Discussion and debate lie at the heart of democratic politics. When communicating with the public, politicians make use of a wide range of argumentation strategies, such as empathetic appeals, emotional arguments and aggressive attacks. What politicians say and, importantly, how they say it matter a great deal. While politicians expressing empathy, emotion and aggression is unremarkable, certain politicians may face harsher penalties than others when they express, or do not express, these styles. Former UK Prime Minister Theresa May was known for a style that was characterized as unemotional, unempathetic and robotic. May's style received significant press commentary, with some asking ‘“what is wrong” with her’ (The Independent 2017a), and others branding her as ‘inhuman and uncaring’ (The Independent 2017b) or suggesting that her ‘inability to show emotion to the public proves that she isn't fit to be prime minister’ (The Independent 2017a). In the eyes of the public too, May was seen as having a ‘cold personality’ (YouGov 2017). This led to her infamous characterization in the press and across social media as ‘the Maybot’ (The Spectator 2017). Yet, when her resignation speech was uncharacteristically marked with emotion and tears, it prompted some to bid farewell to a leader who was ‘almost human after all’ (The Independent 2019).

Theresa May's style is one that goes against what is stereotypically expected of women in politics (Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2019), and she has been branded as inhuman, cold and robotic as a result. While this anecdote illustrates only one example of how the styles of women are evaluated, there is ample evidence that women politicians more broadly incur penalties when they do not conform to stereotype-congruent behaviours (Bauer Reference Bauer2015a; Boussalis et al. Reference Boussalis2021; Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2018). Men politicians, by contrast, have been shown to be successful both when they conform to stereotype-expected behaviours – such as being ambitious (Saha and Weeks Reference Saha and Weeks2022) – and when they subvert expectations – such as being emotional or communal (Gleason Reference Gleason2020; Okimoto and Brescoll Reference Okimoto and Brescoll2010). Indeed, past work has shown there to be clear evidence of asymmetric standards in how men and women politicians are evaluated.

In this article, I assess whether voters are biased in their perceptions and evaluations of the ways in which politicians communicate, and, consequently, whether voters' evaluations of elite political communication are gendered. While there is a robust literature on the influence of gender stereotypes on voter evaluations in politics more broadly, scholars have so far neglected to unpack whether voters differentially perceive politicians' behaviour based on gender alone. This article makes an important contribution by being the first to address this question and to assess whether the differential perception of styles themselves may serve as a potential mechanism through which voters' gendered evaluations of politicians become manifest.

To test these questions, I focus on styles for which the gender-stereotypes literature has outlined clear expectations about men's and women's behaviour. Work to date examining how voters evaluate stereotype-(in)congruent behaviour has focused on isolated traits (for example, Bauer Reference Bauer2015a; Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2018). Instead, while I analyse the effect of each style separately, I make progress by focusing on how voters evaluate politicians' use of a diversity of styles that are consistent with both feminine ‘communal’ and masculine ‘agentic’ stereotypes (Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2019). By doing so, I assess whether there are asymmetric standards in the degree to which men and women politicians are punished for stereotype-incongruent behaviours. I focus on the use of emotion, aggression and evidence (both drawing on statistical and anecdotal evidence). In a novel survey experiment, I present UK voters with speeches where the argument style and the gender of the politician delivering the argument are varied. Through these manipulations, I assess, first, whether politicians incur negative evaluations from voters when they deploy styles that are stereotype-incongruent and, secondly, whether voters' differential perception of styles themselves might explain the backlash politicians receive.

I report four main findings. First, I find that politicians' style usage has important consequences for how voters evaluate them. Politicians are liked more when they are emotional or draw on anecdotes; however, they are regarded as more competent when they are unemotional and make use of statistical evidence. Secondly, contrary to expectations from the stereotypes literature, I find no evidence that these evaluations are gendered. That is to say, while all politicians are evaluated as less likeable when they are aggressive, there is no evidence that women in particular incur negative evaluations. Thirdly, while there is clear evidence that voters can identify the styles politicians use, I also find no evidence that voters' perceptions of the styles themselves are gendered. Voters do not perceive unemotional arguments by women as any less emotional than unemotional arguments by men, nor do they perceive aggressive arguments by women to be any more aggressive than equally aggressive arguments by men. Fourthly, I find some evidence that these evaluations differ by voter gender. Women voters reward women politicians for stereotype-congruent behaviour: they give a larger likeability and competence reward to women who are emotional, and perceive arguments by women to be more emotional.

