Evidence from early studies of first-episode schizophrenia suggested that a longer period of unchecked, untreated illness was associated with a poorer prognosis. Reference Crow, MacMillan, Johnson and Johnstone1–Reference Szymanski, Lieberman, Alvir, Mayerhoff, Loebel, Geisler, Chakos, Koreen, Jody and Kane3 This association has been supported in some further studies, Reference Larsen, McGlashan and Moe4–Reference Wunderink, Nienhuis, Sytema and Wiersma9 but not all. Reference Craig, Bromet, Fennig, Tanenberg-Karant, Lavelle and Galambos10–Reference Verdoux, Liraud, Bergey, Assens, Abalan and van Os12 However, two systematic reviews concluded that whereas a longer duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) is associated with a worse response to antipsychotic medication in the first year of treatment in terms of positive and negative symptoms, the relationship with social function is less consistent. Reference Marshall, Lewis, Lockwood, Drake, Jones and Croudace13,Reference Perkins, Gu, Boteva and Lieberman14 There are limited data on the relationship between DUP and cognitive function at baseline or after a period of treatment with antipsychotic medication, but few of the relevant studies have found any association. Reference Perkins, Gu, Boteva and Lieberman14,Reference Rund, Melle, Friis, Larsen, Midbøe, Opjordsmoen, Simonsen, Vaglum and McGlashan15

Several studies indicate that social functioning in people with psychosis is correlated with a number of concomitant factors, including positive and negative symptoms, disorganisation syndrome and cognitive functioning. Reference Breier, Schreiber, Dyer and Pickar16–Reference Green18 Since all of these aspects of functioning have been purported to be worse in people with a longer DUP, this raises the question of whether the relationship between DUP and outcome is a direct causal one or rather the result of an association between symptoms and/or cognitive functioning and social functioning at the same time point – a mediated relationship. As DUP is potentially a prognostic factor open to intervention, previous work has tried to determine whether its association with poorer outcome represents a causal relationship or whether it is an epiphenomenon, with a common underlying factor, such as poor premorbid function or insidious onset of illness. Reference Verdoux, Liraud, Bergey, Assens, Abalan and van Os12,Reference Barnes, Hutton, Chapman, Mutsatsa, Puri and Joyce19 This study explores a related aspect: which outcome factors are directly linked with DUP. Greater understanding of this might help to explain the result of any intervention aimed at reducing DUP.

In the West London First Episode Schizophrenia Study we investigated prospectively a sample of people presenting for the first time with schizophrenia and assessed the influence of DUP on 1-year outcome. Measures of outcome were positive, negative and disorganisation syndromes, social function and cognition. Based on previous research, our hypothesis was that longer DUP would predict increased symptoms and worse social functioning but not cognitive functioning at follow-up. We also predicted that the effect of DUP on social functioning at follow-up would be mediated via symptoms at the same time point and that there would be no direct relationship between DUP and social function at follow-up once this indirect relationship was taken into account.

Method

Sample

Individuals recruited into the prospective West London First Episode Schizophrenia Study (n=135) received clinical and neuropsychological assessments at initial presentation. Reference Hutton, Puri, Duncan, Robbins, Barnes and Joyce20 Inclusion criteria were that an individual was experiencing his or her first episode of psychosis, had been prescribed antipsychotic medication for less than 12 weeks, fulfilled DSM–IV criteria for schizophrenia (n=97) or schizoaffective disorder (n=1), 21 was aged 16–55 years and had a command of English sufficient to participate in the range of assessments.

Assessments

Duration of untreated psychosis and of untreated illness

The dates of onset of prodromal and psychotic symptoms were elicited as previously reported, Reference Barnes, Hutton, Chapman, Mutsatsa, Puri and Joyce19 with sources of information including patient interview, clinical case-notes and questioning of the relatives and carers. Duration of untreated psychosis was calculated as the time from onset of psychotic symptoms to first treatment with antipsychotic medication. Duration of untreated illness (DUI) was calculated as DUP plus any prodromal period.

Participants were assessed at the time of their first presentation to psychiatric services, and subsequently at 1-year follow-up, using the same measures, described below.

