Then I saw an angel coming down from heaven, holding in his hand the key to the bottomless pit and a great chain. He seized the dragon, that ancient serpent, who is the Devil and Satan, and bound him for a thousand years, and threw him into the pit, and locked and sealed it over him, so that he would deceive the nations no more, until the thousand years were ended. After that he must be let out for a little while.

Millennial Moments

The end of the first millennium was at hand. For some, so was the end of the world. That Satan would be bound for a thousand years prior to his release and eventual confinement in hell for an eternity was a certainty. That Satan was already bound was a reading of Revelation 20.1–3 (above) that resonated throughout the medieval period. It had the authority of Saint Augustine (354–430). According to Augustine, the binding of Satan had already happened as a result of the victory won over him by the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus the Christ. It was then that he had been thrown into the bottomless pit. The Devil, Augustine declared, ‘is prohibited and restrained from seducing those nations which belong to Christ, but which he formerly seduced or held in subjection’.Footnote 1

According to Augustine, at the end of time and history, Satan would be loosed again. Revelation 13.5 had prophesied that the beast that arose out of the sea would exercise authority for forty-two months. Augustine identified the beast with Satan. The Devil, he wrote, would then ‘rage with the whole force of himself and his angels for three years and six months’.Footnote 2 Then, there would occur the final battle between God and Satan, Christ would come in judgement, and the Devil and his angels, together with the wicked in their resurrected bodies, would be consigned to everlasting punishment in the fires of hell. The time of Satan’s release was also the time of the Antichrist, evil incarnate. As Augustine had put it, ‘Christ will not come to judge quick and dead unless Antichrist, His adversary, first come to seduce those who are dead in soul … then shall Satan be loosed, and by means of that Antichrist shall work with all power in a lying though a wonderful manner.’Footnote 3

Although Augustine was committed to a real end of history at some time or other, he read metaphorically rather than literally the ‘one thousand years’ before Satan was loosed. But many did read it quite literally. Consequently, there was the expectation that Christ would return, Satan would be loosed, and the Antichrist would arise somewhere between the year 979 (a millennium from the then supposed date of Christ’s birth) and the year 1033 (a millennium from the then presumed date of his death and resurrection).

Thus, there were many of the ecclesiastical elite and, no doubt, many among the populace at large who, while taking their basic eschatological or apocalyptic soundings from Augustine, nevertheless saw the end of the world as happening more or less in the immediate future.Footnote 4 In a letter to the kings of France just before the end of the tenth century, Abbo, abbot of Saint-Benoît-sur-Loire (c. 945–1004), recalled that ‘as a youth I heard a sermon preached to the people in the Paris church to the effect that as the number of 1000 years was completed, Antichrist would arrive, and not long after, the Last Judgment would follow’.Footnote 5 He went on to say that he resisted this as vigorously as he could in his preaching, using the books of Revelation and Daniel in rebuttal. But he had also to respond to ‘another error which grew about the End of the World’, and one which had ‘filled almost the entire world’.Footnote 6 This was to the effect that, whenever the commemoration of the Annunciation fell on a Good Friday, the world would end.

It is reasonable to assume that Queen Gerberga, sister of the German ruler Otto I and wife of the French king Louis IV d’Outremer, shared in the apocalyptic anxieties of her subjects. With the battle to be joined between God and the Antichrist in the near future, and with her husband’s kingdom under threat as a result, it was even more reasonable that she should wish to get details on the origin, career, and signs of the Antichrist’s arrival. Thus, somewhere around the year 950, she wrote to Adso, a Benedictine monk (later abbot) of Montier-en-Der in north-eastern France, to learn, as Adso put it, ‘about the wickedness and persecution of the Antichrist, as well as of his power and origin’.Footnote 7

His response to Queen Gerberga was contained in a letter entitled On the Origin and the Time of the Antichrist (De ortu et tempore Antichristi). It was the first biography of the Antichrist or, perhaps better, since it mimicked the genre of ‘the lives of the saints’, it was the first life of an anti-saint.Footnote 8 Adso knew this genre, for he was himself the author of five lives of saints. His originality lay, not so much in any original additions to the Antichrist traditions, but rather in synthesising many of them into a coherent ‘Life of the Antichrist’ from his birth to his death. As Richard K. Emmerson remarks, in giving the numerous discussions of Antichrist the form of the lives of the saints, Adso’s biography contributed ‘to the establishing of the Antichrist tradition as a major part of the religious consciousness of the later Middle Ages’.Footnote 9 The text survives in 9 versions and in 171 manuscripts. Along with the original Latin version, there were numerous translations into vernacular languages. It was, in short, an apocalyptic bestseller.

To Queen Gerberga, at least, Adso’s life of the Antichrist contained a message of hope. For he had declared that the Antichrist would not come so long as the power of the Roman Empire survived, and, at the present, that power resided in the French monarchy, embodied in Gerberga’s husband. For the moment, at least, Gerberga’s anxieties could be calmed.

The Life of the Antichrist

The Antichrist was, according to Adso, quite simply contrary to Christ in all things. He would do everything against Christ. Thus, where Christ came as a humble man, the Antichrist would come as a proud one. He would exalt the wicked and revive the worship of demons in the world. Seeking his own glory, he ‘will call himself Almighty God’.Footnote 10 Many of the ‘ministers of his malice’ have already existed, such as the Greek king Antiochus Epiphanes (c. 215–164 BCE) and the Roman emperors Nero (37–68 CE) and Domitian (51–96 CE). Indeed, there had always been many Antichrists, for anyone ‘who lives contrary to justice and attacks the rule of his [Christ’s] way of life and blasphemes what is good is an Antichrist, the minister of Satan’.Footnote 11

The Antichrist that is to come would be a Jew from the tribe of Dan. Like other men, but unlike Christ who was born of a virgin, he would be born from the union of a man and a woman. Moreover, like other men, but unlike Christ who was born without sin, he would be conceived, generated, and born in sin. At the moment of conception, the Devil would enter his mother’s womb. In the case of Mary the mother of Jesus, the Holy Spirit so entered into her that what was born of her was divine and holy; ‘so too the devil will descend into the Antichrist’s mother, will completely fill her, completely encompass her, completely master her, completely possess her within and without, so that with the devil’s cooperation she will conceive through a man and what will be born from her will be totally wicked, totally evil, totally lost’.Footnote 12 Although not literally the son of the Devil in the way that Christ was the son of God, ‘the fullness of diabolical power and of the whole character of evil will dwell in him in bodily fashion’.Footnote 13

As Christ knew Jerusalem as the best place for him to assume humanity, so too the Devil knew a place most fit for the Antichrist – Babylon, a city that was the root of all evil. However, although he would be born in Babylon, he would be brought up in the cities of Beth-saida and Corozain, the two cities that Christ reproached (Matthew 11.21). He would be reared in all forms of wickedness by magicians, enchanters, diviners, and wizards. Evil spirits would be his instructors and his constant companions.

