussions.”Footnote 107 Appreciation for the regime is palpable in the internal documents of commercial banks. In a memorandum to the LBI chairman, Huntrods remarked, “It is only twelve years since the Military took over and in that time they have dealt not only with the extremely serious economic and financial situation they inherited, but turned Brazil from always being the country of the future into that of the present, and they have implanted a self confidence and thrusting mentality which did not previously exist. By the skillful employment of technocrats in key ministerial positions, by the creation of a climate of confidence overseas, by the establishment of the country's creditworthiness and a clear move away from the irresponsible attitude of the former civilian governments, the military have achieved an enormous and far-reaching practical and psychological change.”Footnote 108

Several recurring elements can be found in these internal documents. The political stability, the appointment of technocrats, and a renewed probusiness climate are some of the keys to understanding the positive attitude of European bankers toward military regimes. Moral judgments were mostly absent from the bankers’ discourse or, at best, were left aside. Referring to the Brazilian regime, Huntrods remarked, “Whatever moral judgments one may make about the nature of the regime, the fact is that it does have the muscle to impose its economic solutions upon the populous [sic] and therefore to come up with the type of stabilisation measures which would unlock the coffers of the international lending institutions.”Footnote 109 These views were shared by the IMF. Referring to the IMF's attitude toward Chile, Kedar argues that “the IMF did not let any concerns over the repression, torture and disappearances of thousands of Chileans and foreign citizens obstruct its (limited) cooperation with the Chicagos [Chicago boys].”Footnote 110 Similar behavior in different geographical contexts reflects a consistent attitude against considering criteria other than strictly commercial ones when dealing with foreign governments. For example, when Midland Bank was targeted by activist groups for its involvement in South Africa, the chairman argued, “In our lending, we should follow normal banking principles and . . . we should not allow ourselves to be influenced either by our own personal opinions, or by opinions expressed to us by others, about a borrower's conduct outside the commercial field.”Footnote 111 The concept of corporate social responsibility was still a chimera.

Moving beyond existing narratives positing a unidirectional responsibility in the lost decade of the 1980s, the archival evidence presented above shows that the relationship between European banks and military juntas was more complex and must be interpreted as both a bidirectional and multilevel phenomenon where both parties played an active role in establishing contacts.Footnote 112 Official state visits or interventions on both sides of the Atlantic were important, often critical, sources of contacts between military juntas and European banks. French president Giscard d'Estaing paid a visit to Geisel in October 1978 accompanied by four ministers, pushing Argentine newspaper Clarín to ask “Que Busca Francia en Brasil? [What is France looking for in Brazil?]”Footnote 113 German chancellor Helmut Schmidt visited several Latin American countries in April 1979. King Juan Carlos of Spain paid a visit to Argentina in November 1978 and was bitterly criticized at a time when Spain was transitioning toward democracy. With regard to the destination of loans, the largest borrowers were by far state-owned enterprises and development banks, especially in Brazil and Argentina, which were the two largest borrowers in South America, while in Chile private debt represented the majority of total debt. A thorough analysis of individual borrowers in Southern Cone countries and Brazil is far beyond the scope of the present article, but if we take 1979, the year of the second oil crisis, as an example we see that among the biggest borrowers in Brazil were the Brazilian state oil company, Petrobras, with a loan of DM125 million, Eletrobras (US$400 million), the National Superintendence of the Merchant Marine (US$250 million), the Itaipu Dam (US$160 million), the state development bank, BNDES (US$350 million), and the federal government of Brazil, with a “jumbo” loan of US$1.2 billion.Footnote 114

That same year, Argentina borrowed US$250 million in favor of YPF, the state oil company, the state development bank (BANADE) borrowed DM100 million, the Banco Nacional US$50 million, the Argentine Republic DM150 million and US$35 million, and the Provincial Bank of Buenos Aires US$30 million. These numbers for Argentina aptly describe the general pattern of indebtedness of the dictatorship, as all of these borrowers figured among the twenty largest borrowers—with YPF in second place after the Central Bank, BANADE in fourth, and the Provincial Bank of Buenos Aires in sixteenth position.Footnote 115