Mental state

The participants' mental state was assessed with the Scale for Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) and the Scale for Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS). Reference Andreasen22 Three symptom-derived syndrome scores were derived: Reference Liddle and Barnes23,Reference Gur, Petty, Turetsky and Gur24 positive syndrome (SAPS hallucinations and delusions), disorganisation syndrome (SAPS bizarre behaviour and positive formal thought disorder) and negative syndrome (all SANS sub-scales), as well as a score for the ‘core’ negative symptoms of flat affect and poverty of speech (SANS sub-scale scores for affective flattening and alogia). Reference Liddle25,Reference Möller, van Praag, Aufdembrinke, Bailey, Barnes, Beck, Bentsen, Eich, Farrow, Fleischhacker, Gerlach, Grafford, Heutschel, Hertkorn, Heylen, Lecrubier, Leonard, McKenna, Maier, Pedersen, Rappard, Rein, Ryan, Nielsen, Stieglitz, Wegener and Wilson26

Cognition

At initial assessment, premorbid IQ was estimated using the National Adult Reading Test (revised version). Reference Nelson27 Measures of neuropsychological function were obtained at both baseline and follow-up using a 4-sub-test, short form of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised (WAIS–R) and the Cambridge Automated Neuropsychological Test Battery (CANTAB). Reference Wechsler28,Reference Sahakian and Owen29 From the CANTAB, executive function (Tower of London planning, attentional set shifting and spatial working memory) and memory (spatial span and pattern recognition memory) tasks were employed.

Social function

Social function and re-integration into the community were assessed using the Social Function Scale (SFS). This is a 79-item, self-report scale, which Birchwood et al showed to be a reliable, valid and sensitive measure of social functioning in individuals with schizophrenia. Reference Birchwood, Smith, Cochrane and Wetton30 Individuals rate their abilities in seven areas: activation–engagement, interpersonal communication, frequency of activities of daily living, competence at activities of daily living, participation in social activities, participation in recreational activities, and employment/occupational activity.

Statistical analysis

Data were initially analysed using SPSS version 14 for Windows. To examine group differences, t-tests were used for continuous data and chi-squared tests for categorical data. Linear regressions were used to examine effect of DUP on 1-year outcome. Mplus (version 5; www.statmodel.com) path analysis was used to investigate the relationship between DUP and the follow-up scores for the positive syndrome, negative syndrome and social function scores.

Results

Of the 135 patients who received clinical and neuropsychological assessments at initial presentation, 98 (73%) were re-assessed approximately 1 year later (median follow-up period 383 days). When the group of participants lost to follow-up were compared with those who were assessed at follow-up on the demographic, clinical and IQ measures at initial presentation, there was no significant difference on any measure (age at onset, t 133=0.15; age at testing, t 133=0.58; negative syndrome, t 133=1.53; positive syndrome, t 133=0.97; disorganisation syndrome, t 133=0.92; DUP, t 133=1.47; National Adult Reading Test premorbid IQ, t 122=0.58; WAIS–R current IQ, t 124=1.32; medication, χ2=0.47; gender, χ2=0.53; all NS).

For the 98 participants re-assessed at 1 year the median value for DUP was 20 weeks and the mean was 52.5 weeks (s.d.=82.6). In 13 individuals no accurate estimate of DUI was possible, and data for these cases were therefore excluded from any analyses relating to DUI. The median DUI for the remaining 85 patients was 104 weeks and the mean was 188.9 (s.d.=248.1). For analysis using parametric statistics, both DUP and DUI scores were log10 transformed because of positive data skewness. Table 1 shows the correlations between both log10 DUP and log10 DUI for the clinical outcome measures at follow-up. Given the lack of significant correlations between DUI and syndrome scores and also overall social function, DUI was not included in further analyses.

