For a long time to come, historians will be exercised by what really lay behind the challenge of the Brexit referendum of 23 June 2016. The politics were certainly shoddy, but the result was not just some unfortunate blip. Economic, sovereignty, social and societal factors were all important. The result also revealed a protest vote that was full of fear, especially about immigration. While certainly not arguing for a mono-causal explanation, I will here explore one factor, the UK’s imperial and post-imperial inheritance since the Second World War, and ask how this has shaped its thinking about post-war continental integration.

Brexit is a reminder of the UK’s historical reluctance to make a wholehearted commitment to continental Europe unless under pressure. It reflects geopolitical positioning but also the UK’s imperial political culture, ideas and identity, even as its vast global empire slipped away. Now, amongst EU members the United Kingdom seems uniquely burdened by its imperial inheritance (although there may yet be spoiler alerts for other member states). We see the Leavers’ obsession with the idea of the UK’s continuing international leadership characterised by the so-called ‘Anglosphere’, the Commonwealth, a desire for sovereignty, for a go-it-alone autonomy with non-specific hostility to some immigrants and an attachment to sterling. These seem to be the cultural markers for British nostalgia, although those in favour of leaving the European Union have not yet constructed a coherent new strategy for the country. The irony of all this is the more marked, as the UK has actively encouraged, and indeed still encourages, the post-cold war states of Eastern Europe to make their own massive cultural and political shifts after communism and to reimagine themselves as members of a democratic EU.

In 1945 the UK had not been invaded or defeated in war, unlike its continental neighbours. Its hard-won victory left a legitimate pride in a legal and constitutional system that had survived the war, and a belief in the UK’s obligation to lead others and as part of this, to construct its own nuclear force as a marker of being at the ‘top table’. The UK could also balance power on the post-war continent in part through the military occupation of defeated Germany, and all this despite its own recurring national economic crises. A new global international system was now being constructed, and ideas were also being explored about creating a new regional order that might render yet another European war impossible. The British and Americans played a leading role in the creation of a post-war global international institutional order that still remains today. The UK’s own role was amplified through its membership in these international institutions, and other European states genuinely sought UK leadership in the 1940s. Yet from the mid 1940s onwards a violent dismantling of the vast British Empire was also underway, in India, Ceylon, post-mandate Palestine, Malaya, Africa and the Gulf. The UK was left with a national narrative based upon the image of a seafaring island with imperial outposts, and with close and special ties with the developing Commonwealth and the United States through culture, language, sterling and economics.

Is it possible to pinpoint a moment in this complex double process of decolonisation, and the building of a new world and European order, that helps us to understand 2016? I suggest that the years between 1948 and 1951 represent such a turning point. Decisions about a European or Empire/Commonwealth tilt in UK foreign policy, supranational institutions versus inter-governmental cooperation, domestic politics, project leadership, national autonomy, Anglo-Saxon values and the continental balance of power all came to a head during these critical years of decision making.

Even as the United Nations, International Monetary Fund (IMF) and General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) were being created, and Cold War thinking about bipolarity came to dominate politics, by 1948 efforts to create a quasi-federal decision making system for the implementation of the US’s Marshall Aid package in Western Europe were stalled by the British. The UK demanded consensus decision making and bilateral relations on the issue became very testy, leading the Americans to think their plan’s wider European integrationist and quasi-federal strategy was actually failing. By the autumn of 1949, after the North Atlantic Treaty was signed, the United States turned instead to France for continental leadership.

At the same time the effectiveness of the 1948 Council of Europe quasi-federal initiative was stalled by the UK’s insertion of an intergovernmental Committee of Ministers into the structure, so neutering the Council at birth. Then the UK only grudgingly accepted the Council’s Convention on Human Rights, arguing that the British constitutional and legal system did not need to be refined by any continental European court, and that this would bring huge problems relating to its unequal legal regimes in colonial territories (they were correct).

