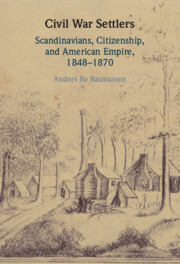

What Walt Whitman called the “volcanic upheaval of the nation, after that firing on the flag at Charleston” prompted a meeting in New York’s Scandinavian Society in April 1861.Footnote 1 The meeting helped organize the first Scandinavian company in the Civil War and incorporate it into the First New York Infantry Regiment.Footnote 2 Company recruits elected Norwegian-born Ole Balling as captain, Danish-born Christian Christensen as first lieutenant, and Swedish-born Alfred Fredberg as second lieutenant. Both Balling and Fredberg had experience from the First Schleswig War in 1848, and Christian Christensen, the Scandinavian Society’s president and the recruitment meeting organizer, seemed a natural selection, since he was “well-known among all Scandinavians in America” (see Figure 5.1).Footnote 3

Figure 5.1 Christian Christensen, president of the Scandinavian Society in New York and Civil War officer, photographed in New York early in the war.

With the Scandinavian Society’s host J. A. Jansen “chosen as First Sergeant,” the company’s leadership, representing the three Scandinavian countries, reflected the general composition of the unit. “The company now consists of approximately 80 Scandinavians evenly divided between the three countries,” the unit’s librarian reported back to the Copenhagen paper Dagbladet (The Daily).Footnote 4

Before embarking for Newport News in Virginia on May 26, 1861, the company received a battle flag from the Swedish ladies in New York and a drum from a local Danish-born attorney, while also participating in a parade down Broadway with the rest of the First New York Regiment.Footnote 5 Shortly after arriving in camp by Fort Monroe, the First New York, along with several other New York regiments, saw action at the battle of Big Bethel. The June 10 engagement ended in a Union defeat; it also prompted several letters to New York newspapers and family members back home.Footnote 6 In a letter to his mom, Danish-born Wilhelm Wermuth stressed that he had thus far escaped unscathed, but he also admitted, “I have been near our Lord a few times, I was in a pitched battle on June 10 and a man fell close to me.”Footnote 7 About the war’s larger implications, Wermuth added: “Now we await a big battle by Washington which will presumably settle the fate of the blacks.”Footnote 8

The topic of slavery was also important in public statements about enlistment, though reality, perhaps not surprisingly, proved more complex. In a letter dated August 22, the Scandinavian company’s librarian recounted the battle of Big Bethel in Dagbladet and attempted to put the soldiers’ motivation into words. According to the Scandinavian-born letter writer, the men greatly desired to “meet the enemy in open battle,” since they had volunteered not out of “ambition or greed or other ignoble motives, but to defend and assert freedom and all human beings’ equal entitlement thereto, regardless of how the skin color varies.”Footnote 9

With this statement, Dagbladet’s correspondent articulated support for equality and freedom as universal values worth risking one’s life for, values that Scandinavian immigrants had also equated with the essence of American citizenship, and Wermuth’s letter in addition demonstrated awareness that the war directly or indirectly revolved around the issue of slavery.

Though they privately expressed more pragmatic reasons for enlisting, these early Scandinavian volunteers may have been more idealistic in their motivations for war service than was the case for recruits who joined later in the war. According to James McPherson, this was the case for many Anglo-American soldiers, and it was certainly the way Scandinavian Civil War soldiers wanted their service to be remembered.Footnote 10 In several publications, Scandinavian immigrants later described themselves as having volunteered in greater proportion than did any other ethnic group in the United States.Footnote 11 The claim likely has some merit among Norwegian-Americans, who often came to America with less social and economic capital than their Swedish and Danish counterparts and settled in closer-knit rural ethnic enclaves where they likely experienced greater pressure to enlist.Footnote 12 There is, however, also ample evidence of contemporary resistance to military service among Scandinavian-born immigrants. In other words, Norwegian, Swedish, and Danish immigrants entered the military based on a complex set of motivations that was often as much about economic and political opportunity (and social perceptions of honor) as it was about love for the adopted country or anti-slavery sentiment.Footnote 13

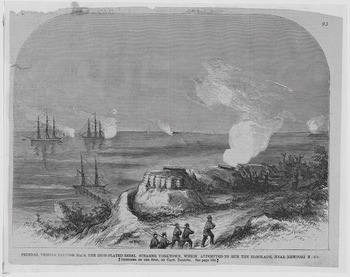

In New York’s Scandinavian company, the early Norwegian, Swedish, and Danish volunteers did indeed publicly claim to be fighting out of idealism, and part of the reason may well have been the fact that the soldiers quickly were exposed to concrete discussions of slavery and abolition. The Union forces at Fortress Monroe were commanded by Benjamin Butler, who since May 23, 1861, had afforded runaway slaves protection within Union lines (see Figure 5.2).Footnote 14

As Eric Foner explains, Butler claimed to be drawing on international law when designating the runaways as “contrabands,” and by May 27, 1861, at least fifty local runaways “including a three-month-old infant” had sought refuge “at what blacks now called the ‘freedom fort.’”Footnote 15 Thus, Scandinavian soldiers stationed around Fortress Monroe experienced first-hand the centrality of slavery to the Civil War, yet the company’s two highest-ranking officers seemingly volunteered for less idealistic reasons than defending “all human beings’ equal entitlement” to freedom.Footnote 16 Captain Balling (see Figure 5.3) admitted in his memoirs that he had no interest in the political questions of the day and also indicated that First Lieutenant Christensen joined the military mainly for economic reasons.Footnote 17 Christensen never wrote concretely about his motivation for enlisting, noting only that “Company I of 1st New York Volunteers was formed in the Scandinavian Society of New York, of which I was then (in the spring of 1861) president.”Footnote 18

Christensen’s brother-in-law, Ferdinand Winslöw, however, in a private account written to his wife Wilhemina in the fall of 1861, suggested that the first lieutenant’s incentive for military service was mainly economic.Footnote 19 “Christensen had to admit of all the debts that bothered him,” wrote Winslöw in October 1861, and Balling years later wrote that Christensen had confided in him: “My house went bankrupt yesterday, I am in dire straits and I do not know what I tomorrow shall give my family to live off of.”Footnote 20

Balling’s reference to Christensen’s “house” probably had to do with the Danish immigrant’s position at a brokerage firm on Wall Street. According to Christensen’s personal papers, he worked for Pepoon, Nazro & Co. on 82 Wall Street until the Civil War’s outbreak in April 1861 but never afterward. Based on Winslöw’s letter to his wife, the company founders, Marshall Pepoon and John Nazro, may have been in financial trouble – or perhaps just been disinclined to help their former employee.Footnote 21 “Papoon [sic] and Nazro promised Christensen to pay Emmy $100 a month during his absence, but cheats and rascals as they are they have never paid the first copper yet.”Footnote 22 Christensen therefore probably enlisted as much for practical reasons as idealism, and the same could be said of his brother-in-law. Though Ferdinand Winslöw also belonged to the group of early volunteers, he made it clear in a letter dated September 22, 1861, that he served as quartermaster of the 9th Iowa Infantry Regiment to avoid being drafted later and having to “go with very bad grace,” thereby alluding to the importance of honor more than patriotic zeal.Footnote 23

As it turned out, the schism between idealism and pragmatism was a recurring theme as Scandinavians in other parts of the United States pondered whether to mobilize for the Civil War. Ivar Alexander Hviid (Weid), who had received Old World military training, organized a recruitment meeting in Chicago on July 29, 1861. Weid’s call in Emigranten was decorated by an eagle holding an “E Pluribus Unum” ribbon, under which the Danish-born immigrant wrote:

Countrymen Scandinavians!