Table 1 Pearson correlation coefficients between log10 duration of untreated illness, log10 duration of untreated psychosis, and symptom syndrome scores and social function assessed at 1-year follow-up

| Log10 DUP | Log10 DUI | |

|---|---|---|

| Negative syndrome | 0.260** | 0.114 |

| Positive syndrome | 0.284** | 0.109 |

| Disorganisation syndrome | 0.056 | -0.068 |

| Social Function Scale | ||

| Total score | -0.312** | -0.166 |

| Activation—engagement | -0.335** | -0.197 |

| Interpersonal communication | -0.180* | -0.126 |

| Frequency of activities of daily living | -0.218* | -0.042 |

| Competence at activities of daily living | -0.110 | 0.055 |

| Participation in recreational activities | -0.113 | -0.036 |

| Participation in social activities | -0.256* | -0.284** |

| Employment/occupation activity | -0.301** | -0.186 |

In the initial exploration of the data, the sample was dichotomised into those with a short or long DUP, using a median split, Reference Verdoux, Liraud, Bergey, Assens, Abalan and van Os12,Reference Perkins, Lieberman, Gu, Tohen, McEvoy, Green, Zipursky, Strakowski, Sharma, Kahn, Gur and Tollefson31 although later analyses used DUP as a continuous measure. These two groups did not significantly differ on measures which, based on a priori expectations from previously published studies, could be considered a significant predictor of outcome (age at onset, t 96=0.62; premorbid IQ, t 90=0.44; gender, χ2=0.65; follow-up period, t 96=0.60; all NS).

There was no significant difference between short and long DUP groups on SFS total score, positive, negative and disorganisation syndromes scores and core negative symptoms at initial presentation (Table 2). At 1 year significant differences were found for negative and positive syndrome scores and total SFS score (Table 2). When the SFS sub-scales were examined there were significant differences for activation–engagement, frequency of activities of daily living, participation in social activities and employment/occupation activity.

Table 2 Clinical and key outcome variables at baseline and follow-up

| Initial presentation | 1-year follow-up | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | DUP ≤20 weeks | DUP >20 weeks | Statistical test | DUP ≤20 weeks | DUP >20 weeks | Statistical test |

| Participants, n | 52 | 46 | ||||

| Follow-up period, days: mean (s.d.) | 518 (338) | 564 (426) | ||||

| DUP, weeks: mean (s.d.) | 7.3 (5.9) | 106.7 (106.4) | ||||

| Type of medication, n | ||||||

| 1. Drug free | 3 | 7 | 8 | 5 | ||

| 2. First-generation antipsychotic | 27 | 18 | (excluding group 4) | 19 | 16 | (excluding group 4) |

| 3. Second-generation antipsychotic | 21 | 18 | χ2=2.97, d.f.=2, NS | 25 | 25 | χ2=0.58, d.f.=2, NS |

| 4. Combined first- and second-generation antipsychotics | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Negative syndrome score: mean (s.d.) | 0.41 (0.27) | 0.39 (0.27) | t 96=0.33, NS, d=0.07 | 0.21 (0.22) | 0.32 (0.23) | t 94=2.31, P=0.023, d=0.48 |

| Positive syndrome score: mean (s.d.) | 0.70 (0.26) | 0.66 (0.27) | t 96=0.73, NS, d=0.15 | 0.17 (0.25) | 0.29 (0.32) | t 94=2.04, P=0.044, d=0.41 |

| Disorganisation syndrome score: mean (s.d.) | 0.43 (0.29) | 0.35 (0.28) | t 96=1.25, NS, d=0.28 | 0.06 (0.15) | 0.06 (0.13) | t 94=0.001, NS, d=0.0 |

| Overall SFS score: mean (s.d.) | 111.76 (13.98) | 108.10 (11.73) | t 86=1.32, NS, d=0.28 | 115.2 (8.9) | 108.2 (12.7) | t 91=3.07, P=0.003, d=0.62 |

| SFS sub-scale (scaled) score: mean (s.d.) | ||||||

| Activation—engagement | 99.16 (13.30) | 100.49 (14.40) | t 86=0.45, NS, d=0.09 | 107.74 (12.50) | 99.78 (11.67) | t 93=3.20, P=0.002, d=0.62 |

| Interpersonal communication | 112.89 (23.98) | 110.02 (22.08) | t 86=0.58, NS, d=0.12 | 120.12 (18.65) | 114.20 (21.18) | t 93= 1.44, NS, d=0.30 |

