1. Introduction

South Korea's persistent enmity towards its erstwhile colonizer Japan has been a compelling topic of East Asian international relations scholarship for decades. Frustration is particularly palpable among American analysts of alliance politics, who have waited with increasing impatience for the mutual security concerns and economic ties of these two wealthy Asian democracies to outweigh their historical grievances. Among international relations (IR) theorists, the relationship confounds classical realists, whose models predict the two powers balancing against rising China, liberals, who predict economic common interests and institutional frameworks should compel them to reconcile, and constructivists, who expect common culture and norms to mitigate conflicts. Post-colonial reconciliation scholarship has long treated the South Korea–Japan relationship as an anomaly, as other colonial dyads of that period (Britain–India, France–Vietnam, and even Japan–Taiwan) have achieved generally amicable relations with far less in the way of formal apologies or reparations.

When faced with an anomaly, it often helps to investigate what else is anomalous about the case. In this regard, it seems significant that the South Korean political landscape today is far more progressive and pluralist than its geopolitical position and history would lead one to expect. Given that it emerged from one of the most virulently anti-communist dictatorships of the Cold War period, in a society still bearing the scars of a brief but brutal communist invasion and facing continuous North Korean provocations, any opposition movement politically left of the ruling right-wing dictatorship faced an uphill battle against severe anti-communism. In such circumstances, I argue that the only way for a left-wing opposition party to survive and level the political playing field was by having an alternative bogeyman, a totem capable of arousing as much visceral anger and existential dread as North Korea. In monster movie terms, Korean leftists needed a Japanese Godzilla to match up against the North Korean Pulgasari.Footnote 1

In this article I take a domestic politics approach to an IR puzzle, arguing that the evolution of South Korea's modern democracy offers important clues to the persistent political salience of Japan historical issues that are often overlooked. The fact that the long-ruling conservative partyFootnote 2 historically contained many alleged chinil (친일; lit. “pro-Japan,” typically refers to colonial-era collaborators, their descendants, and anyone excessively defending/admiring Japan) and had long suppressed critical reexaminations of colonial history during the dictatorship period set the stage for a cathartic explosion of anti-Japanese and anti-collaborator actions in the democratic period from 1987 onward. This included demolishing still-standing colonial edifices (Han Reference Han2013, Sîntionean Reference Sîntionean2017), setting up institutions to correct the historical record on colonial collaboration and Korean War-era atrocities (Suh Reference Suh2010), and challenging the legitimacy of the 1965 Japan–South Korea normalization treaty that had been a central pillar of the developmental state headed by President Park Chung-hee (Lee Reference Lee2021). Such measures won political capital for the ascendant liberal wing with a public that were otherwise conditioned to be leery of leftist platforms for labor organization, wealth redistribution, and inter-Korean reconciliation. Still, Korea's left and center-left parties have continuously struggled against accusations of communist sympathies and being soft on North Korea. Even now, as North Korea remains a threat and an unreliable partner in so many ill-fated pro-engagement initiatives, anti-Japanism remains an indispensable weapon of Korea's left wing to counter conservative red-baiting.

