‘Does trouvère melody express poetic meaning?’, asked Hans Tischler nearly three decades ago.Footnote 1 Scholars of trouvère song have largely, until recently, avoided this question and, rather than exploring the meaning of melody in trouvère song, have tended to focus on questions of manuscript transmission, scribal practice and historical context.Footnote 2 By examining the language used by trouvères in their songs, it may be possible to understand – at least in a preliminary fashion – the meanings that could be associated with melody in thirteenth-century monophony. Trouvères used several words to describe their compositional acts, two of which deserve closer attention for the light that they shed on the meaning of melody, and in particular the meaning of melodic structure: trouver (to find) and partir (to divide). Rooted in medieval discourses of rhetoric, literary composition and cognition, the concepts of trouver and partir open a window onto the approaches that trouvères took to creating their songs. In this study, I argue that by paying close attention to the relationships between the words and melodic structures employed by trouvères, we may gain an insight into their creative processes and the meanings that such compositional acts were felt to have among trouvères and their contemporaries. A particularly rich source for understanding meaning in monophonic song is the jeu-parti, a genre of trouvère song in which two trouvères debate a love question by exchanging stanzas.Footnote 3 Because trouvères responded to one another (or at least appear to) in jeux-partis, the genre offers a snapshot of processes of musical creation and reception and the social value of inventio and divisio played out through song.

When discussing the structure of vernacular monophonic song, scholars have tended to focus on categorisation rather than on the structure’s meaning, normally recording particular parameters of text and melody. On the largest scale, the same melody may be set to several strophes in a song (isostrophic), or different strophes could have different melodies (heterostrophic). This was often aligned to genre, with, for example, grand chant as isostrophic and the lai as heterostrophic.Footnote 4 At the level of the strophe, a melody could be structured by the repetition of significant portions that corresponded to poetic lines, as in the pedes-cum-cauda form (AAB), or it could be through-composed. The structure of song texts can be described in terms of the number of lines in a strophe, the number of syllables per line (isometric or heterometric), the use of oxytonic and paroxytonic line endings, the scheme of rhyme words at the end of lines, the use of caesuras and the reuse of rhyme sounds from strophe to strophe. The inclusion and placement of refrains also feature in descriptions of form.

Our knowledge and methods for studying the structure of medieval song have been shaped significantly by the work of Friedrich Gennrich. Before his monumental study, Grundriss einer Formenlehre (published in 1932), scholars had, according to Gennrich, insufficiently documented the ways in which poetic and, especially, musical forms were constructed in medieval song.Footnote 5 Gennrich considered the end of the eleventh century until the end of the thirteenth century to be a period that witnessed the greatest variety and richness of musico-poetic form ever.Footnote 6 Writing with explicitly biological terminology (Gennrich refers to song strophes as organisms), he understood all surviving medieval songs to belong to one of four species: the litany, the rondeau, the sequence and the hymn. To taxonomise songs in this way, Gennrich devised a graphical representation for the different interlocking structures of a song, showing rhyme scheme, syllable count and the repetition of melodic segments (which correspond either to the whole or to parts of individual poetic lines). This method of representing musico-poetic structure remains in use in scholarship today, albeit with different symbols.Footnote 7

The drive to taxonomise that can be seen in Gennrich’s work is also found in the publications of other nineteenth- and twentieth-century scholars. Gaston Raynaud’s catalogue of trouvère song (1884) is ordered by the end-rhyme of the first line of each song; Hans Spanke’s reworking of the catalogue in 1955 added to each song the number of syllables per line, rhyme scheme and melodic scheme, as well as providing information on songs that shared the same poetic or musico-poetic structure.Footnote 8 One of the applications of Gennrich’s method, as taken up by Spanke (and expanded later by Ulrich Mölk and Friedrich Wolfzettel), was the identification of a song as a contrafact of or model for another, which was particularly appealing for scholars of Middle High German lyric, such as Gennrich and Spanke.Footnote 9 But in using formal classification as a means to compare songs to one another, Gennrich, Spanke and others divorced the musical structure of individual songs from the social context in which those songs were composed.Footnote 10 Although Gennrich asks at the end of the Grundriss why poets chose particular forms, he provides no answer, passing over the question of what meaning musical structures might have carried for particular poets at specific historical moments.Footnote 11

Recently, musicologists and literary scholars have turned to the meanings that trouvère melodies might carry, but rarely in relation to melodic structure. Some have argued that textual meaning and musical structure are unrelated: John Stevens cites the importance of number in medieval music theory and sees number (the numerical match between number of syllables and lines and the number of pitches) as the only meaningful aspect of a song’s formal structure.Footnote 12 Daniel E. O’Sullivan, while renewing the call for literary scholars to consider melody as well as text, interprets the non-relation between textual and musical structures in a song by Chretien de Troyes as a rendering of the irony in Chretien’s text.Footnote 13 While Elizabeth Aubrey maintains that text and melody each follow their own logic and are to some extent independent and autonomous, she does suggest the structure of a song’s melody could mimetically represent its narrative arc;Footnote 14 she argues that medieval treatises show text and music to spring from the same razo, and therefore to be conceptually related.Footnote 15 Mary O’Neill notes the changes in the melodic structure of trouvère song throughout the thirteenth century, but attributes these to changes in musical taste, rather than new approaches to the expression of meaning.Footnote 16 Both Aubrey and O’Neill also move beyond Gennrich’s view of musical structure by considering tonal structure and small-scale motivic repetition.Footnote 17

Judith A. Peraino’s discussion of the Occitan descort provides an important methodological touchstone for this investigation of the jeu-parti.Footnote 18 The descort is a genre of troubadour song defined by its unusual structure: some descorts have different versification patterns (and presumably, therefore, a different melody) for each strophe, while others are isostrophic but multilingual. Peraino examines the meanings and associations of the word ‘descort’, arguing that ideas of social discord, lateness and a breaking of the alignment between sound and sense can be associated with the genre’s discordant musico-poetic structures. This discord is played out in performance, where singers must struggle to make sense of these ‘studies in performative disruption’.Footnote 19 I also want to make the case for viewing musical structure as a performance of meaning, though not in the same way as Peraino proposes for the descort. By considering the context in which poet-composers ‘performed’ particular musical structures (be that an act of composition or an act of live performance), I argue that it is possible to understand the ideas and values that were associated with melodic structure.Footnote 20

Such associations become particularly clear in cases where trouvères allude explicitly to their song-making as an act of ‘finding’ (trouver/inventio) or ‘dividing’ (partir/divisio).Footnote 21 Here, I examine each of these terms for their medieval resonances and show how the poet-composers for four jeux-partis performed these meanings through their use of musical structure. I close by considering how widespread these melodic structures were, and the extent to which invention and division lie behind such cases of musical structure.