Eventually, he would arrive in Jerusalem. There, he would circumcise himself and say to the Jews, ‘I am the Christ promised to you who has come to save you, so that I can gather together and defend you.’Footnote 14 The Jews would flock to him, unaware that they were receiving the Antichrist. He would torture and kill all those Christians that did not convert to his cause. He would then erect his throne in the temple, raising up the temple of Solomon to its former state. Kings and princes would be converted to his cause and, through them, their subjects. He would then send messengers and preachers through the whole world. He would also work many prodigies and miracles:

He will make fire come down from earth in a terrifying way, trees suddenly blossom and wither, the sea become stormy and unexpectedly calm. He will make the elements change into differing forms, divert the order and flow of bodies of water, disturb the air with winds and all sorts of commotions, and perform countless other wondrous acts. He will raise the dead.Footnote 15

His power would be so great that even many of the faithful would wonder if he was, in reality, Christ returning.

They would not, however, wonder for very long. For the Antichrist would persecute faithful Christians in three ways. He would corrupt those he could by giving them gold and silver. Those whose faith was beyond such corruption, he would overpower with terror. He would attempt to seduce those that remained with signs and wonders. Those who were still continuing in their faith, unimpressed by his powers, would be tortured and put to death in the sight of all.

Then Adso invoked the authority of the New Testament that there would come a time of tribulation unlike anything experienced before (Matthew 24.21). Every Christian who was discovered would ‘either deny God, or, if he will remain faithful, will perish, whether through sword, or fiery furnace, or serpents or beasts, or through some other kind of torture’.Footnote 16 This tribulation would last throughout the world for some three and a half years. The Antichrist would not, however, come without warning. Before his arrival, the two great prophets, Enoch and Elijah, would be sent into the world. They would defend the faithful against the Antichrist and prepare the elect for battle with three and a half years of preaching and teaching during the time of tribulation. They would convert the Jews to Christianity.

The Antichrist, having taken up arms against Enoch and Elijah, would kill them. Then the judgement of God would come upon the Antichrist. He would be killed by Jesus or by the archangel Michael, albeit through the power of Christ. God would then grant the elect forty days to do penance for having been led astray by the Antichrist. Adso was uncertain how long, after this forty days, it would be before the final judgement. It remained, concluded Adso, ‘in the providence of God who will judge the world in that hour in which for all eternity he predetermined it was to be judged’.Footnote 17

How then did the traditions of the Antichrist that came together in Adso’s On the Origin and the Time of the Antichrist develop over the first millennium of the Common Era?Footnote 18

‘The Antichrist’ Arrives

In the history of Christian thought, Jesus the Christ was goodness in human form. The Antichrist, by contrast, was evil incarnate. And yet the New Testament is remarkably silent about the Antichrist. There are only three passages in the New Testament that refer to the Antichrist, all of which occur in the letters of John. The first appearance of the term ‘Antichrist’ in Christian literature occurs in 1 John 2.18–27. It declares that the Antichrist is both one and many. It declares too that there are already many Antichrists in the world, and that their presence is a sign that the end of the world is at hand: ‘Children, it is the last hour! As you have heard that antichrist is coming, so now many antichrists have come. From this we know that it is the last hour’ (1 John 2.18). There was, in short, an expectation that, before Christ came again, the Antichrist himself would come. The text was a key one in the history of the Antichrist. For it set up the tension between the Antichrist of the future yet to come and the many Antichrists already present.

Who were these many Antichrists? The context of this verse makes it clear that they were, at least, Christians who had left the community to which the author was writing. It is clear too that they had left because they denied that Jesus was the son of God: ‘This is the antichrist, the one who denies the Father and the Son’ (1 John 2.22). We get a further clarification of who these Antichrists were in the second passage that deals with the Antichrist (1 John 4.1–6). Again, the author refers to opponents who are designated this time as ‘false prophets’ (1 John 4.1). These too seem to have denied the divinity of Christ. Every spirit that confesses, we read, that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh is from God, while ‘every spirit that does not confess Jesus is not from God. And this is the spirit of the antichrist of which you have heard that it is coming’ (1 John 4.3). Here, the Antichrist is already present as the spiritual power behind those who deny the truth of the Christian confession. The Antichrist that is to come is ‘in spirit’ already present.

Like the term ‘the Antichrist’, the term ‘false prophet’ is also one that refers to the end times. Thus, for example, in the first of the New Testament gospels, the appearance of false prophets and false Christs was one of the signs of the Last Days (Mark 13.22). And in the last book of the New Testament, the book of Revelation, the second beast of the apocalypse was also identified with ‘the false prophet’. The false prophets of the first letter of John were the deceivers of his second letter. Where in the first letter many false prophets were said to have gone out into the world, here ‘many deceivers’ were said to have gone out. Again, these were unbelievers who did not confess that Jesus Christ had come in the flesh. Any such person, we read, ‘is the deceiver and the antichrist!’ (2 John 7). In sum, the Antichrist of the two letters of John referred to opponents of Christ who foreshadowed the coming of the Antichrist or already embodied his activity as false prophets and deceivers. In each case, they appear to have denied the supernatural origin of Christ. And, in each case, ‘the Antichrist’ functioned to indicate that the end of the world was at hand.