In Chile the loans helped the regime to reinforce the business groups that had supported its rise into power. Loans were often channeled through the state agency CORFO (Chilean Development Corporation, led between 1980 and 1983 by Pinochet's son-in-law Julio Ponce Lerou) at preferential rates to the most politically involved business groups, such as Cruzat-Larrain, Vial, Matte, and Edwards. The money was then used to buy newly privatized banks and/or nonfinancial firms. As Carlos Diaz-Alejandro argues, “The two largest business groups in Chile by late 1982 controlled the principal insurance companies, mutual funds, brokerage houses, the largest private company pension funds and the two largest private commercial banks. . . . By late 1982 many banks had lent one quarter or more of their resources to affiliates.”Footnote 116 Lending to affiliates, a practice known as auto-prestamos, rapidly increased private-sector indebtedness, which increased from 42 percent to 70 percent of GDP between 1980 and 1982.Footnote 117 Both Grupo Vial and Cruzat-Larrain would be dissolved during the 1981–1982 economic crisis.Footnote 118

Argentina actively sought to bolster ties with Europe through its Cambridge-educated economics minister, Martinez de Hoz, who served as a “goodwill ambassador” of the regime. Between 1976 and 1980, Martinez de Hoz visited the United Kingdom four times, meeting with key government officials despite the first two visits, in 1976 and 1977, being private. As anticipated, Martinez de Hoz first visited the United Kingdom just a few months after the military takeover, on July 19 and 20, 1976. The visit involved a European tour across Switzerland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, the United Kingdom, Spain, and Italy. During the two days spent in London, the Argentine delegation (composed of Martinez de Hoz, Adolfo Diz, and Francisco Soldati of the Central Bank) met with, among others, the Treasury, the Department of Trade, the Bank of England, and the ECGD, on the public side, and LBI on the private side. The chairman of LBI and Baring Brothers hosted a dinner party in honor of the Argentine mission at the Brooks Club in St. James on the final day of the trip. Minister Martinez de Hoz's first venture abroad turned out to be a resounding success for the regime. The overall goal of the tour had been to put together a contribution of US$300 or $400 million of an overall package of US$1.2 billion in support of the Argentine balance of payments. Once the tour was over, D. S. Keeling of the Latin American Department of the Foreign Office reported that “if the figures are accurate it looks as if Dr Martinez de Hoz's European tour was pretty successful.”Footnote 119 British banks had indeed agreed to lend the Argentine regime a total of US$60 million. LBI led the pack, with US$15 million, followed by Barclays and Midland with US$10 million each.Footnote 120 The September 1976 issue of financial magazine Euromoney featured a cartoon of Martinez de Hoz on its front cover above the words “Argentina takes the recovery trail.” The accompanying article remarked that “although the minister's course was not entirely smooth, he did succeed in re-establishing an essential part of Argentina's image: credibility.”Footnote 121

As its new Conservative government came to power, the United Kingdom's relationship with Southern Cone regimes became closer.Footnote 122 Martinez de Hoz finally received an official invitation to the United Kingdom in the first months of 1980, when all of Argentina's human rights violations were well known. The Foreign Office wrote that the regime had “suppressed the violence with characteristic ruthlessness” and that “many people were killed, [and] many more have disappeared.”Footnote 123 While this was happening, Martinez de Hoz was described as a friend of the United Kingdom: “brought up by an English nanny and [having] learned to speak English before Spanish”; his credentials as a true friend of the United Kingdom were further reinforced by his “passion for shooting” and the fact that he “still buys his guns and has his trophies stuffed in London.”Footnote 124