The main finding I document is, therefore, that there is little evidence of gender bias in the forum I study. These findings do not, however, imply that there is no gender bias at play in politics. I study voter evaluations of the likeability and competence of politicians, as gendered and non-gendered accounts of leadership alike suggest that they are some of the key qualities expected of politicians (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke2018; Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993). However, even if voters equally evaluate men and women for the styles they use, I do not assess how likeability and competence may have downstream consequences for voting. Previous US-based work has suggested that competence evaluations may be more important in voters' evaluations of women (Ditonto Reference Ditonto2017) and, therefore, that women may need to be perceived as more competent than men to get elected. The media may also play an important role in the framing of women's behaviour. If the media frame women's behaviour in a more negative light than men's, this may, in turn, feed into how voters evaluate politicians even if voters' direct judgements are not themselves gendered. Finally, my results suggest that voters deem politicians to be less competent when they express styles traditionally associated with feminine ‘communal’ stereotypes (Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2019). Therefore, if the distribution of actual style usage is different for men and women, then this may still lead to bias. If it is true that women happen to make greater use of communal styles – such as emotion or anecdotes – than men, then they may incur negative competence evaluations simply because of the styles they use. Evidence from a variety of contexts has shown that women politicians are more emotional (Dietrich, Hayes and O'Brien Reference Dietrich, Hayes and O'Brien2019) and draw more on anecdotes (Hargrave and Langengen Reference Hargrave and Langengen2021), though recent work has shown that women have made decreasing use of these styles over time in the UK (Hargrave and Blumenau Reference Hargrave and Blumenau2022). In short, identifying the mechanism through which biases emerge in the judgement of politicians' behaviour is challenging, and I make an important contribution by shedding light on one crucial aspect of this complex process: whether voters' perceptions of and attitudes towards elite political communication are gendered.

A commonly held perception is that men's leadership styles are preferred for political office than are women's (Fox and Oxley Reference Fox and Oxley2003), and that when women try and adopt these styles, they violate feminine stereotypes and will lose out. However, the findings I present here suggest that the reality for women may be more positive than this, as the expectation that they must avoid these styles for fear of negative backlash from voters is somewhat misguided. Recent work has shown that discrimination can occur when individuals perceive that others are likely to discriminate and that voters tend to overestimate the degree to which others are biased (Bateson Reference Bateson2020). Documenting that voters may not be as biased towards stereotype-incongruent women is important, then, as it may potentially help to further reduce voter bias. While, of course, women may be sanctioned for stereotype-incongruent behaviour from other sources, the findings I present here suggest that voters do not punish women in the way common theories of gender stereotyping may have predicted.

Gender, Stereotypes and Voter Backlash

Why might voters hold different expectations for how men and women politicians behave? Gender role theory – a prominent psychological approach for explaining gender-based behavioural differences (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002) – suggests that stereotypes concerning the typical behaviours of men and women lead to strong expectations for how individuals of different genders will and should behave. The social roots of such gender roles are thought to emerge from a type of statistical profiling: to the extent that, for diverse historical reasons, women and men display different behaviours on average, people internalize these patterns and the ‘corresponding attributes become stereotypic of women [men] and part of the female [male] gender role’ (Eagly and Wood Reference Eagly and Wood2012, 11). These behaviours are not always precisely defined; however, they are broadly divided into women's ‘communal’ behaviours, which are associated with emotionality, positivity, warmth, human interest and caring for others, and men's ‘agentic’ behaviours, which are associated with aggression, logic and leadership (Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2019).

