The presence and purpose of the Damascus escape narrative (2 Cor 11.32–3) within Paul's broader boasting in weakness throughout 11.23b–33 have puzzled scholars. One solution, first suggested by Edwin Judge and developed by Victor Furnish, is that Paul casts the story as a parody of the corona muralis, a wall-shaped crown given to the first soldier to ascend an enemy city wall and so breach their fortifications.Footnote 1 On this reading, Paul portrays himself as the first one down the wall, his cowardly flight from danger providing an example of weakness. Although many scholars have accepted this proposal,Footnote 2 the corona muralis parallel has only been suggested on the basis of a handful of examples and has never been substantially developed.

The aim of this article is therefore to provide the most definitive answer possible to the question of whether Paul alludes to the corona muralis in relating his escape from Damascus. We begin with some preliminary remarks on establishing the likelihood of allusions, before turning to discussion of the corona muralis itself. Employing an extensive range of ancient references to the corona muralis, along with scholarship on Roman siege warfare and military awards, we address the issue of how familiar Paul and the Corinthians were likely to have been with the corona muralis and lay out the language and imagery most commonly associated with this award. These observations inform our reading of the escape from Damascus, where we will evaluate the strength of any evidence that might signal an allusion to the corona muralis.

1. Establishing the Likelihood of Allusions

The issue of detecting allusions has been treated most frequently in New Testament studies with respect to intertextuality. A brief look at this discussion will inform our approach to finding parallels more generally. Since Samuel Sandmel's influential article criticising ‘parallelomania’, a haphazard approach to detecting intertextual allusions,Footnote 3 scholars have attempted to find criteria for establishing intertextuality.Footnote 4 No consensus has been reached, and despite their appearance of objectivity, criteria approaches depend much on the interpreter's impressions.Footnote 5 More significantly for our purposes, criteria approaches have been far more widely used for establishing allusions than providing checks and balances against unwarranted parallels.Footnote 6

Steve Smith's recent proposal for approaching intertextuality provides guidelines for either establishing or rejecting purported allusions. His approach is grounded in relevance theory, a framework for understanding human communication developed by Dan Sperber and Deidre Wilson.Footnote 7 Relevance theory purports that the comprehension of human communication is a process of seeking optimal relevance.Footnote 8 Relevance itself has two components: ‘contextual effect’Footnote 9 and ‘mental effort’. The most relevant interpretation of an utterance is that which produces the most significant impact on the interpreter (contextual effect) while requiring the smallest possible mental effort.Footnote 10

Relevance theory predicts that, because the aim is optimal relevance, a hearer will stop searching for meaning once they have reached the most accessible relevant interpretation.Footnote 11 Searching for extraneous layers of meaning in a text therefore overreaches the limits of normal human communication, requiring unnecessary ‘mental effort’ for diminishing ‘contextual effects’. This means that for an allusion to be a plausible interpretation, there must not be a more accessible interpretation that satisfies expectations of relevance. It must be the most optimally relevant interpretation.Footnote 12

Smith also provides guidelines describing how allusions can achieve relevance. Because the reader requires prompting to search for meaning outside the immediate context, some sort of signalling is necessary. Such signals can range from explicit quotative formulae, such as ‘it is written’, to more implicit connections between the text and the context alluded to.Footnote 13 More implicitly signalled allusions run the risk of being ignored in favour of relevant interpretations closer to the immediate context.Footnote 14 Such allusions require parallels strong enough, and that provide enough interpretative payoff, to direct readers to them.Footnote 15

Although much more could be said about relevance theory and allusions, the principles overviewed here will enable us to assess the likelihood that an allusion to the corona muralis in 2 Cor 11.30–3 would have been the relevant interpretation for Paul's audience. We will assess what signals may be present in the text and whether their strength is sufficient to direct the reader away from the immediate context to imagery associated with the corona muralis.

2. The corona muralis

Before moving to Second Corinthians itself, we will evaluate how accessible an allusion to the corona muralis would have been to Paul's audience and describe what contextual information was normally associated with this award.Footnote 16 We begin by determining the likelihood that the Corinthians would have been familiar with the meaning of the corona muralis as a military award for being the first soldier to surmount the enemy wall. This establishes a rough baseline probability for the parallel. We then lay out the imagery typically associated with the corona muralis, including the sort of language most frequently used in reference to it along with a brief discussion of the military logistics behind how the award would have been won. This information will guide our assessment of what signals might constitute an allusion to the corona muralis.