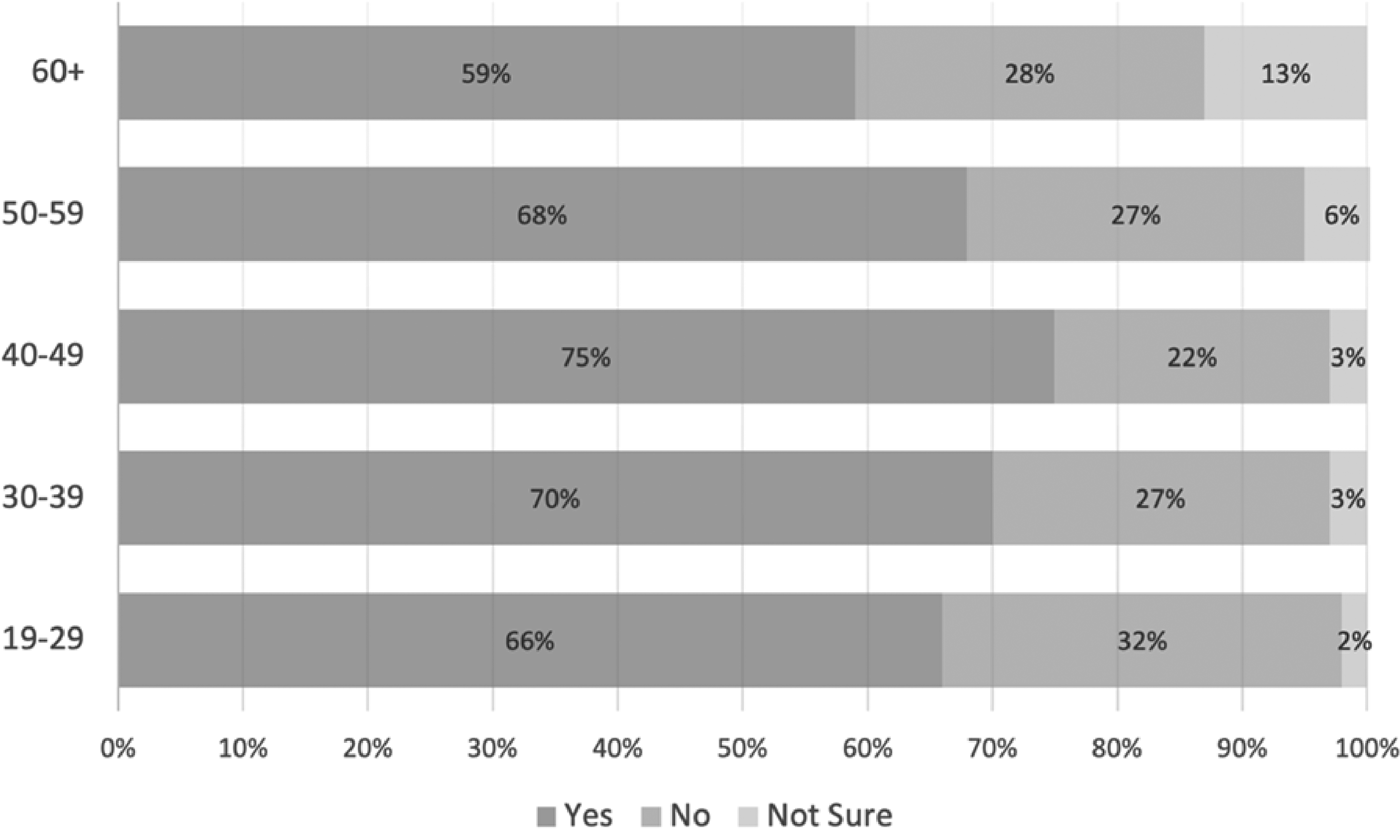

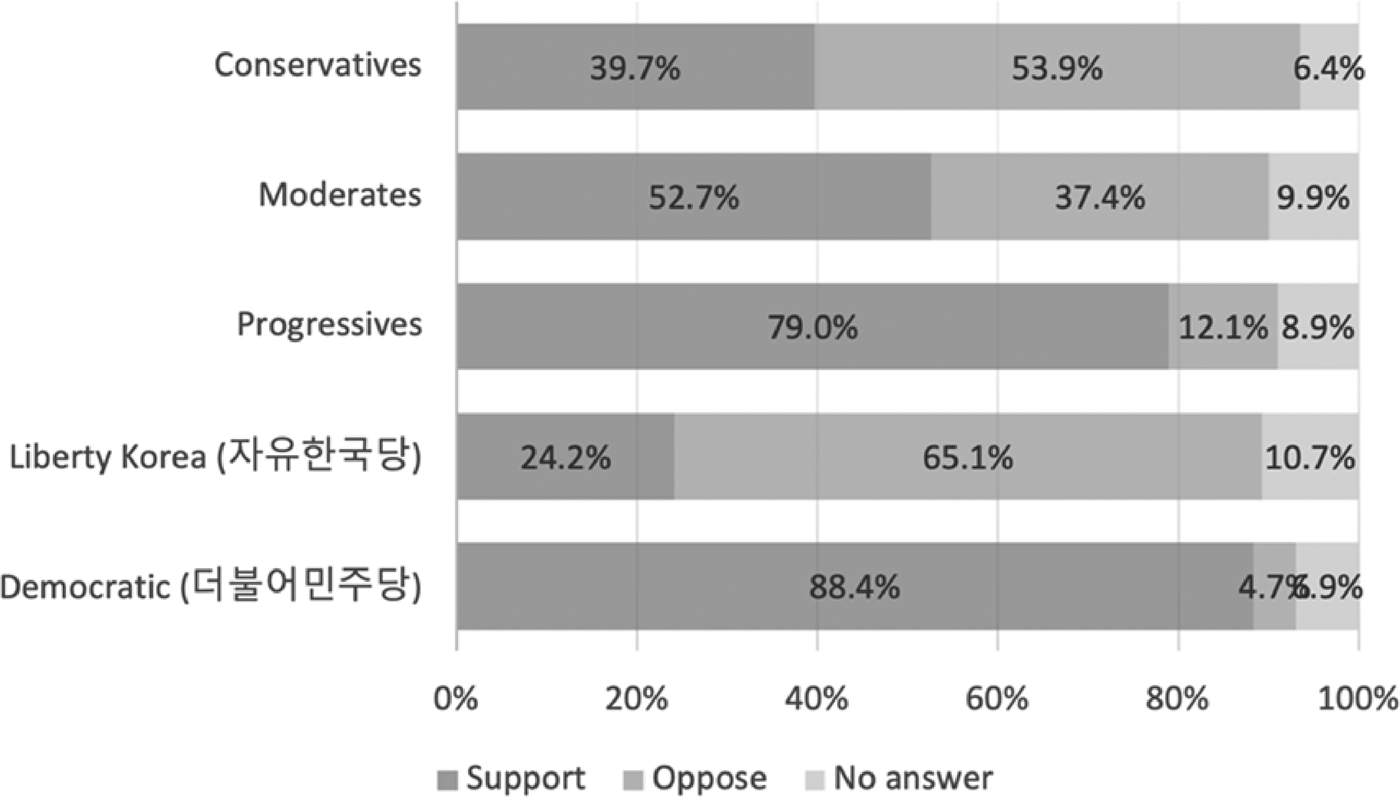

Once we understand South Korea's partisan political dynamic as an equilibrium between anti-communist right and anti-Japanese left, another enduring puzzle of modern Korean politics comes untangled: why (relatively) younger generations remain highly mobilized on Japan historical issues. While other reconciliation case studies show that relations generally improve among younger generations as memories fade of the actual events, South Korea seems exceptional. This is less puzzling once we understand that the pursuit of postcolonial justice is strongly associated with Korea's left and center-left political parties, which tend to have a more youthful base than the right. For instance, while there was broad public support for the Japanese product boycott in summer 2019 (see Section 5), Figure 1 shows a clear partisan divide, with self-identified conservatives and independents showing more reluctance than supporters of the (progressive) Justice and (liberal) Democratic parties. By age cohort (Figure 2), the same poll reveals the bow-shaped pattern that is representative of generational attitudes: young and elderly people trend more positively toward Japan, while those in the middle (particularly the progressive-leaning “586 generation,” now in their fifties) trend more negatively.

Figure 1. Respondents Intending to Participate in 2019 Japanese Product Boycott (% by Party Preference) (Gallup Korea 2019, 12)

Figure 2. Respondents Intending to Participate in 2019 Japanese Product Boycott (% by Age Cohort) (Gallup Korea 2019, 12)

The following section presents a critical review of existing alternative explanations for the persistent South Korea–Japan tensions. Section 3 then presents an alternative framework built upon securitization theory and proposes a set of tools for examining how, in ideologically polarized settings, competing parties seek to identify their adversaries with external threats as a tactic for mobilizing votes and support. Section 4 provides historical context to establish how the two external antagonisms have come to be split along partisan lines. The empirical Section 5 examines four episodes over the last decade when dueling political rhetoric over these twin antagonisms came to the fore during periods of heightened partisan competition and shows how conservative anti-communist rhetoric often came into direct competition with liberal rhetoric against Japan. Section 6 concludes.

2. Scope and Literature Review

This article does not aim to exempt Japan from responsibility for its part in the bilateral relationship. Key figures in Japanese politics and media continue to make unhelpful statements sullying the sincerity of past apologies, support textbooks that whitewash its atrocities, and hold the perpetrators of colonial rule in high esteem. However, none of this behavior is particularly atypical among former imperial powers. Rather, it is the South Korean side's persistently high mobilization on Japan issues and its increasing enmity over time that make this dyad unusual and thus worthy of focused analysis. An analysis of Japanese political dynamics toward Korea is beyond the scope of this article.

Where this case appears in the inter-state apologies literature, Japan's apologies are usually compared with its World War II ally Germany (Lind Reference Lind2011) or its World War II enemy the US (Dudden Reference Dudden2008). This tends to put the analytical focus on war crimes rather than colonial abuses and sets the standard for comparing apologies accordingly. Few scholars have sought to compare Japan–Korea relations alongside European post-colonial dyads. Even among former Japanese colonies, South Korea appears anomalous when compared to Japan's more successful reconciliations with Taiwan, Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, and the Philippines. Only China and North Korea show greater resistance to reconciliation, and both have obvious geopolitical motives for maintaining tensions with Japan.

Among Western IR scholars, chiding comparisons to Cold War Western Europe are popular. Stephen Walt, comparing the case unfavorably to European examples of balancing alliances, argues that “these two states are letting national pride cloud their thinking in a most unproductive way” (Walt Reference Walt2012). Veteran Korea analyst Aidan Foster-Carter chides, “It's long past time for South Korea and Japan to finally bury the past and focus on building the future … Europe offers a precedent. After 1945, France and Germany managed to transcend a history of enmity—three wars in 70 years—and build what became the EU. Sadly, East Asia's elites lack that vision or courage, each preferring to hunker in their own bunker” (Foster-Carter Reference Foster-Carter2017). Here, again, we may quibble over the validity of comparing wartime adversaries and colonial dyads. But beyond that, such remarks demonstrate the classic IR problem of ignoring internal political divisions and portraying a unified national response to an external stimulus. Over six decades after Waltz (Reference Waltz1959) ignited the “second image” debate on the domestic origins of foreign policy, the IR field continues to struggle with a monolithic view of state agency that occludes the complex interactions of competing domestic interests.

Within the realist tradition, one popular explanation for Japan–South Korea discord is US alliance bandwagoning. Analyzing bilateral dynamics from 1965 to 1998, Cha (Reference Cha1999) showed that in periods when the American defense commitment to the region is weak, South Korea exhibits significantly less contention with Japan. However, the most recent nadir in bilateral relations (the “whitelist” trade crisis of summer 2019) coincided with a moment when the US defense commitment was arguably at its weakest point in 40 years (the US president was rhapsodizing about his good relationship with the North Korean leader and threatening to withdraw troops unless Seoul increased its annual payment five-fold to $5 billion). As most of Cha's analysis covered the pre-democratic Cold War period, it largely predated the South Korean domestic partisan dynamics presented here.

Kelly (Reference Kelly2015) brings North Korea and domestic politics into the analytical picture, but in a very different sense than this article does. He hypothesizes that “North Korea so successfully manipulates Korean nationalist discourse that South Korea cannot define itself against North Korea in the same way West Germany did against East Germany. So South Korea uses a third party against which to prove its nationalist bona fides in its national legitimacy competition with the North.” Nationalist rivalry is an indisputable feature of inter-Korean relations. Yet it is hard to blame North Korean nationalist manipulation for the magnitude of anti-Japan sentiment in the South, particularly when its propaganda materials are still banned and anti-communism remains such a potent force. Furthermore, what was missing in the West German case was not a communist rival attempting to manipulate nationalist discourse, but a despised former colonizer to divert public ire away from its principal communist enemy.

Some regional IR scholars, noting that South Korea–Japan relations seemed to begin their downward trajectory around the end of the Cold War, have theorized that some sort of geopolitical realignment or altered threat perceptions are to blame (Park Reference Park2008). But post-Cold War realignment hypotheses fall flat when confronted with the parallel case of Taiwan, which existed under Japanese colonial rule for even longer than Korea and was subjected to the same policies of cultural assimilation and war mobilization. Today both Taiwan and South Korea face similar realist expectations to align with US allies against China, and both have ongoing territorial disputes with Japan over small islands of dubious historical ownership. Yet Taiwan's rhetoric and behavior toward Japan is markedly warmer than South Korea's.

Among area specialists, the prevailing explanations for this divergence rely on comparative historical perceptions. Lai (Reference Lai2020), comparing rhetoric on Japan–Korea and Japan–Taiwan territorial disputes, argues that the difference is rooted in pre-colonial history: “Before Japanese annexation in 1910, Korea had established the institutions of sovereignty and enjoyed a long period of independence. Thus, South Korea is more likely to perceive Japan as a threat to its security. Taiwan, as one of China's southeastern provinces, did not have such independence before colonization by Japan” (Lai Reference Lai2020, 590–591). Though this characterization is broadly valid, it seems insufficient to account for the vastly different public sentiments toward Japan in modern-day South Korea and Taiwan. Furthermore, Korea was hardly the first sovereign, independent nation to be colonized and later liberated (cf. Vietnam, Myanmar, India).