Over time, the expectation that men and women should behave in ways associated with their gender is reinforced through a process of socialization. Further, descriptive stereotypes, which purport to describe what group members are like, lead to prescriptive stereotypes, which purport to describe what group members should be like (Gill Reference Gill2004). The idea that women are, say, gentle and emotional eventually leads to the expectation that women should be gentle and emotional. Behaviour that is inconsistent with these stereotypes may then be punished via social sanctions imposed by others. The upshot is that gender roles become self-reinforcing, as societal beliefs about the typical behavioural differences lead to ever-more entrenched patterns of gendered behaviour.

I focus on four styles for which the gender-stereotypes literature outlines clear expectations for gendered usage. The first communal style is emotion. Women are expected to be more emotional (Dietrich, Hayes and O'Brien Reference Dietrich, Hayes and O'Brien2019; Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993), and more positive specifically (Hargrave and Blumenau Reference Hargrave and Blumenau2022). The second communal style is anecdotal evidence. Women are thought to make greater use of anecdotes, which includes referencing personal experience, analogies or stories (Childs Reference Childs2004; Hargrave and Langengen Reference Hargrave and Langengen2021). The first agentic style is the use of aggression. Men are thought to be more aggressive (Grey Reference Grey2002), whereas women are thought to avoid this behaviour for fear that it is ‘negatively perceived by the electorate’ (Childs Reference Childs2004, 190). The second agentic style is the use of statistical evidence (Mattei Reference Mattei1998), which is linked to the idea that men are thought to be more ‘analytical, organised and impersonal’ (Jamieson Reference Jamieson1995, 76).

How might the conformity to, or violation of, stereotype-congruent behaviours affect voter evaluations of politicians? Previous work has shown that women are subject to pressures to conform to stereotypes. When women express behaviours that are consistent with stereotypes of communality, they tend to be rewarded. Focusing on the behaviour of Angela Merkel, Boussalis et al. (Reference Boussalis2021) find that Merkel is rewarded by voters for displays of happiness but punished for expressions of anger. Similarly, work by Gleason (Reference Gleason2020) shows that women Supreme Court attorneys are successful when they use extensive emotional appeals. By contrast, when women express behaviours that are inconsistent with stereotypes of communality, they can incur backlash for it. For instance, Cassese and Holman (Reference Cassese and Holman2018) find that women candidates in particular are vulnerable to attacks when they use negative campaigning, though work by Brooks (Reference Brooks2011) finds that men and women candidates in the US are similarly penalized for their expressions of both anger and tears. How might these evaluations translate to men? Voters have been shown to be less sensitive to men expressing styles that are incongruent with masculine ‘agentic’ stereotypes (Gleason Reference Gleason2020), and, indeed, studies suggest that men are successful when they both follow and subvert gendered expectations (Okimoto and Brescoll Reference Okimoto and Brescoll2010).

I seek to identify whether politicians' use of stereotype-(in)congruent styles leads to differential voter evaluations. Previous work has focused on a diversity of traits that might be influenced by conformity to stereotypes (Brooks Reference Brooks2011; de Geus et al. Reference De Geus2021; Saha and Weeks Reference Saha and Weeks2022), which can be divided along two lines. The first is the extent to which politicians' conformity to stereotypes leads to voters feeling more warmly towards them as individuals. Women are expected to be communal, which includes being kind, caring and compassionate (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002). Therefore, when they behave in ways that are instead consistent with agentic stereotypes, such as being aggressive or ambitious, they fall short of expectations about the communal qualities deemed appropriate for women (Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2019). Studies assessing voter evaluations of role-incongruent women confirm that they are judged less favourably by voters (Boussalis et al. Reference Boussalis2021), whereas role-congruent women are regarded more favourably and rewarded via increased likeability evaluations (Bauer Reference Bauer2017).