| Frequency of activities of daily living | 114.65 (19.21) | 108.24 (21.54) | t 86=1.47, NS, d=0.31 | 116.30 (14.42) | 108.99 (18.36) | t 93= 2.17, P=0.033, d=0.44 |

| Competence at activities of daily living | 115.75 (17.03) | 113.81 (11.97) | t 86=0.61, NS, d=0.13 | 116.01 (11.92) | 114.06 (13.67) | t 93= 0.75, NS, d=0.15 |

| Participation in recreational activities | 113.14 (20.47) | 108.62 (18.63) | t 86=1.08, NS, d=0.23 | 114.55 (17.04) | 109.39 (19.97) | t 93= 1.36, NS, d=0.28 |

| Participation in social activities | 117.61 (17.67) | 110.26 (17.04) | t 86=1.97, P=0.052, d=0.42 | 120.36 (11.77) | 110.89 (20.72) | t 93= 2.77, P=0.007, d=0.55 |

| Employment/occupation activity | 110.92 (15.31) | 105.23 (13.73) | t 86=1.82, P=0.072, d=0.39 | 110.91 (11.78) | 101.74 (15.32) | t 93=3.28, P=0.001, d=0.64 |

To evaluate the extent to which DUP influenced these measures at 1 year, a series of stepped linear regressions were performed. Significant correlations were found between initial and 1-year scores for positive syndrome (r=0.33, P=0.001), negative syndrome (r=0.19, P=0.064) and SFS total score (r=0.40, P<0.001). Thus, for each outcome variable, the score at initial presentation was entered in the first step to control for the effect of baseline function on outcome, and the score at 1 year was entered as the second step. This approach allows any differences in follow-up scores to be confidently ascribed to the effect of DUP on outcome, independent of functioning at first presentation. Duration of untreated psychosis was a significant predictor of the outcome in each case (positive syndrome: F change=7.06, P=0.009, r 2=0.06; negative syndrome: F change=9.39, P=0.003, r 2=0.09; SFS overall score: F change=7.36, P=0.008, r 2=0.07).

Between 90 and 95 participants completed each neuropsychological test. Independent samples t-tests for current IQ and all continuous cognitive variables (spatial span, spatial working memory strategy and error scores, pattern recognition memory and Tower of London perfect solutions) revealed that there was no significant difference between the short and long DUP groups on any of these measures at either baseline or follow-up (range of t-test values at baseline 0.15–1.70; range at follow-up 0.25–1.34). Chi-squared analysis confirmed that there was no significant interaction between DUP and passing or failing the attentional set-shifting task at initial presentation (χ2=0.82, NS) or follow up (χ2=1.05, NS).