Lai interestingly mentions that Taiwan's attitudes toward Japan diverge along party lines, though in the opposite direction from the Korean partisan divide: while the center-left DPP generally takes the position of standing with fellow democracy Japan against communist China, the center-right KMT in pursuit of its “one China” policy often takes the position of standing with China against Japan. Yet Lai is dismissive of any such partisan divergence in South Korea, writing “Unlike in Taiwan, where political parties failed to reach a consensus on Japan policy, the Dokdo issue united Koreans to safeguard the nation's sovereignty despite their other political differences … Such a united front presents a strong contrast to the lack of consensus in Taiwanese society.” (Lai Reference Lai2020, 597). As supporting evidence, Lai presents one rather dated but fiery quote from a Roh Mu-hyŏn administration official but no quotes from conservatives, and then cites a short 2011 article written for a US think tank (Park and Chubb Reference Park and Chubb2011).

The Park and Chubb article points to then-recent actions by the conservative Lee Myung-bak administration to block a delegation of Japanese lawmakers from visiting Dokdo, concluding that “This issue [Dokdo] brings together all Koreans, no matter what their political inclination—a rare occurrence in a country which is itself deeply ideologically and politically divided … Any concessions on the part of Korean lawmakers are unlikely and would be akin to political suicide” (Park and Chubb Reference Park and Chubb2011). The last part is certainly true, but by examining the rhetoric, this article shows that the liberal side drives the discourse on Japan issues, while the old guard right-wing leaders tend to avoid the subject or retaliate with anti-communism to counteract opposition criticism. Section 5.i will examine the special case of Lee's Dokdo maneuver in greater detail.

This dynamic of right-wing groups stoking public anger against North Korea while left-wing groups focus on Japan is nothing new to scholars of South Korean domestic politics (Doucette and Koo Reference Doucette and Koo2016, Yi, Phillips, and Lee Reference Yi, Phillips and Lee2019, Glosserman and Snyder Reference Glosserman and Snyder2015). Yet these scholars have not concerned themselves with the broader postcolonial reconciliation literature enough to apply this knowledge to the puzzle of South Korea's enduring enmity toward Japan in comparison to other post-colonial dyads, or to suggest that South Korea's unique position at the vanguard of anti-communism might be the key to unlocking that puzzle.

Glosserman and Snyder (Reference Glosserman and Snyder2015) posit that bilateral relations are shaped by “‘national identity,’ as revealed by values, beliefs and resulting social systems” (Reference Glosserman and Snyder2015, 20), using polls and interviews to show how identity shapes policy preferences in both Japan and South Korea. Their analysis does touch on South Korean partisan divisions, noting that “The primary divisions over identity and nationalism have historically occurred between conservatives and progressives” and that such divisions emerged more clearly after democratization (Glosserman and Snyder Reference Glosserman and Snyder2015, 63). They observe an identity conflict between Korean progressives’ “classic ethnic nationalist impulse for unity of the race” and conservatives’ prioritization of “an ideology that also embraces freedom and democracy” (Glosserman and Snyder Reference Glosserman and Snyder2015, 65), without acknowledging how historically eccentric it is to see progressives championing the former while conservatives favor the latter. Regarding inter-generational political differences, they assert that younger Koreans have less of a “chip on their shoulders” about “perceived historical injustices” but also make the unsurprising observation of “the older generation trending conservative while the younger generation supports more progressive political leadership” (Glosserman and Snyder Reference Glosserman and Snyder2015, 75). This seems contradictory considering progressives’ energetic activism on Japan-specific historical issues. Yi, Phillips, and Lee (Reference Yi, Phillips and Lee2019, 494) observe that Korean liberals have successfully pluralized public discourse about North Korea and generated public support for inter-Korean rapprochement, but they argue that “no comparable groups generate counter-narratives about Japan.” Section 5, below, will demonstrate how conservatives have, in fact, attempted such counter-narratives—albeit with mixed success.

A pattern thus emerges of East Asian IR scholars characterizing South Korea as incredibly unified on Japan issues, while South Korean domestic politics scholars characterize it as incredibly divided on those same issues, with little interaction or debate between the two disciplines on the subject. This article seeks to bridge the gap.

My argument has some parallels with that of You and Kim (Reference You and Kim2020), who argue that Korean leaders pursue “diversionary” confrontation toward Japan when faced with rising disapproval over other issues. Their analysis is ideologically agnostic and finds this diversionary tactic to apply consistently across multiple administrations. However, their data stops at 2012, and again the sole conservative example of diversionary Japan hostility is Lee Myung-bak's Dokdo visit and surrounding events. My theory is broadly compatible with their general premise under liberal administrations, but I argue that conservatives will prefer using North Korea as their diversionary target when politically feasible. While I agree that liberal administrations may use anti-Japan diversion to counter various vulnerabilities, I contend that it is the only weapon in their arsenal emotionally potent enough to be effective against conservative anti-communism. Further, my theory challenges two of You and Kim's control assumptions—that an increase in contentious actions by North Korea will have a dampening effect on anti-Japan hostility, and that “hawks” (defined as the right) will be more confrontational toward Japan (You and Kim Reference You and Kim2020, 59–60). Section 5 will show how both assumptions have proven unreliable at several junctures since 2012.

3. Theoretical Framework and Case Selection

As observed earlier, South Korea's history and geopolitical location leave it uniquely vulnerable to anti-communist pressures. In Western-aligned democracies around the world, left and center-left parties often face misguided public suspicions of communist leanings, but these suspicions are exponentially compounded in places that have experienced communist takeover firsthand (Hungary, Poland, the Balkan states) or face a continuing threat from a communist adversary (the Philippines, India, 1950s US). Of all the democratic transitions in which a left-wing opposition toppled a right-wing dictatorship, South Korea is the only case that checks both boxes. With such fertile ground for anti-communist red-baiting politics, by rights it should have remained a nominally democratic right-wing populist regime like the Philippines, or at best a right-dominated democracy with a weak and fragmented leftist opposition like Japan. The fact that a progressive left has emerged there as a viable and competitive political wing is a historical aberration. Compounding the problem, the main liberal party is now associated with several costly failed ventures toward inter-Korean reconciliation, as detailed in Section 4. It is not within the scope of this article to debate either the merits of those endeavors or the seriousness of the North Korean threat to South Korea today. However, it is important to demonstrate that the South Korean left is even more vulnerable than leftists elsewhere to accusations of communist sympathies, and North Korea's continued provocations provide the conservative side with a steady supply of “red meat” (no pun intended) around election time.

Could the South Korean left have overcome such a handicap purely by promoting traditional liberal initiatives, such as labor laws, welfare programs, or civil rights protections? From what we know of the psychology of voting behavior, it seems doubtful. A large body of political psychology research has established that negative messages leave a stronger impression on voters than positive ones (Fridkin and Kenney Reference Fridkin and Kenney2004, Soroka and McAdams Reference Soroka and McAdams2015) and negative impressions drive voting behavior more than positive ones (Klein Reference Klein1991). Another well-established line of research has demonstrated that external threats can supersede domestic issues by generating a “rally-round-the-flag” effect (Foster and Palmer Reference Foster and Palmer2006, Groeling and Baum Reference Groeling and Baum2008). Less well-examined are questions of what happens when an external threat remains politically salient over an extended period, and whether one external threat might be invoked by a political opposition to counteract another.

In the South Korean context, we can think of North Korea and Japan as two looming gravitational wells of external negativity that each exert a continuous pull on South Korean politics, simply by existing and being what they are. Naturally, we expect a looming communist threat like North Korea to shift voters’ ideological center to the right. It is somewhat less intuitive what the Japan element does, but this paper contends that the various unresolved historical issues and tensions with Japan have shifted the center left of where it otherwise would be (for reasons explained in Section 4). This is a counterfactual argument, and as such notoriously difficult to prove or disprove. We can, however, come at it sideways by evaluating partisan discourse and tactics for signs that the issues of Japan and North Korea are played off against each other—i.e., that the left wields its strong position on Japan issues in direct response to, or mimicry of, the right's use of anti-communism, and vice versa.

Securitization theory (ST) (Buzan, Wæver, and de Wilde, Reference Buzan, Wæver and de Wilde1998) provides a framework for thinking about how foreign threats can be constructed by domestic actors. Developed in the European post-Cold War context, ST provides a framework for studying how issues are socially constructed as threats through “speech acts” uttered by “securitizing actors.” Importantly, ST defines the facilitating conditions of a securitizing speech act along two dimensions: the referent object that is purportedly threatened, and the social capital of the speaker as a person in authority (Buzan, Wæver, and de Wilde, Reference Buzan, Wæver and de Wilde1998, 33). Useful for our purposes, ST considers the target audience of securitizing speech as a “collectivity” that may be in rivalry with other collectivities within the society (Buzan, Wæver, and de Wilde, Reference Buzan, Wæver and de Wilde1998, 36–37). Applications of ST have usually focused on analyzing speech acts mainly by politicians seeking to either heighten or reduce the public perception of a threat. To apply these tools to our dueling antagonisms concept, we need to find evidence that South Korea's securitizing speech acts concerning Japan and North Korea not only diverge along partisan lines but also interact to counterbalance each other.