Secondly, conformity to stereotype-congruent behaviours may also influence the extent to which voters judge politicians' ability to perform their jobs to a high standard. Politicians are expected to be competent, and as the traditional occupants of political leadership positions, men's competence in these roles is assumed in a way that women's is not (Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2019). Recent experimental work has shown that women overall may actually have a small electoral advantage relative to men (Schwarz and Coppock Reference Schwarz and Coppock2022) and that stereotypes about women's competence may have equalized in recent years (Donnelly et al. Reference Donnelly2016). Nonetheless, a large literature has shown that women have historically been evaluated as less competent (Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993) and that voters seek out more information about the qualifications of women than those of men (Ditonto Reference Ditonto2017). Consequently, I focus on both likeability and competence, which gendered and non-gendered accounts of leadership alike identify as some of the key qualities expected of politicians (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke2018; Huddy and Terkildsen Reference Huddy and Terkildsen1993). For both, I expect that women will be rewarded for expressing styles congruent with feminine ‘communal’ stereotypes and punished for expressing styles congruent with masculine ‘agentic’ stereotypes.

This study contributes to the literature discussed earlier in three key ways. First, work to date examining how voters evaluate stereotype-congruent or -incongruent behaviour has focused on isolated behaviours, such as tears (Brooks Reference Brooks2011) or negative attacks (Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2018). By contrast, while I analyse the effect of each style separately, I expand upon this to focus on how voters evaluate politicians' use of a diversity of styles that are consistent with both feminine ‘communal’ and masculine ‘agentic’ stereotypes. Therefore, I can identify whether women in particular incur penalties for stereotype-incongruent behaviour. Secondly, work on voter backlash has focused almost exclusively on the United States. While European work has studied gender bias in voting behaviour, with few exceptions (Saha and Weeks Reference Saha and Weeks2022), scholars have not assessed the influence that stereotypes might have on UK voters' evaluations. Thirdly, while there is a robust literature on the influence of stereotypes on voter evaluations in politics more broadly, scholars have so far neglected to unpack whether voters differentially perceive the behaviour of men and women, and whether differential perception of behaviour itself may, in turn, be responsible for how voters evaluate politicians. This study is the first to assess whether differential perceptions of styles themselves may serve as a potential mechanism through which voters' gendered evaluations of politicians might become manifest.

Differential Perceptions of Styles

What may explain why voters differentially penalize men and women for expressing styles that violate stereotypes? One mechanism through which these evaluations might become manifest is that – because of stereotypical expectations – voters simply perceive differently the styles that men and women use. That is to say, even in the absence of any objective differences in, say, the emotionality of a speech, voters ‘hear’ that speech as more or less emotional depending on the politician's gender. This differential perception of style may then, in turn, lead to voters' differential evaluation of the likeability or competence of men and women. Emotion is a style that is congruent with feminine communal stereotypes. Therefore, when women are not emotional, this may violate expectations about the supposed emotional sensitivity of women and be of particular note to voters. Since women are seen as particularly unemotional, they, relative to men, may be ascribed more negative evaluations and be seen as particularly ‘cold and unlikeable’.

Aggression is masculine stereotype-congruent. Therefore, when voters see a man delivering an aggressive speech, this may only serve to confirm pre-existing stereotypes. Stereotypical expectations dictate, however, that women are not expected to be aggressive. Voters may therefore pay more attention to aggressive women because this violates stereotypes. Since voters see a woman as particularly aggressive, this may, in turn, affect their likeability or competence evaluations of that woman. The experiences of former US presidential candidate Hillary Clinton – who was described as ‘too angry, aggressive, and unfeminine’ (Brooks Reference Brooks2013, 1) – may help to further explain this dynamic. Clinton may have been perceived as more aggressive than her men counterparts even when she may not actually have behaved in such as way because aggression is congruent with masculine stereotypes. Therefore, because Clinton's use of aggression is particularly noticeable, this may feed into her being evaluated more negatively.