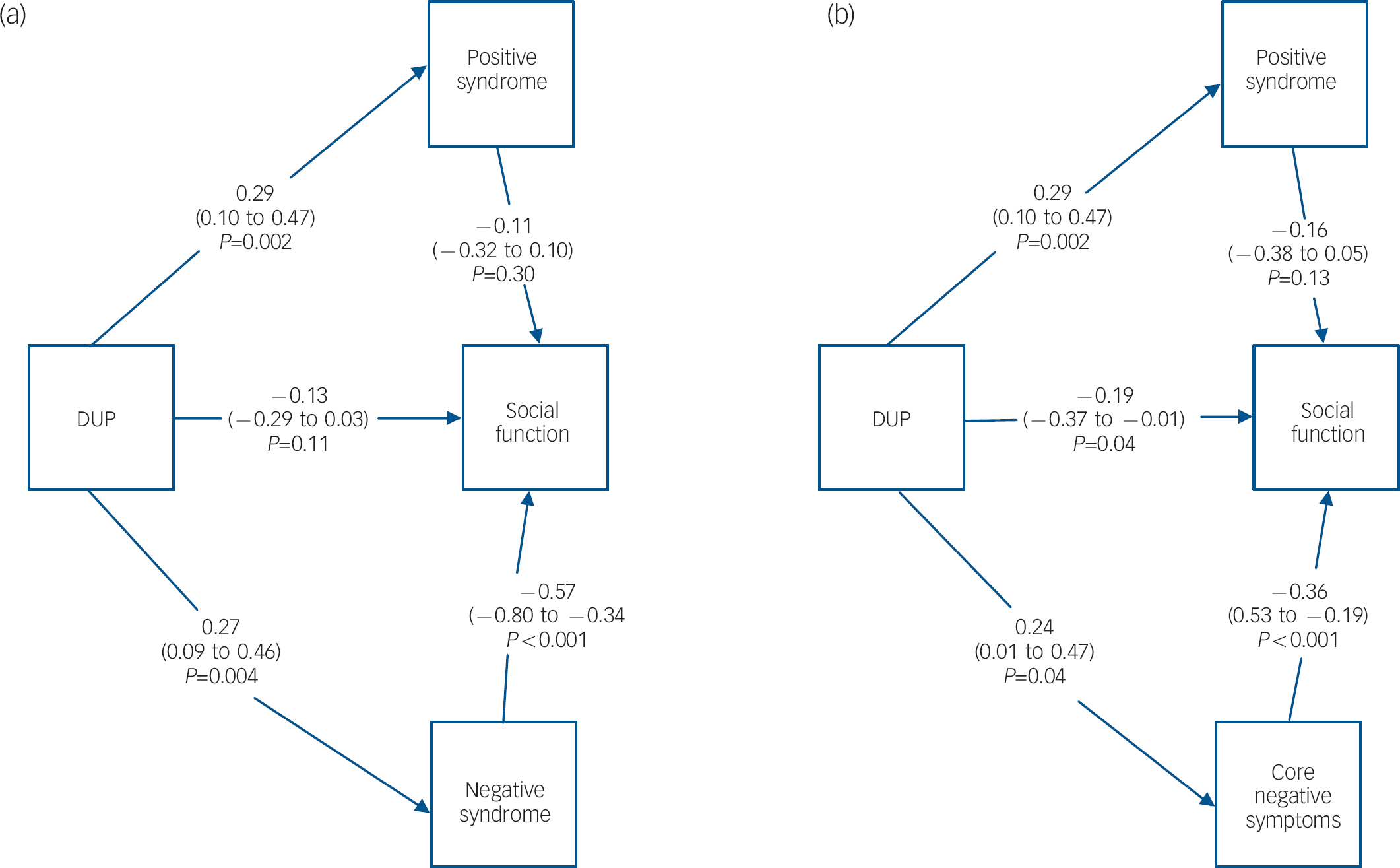

Path analysis

To determine whether the relationship between DUP and social function at 1-year follow-up was mediated by 1-year positive and/or negative syndrome scores, a path analysis was performed (model 1). We repeated the analysis substituting the core negative symptoms, SANS affective flattening and alogia for the negative syndrome score derived from the whole SANS scale (model 2). The core negative symptoms scores are not anchored with items of self-care and occupational and social functioning, which may reflect outcome instead of actual symptoms. Reference Barnes and Liddle32 This allowed delineation of the effect of social relationships and recreational activities potentially covered by both the SFS and SANS (e.g. ability to enjoy activities and relationship with friends/peers).

Although DUP was log-transformed to give an approximately normal distribution, it was not possible to transform the other variables (negative syndrome, positive syndrome and core negative symptoms) into the normal distribution, therefore we used bootstrap confidence intervals to allow for this.

Model 1 (incorporating the negative syndrome)

Results showed that a large component (39% of the explained variance in social function) of the effect was a direct effect of DUP on social function, although this did not achieve statistical significance (P=0.11). The DUP had a large and significant effect on positive syndrome score (P=0.002) but the positive syndrome score had no effect on social function score (P=0.30). Thus, the pathway from DUP to social function via positive syndrome was not significant and only accounted for 2% of the explained variance (r=–0.03; P=0.35). Note that the effect size via an indirect pathway is obtained by multiplying the effect sizes of each component part of that pathway. For example, the effect size of DUP on social function via positive syndrome is −0.03 (0.29×–0.11). Duration of untreated psychosis had a significant effect on the negative syndrome score (P=0.004) and negative syndrome score also had a significant effect on social function score (P<0.0001). This resulted in the pathway from DUP to social function via negative syndrome being significant, accounting for 59% of the explained variance in social function (r=–0.16, P=0.02) (Fig. 1).

