It is saidFootnote 2 that in the days that Bahlūl Khān was Governor of that town (Sirhind or Sihrind)Footnote 3 he had built outside the fort a mansion comparable to the heavenly paradise. Sometimes he resided there. In those vicinities lived a goldsmith who had a daughter called Hīmā, with a face like a tulip and hair the colour of musk; it happened that Bahlūl's eye fell upon her, he was enchanted. That beauty with moon-like face also gave her heart to him. When he sat on the royal throne he satisfied the wishes of her father and married her. One day that girl dreamt that the moon became detached from the sky and fell into her bosom. The next day she told her dream to King Bahlūl. When he asked its meaning from the interpreters and the Hindu priests (kāhinān),Footnote 4 the hair-splitting interpreters opened the heart of the matter: that from the womb of this Queen of the World a son would be born who would gain the throne and would own the crown.

The Tārīkh-i Shāhī’s record of the name HīmāFootnote 5 is curious as it is not a Muslim name, but is the Persian way of writing the Sanskrit hema (heman: gold, apparently a translation of the Persian zarrīna), and this is perhaps what the non-Persian-speaking people called her. The Bībī’s name is recorded variously in different sources. At Dholpur,Footnote 6 where she is believed to have been buried, she is known as Bībī Zarrīna (The Lady of Gold). Her name on her tomb is now partly eroded, but in 1885 Cunningham,Footnote 7 who saw the inscription when it was better preserved, confirmed the name as Zarrīna. Historical sources, however, differ; her name, or perhaps honorific, is recorded in Firishta's Persian text as Zībā (beautiful),Footnote 8 and in Briggs's translation as Zeina (Zīna, Zīnat: ornament, by extension also meaning elegance, beauty).Footnote 9 Zīnat (زینة) could be a misspelling of Zarrīna (زرّینه) simply omitting the letter “r”, and as she is known to have been the daughter of a goldsmith (zargar),Footnote 10 while we may consider both texts to be slightly defective, both Zarrīna meaning “made of gold”, and Zeina (Zīnat) meaning “ornament or jewellery” would be suitable for a goldsmith's daughter. In Islamic India it is unusual for the proper name of a woman, particularly a queen and the mother of a king, to be given in a historical text. In fact many of the sources omit mentioning the name of Sikandar's mother altogether. If she was referred to, it would be usual for a descriptive honorific to be employed, and in this case we may assume that all recorded names, including Zarrīna would have been honorific. Those used all reflect appreciation of her beauty, and give revealing insights into her background and how the populace perceived the unseen mother of the king.

The son foretold by “the Hindu priests and the hair-splitting interpreters” was, of course, Sikandar, who apparently inherited his mother's looks:Footnote 11

Sikandar Lodī … in the days that he was a prince was called Niẓām Khān. By the Almighty Lord he was adorned with exceeding elegance and beauty as though the painter of destiny had not drawn a face more pleasant than his on the tablet of life … whoever saw him lost his heart to him.

The Tārīkh-i Shāhī continues with the affair of Shaikh Ḥasan's unrequited love for the Prince. Ḥasan, known as Shaikh Ḥasan Majzūb (the enchanted), was a grandson of Shaikh Abu'l-ʿAlā and a highly respected religious personage.Footnote 12 To quash the rumoursFootnote 13 of the Shaikh's forbidden love, the young – probably beardlessFootnote 14 – prince, in his own court and with others present, punished the Shaikh by putting his face into a hot brazier and then locking him up, although he was seen “miraculously” walking in the bazaar the next day.