There may also be differences in the degree to which voters perceive men's and women's use of anecdotes and statistics as evidence-based. While existing work has presented mixed conclusions about the persuasiveness of these evidence types, it is broadly concluded that statistical arguments help ensure argument credibility (Hornikx Reference Hornikx2018). As outlined earlier, studies have highlighted that men's competence is often assumed, while women's is not. Therefore, while I expect that arguments by all politicians will be perceived as more evidence-based when they contain statistics, arguments by women in particular will be perceived as more evidence-based when they include statistical evidence compared to anecdotal evidence. However, because of the assumed competence of men, the difference between anecdotal and statistical arguments delivered by men will be smaller. Therefore, I assess whether voters perceive men's and women's styles differently even in circumstances where there are no differences, and whether differential style perception may work as a mechanism for explaining variation in the likeability and competence evaluations that politicians receive.

Research Design

I test my expectations with a vignette survey experiment. In the experiment, respondents were tasked with reading an argument delivered by a fictitious politician. Respondents were randomly assigned to different treatment conditions where four attributes were randomized. The first attribute is the style of interest: emotion, aggression or evidence. The second attribute is the treatment status of the style: for emotion, the control condition is a neutral, non-emotional speech and the treatment condition is highly emotional; for aggression, the control condition is a neutral, non-aggressive speech and the treatment condition is highly aggressive; and for evidence, the control condition is statistical evidence and the treatment condition is anecdotal evidence.

The third attribute is the policy area: housing, health or transport. While I am not interested in making inferences about specific policies, I include several as there may be a concern that any effects uncovered for, say, women and emotionality on health may not translate to another area, such as transport. Work investigating the relative persuasiveness of different rhetorical techniques found there to be a large degree of heterogeneity in the persuasiveness of different rhetorical elements across policies (Blumenau and Lauderdale Reference Blumenau and Lauderdale2022). Therefore, by including a range of policies, I can average over them to address my central questions. Further, prior US-based work has highlighted that voters may make inferences about a politician's party based on the policy in question, as the Democrats have ‘ownership’ of particular issues, such as education, and the Republicans over others, such as defence (Petrocik, Benoit and Hansen Reference Petrocik, Benoit and Hansen2003). We may therefore be concerned that voters will evaluate politicians based on their perceptions of parties. In the UK, while certain issues are arguably associated with a particular party – for instance, welfare and the Labour Party (O'Grady Reference O'Grady2022) – I select housing, health and transport as issues that are central in British politics but not ‘owned’ by either party. Further, the treatments were written to reflect both Conservative and Labour priorities on the issue areas. For instance, the housing treatments include reference to areas that Labour champions, such as protecting vulnerable renters and the gaps between wages and house prices, and issues that the Conservatives have greater authority on, such as increasing homeownership. By doing so, I aim to minimize the likelihood that voters make inferences about a politician's party.

The fourth attribute is the gender of the MP: man or woman. Gender is delivered through fictional Anglo-Saxon names that represent the ‘typical’ politician. Previous experimental work has shown that changing name alone is a sufficient cue to induce voters' gendered attitudes (for a discussion, see Campbell and Cowley Reference Campbell and Cowley2014). In total, there are 3 × 2 × 3 × 2 (style × treatment status × policy area × gender) = 36 unique treatment conditions that serve as the basis of this experimental design (for all treatment texts, see the Online Appendix).

