Introduction

Statutory minimum wages have become a popular policy instrument in the last few decades. From a global perspective, 90 percent of all countries now have some kind of legally set minimum wage for all or at least a portion of their private-sector employees (ILO, 2017). Historically, minimum wages were implemented at the beginning of the 20th century as part of policy packages to protect workers against adverse working conditions, including excessive working hours, unsanitary workplaces and unduly low pay (Neumark and Wascher, Reference Neumark and Wascher2008). In recent years, minimum wages have also attracted attention as a policy instrument to alleviate the income hardships of low-wage workers more broadly and to address issues of wage and income inequality along with in-work poverty (ILO, 2017; Leventi et al., Reference Leventi, Sutherland and Tasseva2017; McKnight et al., Reference McKnight, Stewart, Himmelweit and Palillo2016; OECD, 2015). The introduction of a National Living Wage in the United Kingdom, which will reach 60 percent of the median hourly wage in 2020, and the “Fight for 15” campaign in the United States, which rallies for an increase in the US federal minimum wage from the current rate of 7.25 US Dollars to 15 US Dollars per hour are probably the most well-known examples of a renewed interest in raising minimum wages. Within the European Union, minimum wages attracted renewed interest with the “fair wage” provisions in the European Pillar of Social Rights (EPSR) in 2017. One specific aspect of the minimum wage in this context was the so-called working poor, who, despite their participation in the labour market, depend on social welfare benefits. Although the UK government’s National Living Wage is lower and different in concept from original living wage concepts (see Prowse et al., Reference Prowse, Fells, Arrowsmith, Parker and Lopes2017 for an overview on the topic), its 60 percent target will be one of the highest statutory minimum wages in the industrialized world.

From an industrial relations perspective, minimum wages can be seen as a corrective political response to a growing dualisation of the labour market in which insiders’ status, in particular highly skilled workers in the core manufacturing or financial sectors with relatively high collective coverage and wages, remains relatively well protected. At the same time, the number of workers in non-standard jobs has been growing, particularly in the service sector, which has low collective coverage and low wages (Hassel, Reference Hassel2010, Reference Hassel2014; Palier and Thelen, Reference Palier and Thelen2010). Structural drivers that have contributed to this development have been deindustrialisation alongside increasing female labour market participation as well as a growing service sector and globalization, including international competition from low-wage countries (Emmenegger et al., Reference Emmenegger, Häusermann, Palier, Seeleib-Kaiser, Emmenegger, Häusermann, Palier and Seeleib-Kaiser2012). Additionally, the shift towards new welfare state policies emphasizing labour market participation over income protection have contributed to these new labour market inequalities (Bonoli and Natali, Reference Bonoli and Natali2012; Esping-Andersen et al., Reference Esping-Andersen, Gallie, Hemerijck and Myles2002; Taylor-Gooby et al., Reference Taylor-Gooby, Gumy and Otto2015).

Germany, which is a prominent example of these developments, introduced a general statutory minimum wage only in 2015. In our paper, we provide empirical evidence on the effects of the new wage floor on welfare receipt and (in-work) poverty. The evidence is based on our own descriptive analyses of various data sources and the results of a micro simulation. In addition, we review the existing literature concerning the causal effects identified so far for Germany. Our evidence, which is in line with findings from other countries, highlights the limitations of minimum wages as a social policy instrument even though they can be a relevant accompanying element to combat in-work poverty (Lohmann and Marx, Reference Lohmann and Marx2018). Our research can help policy-makers better understand the economic mechanisms and rationales with respect to the potential and limitation of minimum wages as an instrument to combat welfare receipt and (in-work) poverty.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: in the next section, we will describe the political and institutional background of the German statutory minimum wage. Section 3 discusses the main theoretical considerations and the empirical literature related to the effects of minimum wages on welfare receipt and (in-work) poverty. The empirical evidence on Germany is provided in section 4, followed by a discussion of these results and a brief conclusion.

Political background and institutional framework

The introduction of the general statutory minimum wage in Germany can be seen as a response to a significant decline in collective coverage, a growing low-wage sector and to the fundamental reorganization of the social welfare system between 2002 and 2005 when the so-called Hartz reforms came into force (Jacobi and Kluve, Reference Jacobi and Kluve2007; Kemmerling and Bruttel, Reference Kemmerling and Bruttel2006). While Germany was characterized by high levels of collective coverage across all industries until the late 1980 s, from 1996 to 2015 the share of establishments covered by collective agreements fell from 68 to 39 percent in Western Germany and from 55 to 28 percent in Eastern Germany (Oberfichtner and Schnabel, Reference Oberfichtner and Schnabel2019). Companies not covered by collective agreements and sectors with below-average coverage showed a particularly high incidence of low wages. The share of low-wage workers amounts to approximately 20 percent, which is among the highest in Europe (Bosch and Kalina, Reference Bosch, Kalina and Vaughan-Whitehead2010; McKnight et al., Reference McKnight, Stewart, Himmelweit and Palillo2016). One reason is so-called Minijobs. These are a specific form of employment in Germany in which employees can earn 450 Euros per month free of income tax and social security contributions; however, these jobs provide no health insurance and only optional pension insurance and are characterized by particularly low wages.