The three letters of John in the New Testament can be probably dated to around the end of the first century.Footnote 19 It is clear, not only from the references to the Antichrist but from the more general theology of the first two letters, that they were written in the general expectation of the end of the age, the passing away of the world, the return of Jesus, and the Day of Judgement. Thus, the legend of the Antichrist was grounded in Christian expectation of the ‘last things’ (death, judgement, heaven, and hell). For its part, within the Christian tradition, the doctrine of the last things (eschatology) was set within the broader framework of a four-act historical drama. It began with God’s creation of the world and the creation of Adam and Eve. It then proceeded, in the second act, to their fall into sin and their expulsion from the Garden of Eden. In the third and central act, God became man and redeemed humankind from the sin of Adam and Eve through the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. In the final act, at the end of history, the Antichrist would arise, Christ would return, Satan and the Antichrist would be defeated, the dead would arise, and God would judge the living and the dead, some for the joys of eternal life in heaven, others for the sufferings of an eternity in hell.

If the first appearance of the term ‘the Antichrist’ was some seventy years after the death of Jesus Christ, some forty or fifty years more were to pass before its next appearance. This was around the middle of the second century in a letter of Polycarp, the bishop of Smyrna (c. 69–c. 155), to the Philippians. As with the community referred to in the letters of John, the Philippian community too was split into theological factions focused around the supernatural origin of Christ. So Polycarp quoted 1 John 4.3 against the dissenters:

‘For whosoever does not confess that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh, is antichrist’; and whosoever does not confess the testimony of the cross, is of the devil; and whosoever perverts the oracles of the Lord to his own lusts, and says that there is neither a resurrection nor a judgement, he is the first-born of Satan.Footnote 20

It was to be another thirty or so years, around 180, before Irenaeus, the bishop of Lyons (c. 130–c. 200), invoked ‘the Antichrist’ again in his Against Heresies. As a youth he had heard Polycarp preach. But unlike Polycarp, for whom ‘Antichrist’ referred only to contemporary heretics and not to an individual to arrive at the end of history, the Antichrist of Irenaeus was clearly an eschatological figure. More importantly, Irenaeus brought together a number of traditions within early Christianity that had been developing since the middle of the first century around Antichrist-like figures that would arise at the end of days. With Irenaeus, as we will later see, the legend of the Antichrist begins.

Eschatology and the Antichrist

Christianity was, from its beginnings, an apocalyptic tradition. Jesus was an eschatological preacher who proclaimed that the last times had begun, that the end of the world was at hand, and that the resurrection of the dead was to be succeeded by God’s judgement upon those who rejected the teachings of Jesus.Footnote 21 The eschatology of Jesus was itself part and parcel of the eschatology of the Judaism within which Jesus’ own teaching was imbedded. A core part of the Jewish eschatology of this time was its expectation of the coming of the Messiah or Christ. The most common belief was that the Messiah would be a descendant of King David, that he would appear at the end of history as a warrior who would defeat the enemies of the people of Israel, and that he would judge the wicked and usher in God’s kingdom over which he would rule.Footnote 22

It is impossible to tell whether Jesus thought of himself as the Messiah who was to come in the Last Days. If he did so think, it was certainly not as the expected warrior-Messiah who would militarily overthrow the foreign rulers from Rome. We can say, however, that he probably did see himself as an eschatological prophet appointed by God and sent to announce the imminent catastrophe about to fall upon the people of Israel. So it is perhaps not surprising that, after his death, his followers came to see him not merely as an eschatological prophet in the style of John the Baptist, but as the eschatological prophet – the Messiah or the Christ of the Last Days.

The writings of the New Testament were composed between the time of the death of Jesus somewhere between 30 and 36 CE and the end of the first century. They were composed in an eschatological setting in the belief that Jesus was the Messiah who was to usher in the end of history. That the end did not come as soon as many early followers of Jesus initially expected entailed the necessity of the development of a narrative of what was to happen between the death and resurrection of Jesus and his return to judge the living and the dead. The Jesus of the first three gospels – Mark, Matthew, and Luke, all of which were written in the second half of the first century – was clearly presented as an eschatological prophet. ‘Truly I tell you,’ declared the Jesus of Mark’s gospel, ‘there are some standing here who will not taste death until they see that the Kingdom of God has come with power’ (Mark 9.1). Each of these three gospels contained parallel teachings by Jesus on eschatological themes (Mark 13.1–37, Matthew 24.1–51, and Luke 21.1–36) that are known as the Little or Synoptic Apocalypse.Footnote 23

The gospel of Mark contains the earliest version of Jesus’ eschatological teachings. According to this, as Jesus was leaving the temple in Jerusalem, one of his disciples expressed his admiration for the size of the stones and buildings. Jesus replied that eventually not one stone would be left standing on another. In short, the temple would be destroyed. The context then shifted to the Mount of Olives, where Jesus delivered an eschatological narrative that connected the destruction of the temple to the end of the world.

Although the Antichrist was not mentioned, there was a number of features of the later Antichrist tradition that appeared in Jesus’ eschatological teachings. The first of these was his warning to beware of those who would later come in the name of Jesus saying, ‘I am he’ (Mark 13.6) and who would lead many astray. Later in the narrative, Jesus warned of those who would say, ‘Look! Here is the Messiah’ or ‘Look! There he is.’ ‘False messiahs [christs] and false prophets will appear’, he declared, ‘and produce signs and omens [wonders/miracles] to lead astray, if possible, the elect’ (Mark 13.22–3).

The second feature of Jesus’ eschatological discourse that was to feature in the later Antichrist tradition was the appearance of the ‘abomination of desolation’ or the ‘desolating sacrilege’:But when you see the desolating sacrilege set up where it ought not to be … then those in Judea must flee to the mountains; the one on the housetop must not go down or enter the house to take anything away; the one in the field must not turn back to get a coat … For in those days there will be suffering such as has not been from the beginning of creation that God created until now, no, and never will be (Mark 13.14–19). This notion of the ‘abomination of desolation’ was drawn from the Old Testament book of Daniel (9.27, 11.31, 12.11) and the first book of the Maccabees (1.54 KJV). In the latter of these (c. 100 BCE), we read that ‘the abomination of desolation’ was set up upon the altar of the temple. In both Daniel and 1 Maccabees, ‘the abomination of desolation’ referred to the profanation of the temple that would precede the end of days. The villain of the piece in both was the Hellenistic king Antiochus IV Epiphanes. In 169 BCE, Antiochus had captured Jerusalem. Two years later, he had banned the practice of the Jewish religion and set up a pagan altar in the temple in Jerusalem.