Sikandar's mother was by no means a voiceless lady of the harem. Her son was not Bahlūl's eldestFootnote 15 and had many adversaries. In the final days of the sultan's life she made sure that Sikandar remained in Delhi, safe from the machinations of the Lodī clan who wanted to eliminate him and had made the sultan summon himFootnote 16 to Itāwa.Footnote 17 She heard that the most powerful emirs had resolved to make Aʿẓam Humāyūn, the sultan's grandson, the crown prince and that the ailing sultan had agreed. Colluding with ʿUmar KhānFootnote 18 – a prominent army commander who also held the position of vizier – she sent a messenger to Sikandar informing him that his life would be in danger if he came to the camp at Itāwa. Her son whiled away the time on the pretence of preparing for his journey, until Bahlūl died while en route to Delhi.Footnote 19

On the death of Bahlūl in 894/1489 most nobles of the Lodī clan disapproved of Sikandar, but it was his mother, supported by Khān-i Khānān Farmulī – one of the most esteemed of Bahlūl's courtiers and responsible for Sikandar's upbringingFootnote 20 – who confronted the other nobles:Footnote 21

When according to the Decree of the Unfathomable Most Powerful, King Bahlūl LodīFootnote 22 received the Mercy of the Lord during the mentioned journey, the emirs and pillars of the state gathered, opening the topics of discussion. Some favoured Aʿẓam Humāyūn, the grandson of the late king, but most preferred Bārbak Shāh, the eldest of the living sons, for king. At this time Sultan Sikandar's mother, Zībā by name, who was the daughter of a goldsmith and was accompanying the late king, called to the emirs from behind the curtain saying: “My son is the one who is fit to be king and would treat you well”. ʿĪsā Khān Lodī, who was a nephew of Sultan Bahlūl, belittled her saying “The son of the daughter of a goldsmith is not fit to be a king, so says the well-known proverb that a carpenter's work will not come out right done by a monkey”.Footnote 23 Khān-i Khānān Farmulī, who was a powerful person, on hearing this retorted: “Yesterday the king died and today how can it be proper to use vilifying defamatory words against his wife and his son?” ʿĪsā Khān Lodī replied: “You are no more than a servant! Do not interfere with the family and relatives!” Khān-i Khānān became angry; declaring: “I am the servant of King Sikandar and no one else” and left the assembly. He came to the emirs who were allied to him, took the king's corpse and went to the village of Jalālī, then sent for King Sikandar and put him on the royal throne on the heights by the River Āb-i Bīyāh in the place called the Mansion of Sulṭān Fīrūz.Footnote 24 They named him Sulṭān Sikandar.

Sikandar was enthroned on 17 Shaʿbān 894/16 April 1489Footnote 25 and during his reign focussed on consolidating his sultanate and eliminating the vestiges of the Sharqīs, while being under constant threat from the south, particularly Gwalior. To achieve undisputed control, in 897 he finally put a permanent end to the semi-autonomous rulers of Bayana, and made Khān-i Khānān Farmulī governor of the region, with the aim of securing the border with Gwalior.Footnote 26 Khān-i Khānān kept the southern borders firm until his death in c. 906/1500–01, when the sultan assigned BayanaFootnote 27 to his two sons, but an uprising instigated by Manakdev among the Hindus forced these sons to retreat, and Sikandar took over Dholpur, rebuilding the fort in 910/1504.Footnote 28 A year later Sikandar seized on the opportunity of campaigning against Gwalior, initially without complete success, causing him to set up camp in Bayana, where he toyed with the idea of making it his new capital, but in 911/1515–66 decided on Agra.Footnote 29 From this time on Sikandar Lodī spent most of his time in Agra and in Dholpur, which had finally been carved out of the territory of Gwalior. Not only was control of Dholpur vital to keep Gwalior in check, but also it seems that the sultan favoured the town for his residence,Footnote 30 and for many months at a time stayed there, building palaces, other buildings and gardens at every stage between Agra and Dholpur.Footnote 31

During the sultan's extended stays in Dholpur his mother, the senior lady and authority in his harem, would have been residing with him, particularly when we consider that in younger days, travelling with her husband Bahlūl, she was not of a retiring disposition. It is, therefore, plausible to consider that she might have died in Dholpur, although as usual the histories are silent about the sultan's private life. For the last few centuries, and probably since the Lodī era, the tomb and mosque compound in the graveyard has been attributed to her and while there are other tombs of the Mughal period and a sizeable Mughal step-well nearby, probably from the time of Jahāngīr, the most impressive structure is that of Bībī Zarrīna, whose identity as the mother of Sikandar Lodī is also endorsed by Cunningham.Footnote 32 The scale and elaborate design of the monument also indicates persuasively that it must belong to a noble lady.