2.1 The Corinthians’ Familiarity with the corona muralis

It has been taken for granted that Paul and the Corinthians would have known what the corona muralis was and how it was won. Judge claims that ‘everyone in antiquity would have known that the finest military award for valour was the Corona muralis’.Footnote 17 Furnish adds that there was a statue of the goddess Fortuna wearing a corona muralis in Corinth,Footnote 18 while Ben Witherington suggests that ‘Paul's converts would have known of the convention [of the corona muralis] and perhaps even the statue’.Footnote 19

There are two potential misconceptions here that need to be clarified. First, Judge's statement that the corona muralis was the ‘finest military award’ is incorrect. Several gold or silver crowns were awarded for feats of military daring, including ‘the corona vallaris to the first over a rampart,Footnote [20] and the corona classica (rostrata or navalis) to the first onto an enemy ship’, as well as the more general golden crown (corona aurea).Footnote 21 The most prestigious crown of the imperial period was the corona civica, ‘awarded to a soldier who saved the life of a Roman citizen and held the spot where the rescue had been effected’.Footnote 22 The corona muralis was therefore only one of several significant military awards.

Second, although Furnish does not equate the crown of Fortuna in Corinth with the corona muralis as a military award, it is important to emphasise that a crown decorated with the motif of a wall has a different meaning when it adorns a goddess. Fortuna wears a corona muralis because she is a patroness and protrectress of Corinth,Footnote 23 not because she conquers walled cities. The following passage, taken from Lucretius’ first-century bce poem De rerum natura (2.606–9), illustrates the association between a corona muralis-wearing goddess (here Cybele) and the protection of the city:Footnote 24

And they have surrounded the top of her head with a mural crown, because embattled in excellent positions she sustains cities; which emblem now adorns the divine Mother's image as she is carried over the great earth in awful state. (Rouse and Smith, LCL)

This distinction is significant because it means that knowledge of the corona muralis as the adornment of a goddess and knowledge of the corona muralis as a military award are not mutually reinforcing. An ancient person could see Fortuna's statue in Corinth and understand the significance of her crown without ever knowing how the corona muralis functioned as a military award in the Roman army.

We may now address whether Paul and the Corinthians would have known of the corona muralis as an award for being the first soldier to surmount a city wall. This issue is complicated by the fact that the criteria for awarding several military awards underwent a process of transition throughout the first century that changed their meanings.

Under the Roman Republic, crowns were generally awarded on the basis of merit for the specific action represented by the award. At this time, the corona muralis was given out for being the first to surmount the enemy wall.Footnote 25 Imperial Rome however developed a more complex, ranked-based system for the distribution of awards.Footnote 26 Under this system, the coronae (other than the corona civica) ‘lost all connection with the deeds which they were originally designed to commemorate’ and became stock awards given in different combinations depending on the rank of the recipient.Footnote 27

This transition had occurred by ‘the third quarter of the first century [ce]’.Footnote 28 The corona muralis specifically was still, albeit infrequently, awarded on the basis of merit during the reign of Augustus (see Suetonius, Aug. 25.3), but inscriptional evidence indicates that it had become a rank-based award by the time of Gaius – more than ten years before Paul wrote First Corinthians.Footnote 29 For the Corinthians to connect the corona muralis with taking an enemy wall, they would therefore need not only have known of the corona muralis as a military award, but also what it used to signify.

Furnish cites second-century historian Gellius to demonstrate that the original meaning of the corona muralis as an award for ‘the man who is first to mount to the wall’ (Gel. 5.6.16, Rolfe, LCL) was still known in the second century;Footnote 30 the implication is that this earlier meaning would have therefore been familiar to Paul's congregation in the mid-first century.Footnote 31 This line of reasoning overstates the significance of the evidence. Gellius does know the original awarding criteria for the corona muralis, as do other historians writing after Paul – largely from the late-first to early-second century.Footnote 32 But these writers are historians writing on military affairs. It is unrealistic to expect that the average person would have been as familiar with the former meaning of a seldom-awarded military decoration as professional historians.Footnote 33 We must therefore conclude that the consensus assumption that Paul and his audience would have definitely known of the corona muralis as a military award for being the first soldier to ascend the enemy wall is incorrect. It is plausible that Paul and/or any number of his congregants would not have been aware of this meaning of the corona muralis, and it is also possible that they would have. This analysis does not rule out the possibility of an allusion to the corona muralis in 2 Cor 11.32–3 a priori, but it does reduce its overall probability.

2.2 Imagery Typically Associated with the corona muralis

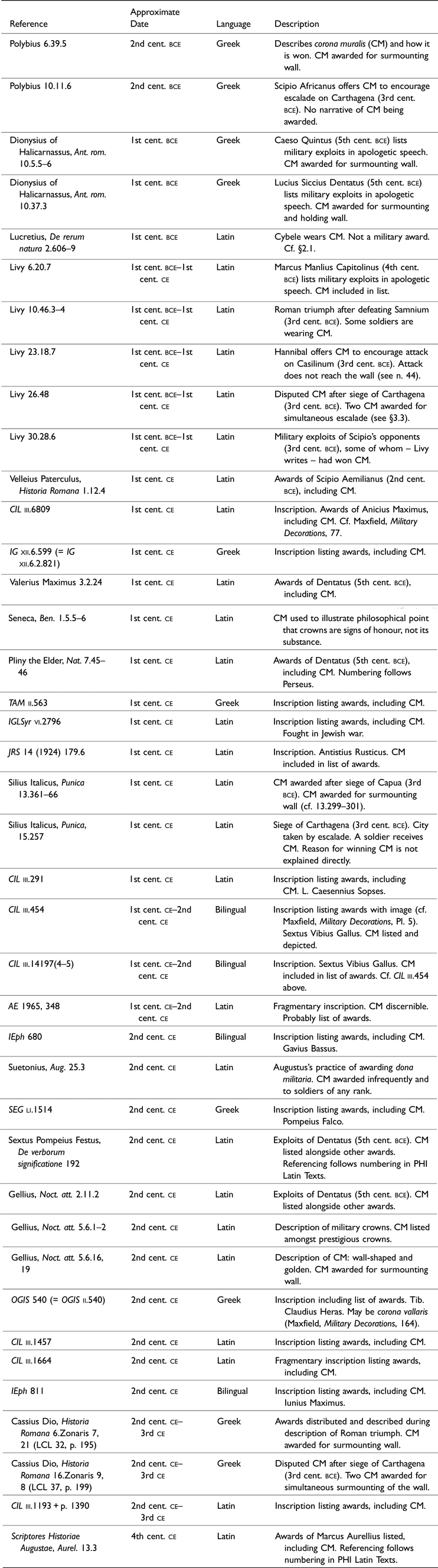

Our dataset consists of thirty-nine references to the corona muralis as a military award drawn from literary sources and inscriptions (ten in Greek, twenty-five in Latin and four bilingual; for a full listing, see Appendix).Footnote 34 Across all texts, references to the terms ‘crown’ (στέφανος, corona) and ‘wall’ (τɛίχος,Footnote 35 τɛιχικός,Footnote 36 πυργωτός,Footnote 37 muralis) are ubiquitous. Making further observations about the language typically associated with the corona muralis requires us to take chronology into account (cf. section 2.1). Seventeen of our references are relevant to the original awarding criteria for the corona muralis (six Greek, eleven Latin),Footnote 38 where it was given to the first soldier to mount the enemy wall. All other references collected depict the corona muralis as a standard, rank-based, award, or at least do not contain any evidence of its earlier meaning.

References to the earlier meaning of the corona muralis occur in the works of historians spanning a timeframe from the second century bce to the second century ce. Here being ‘the first one to mount the wall’ (τɛίχους τις πρῶτος ἐπέβη, Cassius Dio, Historia Romana 6.Zonaris 7, 21)Footnote 39 is significant, with language of being first (πρῶτος)Footnote 40 and of ascending (ἐπιβαίνω, ἀναβαίνω + ἐπί)Footnote 41 occurring frequently. Gold is also significant (Polybius 6.39.5; 10.11.6; Livy 23.18.7; Aulus Gellius, Noct. att. 5.6.19), as this is the material the crown was traditionally made of.Footnote 42 The value of the corona muralis is expressed using language of honour and valour.Footnote 43 Further expressing its worth, both Polybius and Livy depict the prospect of winning the corona muralis as an effective means of encouraging acts of bravery (Polybius 6.39.1–5; 10.11.6; Livy 23.18.7).

Outlining the military logistics of how the corona muralis was originally won can provide further insight into the sort of imagery an ancient person would have associated with it. Only one narrative clearly describes an attack after which the corona muralis was awarded.Footnote 44 Here a ladder assault (escalade) is used to surmount the walls of New Carthage (Polybius 10.12–14; Livy 26.44.5–46.4). Escalade featured in Roman siege warfare throughout the period in which the corona muralis was awarded for actually scaling walls.Footnote 45 While it seems plausible that a soldier reaching the wall by means of a siege tower would have also qualified for the corona muralis, we have no direct evidence of the corona muralis being awarded for this or any other way of reaching the top of a wall.Footnote 46

The majority of references to the corona muralis as a rank-based award come from inscriptions dating as early as Gaius’ reign (CIL iii.6809), but most are from the late-first century or the second century ce. These inscriptions describe their subject's military career and list their military awards. With the technical term for military awards being dona militaria, lists of awards are often prefaced with the phrase donis (militaribus) donato.Footnote 47 As in the earlier period, language of honour and valour remains associated with the corona muralis as a rank-based award (ἀνδρɛία,Footnote 48 ἀρɛτή,Footnote 49 τιμή/τιμάωFootnote 50). But language related to the actions required to win the crown in the earlier period – i.e. being first up the wall – is no longer in play.

3. The corona muralis and the Escape from Damascus

We now assess arguments made in previous scholarship for an allusion to the corona muralis in 2 Cor 11.30–3. We begin by addressing the military imagery employed in 10.3–5, as several scholars have argued that this strengthens the likelihood of a corona muralis parallel. We then discuss each piece of evidence relevant to 2 Cor 11.30–3, following verse order. This enables us to approach the text as the Corinthians would have first heard it and evaluate where in the reading the audience's attention may have been drawn to the corona muralis.

3.1 The Relevance of 2 Cor 10.3–5 to the corona muralis

3 Ἐν σαρκὶ γὰρ πɛριπατοῦντɛς οὐ κατὰ σάρκα στρατɛυόμɛθα, 4 τὰ γὰρ ὅπλα τῆς στρατɛίας ἡμῶν οὐ σαρκικὰ ἀλλὰ δυνατὰ τῷ θɛῷ πρὸς καθαίρɛσιν ὀχυρωμάτων, λογισμοὺς καθαιροῦντɛς 5 καὶ πᾶν ὕψωμα ἐπαιρόμɛνον κατὰ τῆς γνώσɛως τοῦ θɛοῦ, καὶ αἰχμαλωτίζοντɛς πᾶν νόημα ɛἰς τὴν ὑπακοὴν τοῦ Χριστοῦ

3 Indeed, we live as human beings, but we do not wage war according to human standards; 4 for the weapons of our warfare are not merely human, but they have divine power to destroy strongholds. We destroy arguments 5 and every proud obstacle raised up against the knowledge of God, and we take every thought captive to obey Christ. (NRSV)

Scholars have argued that the military imagery in 2 Cor 10.3–5 makes a parallel with the corona muralis in 11.32–3 more salient.Footnote 51 In this section we will address the extent to which this military imagery might draw the audience's mind either to the corona muralis or to situations associated therewith, before going on to discuss its relevance to 11.30–3 in the next section.

To describe Paul as portraying himself ‘as a conquering military leader’Footnote 52 in 2 Cor 10.3–5 would be to overstate the force of this military imagery. Paul portrays himself primarily as a person divinely empowered to argue effectively and make thoughts obedient to Christ. Martial language simply forms the metaphor employed to make this point. This is of course not the same as boasting of actual combat experience, which many of Paul's contemporaries could do. Paul makes it clear that he is not a literal soldier fighting with literal weapons (τὰ γὰρ ὅπλα τῆς στρατɛίας ἡμῶν οὐ σαρκικὰ, 10.4). The military language in 10.3–5 is therefore disconnected from Paul's self-portrayal by a layer of abstraction. It emphasises the central point, namely, ‘Paul is divinely empowered’, but is not itself the thrust of Paul's argument. Because the image Paul-as-soldier is not the relevant interpretation of 10.3–5, it is unlikely that this image would persist long in the mind of his audience and would be readily recalled later without clear signalling.

Granted that Paul's military language in 10.3–5 is a metaphor for something else, what images does this language evoke and how do they relate to the corona muralis? Paul refers to soldiering (στρατɛυόμɛθα, 10.3; τῆς στρατɛίας, 10.4), weapons (ὅπλα, 10.4), destroying fortresses (καθαίρɛσιν ὀχυρωμάτων, 10.4) and taking captives (αἰχμαλωτίζοντɛς, 10.5). στρατɛυ-language and ὅπλα are both too general to evoke the corona muralis specifically.

Taken together, destroying fortresses and taking captives could evoke images related to siege warfare,Footnote 53 but their connection to the corona muralis goes no further than this. Taking captives is a military operation unrelated to the corona muralis. As discussed in section 2.2, at the time when the corona muralis was awarded on the basis of mounting the enemy wall, this was normally accomplished through escalade. The assault leading to the awarding of the corona muralis therefore would leave the wall intact. A ladder is not a weapon with ‘divine power to destroy strongholds’ (ὅπλα … δυνατὰ τῷ θɛῷ πρὸς καθαίρɛσιν ὀχυρωμάτων, 10.4 NRSV).

Martin asserts that Paul's reference to destroying fortresses (πρὸς καθαίρɛσιν ὀχυρωμάτων, 10.4) alludes to Prov 21.22 LXX: ‘A wise person attacked strong citiesFootnote 54 and demolished the strongholds in which the impious trusted’ (πόλɛις ὀχυρὰς ἐπέβη σοφὸς καὶ καθɛῖλɛν τὸ ὀχύρωμα ἐφ᾽ ᾧ ἐπɛποίθɛισαν οἱ ἀσɛβɛῖς, NETS).Footnote 55 He further argues that Paul connects his escape from Damascus to 2 Cor 10.4–5, Prov 21.22 and the corona muralis, with Paul ‘deliberately setting off his life of weakness against the exploits of the wise’.Footnote 56 Two caveats are necessary here. First, Paul's military language in 2 Cor 10.4–5 obtains relevance through emphasising his divine empowerment. It does so by employing imagery of power and strength drawn from siege warfare and military language more generally. Because this imagery is readily accessible to Paul's audience,Footnote 57 it satisfies expectations of relevance. With this expectation met, the Corinthians have no reason to search for a further allusion to make sense of the text (cf. section 1).Footnote 58

Second, Martin is arguing for three separate allusions – 2 Cor 10.4–5, Prov 21.22 and the corona muralis – as underlying the narrative of Paul's escape from Damascus. We will address possible allusions in 2 Cor 10.30–3 in more detail in the following sections. Here it will suffice to say that relevance theory would rightly suggest that it is very unlikely for recourse to three distinct allusions to be the optimal way to make meaning of a text.

The military imagery in 2 Cor 10.4–5 is a means of emphasising God's empowerment of Paul – power he is ready to use against those who oppose him (10.6). This imagery may call siege warfare to mind, but not the corona muralis specifically. Clear signalling would be necessary to relate 11.30–3 to 10.4–5, and to connect either to the corona muralis.

3.2 Paul's Language of Weakness (2 Cor 11.30) and the Relevance of 2 Cor 10.3–5 to 11.30–3

Εἰ καυχᾶσθαι δɛῖ, τὰ τῆς ἀσθɛνɛίας μου καυχήσομαι.

If I must boast, I will boast of the things that show my weakness. (NRSV)

The distance between 2 Cor 10.3–5 and 11.30–3 is itself not insignificant. Between these two passages Paul discusses the tone of his letters (10.7–11), comparison and boasting (10.12–18), reasons for his foolish boasting (11.1–6), the financial practices of his ministry (11.7–11), his opponents (11.12–15), further reasons for his foolish boasting (11.16–21), his background (11.22) and his hardships (11.23–9). When Paul's audience hears the narrative of his escape from Damascus, an interval of several minutes has passed since Paul used military language as a metaphor in 10.3–5, and several topic changes have occurred. If Paul means to have his audience recall 10.3–5 as the relevant background for the escape from Damascus, he will need a clear signal.

Paul does refer his audience back to preceding discourse in 2 Cor 11.30, but not to military imagery. He has been describing his hardships and sufferings in the immediately foregoing passage (11.23–9) and has just mentioned having feelings of weakness (τίς ἀσθɛνɛῖ, καὶ οὐκ ἀσθɛνῶ; 11.29). When Paul says that he ‘will boast of the things that show [his] weaknesses’ (τὰ τῆς ἀσθɛνɛίας μου καυχήσομαι, NRSV), he draws his audience's attention to the weaknesses he has just expressed rather than to previous language signifying strength (10.3–5). 11.30 makes Paul's weaknesses the relevant background for understanding the narrative of his escape from Damascus.Footnote 59 There is no reason for his audience to search for a different interpretive framework.

3.3 Paul's Oath: 2 Cor 11.31

ὁ θɛὸς καὶ πατὴρ τοῦ κυρίου Ἰησοῦ οἶδɛν, ὁ ὢν ɛὐλογητὸς ɛἰς τοὺς αἰῶνας, ὅτι οὐ ψɛύδομαι.

The God and Father of the Lord Jesus (blessed be he forever!) knows that I do not lie. (NRSV)

Judge writes, ‘[the corona muralis] was only awarded after strict verification of the claim: hence, no doubt, Paul's oath in support of his claim’.Footnote 60 Judge does not cite any sources in support of this assertion, and indeed there is no evidence that the verification process for awarding the corona muralis was normally exceptional. Of the thirty-nine references to be corona muralis assessed in this study, only one mentions the taking of oaths. We explore this passage now briefly.

Writing largely during the reign of Augustus, the Roman historian Livy describes Scipio Africanus’ siege of New Carthage (Livy 26.42–7). The assault on the city includes two attacks by escalade, the second of which is successful (26.44.5–46.3). After taking the city, Scipio praises his soldiers (26.48.5) and requests that the one who first ascended the wall come forward and claim the corona muralis (profiteretur qui se dignum eo duceret dono, 26.48.5). After two men declare themselves, a dispute breaks out, pitting the military factions associated with each claimant against each other (26.48.6–7). Judges are appointed to settle the dispute without violence, but the proceedings soon become dishonest and still threaten to turn violent (26.48.8–11). ‘The legionaries stood on one side, the marines on the other, ready to swear by all the gods to what they wanted to be true rather than what they knew to be true, and to taint with perjury not just their own persons but their military standards … and the sanctity of their oath of allegiance’ (26.48.12, Yardley, LCL). Scipio judiciously resolves the situation by awarding the corona muralis to both parties for mounting the wall at the same time (26.48.13).Footnote 61

This narrative does not imply that the winner of the Corona muralis was usually contentious. Valerie Maxfield does state that the process depicted in this scene, where claimants for an award are asked to come forward, would have been standard for exploit-based crowns such as the corona muralis and corona vallaris.Footnote 62 But Livy's narrative is our only evidence of such a dispute having occurred and it seems likely that Livy considered this episode worth recording for its being an exceptional rather than common situation. While the corona muralis may have occasionally been contested in such a way as to require witnesses and oath-taking, it would be a considerable over-reading of the evidence to suggest that it would have been in any way synonymous with oaths.

Paul's oath in 2 Cor 11.31 would therefore neither draw his audience's attention to the corona muralis nor does it suggest that Paul had such a parallel in mind.

3.4 Downward Motion from the Wall: 2 Cor 11.32–3

32 ἐν Δαμασκῷ ὁ ἐθνάρχης Ἁρέτα τοῦ βασιλέως ἐφρούρɛι τὴν πόλιν Δαμασκηνῶν πιάσαι μɛ, 33 καὶ διὰ θυρίδος ἐν σαργάνῃ ἐχαλάσθην διὰ τοῦ τɛίχους καὶ ἐξέφυγον τὰς χɛῖρας αὐτοῦ.

32 In Damascus, the governor under King Aretas guarded the city of Damascus in order to seize me, 33 but I was let down in a basket through a window in the wall, and escaped from his hands. (NRSV)

Here we investigate whether any elements of Paul's narrative of his escape from Damascus could allude to the corona muralis. With no signals in the foregoing text pointing to the corona muralis as the relevant background for interpreting 2 Cor 11.32–3, the Corinthians would require clear cues in the narrative itself to make such an allusion salient.

Most obviously, Paul uses the word τɛίχος ‘wall’ (2 Cor 11.33). This is one of two words for ‘wall’ typically used in connection with the corona muralis (cf. section 2.2). But walls are a commonplace feature of ancient cities, with many distinct images and actions associated therewith. In the absence of the term ‘crown’ (στέφανος), the Corinthians would have required further signals to draw their minds to the corona muralis.

Scholars have seen this signal in the manner of Paul's descent from the wall. Ivar Vegge describes Paul's motion down the wall as a parodic inversion of the soldier's assent of the wall in winning the corona muralis.Footnote 63 Witherington writes, ‘Paul is saying that while the typical Roman hero is first up the wall, he is first down the wall!’Footnote 64

This latter point overstates the evidence. Paul makes no mention of being first.Footnote 65 This absence becomes more significant when we note that most authors who refer to the earlier meaning of the corona muralis, when it was awarded for surmounting the enemy wall, make reference to being first (πρῶτος, primus).Footnote 66

In terms of motion, the ascent of the soldier who wins the corona muralis is most often described with ἐπιβαίνω (four occurrences, see section 2.2), and also with ἀναβαίνω + ἐπί (Polybius 6.39.5; 10.11.6). ἐχαλάσθην (2 Cor 11.33) does not (parodically) invert this motion in a manner that could signal an allusion to the corona muralis. Technically, being lowered by another party can be considered the opposite of ascending under one's own power. But there is no linguistic connection between ἐχαλάσθην and ἐπιβαίνω/ἀναβαίνω + ἐπί such that the former might remind Paul's audience of the latter.Footnote 67 Likewise, motion through (διὰ) a window is not meaningfully related to the act of surmounting (ἐπί) a wall.

To illustrate this disconnect, we set Paul's statement beside the first-century bce historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus’ narrative of a speech by Lucius Siccius Dentatus, in which Dentatus extols his military achievements (see Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Ant. rom. 10.36–40):

As to rewards for valour (ἀριστɛῖα), I have brought out of those contests fourteen civic crowns, bestowed upon me by those I saved in battle, three mural crowns for having been the first to mount the enemy's walls and hold them (τρɛῖς δὲ [στɛφάνους] πολιορκητικοὺς πρῶτος ἐπιβὰς πολɛμίων τɛίχɛσι καὶ κατασχών), and eight others … (Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Ant. rom.10.37.3, Henderson, LCL)Footnote 68

In Damascus, the governor under King Aretas guarded the city of Damascus in order to seize me, but I was let down in a basket through a window in the wall (καὶ διὰ θυρίδος ἐν σαργάνῃ ἐχαλάσθην διὰ τοῦ τɛίχους), and escaped from his hands. (2 Cor 11.32–3, NRSV)

Scholars have described 2 Cor 11.32–3 as parodying the ‘military boast’ represented by the corona muralis.Footnote 69 But when we compare Paul with the only extant first-person narrative of a soldier boasting about winning the corona muralis, it becomes clear that these two accounts are disparate both in terms of the language used and the situations described. Paul is not making parodic reference to something like what we see in Dionysius of Halicarnassus, or any other extant reference to the corona muralis. He is simply telling an unrelated story.

But could Paul be alluding to the actions and images associated with a soldier in the process of qualifying for the corona muralis, rather than to the ways in which the corona muralis was usually described? As discussed in section 2.2, we have direct evidence that the corona muralis was awarded following attack by escalade. The soldier worthy of the corona muralis boldly climbs a ladder to be the first to reach the top of the wall in assaulting a besieged city (cf. Livy 26.44.5–9). They may be under fire from missiles thrown from the wall (Polybius 10.13.9; Livy 26.44.6–9; 26.45.1), and are in danger of falling or being cast down (Polybius 10.13.6–9; Livy 26.45.3–4). If things go badly, injury can occur (Livy 26.44.9; 26.45.5; 26.46.1), and doubtless also death.

The language Paul uses to describe his escape from Damascus has no relationship to an attack by escalade leading to the awarding of the corona muralis. Windows (θυρίδɛς) in walls are not related to escalade, where soldiers are trying to reach the top of the wall. Mention of a woven basket (cf. LSJ s.v. σαργάνη) would not signal an allusion to a ladder. Being secretly lowered down a wall in a basket presents an image unrelated to a soldier climbing a ladder. Paul's descent of the wall is also dissimilar to the inverse of the soldier who wins the corona muralis: the unlucky soldier who falls.Footnote 70

It should not be surprising that Paul's escape from Damascus has no meaningful connection to the corona muralis. It is, after all, a narrative about escaping (καὶ ἐξέφυγον τὰς χɛῖρας αὐτοῦ, 2 Cor 11.33), rather than a narrative about siege warfare.

4. Conclusions

An allusion to the corona muralis in 2 Cor 11.32–3 has been often suggested but never really demonstrated. A thorough examination of the evidence enables us to close this question with confidence: it is exceedingly unlikely that Paul alludes to the corona muralis in narrating his escape from Damascus.

Analysis of the historical data problematises the consensus assumption that Paul and his audience would have been familiar with the corona muralis as a military award for being the first soldier to scale the enemy wall. The meaning of a wall-shaped crown differed depending on time period and context. By Paul's day, the corona muralis was no longer awarded for scaling walls, and familiarity with its earlier significance would have required a certain degree of specialised historical knowledge that not everyone would have had access to.

Insights from relevance theory guided our assessment of the evidence from Second Corinthians (10.3–5; 11.30–3). The principle that constructing meaning from communication is a process of seeking the most easily accessible, relevant interpretation led us to look for specific signals within the text that would draw the audience's attention to the language and imagery associated with the corona muralis. No such signals were found. Paul does not connect the Damascus narrative to previous military imagery (10.3–5), but explicitly ties it to the weaknesses he has just been describing (11.30). Neither Paul's oath (11.31) nor his descent from the wall (11.32–3) bears any meaningful resemblance to the ways in which the corona muralis was described or won such that they could signal an allusion thereto. Paul's escape from Damascus is not an inversion or parody of the corona muralis, it is an unrelated narrative.

Scholarship must therefore look elsewhere to determine how Paul's escape from Damascus would have obtained relevance and fulfilled the expectation of boasting in weakness created in 2 Cor 11.30. I believe there are two possibilities here worthy of further consideration. First, several scholars have suggested that the means of Paul's escape, i.e. being lowered in a basket, leaves him in a position of weakness.Footnote 71 While this would be sufficient to establish the narrative as an example of weakness, more research is needed to determine precisely why and to what extent this manner of descent would be considered undignified or embarrassing.Footnote 72

A second suggestion requiring further exploration is that Paul's escape is in some way analogous to other escape narratives, such as Josh 2.15, which tend to reflect well on the escapee.Footnote 73 Profitable work remains to be done on such escape narratives and their reception across ancient Jewish and Greek texts. It is not difficult to imagine Paul's flight from Damascus being taken as an example of his wit, courage and of God's provision, as this is precisely how the author of Acts spins the story (Acts 9.23–5).

These two options may appear contradictory, but they are not mutually exclusive. Paul could be presenting a narrative in a self-deprecating manner that he knows his audience will look on more favourably. This would be close to what colloquial English refers to as a ‘humblebrag’ and has an analogy in Paul's subsequent narrative of his vision (2 Cor 12.1–6). Here Paul describes a vision that he considers worth boasting about (12.1, 5), but in a way that enables him to, technically, not boast about it (12.5–6, 9). Paul may therefore be treading a fine line between boasting in weakness and straightforward self-promotion in both the escape and vision narratives.

Multiple possibilities exist for understanding Paul's escape from Damascus that are far more plausible than an allusion to the corona muralis. However, as illustrated by the history of the corona muralis hypothesis itself, all of these require further research and verification before being accepted in scholarship.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Appendix: Table of Corona muralis References