To begin, the following pair of hypotheses are formulated to capture the basic pattern:

H1a: Politicians on the South Korean left will be more vulnerable to public perceptions of being sympathetic to North Korea/communism.

H1b: Politicians on the South Korean right will be more vulnerable to public perceptions of being sympathetic to Japan.

If these hypotheses are correct, we should expect to see the following signs:

• Enthusiasm: Do leftist (rightist) politicians speak more volubly and passionately when circumstances call for remarks about Japan (North Korea) issues?Footnote 3

• Pivoting: Do rightist (leftist) politicians tend to pivot to unrelated topics when circumstances call for remarks about Japan (North Korea)?

• Non-sequiturs: Do rightist (leftist) politicians tend to bring up North Korea (Japan) issues unprompted more often than their counterparts?

• Over-scrutiny: Do rightist (leftist) politicians get more public attention than their rivals on their stance toward Japan (North Korea)? For instance, do right wing politicians get more scrutiny than their left-wing counterparts for similar chinil family connections or past pro-Japan remarks? Do attempts at inter-Korean reconciliation cause more controversy when proposed by a left-wing leader?

At the next level, we need to test whether these two antagonisms actually “duel” with each other or simply co-exist. That is, does the left push Japan issues simply as part of their general platform, or do they specifically use these issues to counterbalance their own vulnerability on North Korea? If the latter, we should expect to see anti-Japan rhetoric increase in times of heightened inter-Korean tensions or when liberals’ North Korea policy comes under scrutiny. Likewise, we should expect the right to lean into anti-communism when facing heightened scrutiny over their history with Japan. This is expressed in the following hypotheses:

H2a: Politicians on the left will increasingly use anti-Japan rhetoric in response to heightened public scrutiny of their policies/attitudes toward North Korea/communism.

H2b: Politicians on the right will increasingly use anti-communist rhetoric in response to heightened public scrutiny of their policies/attitudes toward Japan.

“Heightened public scrutiny” might be provoked by a recent policy reversal, a confrontational incident, or a public holiday commemorating past victims of either North Korea or Japan. For instance, if a right-wing politician pivots to talk of North Korea during a speech marking a public holiday for victims of Japan, or amid a debate over Japan policy, or immediately after being accused of having pro-Japan sympathies, this would be strong evidence for H2b. Likewise, if a left-wing politician pivots to anti-Japan rhetoric during public debate over a response to a North Korean provocation or at an event commemorating Korean war victims, this would be considered evidence for H2a.

If these hypotheses are correct, we can look for the following:

• Pivoting Non-Sequiturs: When pivoting away from the topic of Japan (North Korea), do rightist (leftist) politicians tend to pivot specifically toward talk of North Korea (Japan), more than other issues?

• What-aboutism: When the left (right) brings up past transgressions by Japan (North Korea), do their opponents tend to respond by drawing equivalence to transgressions by North Korea (Japan)? Is this comparison conspicuously more popular than others?

• Mimicry: Does the left deliberately mimic the right's language concerning the threat of North Korea/communism in its rhetoric about Japan? Does the left propose measures against pro-Japan sentiment that specifically imitate existing measures targeting pro-North or communist sympathies?

The bold terms above will be used as shorthand in the rhetorical analyses presented in Section 5. That section will sequentially examine political rhetoric during four focus episodes selected from periods during which we might expect to see the above type of rhetorical dueling—periods featuring 1) heightened partisan competition (e.g. preceding a close election) and 2) a recent development or historical anniversary prompting elite actors on both sides to issue speech acts clarifying their positions toward Japan. The “securitizing actors” whose speech acts are examined are predominantly political elites representing the major parties. However, another type of actor occasionally makes an appearance—civil society activists, particularly on social media. Before proceeding to the empirics, however, the following section provides context on the historical evolution of South Korea's partisan vulnerabilities with respect to Japan and North Korea.

4. Dueling Antagonisms: Anti-Japanism and Anti-Communism

i. The Northern albatross around Korean leftists’ necks

It is not easy being a leftist in South Korea when North Korea misbehaves, which is often. To make matters worse, the main liberal party is associated with several costly ventures toward inter-Korean reconciliation, each one presented with much fanfare by a liberal administration as an important step toward peaceful reunification, only to end in expensive failure. The Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization (KEDO) exists today only as a monument to $1.5 billion in wasted taxpayer funds. The historic 2000 summit that won President Kim Dae-jung his Nobel Prize was later overshadowed by reports that he paid $500 million for the pleasure of shaking Kim Jong-il's hand. The Mount Kumgang Resort and the Kaesong Industrial Complex, the two crowning gems of the Sunshine Policy, both proved to be costly lessons for South Korean companies in the perils of investing in North Korea. Conservatives have demonstrated a knack for connecting these failures to successive liberal administrations (Lee Reference Lee2018).

Compounding the difficulty, the Korean left must deal with continued accusations of dangerous North Korean sympathies. During the dictatorship period, intellectuals were jailed for possessing books by banned leftist authors from Bertolt Brecht to Karl Marx under the oppressive National Security Law (NSL). This archaic law is still used to marginalize liberal opposition (Doucette and Koo Reference Doucette and Koo2016); a scathing Amnesty International report showed that NSL prosecutions doubled under Lee Myung-bak, from 46 in 2008 to 90 in 2011 (Amnesty International 2012). While many of these are frivolous, like the 24-year-old sentenced to 10 months in prison in 2012 for retweeting North Korean propaganda as a joke, a few are actually justified: in 2013, the far-left United Progressive Party (UPP) was charged under the NSL with “inciting an insurrection” after secret recordings revealed that members had plotted to assist a North Korean takeover (Lee Reference Lee2014). Such incidents may not be representative, but they live long in public memory and prop up long-held preconceptions. To this day, many older conservatives believe that the bloody Kwangju uprising of 1980 was provoked by pro-North agents, and similar conspiracy theories were raised about the 2017 impeachment protests.

Relatedly, polls show a distinct partisan divide in attitudes toward North Korea. The 2020 IPUS survey confirms that, while North Korean threat perceptions fluctuate over time with various developments, there is a consistent partisan divergence over time, with conservatives feeling more threatened than progressives (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Respondents Who Identified North Korea as Greatest Threat (%) (IPUS 2020, p. 146)

What does this have to do with anti-Japanism? Let us compare the situation in Taiwan, the other long-term Japanese colony and current spoke in US alliance. Locked in an ongoing confrontation with communist China, we might expect Taiwan's center-left to face similar McCarthyist pressures. But unlike South Korea, Taiwan's partisan divide has always been based more on identity than ideology, focused on the question of separation from China, with liberals solidly on the side of independence (Mobrand Reference Mobrand2020). Since no reasonable person would accuse Taiwan's Democratic Progressive Party of being secretly in league with the Chinese Communist Party, they do not need to waste energy redirecting public concern away from China toward an alternative target like Japan.

ii. Pro-Japanese roots of Korean conservatism

The dominant conservative party today is descended from the Democratic Republican Party (DRP) that controlled South Korea through the period of high growth military dictatorship from 1963 to 1980. This high growth was substantially supported by large loans and reparation payments from Japan, and many old-guard conservative leaders have uncomfortable family histories of collaboration with the Japanese colonial regime. Most notably, Park Chung-hee, the head of the DRP military regime, was educated in Manchukuo and had a well-documented affinity for Japanese modernity and martial culture. To this day, Korean liberals sometimes refer to Park disparagingly by his Japanese name and military rank, Lieutenant Takagi Masao. Many of Park's most reliable contemporaries in the DRP military dictatorship had similar early-career backgrounds of Japanese military training or education, and some of today's most prominent conservatives—including Park Geun-hye and Kim Moo-sung—are their descendants. Unsurprisingly, investigations into colonial collaboration were firmly suppressed under the DRP (De Ceuster Reference De Ceuster2001).

After democracy consolidated in the 1990s, the public's long-repressed desire for postcolonial justice fueled an energetic movement to prosecute former collaborators and their descendants. Early groundwork laid in the 1990s culminated in the creation of formal investigative mechanisms under the liberal administrations of the early 2000s. The Special Law on the Inspection of Collaboration for Japanese Imperialism, enacted in 2004, lays out legal criteria for “pro-Japanese and anti-national actions” committed during the colonial period. A second law, passed in 2005, allowed for assets to be confiscated from collaborators’ descendants and redistributed to the descendants of independence fighters. During the progressive Roh Mu-hyon administration, two separate investigatory commissions were launched—a civic organization called the Institute for Research in Collaborationist Activities (IRCA), and the presidential Investigative Commission on Pro-Japanese Collaborators’ Property (ICPCP). From the beginning, there was a sharp partisan divide on these investigations, with 115 of the 121 conservative National Assembly members voting against creating the presidential commission. The late Roh era was a time of many startling revelations from these investigations: the IRCA's first Encyclopedia of Pro-Japanese Figures, released in 2009, named 4,389 alleged collaborators including many celebrated artists, writers, and scholars who had previously been respected or even revered. Meanwhile, the ICPCP began confiscating real estate from its own much shorter list of 114 key individuals, most of them descended from well-known figures from the early history of annexation. The formal investigations subsequently languished under conservative rule (McGill Reference McGill2014), but their findings set the stage for renewed and very public examinations of politicians’ family histories in the Moon Jae-in era—as will be explored in Section 5.iii.