In 1980, R. M. J. Lyne of the Foreign Office wrote to Michael Alexander, Margaret Thatcher's diplomatic private secretary, to arrange a meeting between Martinez de Hoz and the prime minister. Lyne described Martinez de Hoz as “very well disposed towards the UK” and noted that “we are unlikely . . . to enjoy another such asset in our relations with Argentina as the Minister now represents.”Footnote 125 On June 5, they met in Thatcher's office at the House of Commons. Martinez de Hoz presented his latest economic measures and said that they “were very similar to those being pursued by the Prime Minister.” At the end of the meeting, he conveyed General Jorge Rafael Videla's greetings and reassured the prime minister that a change of minister or head of state in Argentina would not “presage any change of policy.”Footnote 126

European governments had a crucial role in negotiating contracts with Latin American regimes, using their influence to strike deals for their companies and banks. Often these contracts involved large industrial projects; at other times, infrastructural investments such as the abandoned Ferrovia do Aço or the still largely unpaved Trans-Amazonian Highway. Another kind of deal that came to be especially cherished by European governments involved the export of armaments. In the depressed economic scenario of the 1970s, “economic considerations play[ed] an important role in arms sales” and governments were willing to sell “almost any weapon to anybody.”Footnote 127 These arms were acquired with the help of “financial packages” that European banks developed with the assistance of European governments and exporting agencies, such as Coface of France, ECGD of the United Kingdom, and Hermes of West Germany.Footnote 128