There are a number of inscriptions in the complex, some carved in relief over the miḥrābs of the mosque, while eroded or intentionally obliterated, seem to be of a religious nature and might not have included dates, but the inscription of the tombstone of the Lady, again suffering from erosion and obscured by layers of whitewash, is slightly better preserved.Footnote 33 What can be deciphered is, on the headstone, the beginning of Quran II, 255 (āyat al-kursī) continuing on the right side and with the end of the verse on the left side, followed by what seems to be Quran XXIII, 118:Footnote 34

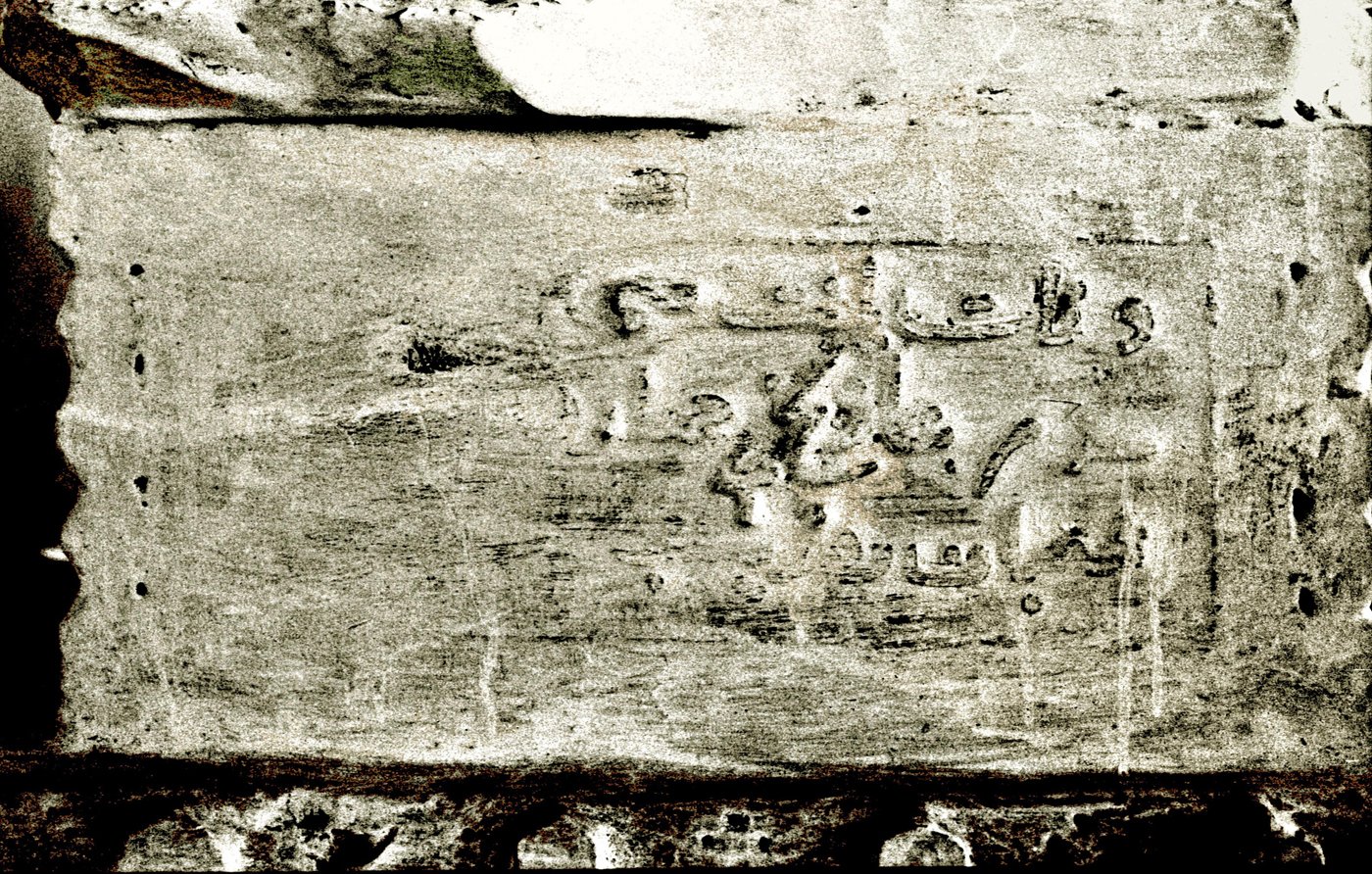

On the foot of the tombstone is the historical record (Figure 1), badly damaged, and what remains from it is:

Figure 1. (Colour online) Dholpur, the historical inscription of the foot of the Tomb of Bībī Zarrīna. The eroded text bears part of her name and the date of her death, probably Sunday 14 Shaʿbān 922/12 September 1516.

The letters within square brackets are no longer preserved and reconstructed from a rendering – not an ink impression, which is more reliable for deciphering – by Cunningham (Figure 2), when the inscription was still in better condition, although we do not know to what extent it was preserved. At present no traces are left even of the name Zarrīna, but if Sikandar's mother was called Zībā, Zaina (pronounced Zīnat (زینة) in Persian), the letter represented as r in Cunningham's rendering which makes the name zarrīna may well have been the diacritic representing the vowel a over the letter z, confusing the name with Zarrina. Zaina or Zīnat are still current women's names in Iran and elsewhere. Nevertheless we should perhaps trust Cunningham and others, as well as the local population, for the name.

Figure 2. Cunningham's rendering of the inscription of the Tomb of Bībī Zarrīna. The epitaph was in better condition when read by him (ASIR, XX, 1885, pl. 37).