It is important to understand the historical context of such investigations. The idea of yŏnjwaje 연좌제, or guilt by association, has deep roots in Korean culture, particularly in the suppression of suspected leftists and pro-North elements throughout the dictatorship period (Suh Reference Suh2010), and normalizes the idea of relatives and associates paying a price for one's crimes. Once mostly used against those with family connections to North Korea, yŏnjwaje was ruled unconstitutional in 1980, but it remains a potent political weapon for attacks against public figures. Such practices have conditioned Koreans to accept listing and weaponizing family histories as a legitimate political tactic and fair turnaround. But there is a deeper layer here, in that the educational and financial benefits of colonial collaboration truly did cast lasting repercussions on the distribution of wealth and power in post-liberation South Korea (De Ceuster Reference De Ceuster2001, McGill Reference McGill2014). Thus, the confiscation of property inherited from colonial-era collaborators can be interpreted as an alternative vision of redistributive justice for Korean liberals—one that avoided direct socialist connotations, while conflating the depredations of the colonial era with the pernicious wealth gap of the high-growth era.

Meanwhile, one of Park Chung-hee's most significant legacies—his negotiation of the 1965 normalization of relations with Japan—came under renewed examination and introspection. The terms of this treaty secured significant funds from Japan that enabled Korea's rapid economic growth and modernization, but they left many key historical issues unaddressed, most notably the question of reparations for wartime forced labor and sexual slavery and the disposition of the disputed islets of Dokdo. Furthermore, this oversight became explicitly linked to anti-communist politics and Cold War expediency, as mass protests against the treaty were brutally put down (Lee Reference Lee2021). To press these issues today is to attack one of the core legacies of the DRP regime and, by proxy, its successors in today's conservative party.

The DRP regime had also preserved many physical edifices associated with the Japanese colonial state. After democratization, this bestowed upon the newly empowered left several very visible symbols of the hated colonial administration to destroy. During the period of liberal electoral ascendance in the 1990s, many of these were cathartically demolished or repurposed in ways that symbolically linked the DRP dictatorship and the Japanese colonial government. A prime example is the infamous Seodaemun Prison, where many renowned independence fighters had been tortured and killed in the colonial era. The complex, located in central Seoul, remained intact and continued to be used as a prison throughout the military dictatorship period. The prison was finally shuttered in 1987, the year of the first competitive presidential election, and it reopened in 1992 as a museum and memorial. Today one may tour the grounds and peer into the cells where many pro-democracy dissidents, some of whom later became prominent liberal politicians, were once detained in the same physical buildings that had housed the heroes of Korea's independence struggle. The museum's exhibits draw a continuous line from the Japanese colonial era through the successive autocratic regimes up to 1987. In section 5, we will see how Seodaemun Prison and similar liberation monuments became popular backdrops for liberal party campaign events and speeches.

Thus, along with healthy political competition, the democratic era saw the increasingly partisan appropriation of colonial sites and symbols, along with the long-delayed launch of investigations into colonial-era collaborators conspicuously promoted by liberal administrations (and avoided by conservative ones). As the ascendant center-left established itself as the champion of historical reckoning and addressing colonial-era injustices, the still-powerful center-right found itself in an unfamiliar defensive position over historical issues, with increasing political and financial consequences for members with unfortunate pro-Japan backgrounds, but with a vestigial anti-leftist legal apparatus to fall back upon. Thus the stage was set for the dueling partisan portrayals of pro-North Korean left and pro-Japanese right that have characterized South Korean politics ever since.Footnote 4 This domestic partisan dynamic, more than any regional geopolitical development or behavior by Japan, is the principal reason why tensions with Japan have increased since South Korea's democratization.

5. Partisan Discourse on Japan and North Korea

i. Territoriality over territory, 2012

Our first focus episode covers the period around conservative President Lee Myung-bak's August Reference Lee2012 visit to Dokdo. This period presents an important test case because it preceded a very contentious presidential election, and as mentioned many scholars point to Lee's Dokdo trip as the primary evidence of Korean bipartisan alignment on Japan issues (Lai Reference Lai2020, You and Kim Reference You and Kim2020).

Before Lee became the first sitting South Korean president to visit the tiny islets of Dokdo, his reputation on Japan policy was in tatters from his recent disastrous attempt to push through a General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA). Lee was rare among conservatives for having an impeccable anti-chinil and anti-DRP background, having been imprisoned at Seodaemun in his youth for protesting the 1965 normalization treaty with Japan. This background protected him from easy chinil accusations and gave him greater flexibility particularly on the Dokdo problem (a consequence of that 1965 treaty). This could have been a rare opportunity to present a bipartisan united front against Japan. Yet liberal politicians seemed uneasy with the conservative party leader stepping on their turf right before an election, particularly as it deflected from the GSOMIA debacle. A spokesman for Moon Jae-in, then the leading liberal presidential candidate, immediately released a statement expressing skepticism:

There are ample grounds for doubting the sincerity of President Lee Myung-bak unexpectedly visiting Dokdo right before an election … The Lee administration has consistently kept a low posture arguing for ‘quiet diplomacy’ in response to Japan's constant historical distortions and claims to Dokdo. Even worse, they recently pursued a security agreement with Japan without informing the public or the National Assembly … We hope that Lee's Dokdo visit is not just a one-off event to cover the criticisms of his low-posture diplomacy toward Japan. If the president wants this Dokdo visit to be evaluated as a genuine defense of sovereignty, he must also announce proper follow-up measures on the ‘five major historical issues’ for developing Korea–Japan relations proposed by Candidate Moon Jae-in (Lee Reference Lee2012)

This last was a reference to a major campaign speech Moon had delivered one week earlier, excoriating Lee Myung-bak's “passivity” toward Japan on five major issues, including Dokdo: “Japan's Defense White Paper again claimed Dokdo is Japanese territory … We cannot accept this. We cannot overcome this by pretending, like Lee Myung-bak, that it's no big deal” (Lee Reference Lee2012). It is unclear whether Lee had already decided to visit Dokdo at the time of Moon's speech.

That same speech also took aim at Moon's chief campaign rival, Park Geun-hye, whose family history on Japan matters was much more complicated than Lee's. Moon alleged that Park's late father, the former President Park Chung-hee, had “lacked historical awareness” toward Japan, citing as evidence rumors that he had once said he would like to bomb Dokdo off the map. Park Geun-hye's camp promptly denied the allegation, issued a report claiming the comment had actually been made by the Japanese side, and demanded that Moon apologize for “spreading misinformation.” Moon then pointed to a declassified US State Department memorandum indicating that at one point during the negotiations over the 1965 normalization treaty, while expressing his vexation over the Dokdo issue to US Secretary of State Dean Rusk, “President Park said that he would like to bomb the island out of existence to resolve the problem.” Moon witheringly characterized the Park campaign's denial as “the outdated politics of always denying inconvenient truths.” A somewhat deflated Park campaign spokesman responded, “Numerous documents released in Korea and abroad clearly demonstrate President Park's firm determination to defend Dokdo … Yet candidate Moon's side took a single line from one particular American memorandum and tried to distort President Park's position for strategic gain” (Son Reference Son2012).

Subsequent developments revealed further skepticism of conservative intentions regarding Dokdo. When, days after Lee's Dokdo visit, the director of the Korea Institute for National Unification (KINU) penned a tentative proposal for a possible resource-sharing solution for Dokdo, liberal party representatives were quick to denounce him as “chinil” and demand his ouster. Although the KINU director was appointed by the prime minister, netizen comments showed that outrage quickly focused on President Lee: “Why are there so many guys like this around [Lee Myung-bak]?” “Bringing in people like this is proof that President Lee and the [conservative] Saenuri Party are a pro-Japan traitor regime” (Jin Reference Jin2012). The public backlash was so swift and devastating that the prime minister was compelled to denounce his own appointee (Son Reference Son2012). Here we see our first evidence of social media activists as “securitizing actors” contributing to the rhetoric and bringing real political consequences for even modestly conciliatory stances toward Japan.