There is strong evidence that these pathways collectively explain a significant amount of the variation in social functioning (χ2(6)=74.03, P<0.0001), and the goodness-of-fit chi-squared parameter suggests that there is only a modest amount of remaining variation to be explained (χ2(1)=5.39, P=0.02). However, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) statistic (0.218, 90% CI 0.069–0.413) suggests that a modest proportion of the variance remains unexplained by this model, and therefore other variables that are not included in the model may also affect social functioning at follow-up.

Model 2 (incorporating core negative symptoms)

A large, significant component of the effect was direct from DUP to social function score, accounting for 78% of the explained variance in social function in this model (r=–0.19, P=0.04). Duration of untreated psychosis had a large and significant effect on positive syndrome score (P=0.002), but the effect of positive syndrome score on social function score was not significant (P=0.13). Thus, the pathway from DUP to social function via positive syndrome was not significant and accounted for only 5% of the explained variance (r=–0.05, P=0.19). Duration of untreated psychosis had a significant effect on core negative symptom score (P=0.04) and core negative symptom score also had a significant effect on social function score (P<0.0001). This resulted in the pathway from DUP to social function via core negative symptoms accounting for 17% of the explained variance, although this failed to reach significance (r=–0.09, P=0.10). Again, there is strong evidence that these pathways collectively explain a significant amount of the variation in social functioning (χ2(6)=51.70, P<0.0001), and the goodness-of-fit chi-squared parameter suggests that there is no appreciable remaining variation to be explained (χ2(1)=2.36, P=0.12). However, once again the RMSEA statistic (0.122, 90% CI 0.000–0.333) suggests that other variables may also affect social functioning at follow-up.

Fig. 1 Model 1 (a) showing results from path analysis incorporating negative syndrome, with bootstrap correction for non-normality. Model 2 (b) showing results from path analysis incorporating core negative symptoms, with bootstrap correction for non-normality. For both models, the results show the standardised regression coefficients (equivalent to correlation coefficients) for the different arms, with associated 95% confidence intervals and P-values. DUP, duration of untreated psychosis.

Discussion

We found that a longer DUP was related to a greater severity of positive and negative symptoms and poorer social function 1 year after the start of antipsychotic treatment, and that this was independent of age at onset of psychosis and the severity of symptoms and social function at initial presentation. When we used path analysis to assess the interdependence of these relationships we found that DUP was directly and independently related to residual positive and negative symptoms. However, the effect of DUP on social function was more complex. Although this was independent of the DUP effect on positive symptoms, the possibility of a mediating effect of negative symptoms on social function depended on whether a narrow or broad concept of the negative syndrome was employed.

Duration of untreated psychosis and symptoms

We failed to find any significant association between longer DUP and more severe positive and negative symptoms on first admission. Reference Barnes, Hutton, Chapman, Mutsatsa, Puri and Joyce19 Similar findings have been reported, Reference Üçok, Polat, Genç, Cakir and Turan33 although several previous studies of first-episode psychosis have found such an association. Reference Larsen, McGlashan and Moe4,Reference Üçok, Polat, Genç, Cakir and Turan33,Reference Drake, Haley, Akhtar and Lewis34 One possible explanation for the failure to observe such a relationship at first episode is that for most people in the sample the presentation to psychiatric services is likely to have been prompted by reaching a threshold level of severity of symptoms, thus obscuring any relationship with DUP.

Studies of the relationship between DUP and symptoms following a period of treatment have also yielded inconsistent findings. Whereas most longitudinal first-episode studies have found that a longer DUP predicts more severe and enduring positive symptoms, Reference Malla, Norman, Manchanda, Ahmed, Scholten, Harricharan, Cortese and Takhar6–Reference Addington, van Mastrigt and Addington8 a positive association between DUP and negative symptoms has been found in some studies, Reference Harrigan, McGorry and Krstev7,Reference McGorry, Edwards, Mihalopolous, Harrigan and Jackson36–Reference Malla, Norman, Takhar, Townsend, Scholten and Haricharan38 but not in others. Reference Addington, van Mastrigt and Addington8,Reference Craig, Bromet, Fennig, Tanenberg-Karant, Lavelle and Galambos10,Reference Larsen, Moe, Vibe-Hansen and Johannessen39 The variability in findings may partly reflect differences in the relationship between DUP and negative symptoms between subgroups of patients with first-episode disorder. Reference Schmitz, Malla, Norman, Archie and Zipursky40 Another potential explanation concerns the measures used to assess the negative syndrome. Thus, in this study when we used a negative syndrome score derived from all sub-scales of the SANS, we found a stronger relationship with DUP than when we used only core negative symptoms in the analysis.