Following internal discussions between trade unions across industries, the German Trade Union Congress (DGB) called for the introduction of a national minimum wage of 7.50 Euro per hour in 2006, a demand that was raised to 8.50 Euro in 2010. The employers’ associations categorically opposed a national minimum wage. On the side of the political parties, the conservative-liberal government (2009 to 2013) also did not support the idea of a general statutory minimum wage, while Social Democrats, the Green party and the socialist Die Linke were in favour. It was only in the 2013 federal elections that all parties campaigned for a statutory national minimum wage of varying forms. While the suggested approaches differed considerably in terms of reach, levels and governance, there was by now a consensus across the political spectrum that legally binding wage floors were needed. Following the 2013 federal elections, Chancellor Merkel’s Christian Democrats and the Social Democrats formed a coalition and agreed to introduce a nationwide uniform minimum wage (see, for instance, Bosch, Reference Bosch2018 for more details regarding the political background of the minimum wage introduction; Marx and Starke, Reference Marx and Starke2017).

The general statutory minimum wage took effect on 1 January 2015 at an initial level of 8.50 Euro per hour. It covers all employees, with few exceptions (youths under 18 years of age, apprentices, certain categories of trainees and interns, the long-term unemployed in their first six months after starting a new job and nonprofit and/or voluntary workers). In addition, during a transition period that lasted until the end of 2017, wages below the statutory minimum wage were allowed in a few sectors with collectively agreed-upon minimum wages that are made generally binding by government decree.

The minimum wage directly affected the wages of approximately 4.0 million employees who earned less than 8.50 Euro before the introduction of the minimum wage. This corresponds to approximately 11.3 percent of the dependent workforce – with significant regional differences. In Western Germany, 9.3 percent of employees earned less than 8.50 Euro, and this figure was 20.7 percent in Eastern Germany. Measured by the Kaitz index, which defines the relationship between the minimum and median wage, the new German minimum in 2015 (48 percent) was roughly equal to that of the UK (49 percent) and the Netherlands (46 percent) (OECD, 2017).

Adjustments of the minimum wage are decided by an independent Mindestlohnkommission (Minimum Wage Commission) every two years. Its six members are nominated by the Bundesvereinigung der Deutschen Arbeitgeberverbände (BDA, Confederation of German Employers’ Associations) and Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund (DGB, German Trade Union Confederation), respectively. The independent chair is appointed based on their joint proposal. There are two additional academic advisory members without voting rights. The minimum wage has been increased twice since its introduction. By January 2017, it was increased to 8.84 Euro per hour; and by January 2019, to 9.19 Euro. By January 2020, there will be another increase, to 9.35 Euro. These increases have by and large followed the development of collective wages. The Kaitz index has thus not changed markedly.

The statutory minimum wage needs to be seen within the context of the German welfare regime. For the first 12 months preceding a job loss, workers are usually entitled to earnings-related unemployment insurance benefits, the so-called Arbeitslosengeld I (Unemployment Benefit I, UB I). If workers are not eligible for this benefit, for instance because they have not made sufficient contributions beforehand, or the maximum period for UB I has expired, they can apply for means-tested and household-based basic income benefits, including housing benefits, the so-called Arbeitslosengeld II (Unemployment Benefit II, UB II), colloquially also referred to as “Hartz IV”. UB II recipients as well as their working-age family members are required to actively look for jobs. UB II may also be paid in order to top-up wages that are below the household-specific level of UB II. Indeed, the statutory minimum wage level of 8.50 Euro was set to allow a full-time employed single person to earn enough to avoid unemployment benefit payments at that time. In 2015, a non-working single person received a net income from means-tested UB II of 737 Euro, which consisted of 399 Euro basic payments and an average of 338 Euro for housing costs. In the event that UB II recipients do take up employment, they are allowed to earn 100 Euro per month without an offset in their benefits. Above 100 Euro monthly gross wages, the benefit reduction rate ranges between 80 and 100 percent. Thus, working 38 hours per week at an hourly wage of 8.50 Euro, a single person would receive a gross income of approximately 1,400 Euro, leaving her with approximately 1,050 Euro net income.

Theoretical considerations and related empirical literature

The effect of minimum wage increases on welfare receipt and in-work poverty is theoretically ambiguous. In principle, the introduction or increase in a minimum wage will increase the hourly wages of those who have previous earnings below the new wage floor, which would ceteris paribus lead to higher incomes and thus less of a need to receive additional benefits. However, there are several caveats that may not translate this hourly wage increase into declining welfare receipt or (in-work) poverty.