The above suggests that Korean liberals feel somewhat territorial over the Dokdo issue and are reluctant to surrender it as a point of conservative vulnerability, in line with H1b. We have not yet seen evidence of conservatives pivoting to North Korea, however—perhaps because at that point conservatives were less keen to bring up North Korea issues, having overseen a series of deadly incidents during Lee's tenure. For that we will have to turn to a different election and a different political moment.

ii. Dueling March 1st rhetoric, 2017

Our second focus episode occurs during the snap election that followed President Park Geun-hye's impeachment in early 2017, after a series of shocking revelations about corruption within her administration prompted widespread demands for her removal. The remnants of the conservative party were reeling after a long winter of enormous weekly candlelight protests and the successive downfall of many top party leaders affiliated with Park. Liberals were ascendant, and even progressive-left candidates seemed competitive. But just when it seemed like the embattled president did not have a single supporter left, there appeared rival “Taegŭkgi” (Korean flag) rallies attended mostly by elderly pensioners. Many participants subscribed to a conspiracy theory that the scandal and impeachment were orchestrated by North Korean agents or pro-North sympathizers—representative of our non-sequitur concept. One septuagenarian veteran in the crowd summed up his position to a reporter thusly: “It's a matter of supporting a liberal democracy or communism. There's no left or right. Just think of the leftists as people close to the North, and the rightists as people close to the U.S.” (Kang Reference Kang2017). Despite their efforts, the National Assembly voted overwhelmingly for impeachment, and the Constitutional Court would rule to remove her from office on March 10.

At the height of all this came March 1. March 1st is a major patriotic holiday in both South and North Korea, marking the day in 1919 when a group of Korean patriots declared independence from imperial Japan, sparking nation-wide protests that were brutally quelled. The annual event was already known as a time for political speeches, but in 2017 the celebrations came at a critical moment, as rival candidates were gearing up for the short campaign period before the anticipated snap presidential election. It was a natural opportunity for the various party leaders to reaffirm their nationalist bona fides and to contrast their faction's stance with the competition's. As the holiday is ostensibly about patriotic resistance against Japan, the candidates’ remarks provide an opportunity to evaluate relative degrees of either enthusiasm or pivoting from that topic, and the abundance of candidates (fifteen were actively competing at the time) allows for comparison across the full political spectrum.

At the time, three candidates were competing in a close primary for the main liberal party's nomination: Moon Jae-in, Seongnam Mayor Lee Jae-myung, and South Chungchŏng Governor Ahn Hee-jung. Moon Jae-in chose to give his remarks from the Seodaemun Prison Museum, flanked by giant posters of colonial-era independence fighters who had perished within its walls. Clad in a traditional durumaki garment, waving a Korean flag and backed by a row of schoolgirls, he declared the recent “candlelit vigil” marchers to be “the true successors of the March 1st movement.” His speech focused on chastising the current government's historical revisionism and protection of chinil members. Moon remarked:

Even now, nearly a century from the founding of the Republic of Korea, we have not yet been able to create a truly democratic republic in which the people are the real sovereigns …

The time for eradicating chinil elements must not exceed 100 years. The unexpurgated chinil forces carried on into the dictatorship and have taken root in our Republic, and now they even aspire to manipulate history. This is an unacceptable shame for the Republic (Park Chŏng-yŏb Reference Park2017).

The phrase “a century from the founding” was an oblique reference to a recent textbook controversy in which the conservative government had attempted to establish a state-approved textbook that downplayed the crimes of colonial collaborators and whitewashed many aspects of DRP rule. Among other things, this textbook claimed that the Republic of Korea was founded in 1948, while liberal civic groups insisted that it dated back to the Independence Declaration of 1919, the raison d'etre of the March 1st holiday.

Rival candidate Lee Jae-myung, a left-wing populist sometimes called “Korea's Trump,” delivered remarks from the historic site of Korea's independence declaration, Pagoda Park in downtown Seoul. Like Moon, he praised the recent candlelight protests as “the second March 1st movement.” Lee also made a reference to Park's failed history textbook reform, saying it reflected “not a national history that fosters ‘national pride’ but rather a colonial mindset that conforms with Japan's intentions,” and controversially compared the right's ineffectual efforts to curtail the candlelight protests with the “white terror” state violence inflicted against democracy activists in the 1980s (Kim Dong-ho Reference Kim2017). By contrast, center-left primary contender Ahn Hee-jung spoke before a group of Korean War veterans and called for unity, declaring “Kim Ku, Rhee Syngman, Park Chung-hee, Kim Dae-jung, and Roh Mu-hyun were all part of our proud history” (Park Chŏng-yŏb Reference Kim2017). By naming past presidents representing both left and right alongside universally beloved independence fighter Kim Ku, the moderate candidate seemed to be extending an olive branch to the beleaguered but still potent center-right.

Shim Sang-jŏng, the candidate for the far-left Justice Party (a remnant splinter of the disbanded UPP), spoke at Seodaemun Prison the day before. Her remarks focused on historical reckoning, saying she would “clean up the remnants of pro-Japanese collaboration and end the history of constitutional abuse.” Pressed for specifics, she proposed establishing a “Museum of Pro-Japanese Anti-Nationalist History,” said that the colonial collaborators named by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 2009 should be listed in history textbooks, and demanded that those individuals be stripped of the honors they received (Park Reference Park2017).

The more neutral Ahn Cheol-soo, a popular independent who had recently co-founded the centrist People's Party, spoke at the Ahn Jung-geun Memorial Museum, which commemorates the eponymous resistance fighter who assassinated the first Japanese governor of Korea in 1909 (candidate Ahn has claimed to be the late Ahn's “descendant” (후손) in the sense that he belongs to the same clan). Ahn used his remarks to condemn the pro-Park flag rallies, saying it was wrong to use the Korean national flag as a symbol for such a divisive movement. Fellow People's Party candidate Son Hak-gyu, an established center-left choice, visited the Seodaemun Prison Museum and sought out the cell of his late colleague Kim Geun-tae, a democracy activist imprisoned and tortured under the DRP regime who later became a liberal party leader. Son's remarks focused on economic growth but also highlighted the historical achievements of independence fighters (YTN 2017).

By contrast, conservative candidates seemed eager to move beyond colonial history. Nam Kyung-pil, the mayor of Gyeonggi Province and candidate for the far-right Bareun Party, posted on his official Facebook page: “Now is the time to talk of hope for the future, not anger over the past … What the people want right now is not conflict and confrontation but stability and harmony” (Park Chŏng-yŏb Reference Kim2017). Fellow Bareun Party candidate Yoo Seong-min, speaking from the National Cemetery in his hometown of Daegu, sought to link March 1st to the modern conservative movement:

Behind the March 1st Movement was an indomitable will and fighting spirit to carve out the fate of the nation and its people against the oppression of the Japanese colonial government. Now is the time to inherit the spirit of the March 1st Movement … By completing the conservative revolution, restoring our broken community, and putting the Republic of Korea back on solid ground; only then will we inherit the true spirit of the March 1st Movement. (Bae Reference Bae2017)

Hong Jun-pyo, a defense hawk who had emerged as the leading mainstream conservative as the dust cleared from Park's impeachment, badly needed to distance himself from Park and thus delivered one of the most stridently anti-Japanese conservative speeches. Speaking at a public auditorium in his home province before a mixed group of independence activists’ descendants and Korean War veterans, he condemned Park's 2015 Comfort Women agreement as a “back-door deal” and “a billion yen bargain” for Japan and compared Japan's Comfort Women policy to Nazi war crimes. But he also ominously warned, “While leftist regimes have fallen to rightists across Central and South America and Europe, only our country is still swept up in a leftist frenzy,” predicting that liberal policies would drive businesses offshore (Kim Sŏng-chan Reference Kim2017). This seems suggestive of a pivoting non-sequitur—taking time from a speech commemorating the anti-Japanese resistance to warn of creeping socialism. Former floor leader Won Yoo-chul, then competing with Hong for the mainstream conservative nomination, issued a Facebook statement bemoaning the ongoing dueling rallies in Seoul: “The whole nation should be coming together to celebrate the March 1st Independence Movement with Korean flags, yet even today Kwanghwamun Square will be divided into candles and flags, provoking extreme division” (Bae Reference Bae2017). This seems to fit our description of pivoting away from the historical significance of the holiday, though unlike Hong he refrained from pivoting specifically toward an anti-communist non-sequitur.

Through the above we can see how each faction's reputation on Japan issues influenced its candidates’ messaging on a patriotic holiday at a critical moment for South Korean politics. Liberal and progressive candidates displayed a high level of enthusiasm for the holiday, choosing their words and venues carefully to highlight their strong anti-Japan credentials and lingering on unresolved colonial history issues. Centrists, sensitive to the left-ascendant political winds of the moment, showcased their own favorable personal and family connections to the anti-Japan struggle where available, but generally promoted a more unifying and forward-looking message. Conservatives mostly avoided colonial historic sites and seemed eager to skim over the historical significance of the holiday while pivoting quickly to economic or security issues. All sides sought to lay claim to the “true spirit” of the March 1st movement, but for conservatives this led far away from colonial history to appeals for a “conservative revolution” and non-sequitur warnings of “a leftist frenzy.”