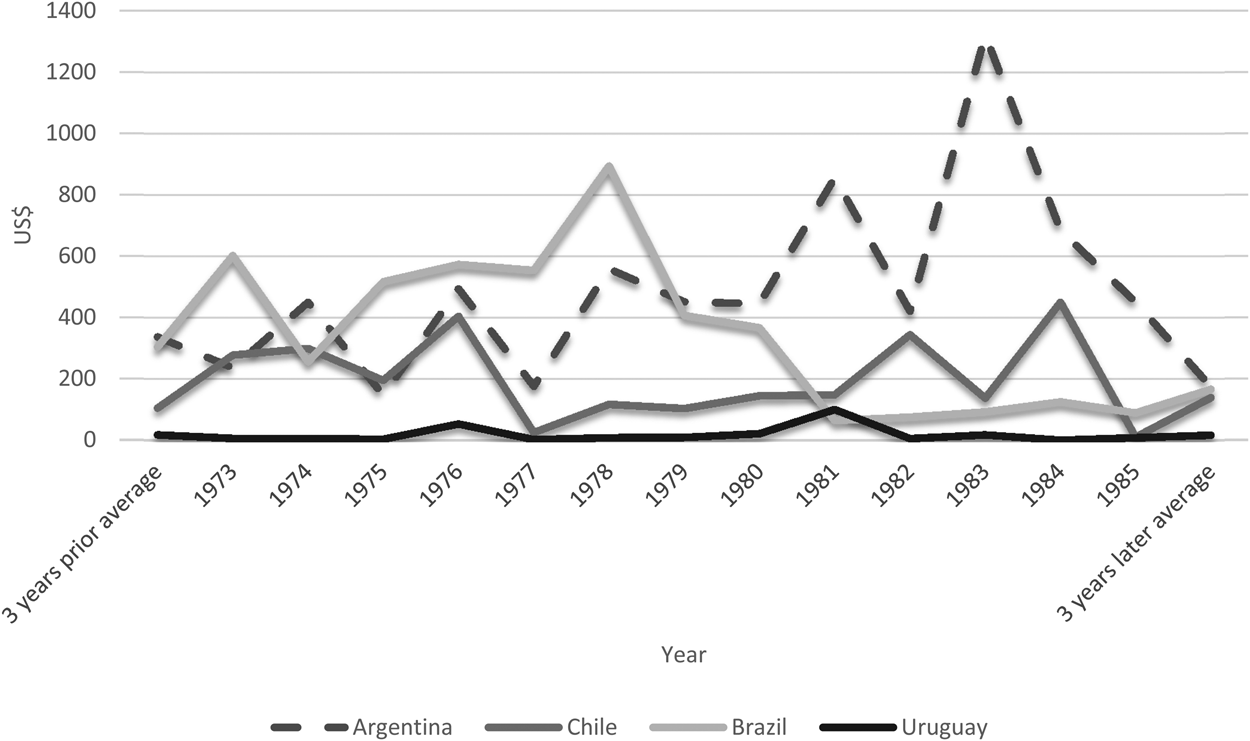

Data are difficult to gather for obvious reasons; for the purpose of this article, we rely on the data provided by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). Figure 1 shows a constant increase in arms exports to the Southern Cone and Brazil, especially remarkable in the case of Argentina, with a peak in 1983 of more than US$1.3 billion following the signing of several agreements with Western countries in the second half of the 1970s.Footnote 129 It is not surprising, then, that the Argentine Navy figured in sixth position among Argentina's twenty largest borrowers, with a total debt of more than US$2 billion, and the Argentine Army figured in twelfth position, with a total debt of more than US$700 million.Footnote 130 Neighboring countries show a less clear-cut path: Chile reached a low point in 1977 and then started to rearm quickly once the U.S. embargo was offset by increased domestic production; imports from Europe, Israel, South Africa increased substantially as the Beagle Channel conflict hastened after the Arbitration Award drafted by the International Court of Justice was confirmed by the British Crown.Footnote 131 With regard to European arms imports, General Pinochet told the U.S. ambassador, David H. Popper, that the United States had “closed several doors [to Chile]” and “though it had been costly, Chile had found other sources for arms.”Footnote 132

Figure 1. Arms imports (US$ millions, constant 1990 prices). (Source: SIPRI Arms Transfers Database, https://www.sipri.org/databases/armstransfers.)

Arms exports to Brazil peaked in 1978 and then started to decrease, possibly reflecting the new status of Brazil as an emerging arms producer and exporter. By 1982, 60 percent of the military equipment used by its armed forces was produced domestically and accounted for 45 percent of Third World total arms exports, making Brazil the eighth-largest arms exporter in the world.Footnote 133 Europe came to play a dominant role in Latin America as U.S. humanitarian concerns led to a drastic decrease in American supplies to the region. The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in July 1978 concluded that “if US restraints continue to be applied unilaterally, West European suppliers can provide a reasonable alternative to US supplies. . . . None of these countries is expected to turn down orders, which are needed for jobs, export earnings, and lowered unit costs on equipment produced for their own services.”Footnote 134

The CIA was right. Arms supplies from the United States decreased from US$240 million to US$130 million between 1974 and early 1978, while western European supplies increased from US$265 million to more than US$1 billion.Footnote 135 As the American embassy in Buenos Aires aptly summarized, “Argentine relations with Western Europe are politically cool, due to human rights, but economically robust and growing.”Footnote 136 This state of things would last until August 1982, when Mexico declared its inability to repay its foreign debt. The declaration ignited a regionalization syndrome that affected the whole developing world but particularly the Latin American region.Footnote 137 As international capital dried up, the regional economy started to crumble and austerity measures had to be implemented. Increasingly, the legitimacy of the military came to be questioned by popular movements. As economist and future Peruvian president Pedro Pablo Kuckzynski argued in 1984, “The continuation of austerity, necessary from a financial point of view, may not be doable in countries without strong political traditions and institutions.”Footnote 138 Ultimately, the lack of legitimacy did not allow the military juntas to implement the harsh austerity measures imposed by the international financial community nor to endure the social costs associated with them. Mass protests and power transition ensued.Footnote 139

Conclusion

The interactions between commercial banks, European governments, and military dictators during the Eurodollar lending boom of the 1970s have received limited attention from business historians thus far. While contemporary political scientists and economists have identified the importance of these interactions, this article relies on a wide set of recently disclosed archival evidence to illustrate how the military regimes of this era were able to deploy multinational bank lending to sustain themselves.