In this respect, it is important to keep in mind the possible reactions of companies following the introduction of wage increases. If there are negative employment effects, these may increase overall welfare receipt due to an increasing number of unemployed. From an international perspective, the empirical evidence on employment effects is mixed. While some studies find significant negative effects – mostly limited to specific labour market groups such as teenagers – a consensus seems to have emerged among economists that, when set at an appropriate rate, minimum wages do not severely reduce employment levels (Dickens, Reference Dickens2015; Manning, Reference Manning2016). The British Low Pay Commission concludes, based on 15 years of research, that the national minimum wage ‘has led to higher than average wage increases for the lowest paid, with little evidence of adverse effects on employment or the economy’ (Low Pay Commission, 2015).

For Germany, the picture is similar (for an overview of the available evidence see Bruttel, Reference Bruttel2019, and Caliendo et al., Reference Caliendo, Schröder and Wittbrodt2019). If studies found any employment effects, they were – whether positive or negative – rather small in relation to the overall number of jobs. Studies usually differentiate between jobs subject to social security contributions and so-called Minijobs. The latter represents a specific form of employment introduced in 2003 in which employees can earn 450 Euros per month free of income tax and social security contributions, but they receive no health insurance and only optional pension insurance. Almost a dozen causal impact analyses have been published thus far, and these analyses consistently identified a reduction in the number of people who are exclusively employed in Minijobs. Regarding employment subject to social security contributions, the picture is more mixed. Some studies have found negative effects, while other studies have found positive or no significant effects. Nevertheless, the effects are small compared to the total number of jobs liable to pay social security contributions. Regarding overall employment (i.e. the sum of jobs subject to social security contributions and Minijobs), most studies detect a slightly negative effect due to the introduction of the minimum wage and attribute that trend to the reduction in the number of Minijobs. Thus, while the reductions in the employment levels are rather negligible, the initial evidence in Germany suggests that companies have reduced contractual working hours as a reaction to the increase in hourly wages. On the individual level, these reductions have partially offset the hourly wage increases, and monthly salaries partly remained the same (Mindestlohnkommission, 2018). Welfare receipt or in-work poverty generally refer to monthly income rather than hourly wages. Thus, given that we do not observe any major changes in monthly incomes, we do not expect many changes in the other parameters.

Welfare receipt and poverty are generally analysed at the household level, i.e. other members of the household must also be taken into account. The family income may come from different sources. Households receiving UB II, which include at least some non-working household members, most notably children, will not see their general need for social welfare end after the introduction of a minimum wage. In addition, labour supply preferences may change following a minimum wage introduction. Given that one household member now earns more, another may reduce its labour supply. This would result in a constant income and thus welfare receipt but more leisure for the total household.

Our brief review of the available empirical evidence is limited to European studies. The United States welfare regime substantially differs with respect to its support for low-income households, and particularly its level of income support for low-wage workers. Thus, US results provide only limited guidance for a European or German discussion regarding the effect of minimum wages on welfare receipt and in-work poverty (for an overview of US studies see Belman and Wolfson, Reference Belman and Wolfson2014; Dube, Reference Dube2018; Neumark and Wascher, Reference Neumark and Wascher2008). The empirical literature concerning the influence of minimum wages on welfare receipt in Germany or other European countries is rather scarce. In Germany, studies based on simulation models have tried to predict the ex ante effect of the introduction of the minimum wage. Bruckmeier and Wiemers (Reference Bruckmeier and Wiemers2014) estimated that while holding employment constant, approximately 60,000 of more than 1.0 million households receiving unemployment benefit II would lose their entitlement. The weighted disposable household income of those beneficiaries that earned below the new wage floor in the year prior to the minimum wage introduction would only increase by 10 to 12 Euros per month. Müller and Steiner (Reference Müller and Steiner2010) found similar results, indicating that, in Germany, a minimum wage would have a minimal impact on the net household income, inequality and poverty.

In contrast to welfare receipt, the effects of minimum wages on (in-work) poverty have been studied more intensely. However, most European studies have only used simulation models rather than ex post empirical evaluations. These simulation studies have generally found very small and/or statistically insignificant effects. For the United Kingdom, Sutherland (2001) found that the introduction of the National Minimum Wage reduced poverty by 1.2 percentage points, while the effects of tax-benefit changes were much higher. Atkinson et al. (Reference Atkinson, Leventi, Nolan, Sutherland and Tasseva2017) simulate different policy options for the United Kingdom to reduce inequality and poverty and find the National Living Wage to be of rather small significance compared to other measures such as tax reforms or raising child benefits. For Belgium, Marx et al. (Reference Marx, Vanhille and Verbist2012) conclude that even quite large increases in the minimum wage would have a limited impact on in-work poverty compared to other policy options. Matsaganis et al. (Reference Matsaganis, Medgyesi and Karakitsios2015) analyse the effects on the 28 EU member states if the minimum wage were raised to 50 percent of national average hourly wages and find positive but modest effects in most countries. Leventi et al. (Reference Leventi, Sutherland and Tasseva2017) look at seven diverse European countries and compare different policy instruments. They find rather minor effects of minimum wages on poverty.

Empirical Evidence

In what follows, we provide quantitative empirical evidence from Germany following the introduction of the statutory minimum wage in 2015. We not only report on the development of welfare receipt and poverty rates but also complement the findings with figures that may explain the observed developments.

Welfare receipt

At the time of the minimum wage introduction, approximately 1.2 million workers received additional UB II. As we will show, their number has only decreased marginally. The main reason can be seen in the composition of working UB II recipients. Few are single-full time workers for whom the minimum wage would allow them to end their UB II receipt. In addition, low working hours rather than low hourly wages are often at the core of explaining in-work welfare receipt.

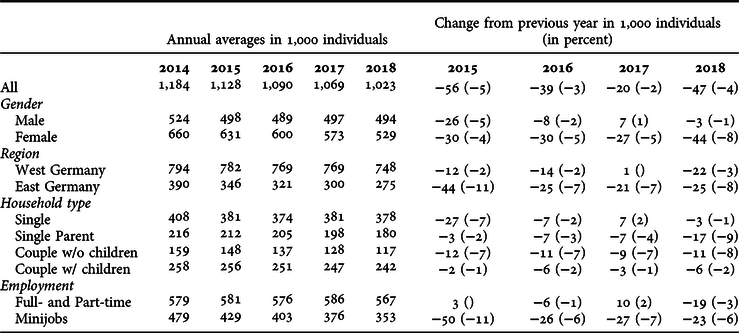

Since the introduction of the statutory minimum wage in 2015, the number of individuals who, despite being employed, are eligible for supplementary UB II, also known as “Aufstocker”, decreased from 1,184 thousand in 2014 to 1,023 thousand in 2018, which corresponds to an annual decrease of 3.6 percent. Figures started to decline before the introduction of the minimum wage. Between 2010 and 2014, the number of “Aufstocker” decreased at an annual rate of 1.7 percent. Since 2014, above-average decreases can be observed for females, in Eastern Germany, in couple households without children and for those working in Minijobs (see Table 1). Given the robust general economic and labour market conditions in this period – the total number of unemployed UB II recipients declined from 1,965 thousand in 2014 to 1,538 thousand in 2018 – we will discuss to what extent the decline can be attributed to the minimum wage or other factors.

Table 1. Development of employed UB II recipients between 2014 and 2018 by subgroups

Note: The figures on household type and employment do not add up to the total number of employed UB II recipients due to an undefined status (household type) or missing information (employment)

Source: Statistics of the Federal Employment Agency, own calculations. Note: Data do not include self-employed.

Two studies attempting to identify the causal effect of the minimum wage introduction based on a difference-in-difference approach are available thus far. Both use employment data from the Statistics of the German Federal Employment Agency. Bruckmeier and Becker (Reference Bruckmeier and Becker2018) find that the reductions of “Aufstocker” cannot be traced back to the introduction of the minimum wage. Schmitz (Reference Schmitz2017), however, finds a small minimum wage-induced reduction in the number of “Aufstocker” by approximately 38 thousand, which was partially offset by a minimum wage-induced increase in the number of non-working recipients by 19 thousand.

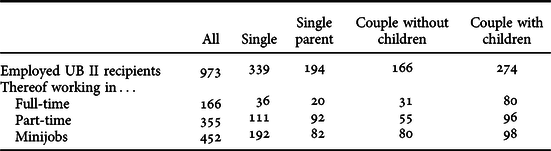

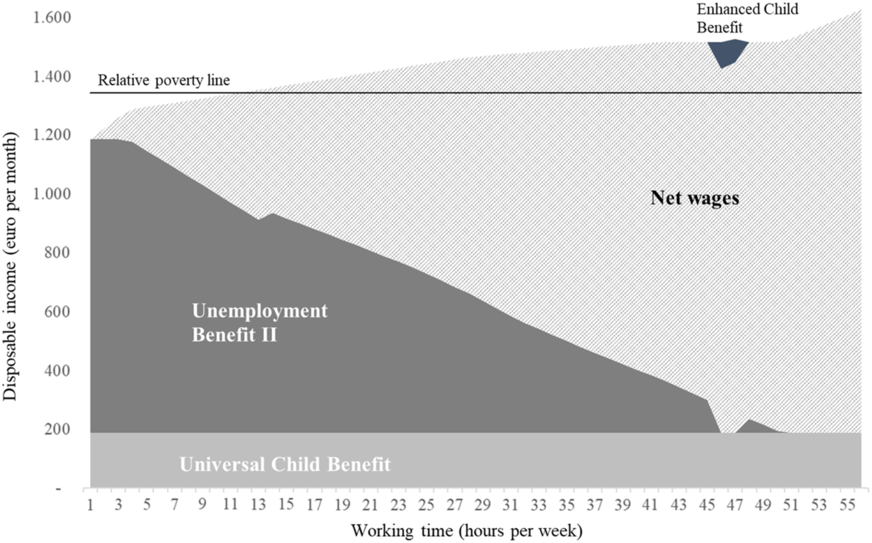

This low and partly insignificant decrease in the number of “Aufstocker” can be explained by the analysis of the composition of working UB II recipients. When the minimum wage was introduced, its level was set to allow a full-time employed single person to earn enough to avoid UB II. However, from approximately 1.2 million employed individuals receiving supplementary UB II at the end of 2014, only approximately 36 thousand, i.e. approximately 3 percent, fit into this category of full-time employed singles. Most individuals worked part-time or in Minijobs (Table 2). Given the limited number of working hours in most benefit-receiving households, any reasonable minimum wage level would not be sufficient to help these households escape welfare receipt. In particular, among single parents, care responsibilities are a major factor that explains the low working hours of single parents receiving UB II (Lietzmann, Reference Lietzmann2014).

Table 2. Number of employed UB II recipients by household type and type of employment (as of December 2014, in 1,000 individuals)

Source: Statistics of the Federal Employment Agency.

Note: Data do not include self-employed (117 thousand), employees with unknown types of employment (121 thousand) and apprentices (34 thousand).

Table 2 also shows a second – but somewhat linked – reason for receiving UB II benefits even if one is working. Households often include more than the individual receiving UB II but also non-working household members, most notably children. Approximately half of all employed UB II recipients live in households with children. These “Aufstocker” receive benefits to cover their additional living costs for their non-working family members.

For many “Aufstocker”, it is indeed not necessarily a low hourly wage but low working hours that cause them to receive UB II. As shown in Figure 1, the median gross hourly wage of full or part-time working UB II recipients before the minimum wage introduction was 8.65 Euro and thus a relevant proportion of those people earned above the introductory rate of 8.50 Euro (see also Brenke and Müller, Reference Brenke and Müller2013, for similar results based on the German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP)). Even though the differences among the household types are not statistically significant at the 95 percent level, the results indicate that lone parents have the highest hourly wages among all household types. Hourly wages for those working in Minijobs were lower for all household types, reflecting a general lower wage level in these jobs (Mindestlohnkommission, 2018). The pattern for lone parents is similar to that reported by Sabia (Reference Sabia2008) in his study on single mothers, where the majority earn far above the minimum wage while not working full-time.

Figure 1. Median gross hourly wage of working UB II recipients 2014 by household type (in Euro).

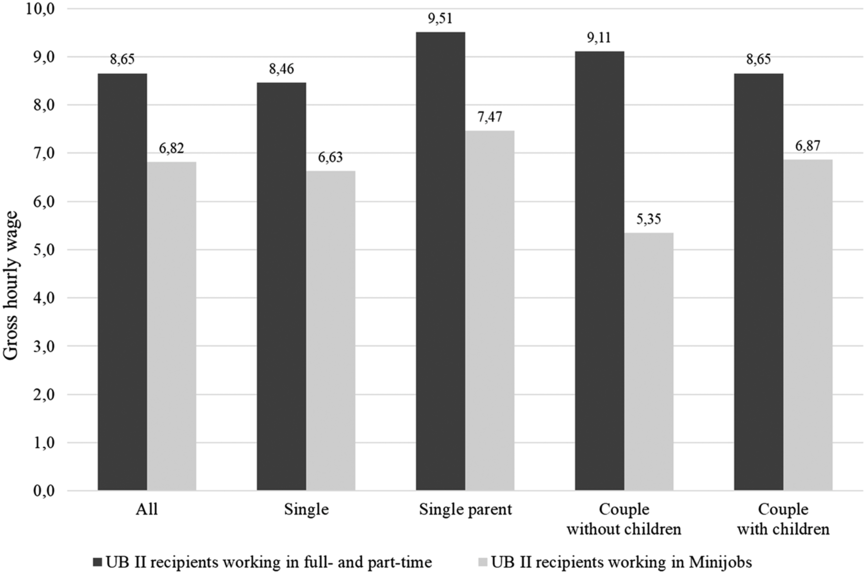

To illustrate the interplay between household size, working time and benefit receipt, we simulate hypothetical budget constraints for an example household using the microsimulation model of the IAB (see Arntz et al., Reference Arntz, Clauss, Kraus, Schnabel, Spermann and Wiemers2007, and Bruckmeier and Wiemers, Reference Bruckmeier and Wiemers2018, for details about the model). Figure 2 presents the net income development for a single parent household working at the minimum wage in relation to her working hours. The simulations reflect the German tax-benefit-system of the year 2015 and assume that the household claims all benefits to which it is entitled. While the net earned income increases with hours worked according to the income tax and social security contributions, the total disposable income of the household only increases very slowly. This is due to the high effective marginal tax rates observed for households receiving UB II, as the benefit reduction rates in the phase-out range of UB II are between 80 and 100 percent. This illustrates a weak point known from other benefit systems; i.e. the reduced incentive for welfare recipients to increase their work volume (see, for instance, Blundell, Reference Blundell2012). This situation contributes to the observed low work intensity of UB II recipients. The micro simulation also illustrates the relevance of the household composition. For instance, a single parent with one child would need to work almost 45 hours a week at the minimum wage to avoid means-tested UB II transfers. To address this aspect, the government has recently decided to implement several reforms to facilitate access to benefits by households with children prior to basic income support (i.e. means-tested housing allowance and enhanced child benefit).

Figure 2. Budget constraints and income components for a single parent working at the minimum wage and living with one dependent child in the household by weekly working time (2015)

We have previously said that the minimum wage was set at a level to allow a full-time working single to exit UB II. As the level of 8.50 Euro was set as an average across Germany, regional differences in housing costs can lead to a situation in which even full-time working singles are not able to leave UB II. In particular, in some metropolitan areas, housing costs have increased strongly in recent years. Thus, in economically strong cities such as Munich, Frankfurt or Cologne, a full-time single would need to earn approximately 10 to 12 Euros to avoid claiming additional welfare benefits that are part of Unemployment Benefit II (Herzog-Stein et al., Reference Herzog-Stein, Lübker, Pusch, Schulten and Watt2018).Footnote 1

Risk of poverty

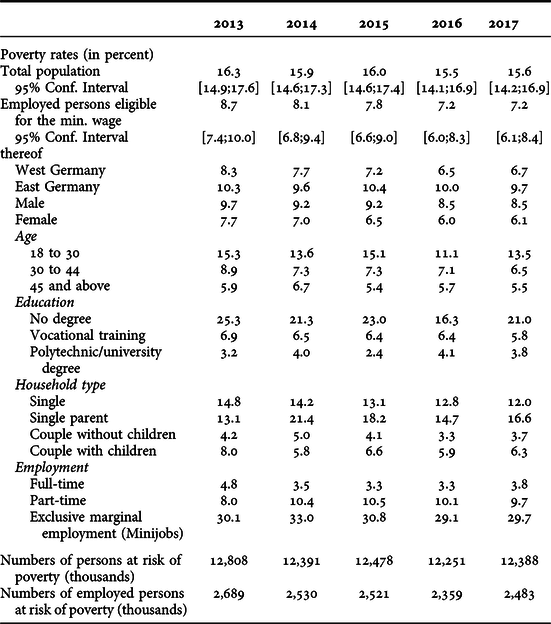

As a second indicator to measure the impact of minimum wages on social policy goals, we will focus on the risk of poverty. A household is considered at risk of poverty if its available income is less than 60 percent of the median income of the total population, both of which are equalized according to the new OECD scale.Footnote 2 According to our own calculations based on the panel dataset “Labour Market and Social Security” (PASS), an annual representative household panel with a sample of approximately 10,000 households, we estimate a poverty threshold of 913 Euro with a median income of 1.522 Euro for 2014.Footnote 3 The descriptive cross-sectional time series shows a slight reduction in the poverty risk rate – the share of individuals living at risk of poverty – for the total population between 2014 and 2017 from 15.9 to 15.6 percent (Table 3).Footnote 4 We do not see a reduction in the number of people at risk of poverty. The poverty rate of the working population fell significantly from 8.1 percent in 2014 to 7.2 percent in 2017. This pattern holds for most subgroups. However, both the poverty rate of the total population and that of the working population declined even before the introduction of the minimum wage in 2015. It therefore remains unclear what contribution the general positive wage trend or the introduction of the minimum wage made to this development.

Table 3. Poverty risk rates of various subgroups

Note: Confidence intervals of subgroups of employed persons eligible for the minimum wage are not displayed for reasons of clarity. The 95 percent confidence intervals of the subgroups show a lower statistical precision and are between 38 percent and 162 percent (Education: Polytechnic/university degree) of the respective displayed value and 81 percent and 119 percent (Western Germany).

Source: PASS Waves 7–11, own calculations.

The only causal effects study available so far is Bruckmeier and Becker (Reference Bruckmeier and Becker2018), who find negative but not robust and significant effects of the minimum wage on poverty rates in Germany. They estimate a difference-in-differences model using employees who earned between 8.50 Euro and 12 Euro in 2014 as a control group. Their analysis refers to 2015 and 2016. For workers in Eastern Germany, the results suggest stronger but still statistically insignificant effects.

The limited impact of the statutory minimum wage on the poverty risk can be explained by a number of factors. First, from approximately 12.4 million people at risk of poverty in 2014, only approximately 2.5 million were in employment. The others were either not of working age or were of working age but actually not working: for instance, because they were unemployed. Thus, only about one out of five individuals at risk of poverty is in a situation in which they can potentially benefit from a higher hourly wage.

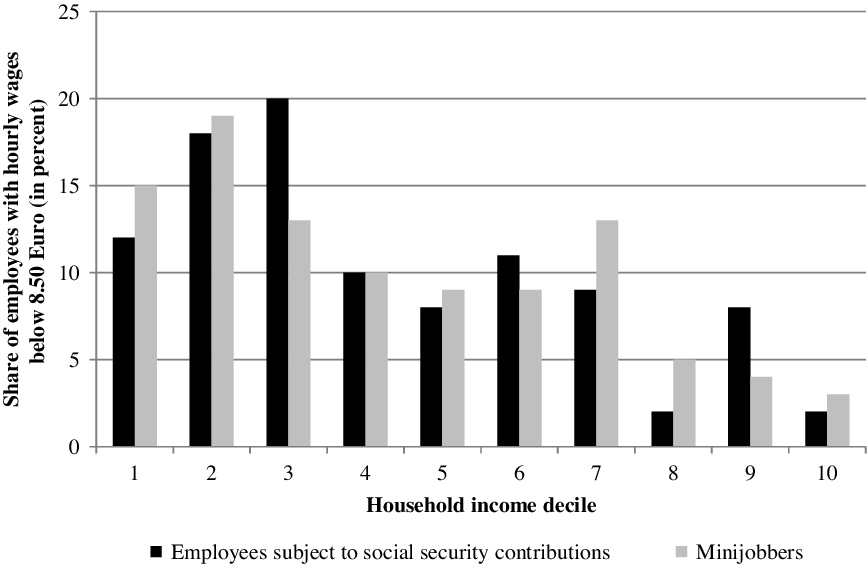

Second, low-wage earners do not necessarily live in households at risk of poverty. According to the PASS data, only approximately 27 percent of employees earning below 8.50 Euro in 2014 lived in households at risk of poverty. Only approximately 12 percent belong to the bottom decile of the income distribution, another 18 percent to the second decile. Although estimated with a lower statistical precision, the share of low-wage earners living in the sixth decile and above accounts for almost one third (Figure 3). The findings from other countries show a similar pattern in the sense that minimum wage earners do not necessarily live in poor households, but often live in households in the upper end of the income distribution (see, for instance, Brewer and de Agostini, Reference Brewer and de Agostini2015, for the United Kingdom, Sabia and Burkhauser, Reference Sabia and Burkhauser2010, for the United States or Leigh, Reference Leigh2007, for Australia).

Figure 3. Distribution of employees with hourly wages below 8.50 Euro by household income deciles, 2014.

Third, the risk of poverty often results from short working hours rather than low hourly wages, a pattern we have also observed with respect to welfare receipt. While full-time employees had a risk of poverty of approximately 3.5 percent in 2014, part-time workers were at 10.4 percent and Minijob workers at 33.0 percent if they did not hold another job.

Discussion and conclusion

Minimum wages are sometimes seen as an instrument to reduce welfare receipt and (in-work) poverty (Lohmann and Marx, Reference Lohmann and Marx2018). Based on the case of Germany, which introduced a general statutory minimum wage in 2015, we have provided empirical evidence on the potential and the limitations of a generally binding wage floor as a social policy instrument. The available evidence thus far suggests that the effects are limited. Neither the number of individuals receiving in-work benefits (“Aufstocker”) nor the poverty risk has declined significantly as a consequence of the minimum wage. The main reasons that we have identified for this outcome are as follows. First, need and poverty often result from low working hours rather than low hourly wages. Second, households often include non-working household members, in particular children, whose needs cannot be covered by a single wage earner, even one working full-time. Third, high and increasing rents in many metropolitan areas crowd out a large portion of the wage gains. Finally, low-wage earners can be found throughout the income distribution, not only at the bottom.

Some caveats need to be kept in mind when interpreting these figures. We can only observe the effects of the statutory minimum wage at a rather moderate level of less than 50 percent of the median wage for full-time employees. Thus, it remains an open question how much the effects would differ in case of a higher level: for instance, 60 percent, as in France’s or the United Kingdom’s target National Living Wage rate. Against the backdrop of the data and patterns observable so far, we believe that the effects would be modest. Even with a higher minimum wage, we would see minimum wage earners living in households across the entire wage distribution and limited working hours as a main reason for requiring public support. In addition, a significantly higher minimum wage might also bring about some downsides, particularly with respect to possible negative employment effects that have mostly been absent so far. Leventi et al. (Reference Leventi, Sutherland and Tasseva2017), for instance, found that minimum wages would need to be raised to very high relative levels, sometimes close to the median wage, to achieve measurable effects on poverty risks. For the United Kingdom, a 90 percent increase in the minimum wage from the baseline of 2013 would result in a decrease in the poverty headcount of −1.8 percentage points and a reduction in the poverty gap of −0.4 percentage points. A 20-percent increase, close to the realized National Minimum Wage level of 60 percent compared to the starting rate of approximately 50 percent of the median wage of a full-time employee, would only have an effect of −0.3 and −0.1 percentage points, respectively.