Although Addington et al failed to find an association between DUP and negative symptoms, they speculated that when such an association is reported it may reflect either that negative symptoms pre-date onset and hinder help-seeking or that longer DUP itself leads to enduring negative symptoms. Reference Addington, van Mastrigt and Addington8 Against the former explanation of our results is that DUP remained a significant predictor of follow-up symptom scores when controlling for the influence of the respective baseline symptom scores, suggesting that DUP is influencing outcome over the initial year of treatment. Supporting this conclusion is the finding of an association between DUP and enduring negative symptoms by Edwards et al even after they had controlled for premorbid function. Reference Edwards, Harrigan, McGorry and Amminger41

Duration of untreated psychosis and social function

As with negative symptoms, the evidence for a relationship between longer DUP and indices of poorer social and occupational functioning following treatment is inconsistent. Reference Perkins, Gu, Boteva and Lieberman14,Reference Norman, Lewis and Marshall42 Again, this may reflect the different measures employed. In our study, social function and re-integration into the community were assessed using the SFS, which was specifically designed to evaluate social function in people with schizophrenia. Reference Birchwood, Smith, Cochrane and Wetton30 We found that a longer DUP was associated with poorer overall social function at follow-up, which was largely a reflection of significantly poorer social engagement and a lower frequency of activities of daily living, as well as less participation in social activities and lack of employment or occupation. When we examined whether poorer social function at 1-year follow-up was mediated by the effects of DUP on positive and negative symptoms, using a path analysis, we found that the relationship between DUP and social function was unambiguously independent of positive symptoms. The relationship between DUP, negative symptoms and social function, on the other hand, depended on whether SANS general or core negative symptoms were used in the analysis. When the full range of SANS negative symptoms was used, the relationship between longer DUP and poor social function was largely mediated via the negative syndrome, reflecting 59% of the variance. When the analysis was repeated using only core negative symptoms, the relationship between longer DUP and poor social function was not mediated via the negative syndrome and instead, a major part of the variance (78%) was explained by the direct effect of DUP on social function.

The measure of core negative symptoms adopted in this study assessed the severity of flatness of affect and poverty of speech using the alogia and affective flattening sub-scales of the SANS. Reference Liddle25,Reference Möller, van Praag, Aufdembrinke, Bailey, Barnes, Beck, Bentsen, Eich, Farrow, Fleischhacker, Gerlach, Grafford, Heutschel, Hertkorn, Heylen, Lecrubier, Leonard, McKenna, Maier, Pedersen, Rappard, Rein, Ryan, Nielsen, Stieglitz, Wegener and Wilson26 The remaining SANS sub-scale measures of avolition, anhedonia and attentional impairment were excluded because they contain items assessing self-care and occupational and social functioning, which arguably reflect social function rather than symptoms intrinsic to the disorder. Reference Barnes and Liddle32 This method therefore allowed a delineation of the effect of DUP on social relationships and recreational activities potentially covered by both the SFS and SANS scales. The difference in our findings when narrow and broad concepts of the negative syndrome were used probably reflects the phenomenological overlap between the two scales. Reference Barnes and Liddle32,Reference Peralta and Cuesta43 What is clearly demonstrated by these two contrasting models is how fundamentally important the conceptualisation of these overlapping elements is when analysing and interpreting the relationship between DUP and outcome.