FINDING AND LOSING SONG

Jehan de Grieviler begins his jeu-parti Sire Bretel, mout savés bien trouver (RS 899) by praising his opponent Jehan Bretel for his skill in finding songs:Footnote 22

Sir Bretel, you know truly, in my view, how to find (trouver) divisions and songsFootnote 23 and for this reason I would ask you, when does a noble lover make (faire) more loving songs: either when he has his lover at his disposal, or when he serves in hope, desiring that he will be able to have pleasure from his lover, each leading a good life? But tell me, I pray you, which of these states makes the heart more invigorated?Footnote 24

Two phrases in this opening verse make an explicit connection between song composition and rhetorical invention. First, there is the use of the term trouver. Since ‘trouver’ occurs only twice in jeux-partis to describe composition (as opposed to ‘finding’ in a more general sense), it is likely that listeners would have understood this to be a pointed reference to the rhetorical practice of inventio. Footnote 25 Second, the mention of the heart is a clear reference to a second aspect of rhetorical practice, memoria. The heart was considered to be the seat of memory in the Middle Ages, and here Grieviler explicitly connects the invigoration of the heart – and memory – to the invention of poetry and music.Footnote 26 Together, these phrases invite an interpretation of RS 899 in terms of rhetorical invention and its associated mnemotechnical practice, with which it appears Grieviler was familiar.

It is, in fact, very likely that Grieviler, an unordained cleric living in Arras, was educated in rhetorical invention, and that many of his listeners would have been too.Footnote 27 An affluent city and a political and religious hub, Arras boasted a population of which an unusually high proportion had received some form of clerical education. Carol Symes argues that the schools at the Abbey of St-Vaast and the cathedral educated many more men than were required to work at these institutions; Arras and its confraternity of jongleurs (known as the Carité des Ardents or the puy) probably therefore had an unusually high proportion of educated members.Footnote 28 As Jennifer Saltzstein has argued, ‘the genre [of the jeu-parti] was dominated by trouvères who were also clerics’.Footnote 29 A number of trouvères who participated in jeux-partis are addressed by the title ‘maistre’, a possible indication that the trouvère had benefitted from a clerical education.Footnote 30 That the clerical status of trouvères was particularly prized in Arras would suggest that listeners might have been attuned to signs of scholastic education in the structure and content of trouvères’ songs.

Scholastic and monastic education are likely to have included a study of rhetoric, whose key texts were Cicero’s De Inventione and the Rhetorica ad Herennium, possibly misattributed to Cicero.Footnote 31 The teaching of rhetoric in the Middle Ages has been widely discussed in scholarly accounts; I offer only a brief summary here.Footnote 32 In rhetorical treatises, inventio was a key pillar in the five-part scheme of rhetoric, consisting of invention, arrangement, style, memory and delivery. The Rhetorica ad Herennium places particular emphasis on invention as the most important of these.Footnote 33 An architectural model is central to Cicero’s theory of memory and invention: he suggests that one’s memory should consist of a series of rooms or niches in each of which an image is placed, which must be emotionally affective in order to stimulate the memory.Footnote 34 Medieval theorists followed Cicero’s teaching, sometimes using other spatial metaphors such as a beehive, book or grid instead of Cicero’s rooms or niches.Footnote 35 An author was to traverse the different locations of his or her memory (either walking through the different spaces or observing them from a stationary position) in order to find (literally) the things (each item in one’s memory is a res) that can be arranged to form their composition. Memory was thus a tool (machina) for invention.Footnote 36

The Ciceronian theory of invention permeated discussions of poetic composition, which could be found in the new genre of the ars poetica in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.Footnote 37 Perhaps the most famous example is Geoffrey of Vinsauf, who opens his Poetria nova with an extended comparison of poetic composition to architectural construction: an architectural blueprint, or the res of the poem, is first found, and then the building or poem is constructed from it.Footnote 38 Geoffrey places particular emphasis on the next stage of the compositional process, the technique of amplification, in which the poet would ‘clothe the matter [of the poetry] with words’.Footnote 39

Whether the poetic treatises of Matthew of Vendôme, Geoffrey of Vinsauf and John of Garland properly concern inventio, arrangement or style has been contested by scholars.Footnote 40 Unlike others – Douglas Kelly, for example – I am not concerned here with the extent to which specific aspects of rhetorical style such as prosopopoeia or circumlocutio can be applied directly to trouvère song.Footnote 41 For the purposes of my study, it is sufficient to note that in rhetorical or poetic composition, defined broadly, material was ‘found’ in the inventory of one’s memory and organised into a structured scheme from which it could be verbalised into a significant piece of oratory or poetry. This general model for inventio can be seen at work in romance literature and lyric compositions, despite the fact that in these genres, the precise procedures described in Ciceronian texts or in poetic treatises may not always be followed to the letter.Footnote 42

It is within this broad definition of inventio that I shall discuss trouvère song. Invention and memory have been discussed widely in relation to medieval music. Theodore Karp, Leo Treitler and others have hypothesised that chant was stored in the memory through ‘chunking’ and then reconstructed in performance,Footnote 43 an approach to memory and composition that may have also applied to polyphonic practice such as that outlined in the Vatican Organum Treatise.Footnote 44 According to Aubrey, the technique of invention was used by the troubadours primarily to find a melody appropriate to the register of the poetry that it accompanied; the shaping of a melody was left to the later stages of the rhetorical process (dispositio and elocutio).Footnote 45 Here, I take a different approach, while acknowledging that melodic formulae and registral propriety may both have been considerations for trouvères. Instead, I want to suggest that a trouvère melody might perform the process of invention in a way that was discernible to listeners.

With its overt references to musico-poetic composition, RS 899 (introduced above) draws attention to the way it was made and thus invites an analysis of its structure. In this jeu-parti, composed by Jehan de Grieviler and Jehan Bretel, the poetry of the first stanza shapes how the melody is structured:

Lines 1–4 introduce the debate by praising Bretel and posing a question. Then lines 5–8 present the two alternative choices of the dilemma, using the construction ‘u … u’ (either … or, indicated above in bold type). Finally, lines 9–10 conclude the stanza, as Grieviler turns once again to Bretel. Line 9 is separated from line 8 by the conjunction ‘mais’ (but), also indicated above in bold.Footnote 46

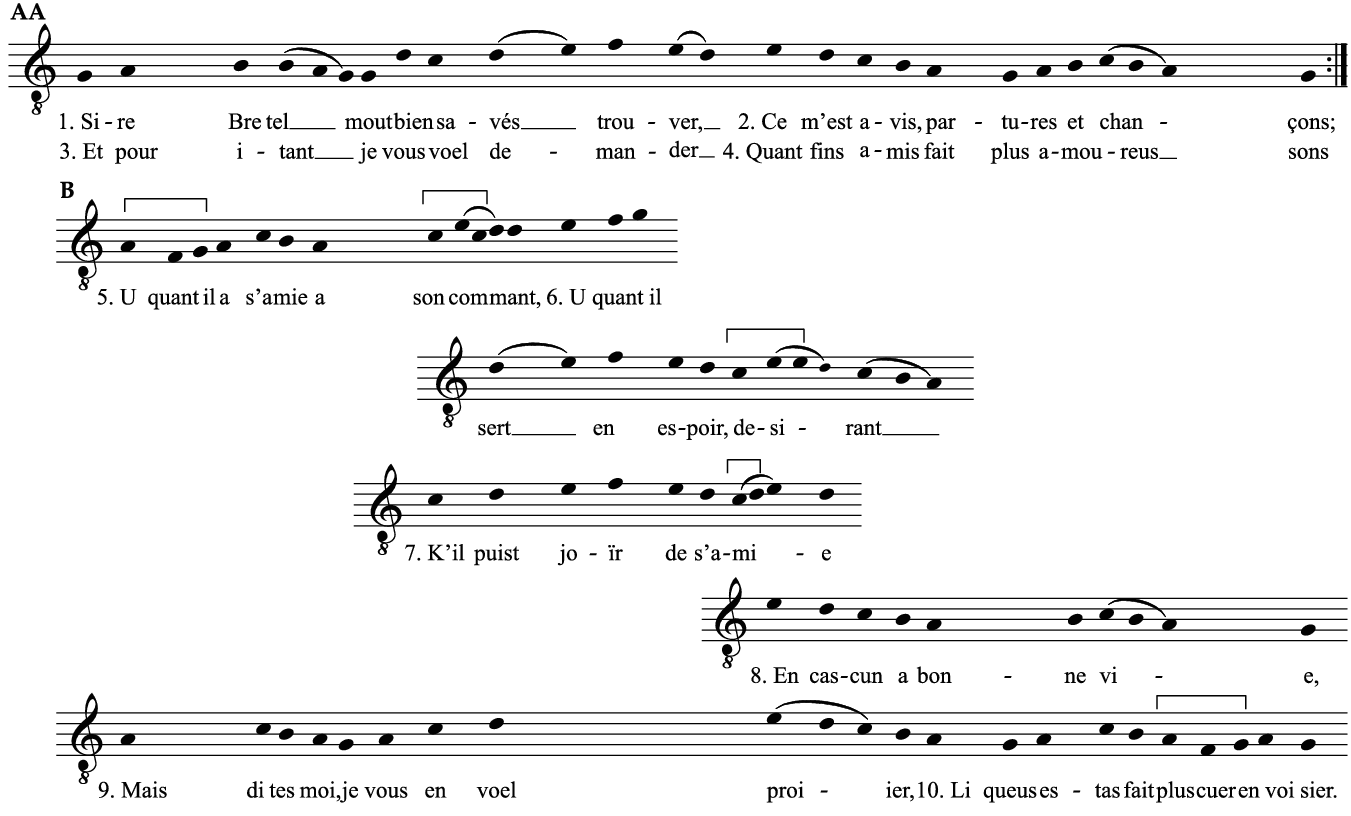

This tripartite poetic structure corresponds to melodic structure (see Example 1 for a transcription of the first stanza from chansonnier Z).Footnote 47 As Saltzstein shows for songs by Gace Brulé, the poetic structure of pedes-cum-cauda (AAB) was often complemented by a structural break in the melody at the end of the pedes and the start of the cauda.Footnote 48 Sire Bretel is in pedes-cum-cauda form (AAB) and melodically articulates its textual structure in a similar way. Lines 1–4 consist of a pes (lines 1–2) that is repeated (lines 3–4), in which the melody outlines a cadence on G, moves to a secondary tonal centre on d, and then returns to G.Footnote 49 Lines 5–8, the first part of the cauda, repeat this melodic material in a more elaborated fashion, but starting from a, rather than G (the song’s primary pitch). Line 5 begins with an elaboration of a and avoids G as it moves to d. Starting in the tonal region centred on d, line 6 moves towards G but never arrives, finishing on the open pitch a. Line 7 is centred strongly around d, after which line 8 makes the return to G, causing tonal closure to coincide with the end of a structural unit of poetry. Lines 9–10 then repeat the tonal process a–d–G yet again, but in a different way from the opening pes. The two latter sections of the melody thus closely follow the pedes but also prolong tonal expectation by avoiding G until the end of each section. The relationships between the three sections of the melody can be seen clearly in Example 1, which aligns melodic sections by pitch.Footnote 50

Example 1 Sire Bretel, mout savés bien trouver (RS 899), stanza 1 from chansonnier Z, aligned by pitch

A few aspects of the general approach to melody manifest in Example 1 warrant discussion. First, the example treats multiple pitches within a neume as equivalent to pitches set syllabically, such as ‘avis par-’ in line 2 and ‘-rant’ in line 6. This conception of melody requires a more flexible approach to text–music relationships than has previously been accepted; as Elizabeth Eva Leach has recently argued in relation to melodic variants in trouvère song, however, ‘the flexibility of text-music alignment can be seen to support the idea that basic pitch string is a more fundamental aspect of melody than its syllabification’.Footnote 51 Second, the end of a poetic line is not always the end of a melodic section. Line 6 opens with three pitches that correspond to the end of line 1; the rest of the pitches in that poetic line span the end of line 1 and the start of line 2.Footnote 52 Previous analyses of trouvère song almost always divide the melody only according to poetic lines because syllable count and rhyme was an important aspect of poetic structure.Footnote 53 While the relationship between melodic structure and poetic line was clearly a site of play for trouvères – the close correspondence between the start of line 8 and lines 2 and 4 in this song, for example – poetic line was not the only measure of melodic structure.

As Example 1 shows, the three sections of the melody (lines 1–4, 5–8 and 9–10) are closely related, and the resulting melodic structure would probably have been audible to listeners.Footnote 54 It is through this melodic structure that Grieviler presents a process of Ciceronian invention to listeners. The process starts by finding things laid down in one’s memory. In this jeu-parti, Grieviler first sets out a melody (the pedes) that can be memorised. Because music is ephemeral, a melody goes out of existence as soon as it has been performed, save for its existence in the memory of singers and listeners.Footnote 55 The performance of the pedes thus automatically entails the commitment of the opening melody to memory, the machine of invention. In the cauda, Grieviler then goes about the process of ‘finding’ the melody. He works through the melodic material that was established in the pedes, this time in a more elaborate form, amplifying it with melodic embellishments (indicated in Example 1 by brackets).Footnote 56 What is more, the melody of lines 1–2 is not simply repeated in an embellished form: a portion of the melody is stated and another section begins, not where the first portion leaves off, but at an earlier point. Since portions of melody in lines 5–8 overlap, it seems as if the melody is being created from a melodic blueprint (lines 1–2) that has been previously fixed. Grieviler revisits parts of the pedes melody in whichever order he wants since it is stored in his memory.

It is important to distinguish here between what Grieviler and Bretel really did to compose this song, and how listeners understood a song in performance – both of which can only be hypothesised. It is likely that Grieviler did not set down the pedes and then compose the cauda in the linear way that I imagined above: he probably had some conception of the cauda when he created the pedes. But for listeners, the song is a linear process which the lyric figure of Grieviler initiates. It was probably understood as a musical version of rhetorical invention for three reasons. First, the technique of invention was widely taught in monastic and cathedral schools, at which many of Grieviler’s audience would have been educated: as Carruthers has argued, ‘it is likely that many ancient and medieval people, trained in oratory and/or in chant and prayer, “heard” and “saw” a piece performed in their minds’.Footnote 57 Second, a rhetorical approach is explicitly signalled by the word trouver and the metaphor of the heart for the memory in the opening stanza, which are uncommon enough to have been noted by listeners. Finally, invention was an intellectual process, and therefore carried prestige among an educated audience; because of this prestige, I suggest that listeners would have been inclined to listen out for compositions that made use of invention, especially when they (in the form of named judges) were asked to judge most jeux-partis at their conclusion.Footnote 58

De çou, Robert de le Piere (RS 1331) is another jeu-parti with a similar melodic structure that draws attention to the act of song-making (see Example 2). Here, the musical rendering of Ciceronian invention has implications for how the song is to be interpreted.Footnote 59 Like RS 899, RS 1331 is in pedes-cum-cauda form, with an opening melody (lines 1–2) that is repeated (lines 3–4) before a more elaborate section of melody (lines 5–9). First, lines 1 and 2 establish the melodic material on which the cauda is to be based. Line 5 acts as a small tail to the pedes, repeating much of line 4 but ending on C rather than F.Footnote 60 This accommodates the poetry well, since Lambert Ferri, the trouvère of this first stanza, starts his question to Robert de le Piere at line 6, marked by an octave leap up to c. Lines 6 to 9 then each work through a bit more of the melody, only cadencing onto D, the primary pitch of the cauda, at the very end of the song. As in RS 899, more and more of the opening melody is explored in lines 6–9, with overlapping chunks of melody. The break between line 1 and line 2 is not replicated in the way that the melody is explored in lines 7 and 8: G is connected to F in both of these lines, obscuring the structural break in the melody of lines 1 and 2.