Another caveat is the current level of compliance with the statutory minimum wage in Germany. Depending on the data source used, approximately two years following its introduction, the extent of non-compliance with the minimum wage was of a relevant magnitude. Based on data from an employer survey by the German Federal Statistical Office, approximately 750,000 jobs paid below the minimum wage in 2016. Based on employee data from the Socio-Economic Panel, the German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) even found approximately 1.8 million employees earning less than 8.50 Euro per hour in 2016 in terms of contractually agreed working hours (see Mindestlohnkommission, 2018 for a comparison of both datasets). Although several methodological issues must be considered when interpreting these non-compliance figures based on surveys (Dütsch et al., Reference Dütsch, Himmelreicher and Ohlert2019; Mindestlohnkommission, 2018), the German Minimum Wage Commission concluded in its Second Report that both databases “find evidence for minimum wage implementation deficits. Even after the introduction and raise of the minimum wage, a substantial number of employees continue to earn less than 8.50 Euros or 8.84 Euros, respectively” (Mindestlohnkommission, 2018: 10).

Even with these caveats in mind, the evidence, not only for Germany but also internationally, shows that the minimum wage does not seem to be a very well-targeted policy instrument to reduce welfare receipt and fight poverty in general and in-work poverty specifically. For the United States, Sabia (Reference Sabia2014) shows that the correlation between low wages and low household income has decreased substantially in recent decades. In 1959, 42 percent of low-wage earners lived in households below the Federal poverty threshold. In 2012, it was only 13 percent. Sabia (Reference Sabia2014) identifies the fundamental change in the composition of workers in households as the key explanation; in particular, from a sole bread-winner model to a model with dual-earner households, resulting from increased female labour market participation.

Raising scepticism about the minimum wage as a social policy tool does not, however, mean that there are no good arguments in favour of minimum wages. Set at a reasonable level, minimum wages seem to be a useful policy instrument to raise wages at the bottom end of the wage distribution without having larger negative effects. They may also have positive effects on a broad range of other indicators used for the measurement of “Social Quality” (Tomlinson et al., Reference Tomlinson, Walker and Foster2016). From a normative point of view, it may also be a legitimate concern to establish a legally binding wage floor that ensures workers earn an acceptable minimum they deserve for their work. It is just important to have in mind what a minimum wage can do and what it cannot. If governments want to reduce in-work poverty, they should recognize that minimum wages are limited in their power to achieve this policy goal. Simulation models have identified other instruments, particularly reforms of the tax and social security system, and direct support such as child benefits, as more effective and efficient instruments (Atkinson et al., Reference Atkinson, Leventi, Nolan, Sutherland and Tasseva2017; Leventi et al., Reference Leventi, Sutherland and Tasseva2017, Reference Leventi, Sutherland and Tasseva2019; Marx et al., Reference Marx, Nolan, Olivera, Atkinson and Bourguignon2015; Marx et al., Reference Marx, Vanhille and Verbist2012). For all these schemes, reaching those who are in need of support and avoiding deadweight effects constitutes a challenge (Immervoll and Pearson, Reference Immervoll and Pearson2009; Marx et al., Reference Marx, Vanhille and Verbist2012). In any such policy mix, minimum wages can serve as an important underpinning instrument. By preventing overly low wage levels at the bottom, wage floors can prevent employers from using in-work benefits to reduce their labour costs. This in turn can reduce overall public expenditure on supporting low-wage workers through in-work benefits. This was certainly a major reason for the United Kingdom’s National Living Wage initiative. When announcing the National Living Wage in his Budget statement in 2015, the then-Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne said taxpayers should not have to help employees stuck with poor wages by contributing to their benefits. On the other hand, to the extent that employers can pass on some of their increasing labour costs in the form of higher prices, it will be customers who carry the burden of higher wages (see Lemos, Reference Lemos2008 for a survey of minimum wage effects on prices).

We are currently observing an increasing interest in higher minimum wages in OECD countries. In the United States, prominent Democrats are pushing for a higher Federal Minimum Wage of up to 15 US Dollars. In Europe, countries such as the United Kingdom, Spain and Belgium aim to achieve a minimum wage level of approximately 60 percent relative to the median wage. There is also a discussion in Germany, particularly among the Social Democratic Party and the leftist Die Linke, about raising the minimum wage to a level of 12 Euros. Against this backdrop, it is important for policy makers to be aware of the potentials and limitations of such a policy.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Arne Baumann, Ralf Himmelreicher, Regina Konle-Seidl and two anonymous referees for their valuable comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors only and do not necessarily represent those of their institutions.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.