Timid attempts to enter South American markets began in the late 1960s as the Eurodollar market and increased domestic competition forced European banks to reconsider their conservative stance on international presence. Although these early efforts resulted in the creation of new international subsidiaries, such as BBI and LBI, and in the reshaping of corporate structures, they did not radically modify the geographic priorities of European banks. As we have illustrated, real or perceived political and monetary instability contributed to stifling new ventures. The article suggests that this situation changed in the early 1970s as increasing capital flows from oil-producing countries, stagnant domestic growth, and the perceived political stability of new authoritarian governments committed to orthodox monetary policies pushed foreign banks to expand decisively in the Southern Cone and Brazil.

The change in attitudes was rapid and unambiguous; in Argentina, for example, the number of foreign banks almost doubled between 1978 and 1982, from eighteen to thirty-three. Banks and military regimes began establishing solid business relations resulting in the lending of vast sums of money directly to governments and government-owned companies. Internal documents show that foreign bankers were not always the rational actors assumed by economic theories; instead, they saw military regimes through their own ideological lens, superimposing their own narratives on these countries and ignoring conflicting evidence. In particular, the scale of banking involvement after the military takeover seems to confirm that European commercial banks saw the political stability, the appointment of technocrats, and the orthodox economic measures implemented by military juntas in largely favorable terms.

While in European capitals military dictators were publicly criticized at times, business continued as usual behind closed doors despite ample evidence of forced disappearances and political killings. As the Steel Railway project and the Açominas steel plant well illustrate, European governments used domestic banks to devise attractive financial packages with which to lure South American customers. The relationship grew more symbiotic throughout the 1970s, thereby putting a definitive end to the Bretton Woods years of controlled capital flows.

Archival evidence also allows us to move beyond existing narratives positing a unidirectional responsibility in the lending boom of the 1970s by showing that the relations between lenders and borrowers were bidirectional and multileveled. Borrowing countries were not simply passive clients but active participants in the recycling of petrodollars. Military governments sought foreign capital by visiting European countries and inviting bankers to South America. Once foreign capital entered the countries, it was used for a wide variety of purposes according to the priorities of each regime. In Brazil, the military followed a developmentalist economic policy: foreign capital was invested mostly in infrastructural projects, the energy sector, and heavy industry, including arms production. In Argentina, the regime used borrowed money to sustain the exchange rate, import huge quantities of weapons, and invest in the oil and energy sector. The Pinochet regime, in contrast, channeled foreign capital through the state agency CORFO to the business groups that had supported the rise of the regime. These crucial years left a contrasting legacy for South American countries and global banks. A decade of unbridled petrodollar recycling allowed commercial banks from Europe, the United States, and Japan to enter the global stage and accelerate their transformation from mostly domestic institutions into global players able to compete for deposits and sell their services across the world.

After a short interruption resulting from the 1982 debt crisis, international financial institutions continued to expand in South America as the end of state-led development and the wave of privatizations and liberalizations provided ample opportunities for growth. In particular, Spanish banks saw South American countries as the ideal territory in which to expand their activities and become global players. With the possible exception of Brazil, foreign banks now dominate all major domestic markets in the region; in Chile and Argentina, foreign banks control almost half of all deposits.

While the 1982 crisis paved the way to one of the greatest waves of democratization in modern history, it also brought prolonged misery to South American countries because of the austerity measures required by international creditors. Moreover, countries in South America continued to suffer from persistent dependency on commodity price cycles and foreign (sometimes predatory) capital, clientelism, corruption, and high levels of inequality that have gradually weakened the region's democratic foundations. As authoritarian tendencies appear to make a comeback across the region, corporations should draw lessons from past behaviors and be aware not only of the inextricable link between economic targets and political constraints but also of the long-term consequences of their activities.