Example 2 De çou, Robert de le Piere (RS 1331), stanza 1 from chansonnier A, aligned by pitch

In this song the principle of inventio is not signalled explicitly by the word trouver, but rather by its opposite: Ferri states that Robert has ‘lost his style and that of his song’. As if to prove that he himself is able to find melodies successfully, Ferri appears to follow a process of invention, setting out a melody for Robert in the pedes, and then using this to build a more elaborate melody in the cauda. With a synoptic view of the melody stored in his memory, Ferri is able to begin poetic lines 6–9 wherever he chooses to create the pattern of overlapping melodic segments that Example 2 shows.

As Ferri is heard to construct the cauda, he also appears to embellish the melody by adding various stepwise figures (indicated by brackets in Example 2), a melodic version of the rhetorical technique of amplification. The placement of these embellishments in relation to the opening four lines of the song also suggests that this is a melodic rendering of mnemonic technique. The additional embellishment in line 8 corresponds to the break between lines 1 and 2, while the additional embellishments in lines 6 and 5 correspond to the fourth syllables of lines 1 and 2 respectively. As lines 1 and 2 have eight and seven and syllables respectively, the fourth syllable in each line forms the midpoint. Listeners might even expect a lyric caesura at the fourth syllable (although caesuras are only properly found in decasyllabic verse), lending extra structural significance to these points of the poetry. While the embellishments of lines 5, 6 and 8 do not occur at the fourth syllable of their own lines, they correspond to the structurally significant points of the melodic outline given in lines 1 and 2. The melody thus presents Ferri traversing the rooms of his memory in which the melody is stored, amplifying structural breaks in the poetry with embellishments that might help him to orientate himself and find the section of the melody.Footnote 61 Again, this is not to say that Ferri composed the melody in this way, but rather, that listeners might have heard the melody as a performance of the invention process.

The construction of the melody of RS 1331 is particularly important for the themes of song-making that emerge in the debate between the two trouvères. Ferri opens the debate with an accusation that Robert de la Piere has lost his style:

In the remainder of the debate, Robert argues that he has no need to keep singing because he has recently married. Ferri stubbornly maintains that Robert’s lack of style must spring from a defect in his character, since those who are happy in love should be able to sing about it. To emphasise this point, Lambert compares Robert to a nightingale in stanza 5 of the song:

With this simile, Ferri makes reference to the ambiguous status of birdsong, which, as Elizabeth Eva Leach has shown, held a liminal status in medieval theories of voice. Priscian, for example, argues that there are four categories of vox, depending on four combinations of two binaries: whether the voiced sound can be written (that is, literata), and whether it is uttered by a rational being (that is, articulata).Footnote 62 By comparing Robert to a nightingale, Ferri suggests that he used to compose songs that could be written down and that were rational, since the nightingale deliberately woos his lady-bird. Now (at the time of performance), Robert only utters noises that are irrational and unwritable.Footnote 63

The debate in RS 1331 thus explores what makes a melody rational. Humorously, Ferri creates a melody that, on its surface at least, seems to be irrational. First, the range of the opening pedes (an eleventh) is extreme and unusual: this is the largest range in the opening four lines of any surviving jeu-parti.Footnote 64 Secondly, the song has a tonal structure that the music scribes for the different versions of the song appear to have found problematic. In all versions of the song, line 2 ends on F and line 9, the final line of the song, ends on D (see Example 3). These pitches have structural significance because they mark the end of two principal sections of a melody in pedes-cum-cauda form. Variation occurs between the sources at the end of line 4, where chansonnier A gives F and chansonniers a and Z give D.Footnote 65

Example 3 Comparison of versions of De çou, Robert de le Piere (RS 1331), lines 2, 4 and 9

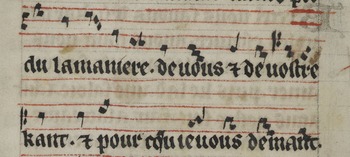

The discrepancy in final pitches of line 4 in the different sources might indicate that the music scribes had difficulty in deciding whether the primary pitch of the opening four lines should be D or F. The scribe of chansonnier A made line 4 match line 2 so that the two pedes both end on F; the scribes of chansonniers a and Z opted to make D the final pitch of both pedes and cauda, thereby compromising the double pedes structure. Either solution leads to tonal disunity of some kind. This seems to have caused particular problems for the scribe of A, whose confusion is visible in the erasure and clef change above ‘vostre’ (l. 4) (Figure 1). This difficulty in writing down the melody recalls the distinction made by Priscian and others of writable versus unwritable music (il/literata).

Figure 1 Chansonnier A (Arras, Bibliothèque municipale, MS 657), fol. 143v. Photo: Bibliothèque municipale d’Arras. Reproduced with permission

The melody of RS 1331, on the one hand, is a highly rational exercise of invention, demonstrated through the melodic structure of the cauda. On the other hand, it pushes the boundaries of what is singable (its range) and what is writable (the scribal variants). The nightingale allegory holds the key to this dichotomy: in conception the song is rational but in sounding performance it borders on the irrationality of vox illiterata. In the jeu-parti, Ferri is responsible for the rational construction of the melody since he sings first in the debate. Robert is left to sing the melody back to Ferri, re-voicing sounds which imply that he, Robert, is an irrational creature. He is presented as lacking the rational capacity for the intellectual endeavour demanded by a process like invention. By comparison with Robert and in his performance of invention through melodic structure, Ferri presents himself as a rational inventor.

In finding their melodies through a process of invention, trouvères were thus able to create musical structures that were meaningful. In RS 899 and RS 1331, melodic structure results from a real-time performance of the process of invention. If, as I have argued, the structure of a song was understood to manifest the principles of rhetorical invention, the cultural significance of invention would then have become aligned with the meaning of that melody. In both examples here, invention is performed through melodic structure to demonstrate the intellectual prestige of a trouvère, asserting his educated status in relation (or opposition) to his opponent in a jeu-parti.

DIVISION, SUNG AND SOCIAL

Trouvères were frequently explicit about the acts of division (partir in French and divisio in Latin) that were central to their conception of the jeu-parti. The name of the genre itself literally means ‘divided game’, and the genre label ‘jeu-parti’ is used by trouvères in their songs to refer to their musical debates, as well as by scribes in a handful of the major chansonniers that transmit jeux-partis.Footnote 66 As shown in Appendix 1, twenty-nine jeux-partis open with a reference to dividing, after which the first trouvère will normally present the two opposing (that is, divided) sides of the dilemma.Footnote 67 The term ‘partir’ therefore has a performative function, in the strict sense established by Austin: the speech act is itself the act, in this case creating the situation in which a choice needs to be made between two alternatives that have been divided.Footnote 68 My contention is that in dividing their songs in ways that can be seen in melodic structures, trouvères could enact and perform other types of division (cognitive and socio-political) through song.

Division played an important role in theories of rhetoric as the counterpart to invention. Authorities such as Quintilian recommend that division should be used to enable the memorising process.Footnote 69 By dividing a text into manageable chunks, the text could be stored in one’s memory and recalled through a process of re-composition, bringing together the parts in the right order thanks to the hierarchical structure of one’s memory.Footnote 70 Division was therefore the means by which a reader exercised rational control over a text. The use of division in the service of rationality is also seen in texts that categorise fields of knowledge. Johannes de Grocheio, for example, cites Aristotle’s De partibus as a model for his various divisions of music in the Ars musice: ‘[Aristotle] made these things [about animals] more perfectly and precisely known through knowledge of parts, in the book which is called De partibus.’Footnote 71 With a similar rationalising impetus, the addition of small strokes in music notation known as divisio modi is described by music theorists such as Franco of Cologne and Johannes de Garlandia as a way of showing the division between semibreve groups.Footnote 72 As Mikhail Lopatin and Anna Zayaruznaya have shown, theoretical and poetic notions of divisio influenced composers of polyphony in the fourteenth century.Footnote 73

Division is often the term used when an either/or question is formulated. Cicero, for example, states that ‘division separates the alternatives of a question and resolves each by means of a reason subjoined’.Footnote 74 Division is associated relatively early, therefore, with the either/or opposition that is found in the jeu-parti and was used in the service of reason, but Paul Remy has shown that by the thirteenth century, division had come to signify something slightly different. In three twelfth- and thirteenth-century French contexts, the term jeu-parti is used to mean a difficult or unfavourable choice: (1) in the romance, an impossible decision for a character; (2) in descriptions of chess problems; (3) as the name for a genre of song.Footnote 75 In these uses of the term ‘jeu-parti’, the idea of a dilemma is preserved, but emphasis is placed instead on how the state of dilemma causes people to act or to be paralysed by inaction. Once an agent has chosen which side of the dilemma to follow, the course of action will be opposed to the alternative. Division causes opposition, whether this be within one’s mind (chess, romance) or between two figures (the sung jeu-parti).

The stark opposition that was evoked by the term partir in twelfth- and thirteenth-century contexts shaped the poetry of jeux-partis, which were written in what Michèle Gally has termed a ‘mode dilemmatique’.Footnote 76 Gally and Georges Lavis have shown that poets created stanzas not through developing a single line of reasoning but rather by placing discrete (and often opposing) textual units one after the other. Conjunctions such as ‘mais’ (but) or ‘ains’ (on the contrary) were trigger words that divided one textual unit from another, as I demonstrated for RS 899 above.Footnote 77 Textual units themselves were frequently self-contained in the form of proverbs, maxims and comparisons.Footnote 78 Instead of using poetry to persuade listeners of the validity of their arguments, trouvères would juxtapose chunks of text for effect, creating an ‘argumentative display’ that dramatized the division between two poets.Footnote 79 The division of a stanza into discrete and polemic textual units thus enabled poets to render division performatively.

I showed above that melodic structure could be interpreted in relation to the structure of the text: in Sire Bretel, mout savés bien trouver (RS 899), for example, the three renditions of the same melody (in various states of elaboration) correspond to three sections of the first stanza.Footnote 80 But there are also ways in which trouvères would invoke a state of textual dilemma or division that was mirrored by the melody; put another way, both melody and text can be seen to spring from the same cognitive process of division. The textual invocation of the state of dilemma can take several forms: sometimes a trouvère will use the verb partir performatively, saying, for example: ‘I’ll divide this for you.’ In Example 4, which gives the first two lines of the jeu-parti Lambert Ferri, je vous part, the verb ‘part’ is used to divide the melody into two tonal areas, one centred on F and the other on D.

Example 4 Lambert Ferri, je vous part (RS 375), lines 1–2

In many more cases, a question is simply asked (demander) or a response requested (responder), but dilemma is created through textual formulae: a comparative question, beginning with ‘li quieus’ (which); the constructions ‘u … u’ (either … or) or ‘li uns … li autre’ (the one … the other); and the conjunction ‘mais’ (but). With varying degrees of performativity, these textual constructions act as ‘metapoetic’ commentary, a term which I borrow from Lopatin’s examination of divisio in trecento music.Footnote 81 They are verbal utterances that have meaning within a song’s semantic realm, but also describe a song’s construction. As the following examples show, trouvères’ use of the term partir manifests itself in divisions of tonal space or melodic motif.

In the second stanza of Biau Phelipot Verdiere, je vous proi (RS 1674), the trouvère Phelipot Verdiere uses the verb partir in an overtly metapoetic way: ‘Lambert Ferri, since you have divided this so sweetly for me, you know well that I’ll take the better alternative, for it cannot be otherwise.’Footnote 82 In describing his act of division (parti) as ‘sweet’ (deboinairement) Phelipot could simply be referring to the choice of sides that he must take in the debate: he sees one alternative as more defensible than the other, and chooses it. Viewed through a metapoetic lens, Phelipot’s use of the adverb ‘deboinairement’ to describe the way in which Lambert has set out the dilemma in the first stanza might suggest that the musical and poetic setting of that stanza is in some way also ‘deboinaire’. The following analysis explores the division of melody before returning to the aesthetic question of what ‘deboinaire’ might mean in this instance.

As often with jeux-partis, RS 1674 is transmitted with two melodies: one in chansonnier A, the other in chansonniers Z and a.Footnote 83 The following discussion treats the melody from A, which is more motivically unified than the melody in Z and a, and exemplifies division clearly through its use of motif. The melody of RS 1674 in A is intricately woven, such that aligning the melody by pitch becomes a very difficult task. As Example 5 shows, the opening pes can be divided into three different motifs, although whether any of these pitch strings has an identity strongly marked enough to constitute motivicity is questionable.Footnote 84 Each of the motifs is reused and elaborated in the cauda to create a melody that is structurally more complex than the jeux-partis discussed above. Example 5 gives one possible motivic structure for the cauda.Footnote 85 By contrast, the tonal structure of the song is relatively clear, although it may not have been obvious to listeners on first hearing the song. The opening pes emphasises F as the tonal centre through an opening cadence (motif p) that also closes line 2. Line 1 also ends on F, though with a turn figure G–F–E–F that contributes to the primacy of F in the tonal hierarchy. The only deviation in the opening pes from the tonal centre F is at the start of line 2, where D/C are fleetingly offered as a possible secondary tonal goal: the tonal trajectory of each pes is therefore F–D/C–F.

Example 5 Motivic structure of Biau Phelipot Verdiere, je vous proi (RS 1674) in chansonnier A

At the end of the opening pedes, F seems to have been established as the tonal centre (although this would only be clear if the pitch b was realised in performance as bfa (likely) rather than bmi (unlikely)). As the cauda of RS 1674 unfolds, the primacy of F over D/C seems, for a while, to continue, and the close motivic correspondences between pedes and cauda might prompt listeners to expect the tonal trajectory of the cauda to mirror that of the pedes. Perhaps it would have been surprising, therefore, that the cauda finishes on C rather than F, suggesting that C functions as the primary pitch of the cauda. By the end of the cauda, C has been repeatedly emphasised as the tonal centre of this part of the melody. A difference in tonal centres between pedes and cauda is not unusual within the jeu-parti repertory, and was perhaps a resource used specifically for this partitioned game: in the presence of metapoetic markers, one can imagine such tonal division having divisive significance. However, in this melody, the shift of tonal centre is marked more subtly than the placement of a metapoetic marker at the boundary between two tonally distinct sections.

At what point in the melody would a listener recognise that F has given way to C as the tonal centre? The pitch b in line 5 would probably have been sung as bfa because it is followed by a stepwise descent to F; for line 5 at least, F remains the tonal centre. The B in line 6, by contrast, ought to be realised Bmi; once Bmi has been reached in line 6, b (fa or otherwise) is not heard for the remainder of the song, suggesting a definite shift away from F and towards C. While the status of B/b would have been important in defining the tonal space of the melody, the text also provides a point of orientation for listeners. Ferri places the word ‘mais’, a conjunction that signals textual division, at a crucial juncture in the melody. In this case, ‘mais’ introduces the sting in the tail of the amorous scenario: ‘his Lady asks him and beseeches him to go to speak with her privately in a secret place, but (mais) he knows for certain that if he goes there he will be seen by slanderers’.Footnote 86 From the start of line 5 to ‘mais’ in line 7, the melody has increasingly shifted from F to D, matched by the increasing frequency of derivatives of motif r.Footnote 87 In the pedes, D/C was followed by F and motif r by motif p, giving the overall tonal trajectory F–D/C–F. At ‘mais’ in line 7, p is indeed stated, but the word ‘mais’ indicates that this motif should not be considered to be connected to what comes before: it is the start of a new unit, a return to the motivic material of the song’s opening, divided from what comes before textually, and thus also melodically. The use of the word ‘mais’ at this moment tells the listener that the tonal profile F–D/C–F of the pedes is not going to be the tonal profile for the cauda too. After the word ‘mais’, all statements of p are extended so that they descend to D/C: it becomes clear that F will yield to D/C, as it emphatically does in the final two lines of the song.

This reading of the motivic division of the first stanza is supported by Phelipot’s response in the second stanza. He places the word ‘mais’ at exactly the same point in the second stanza as Ferri does in the first stanza, suggesting that for both trouvères this marked an important point of poetic, but also melodic, division. But what was it about the potential of this melody to be divided that might have made it ‘sweet’ (deboinaire)? The adjective deboinaire also has the sense of ‘dignified’, suggesting that Phelipot might have found the orderly coinciding of textual and tonal division to be a noteworthy aspect of Ferri’s melody. The description of musico-textual relations as ‘deboinaire’ would also suggest that Phelipot finds the alignment of textual and musical division to be aesthetically pleasing. This pleasure is not excessive or lascivious, but dignified, gentle and sweet (all possible meanings of deboinairement).Footnote 88 The pleasure that Phelipot takes from the division of RS 1674 is thanks to the dignified way in which oppositions within the text are complemented by tonal opposition. That Phelipot can take a righteous pleasure in the use of textual and melodic division suggests that division has been deployed in a morally sanctioned way in RS 1674. Given the utility of divisio technique in categorising and disciplining knowledge, the pleasure found in this kind of divisio could only be rational (as opposed to corporeal) and was therefore morally permissible. As a device that organises and categorises knowledge, divisio also had an intellectual cachet, similar to the prestige associated with inventio that I explored above. Phelipot thus praises Ferri for his creation of a musico-poetic complex in which division has the potential to do intellectual work.

The conjunction ‘mais’ was not the only word that could be deployed to create division. As explained above, the construction ‘u … u’ (either … or) was used to set out the two equally unpalatable sides of the dilemma from which the second trouvère in a jeu-parti had to choose. In Or coisisiés Jehan de Grieviler (RS 861), Jehan de Marli invites Jehan de Grieviler to make a difficult choice: to have your lady naked in your arms every night but in your dreams, or to have the solace and company of your Lady in reality but for only one day in your whole life.Footnote 89 Although ‘u’ is used only once in this opening stanza, the conjunction nevertheless divides the dilemma for Grieviler.

Parallel to his act of textual division, Marli creates a melody that is tonally divided. As Example 6 shows, the opening line of the song marks either F or G as its tonal centre. The break after ‘coisisiés’ (marked by the fermata in Example 6) would argue for F as the tonal centre, while the statement of motive p′ at the end of line 1 turns an inconsequential pitch string (marked p in Example 6) into a cadential motif that implies G as the primary pitch. That G may be the tonal centre is also supported by a stylistic feature of jeu-parti melodies, in which the primary pitch is usually one step above the lowest pitch of the melody.Footnote 90 By the end of line 2, the melody has shifted to a different tonal and registral realm, centred on C. The same cadential formula a fifth apart is used for the ends of line 1 and line 2; having listened to the opening pedes, it is therefore likely that the listener would hear G as one tonal centre and C as another.

Example 6 Or coisisiés Jehan de Grieviler (RS 861), lines 1–2

The division of tonal space according to two tonal centres shapes the remainder of the song. Example 7 gives the text and melody of the first stanza of RS 861 aligned by pitch. As for the cases discussed above, the cauda explores the melody of the pedes in a non-linear fashion, perhaps indicative of a process of invention. Notably, the start of each poetic line in the cauda coincides with a jump backwards in the melody, except for the start of line 6, which therefore sticks out as unusual. While the beginnings of lines 5, 7 and 8 are marked structurally by their move to an earlier part of the melody, line 6 is marked as structurally significant in a different way. Opening with the conjunction ‘u’, the beginning of line 6 corresponds to the point in the pedes where the melody begins to move from a higher tonal area centred on G to a lower tonal area on C (marked in Example 7 by an unbroken vertical line). Although G need not be an absolute boundary between the two tonal regions, the use of ‘u’ (or) at this point encourages the melody to be heard in this way. The word ‘u’ is used to divide the two alternatives of the dilemma, but also divides the tonal space in two, causing the melody to be heard as a kind of tonal either/or, consisting of opposing parts. To highlight this further, G is sung to an ‘ou’ vowel at the same point in the melody in previous lines (marked in Example 7 by a dotted box), a sonic play on the metapoetic potential of the conjunction ‘u’ to divide textual and tonal space.

Example 7 Or coisisiés Jehan de Grieviler (RS 861), stanza 1 in chansonnier a, aligned by pitch

Having heard this division of tonal space, Grieviler has a choice whether to use the divided structure that Marli has created, or to interpret the melody in a different way. By the end of the first stanza, it has become clear that the melody is tonally divided, with two tonal centres of G and C. The opening confusion between the places of F and G in relation to one another and in the tonal hierarchy has been solved. Grieviler chooses to subvert the tonal hierarchy established by Marli, by careful use of the word ‘partés’ (see Example 8). In his opening address, Grieviler thanks Marli for ‘hold[ing] me in such high esteem that you divide [this] for me’.Footnote 91 While the opening line of the second stanza has no clear cadence on F, the third line of the stanza has a strong syntactic break following the word ‘partés’, much stronger than after ‘coisisiés’ in the first stanza. At this moment, the pitch string F–G–G–F is made to function as an emphatic cadence on F, highlighted by the metapoetic term ‘partés’. What is more, whereas line 1 of the first stanza ended with a syntactic break that emphasised G as a tonal centre, in the second stanza, both lines 1 and 3 of the melody (poetic lines 9 and 11) end with an enjambment that negates a sense of G as a tonal centre. Grieviler thus chooses to reverse the tonal hierarchy that Marli sets up in the first stanza, in which F was subordinate to G.