Then, in May 1950, the Franco–West German Schuman Plan for the joint control of coal and steel industries (the drivers of war) was proposed, spearheaded by the policy entrepreneur Jean Monnet. This was the key moment, the parting of the ways. It marked the beginning of the Western European supranational integration movement and shaped the future European Economic Community (EEC) and EU. There was also pique in London about the Schuman Plan, as the Americans had been told about it before London – a bad tactical decision in Paris. The personality mix really mattered, then as now. The British scholar-politician Edmund Dell later claimed that 1950 was the moment the UK lost the leadership of Europe. He could be right. British reasoning at the time reveals a raft of assumptions during the crisis decision making period, some of which we can see again today. The plan did not fit with Labour’s vast domestic programme of nationalisation – so the ‘Durham Miners won’t wear it’ domestic politics was key. The plan required a commitment to joint, supranational management even before any detailed procedures were fleshed out. After unsuccessfully proposing association, or even advisory, inter-governmental ways forward for coal and steel production, The UK rejected the Schuman Plan. Winston Churchill, then leader of the Conservative Opposition, was happy to stir up dissent by suggesting the Labour government had misjudged the situation. No major UK political party was then, or ever after, an unequivocal supporter of European supranational integration.

In the same year, as the Pleven Plan for Franco-German integrated armed forces was also rejected out of hand by the UK, the Foreign Office began to synthesise the UK’s attitude to continental integration. Supranationality developed by France to control a recovering West Germany was acceptable. If France succeeded, the challenge would then just be to keep the EEC firmly nested within the NATO/Atlantic Community, backed by notional inter-governmental European defence agreements (Brussels Treaty, 1948/Western European Union, 1954). The UK could still pursue its global role. Then, as now, ‘Association’ was the favoured British response – the ‘with, not of’ route that was taken from 1954, and then from 1956–9, with free trade area solutions to include the Commonwealth and dilute the EEC. (This also sounds familiar). A key 1951 Foreign Office document is worth citing. Its superior tone is perhaps of a different era but it resonates today.

Apart from . . . Commonwealth ties and the . . . sterling area, we cannot consider submitting our political and economic system to supra-national institutions . . . if these institutions did not prove workable, their dissolution would not be serious for the individual European countries which would go their separate ways again; it would be another matter for the UK which would have had to break its Commonwealth and sterling area connexions[sic] to join them. Nor is there, in fact, any evidence that there is real support in this country for any institutional connexion with the continent. Moreover . . . it is not in the true interests of the continent that we should sacrifice our present unattached position which enables us, together with the United States, to give a lead to the free world. (Documents on British Policy Overseas, Series 2/1, (HMSO, 1986), PUSC (51) 12)

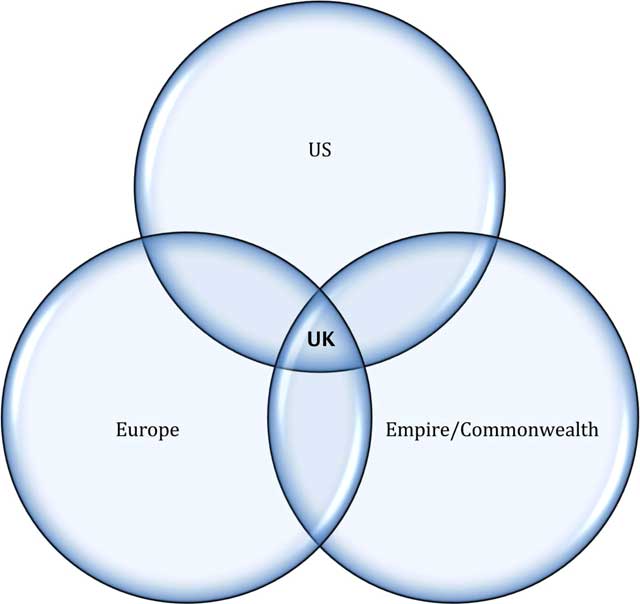

This extraordinary document was in essence a policy implementation of Winston Churchill’s famous ‘Three Circles’ party conference speech of 1948, which set the framework for strategic thinking about the place of the UK in the world, and which has had enormous persistence over time as the single most important strategic statement about the UK in the post-war era. The UK, Churchill argued, was the only country at the centre of the three great interlocking circles of Europe, the United States and the Empire-Commonwealth. A British commitment to one circle alone would destroy the whole structure of the free world and its ability to fight communism. The argument was that the UK’s international leadership could only be guaranteed by sustaining its pivotal balance between the three circles. (Figure 1).

Figure 1 ‘The Three Circles’

Yet the UK had failed to grasp the game-changing diplomacy in Europe. It was France that became the continental leader. By 1950 it had seized the initiative and ingeniously used the Schuman Plan, and then in 1956 the EEC, as substitute loci for French power in Europe. France, too, was decolonising, but it was to commandeer the EEC as the basis for a French dominated post-imperial ‘Euro-Afrique’. By the late 1950s French President Charles de Gaulle well understood the UK’s strategic-cultural decisions about continental European integration, its own mission and culture, its own worldview and the error of judgment that it had made. He had no compunctions about now unilaterally keeping the UK out of the European project with his three vetoes of the UK in 1958, 1963 and 1967, despite British belated efforts to turn the tables, redesign the project or just simply scramble on board.

So the UK was the first supranational integration refusnik, then a late joiner of the EEC. Over time, it became the EU’s currency and border control ‘opt-outer’ par excellence, as the post-cold war EU emerged in the 1990s. British politics generated no consistently pro-integration political party at home. The self-regarding ambivalence of 1948–51 had left the UK continuously glancing over its shoulder to the United States and the wider, post-imperial Commonwealth world. It had become the ‘awkward’ transactional partner.

Much has of course now changed, yet the lingering ideas of an imperial political culture that is greater than European commitments have not fully been shaken off. The passionate resignation letter of former foreign secretary Boris Johnson (a one-time biographer of Churchill), argued that continuing to accept aspects of EU law while only half-out of the EU (‘soft Brexit’) was dithering and would be a ‘ludicrous position’, meaning ‘we are truly headed for the status of colony’. Note the language used, as is the case for ‘Empire 2.0’, which was reportedly widely used within the Liam Fox’s Department of International Trade, or aspirations for a CANZUK (alliance between former Dominions Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom); as well as the later use of the words ‘diddly squat’ and ‘vassalage’ to describe the future for the UK without a clean break from the EU.

The long ending of empire left successive British prime ministers of both parties with a belated quest to refocus British post-imperial leadership and to steer the EC/EU. This will of course now end. But neo-imperialism, Churchill’s three circles or ‘Empire 2.0’ outside the EU are not serious propositions. The government has not said what the sunlit uplands may look like beyond aspirations for global entrepreneurial leadership, free trade deals and greater bilateralism in foreign policy for a new ‘global Britain’. British politicians still use the ‘leadership’, ‘global leadership’ and ‘national interest’ catchphrases like some post-imperial default button. It is also very significant that Northern Ireland and Gibraltar are now both trapped on this hideous crossover of the UK’s post-imperial and European policy frames and remain deeply intractable diplomatic Brexit issues. The Windrush victims are likewise also caught in the fangs of a constructed, hostile and unresolved environment towards immigration generally.

Does this all matter, apart from the loss of UK national prestige and the economic dangers that lie ahead? Yes it does. At crucial moments historians can see the past through a new lens – and Brexit is just such a lens. States can be the positive builders of the international system: the UK was a positive builder of a new international system until presented with the dilemma of supranational integration and the French leadership challenge that could undermine its own imperial and Commonwealth role. But states can also be destructive: for as you pull out one thread from the fabric (Brexit), you alter and can weaken the rest of the international order. This includes both the EU and NATO. The Commonwealth, too, is vulnerable to unravelling. International institutional unravelling could be one consequence of events, not least given changes in the United States, and although the UK Conservative Government promised to continue the rule-based order, this is now effectively under challenge.

Explanations of the 2016 referendum lie in part, and of course only in part, in the UK’s lived and remembered imperial past. Churchill’s three circles had fallen away by the 1960s, but it seems to be the case (think ‘having your cake and eating it’) that some Leavers yet dream of some twenty-first century version. Yet Brexit will not in reality empower politicians to reconstruct a reimagined global past, while nostalgia provides only weak signposts for the future, beyond hubris.