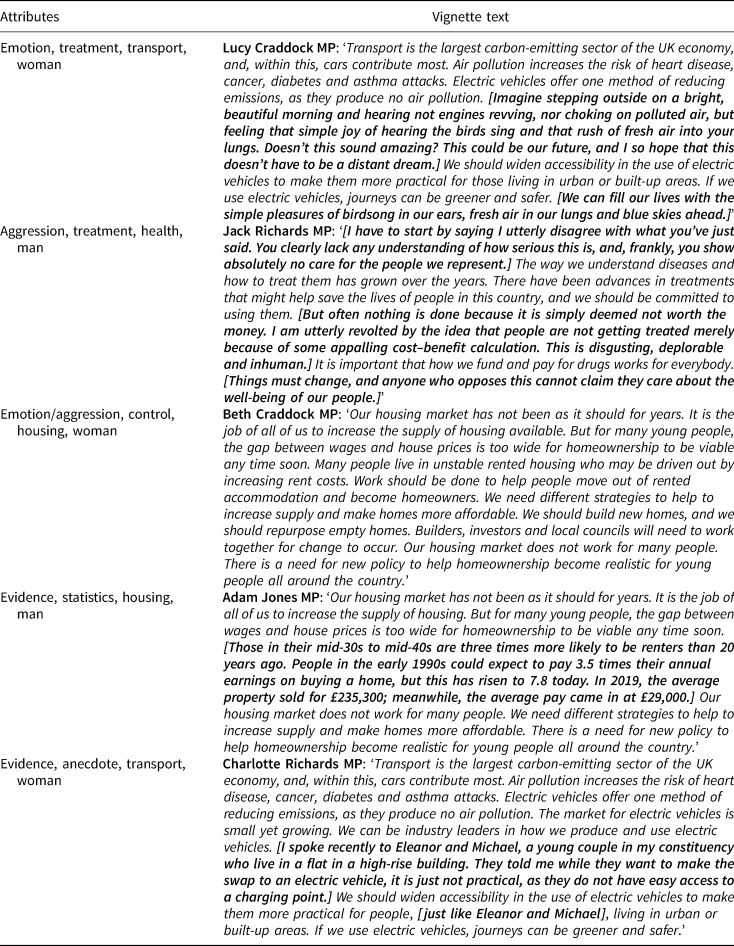

To ensure that the speeches are similar in spirit to the kinds of arguments politicians deliver in the UK parliamentary context, the speeches were informed by searching for debates on similar policy areas recorded in Hansard, the official report of parliamentary debates. When writing the speeches, the basic structure remained the same within a policy; however, I added words and sentences deemed representative of the style types.Footnote 1 For instance, a common approach for politicians delivering anecdotes is by referring to their constituents' experiences (Atkins and Finlayson Reference Atkins and Finlayson2013). As such, for the anecdote conditions, I refer to the same fictional constituency couple. Table 1 shows an example for each style, where the ‘treatment’ of the style is indicated in bold and square brackets.

Table 1. Vignette examples

To ensure I met these aims, I fielded a pre-test survey through Prolific to 1,500 members of their UK panel. The purpose was to ensure that the treatments were, and controls were not, considered representative of the styles. Overall, the results are encouraging: 72.5 per cent of respondents assigned the emotion treatment conditions (strongly) agreed that the treatments were emotional. Similarly, 67.7 per cent of respondents assigned the aggression treatment conditions (strongly) agreed that the treatments were aggressive. While most respondents perceived that both the statistics and anecdote speeches were evidence-based, a larger percentage of respondents perceived the statistical speeches as evidence-based (80.8 per cent and 56.8 per cent, respectively). Further, the pre-testing results provide good evidence that the controls were not perceived to be particularly representative of the style types. Only 18.3 per cent of respondents assigned to the emotion control conditions (strongly) agreed that the treatments were emotional. Additionally, 24.4 per cent of the respondents assigned to the aggression control conditions (strongly) agreed that the treatments were aggressive (for full details, see the Online Appendix).

I leverage parliamentary speeches as a forum where we might anticipate gender bias. There are, of course, alternative forums, such as politicians' campaign speeches or media descriptions of politicians' behaviour. Alternative channels of communication, such as media reporting, would enable me to assess only how gendered framing of politicians may influence voter judgements, not how voters may form judgements when they engage directly with politicians' speeches. While campaign speeches may seem the more natural forum through which politicians communicate with voters, previous work has highlighted that the single-member district electoral system in the UK provides MPs with an incentive to cultivate a personal vote (Kam Reference Kam2009). Further, work on UK parliamentary speech has shown that politicians make strategic use of this forum to appeal to voters (Blumenau Reference Blumenau2021; Osnabrügge, Hobolt and Rodon Reference Osnabrügge, Hobolt and Rodon2021). Therefore, in the UK, parliamentary speech is an appropriate forum to study my key questions of interest.