Our adoptive fatherland is threatened by rebels who seek to overthrow the union that now for so many years has brought fortune and blessings to the country. It is every man’s duty to defend the country he resides and makes a living in, and as a result we Scandinavians also have an opportunity to show the new world that we have not yet forgotten the heroism that since olden times has personified the Norseman.Footnote 24

Weid thereby publicly appealed to a common Scandinavian ethnicity and greater American values such as the economic prosperity that Scandinavians associated with the Union and the United States’ ability to create unity out of diversity. Yet, at the individual level, it was clear that Weid did not necessarily fully embrace the creed of “E Pluribus Unum.” When Weid learned that his company would be incorporated into the German-led 82nd Illinois Infantry Regiment, the Danish-born captain felt such urgency to have the decision overturned that he wired the adjutant general of Illinois, Allen C. Fuller, on September 13, 1862, and argued that military and political strife originating from the Old World had been transplanted to the United States: “I think it wrong to order my Company into Hecker. Germans & Scandinavians never agree[.] They are national enemies,” Weid wrote.Footnote 25

Indicating Scandinavian-born immigrants’ limited political leverage, Weid’s complaint changed nothing: the Scandinavian company remained part of the 82nd Illinois Regiment.Footnote 26 Due to their larger share of the population, however, German immigrants had more opportunities to enlist in ethnically uniform units and at times even refused to “offer their Service into a Mixt Regement [sic],” as evidenced by an August 27 letter to Wisconsin’s governor Alexander Randall a few months before the German-led 9th Wisconsin Regiment was mustered into service.Footnote 27 Some German soldiers, as Walter Kamphoefner and Wolfgang Helbich have suggested, were therefore never part of a multiethnic Civil War crucible as “general fraternization across ethnic lines simply did not happen.”Footnote 28 Scandinavian soldiers, on the other hand, had little choice. The majority of Scandinavian soldiers in the Civil War served in ethnically mixed units, and – as the example of Ivar Weid demonstrates – even units at the company or regimental levels were part of brigades and corps that forced Norwegians, Swedes, and Danes to interact with their fellow soldiers and to an extent depend on them for survival.Footnote 29

Yet in Wisconsin a concerted effort was made to raise a large-scale Nordic Civil War unit. As the summer of 1861 turned to fall and winter, community leaders constructed a pan-Scandinavian ethnic identity based on a common martial Viking past while also acknowledging the practical realities of a political spoils system tied to military service and an idealistic belief in – and duty toward defending – American values and the opportunities associated with American citizenship.Footnote 30

On September 2, 1861, Emigranten’s editor Carl Fredrik Solberg reminded his readers that the Scandinavians “owe the country as much as our native-born fellow citizens do” and that since they “in every respect enjoy the same rights” they were obligated to defend the country.Footnote 31 Additionally, Emigranten printed a text by the Norwegian-born community leader and politician John A. Johnson, who had recruited several Scandinavian volunteers around Wisconsin to “help suppress the slaveholders’ insurrection and uphold the country’s constitution and laws.”Footnote 32 In the following weeks, several more letters arguing for Scandinavian volunteerism and idealism appeared in Emigranten and simultaneously revealed the connection between recruitment and politics.

In between the practical appeals to ethnicity and the more high-minded appeals to civic nationalism, Scandinavian leaders recognized the political need to field visible Scandinavian military units in order to have political influence in the future. Solberg later remembered an important exchange to that effect with Hans Heg, likely in the late summer of 1861:

One night after I had gone to bed and fallen asleep Mr. Heg came into my room and got in bed with me and woke me up. He said he had decided to enter the military service and had come to Madison for that purpose. We stayed awake the rest of the night talking over his plans of raising a Scandinavian regiment, concerning which he was very enthusiastic. I remember he said, “The men who conduct this war are going to be the men who will conduct affairs after it is over and if we are going to have any influence then we must get into the war now.” He was shrewd enough to see the trend of things.Footnote 33

Initially, Scandinavian leaders aimed even higher than a regiment. On the evening of September 15, prominent Norwegian-Americans gathered at the Capitol House hotel in the center of Madison with the goal of raising a Scandinavian brigade. Capitol House was by 1861 considered Wisconsin’s finest hotel, with 120 fashionable rooms inspired by East Coast architecture, and the meeting’s setting therefore indicated the Scandinavian elite’s level of ambition.Footnote 34 Hans Heg was appointed the unit’s commanding officer, and in the subsequent weeks the recruitment efforts were stepped up in earnest.Footnote 35 By September 25, leading Norwegians in Madison were so confident in their ability to enlist fellow Scandinavians in purely ethnic units that they wrote to the governor of Wisconsin, Alexander Randall, and informed him that “Scandinavians from different parts of this State” had resolved “to raise a Scandinavian Brigade for the war now pending in this our adopted Country.”Footnote 36

Underscoring the pragmatic aspects of Civil War enlistments, Johnson received a letter from a countryman, Bernhard J. Madson, suggesting a relatively common quid pro quo for helping to raise the desired ethnic units. On September 27, 1861, Madson assured Johnson that he had enlisted two Norwegian men and soon after wrote that he was “hard to work for the Company” and devoting his “entire time” to recruitment.”Footnote 37 Madson had read in Emigranten that John Johnson’s brother, Ole, was “commissioned as recruiting Officer,” and he followed his enlistment update with a specific request: “I wish to know, if I am working for the Company for a position or not, since your brother will without doubt be elected Capt.”Footnote 38 In other words, would Johnson and his brother use their “combined influence” on Madson’s behalf “for a Lieut. post?”Footnote 39 Johnson’s answer, if he ever wrote one, has not been preserved among his personal papers, but Madson, despite his best efforts, never managed to rise above the rank of “sergeant” with the 15th Wisconsin.Footnote 40 Madson’s lobbying did, however, underline the juxtaposition between the idealism of “upholding the country’s constitution” and the practicalities of securing financially attractive leadership positions privately.Footnote 41 In another example, Hans Heg, on Monday, September 30, 1861, issued a call for Civil War service through Emigranten that revealed both the rhetorical idealism of citizenship duties and the political reality underlying ethnic Civil War units: “The authorities that be in this our new homeland have, as we all know, called the citizens of the country to arms to support the government in its attempt to preserve the Union and its constitution,” Heg wrote.Footnote 42

Scandinavians! Let us recognize our present position, our duties and our responsibility as we should understand them. We have still far from carried the part of the war’s burdens in respect to delivering personnel as the Scandinavian population’s great number here in the country oblige for us … While the adopted citizens of other nationalities such as the Germans and Irish have put whole regiments in the field, the Scandinavians of the West have not yet sent a single complete Company of infantry to the grand Army. Must the future ask: Where were the Scandinavians, when we saved the mother country?Footnote 43

The appeal was signed by ten prominent Scandinavian businessmen, editors, and opinion-leaders (in all, nine Norwegians and one Dane) and yielded clues to how the ethnic elite wanted Scandinavian identity to be understood in the public sphere.Footnote 44 On the one hand, Scandinavians were an exclusive group with a common language and culture competing with Germans and Irish immigrants in displays of loyalty (and by extension political power); on the other hand, they were part of a greater national project with values that had by now drawn them to become citizens in an adopted homeland.Footnote 45

As proof that these ethnic Scandinavian military units were exclusive in terms of language, Emigranten’s editor on October 8, 1861, published a letter by Hans Heg, who emphasized that the “Regiment’s officers would be men who speak the Scandinavian languages. Thereby also giving the Scandinavian, who does not yet speak the English language, opportunity to enter into service.”Footnote 46 This reference to a common Scandinavian origin and identity was a practical construction to maximize recruitment – and perhaps also a necessary one, since Yankee-Americans often were not able to tell Danes, Swedes, and Norwegians apart.Footnote 47 Consequently, the exclusive ethnic identity promoted by the Scandinavian regiment’s organizers afforded non-English-speaking immigrants the opportunity to fight in the war, to ensure a monthly income, and to contribute to their adopted country maintaining a certain territorial size and certain political ideals.

Secondly, the call for volunteers introduced a political ethnicity, in which Scandinavian unity, and subtle expectations of future political power, was defined in opposition to the “other nationalities such as the Germans and Irish” that had “put whole regiments in the field.”Footnote 48 Based on the writings of Heg, Solberg, and other ethnic leaders, these exclusive and political perceptions of ethnicity – exclusive ethnicity serving as a foundation for political power – outweighed the more idealistic and universal values also introduced in Heg’s petition.Footnote 49

Still, the rhetoric of universal ideals, calling attention to citizenship’s duties and adherence to foundational American values of equality and liberty, echoed frequently through the pages of Emigranten and the Swedish-American Hemlandet during the Civil War, while less idealistic motivations appeared in private correspondence.Footnote 50

Emigranten’s editor enthusiastically backed the idea of an exclusively Scandinavian military unit and frequently opened up his newspaper to contributions aiding the recruitment effort while personally lauding Hans Heg as “young, forceful and bold, proud, and unwaveringly trustworthy.”Footnote 51 Hundreds of Norwegians, a few Swedes, and approximately fifty Danes eventually accepted the call to enlist in the Scandinavian regiment, but the pace of recruitment also made it clear that a Scandinavian Brigade was far from realistic.Footnote 52 Despite initiating the recruitment process in September, the regiment did not fill its ranks until January 1862.Footnote 53 The 15th Wisconsin was eventually made up of ten alphabetized companies with nicknames such as “St. Olaf’s Rifles,” named after the Norwegian king Olav den Hellige (Olaf the Holy), and “Odin’s Rifles,” which tied Scandinavian-American recruits to a common Viking ancestry.Footnote 54

Similar calls for Scandinavian troops, touting a common ethnicity and defending universal values, with the implicit acknowledgement that there was political gain to be had from ethnic units, were published across the Midwest in the fall of 1861 though on a smaller scale. In Illinois and Minnesota, ethnic leaders who were not affiliated with the recruitment effort in Madison, Wisconsin, simultaneously attempted to organize smaller ethnic companies.

Ivar Weid raised his Scandinavian company from a recruiting station in Chicago; a little further west, around Bishop Hill, Illinois, a Swedish company was organized by Captain Emil Forss, who had been an officer in the Old World, and the unit was named the “Swedish Union Guard.”Footnote 55 On October 2, 1861, Forss announced the company’s existence in Hemlandet and encouraged his countrymen to “join us” in knowing the duty that they owed to “our adopted country” and thereby “renew honor to the noble Scandinavian name.”Footnote 56 Swedish-born Hans Mattson organized yet another ethnic unit around the same themes and also likely with a view to turn Civil War service into a political career.Footnote 57

Mattson succeeded in organizing a Scandinavian company for the 3rd Minnesota Infantry Regiment, but in the end the most ambitious and influential Scandinavian ethnic turned out to be the 15th Wisconsin Regiment commanded by Colonel Hans Heg. In the fall of 1861, Heg asked Claus Clausen, his childhood pastor, to be the regiment’s chaplain. According to Emigranten, Clausen, now forty-one years old, replied that “he regarded it as a calling that it would be his duty to accept, if it could be arranged with his congregations” around St. Ansgar in Iowa.Footnote 58

The Danish-born chaplain’s idealism and sense of duty, in some respects, however, clashed with the more practical and immediate daily concerns of the regiment’s soldiers. Claus Clausen, who was commissioned on December 11, quickly realized that he faced a tall task regarding the “regiment’s moral condition,” where drinking and gambling were regular occurrences.Footnote 59 Underscoring the ethnic tension between Scandinavians and Irish immigrants, an alcohol-induced fight broke out on December 24, 1861, between the 15th and 17th Wisconsin Regiments that left several of the participants with “sore noses and black eyes.”Footnote 60

The challenge Clausen initially faced in connecting with Scandinavian-born soldiers was in some ways surprising given the theological struggle centered on slavery that raged outside Madison’s Camp Randall among Scandinavian clergymen and congregations.Footnote 61 In this conflict, Clausen, who for years had worked outside the official church structure, sided more with the worldly concerns of Scandinavian congregations than with transplanted Norwegian state-church-affiliated clergy and sparked the largest controversy in the Norwegian Synod’s history.Footnote 62

When the Civil War broke out in April of 1861, the Norwegian Synod shut down its educational activities at the German-led Concordia College in Missouri.Footnote 63 Professor Peter Lauritz (Laur.) Larsen, who was responsible for the Norwegian students at the educational institution in St. Louis, issued an “announcement” in Emigranten on May 6, 1861, explaining the decision. “[On] account of the political circumstances the faculty at Concordia College, in addition to the supervising committee, have been compelled to suspend instruction and send the students away,” Professor Larsen wrote and asked that his mail now be sent to Madison.Footnote 64 Larsen’s announcement led Emigranten’s editor to ask a simple, but loaded, question regarding the Norwegian pastors’ position on slavery given the fact that it is “impossible for anyone at all to remain passive” at the current moment.Footnote 65

The question was important, Solberg argued, because rumors were circulating that the Norwegian pastors exhibited pro-Southern sympathies. Solberg expressed hope that the men “to whom our future pastors’ upbringing and instruction is entrusted, is sincerely and unwaveringly devoted to the Union and its government.”Footnote 66 Solberg extended his political arguments with a religious one by stating that “all authority was of God” and that rebellion against the authorities therefore had to be seen as “ungodly.”Footnote 67 Norwegian Synod leaders such as Pastor A. C. Preus immediately sensed the question’s explosive implications and in a private letter dated May 10 warned Professor Larsen, “For God’s sake,” against answering publicly.Footnote 68

Less than a month later, however, John A. Johnson revived the issue of loyalty among the Norwegian pastors when he published another piece on the topic in Emigranten and increased the pressure on Synod leaders. As Johnson revealed in a letter to his brother Ole on June 1, 1861, the newspaper piece and its content was no coincidence:

My leisure time has been occupied for two or three days in writing an article for the Emigranten concerning the union of our church with the Concordia College, St. Louis. I have been urged to do this and I must say also that it was strictly in accordance with my own inclinations. Perhaps you do not know that the faculty of that college are secessionists, Prof. Larson included, I think it is a great shame that the Norwegians should send their youth to such an institution to be educated. I wish to sever our connection with them, and intended to give som[e] pretty sharp blows. How well I have succeeded others must judge. It is pretty hard work for me to write, especially in Norwegian, and I know not how the article will appear in print. The editor seems to be well satisfied with it, though he says is it most too severe in some places. I will send you a copy of the paper as soon as it is printed. I do not wish to be known as the author of the article until I am obliged to, so if anyone asks you, keep dark.Footnote 69

Based on Johnson’s letter, his response was likely solicited by Emigranten’s editor, and it thus provides a peek behind the scenes of the newspaper’s editorial processes as well as its editor’s conscious attempts to shape Scandinavian public opinion in favor of the Republican Party. J. A. Johnson’s letter, signed “X” (but due to a typo published as “H.”), appeared in Emigranten on June 3, 1861, and added fuel to a smoldering conflict.Footnote 70 The rumor that “the faculty at Concordia College was made up of Secessionists or at least men who sympathized with the Secessionists” could only be rebutted by “a denial from one of the Concordia educators themselves,” the correspondent argued.Footnote 71 “Professor Larsen has been asked by Emigranten to explain the issue as a whole and his silence can only be interpreted as a complete confirmation of the rumor’s veracity.”Footnote 72

To defend secession, Johnson continued, the rebels presented two main arguments: “1) that Slavery is not a sin; 2) that resisting the execution of the United States’ legislation in the slave states is not a sin”; the Scandinavian clergy’s position on those two assertions was important for the congregations and the ethnic community to know about, Johnson wrote.Footnote 73

Regarding the first argument, Johnson asserted that for centuries slavery had been considered sinful throughout the civilized world: “England, Denmark, and Holland have through great sacrifice and effort set free the slaves in their possessions,” and in the North not “one in a hundred” would deny that slavery is a “boundless abomination.”Footnote 74

Johnson invoked the founding fathers’ idea that “all men are created equal”; regarding the second argument, the Norwegian-born immigrant noted that all government officials took the oath to uphold the Constitution and that the same was true for immigrants wishing to become American citizens.Footnote 75 Consequently, Johnson argued, the Constitution and the officials elected to uphold it should supersede any authority claimed by local or state governments. Yet defenders of the Constitution in the South “were punished with the most outrageous and painful death.”Footnote 76

The idea that dissenters in the South were in grave danger found expression on several other occasions during the war’s early months and often with a certain narrative hyperbole.Footnote 77 If individual states within the Union were able to undermine the national government’s authority, contrary to the way societies had been organized in the Western world for ages, the consequences could be severe, Johnson warned. “What would the result be, in case a state had the right to secede at its pleasure? If South Carolina has this right then all other states has it and we could soon have 34 governments instead of 1,” Johnson wrote in language indicating threshold principle worries.Footnote 78

It was therefore apparent that the Scandinavian community’s position on such matters, not least the influential clergy’s, had to be clarified. “We have, in good faith, sent our youth down there to be trained as pastors without knowing that we exposed them to influence of the secessionists’ poisonous opinions,” Johnson charged and encouraged the Norwegian Synod leaders to sever their ties to the Missouri Synod and create their own institution of learning.Footnote 79

The week after Johnson’s piece was published in Emigranten a self-proclaimed Scandinavian Democratic voter, Jacob Nielsen of Janesville, Wisconsin, indicating the issue’s importance to the Scandinavian immigrant community, took issue with “H”’s lack of precision regarding the concept of biblical “sin” and thereby foreshadowed a spiritual and political debate that would bedevil the Scandinavian religious community for the rest of the decade.Footnote 80

Johnson’s piece and Nielsen’s reply incited Professor Larsen to make a formal statement in Emigranten on June 17.Footnote 81 Larsen started out by criticizing “a political paper” calling public attention to his political views on the rebellion instead of approaching him privately if it was believed that his position was detrimental to the students he was responsible for educating.Footnote 82 Larsen then proceeded to lay out his position on the two main issues on which everything else depended: “1) Slavery and 2) Rebellion or the relation to the authorities altogether.”Footnote 83

Countering Johnson’s reading of the Bible passage “Do to others as you would have them do to you,” Larsen argued that it was unreasonable for a beggar to expect the prosperous to share wealth in excess of alms and unreasonable for the slave to expect freedom from a master in excess of his “duty and conscience”Footnote 84 – in short, words far from ideals of equality and liberty to Scandinavian readers. Since slavery “existed among the Jews” and therefore was “allowed by God,” Professor Larsen was unwilling to declare slavery sinful. “Of the numerous biblical passages proving that slavery is not a sin, I can just in all haste grasp a few out of many.”Footnote 85 That slavery was not considered a sin by arguably the most prominent Scandinavian clergyman in America turned out to be a key point.Footnote 86

To Emigranten’s anti-slavery editor, Larsen came dangerously close to supporting pro-slavery paternalistic arguments for the institution’s benignity in relations between master and slave, thereby ignoring the injustice and by extension the violence, or threat thereof, underlying the whole system of enslavement.Footnote 87 Emigranten’s opinion, likely voiced by Solberg, disagreed with Professor Larsen on several points and let this be known in the same issue. Describing slavery as the greatest “civic evil” in America, “an absolute enemy of our republican institutions,” the newspaper argued for “inherent human sympathy and the conviction” that slavery was “detrimental both to the slaves and the country,” which left little room to interpret Larsen’s statement as anything other than an expression of Southern sympathy.Footnote 88 It came down to a sense of duty coupled with a sense of common human sympathy for people held in bondage, Solberg argued.

We are driven by an instinctive, spirited patriotism, which awakens in all nations in the moment of danger, the same intense patriotism that manifested itself in Norway during the war of 1814 and in Denmark during the Schleswig-Holstein rebellion of 1848 which was far more than just following from the jurists’ agreement that Norway and Denmark were right.Footnote 89

Here Solberg introduced a key difference between his text and Larsen’s: the emotional and intangibly instinctive aspect of slavery’s relationship to ideals of equality and its key role in the current military mobilization occurring both in both the South and the North to such an extent that the Norwegian Synod could no longer maintain its educational mission in Missouri. Where Larsen attempted to separate the issue of slavery from the recently written ordinances of secession – and to an extent succeeded intellectually in making the case for slavery being biblically sanctioned – the professor failed in this particular public debate unfolding in Wisconsin at a time when Scandinavian leaders were recruiting hundreds of Norwegians, Swedes, and Danes to fight against the slaveholding states, run by landholding planters, in rebellion against American authorities.Footnote 90

In the Norwegian township of Perry, Wisconsin, the local pastor’s position on the issue of slavery seemingly caused considerable tension. According to a later local account, Pastor Peter Marius Brodahl moved with his wife Johanne “into the Blue Valley parsonage in 1857,” but he “endured the hostility of parishioners who disagreed with his stance that holding of slaves was not a sin” during the Civil War.Footnote 91 The account further suggested that Brodahl’s elite Old World education and resulting “self-conscious” behavior set him apart from his parishioners.Footnote 92

The class-based differences between the Norwegian Synod’s leadership and pastors and parishioners not educated in the Old World was also on display after the Norwegian Synod’s annual meeting on June 26, 1861. After the meeting, held in Rock Prairie, Wisconsin, where Claus Clausen preached in the 1850s, the ministers issued a joint statement trying to clarify Larsen’s theological position by stating that it was “in and of itself not sinful to hold slaves.”Footnote 93

The Norwegian Synod’s clergymen, many of whom had been educated at Scandinavian universities and were affiliated with the Norwegian state church, generally rejected the Grundtvigian ideas that inspired Claus Clausen, and in late June 1861 they supported a conservative interpretation of slavery’s sinfulness.Footnote 94 Clausen initially agreed with the joint statement’s wording, as it was required in order to be reinstated in the Synod, and he also signed a document admitting to have sinned by resigning from the Synod in the first place. Yet, when Clausen, in his own recollection, had a little more time to consider the statement, he arrived at the conclusion that “slavery in its essence and nature runs counter to the spirit of Christianity generally and the love of God and humanity [kærlighedsbudet] specifically and therefore had to be a sin.”Footnote 95

In this statement there were echoes of Grundtvig’s Old World position on slavery. If Clausen had read Grundtvig’s parliamentary debate comments made on December 14, 1848, which he conceivably could have, he would have known of Grundtvig’s Old World abolitionism and his position of refuting the right “for one man to possess his fellow men with full right of property; against this I protest in my name, and in the name, I should think, of all friends of humanity.”Footnote 96

Thus, after Clausen accepted the position of military chaplain in late 1861, he became even more closely tied to the regiment organizers’ public anti-slavery position, which may have contributed to him writing a piece for Emigranten called “Tilbagekaldelse” (retraction) on the biblical aspects of the slavery issue, which was published on December 2, 1861.Footnote 97

In words that, to an extent, echoed Grundtvig’s first 1839 statement on Danish slavery, Clausen declared “that one human being holds and uses another human being as his property forcefully under the law and that these human beings’ position called slavery, is declared to be an evil in itself.”Footnote 98 Moreover, Clausen, using a general argument that built on Grundtvig’s 1843 Easter thoughts about a common Christian humanity between Black and white, added that slavery “violates the order of nature and all true Christianity.”Footnote 99 As a result, Clausen was once again thrown out of the Norwegian Synod when he insisted that “slavery was irrefutably sinful.”Footnote 100

Thus, by December 1861, when he published his retraction and joined the Scandinavian Regiment as chaplain, Claus Clausen was offering a religious, and somewhat revivalist, anti-slavery vision more in tune with the Scandinavian congregations where many parishioners had acquaintances, friends, or family members serving in the military to suppress the rebellion.Footnote 101

In time this disagreement over slavery’s sinfulness, instigated by anti-slavery Norwegian-born leaders, contributed to a split within the Scandinavian-American church and revealed important fault lines between the Scandinavian-American clergy tied to the Old World state churches and pastors, like Claus Clausen, who were critical of state church positions. Additionally, there was a class component tied to the debate as well. To the university-educated synod leaders, the discussion about slavery’s sinfulness was primarily intellectual and secondarily political.Footnote 102

To community leaders such as Clausen, Solberg, and Heg, who had lived in small pioneer settlements among the Norwegian Synod’s laity (and seen rural hardship up close), it was clear that the issue of slavery’s sinfulness was political first and intellectual second. The issue of slavery and the Republican Party’s deepening fight for emancipation also raised important questions about race relations within American borders as 1861 turned to 1862, and the connection became increasingly clear to the Scandinavian-born men as they went into the field with their respective military units.

Yet, despite the synod conflict’s rhetorical and practical ferocity and Clausen’s anti-slavery position, it was evident as the war progressed that many of the 15th Wisconsin’s leadership were more concerned with liberty and equality as it pertained to opportunities for upward social mobility among Scandinavians than they were with ensuring freedpeople an equal place in an American free labor economy.

***

On a cold, rainy Sunday evening, March 1, 1862, the Scandinavian Ladies of Chicago presented Colonel Hans Heg of the 15th Wisconsin Regiment with a beautiful blue and gold silk banner (see Figure 5.4). “For Gud og Vort Land!” read the flag’s inscription (For God and Our Country), an adaptation of the well-known Old World Scandinavian rallying cry “For Gud, Konge og Fædreland” – “For God, King, and Fatherland.”Footnote 103 The inscription said much about the Scandinavian ethnic elite’s public perceptions of Civil War service, as the importance of religion and adherence to “Our Country,” a nation where citizenship – theoretically – was based on universal ideas about equality, were recognized by the flag-makers.Footnote 104 Additionally, even as it drew inspiration from Scandinavia, the flag also demarcated the Old and the New Worlds, monarchies and republican government, by erasing the word “King” from the Scandinavian-American battle flag.Footnote 105

Figure 5.4 The Scandinavian Regiment’s battle flag with the inscription “For Gud og Vort Land” (For God and Our Country).

Yet the Scandinavian regiment was, in part, created because of Scandinavian immigrant leaders’ fear that Norwegians, Swedes, and Danes, despite the privilege afforded them due to their white skin and Protestant religion, were somewhat marginalized in relation to the American political and economic establishment, because of language barriers, lack of capital, and lack of access to a political spoils system. For example, the problem of getting Scandinavian-American officers appointed by Wisconsin’s governor was described by Colonel Heg in a letter to J. A. Johnson in August 1862: “I have no particular pride of nationality in the matter, but I know we have men amongst the Norwegians, capable of being developed – and of becoming good military officers – when modesty prevents them from gaining any position.”Footnote 106

Yet modesty did not prevent Bernt J. Madson from receiving his coveted lieutenant position; rather, it was likely the inability of the Scandinavian ethnic elite to expand the pool of available officer slots outside the 15th Wisconsin, which by 1861 was the only regiment where a Scandinavian immigrant with no military experience could realistically hope to be appointed.

As we have seen, Madson wrote J. A. Johnson in early October 1861 petitioning him to throw his and his brother Ole C. Johnson’s weight behind a lieutenant appointment; even by late 1862 he was still lobbying for a better position.Footnote 107 Writing from camp near Nashville, Tennesee, Madson implored J. A. Johnsn to do him a favor by “seeing Gov. Solomon for me” to ask “if he could give me a Lt post in one of the new Reg’ts, Hoping you will do all you can in [sic] behalf.”Footnote 108 No officer position outside, or even inside, the Scandinavian regiment materialized for Madson, however, and the same was true for the vast majority of Norwegian immigrants, by far the most important voter demographic within the Scandinavian community in Wisconsin.Footnote 109 As Olof N. Nelson admitted in his otherwise hagiographic account of the Scandinavian imprint of America, “there were, undoubtedly, Scandinavians in all the fifty-three Wisconsin regiments. But while the Norwegians supplied a large number of common soldiers, they do not appear to have distinguished themselves as officers.”Footnote 110

The Scandinavian immigrants who did receive an officer’s appointment generally did so because they had been part of Scandinavian ethnic units originally or because they had Old World military experience, which was badly needed in the United States in 1861 and early 1862.

The civic nationalism publicly expressed by Scandinavian leaders in their initial calls for ethnic Civil War units was, however, mirrored and reinforced in the songs the soldiers wrote when they did take the field in 1861 and 1862.Footnote 111 Swedish-born Nels Knutson, for example, on a cold and dreary night on picket guard in Missouri, conjured up a song about brotherhood, common humanity, courage, freedom, and religion. “Now brothers and comrades,” the song began, the time has come to fight for what is right and the cause of humanity in “God’s honor.”Footnote 112 To achieve this end, Knutson, admitted, hard battles would need to be fought – he invoked help from “the God of War” – but in the “land of the brave and the home of the free,” that was the price to pay “for honor, duty, and country.”Footnote 113

By 1862, Scandinavian immigrants’ understanding of “God and Our Country” had important implications in relation to who they perceived as being worthy of inclusion.Footnote 114 As such, the regimental flag, the public recruitment appeals, and the popular culture emanating from Scandinavian Civil War service all reinforced a sense of nationalism based on freedom expressed through commitment to a civic nationalism and often also Protestant religion. The motivations privately expressed, however, revolved around economic and political gain. Old World Scandinavian religion, Protestant and Lutheran as opposed to Irish or German Catholic, played a part in everyday demarcations of “us and them,” and, despite anti-slavery rhetoric in the public sphere, everyday practices revealed less than full support for racial equality.

While Grundtvig preached the importance of viewing “all of mankind” as “children of one blood” and army chaplain Claus Clausen called the Norwegian Synod’s statement on religiously sanctioned slavery “a web of sophistery,” it was clear that Old World ideas of racial superiority, coupled with the allure of land acquisition at the expense of Native people, often influenced Scandinavian-born people’s worldview both at the political and the grassroots community levels.Footnote 115

The second session of the 37th United States Congress convened on Monday, December 2, 1861, the same day that Scandinavian readers out west opened Emigranten to Claus Clausen’s retraction and an editorial focused on the state of the Union. On December 3, Lincoln’s private secretary John George Nicolay “communicated” the president’s first annual message to Congress and distributed the content widely.Footnote 1

The president’s message, as we have seen, underscored the threshold principle’s importance in terms of population growth (“eight times as great” since the 1790 census) and acquisition of territory to “furnish homes for white men” by colonization of “colored men.”Footnote 2 Lincoln’s words immediately spurred a flurry of activity in Danish and American diplomatic circles and demonstrated the racial ideology of white superiority that connected colonization abroad and colonialism at home, rhetorically as well as chronologically and practically. Immediately after Lincoln’s message, the Danish charge d’affaires in Washington, DC, Waldemar Raaslöff, alerted the government in Copenhagen (see Figure 6.1). In a December 6 report to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Raaslöff directed the ministry’s attention to Lincoln’s “latest message” and “the planned Colonization of Negroes” who were, or would be, “emancipated due to the progress of the military operations.”Footnote 3 In Lincoln’s message, Raaslöff saw opportunities to revive previous discussions over colonization between the United States and Denmark.

Concerns over labor shortages on St. Croix, St. Thomas, and St. John had been a recurring theme since emancipation in 1848. As freedmen and women exercised their newfound, albeit limited, autonomy to seek employment opportunities away from agricultural labor, their former masters and Danish colonial administrators grew increasingly worried. In one estimate, the number of agricultural workers “decreased by one quarter” within the first five years of emancipation, and the lack of laborers in turn created economic challenges that played a role in a brief Danish parliamentary discussion of selling the West Indian “possessions” in 1852.Footnote 4 Partly due to worries related to the threshold principle, Danish politicians voted against selling St. Thomas, St. Croix, and St. John and instead worked consciously to bolster the economic interests of the islands’ elites by exploring opportunities for importing foreign labor.Footnote 5 The story was not singular to the Danish West Indies. Ever since the downfall of slavery in the Caribbean, European colonial powers had been seeking new sources of labor to remedy shortages across the area.Footnote 6 By the 1840s, Caribbean colonies, not least the British West Indies, were receiving “coolies,” Asian laborers who worked for such low rates that many observers felt these laborers, themselves only partially free, were also undercutting the costs of slave labor.Footnote 7 From 1856 and forward, the St. Croix Burgher Council, a citizens body consisting of elected representatives from the island’s international elite, spearheaded an effort to bring in laborers from areas as geographically diverse as “Madeira, Africa, China, and the East Indies.”Footnote 8 But because the distance to the United States was much shorter and the cost of importing African American laborers therefore much cheaper, the Danish government and the St. Croix Burgher Council started viewing Black laborers in the American South as a more advantageous and economically favorable way to alleviate labor shortages.Footnote 9

Concerned with profit and with an eye toward international exchange markets, St. Croix planters and government officials by 1860 followed American news with particular interest and turned their gaze toward the large slaveholding nation to the north when the United States navy increased its anti-slaving patrols. In the spring of 1860, American naval efforts “near the Cuban coast” resulted in the seizure of three vessels, “the Wildfire (26 April), the William (9 May), and the Bogota (23 May),” with nearly 2,000 enslaved Africans aboard.Footnote 10 The “US Home Squadron” transported the ships to Key West in Florida, and the news of this potential labor source spread among the St. Croix planter class in June.Footnote 11 By the end of the month, St. Croix governor Vilhelm Birch encouraged the American consul on the island, Robert Finlay, to inquire if the American government, instead of sending “savages” to West Africa, could send 500 to 1,000 of the so-called recaptives to St. Croix, where they would be set to labor for five-year terms.Footnote 12

Finlay responded positively to Birch’s question and forwarded the correspondence to the American secretary of state, Lewis Cass.Footnote 13 Underscoring the situation’s importance, Denmark’s King Frederik VII in July personally signed a document dispatching chamberlain Louis Rothe to conduct negotiations with the American government as it debated the recaptives’ fate.Footnote 14 Rothe soon proposed transferring up to 2,000 Africans to the Danish West Indies as it, in his estimation, would save the Americans the expense of a return journey, help planters on St. Croix acquire cheap labor, and provide “the African race” civilizational uplift through “the advantages” the island of St. Croix offered.Footnote 15

In the end, however, President James Buchanan’s administration chose to send the recaptives to Liberia and effectively brushed off Danish diplomatic advances with the explanation that “the laws of the United States provide a positive mode of disposal for the slave cargo of all vessels captured in the procuration of the African slave trade.”Footnote 16 Absent from Buchanan’s argument were considerations of the human cost. By late summer, the American government had sent 1,432 recaptives from Key West, but only 823 made it to Liberia, as many other perished from disease.Footnote 17 Danish officials’ correspondence also demonstrated that economic interests and perceived racial hierarchies, more than concerns over civilizational uplift, determined their policy proposals. As Rothe wrote on September 14, 1860, the “imperfectly civilized population” of Liberia was unfit to continue receiving boatloads of “captured Africans” in need of being “reclaimed from barbarism” on its shores.Footnote 18

Before returning home, Rothe offered his American counterparts an open invitation to reconsider the colonization offer in the future and left instructions to his successor.Footnote 19 Thus, Waldemar Raaslöff in December 1861 took it upon himself to again present Caribbean colonization plans when Abraham Lincoln brought up the issue to Congress.

In a meeting with Secretary Seward on December 14, Raaslöff posed the question of “transferring Negroes found on seized slavers” and attempted to gauge the American government’s willingness to support larger colonization plans.Footnote 20 “Since the number of Negroes” who were or would be emancipated already added up “to several thousand” and was “steadily rising,” Raaslöff argued, it would “be impossible for the United States to provide work for them all.”Footnote 21 In short, they would soon “be a big burden.”Footnote 22

Raaslöff had visited Fort Monroe in the summer of 1861 and was therefore likely familiar with runaways being considered contraband.Footnote 23 Moreover, the Union navy’s capture of South Carolina’s Port Royal and the surrounding Sea Islands in November 1861 made white residents leave while approximately 10,000 formerly enslaved stayed behind.Footnote 24 Raaslöff stressed that these so-called contrabands were an important part of an ideal colonization agreement:Footnote 25

The negroes emancipated because of the war, particularly in South Carolina, are among the best and most civilized in the United States and thereby are much above the negroes found on slaveships, as these are completely raw and uncivilized, [and] do not know the language, the work and the entire way of living here and in our colonies.Footnote 26

Seward, in Raaslöff’s words, viewed the Caribbean colonization idea favorably and explicitly encouraged the Danish authorities to appoint agents, equip ships, and solicit the labor of “negroes emancipated because of war” along the eastern seaboard.Footnote 27 Seward also offered the American government’s assistance, a proposal that aligned poorly with the later recollection of his opposition to colonization (always in support of “bringing men and States into the Union” and never “taking any out”), but it aligned well with the Lincoln administration’s commitment to a white man’s republic in the early years of the Civil War.Footnote 28

Colonization would remove Black people to make room for white people, and, if Danish authorities enticed a few thousand fugitive slaves settle in the West Indies, such an arrangement could potentially open the door to much larger agreements with powerful Caribbean colonial powers such as Britain, France, or Holland.Footnote 29 Consequently, Seward supported the idea.Footnote 30

The Secretary of State answered me that this idea was actually completely new to him, as he had not thought of placing the above-mentioned emancipated slaves this way, but that he, without having presented it to the President, pronounced himself for the plan and assured me that its implementation would in the best way be supported by the United States government.Footnote 31

According to Raaslöff’s description of the December 14 meeting, Seward reiterated the importance of “completely voluntary” emigration to St. Croix but also believed that many runaway slaves would willingly work in the Caribbean and “noted that any foreign government that would try and induce free negroes to emigrate to their West Indian colonies would find the United States government ready to render all possible assistance.”Footnote 32

As a result, Danish officials for months worked hard to realize a plan that would facilitate colonization of the “most civilized” emancipated Black laborers.Footnote 33 Encouraged by Raaslöff, the governor of St. Croix Peter Birch and the island’s Burgher Council quickly formulated a proposal.Footnote 34 Governor Birch shared Raaslöff’s perspective on runaway “negro slaves,” whom he described as a burden on the United States, and confidently wrote to Copenhagen on January 2, 1862, that the American government was considering “disposing” of “these, under present conditions, inconvenient individuals by colonizing them in Central America or the West Indies.”Footnote 35

Following a meeting on January 6, 1862, the council, according to Birch, “declared themselves willing to receive emancipated negro slaves” to the number of 300 to 500.Footnote 36 Additionally, Birch added in his letter to Raaslöff, the St. Croix planters were willing to pay the costs of the transportation, as long as they received agricultural workers who would contract to work for at least three years in sugar cultivation on the island in exchange for free housing, a ration of flour and salted fish, and pay of 95 cents per week with twenty-four work days per month.Footnote 37 In a flurry of letters aimed at the top of Lincoln’s administration, Raaslöff offered free transport to St. Croix for people of “African Extraction,” a work day from sun up to sun down, and, echoing Lincoln’s annual message, all in an “extremely agreeable and salubrious” climate.Footnote 38

Yet by the spring of 1862 it seemed increasingly clear that the formerly enslaved had little interest in taking advantage of the Danish proposal. African-American perspectives on colonization could be gleaned from the agent appointed to hire laborers by the St. Croix Citizen’s Council on February 4, 1862.Footnote 39 The agent, George Walker, quickly ran into problems recruiting “refugees from the Southern States” and discussed the nature of his difficulties along the South Carolina Sea Islands in a letter to the St. Croix Governor’s Mansion:Footnote 40 “It is more than probably that I can get the consent of Mr. Seward to go to Fort Monroe, Hatteras, or Port Royal, and hire all the negroes I can get, who will go willingly to St. Croix, as laborers,” Walker wrote to Governor Birch on March 16, 1862, “but when I go to the negroes themselves to induce them to go aboard ship and go over the sea, I am afraid all the satisfaction I shall get will be ‘no want to go Massa.’”Footnote 41

Walker added:

The negroes are strongly attached to the soil where they live, and their masters tell them that the “Yankees” are making war for the purpose of catching them and selling them off to Cuba, and I fear that field hands, which are the only class you want, will have a great aversion to going on board ship, and the Government will not probably now use any coercion to induce them to go.Footnote 42

Walker seemingly held out hope that the American government could use some form of “coercion” in the future to induce so-called contrabands to leave the country but realized it was almost impossible to attract former slaves, who would “go willingly,” because of the comparatively poor labor conditions on the islands.Footnote 43 Former slaves hired by the American government in coastal Carolina made $8.00 a month, according to Walker, which was considerably more than the maximum 15 cents a day on weekdays and 20 cents on Saturdays (even when factoring in the plantation laborers’ accommodations and garden plots), proposed by the Danish authorities.Footnote 44

Additionally, given Lincoln, Seward, and several other high-ranking Republican supporters’ insistence that colonization had to be voluntary, agents like Walker faced an uphill challenge since the African-American community was far from silent on the issue.Footnote 45 Despite some internal division regarding the judiciousness of colonization, Black Americans and abolitionists had resisted colonization attempts for decades.Footnote 46 On January 23, 1862, a little more than a month after Lincoln’s annual message to Congress, freeborn abolitionist and lawyer John S. Rock pointed out the racial discrimination behind the Republican Party’s course on colonization and immigration at the Annual Meeting of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society. In his speech, Rock argued that sending Black Americans out of the country instead of utilizing their abilities at home, for example in armed service, undermined the nation’s military strength and highlighted the racial discrimination underlying the Republican Party’s homestead advocacy. “Why is it that the people from all other countries are invited to come here, and we are asked to go away?” Rock asked. “Is it to make room for the refuse population of Europe?”Footnote 47

Given the opposition to colonization among the Black population and the sensitivity with which the issue was treated by the Lincoln administration, Raaslöff by late spring suggested an alternative to Seward.Footnote 48 In a May 26, 1862, letter, Raaslöff reiterated his preference for former slaves with agricultural experience but was prepared “to negotiate and to conclude a special convention for the transfer to that island of Africans who may hereafter be found on board of slavers captured by cruisers of the United States.”Footnote 49

While these “captured Africans,” from a Danish diplomat’s perspective, were far from equal to white men, he reiterated the government line that the opportunity to live with an “excellent and highly civilized colored population” could however expedite the development of these supposedly primitive workers.Footnote 50 In the Danish diplomat’s mind, and in actual labor practices on St. Croix, a hierarchy of workers clearly existed. As Raaslöff informed Seward, former slaves on St. Croix were divided into first-, second-, and third-class laborers and paid accordingly based on an assessment of their knowledge, ability, physical strength, and endurance.

The captured African, who generally is almost a savage, entirely unaccustomed to and unacquainted with regular agricultural labor, would therefore quite naturally and justly have to pass through the lower classes and not become entitled to form part of the first class, which involves the highest pay.Footnote 51

Former slaves with agricultural experience, presumably elevated in their social standing through interaction with Europeans, were at the top of such a hierarchy, which explained Raaslöff’s interest in South Carolina; but, realizing the short-term diplomatic and legal obstacles for such an agreement, and perhaps more importantly Black opposition to voluntary colonization, the Danish diplomat settled for what he considered third-class laborers.

Raaslöff’s arguments were repeated almost word for word in newspapers such as the National Intelligencer after June 10, 1862, when the Government Printing Office officially disseminated the correspondence between Seward and Raaslöff.Footnote 52 On June 13, the National Intelligencer, based on the Newark Daily Advertiser, described the “New Plan of Negro Colonization,” where Raaslöff’s portrayal of Africans as almost savages was slightly rephrased and the Danish diplomat’s position that the endeavor would be “entirely satisfactory” from a “humane and christian” perspective was relayed.Footnote 53 Moreover, in a newspaper clipping enclosed by Raaslöff in his report home on July 15, 1862, the National Intelligencer lauded the Danish government for its philanthropy in regard to “recaptured Africans” and hoped the Danish proposition “would receive the sanction of Congress” as it offered the “triple advantage” of “a benefit to the productive industry of a friendly Power, a benefit to the poor negroes themselves, and a saving of great expense and inconvenience to us.”Footnote 54

Demonstrating the chronological connection between issues of colonization and colonialism, Raaslöff’s May 26 offers to “conclude a special convention” on “captured Africans” coincided with Scandinavian editors out west, in an echo of Republican Senator Benjamin Wade, excitedly announcing that “Land for the Landless” had triumphed over “Negroes for the Negroless” as the long-awaited Homestead Act was finally signed.Footnote 55

Critical perspectives on homestead legislation were absent from Scandinavian newspapers, but abolitionists connected colonization and colonialism and criticized the political establishment’s land distribution in favor of white Europeans, a plan that, in their view, further enabled the enslavement of “Africans in the Americas.”Footnote 56

The Danish government’s active work to amend American colonization policy and Scandinavian-American immigrants’ support for Indian removal indicated an acceptance of Old World racial ideology that, in part, shaped life and policy debates within American borders.Footnote 57 Danish diplomats like Birch, Rothe, and Raaslöff characterized Africans as “savages” and “barbarians”; only enslaved people who lived among white planters, such as those in South Carolina or the West Indies, were described as having civilized potential and in the American West, Norwegian, Swedish, and Danish immigrants’ descriptions of Native people often echoed those of Old World colonial representatives. Designating American Indians as “wild” and “savages” helped settlers justify their pursuit of land.Footnote 58 As such, Scandinavian immigrants, as demonstrated by Karen V. Hansen, aided “the US imperial project of seizing and transforming North America,” even if they did not arrive as “conscious participants in a colonial scheme.”Footnote 59 Yet a key policy plank in this “colonial scheme” was the Homestead Act, which for years had found explicit support among the Scandinavian elite and rural communities. The Homestead Act was an important part of their support for the Republican Party, as well as being an important part of their divergence with the abolitionist movement.Footnote 60

To Emigranten the Homestead Act also had important transnational implications, as it was clear that it would “benefit the settlers by promoting the nation’s development.”Footnote 61 In part due to the Lincoln administration’s conscious efforts, the Homestead Act attracted widespread attention in Europe, not least in Scandinavia, and thereby advanced Republican politicians’ combined attempts to grow both territory and population in accordance with the threshold principle.

When Abraham Lincoln spoke in December 1861 of “furnishing homes for white men” through acquisition of territory and colonization of “colored men,” he was simultaneously laying the ideological and practical groundwork for further expansion into the west.Footnote 62 The Homestead Act’s passage in May 1862 (along with the Morrill Land-Grant College Act and the Pacific Railroad Act in early July) further cemented the Lincoln administration’s commitment to white settlement on land previously occupied by Native people.Footnote 63

To Emigranten the Homestead Act’s “benefit to settlers without means” was “too evident to warrant any explanation,” and its importance underlined by the fact that it was translated word for word (just as an earlier homestead proposal had been as far back as 1854).Footnote 64 Similarly, Hemlandet praised it a victory for free labor as the landless could now become free men.Footnote 65 The Homestead Act, which allowed citizens to claim seemingly free land if they were willing to inhabit the area and improve the land for five years, thereby fulfilled a long-standing Scandinavian immigrant dream as well as a long-standing Republican goal.Footnote 66

Scandinavian-American immigrants quickly seized on the opportunities provided by the Lincoln administration, but tellingly there was no mention of the Dakota people living in Minnesota – or indigenous people living elsewhere – when the Homestead Act’s potential was espoused in Midwestern immigrant enclaves. On August 6, 1862, Hemlandet published a letter from Andrew Jackson, a Swedish-American pastor living in Minnesota, which drew Scandinavian immigrants’ attention to homestead opportunities:

It is known that the Swedes and Norwegians have taken up a section of approximately 15 square miles that is very sparsely settled. I had hoped that our countrymen would come and settle among us to fill the empty space, especially as the Homestead Act makes it so easy to acquire land here.Footnote 67

Time was of the essence, however. According to Jackson, who first arrived at Green Lake in 1859, Americans were eyeing the land, and so the Swedish pastor’s countrymen needed to be both faster and bolder if they were to get a slice of “empty” Minnesota farmland before the Americans did.Footnote 68 Otherwise Scandinavian newcomers would have to settle even further west where there would be no pastors, no schools, and no fellow Scandinavians: in short, immigrant sheep without a herder. Hurry to Minnesota, Jackson pleaded.Footnote 69

Pastor Jackson’s 1862 letter fit a broader pattern among Nordic settlers. As we have seen, since the first Scandinavian newspaper broadside was published in the Midwest in 1847, editors and correspondents in immigrant enclaves had regularly expressed support for territorial expansion as well as general disregard for Native people’s interests and rights.Footnote 70 In a letter dated November 16, 1857, Norwegian-born pastor Johan Storm Munch wrote to his brother in Norway about Minnesota extending westward “to the possessions of the Indians” and noted that the Norwegians had “occupied the best land” while only briefly alluding to American Indians’ presence in travel descriptions.Footnote 71 “Here and there (although now seldom) a forlorn Indian, wrapped in his blanket, curiously stares,” Munch wrote in an account of a journey down the Mississippi, which included observations from a trip inland:Footnote 72

The road went over desolate, wild prairies, and from there into thick, dark woods, where only a couple of years ago hordes of Indians had their home. Now, however, hardly one was to be seen.Footnote 73

Pastor Munch’s wife, Caja, in a letter home relayed the idea that “here in America all were equal,” yet her impressions of Native people in a letter to her parents dated October 24, 1858, made it clear that she did not consider them so.Footnote 74 Caja Munch described “Indians” as “howling like wild animals,” travelling in big bands, instilling fear in Scandinavian women, and, in an anecdote about alcohol, lacking self-control.Footnote 75