An ideal comparative test would also examine competing candidates’ speeches on a major anti-communist holiday to see if liberals display similar pivoting non-sequiturs when the tables are turned. Unfortunately, there has not yet been a major contentious election period falling on such a day. One alternative would be to compare the annual Memorial Day speeches (usually an occasion for commemorating fallen Korean soldiers) of successive presidents. For instance, Moon Jae-in's first Memorial Day speech, shortly after winning the 2017 election, included a lengthy pivoting non-sequitur on how “the children and grandchildren of independence fighters have lived in poverty while the children and grandchildren of pro-Japanese collaborators have thrived” (Moon Reference Moon2017). This sort of comparison is less fruitful, however, because comparing speeches across time would capture inconsistent levels of partisan vulnerability and public scrutiny on the relevant antagonism; even the most conservative president cannot avoid criticizing Japan when a major dispute erupts.

iii. Dueling frames: South–North vs Korea–Japan, 2019

Our third episode begins with the Japan–Korea trade dispute of 2019 and leads into the General Assembly election of spring 2020. Triggered by a South Korean Supreme Court ruling on Japanese war reparations and coinciding with a near withdrawal from GSOMIA (the security agreement with Japan that passed in 2016), this series of events presents a good test as it brings our dueling antagonisms into direct confrontation in a period of peak partisan competition. It also constitutes the greatest challenge yet to existing theoretical expectations for South Korea to prioritize security and trade above anti-Japan sentiment in a time of “dovish” leadership and declining US commitment to bankroll Korea's security (Cha Reference Cha1999, You and Kim Reference You and Kim2020).

Bilateral tensions had been simmering since late 2018, when South Korea's Supreme Court ruled that certain Japanese companies must compensate descendants of Korean victims of colonial-era forced labor. Tensions reached full boil when Japan announced new export restrictions against South Korea in July 2019. That summer a coalition of Korean civic groups led a largely successful nationwide “No Japan” campaign to boycott Japanese products (the boycott discussed in the introduction) (Figures 1 and 2). Concurrently, that August the Moon administration announced its intention to unilaterally terminate GSOMIA, essentially pitting anti-Japan sentiment directly against North Korean threat perceptions. A November 2019 survey showed that the public was clearly divided over the decision along partisan lines (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Poll: Do you support terminating the GSOMIA agreement? Data from Realmeter 2019

At this point, the main liberal party controlled the Blue House and had a razor-thin plurality (with a one-seat lead over the main conservative party) in the National Assembly. The upcoming National Assembly election of April 2020 was already set to be contentious, with conservatives still reeling over the Park impeachment and liberals facing mounting criticism over the floundering economy and the president's unrequited engagement policy toward Pyongyang. As North Korean belligerence increased, the dueling antagonisms increasingly came into play. In his March 1st speech for 2019, President Moon Jae-in made the explicit connection between colonial-era collaborators and present-day red-baiting:

Hostility between the left and the right and ideological stigmas were tools used by Japanese imperialists to drive a wedge between us. Even after liberation, they served as tools to impede efforts to remove the vestiges of pro-Japanese collaborators … . Still now in our society, the word “Reds” is being used as a tool to vilify and attack political rivals, and a different kind of “Red Scare” is running rampant. These are typical vestiges left by pro-Japanese collaborators, which we should eliminate as soon as possible. (Moon Reference Moon2019)

Two weeks later, conservative floor leader Na Kyung-won seemed to directly challenge this historical account in National Assembly remarks: “The post-liberation Anti-National Activities Committee [반민특위] tore the country apart, and such a war must never be repeated” (YTN 2019). This referred to a committee formed in 1948 to investigate colonial collaborators, which was terminated after only one year amid the more urgent task of suppressing communism. Na was already facing censure for accusing Moon of being a “spokesman for Kim Jong-un,” remarks that had provoked a near-riot on the floor days earlier. With these two speeches, Na set herself up as a chinil apologist and reified Moon's framing of contemporary politics as a battle between anti-Japanese and anti-communists. Soon after, the term t'ochak waegu 토착왜구Footnote 5 began circulating in liberal social media, and a series of memes by liberal activists appeared declaring “The National Assembly election is a Korea–Japan battle” and calling on voters to “eradicate the t'ochak waegu.” Conservative social media counterattacked with what-aboutism, releasing similar memes bearing the slogans “The National Assembly election is a South–North [Korea] battle” and “Eradicate pro-North Koreans who support dictators.” (Figure 5)

Figure 5. Dueling 2020 Campaign Posters. From left: Independence martyr Ahn Jung-geun's iconic handprint over the slogan “The National Assembly election is a Korea–Japan battle”; the same slogan over a pig with teats labeled for the conservative party and right-leaning newspapers; a blood-streaked Kim Jong-un over the phrase “The National Assembly election is a South–North battle.” Source: Newstof 2019

This grass-roots slogan was taken up later by a liberal campaign group as the official slogan for a series of posters targeting alleged chinil conservatives up for reelection. That campaign also borrowed the “No Japan” slogan and logo employed by the Japanese product boycott movement (Figure 6). Representative Min Kyung-wook, one of those targeted, attempted to turn the tables by launching a similar poster campaign accusing prominent liberal leaders of having chinil backgrounds. Interestingly, the conservative posters focused on liberal candidates’ family connections to colonial-era collaborators, while the liberal posters focused on recent statements or actions by the candidates themselves—likely because such evidence was more abundant, and also possibly because years of anti-chinil campaigns targeting conservatives had left their ranks relatively well-purged of problematic ancestries, while the liberal side ironically retained more of such targets.

Figure 6. Dueling posters targeting alleged chinil candidates in the 2020 election. Left: “Chinil politician target list for 21st general election.” Source: public Facebook page for NoJapan415 campaign (@NOabeaction). Right: “Respond, chinil descendants … Yes, let's have a Korea–Japan fight in next year's general election.” Source: public Facebook page for Rep. Min Kyung-wook (@minkyungwook)

Meanwhile, as the trade dispute heated up that July, National Assembly lawmakers from both sides exchanged heated remarks after a liberal-proposed package of retaliatory economic measures against Japan stalled when conservatives blocked the supplementary budget needed to pay for it. Liberal leaders seized the opportunity to point up conservatives’ vulnerability on Japan at a Party Supreme Assembly meeting the next day, employing rhetoric filled with Korean colloquialisms implying treachery. Most outspoken was liberal floor leader Lee In-young: “They focus only on criticizing the administration and constantly back-tackling; that's how to become an ‘X-man’ for Japan … . The [conservative] Party should reflect on their words and actions if they want to know why people criticize them as ‘X-men for Japan.’”Footnote 6 Representative Sŏl Hun added: “Political divisions help the Abe government … If the [conservative] party clumsily tries to divide the government and the people, it will face a headwind” (Choe and Park Reference Choe and Sŏng-jin2019).

Conservative rhetoric displayed clear frustration over rising anti-Japan sentiment and suspicions that the whole crisis was politically calculated to hurt their election chances. They accused liberals of deploying excessive enthusiasm against Japan and over-scrutiny of alleged pro-Japan politicians. Representative Hwang Kyo-ahn complained, “Is it right to label anyone as pro-Japanese just because they might have slightly different views with the administration? Even if the entire nation came together to respond to the issue, the problem would still be difficult to solve. But does dividing sides as pro- and anti-Japan contribute to the resolution of the situation?” Another senior conservative remarked, “We are saying that we should look at the situation from a level-headed perspective, but they accuse us of being Japan-friendly. Since anyone who opposes the government ends up being labeled pro-Japan, we are in a disadvantageous position when it comes to public opinion. It is difficult to even mention the topic.” Na Kyung-won plainly accused the liberal party of pivoting: “There seems to be no willingness to overcome the national crisis, but only to prepare for the general elections … The administration tried to sell North Korea [policy] and now it's selling Japan. They're trying to cover up their incompetence and irresponsibility with a pro-Japanese frame.” (Choe and Park Reference Choe and Sŏng-jin2019). Such rhetoric may have made strategic sense from the perspective of conservatives stronger on North Korea issues, but it seems like a non-sequitur given that the current issue on the table, and the overwhelming focus of public preoccupation that summer, was Japan. Representative Min Kyung-wook posted to Facebook: “Any way you look at it, this does not seem like a strategy to benefit the country and win the trade war with Japan. It is solely a partisan political strategy aimed at next year's general election.” This sentiment was somewhat validated a week later when it emerged that the liberal party-affiliated Minju Research Institute (민주연구원) had emailed 128 liberal lawmakers a confidential report finding that a trade dispute with Japan would favorably benefit their election chances. These remarks imply an assumption of conservative vulnerability on Japan issues in line with H1b, which seems validated by the public response—conservative support dropped 3.2 per cent that month (Park Reference Park2019).

Suspicions about conservatives’ seeming reluctance to punish Japan dovetailed with the aforementioned “Korea–Japan battle” campaign, reviving interest in research into collaborator descendants. Unlike the IRCA/ICPCP investigations of the 2000s, which had been focused on confiscation and redistribution of collaborator descendants’ property, this campaign was explicitly political in nature and focused on conservatives up for re-election (Figure 6). Conservatives tried turning the tables. Min Kyung-wook scribed a lengthy Facebook post asserting that Moon Jae-in's family was “three generations of chinil” and listing the alleged chinil connections of several other prominent liberals including Seoul Mayor Park Won-soon (whose father allegedly helped recruit comfort women). The post also exhibited a pivoting non-sequitur by alluding to “Moon Jae-in and his pro-North Korea leftist party.”

Meanwhile, a clearly frustrated Na Kyung-won vented her spleen in a radio interview:

This government is always trying to frame the right-wing party as descendants of collaborators, and now they're carrying this chinil talk into the general election. We want to ask them, aren't there more chinil in the [liberal] party? Shall I name them all? Compared to them, our [conservative] party does not have any chinil worth the name. If you looked it up, they probably beat us about 10 to 1 … If we're splitting hairs, President Moon Jae-in was a lawyer representing a chinil descendant in a property restitution lawsuit against the state. If any members of our party had done that, they would be buried as chinil and couldn't even run for the National Assembly. (CBS Radio 2019)

Na was referring to the fact that, as a lawyer in 1987, Moon Jae-in had represented the family of the late Kim Ji-tae in a lawsuit that successfully recovered 5 billion won from the government. Kim Ji-tae had been named in the first collaborator list issued by the IRCA in 2005 on the grounds that he had worked for the infamous Oriental Colonization Company (동척) and received a substantial land grant from the colonial government. Most suspiciously for conservatives, Kim's name was omitted from the later IRCA Encyclopedia published in 2007; some alleged that Moon himself had interceded on his former client's behalf. This episode illustrates how tangled the partisan battles over colonial history have become and suggests that conservatives perceive a double standard in investigations of family backgrounds, which relates to our concept of over-scrutiny.

Whether by accident or design, these rhetorical battles set the April 2020 election up as a binary choice between hardline anti-North Korea and hardline anti-Japan. Ironically, by the time the election rolled around, the Covid-19 crisis had taken precedence over both issues, and some of the anti-North Korea rhetoric was belatedly diverted to anti-China.

iv. Legislating memory, 2020

Our final episode comes in June 2020, with the debates around the proposed Act on the Prohibition of Falsification of History (역사왜곡금지법), proposed by 31 liberal lawmakers. At this time liberals were riding high, with control of the Blue House and a supermajority in the National Assembly, which gave them the ability to fast-track bills with little resistance. In this context it is striking that, instead of attempting to finally repeal the outdated and oppressive NSL (as liberals tried and failed to do in the 2000s under Roh Mu-hyon), they instead seemed to be cynically proposing its liberal analog. The stated purpose of the bill was to “promote correct historical consciousness.” Proposed as an addendum to the already controversial May 18 History Distortion Act, which aimed to prohibit false statements related to the May 18 (Kwangju) uprising, this bill went further in prohibiting the spread of false information about any “historical fact,” explicitly invoking colonial-era history and the Sewol Ferry disaster. It also included criminal penalties for anyone who “praises, incites, or sympathizes with Japanese organizations that seek to justify colonial rule.” Strikingly, this clause exhibits strong mimicry of the notorious clause 7 of the NSL, which penalizes “any person who praises, incites or propagates the activities of an anti-government organization” (referring to the North Korean state and its sympathizers). Furthermore, the proposal spoke of the need to promote “correct historical consciousness” and prevent “propagation of wrong historical awareness and division of public opinion,” language uncannily similar to past charges laid against progressives prosecuted under the NSL.

Public discussion indicated that Koreans immediately framed the question in terms of pro-Japan speech versus pro-North speech. It was pointed out that, under Moon's new North Korean engagement initiative, in 2018 even people marching in the street praising Kim Jong-un could not be arrested under the NSL, yet this law would penalize anyone who suggested Japanese colonial rule had some benefits. A Korea Herald editorial fretted, “If the [liberal] party is asked to enact a bill to punish those who raise doubts about or deny the historical fact that North Korea invaded South Korea, starting the Korean War on June 25, 1950, is it willing to do so?” (Korea Herald 2020) Meanwhile, conservatives demanded similar laws targeting historical distortions of the Cheonan incident and the Korean War—both acts of North Korean aggression whose facts are occasionally disputed by far-left progressives (Song Reference Song2020). This suggests a full turnaround of what-aboutism and mimicry —an anti-communist law mimicking an anti-chinil law mimicking an anti-communist law (the NSL), supportive of hypotheses H2a and H2b.

To their credit, many left-leaning Korean academics and influencers spoke out against the bill. One law professor wrote in an editorial that such narrative-controlling laws were “only possible in totalitarian states like Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union” (Lee Reference Lee2020). Objections flooded a Seoul National University alumni message board, such as “If this law is enacted, anything considered by the government to be distorting history will be banned and subject to criminal penalties” (Kim and Choe Reference Kim and Wŏn-guk2020). One Korean doctoral student posted his concerns on Facebook: “The real problem is that … the current ruling party is, just as their opposition conservative party did, more often utilizing anti-Japanese history as a tool to win public support … Enough is enough, South Koreans suffered enough from the National Security Law, and I don't want to see two NSL's in South Korea.”Footnote 7 Such objections underscore the important role of moderates in combatting the cynical tactics of pitting one restrictive measure against another.

The bill stalled in judicial review. However, this was not the first attempt by the liberal party to incorporate pro-Japan sentiment into the legal code. There were previous attempts in 2004 and 2014 that failed to pass the judiciary committee. Of course, these legislative proposals can be explained as rational opportunism for an ascendant liberal party, part of the natural pendulum swing back toward liberal dominance after years of conservative administrations similarly attempting to impose their version of history and national security. What is striking, though, is that the now-empowered liberals are unapologetically proposing mirror-image laws and even coopting the conservative language of historical “correctness,” rather than attempting to repeal the NSL and champion broader civil liberties for all. If the liberal party has abandoned hope of repealing the NSL and instead committed to pushing for reciprocal laws targeting right-wing opinions, such a strategy would support the aforementioned finding (Fridkin and Kenney Reference Fridkin and Kenney2004) that negative messages motivate voters more efficiently than positive ones. It also suggests that Korean liberals have found that negative messages about alleged pro-Japan revisionism are their most convincing means of countering conservative messages about the national security threat of communism.

6. Conclusion

The puzzle of South Korean anti-Japan sentiment is its continued vehemence over time and its high salience in day-to-day domestic politics. It is easy to arouse public anger over recent injustices, but few democratic societies can maintain that level of antipathy decade after decade, as memories recede, life gets more comfortable, and other crises divert public attention. The modern South Korea–Japan relationship is thus an anomaly among postcolonial reconciliation dyads.

The rhetorical battles examined above lead to the question: How much is the South Korean left–right dynamic, with its unresolved Cold War energy, responsible for inflaming Japan issues today? We have seen considerable support for H1a and H1b, showing that the right is vulnerable on Japan issues just as the left is vulnerable on North Korea; their rhetorical battles display clear disparities in enthusiasm, pivoting and non-sequiturs on their respective topics. The evidence that these antagonisms are actually “dueling” (H2a and H2b) is somewhat less clear, but what-aboutism and mimicry seem to be increasing over time, especially under the Moon administration, and carrying increasing legal consequences—most significantly through the expansion of colonial collaborator lists and historical distortion laws.

We have also observed that politicians sometimes seem boxed in by public anger and civil society activism, particularly on Japan issues. This leads to another important question: does public sentiment drive elite rhetoric, or vice versa? In some cases, like Lee Myung-bak's early attempt to ratify GSOMIA, it seems like the overwhelming public outrage was the main obstacle to forward progress. In other cases, like the National Assembly debates surrounding the 2019 trade dispute, there are indications of a political calculus behind rising tensions. Like the snake eating its own tail, it could be that political elites and civil society feed off of each other in a cycle that neither one can fully control or escape.

The interaction between anti-Japan and anti-communist pressures in modern South Korea is crucial to understanding both its persistently high mobilization on Japan issues and the complicated sentiments at play beneath its seemingly robust liberal democracy. Undeniably, Koreans have reason to feel resentment over the abuses of the colonial past and Japan's sometimes less-than-contrite behavior. But it is important to recognize that their continued high mobilization on these issues is not always driven by Japan's actions. In today's South Korea, the free expression of anti-Japanese sentiment and demands for postcolonial atonement are inextricably linked with the rejection of dictatorship, the dissemination of democratic norms of free speech and civil rights, equitable redistribution of wealth and privilege, and all that South Korea has achieved politically since 1987. Regrettably, this has come to mean that an uncompromising stance on Japan issues is considered part of being a “good” progressive. Progressive civil society further inflames political rhetoric, wielding the “chinil” label as a cudgel and creating incentives for leftist politicians to push an ever-harder line toward Japan, just as right-wing societal actors and media wield the powerful “pro-North” cudgel against progressives.