I focus on how voters judge politicians' use of stereotype-(in)congruent styles when they read arguments and am therefore unable to make statements about how such dynamics may differ when watching politicians. While a central part of style use is captured in the content of speech, tone and body language are important stylistic features. Boussalis et al. (Reference Boussalis2021) assess whether voters are biased in how they evaluate the styles of Angela Merkel through utilizing a variety of video, audio and text approaches. Their results – that Merkel is punished for aggressiveness and rewarded for happiness – hold across the different style measures but are most pronounced for non-verbal communication. By focusing on written speech, I may understate the extent to which voters are biased in their judgements. Presenting voters with speeches delivered in an audio or video format may, however, introduce unwanted confounders into the relationship – such as difficulties in holding tone, pitch or cadence constant – which would be challenging to account for. Instead, by focusing on written speech, I can hold constant all features except for politician gender and identify my key quantity of interest: whether a politician's gender alone influences voters' perceptions and evaluations.

A further source of concern may be that although the MP's party is not stated, voters may make inferences about party based on their gender. In the US, voters tend to stereotype the Democrats as more ‘feminine’ and the Republicans as more ‘masculine’ (Winter Reference Winter2010), and voters use a candidate's gender to infer candidate ideology (Koch Reference Koch2000). US-based experimental work has also emphasized the importance of partisanship in the degree to which voters stereotype politicians (Cassese and Holman Reference Cassese and Holman2018). In the US, therefore, voters have been shown to infer both that women are more liberal than men and that a candidate's partisanship determines the extent to which they incur negative evaluations. While I am unaware of work that has assessed this question directly in the UK, several factors suggest that this is perhaps less of a concern in my context. First, UK right-wing parties have made increasing efforts to integrate women numerically and to better represent women's interests (Childs and Celis Reference Childs and Celis2018). While Labour made earlier efforts to increase women's representation (Childs Reference Childs2004), the Conservatives have also made a concerted effort in recent years to ‘feminize’ the party by incorporating women into the party hierarchy and policy (Childs and Webb Reference Childs and Webb2012). Secondly, while Labour have proportionally more women legislators, the Conservatives have had two women prime ministers. Therefore, unlike in the US, the parties are more equal with respect to the visibility of women. Finally, recent work has also shown that while there are important differences with respect to party and gender stereotypes in the US, parties in the UK are less divided (Saha and Weeks Reference Saha and Weeks2022). Overall, gender equality is a less polarizing and party-political issue in the UK, and the British public has greater familiarity with the presence of women in both major parties. As such, while party is a critical factor with respect to gender and evaluations in the US, this is perhaps less of a concern in the UK political environment.

Survey

I use these treatments as the basis of a vignette survey experiment that was fielded by YouGov to their UK online panel in September 2021. I pre-registered the design, expectations and analysis plan.Footnote 2 The sample was 1,676 people who are nationally representative of the British public on a range of attitudinal and demographic criteria.

Following an introduction screen describing the task, respondents were presented with an argument delivered by a fictional politician. To encourage respondents to read the speech, there was a fifteen-second delay between the speech presentation and the first question. For a respondent's first task, a style was sampled from the full set of styles (emotion; aggression; evidence). For the selected style, a policy was sampled from the full set of areas (transport; housing; health). Within the policy area, a treatment status was assigned (control; treatment). Finally, the gender of the MP delivering the speech was assigned (man; woman).

Each respondent completed the task three times. For a given respondent, styles and policies were sampled without replacement from round-to-round, such that once a respondent had read a speech representative of a style or policy, they did not read a second speech representative of the same style or policy. For example, if a respondent was assigned ‘emotion’ on the first response, they could only be assigned ‘aggression’ or ‘evidence’ on the second and the remaining style on their final response. Similarly, if a respondent was assigned ‘transport’ on the first response, they could only be assigned ‘housing’ or ