Amitriptyline is one of the first ‘reference’ tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs). Over the past 40 years a number of newer tricyclics, heterocyclics and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been introduced (Reference Garattini, Barbui and SaracenoGarattini et al, 1998). Despite several large systematic reviews comparing tricyclics and SSRIs there is no clear agreement over first-line treatment of depression (Reference Song, Freemantle and SheldonSong et al, 1993; Reference Anderson and TomensonAnderson & Tomenson, 1995; Reference Montgomery and KasperMontgomery & Kasper, 1995; Reference Hotopf, Lewis and NormandHotopf et al, 1996; Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment, 1997a ). Grouped as a whole, tricyclics appear to have similar efficacy to SSRIs, but are slightly less well tolerated. If tolerability is measured according to the numbers of drop-outs occurring in randomised controlled trials (RCTs), the number needed to treat (NNT) with SSRIs to prevent one tricyclic-related drop-out is estimated at 33 (Reference Anderson and TomensonAnderson & Tomenson, 1995). This modest advantage has to be set against the increased cost of SSRIs (Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment, 1997b ). A meta-analysis which subdivided TCAs according to whether they were reference compounds (e.g. the oldest TCAs, amitriptyline and imipramine) or newer tricyclics or hetero-cyclics, suggested that the higher drop-out rates associated with tricyclics could be attributed to the effect of amitriptyline and imipramine — newer tricyclics and heterocyclics were no worse than the SSRIs (Reference Hotopf, Hardy and LewisHotopf et al, 1997). However, there have not been any systematic reviews assessing amitriptyline v. other tricyclics and hetero-cyclics directly. We therefore aimed to test the hypothesis that amitriptyline would be less well tolerated than other tricyclics and SSRIs, and also to assess its effectiveness compared with the alternatives.

METHOD

Inclusion criteria

All RCTs comparing amitriptyline with any other tricyclic, heterocyclic or SSRI were included. Crossover studies were excluded. Studies adopting any criteria to define patients suffering from depression were included; a concurrent diagnosis of another psychiatric disorder was not considered an exclusion criterion. Trials in patients with depression with a concomitant medical illness were not included in this review.

Search strategy

Relevant studies were located by searching the Cochrane Collaboration Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Controlled Trials Register (CCDANCTR). This specialised register is regularly updated by electronic (Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, LILACS, Psyndex, CINAHL, SIGLE) and non-electronic literature searches. The register was searched using the following terms: AMITRIPTYLIN* or AMITRIL or ELATROL or ELAVIL or EMITRIP or ENDEP or ENOVIL or LAROXYL or LENTIZOL or LEVATE or MEVARIL or NOVOTRIPTYN or SAROTEN or TRYPTAL or TRYPTIZOL or TRIPTAFEN*. A specific electronic search was also performed with Medline and Embase from 1966 to 1998. We used the search term: AMITRIPTYLINE and RANDOMISED CONTROLLED TRIAL or RANDOM ALLOCATION or DOUBLE-BLIND METHOD. Reference lists of relevant papers and previous systematic reviews were hand searched for published reports and citations of unpublished research. Finally, attempts were made to obtain data through direct contact with the pharmaceutical industry.

Outcomes

Efficacy was evaluated using the following outcome measures:

-

(a) Number of patients who responded to treatment out of the total number of randomised patients.

-

(b) Group mean scores at the end of the trial on Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS; Reference HamiltonHamilton, 1960), or Montgomery and Åsberg Depression Scale (MADRS; Reference Montgomery and ÅsbergMontgomery & Åsberg, 1979), or any other depression scale.

Tolerability was evaluated using the following outcome measures:

-

(a) Number of patients failing to complete the study as a proportion of the total number of randomised patients.

-

(b) Number of patients complaining of side-effects out of the total number of randomised patients.

Data extraction

Using a standard form two reviewers independently extracted information on the year of publication, concealment of allocation, blindness, length of treatment, inclusion criteria, age range, country and setting of the study and type of pharmacological intervention. The number of patients undergoing the randomisation procedure, the number of patients who failed to complete the study (drop-outs) and that of patients complaining of side-effects were recorded. For dichotomous outcomes the number of patients showing a 50% reduction in score on the HDRS or MADRS scale was extracted; if these figures were not available, we extracted the number of patients categorised as ‘much improved’ and ‘improved’ on the Clinical Global Impression scale (CGI; Reference GuyGuy, 1976), or the number of patients in the corresponding categories of any other rating scale if the CGI was not used. For continuous outcomes the mean scores at end-point on the HDRS and the number of patients included in this analysis were recorded. If the HDRS was not employed, we extracted the mean scores at end-point on the MADRS or on any other rating scale. Mean scores were recorded with the standard deviation (s.d.) or standard error (s.e.) of these values. When only the s.e. was reported, it was converted into s.d. according to Altman & Bland (Reference Altman and Bland1996).

Statistical analysis

Efficacy data were analysed in the following way. Responders to treatment were calculated on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis: drop-outs were always included in this analysis. When data on drop-outs were carried forward and included in the efficacy evaluation (last observation carried forward, LOCF), they were analysed according to the primary studies; when drop-outs were excluded from any assessment in the primary studies they were considered as ‘drug failures’. Scores from continuous outcome scales could not be analysed on an ITT basis. This approach was not feasible as most studies performed only an end-point or LOCF analysis, which inevitably excluded most drop-out patients. Therefore, scores from continuous outcomes were analysed on an end-point basis, including only patients with a final assessment or with an LOCF to the final assessment. Tolerability data were analysed by calculating the proportion of patients who failed to complete the study and who experienced adverse reactions out of the total number of randomised patients. For each outcome measure three separate meta-analyses were planned. The first compared amitriptyline with tricylic/heterocyclic antidepressants, the second amitriptyline with SSRIs and the third analysis summarised the overall comparison of amitriptyline with both tricyclic/heterocyclic drugs and SSRIs.

Dichotomous outcomes were summarised by calculating a Peto-weighted odds ratio for each study, together with the 95% CI. An overall odds ratio was then calculated as a summary measure. The number of patients who need to be treated (NNT) with amitriptyline rather than the control antidepressants for one additional patient to benefit (NNTB) or be harmed (NNTH) was calculated with the 95% CI (Reference AltmanAltman, 1998). Heterogeneity of treatment effects between studies was tested using the χ2 statistic. Continuous outcomes were analysed by calculating a standardised weighted mean difference (SMD) for each study. This measure gives the effect size of an intervention in units of standard deviation so that scores from different outcome scales can be combined into an overall estimate of effect. A random effects model, which takes into consideration any between-study variation, was adopted to combine the effect sizes. Calculations were performed using the RevMan software provided by the Cochrane Collaboration (Review Manager, 1999).

RESULTS

Characteristics of included studies

We identified 352 potentially relevant studies: 186 RCTs met the inclusion criteria and were considered in this review (see Appendix), while 166 studies were excluded for the reasons listed in Table 1. Of the 186 included studies, 146 compared amitriptyline with another TCA or heterocyclic antidepressant and 40 compared amitriptyline with one of the SSRIs. In six studies amitriptyline was administered in combination with perphenazine; in two of these studies the experimental drug was nortriptyline in combination with fluphenazine. One trial compared amitriptyline with nortriptyline plus fluphenazine.

Table 1 Studies identified by the electronic search but excluded from the meta-analysis, and reason for exclusion

Although all trials reported that patients had been randomly allocated, in six cases the concealment of allocation was inadequate with some bias possible. In four studies only physicians, but not patients, were blind to treatments, in nine cases neither physicians nor patients were blind, while the other 173 studies were double-blind. The median sample size was 50 patients (10% percentile 24, 25% percentile 40, 75% percentile 80, 90% percentile 153; range 10-531). The median length of trials was four weeks (25% percentile 4, 50% percentile 4, 75% percentile 6; range 3-12); the number of studies with more than four weeks of follow-up increased from 28 (30%) to 62 (67%) after 1980. In 67 trials (36%) authors adopted diagnostic criteria and a specification of severity of depression to enrol patients; in 55 trials (30%) authors adopted only a specification of severity, while in the remaining 34% of studies patients were enrolled on the basis of physicians' implicit criteria to define patients with depression or because they were judged to require antidepressant therapy. Fifty-nine per cent of studies published before 1980 used implicit criteria v. 9.6% of those published after this date. Overall, 108 trials (60%) used operational criteria for depression. Nearly half of the studies (47%) provided a comprehensive description of patients' side-effects, while 23 (12%) trials gave inadequate details. The outcome assessment was performed with valid and reliable instruments in 70% of the sample; the use of valid instruments in studies published before and after 1980 increased from 51 (55%) to 81 (86%).

Efficacy of amitriptyline

Data extracted from 82 RCTs showed that the proportion of patients who responded to amitriptyline was 2.4% higher than for control TCA/heterocyclic antidepressants (NNTB 42, 95% CI NNTH 357 to ∞ to NNTB 20) (see Table 2). This difference corresponds to an overall odds ratio which favoured amitriptyline (Peto odds ratio 1.11, 95% CI 0.99-1.25), but with only borderline statistical significance. The estimate of the efficacy of amitriptyline and control TCAs/heterocyclic antidepressants on a continuous outcome, performed on 699 and 661 patients respectively, revealed an effect size which also significantly favoured amitriptyline (SMD=0.177, 95% CI 0.005-0.350). Head-to-head comparisons indicated that amitriptyline, in comparison with imipramine, is associated with a greater proportion of responders; in comparison with dothiepin, however, the proportion of responders was significantly lower (see Table 2).

Table 2 Amitriptyline (AMI) in comparison with tricyclic (TCA) or heterocyclic antidepressants: proportion of responders, number of patients evaluated on a continuous outcome and estimates of efficacy

| Responders/total randomised1 | Patients evaluated on a continuous outcome2 | Responders (intention to treat) Peto-odds ratio3 | Mean score at end-point SMD4 (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (No. of trials) | TCA | AMI | (No. of trials) | TCA | AMI | |||

| Control TCA/heterocyclic drug | ||||||||

| Amineptine | (1) | 21/26 | 14/25 | (2) | 42 | 47 | 0.32 (0.10-1.04) | 0.397 (-2.78 to 3.58) |

| Amoxapine | (11) | 180/298 | 199/303 | (1) | 17 | 21 | 1.28 (0.91-1.81) | 0.099 (-0.54 to 0.74) |

| Clomipramine | (1) | 20/35 | 13/37 | (1) | 35 | 37 | 0.42 (0.17-1.05) | -0.236 (-0.70 to 0.23) |

| Desipramine | (3) | 41/77 | 39/69 | (2) | 43 | 39 | 1.20 (0.62-2.31) | 0.422 (-0.01 to 0.86) |

| Dothiepin | (5) | 87/114 | 74/116 | (2) | 46 | 47 | 0.54 (0.31-0.96) | 0.015 (-0.39 to 0.42) |

| Doxepin | (8) | 100/161 | 103/170 | (-) | 1.00 (0.63-1.59) | - | ||

| Imipramine | (9) | 141/285 | 177/293 | (-) | 1.71 (1.20-2.43) | - | ||

| Lofepramine | (6) | 129/189 | 116/187 | (3) | 57 | 54 | 0.75 (0.49-1.16) | -0.002 (-0.48 to 0.47) |

| Maprotiline | (12) | 217/343 | 207/340 | (5) | 71 | 68 | 0.90 (0.65-1.26) | 0.324 (-0.06 to 0.71) |

| Mianserin | (5) | 70/133 | 65/109 | (3) | 39 | 38 | 1.37 (0.82-2.29) | 0.252 (-0.20 to 0.71) |

| Minaprine | (1) | 15/30 | 17/30 | (1) | 28 | 30 | 1.30 (0.48-3.56) | 0.173 (-0.34 to 0.69) |

| Nortriptyline | (4) | 55/104 | 55/93 | (2) | 33 | 32 | 1.36 (0.77-2.40) | -0.140 (-0.63 to 0.35) |

| Protriptyline | (1) | 17/51 | 27/49 | (-) | 2.40 (1.09-5.26) | - | ||

| Tianeptine | (2) | 204/285 | 218/280 | (1) | 103 | 108 | 1.40 (0.95-2.06) | 0.180 (-0.09 to 0.45) |

| Trazodone | (7) | 149/271 | 149/276 | (4) | 145 | 98 | 0.94 (0.66-1.33) | 0.273 (0.01 to 0.54) |

| Trimipramine | (1) | (/13 | 7/13 | (1) | 17 | 17 | 0.54 (0.11-2.52) | 0.251 (-0.42 to 0.93) |

| Viloxazine | (3) | 25/57 | 35/60 | (1) | 23 | 25 | 1.76 (0.84-3.67) | 0.379 (-0.19 to 0.95) |

| Combination | (2) | 25/68 | 17/37 | (-) | 1.59 (0.69-3.71) | - | ||

| Overall comparison | 1.11 (0.99-1.25) | 0.177 (0.005-0.350) | ||||||

| Test of heterogeneity | χ2=108.4 (d.f.=81), Z=1.78, P<0.05 | χ2=63.2 (d.f.=28), Z=2.01, P<0.05 | ||||||

Data from 17 RCTs showed that the proportion of patients who responded to amitriptyline was 2.8% higher than for SSRIs (NNTB 35, 95% CI NNTH 53 to ∞ to NNTB 13) (see Table 3). This difference corresponded to an overall odds ratio which favoured amitriptyline (Peto odds ratio 1.14, 95% CI 0.92-1.38), but not significantly. The estimate of the efficacy of amitriptyline and SSRIs on a continuous outcome, performed on 1041 and 1061 patients, respectively, revealed a small effect size which significantly favoured amitriptyline (SMD=0.106, 95% CI 0.02-0.19). No significant differences emerged from direct comparisons between amitriptyline and one of the SSRIs (see Table 3).

Table 3 Amitriptyline (AMI) in comparison with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): proportion of responders, number of patients evaluated on a continuous outcome and estimates of efficacy

| Responders/total randomised1 | Patients evaluated on a continuous outcome2 | Responders (intention to treat) | Mean score at end-point | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (No. of trials) | SSRI | AMI | (No. of trials) | SSRI | AMI | Peto odds ratio3 (95% CI) | SMD4 (95% CI) | |

| Control SSRI | ||||||||

| Fluoxetine | (5) | 77/146 | 70/145 | (9) | 336 | 341 | 0.83 (0.52-1.33) | 0.113 (-0.04 to 0.27) |

| Fluvoxamine | (1) | 16/35 | 22/34 | (2) | 40 | 43 | 2.13 (0.83-5.46) | 0.291 (-0.41 to 0.99) |

| Sertraline | (-) | (2) | 173 | 174 | - | 0.109 (-0.10 to 0.32) | ||

| Paroxetine | (9) | 266/487 | 267/455 | (7) | 468 | 483 | 1.21 (0.93-1.58) | 0.114 (-0.04 to 0.27) |

| Citalopram | (2) | 104/206 | 112/210 | (1) | 24 | 20 | 1.11 (0.76-1.63) | -0.077 (-0.67 to 0.52) |

| Overall comparison | 1.14 (0.94-1.38) | 0.106 (0.02-0.19) | ||||||

| Test of heterogeneity | χ2=11.27 (d.f.=16), Z=1.31, P=0.79 | χ2=19.65 (d.f.=20), Z=2.42, P=0.48 | ||||||

Tolerability of amitriptyline

Data from 125 RCTs showed that 20% of patients treated with amitriptyline failed to complete the study, in comparison with 21.5% of patients who received another tricyclic/heterocyclic antidepressant (NNTB=69, 95% CI NNTH 385 to ∞ to NNTB 32). This difference corresponded to an overall odds ratio non-significantly favouring amitriptyline (Peto odds ratio 1.09, 95% CI 0.98-1.22) (see Table 4). However, the estimate of the proportion of patients who experienced side-effects during the study was 13% higher for amitriptyline than for control TCAs/heterocyclic antidepressants (NNTH=7.6, 95% CI NNTH 6 to NNTH 11) (see Table 4), corresponding to an odds ratio which significantly favoured the control TCAs/heterocyclic antidepressants. Head-to-head comparisons failed to detect statistically significant differences in terms of drop-outs between amitriptyline and one of the TCA/heterocyclic antidepressants (see Table 4). However, amitriptyline was associated with more side-effects than dothiepin, maprotiline, mianserin, minaprine and nortriptyline (see Table 4).

Table 4 Amitriptyline (AMI) in comparison with tricylcic/heterocyclic antidepressants (TCAs): proportion of drop-outs, proportion of patients with side-effects and estimates of tolerability

| Responders/total randomised1 | Patients evaluated on a continuous outcome2 | Drop-outs3 | Patients with side-effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (No. of trials) | TCA | AMI | (No. of trials) | TCA | AMI | Peto odds ratio4 (95% CI) | Peto odds ratio4 (95% CI) | |

| Control TCA/heterocyclic | ||||||||

| Amineptine | (2) | 8/48 | 7/47 | (1) | 6/26 | 10/25 | 1.14 (0.38-3.39) | 0.46 (0.14-1.49) |

| Amoxapine | (13) | 94/359 | 89/363 | (3) | 59/97 | 63/95 | 1.09 (0.77-1.54) | 0.77 (0.41-1.44) |

| Clomipramine | (3) | 73/148 | 59/151 | (1) | 18/35 | 16/37 | 1.52 (0.95-2.41) | 1.38 (0.55-3.47) |

| Desipramine | (4) | 10/82 | 13/74 | (-) | 0.72 (0.28-1.84) | - | ||

| Dothiepin | (8) | 12/196 | 18/200 | (5) | 51/115 | 70/119 | 0.68 (0.32-1.47) | 0.51 (0.29-0.88) |

| Doxepin | (13) | 88/427 | 103/433 | (4) | 46/76 | 61/92 | 0.84 (0.60-1.17) | 0.77 (0.39-1.50) |

| Imipramine | (6) | 25/172 | 24/177 | (2) | 17/71 | 25/85 | 1.34 (0.71-2.51) | 0.73 (0.35-1.50) |

| Lofepramine | (8) | 54/236 | 61/234 | (2) | 12/31 | 19/31 | 0.85 (0.55-1.32) | 0.39 (0.14-1.08) |

| Maprotiline | (18) | 86/557 | 88/550 | (7) | 136/224 | 154/212 | 0.97 (0.69-1.35) | 0.59 (0.40-0.88) |

| Mianserin | (12) | 123/410 | 96/377 | (3) | 73/135 | 101/131 | 1.27 (0.91-1.77) | 0.34 (0.20-0.57) |

| Minaprine | (2) | 115/429 | 31/162 | (2) | 117/429 | 67/162 | 1.50 (0.98-2.29) | 0.55 (0.37-0.82) |

| Nomifensine | (1) | 1/17 | 1/12 | (-) | 0.69 (0.04-12.1) | - | ||

| Nortriptyline | (8) | 27/235 | 26/232 | (4) | 42/124 | 52/102 | 1.01 (0.56-1.83) | 0.51 (0.30-0.87) |

| Protriptyline | (-) | (1) | 38/51 | 33/49 | - | 1.41 (0.60-3.33) | ||

| Tianeptine | (3) | 80/349 | 65/345 | (-) | 1.28 (0.89-1.85) | - | ||

| Trazodone | (10) | 79/357 | 72/362 | (2) | 53/113 | 54/110 | 1.14 (0.79-1.65) | 0.92 (0.54-1.55) |

| Trimipramine | (2) | 11/58 | 13/57 | (1) | 3/21 | 5/20 | 0.76 (0.30-1.97) | 0.51 (0.11-2.36) |

| Viloxazine | (7) | 24/140 | 21/148 | (1) | 14/19 | 16/22 | 1.32 (0.69-2.55) | 1.05 (0.27-4.12) |

| Combinations | (5) | 84/409 | 32/164 | (1) | 68/89 | 37/46 | 1.05 (0.66-1.69) | 0.79 (0.34-1.86) |

| Overall comparison | 1.09 (0.98-1.22) | 0.62 (0.53-0.73) | ||||||

| Test of heterogeneity | χ2=118.1 (d.f.=109) | χ2=53.3 (d.f.=39) | ||||||

| Z=1.60, P<0.05 | Z=5.90, P=0.06 | |||||||

Data from 40 RCTs comparing amitriptyline and SSRIs showed that 29.8% of patients treated with amitriptyline failed to complete the study, in comparison with 27.7% of patients treated with SSRIs (NNTH=49, 95% CI NNTB 180 to ∞ to NNTH 22). This difference corresponds to an overall odds ratio of 0.86 (95% CI 0.75-0.98), which significantly favoured SSRIs (see Table 5). The estimate of the proportion of patients who experienced side-effects during the study was 11.6% higher for amitriptyline than for SSRIs (NNTH=8.6, 95% CI NNTH 6 to NNTH 15) (see Table 5), corresponding to an odds ratio which significantly favoured the SSRIs.

Table 5 Amitriptyline (AMI) in comparison with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): proportion of drop-outs, proportion of patients with side-effects and estimates of tolerability

| Drop-outs/total randomised1 | Patients with side-effects/total randomised2 | Drop-outs | Patients with side-effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (No. of trials) | SSRI | AMI | (No. of trials) | SSRI | AMI | Peto odds ratio3 (95% CI) | Peto odds ratio3 (95% CI) | |

| SSRI | ||||||||

| Fluoxetine | (15) | 124/540 | 148/551 | (1) | 7/20 | 16/21 | 0.79 (0.59-1.04) | 0.20 (0.06-0.66) |

| Fluvoxamine | (3) | 17/81 | 19/77 | (-) | 49/115 | 52/113 | 0.84 (0.39-1.83) | - |

| Sertraline | (6) | 264/650 | 228/568 | (2) | 221/366 | 251/360 | 0.97 (0.76-1.23) | 0.87 (0.50-1.50) |

| Paroxetine | (13) | 205/897 | 217/882 | (4) | 131/206 | 169/210 | 0.89 (0.71-1.12) | 0.70 (0.51-0.96) |

| Citalopram | (3) | 55/230 | 75/230 | (2) | 0.64 (0.42-0.96) | 0.43 (0.28-0.66) | ||

| Overall comparison | 0.86 (0.75-0.98) | 0.61 (0.48-0.76) | ||||||

| Test of heterogeneity | χ2=49.6 (d.f.=39), Z=2.27, P=0.11 | χ2=14.7 (d.f.=8), Z=4.35, P=0.06 | ||||||

Overall efficacy and tolerability of amitriptyline in comparison with all antidepressant drugs

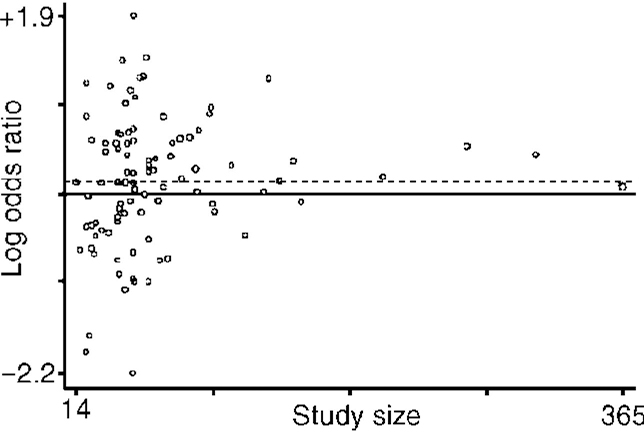

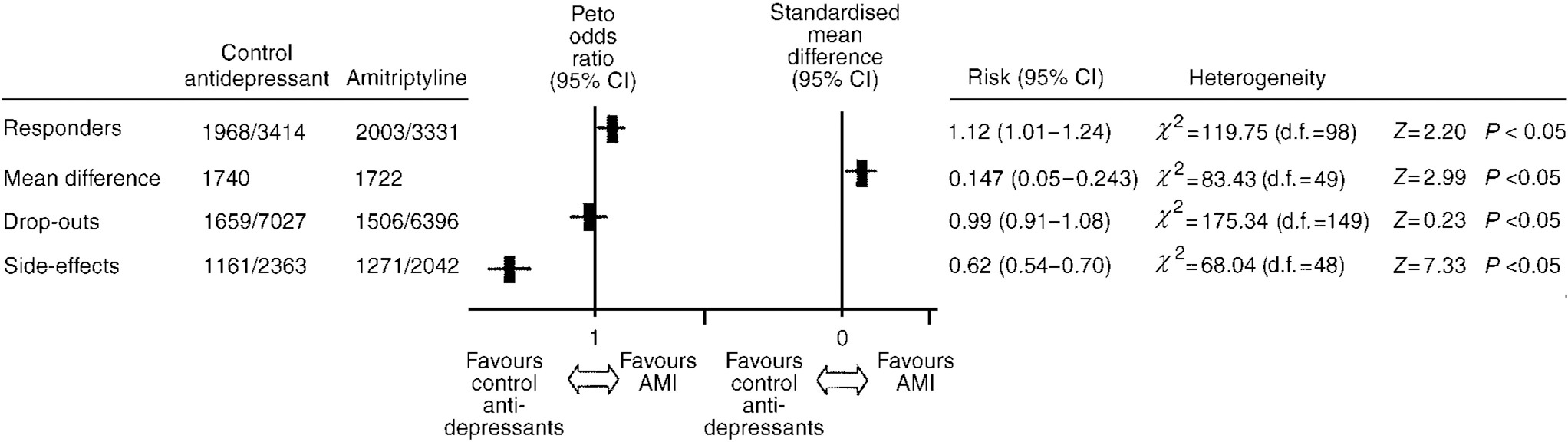

A funnel plot (Fig. 1) showed no evidence of publication bias being a problem in the data collected. The overall estimate of the efficacy of amitriptyline in comparison to TCAs/heterocyclic drugs and SSRIs showed a 2.5% difference in the proportion of responders in favour of amitriptyline (NNTB=40, 95% CI NNTB 21 to NNTB 694) (see Fig. 2), which corresponded to an intention to treat odds ratio of 1.12 (95% CI 1.01-1.24). The estimate of the efficacy of amitriptyline and control antidepressants on a continuous outcome confirmed the slightly superior efficacy profile of amitriptyline: the estimate of the SMD significantly favours amitriptyline (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 1 Funnel plot of estimated logarithmic odds ratio against the size of the study. Broken horizontal line represents the overall estimate of the logarithmic odds ratio (0.11).

Fig. 2 Overall estimate of the efficacy and tolerability of amitriptyline (AMI) in comparison to all other antidepressant drugs.

The drop-out rate in patients taking amitriptyline and the control antidepressants was very similar, yielding an overall odds ratio of 0.99 (95% CI 0.91-1.08). However, the estimate of the proportion of patients who experienced side-effects during the study was 13.1% higher for amitriptyline than control antidepressants (NNTH=7.6, 95% CI NNTH 6 to NNTH 10), corresponding to an odds ratio which significantly favoured the control antidepressants (see Fig. 2).

DISCUSSION

Implications for research

This systematic review suggests that amitriptyline should remain in its position as the gold-standard antidepressant. Using a highly conservative approach to estimate efficacy — in which drop-outs were included in the analysis — we estimated that amitriptyline is slightly more efficacious than all other antidepressants grouped together. The same applied when the analysis was subdivided according to pharmacological class of the comparison drug — although the comparison with SSRIs failed to reach statistical significance. This measure of outcome takes into consideration drop-outs from therapy, so it cannot be explained by differential completion of the study protocol. The additional efficacy outcome — using effect sizes of continuous outcomes — showed a similar picture, but now with a statistically significant difference against the SSRIs. The tolerability data confirm that amitriptyline is associated with more side-effects than, but similar drop-outs to, other TCAs, and more side-effects and more drop-outs than SSRIs.

Methodological concerns

There are reasons for interpreting these results with caution. Included studies are heterogeneous in terms of selection criteria, allocation concealment, setting and out-come measures. A certain variability in the overall quality of the primary research might therefore have influenced the overall comparison. This systematic review did not investigate heterogeneity by grouping trials according to patient characteristics or trial quality and performing subgroup analyses. This approach was not adopted because it would have inevitably decreased the power of the analysis, thus providing ambiguous results; in addition, increasing the number of comparisons would have increased the possibility of detecting significant differences only by chance. The present analysis, which pools data from different trials carried out in many populations, has the advantage of generating information which can be applied to a very diverse range of patients (Reference Oxman, Cook and GuyattOxman et al, 1994).

Implications for practice

How should these data be translated into clinical practice? It certainly seems reasonable to conclude that amitriptyline is as good as — if not better than — the other TCAs and heterocyclic antidepressants, with the possible exception of dothiepin (Reference Eccles, Freemantle and MasonEccles et al, 1999). It seems reasonable to suggest that either amitriptyline or dothiepin should remain the first-line TCA. More controversial is the role of TCAs alongside SSRIs. The results from randomised trials suggest that amitriptyline probably has the edge in terms of efficacy over SSRIs. Given that publication bias is likely to work in favour of newer compounds, it is possible that unpublished data would further improve amitriptyline's position. Those who advocate first-line use of an SSRI point to two additional strands of evidence — the danger of TCAs in overdose and the fact that they are often in practice prescribed at sub-therapeutic doses. Although the widespread prescribing of SSRIs has to be viewed as a public health measure to prevent suicide, it is likely to be prohibitively expensive; in addition, data showing that the widespread use of SSRIs decreases suicide rates are lacking (Reference Barbui, Campomori and D'AvanzoBarbui et al, 1999). The advice should probably remain that SSRIs are the first-line treatment to be given to patients at high risk of committing deliberate self-harm. The problems of TCAs being prescribed in low doses has attracted considerable attention, as evidence suggests that in real situations TCAs are rarely taken appropriately. However, the guidelines on ‘adequate’ dosing — which suggest at least 125 mg of amitriptyline have to be prescribed for it to be effective — are themselves based on inadequate research. Recent systematic reviews indicate that low-dose TCAs are as effective as SSRIs in treating depression (Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment, 1997a ), and studies directly comparing low- and high-dose TCAs show only very modest benefits of high doses (Reference Bollini, Pampallona and TibaldiBollini et al, 1999).

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ Amitriptyline is at least as effective as the other tricyclic and heterocyclic antidepressants.

-

▪ Slightly more patients treated with amitriptyline make a recovery than with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

-

▪ Amitriptyline is less well tolerated than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ Included trials are heterogeneous in terms of patients, settings and outcome measures.

-

▪ Heterogeneity has not been investigated by performing subgroup analyses.

-

▪ The variability in the quality of the original studies might have influenced the overall comparison.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Hugh McGuire, CCDANCTR Trial Search Coordinator, for assisting in developing the search strategy of this research. Thanks in addition to Nick Freemantle for sharing relevant references and to Jennifer Hillebrand for assistance in extracting data from non-English articles.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.