In Cunningham's rendering the figure for the decade is clearly close to the Arabic numeral two, making the date 922 (٩٢٢), but he reads the date as 942 (٩٤٢) presumably to square up the reading of the date of the month with a year when that date fell on a Sunday.Footnote 35 The date of the Bībī’s death, however, is noted in the Rajputana Gazetteer Footnote 36 as 922, presumably taken from this inscription. We can, therefore, safely assume that the reading of 922 is more reliable. If we accept this, she would have been in her eighties when she died.Footnote 37 Sikandar himself died a year later and was buried in Delhi,Footnote 38 in a tomb octagonal in plan with arches and domes much in the style of his predecessors, the Sayyids.

Dholpur, 35 miles (56 km) south of Agra and 20 miles (32 km) north-west of Gwalior was historically a small town in the territory of the Rajas of Gwalior,Footnote 39 coming under Muslim control only at the time of Sikandar Lodī. The Bābūr-nāma mentions Sikandar's dam, forming a great lake, as well as a garden there, presumably from the time of the sultan, and that Bābur ordered a seat and four-pillared platform (talar, apparently a four-columned chatrī) to be carved out of solid rock on the east of the lake, and a mosque on the west.Footnote 40 The Ā’īn-i Akbarī records that when Agra was made the capital, Dholpur was one of the six districts which was taken out of the Bayana region and incorporated into the newly created region of Agra.Footnote 41 With Muslim domination of the area, Dholpur's strategic importance increased, and while Sikandar Lodī built Agra as his capital, ongoing strife with Gwalior obliged him to reside in Dholpur for prolonged periods.Footnote 42 The Ā’īn-i Akbarī also records that Dholpur had a brick fort on the bank of the Chanbal.Footnote 43 The fort was indeed an old Hindu stronghold, which was apparently maintained and restored by the Lodīs and later reconstructed by Shīr Shāh Sūrī. Its ruins, named after Shīr Shāh, are now known as Shirgarh.Footnote 44 Apart from the tomb of Bībī Zarrīna hardly any monument dating prior to the Mughal period has survived there, but the town and its immediate vicinity preserve a number of fine Mughal and post-Mughal structures, including the Khanpur Maḥal and Shāhī Tālāb, both known to have been built by Shāh Jahān.

The mosque and tomb compound

The Dholpur tomb and mosque, built on a high platform, are entirely of red sandstoneFootnote 45 and built in the trabeated structural method typical of architecture of the Bayana region. Unlike the Sayyid and Lodī buildings of Delhi, deriving from Tughluq architecture and often incorporating arcuate structures set partially on monolithic columns, in the Bayana region all major Lodī buildings, except one, and even those of the early Mughal period, are trabeate.Footnote 46 In Delhi on the other hand, the tombs of the Lodīs are in the style of the Sayyids,Footnote 47 octagonal chambers surrounded by an arcade with multiple chatrīs around the main dome, a form that appeared first in the tomb of Khān-i Jahān Tilangānī,Footnote 48 and continued to be used by the Sūrīs and even in the early Mughal period, such as the tomb attributed to ʿAlā al-dīn ʿĀlam ShāhFootnote 49 a brother of Sikandar Lodī and his Governor of Tijara, who later joined Bābur and died during the reign of Humāyūn, to one of the latest: the tomb of Adham Khān.Footnote 50

The handsome and elaborate tomb of Bībī Zarrīna is a square building on the west of a rectangular courtyard facing the mosque (Figures 3 and 4). Although the platform could house a crypt, the absence of one indicates strongly that the tomb dates from the pre-Mughal era. A unifying design for the complex is expressed in the beam and bracket structure of the mosque and the tomb, but there are subtle differences in detail.

Figure 3. Mosque and tomb of Bībī Zarrīna, ground plan. The complex is set on a prominent platform, but has no crypt. The tomb of the Bībī is in the centre together with six other tombs at the east side of the tomb chamber. The area to the north of the dotted line in the courtyard seems to be a later addition.

Figure 4. Mosque and tomb of Bībī Zarrīna, transverse section A-A through mosque and tomb; section B-B through courtyard, showing elevation of mosque.

The compound is within a graveyard (Figure 5), and entered from the north, via steps and a modern gate with a semi-circular arch opening to the paved courtyard.Footnote 51 The mausoleum is a square chamber consisting in plan of nine square unitsFootnote 52 formed by 16 columns supporting a flat roof with slabs set directly on the lintels, except for the central unit where over the lintels are four triangular corner slabs and a further layer above formed of short lintels and triangular blocks, creating an octagon to support the flat roof slabs (Figures 3 and 6). The floor of the central unit, housing the tomb of the Bībī, is raised slightly in the form of a low platform decorated with mouldings. The columns are plain, but pierced stone panels (jālī) are inserted between the exterior columns. The jālī screens are divided into six panels of almost the same size, except the middle of the western and southern sides where doors open to the tomb, each with an arch above, carved on a single panel as delicate pierced work, flanked by jālī panels. A variety of interlaced patterns are employed in the carved screens, giving a particular charm to the interior when light penetrates the screens and shadows of the patterns fall on the floor and the tombs.

Figure 5. (Colour online) Mosque and tomb of Bībī Zarrīna, southern façade. The severely dilapidated rear wall of the mosque can be seen on the left. The tomb in the foreground with a “Bengali” roof dates from the late or post-Mughal era.

Figure 6. (Colour online) Tomb of Bībī Zarrīna, interior. View looking north-west showing the fine pierced stonework (now whitewashed) surrounding the cenotaph, and the raised roof over the Bībī’s tomb.

In the middle of the building the tombstone of the Bībī (Figures 6 and 7) is in the form of a grand solid sarcophagus in several registers standing on a base with a cyma recta profile embellished with lotus leaf motifs, an ancient Indian pattern, also employed in Muslim buildings, but which hardly appears in Mughal architecture. This is another indication that the tomb is pre-Mughal. Above this base is a long and narrow register decorated with an interlaced pointed arch pattern, but many layers of whitewash make this and other carvings hardly visible. The register is topped with a row of triangular mouldings, probably a highly stylized reminiscence of the vajramastaka, which adorned the parapets of ancient temples. The middle block bears the already noted Quranic and historical inscriptions and the top two registers are stepped and have the same row of triangular ornament and are topped with a flat slab. There are six other tombs in the chamber, three similar in form to that of the Bībī, but slightly smaller and less elaborate. While none of the other tombs bear historical inscriptions, they must belong to her relatives. The elaborate form of the sarcophagi is not specific to these tombs and is seen in many of the more ornate tombstones of the Bayana region. Two of particular relevance here are of ladies, both in Hindaun (a historic town near Dholpur): that of Bībī KhadījaFootnote 53 and of Bībī Rāsūlī.Footnote 54

Figure 7. (Colour online) The sarcophagus of Bībī Zarrīna. View of the right side showing courses of decoration including the lotus leaf motif on the lower register and a course of lobed arches below the inscription which bears part of the Throne Verse (Āyat al-Kursī) of the Quran. Above the inscribed panels are rows of triangular motifs.

On the outside, the narrow columns and even thinner screens, give a sense of lightness to the well-proportioned chamber (Figure 8). At roof level the parapet above the eaves consists of two string courses, the lower carved with interlaced lobed arches within each of which is a bell-shaped floral motif. A simplified form of this motif is repeated on the narrower upper course. Above the parapet the crenulations, each carved on a separate panel, are in the form of a solid arch with a wide border and a central rosette. The most prominent feature on the exterior is a four-columned domed pavilion or chatrī set on on a raised platform over the central unit of the structure (Figure 9).

Figure 8. (Colour online) Tomb and mosque of Bībī Zarrīna, view looking south-west. The central chatrī stands over the tomb. The compound is designed in such a way that each structure stands on its own and does not conflict with the other; as a result from the east the tomb stands alone and the mosque can hardly be seen in the background.

Figure 9. Tomb and mosque of Bībī Zarrīna, plan at roof level. The unusual roof colonnades with four domes and the chatrī over the central miḥrāb echo the central chatrī of the tomb.

There are precedents for chatīs on the roofs of buildings. Although colonnaded structures appear in Hindu architecture, chatrīs on roofs seem to derive from Iranian and Central Asian wooden canopies, often covered with textiles and illustrated in many Persian miniatures. The existence of such canopies in the early Sultanate period is recorded by Ibn Baṭṭuṭa, and the sockets of probable wooden supporting columns have survived on the roof of the Bijai Mandal,Footnote 55 the palace of Muḥammad ibn Tughluq in Delhi. The feature, transformed into stone, appears at least from the time of Fīrūz Shāh Tughluq; an early example in Delhi is over the mosque at Qadam Sharīf,Footnote 56 but they also appear on the roofs of Lʿal Maḥal,Footnote 57 Jahāz Maḥal,Footnote 58 and on the corners of the platform of the tomb of Daryā Khān Lohānī.Footnote 59 However, a better example, near Dholpur, is the tomb known as Baṛe Kamar outside Bayana.Footnote 60

In the tomb of Bībī Zarrīna the design is expressed not in the intricate detail, but in the boldness of the structural form. Nevertheless, the column shafts, octagonal in the middle and square at each end, stand on cubic bases and footings with cyma recta profile. The shafts are of a type seen commonly in Bayana and other towns of its region. The crenulations of the chatrī, although similar in shape and proportion to those of the tomb, are not individually formed, but are carved on four panels, each set on one face, a treatment repeated in many chatrīs of the region.

Unlike the light structure of the tomb, the mosque, set at the west of the courtyard, has solid walls about 1.60 m thick, contrasting with the mausoleum from outside (Figures 10 and 12). The mosque is a simple prayer hall, two aisles deep and five bays wide, with the two side bays narrower than the rest (Figures 3 and 4).Footnote 61 The column shafts are rectangular in plan, but the size of the narrow sides facing the courtyard corresponds with those of the tomb, retaining a fine aesthetic balance between the two structures while preserving contrast. On the qibla wall (facing the direction of Mecca) are five miḥrābs (prayer niches), with pointed arches, resembling the pierced stone arch-forms above the entrance of the mausoleum, but built in solid stone (Figure 11). Nevertheless, a balance harmonizing with the lattices of the jālī work of the tomb is maintained by the inclusion of interlaced foliated fringes and geometric tracery in the field of the arches similar to that of the screens of the tomb.Footnote 62 The delicate interlaced foliage pattern seen here is an elaborate variation of the spearhead fringes seen in many Muslim monuments in India as early as the fourteenth century. On the exterior only the central miḥrāb projects outside the wall.

Figure 10. (Colour online) Mosque of Bībī Zarrīna, view from west. The solidity of the plain sandstone qibla wall of the mosque, and on the roof an arcade (which originally had jālīs) and the chatrīs, complement the lighter and more delicate tomb. Again the design is such that from the west the mosque appears as a massive structure and obscures the view of the tomb.

Figure 11. (Colour online) Mosque of Bībī Zarrīna, view from the courtyard looking west. The crenulations reflect the pattern of those of the tomb, but those above the front façade are carved on panels and those of the upper colonnades are each carved on a separate slab. The game of similarity and contrast between the tomb and the mosque is maintained in every detail.

Figure 12. (Colour online) Mosque of Bībī Zarrīna, the prayer hall. The miḥrābs and lamp niches are carved to reflect the patterns of the screens of the tomb. The whitewash highlighted with black paint is modern, as is the painted calligraphy.

Within the northern and southern walls of the prayer hall are two staircases ascending to the roof, accessing two colonnades five bays wide and one aisle deep stretching the whole width of the hall. The backs of the colonnades are walled with light stone panels, those at each end carved as jālīs, but some are broken and others replaced with plain panels. These colonnades, peculiar to this structure, are most unusual for the roof of a mosque and do not appear elsewhere. The buildings of the Bayana region often depart from the norm in form and function, and apart from the practical use of the roof as a place for the Caller to Prayer to recite the adhān, the colonnades would have provided a pleasant shady retreat. They also create a strong contrast to the tomb, but, again to harmonize the two buildings, four small domes punctuate the corners of the composition, and a four-columned chatrī is set over the projection of the central miḥrāb.

The composition as a whole plays with contrast, leading the eye from one feature to another. The modest scale of the compound also seems intentional, as it suits the mother of a king, leaving the grander design for the tomb of the sultan himself. But there may have been another reason for the chosen scale. If the mausoleum were much larger it could not have been as light as it is and the balance between the size of the building and the finely carved screen work would have been lost. As it is, the chamber with its delicate jālī work (Figure 13) appears as an enlarged version of an ornamental box – a jewel box – of a type that used to be carved in ivory and are still fashioned in fine woods such as sandal; a suitable form, perhaps, for the daughter of a goldsmith, and within it the jewel – the mortal remains of the “Golden Bībī”.

Figure 13. (Colour online) Tomb of Bībī Zarrīna, view from the courtyard looking east. The delicately carved red sandstone would have appeared like the carvings of a precious rosewood or sandalwood box.