Duration of untreated psychosis and cognition

We found no evidence of any significant difference in global IQ or performance on a range of cognitive tests between those with short and long DUP at either initial presentation or follow-up. We have previously reported that in the same baseline sample, assessed at first presentation, longer DUP was related to impaired performance on the attentional set-shifting task but to no other neuropsychological measure. Reference Joyce, Hutton, Mutsatsa, Gibbins, Webb, Paul, Robbins and Barnes44 The disparity between these results may reflect differences in the definition used for success on the attentional set-shifting task. In the study reported here, participants were dichotomised into those passing and failing the task, and this required completion of all nine stages. In the earlier study we examined the stage reached, and, of the participants who did not reach stage nine, it is possible that, on average, those with a short DUP progressed to a later stage than those with a longer duration. Reference Joyce, Hutton, Mutsatsa, Gibbins, Webb, Paul, Robbins and Barnes44 However, the results of both studies suggest that DUP does not broadly affect cognition. Further, the current findings are consistent with other longitudinal first-episode studies which have failed to find a relationship between DUP and cognitive function. Reference Addington, van Mastrigt and Addington8,Reference Hoff, Sakuma, Heydebrand, Heydebrand, Csernansky and DeLisi45–Reference Ho, Alicata, Ward, Moser, O'Leary, Arndt and Andreasen47 Although cognitive impairment may be a risk factor for the onset of psychosis, Reference Joyce, Hutton, Mutsatsa and Barnes48 our findings suggest that cognitive function does not mediate the relationship between DUP and the outcomes we examined.

Implications of the findings

One hypothesis put forward to explain the association between longer DUP and a worse outcome in terms of psychotic symptoms is that there is an active morbid process with unchecked psychosis, which may be slowed or attenuated by treatment with antipsychotic medication. Reference Wyatt49 Keshavan et al reported that longer DUP is associated with a decrease in superior temporal gyral volume, Reference Keshavan, Haas, Kahn, Aguilar, Dick, Schooler, Sweeney and Pettegrew50 and more recently Lappin et al found that temporal grey-matter reductions were more marked in patients with long DUP. Reference Lappin, Morgan, Morgan, Hutchison, Chitnis, Suckling, Fearon, McGuire, Jones, Leff, Murray and Dazzan51 These findings may reflect a progressive pathological process that is active prior to treatment, Reference DeLisi, Sakuma, Tew, Kushner, Hoff and Grimson52 and if antipsychotic treatment delays or prevents the structural brain changes associated with psychosis, Reference Keefe, Seidman, Christensen, Hamer, Sharma, Sitskoorn, Lewine, Yurgelun-Todd, Gur, Tohen, Tollefson, Sanger and Lieberman53 increased neuronal damage would be associated with greater DUP. Although the exact underlying mechanism remains to be determined, it is plausible that this neuronal damage impedes treatment response and, specifically, symptom reduction with antipsychotic medication, resulting in the greater residual positive and negative symptoms found in patients with longer DUP both in this study and elsewhere. Reference Malla, Norman, Manchanda, Ahmed, Scholten, Harricharan, Cortese and Takhar6,Reference Harrigan, McGorry and Krstev7 However, the direct effect of DUP on social function, revealed by specifically excluding negative symptoms that partly reflect social function, cannot be so easily explained as a direct result of neuronal damage, since social function is arguably even more removed than clinical symptoms from the pathophysiological basis of the illness. Rather, this finding suggests that important factors other than symptoms mediate the effect of DUP on social function, with social perception and social knowledge being likely candidates. Reference Addington, Saeedi and Addington54,Reference Brekke, Hoe, Long and Green55

In summary, our findings suggest that longer DUP has predictive value for poorer clinical and social outcome in schizophrenia in respect of persistent symptoms and social re-integration that is independent of age, age at onset of psychosis and the clinical ratings of these outcome domains at first presentation to services. They also have implications for the interpretation of the results of previous first-episode studies reporting the relationship between DUP, and the level of social function and severity of negative symptoms following a period of treatment. Certain elements relevant to social function, such as self-care, work function and interpersonal relationships, are common to measures of these two domains, and thus there is the potential for confounding of their association with DUP. However, our results provide evidence for a direct relationship between DUP and social function when this overlap is addressed.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by a Wellcome Trust programme grant (064607). We acknowledge the help of Mrs I. Harrison, Dr B. Puri and Dr M. Chapman with data collection.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.