Example 8 Or coisisiés Jehan de Grieviler (RS 861), lines 9–12

Example 9 Sire Michiel, respondés (RS 949), stanza 1 in chansonnier T, aligned by pitch

The manipulation of metapoetic terms in this song shows the possible range of meanings that formal structure could carry. Both trouvères use division and its gamut of textual devices to shape the tonal space of the song, but in different ways: Grieviler not only divides the tonal space in a different way from Marli, but he also divides himself from Marli. Music and text could be manipulated to render the opposition between two trouvères in the structure of a song, which in turn encouraged them to take an oppositional stance to one another.

Opposition between trouvères is clear in the language that they use to describe their debates. While sometimes paying homage to one another, as has been shown for Biau Phelipot Verdiere (RS 1674) and Or coisisiés Jehan de Grieviler (RS 861), jeux-partis are full of insults that bristle with hostility. Trouvères would also on occasion refer to their jeu-parti with words that variously mean quarrel, struggle, discord and even battle or war.Footnote 92 Emphasising the agonistic aesthetic of the genre, trouvères thus associated the jeu-parti with a different nuance of the meaning of divisio. The term could be used to indicate the process of intellectual division through classification but could also mean ‘estrangement, dissension [or] disunion’.Footnote 93 Similarly, pars (the etymological root of the French partir) could mean something fairly neutral like ‘constituent part’ or could convey the more loaded sense of a ‘party’ with which one might side in a debate or conflict.Footnote 94 The French ‘faire parties’ was even used to describe two opposing sides in a tournament.Footnote 95 While it is not clear that partir has this antagonistic sense in all jeux-partis, the striking frequency with which trouvères return to this word in jeux-partis suggests that an aesthetic of violent opposition permeated performances of the genre.

APPLYING INVENTION AND DIVISION TO THE TROUVÈRE SONG CORPUS

In the case studies discussed so far, invention can be seen in melodic structure for songs that make explicit reference to acts of invention (‘trouver’ in RS 899 and ‘perdu’ in RS 1331) and in songs without such explicit reference (RS 861 and RS 1674). Invention can therefore be the cause of melodic structure whether a metapoetic term relating to invention is present or not. By contrast, I consider division only to be present in the structure of a melody when it corresponds to a division in the structure of the text, caused by words such as ‘u … u’ (either … or) or ‘mais’ (but).

This observation is borne out by the words that trouvères use in songs to describe their compositional acts. By comparison with the troubadours, who reflected extensively on their musico-poetic practice in their songs, the trouvères do not demonstrate the same reflexivity.Footnote 96 Table 1 presents the frequency of different compositional terms in the first stanza of the songs in Tischler’s complete edition of trouvère song.Footnote 97 Trouvères use the verb ‘to sing’ (chanter) most frequently by far, typically in the phrase ‘I must sing’ (chanter m’estuet) or ‘I will sing’ (chanterai), often following a description of springtime and birdsong. These descriptions present song as a spontaneous vocalisation of desire for the lady; as a spontaneous act of creation, the verb chanter therefore does not shed light on the processes of creating and shaping a song. Trouvères speak of ‘making a song’ (faire) in 122 songs, of ‘beginning a song’ in thirty-three songs, and of ‘renewing’ their song (renouveler) in nine songs. In only twenty-six songs does the poet speak of ‘finding’ (trouver) a song.

Table 1 References to composition in the first stanza of trouvère songs

Each of these terms tells us a bit more about how trouvères might have represented their processes of composition. The most common of these, faire, gives little specific information about the compositional process, but does perhaps suggest that trouvères thought of their songs as objects to be ‘made’; ‘to make a song’ seems to have had roughly the same meaning as ‘to sing’, chanter, since in forty-three songs both verbs are used in the opening stanza. The verb trouver is used far less frequently by trouvères and almost never in jeux-partis.Footnote 98

The verb ‘to divide’ (partir) is, by contrast, found extensively in jeux-partis. As the list in Appendix 1 shows, sixty-seven (35%) of the approximately 190 surviving jeux-partis use the word partir or its derivatives.Footnote 99 That such a significant proportion of jeux-partis is named by their trouvères as an act of division suggests that this was a fundamental aesthetic premise of the jeu-parti, but not of other trouvère songs, which are never described as being created through ‘division’. Textual markers of division (‘partir’, ‘u … u’, ‘li qieus’, ‘li uns … li autre’, ‘mais’/‘ains’) appear very frequently in jeux-partis but rarely in other genres of trouvère song. Melodic division, which relies on division in the text, is therefore an aesthetic limited to the genre of the jeu-parti. Invention, on the other hand, is a melodic principle that is independent of the semantic content of song texts, and might therefore be found not only in the jeu-parti but in other genres as well.

To ascertain how widely the structuring principles of invention and division are found, the entire repertory of jeu-parti melodies was tested. This sample was chosen because it enabled invention and division to be tested simultaneously. Appendix 2 gives the RS numbers for all melodies for jeux-partis that are extant. Because some jeu-parti texts are transmitted in different manuscripts with different melodies, the sources for each melody are given alongside each RS number. (RS 258, for example, has a different melody in each of a, A and Z, and these different melodies are placed separately in the table.) The melodies are sorted into three groups according to the extent to which they demonstrate the structural principle of invention. In group 1, the melodies strongly exhibit invention; all or most of the melodic material of the cauda is derived from the pedes (or equivalent, if the song is through-composed). Group 2 melodies are those that could be heard to have some invention, that is, their cauda may partly be based on melodic material introduced in the first section of the melody. Group 3 melodies have little or no discernible melodic structure that corresponds to the process of invention. Within each of these groups, the presence of division in the first stanza of a song is indicated.

Of a grand total of 168 different melodies, forty-one exhibit strong invention, sixty-three could be interpreted to have some invention and sixty-four have little or no invention to speak of. Group 1, whose melodies make use of thorough-going invention technique, constitute 24.4 per cent of the extant melodic record, a minority, but nevertheless a not insignificant proportion. Group 1 and group 2 together – that is, melodies that I believe to demonstrate some use of the technique of invention – make up 61.9 per cent of the total number of melodies. Invention is therefore found to some extent in the majority (albeit it is fairly slight) of jeu-parti melodies. The categorisation of melodies here is, unavoidably, subjective; some group 2 melodies could belong in group 1 when analysed by a generous analyst, while a sceptical analyst might see some group 2 melodies as belonging in group 3. Appendix 2 should therefore be taken as a rough indication of the practice of melodic invention, rather than a precise account.

Of the 168 melodies, sixty-five are set to first stanzas in which textual division corresponds to structural division in the melody. This amounts to 38.7 per cent of the total, a minority, but again, not an insignificant one. The proportion of melodies with division changes slightly when the presence of textual division is taken into account. Songs whose first stanza does not contain the textual divisions of ‘li qieus’, ‘u … u’, ‘mais/ains’, or ‘li uns … li autres’, or the metapoetic term ‘partir’, are signalled in Appendix 2 in square brackets. These twenty-seven settings of the first stanza all fall in the lower half of each group, that is, they contain no melodic division because their texts are not divided. There are thus 141 melodies (corresponding to ninety-five different texts) for which at least one of the five most common textual markers for division is found in the first stanza. It is only in this latter group that composers could choose to create melodic division, according to my definition of the term. In 46.1 per cent of these cases, composers chose to match division in the text with division in the melody.

A number of trends in Appendix 2 stand out. First, invention and division are correlated to one another: the stronger the presence of invention, the more likely there is to be division too. In group 1, thirty-two of the forty-one melodies (78.5%) have division. The correlation is stronger still when the texts that lack textual division (in square brackets in Appendix 2) are omitted from the count. Thirty-two of the new total of thirty-six melodies (88.9%) in which melodic division is possible have division. (RS 691 in T may also have had division, but the absence of some of the cauda makes this moot.) Group 3 shows the reverse: 14.1 per cent of melodies (18.0% if the bracketed melodies are omitted) in this group have melodic division. This finding is not surprising. Highly structured melodies, such as those found in group 1, are more likely to have structural breaks that could be made to coincide with divisions in a text. Of the nine melodies in group 3 that exhibit divided melodies, four have a division in the text between the pedes and cauda, or between pedes (RS 704, RS 840, RS 1293, RS 1672). Three have motivic repetition that is significant but that is not enough to be considered invention (RS 927, RS 952, RS 1584) and two have a shift in register (RS 618, RS 1817).

Second, there is some correlation between the presence of invention and whether the pedes and cauda of a song have significantly different ranges. Table 2 gives the melodies for which the lower or upper limit of the cauda differs by more than a major third. Only two of these melodies are from group 1: RS 403 and RS 258 (in A). In RS 258 (A), the elaboration of melodic material from line 1 is extended higher and higher for each iteration during the cauda, a gradual expansion of the song’s ambitus. In RS 403, the cauda moves up to a new higher tessitura for lines 6 and 7 before returning to the tessitura of the pedes and continuing the process of invention.Footnote 100 In all of the group 2 examples in Table 2, the extension either downwards or upwards is caused by the introduction of new melodic material not found in the pedes; in these group 2 melodies, this new material is the principle cause for the melody being in that group, rather than group 1.

Table 2 Jeux-partis with significantly different ranges in pedes and cauda

* RS 1666 (V) is through-composed.

Certain sources are more likely to contain jeux-partis with invention. Of the nine melodies in T, only one (RS 1293) is in group 3.Footnote 101 Seven fall in group 1, suggesting that T represents a group of poet-composers – among them Guillaume li Vinier, Gillebert de Berneville and Thomas Erier – who made particular use of the technique of invention. Manuscript a also features prominently in group 1, a fact that is unsurprising, given that a transmits the most jeux-partis with music notation. There are seventy-six melodies in Appendix 2 that are transmitted in a: twenty-five of these (32.9%) fall in group 1. Notably, few melodies in a have neither invention nor division: of the fifty-five melodies in this category, only sixteen come from a. Chansonniers V and W tell a different story. Neither features much in group 1, where one melody comes from V and two melodies from W. Both manuscripts are represented more numerously in group 3, where five melodies are found only in V and nine only in W; this may indicate that V and W transmit stylistically unusual melodies.

The collection of jeux-partis by Thibaut de Champagne, many of which are contrafacts of grand chant, fall largely outside group 1.Footnote 102 Thibaut’s jeux-partis are often copied together in the sources. The only one of these to be found in group 1 is Sire, ne me celés mie (RS 1185); RS 294, also by Thibaut and in group 1, is unusual in that it is not copied in the Thibaut group in KNX. All of Thibaut’s other jeux-partis are in group 2 or 3.Footnote 103 Other jeux-partis not by Thibaut that are contrafacts of other songs also fall outside group 1.Footnote 104 Given that most of the models for contrafact jeux-partis by Thibaut and others are courtly love songs, the notable absence of these melodies from group 1 could suggest that melodies for the courtly chanson often did not follow the melodic process of invention. An examination of the entire grand chant repertory, which is beyond the scope of this study, would be necessary to prove such a hypothesis. The absence of contrafact jeux-partis from group 1 also means that the presence of invention in melodic structure would appear to be a uniquely Arrageois phenomenon.

Invention and division are not restricted to melodies in pedes-cum-cauda form: seven of the forty-one melodies (17.1%) in group 1 are through-composed; in group 2, nineteen of the sixty-three melodies (30.2%) are through-composed; in group 3, twenty-two of the sixty-four melodies (34.4%) are through-composed. Melodies that are through-composed are therefore more likely to lack invention, but this is not a fast rule. Where through-composed melodies demonstrate invention to a high or mild degree, the initial material on which subsequent sections of the melody can be based is either introduced in the first two lines of the song, or in the first four lines. In the group 1 melody Sire Michiel, respondés (RS 949), for example, the melody is ‘found’ in lines 1 and 2 and then revisited in the remainder of the melody (see Example 9).Footnote 105 Lines 3 and 4 expand on line 2. Line 5 returns to the start of line 2 to introduce the first side of the dilemma (whether a true lover should know the heart of his lady or that his lady knows his desire) with the conjunction ‘ou’. The second ‘ou’ is stated at the start of line 7, where the melody returns for the first time to the melodic material of line 1. The second part of the melody (lines 3–8) is closely modelled on melodic material ‘found’ in the first stage of invention in lines 1 and 2. Important moments of division in the text (two statements of ‘ou’) are matched in the melody by returns to significant melodic moments – either material from the start of line 2, where the metapoetic term ‘jeu-parti’ is first heard, or material from the song’s opening. Formal repetition of whole lines, such as one finds in pedes-cum-cauda form, is thus not a prerequisite for invention or division.

A note of caution to end this study is perhaps prudent. In searching for invention and division in the melodies of jeux-partis I have been optimistic in my analyses, asking whether a melody can be understood through the lenses of invention and division. Some analysts may not hear invention or division as strongly in some of the melodies of group 1 and group 2, and may question whether these jeu-parti melodies, with their relatively narrow ranges and mostly conjunct motion, can be explained just as well without recourse to concepts of invention or division. But that is perhaps the point. In a social context where intellectual rigour was valorised, and where processes such as invention and division were paradigmatic, I contend that poet-composers and listeners would have listened out for and appreciated the subtle ways that trouvères performed invention and division through their use of melodic structure. The social significance of both invention and division is clear from the use of metapoetic terms – occasional for trouver and frequent for partir – through which poet-composers drew particular attention to their performances of meaning. In their self-conscious employment of invention and division, poet-composers of the jeu-parti curated authorial positions that were intellectual, prestigious and combative, commensurate with their cultural environment of Arras and the shift towards more clerkly modes of authorship during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.Footnote 106

University College Dublin

Instances of ‘Trouver’ or ‘Partir’ in Jeux-partis

Trouver:

Only uses of ‘trouver’ that refer to an act of composition are included. Songs are indicated by their RS number.

899

1191

Partir:

Only uses of ‘partir’ that mean ‘division’ or ‘divide’ have been included. * indicates that ‘partir’ is used to open the first stanza. Songs are indicated by their RS number.

Prevalence of Invention and Division in Jeu-parti Melodies