While Scandinavian-born men and women on several occasions also expressed some empathy for Native people, it was often with the assumption of inevitable Indian dispossession.Footnote 76 Thus, even Scandinavian immigrants who “wrote of shameful treatment of Indians” did not, as Betty Bergland points out, challenge “the justice of federal policies ceding land.”Footnote 77 This justification of land-taking was rooted in a notion of white superiority: civilized Europeans as opposed to “half-wild children of nature.”Footnote 78 In this sense, the Scandinavian immigrants’ whiteness (and their Protestant religion) set them apart in their own eyes from American Indians and people of African heritage. In Jon Gjerde’s words:

As they began to label themselves in relation to others, European immigrants transposed the despotism of Europe to the unfreedom of the nonwhite as a vehicle to juxtapose their freedom in the United States. As historians have illustrated time and time again, this transformation from the unfree European to the free American tragically was connected to the denial of freedom to others.Footnote 79

Often Scandinavian immigrants did not reflect on the fact that they were settling on land formerly inhabited by American Indian tribes, though they were clearly aware of the fact. Norwegian-born Ole Andersen, for example, hoped to attract fellow immigrants to the newly organized Dakota territory in 1861 by detailing how settlers were benefiting from native people’s agricultural practices. “In the James Valley and along the Missouri wheat yields are 26 bushels an acre. Corn, grown on old Indian plantings, yields 78 bushel an acre,” Andersen wrote.Footnote 80

Also C. C. Nelson, who settled in Minnesota and recounted his experiences later in life, noted the presence of indigenous people. “We arrived on the 10th day of July, 1858, and found the country a complete wilderness, with the exception of Indians who were there only human beings around here,” Nelson wrote, before adding, “We didn’t find them very pleasant or agreeable.”Footnote 81

Moreover, Pastor Jackson’s letter from August 6, 1862, described the area around Green Lake, Minnesota, as “empty space,” despite the fact that it was located on recently ceded Native lands and located only about 30 miles east of the Yellow Medicine Agency where Dakota people retained an ever-decreasing slice of land west of the Minnesota River.Footnote 82

Though the Homestead Act gave the impression that the “unappropriated public lands” offered were indeed uninhabited land, the situation in Minnesota proved more complex.Footnote 83 Despite negotiations throughout the 1850s with the Dakotas, which led to Indian bands ceding “millions of acres,” including ancestral grounds, the American government’s failure to survey reservation borders until 1858 strained the relationship between Native Americans and Northern European settlers.Footnote 84

Tension between Dakota bands and immigrants had been on the rise at least since late 1854 when German-born settlers moved into “abandoned summer lodges” built by Sisseton bands.Footnote 85 As described by Gary Anderson, European immigrants thereby effectively reduced the land available for hunting, and, when Dakota bands returned in the spring of 1855, newly arrived settlers were confronted by Indian women angrily pounding their fists into the ground, signifying possession of the land.Footnote 86 As more German and Scandinavian settlers moved into the river valleys, lack of cultural understanding caused ever-simmering conflict.

Most of these settlers were foreigners who knew nothing about the Indians and did not understand the importance of reciprocity in Sioux society. If they aided a passing hunting party, it was usually out of fear rather than from a willingness to share. Consequently many Dakota men came to hate their German and Scandinavian neighbors.Footnote 87

Additionally, the Dakota community, split between farmers and hunters, disagreed on how to deal with settlers. Spurred by government agents, who handed out “annuity money and food only to Indians who showed some inclination to become farmers,” a faction of Dakota tried to adopt white people’s practices and appearances, but the hunter bands continued to view white people as trespassers.Footnote 88 The settlers, however, remained in place and – bolstered by a series of treaties signed between 1837 and 1858 – over time only augmented their presence.Footnote 89

According to the 1850 census, 6,038 white people (and thirty-nine “free colored”) lived in the Minnesota territory, whereas 8,000 “Sioux” were counted.Footnote 90 By 1860, however, Native people made up just 1.4 percent of Minnesota’s population (2,369 out of 172,023), while foreign-born residents accounted for 34.1 percent (58,728) with 6.84 percent of the recently admitted state’s population registered as Scandinavians (mainly Norwegians and Swedes).Footnote 91

Thus, in the spring of 1861, when a conflict over stolen pigs from a nearby farm was on the verge of escalating to violence, the Dakota made clear that both land and animals belonged to them and that Scandinavian immigrants, in turn, belonged east of Fort Snelling. Still, settlers kept coming.Footnote 92

By the summer of 1862, the US government’s failure to deliver promised food supplies and money, along with the immigrants’ encroachment, had stretched Dakota hunters’ trust to the breaking point.Footnote 93 Out of desperation, a band of Dakota raided a warehouse in early August, which allegedly prompted one “Indian agent” to exclaim, “If they are hungry, let them eat grass.”Footnote 94 On August 17, four Dakota hunters, in a tragic attempt to demonstrate bravery, attacked and killed five settlers in Acton, Minnesota, and in the early morning of August 18 asked the support of Little Crow, the most influential leader of the Mdewakanton band.Footnote 95 As Gary Anderson and Alan Woolworth have explained, several of the Dakota hunters who sought out Little Crow were part of an influential hunting lodge that had “increasingly become an instrument for resisting government acculturation and a forum for voicing discontent with the reservation system.”Footnote 96 The hunting lodge denied admittance to Indians who, in accordance with the American government’s wishes, had taken up farming, and the hunters’ position was strengthened by the delay of provisions and annuities. Thus, “faced with the full force of about a hundred members of the soldiers’ lodge, Little Crow reluctantly agreed to join the war.”Footnote 97

Shortly thereafter, at 7 a.m., the attack, supported by the majority of Dakota men, began in response to broken treaties, hunger, and foreign-born advances onto what they considered their lands.Footnote 98 Scandinavian immigrants in the area where Pastor Jackson had advocated future settlements were among the first attacked. Soon letters recounting the trauma of violence started appearing in Scandinavian-American newspapers and reinforced widespread disdain for the Dakota Indians’ humanity and their claims to land.

On August 27, 1862, two lengthy articles appeared in Hemlandet under a large typeset heading “Fiendtligt anfall af Indianerne i Minnesota” (Hostile attack by Indians in Minnesota) followed by the subheader that in translation read “Horrible bloodbath among the settlers on the borders.” A correspondent, who was only identified as “A Minnesotan,” described a community that within a month had gone from blissful ignorance of the Civil War to feeling the conflict’s consequences in a shockingly concrete manner:

We did not think we were in any danger or that we should have any need for our soldiers here at home, but we were deceived. The Indians, both the Sioux and the Chippewa, have just now attacked our settlements on the border and are raging forward like wild animals, burning, stealing, and murdering anything in their path.Footnote 99

The Dakota initially targeted settlements along the southern part of the state: New Ulm, Mankato, Fort Ridgeley, and, a little further to the north, Norway Lake. In Wisconsin, Emigranten in a September 1 article under the headline “Indian Unrest in Minnesota – a Norwegian-Swedish Settlement Attacked” brought the war’s horrors into Scandinavian log cabins:Footnote 100

The Norway Lake settlement is chiefly made up of Norwegian and Swedes. They were gathered in church Wednesday afternoon on August 20 and on the way back from service they were attacked by a roaming mob of Indians. Some rode ponies, other[s] were on foot and approximately fourteen people were killed and horribly mutilated … There is now no communication between Green Lake and Norway Lake.Footnote 101

The reports published in Hemlandet were equally grim. “A number of countrymen killed,” read a headline on September 3, 1862, where a letter from Red Wing, Minnesota, named some of the war’s casualties: “Lars Lindberg, Anders Lindberg, August Lindberg, A. B. Brobäck and their child Daniel Brobäck” among several others.Footnote 102 Andrew Jackson, who had advocated land claims in Minnesota three weeks earlier, doubted his survival when he penned a letter on August 25. “[The Indians] are on horseback and seem to be well trained in their hellish doings,” Jackson wrote. “God help us.”Footnote 103

The assaults on civilians and ensuing military engagements were harrowing for all involved. Pastor Jackson, perhaps too traumatized to describe the violence, wrote to fellow pastor Erik Norelius on August 20, 1862, in the middle of the attacks, but did not devote a single word to his experience or those of congregations by Eagle Lake, Nest Lake, Wilson Prairie, or Norway Lake. Similarly, Swedish-born Erik Jönsson could apparently never bring himself to send a letter, written on March 3, 1863, to his Old World family detailing the trauma.Footnote 104