The book of Daniel (168–164 BCE) presented Antiochus as the final tyrant who would suddenly appear at the end of history. He would be a person of unparalleled wickedness and sinful pride who would consider himself greater than any god and would blaspheme the true God. He would profane and desecrate the temple, and set up the abomination of desolation. He would seduce by deceit and persecute the people for the three and a half years of his reign. This would end suddenly as a result of divine intervention, when there would be ‘a time of anguish, such as has never occurred since nations first came into existence’ (Daniel 12.1). Then would follow a final judgement, when ‘Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life and some to everlasting shame and contempt’ (Daniel 12.2). The final eschatological tyrant will become a core component of the story of the Antichrist, and these features of the final tyrant will all be incorporated into the Antichrist tradition.

The third feature of Jesus’ eschatological discourse in the Little Apocalypse was its general view of the Last Days and of the events that would precede them. There would be wars and rumours of wars, earthquakes, and famines. These would be ‘the beginnings of the birth-pangs’ (Mark 13.8). During this time, Christians would be persecuted, brother would betray brother to death, and fathers their children. Children would rise up against their parents and have them put to death. However, those who endured to the end in the faith would be saved. After all this tribulation, the end would come. There would be cosmological signs: ‘[T]he sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light, and the stars will be falling from heaven, and the powers [supernatural beings] in the heavens will be shaken’ (Mark 13.24–5). Then the Son of Man [the Christ] would come in the clouds with great power and glory. He would send out the angels to collect the elect from the ends of the earth to the ends of heaven. That all said, the date of the end could not be predicted. This uncertainty will become a common feature of the final Antichrist tradition: ‘But about that day or hour, no one knows, neither the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father. Beware, keep alert; for you do not know when the time will come’ (Mark 13.33).

The Man of Lawlessness and the Son of Perdition

In the later Antichrist tradition, the ‘abomination of desolation’ was to become personalised as the Antichrist. That possibility was already present in the New Testament in Paul’s second letter to the Thessalonians.Footnote 24 There it is ‘the man of sin, the son of perdition’ (2 Thessalonians 2.3 KJV) himself who ‘takes his seat in the temple of God declaring himself to be God’ (2 Thessalonians 2.4). ‘The Man of Sin [Lawlessness, άνομίας], the Son of Perdition’ appears in the first two chapters of this letter as part of a more general discussion of Christian eschatology.

It is clear from the first chapter of this letter that the audience to whom Paul was writing were remaining steadfast in their faith in spite of the persecution that they were suffering. The thrust of Paul’s argument was that, in spite of their suffering now, they would be vindicated in the future when Christ returned. Those who persecuted them would then receive their eschatological comeuppance:

[W]hen the Lord Jesus is revealed from heaven with his mighty angels, in flaming fire, inflicting vengeance on those who do not know God and on those who do not obey the gospel of our Lord Jesus. These will suffer the punishment of eternal destruction, separated from the presence of the Lord and from the glory of his might.

Then Christ would be glorified in the midst of his saints and marvelled at by all those who have believed.

That said, Paul was quick to point out in the next chapter that his addressees should not be afraid that this was to happen imminently. Rather, an array of events was to occur before the Day of the Lord began. In the first place, the Man of Sin who was also the Son of Perdition was yet to come. Empowered by Satan, the wickedness of the world would reach its climax in him. There remained the question of why he had not yet come. Although ‘the mystery of lawlessness is already at work’, the ungodly one was currently being held back by a restraining power until his time came.

Who or what this restraining power was would long remain a matter of debate. Paul probably left it deliberately ambiguous. Rhetorically, he was quite simply buying time. His addressees could expect neither the lawlessness to end nor the Son of Perdition to arrive any time soon. That said, when the Son of Perdition did come, then the Lord Jesus would ‘destroy him with the breath of his mouth, annihilating him by the manifestation of his coming’ (2 Thessalonians 2.8). When the Man of Sin, the Son of Perdition who proclaimed himself a god, came, he would deceive the people through signs and wonders before being defeated in a final eschatological battle with Christ. Most significantly, Paul has moved him to centre stage in the unfolding of the final events in the history of the world.

The Dragon and the Beasts

The Antichrist will also come to be identified with the beast(s) in the last book of the New Testament, the book of Revelation (c. 70–c. 95), written by a ‘John of Patmos’ (Revelation 1.9). It is, to say the least, a complex and obtuse book, with features that allowed for a large variety of equally complex and obtuse readings. But with respect to the Antichrist, we can pick up the story in the eleventh chapter of this work. According to this, there would come a time when ‘the nations’ had been tramping over Jerusalem (or the world more generally) for forty-two months, or three and a half years. During this time, there would arise two witnesses – eschatological prophets dressed in sackcloth who called for repentance.

These two prophets would overcome all opposition, for fire comes forth from their mouths and their foes are consumed by it. During the 1,260 days of their prophesying, they would also have authority to shut the sky, so that no rain would fall, along with authority over the waters to turn them into blood and to strike the earth with any kind of plague they desired. The prophets that the author intends to describe are, fairly clearly, Elijah and Moses. For the former had punished King Ahab by withholding rain (1 Kings 17) and the latter was reminiscent of Moses inflicting plagues upon the Egyptians when the Pharaoh refused to allow the people of Israel to leave Egypt.

At the end of their period of prophesying, the first beast would arise: ‘the beast that comes up from the bottomless pit will make war on them and conquer them and kill them, and their dead bodies will lie in the street of the great city that is prophetically called Sodom and Egypt, where also their Lord was crucified’ (Revelation 11.7–8) (see Plate 1). People from different tribes and nations would come and gaze at their dead bodies, gloating over them and celebrating their deaths, refusing to allow them to be placed in a tomb. But then, after three and a half days, the breath of life from God would enter them, and they would stand on their feet. Those who were to see them would be terrified, all the more so when they heard a voice from heaven saying to the resurrected witnesses, ‘Come up here!’ And, while their enemies watched them, they would ascend to heaven in a cloud. At that same moment, there would be a great earthquake, and one-tenth of the city would collapse, and 7,000 people would be killed. The remainder would be terrified. As we will shortly see, although the author of Revelation intended the two witnesses to be read as Elijah and Moses, the Christian eschatological tradition will interpret them as Elijah and Enoch, the two Old Testament worthies who were thought never to have died but to have ascended into heaven.

1 The two witnesses, Enoch and Elijah, killed by the Antichrist.

This is the first time in the book of Revelation that we hear of the beast from the abyss who is introduced only to kill the two witnesses. This beast is not to be heard of again until chapter 13. In the meantime, the author tells us, in chapter 12, the story of the dragon, the woman, and her child. This story is prefaced by the appearance in the heavens of two portents. The first was a woman, in the process of giving birth, ‘clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars’ (Revelation 12.1). The woman was later to be identified with the church, the Virgin Mary, and the divine Wisdom. The moon under her feet and the stars in her crown became part of traditional Marian iconography. Then there appeared a great, red dragon ‘with seven heads and ten horns, and seven diadems on his heads’ (Revelation 12.3). The dragon stood before the woman ready to eat the child as soon as it was born. She gave birth to a male child who was immediately snatched away and taken to God. The woman then fled into the wilderness to a place prepared by God, there to be nurtured for 1,260 days.

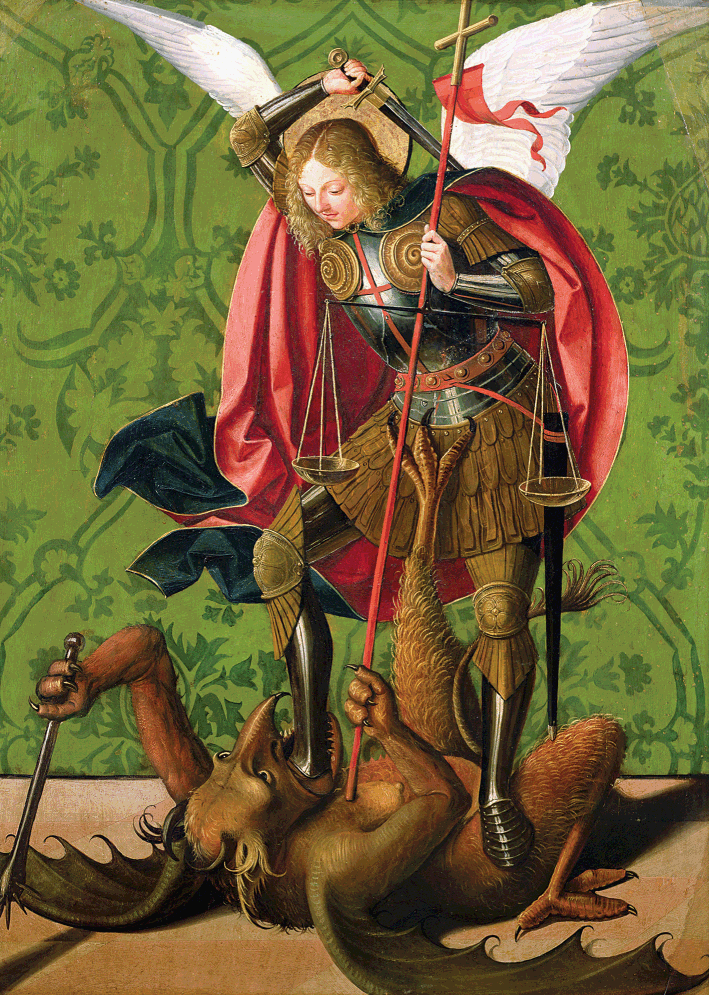

As a result of the dragon’s attempt to consume the child, war broke out in heaven between Michael and his angels and the dragon and his. Although the dragon and his angels fought back, they were defeated and thrown out of heaven (see Plate 2). Then we learn the identity of the dragon. It was he ‘who is called the Devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world’ (Revelation 12.9). Unable to further damage the woman, the dragon went on to make war against the rest of her children. In this, he was assisted by his partners, the two beasts, the one from the sea and the other from the land. They evoke the tradition of Leviathan and Behemoth, the two primeval monsters who live on the sea and land respectively (see Job 40–1).

2 St Michael killing the dragon.

Like the dragon in the previous chapter, the beast that arose from the sea in chapter 13 had ten horns and seven heads. There is little doubt that the author had the four beasts of the Old Testament book of Daniel in mind. In chapter 7 of that work, Daniel told of his vision of four beasts that came up out of the sea – a first that was like a lion and had eagle’s wings, a second that was like a bear with three tusks in its mouth, another like a leopard with four bird-like wings on its back and four heads, and a fourth with great iron teeth and claws of bronze. This last beast was different from the rest, not least because it had ten horns. While Daniel was looking at this fourth beast, a little horn appeared among the other ten that had eyes like human eyes and spoke arrogantly. Three of the earlier horns were plucked up by the roots.

Within the book of Daniel the beasts and the horns served as part of a philosophy of history explaining the inevitability of a succession of empires. The empire of the fourth beast would succeed the previous three until there came ‘an Ancient One’ who put the fourth beast to death and destroyed its body with fire. The ‘Ancient One’ then gave eternal dominion over all things to ‘one like a human being coming with the clouds of heaven’ (Daniel 7.13).

The fourth empire of the ‘little horn’ would succeed the three empires of the uprooted horns. The fourth king would reign for a ‘time, two times, and half a time’ (Daniel 7.25) before he too was consumed and destroyed. The fourth monarchy would be followed by the Kingdom of God – the ‘fifth monarchy’.Footnote 25

In the book of Revelation, the four beasts that arose from the sea in Daniel are merged into one. The beast from the sea in Revelation 13 combined features from each of Daniel’s beasts (Daniel 7). Like the first beast in Daniel, the beast in Revelation arose from the sea. Like the fourth beast in Daniel, the beast that arose from the sea in Revelation had ten horns, although a further little one came up among them (Daniel 7.7–8). Like the second and third beasts in Daniel, the beast from the sea in Revelation was like a leopard and had feet like a bear. And Revelation’s beast from the sea, like the first beast in Daniel, had a mouth like a lion.

The dragon gave the beast from the sea power and authority for forty-two months. For this period, the whole earth followed the beast in amazement and worshipped the dragon. One of its heads was to receive a mortal wound, but it was one from which the beast would recover. Like the little horn in Daniel (Daniel 7.20), the beast was also given a mouth to speak arrogantly and to utter blasphemies against God. It was also allowed to make war on the saints and to conquer them.

Along with the worship of the beast from the sea, its followers are said to bear a mysterious mark, either the name of the beast or the number of its name, which signified who was a follower of the beast. Small or great, rich or poor, free or slave were marked on the right hand or forehead. ‘[L]et anyone with understanding’, we read, ‘calculate the number of the beast, for it is the number of a person. Its number is six hundred sixty-six’ (Revelation 13.18). The beast that arose from the sea was later to be read as a prophecy of the Antichrist that was to come.

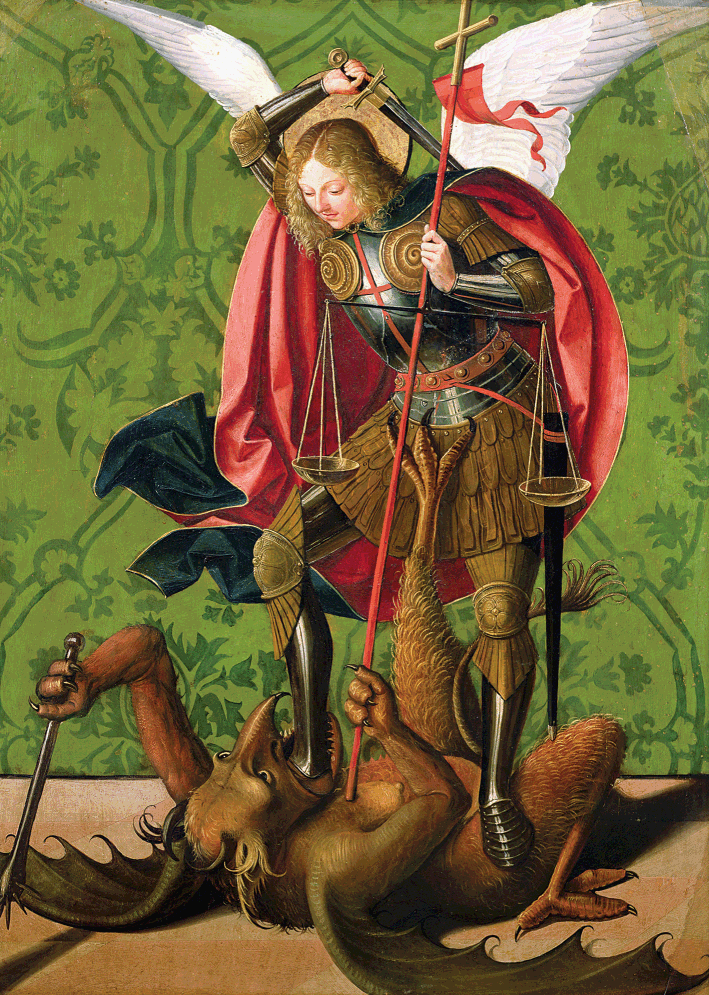

The task of marking the hands or foreheads of the followers of the beast that arose from the sea was assigned to the other beast, the one that arose out of the earth. This beast had two horns like a lamb and it spoke like a dragon. Later in the book of Revelation it was to be called ‘the false prophet’ (Revelation 16.13, 19.20, 20.10). Its primary role was to exercise authority on behalf of the first beast. It forced the earth and its inhabitants to worship the first beast. It performed great signs and wonders, even, like the prophet Elijah, bringing fire down from heaven in the sight of all, thus deceiving the inhabitants of the earth. It was able to animate the image of the beast so that ‘it could even speak, and cause those who would not worship the image of the beast to be killed’ (Revelation 13.15). It was, on occasion, read as an Antichrist succeeding the first beast (see Plate 3).

3 The beast from the sea and the beast from the earth.

The beast from the sea and the beast from the land reappear in chapter 19 of the book of Revelation, where they are players in the final eschatological battle. Then the heavens were said to have opened, and a rider on a white horse – Christ – accompanied by his heavenly armies appeared to judge and to make war. The beast from the sea and the kings of the earth gathered for battle at a place called Harmagedon. Christ destroyed their armies, and the beast was captured, along with the beast from the land – the false prophet. These two ‘were thrown alive into the lake of fire that burns with sulphur’ (Revelation 19.20). The rest were killed with the sword by the rider on the white horse, and their remains eaten by birds.

An angel that came down from heaven seized Satan the dragon, bound him, and threw him into the pit for a thousand years. When the thousand years were ended, Satan was released to gather the nations of the earth – Gog and Magog – together for battle. They surrounded the camp of the saints and the city of Jerusalem. But fire came down from heaven, and they were consumed. Satan was defeated for the second time and thrown into the lake of fire and sulphur, there to rejoin the beast and the false prophet.

In the thousand-year period between the first and second defeats of Satan, those who had died for their faith would reign with Christ. The rest of the dead would come to life at the end of this millennial time, ‘when Death and Hades gave up the dead that were in them, and all were judged according to what they had done’ (Revelation 20.13). Then there was a new heaven, a new earth, and a new Jerusalem, ‘coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband’ (Revelation 21.2).

False Prophets, Messiahs, and a World Deceiver

By the end of the New Testament period, around the beginning of the second century, expectations of the imminent end of the world were no doubt receding. But those traditions that were to make up the story of the Antichrist continued to develop, not least that of the false prophets and the world deceiver who would appear in the Last Days. Thus, for example, The Didache or The Teaching of the Apostles (c. 120) warned its readers to be prepared for the end. Even though no one knew when the Lord would return, its author did not expect it imminently, since there was yet time for his readers to perfect themselves in their faith.

In The Didache, the Last Days were a drama in five acts. In the first, the world was turned upside down. False prophets and seducers would increase, sheep would be turned into wolves, love would turn into hate. Men would hate, persecute, and betray each other. In the second act, ‘the Deceiver of the world’ would appear ‘as though he were the Son of God’.Footnote 26 So, as an imitator of Christ, he would need to present like the son of God. In the tradition of false prophets generally, he would work signs and wonders. Like the beast from the sea in Revelation, the world would be delivered into his hands. And, like the Son of Perdition in 2 Thessalonians, he would do ‘horrible things’, unparalleled in their wickedness since the world began.

Third, when the Deceiver of the world came, all mankind would be tested by fire. Many would perish, but those who were strong in their faith would survive. Fourth, the three signs of the Truth would appear. There would be the sign of the opening of the heavens. This would be followed by the sound of a trumpet. Then there would follow the resurrection of the dead – not of all men, as the tradition would eventually have it, but only of the believers. Finally, as in the Little Apocalypse of the gospel of Matthew (24), Christ would come ‘on the clouds of heaven’. There the story of The Didache abruptly ends. The Deceiver of the world plays no elaborate role in The Didache. He appears there as a sign of the end. There is no mention of a final eschatological battle, or of his defeat. But what we can say is that by the time of The Didache, at its earliest around 120, the notion of a final and future cosmic eschatological opponent was gaining a permanent place within the Christian tradition. The key tension within the history of the Antichrist, that between the eschatological tyrant and the final deceiver, was now in place.

Like The Didache, The Apocalypse of Peter (100–150) drew upon the Little Apocalypse of Matthew 24. It was written as a discourse of the risen Christ to the faithful. Although it is now mostly remembered for its early descriptions of the punishments and joys of the damned and the saved, it played a significant role in the development of the Antichrist tradition through its evocation of an individual false Christ that was to come at the end of the world. The story began with Christ seated on the Mount of Olives, when his disciples came to him and asked what the signs of his return and of the end of the world would be. Christ told them the parable of the fig tree. According to this, when the fig tree had sprouted, the end of the world would come. He then elaborated on what the end of the world would be like. In those days, false Christs would come, claiming ‘I am the Christ who has now come into the world’.

The text now shifts from plural false Christs to a single false Messiah. ‘But this deceiver is not the Christ.’Footnote 27 The false Christ would slay the many who rejected him. Those who died would be reckoned among the good and righteous martyrs who had pleased God in their lives. The two witnesses of the book of Revelation (whom its author intended to be Elijah and Moses) now become, perhaps for the first time, Enoch and Elijah. They were sent to teach the believers that the one who claimed to be Christ was the Deceiver who had to come into the world and do signs and wonders in order to deceive.

It was the Greek theologian Justin (c. 100–c. 165), later beheaded in the reign of the emperor Marcus Aurelius, who continued the tradition of the Man of Sin or Lawlessness that we have already encountered in 2 Thessalonians above. Justin is most remembered for his attempts to demonstrate that Christianity was in alignment with Greek philosophy. But he was also a staunch defender of the developing Christian apocalyptic tradition. His account of the eschatological Man of Sin occurred in a discussion that he had with the Jew Trypho in Ephesus around 135. Justin was clearly referencing a tradition about the eschatological tyrant similar to that in 2 Thessalonians. But Justin’s final enemy, ‘The Man of Sin’ (άνομίας), was read in terms of the book of Daniel. According to this, the one who was coming, the little horn that arose from the head of the fourth beast that had ten horns (Daniel 7.20, 24), would speak blasphemous words against God (Daniel 11.36) and would reign ‘for a time, times, and half a time (Daniel 7.25). The debate within the Dialogue with Trypho concerned the meaning of this last phrase. ‘Thus were the times being fulfilled’, declared Justin,

[A]nd he whom Daniel foretold would reign for a time, times, and a half, is now at the doors, ready to utter bold and blasphemous words against the Most High. In ignorance of how long he will reign, you hold a different opinion, based on your misinterpretation of the word ‘time’ as meaning one hundred years. If this is so, the man of sin must reign at least three hundred and fifty years, computing the holy Daniel’s expression of ‘times’ to mean two times only.Footnote 28

This discussion of the Man of Sin in Justin’s Dialogue with Trypho took place within an account of the ‘two comings’ of Christ – the first when Christ had come and been crucified, the second when he would come again in glory accompanied by his angels. Justin was to discuss the Man of Sin in a later chapter of the Dialogue with Trypho, again in the context of the two comings of Christ. The first coming, Justin reminded his readers, was when Christ suffered and was crucified without glory or honour; the second was when he would come from the heavens in glory. Again referencing the book of Daniel (11.36), that would be the time when ‘the man of apostasy who utters extraordinary things against the Most High, will boldly attempt to perpetrate unlawful deeds on earth against us Christians’.Footnote 29

Justin, like the author of the book of Revelation, was no doubt drawing upon a tradition within early Christianity of a blasphemous eschatological tyrant who would reign for a period of time shortly before Christ came in glory. This was a tradition that was reliant on the book of Daniel. But Justin was also drawing on an early Christian tradition in which the evil tyrant who was to come and persecute those of the faith was known as ‘the Man of Sin’, ‘the Son of Perdition’, and ‘the Man of Apostasy’.

The Eschatological Tyrant

Like Justin’s Dialogue with Trypho, the Epistle of Barnabas (70–150) looked to the book of Daniel for its understanding of the final opponent. The eschatological section in this work takes the form of a moral exhortation to Christians to be as perfect as possible when the end comes. Above all, they have to beware ‘the final trap’. This had to do with the appearance of the eschatological tyrant described in Danielic terms as the evil king or little horn that had sprung from the head of the fourth beast who would humble three of the ten kings or great horns in the last times (Daniel 7.19–21, 24). His readers were warned even now to beware of ‘the Black One’ (Satan) and to flee all vanity, to hate evil deeds, and to seek the common good. Eventually, we read, the Lord would judge the world, and each would receive according to his deeds. Finally, Christians were exhorted never to become complacent about their sins ‘lest the Prince of evil [Satan] gain power over us and cast us out from the Kingdom of God’.Footnote 30 Satan was clearly active in the present times, but, down the line, the eschatological tyrant of Daniel would appear.

The Epistle of Barnabas gives us an early indication of just when the tyrant might appear. It contains a very early reference to the tradition that the time from the creation of the world until its end would be 6,000 years:

Concerning the Sabbath He Speaks at the beginning of Creation: ‘And God made in six days the work of His hands, and on the seventh day He ended, and rested on it and sanctified it.’ Note, children, what ‘He ended in six days’ means. It means this: that the Lord will make an end of everything in six thousand years, for a day with Him means a thousand years … So, then, children, in six days everything will be ended. ‘And he rested on the seventh day.’ This means: when His Son will come and destroy the time of the lawless one and judge the godless, and change the sun and the moon and the stars – then He shall indeed rest on the seventh day.Footnote 31

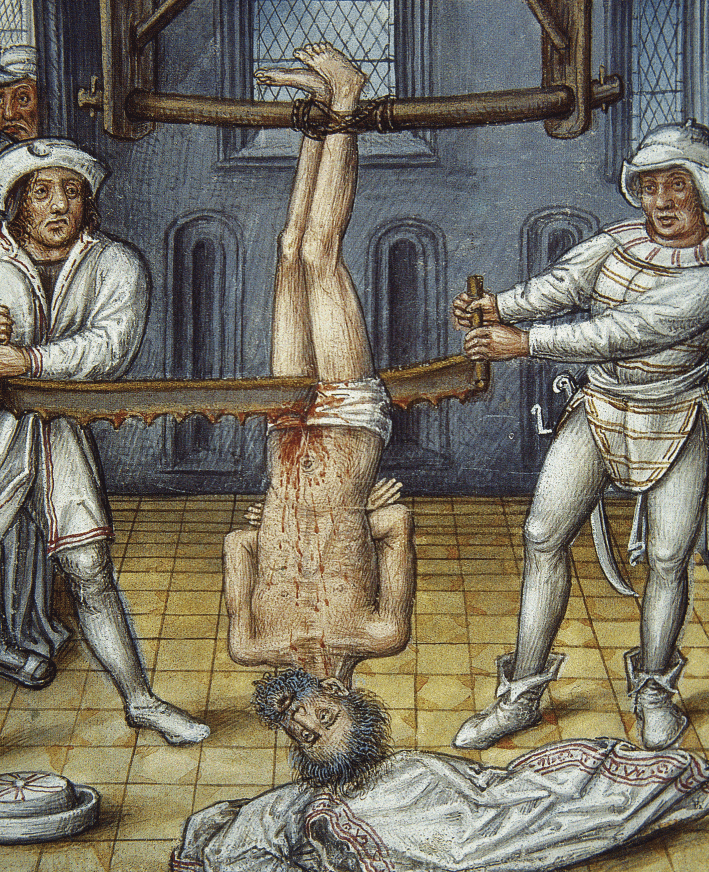

It is reasonably clear that the Epistle of Barnabas did not make a strong distinction between Satan as a supernatural figure engaged both in the present and the future and the future eschatological tyrant, from the Danielic tradition, as a human being. The boundaries were similarly blurred in a Christian text known as the Testament of Hezekiah (early second century) that forms part (3.13–4.22) of a larger work of both Jewish and Christian origin known as The Ascension of Isaiah. In this story, the false prophet Belkira brought charges of sedition and treason against Isaiah. King Manasseh had Isaiah arrested. Isaiah was imprisoned and then executed by being sawn in two with a wood saw (see Plate 4). At the time, King Manasseh was under the influence of the demonic figure called Beliar who was especially angry at Isaiah for having had a vision of Beliar (Sammael, Satan) descending from the vault of heaven and having prophesied the coming of Christ as a man, his earthly ministry, crucifixion, resurrection, ascension, and second coming.

4 The martyrdom of Isaiah.

For the author of the Testament of Hezekiah, his own times were deeply corrupt. As the end of the world approached, the disciples would abandon the teaching of Christ, Christian leaders would love office, money, and worldly things, and lack wisdom. This was the world of corruption, strife, and dissent into which Beliar, the great angel, the king of this world, would ultimately descend. He would have power over the sun and the moon. He would come down ‘from his firmament in the form of a man, a king of iniquity, a murderer of his mother – this is the king of this world – and will persecute the plant which the twelve apostles of the Beloved will have planted’.Footnote 32 He would be both tyrant and deceiver, for he would act and speak like Christ, saying, ‘I am the Lord, and before me there was no one.’Footnote 33 Many would believe that he was Christ come again. Most Christians would follow him. He would show his miraculous power in every city and district and, like the ‘abomination of desolation’ in Revelation, would set up his image everywhere. He would rule for three years, seven months, and twenty-two days. The few Christians who remained faithful would await the coming of their Beloved. This was Daniel’s ‘time, times and half a time’ revisited but computed differently.

The Testament of Hezekiah then presented a quite distinctive eschatology. It is in fact a complex interweaving of two early Christian traditions about the afterlife. The first of these was that the dead would go to Abraham’s bosom (heaven) or Hades (hell) directly after death, the other, that life after death would not commence until Christ comes in judgement at the end of the world.Footnote 34 According to the Testament of Hezekiah, there would be no final eschatological battle. Rather, when Christ did come with his angels and saints, he would simply drag Beliar and his hosts into Gehenna.

There would also be no final judgement for both the living and the dead, the faithful and the faithless. Rather, in the Testament of Hezekiah, the faithful who have died were already in heaven, and those still alive would ascend into heaven before the final judgement. So the saints already in heaven would bring heavenly robes for those on the earth. All of them would then ascend into heaven, the faithful leaving their bodies behind on the earth. Only then would a judgement occur, and only upon the wicked. The heavens and the earth and everything in it would be reproved by an angry Christ. The wicked would then be raised from the dead. Christ would cause fire to come forth from him and consume all the impious.

Thus, by the early second century, we can say that the belief that, before Christ finally comes in judgement, there would arise a powerful eschatological opponent who would mercilessly persecute the Christian faithful was firmly in place. He would be a false prophet and a false messiah. He would be both an eschatological tyrant and a world deceiver, the Man of Sin and the Son of Perdition. He would be Daniel’s abomination of desolation and the little horn of the fourth beast, along with one or more of Revelation’s beasts. He would be the demonic Beliar, both identical with and distinct from Satan. He was a creature not so much of the present as of the (not too distant) future.

Ironically, it was the failure of the end of the world to arrive that made possible, and perhaps necessary, an historical narrative of the interim period between the ascension of Jesus and his return to judge the living and the dead. The task was to explain the failure of the end to come as expected as part of the unfolding of God’s overall plan for the Last Days. The opposition that the followers of Jesus were encountering made necessary an account of the end times that included powerful opponents within and without the faith, together with the expectation of a final eschatological enemy. By the end of the second century, as we will see in the next chapter, these different traditions of the final eschatological opponent were to come together in the figure of the Antichrist.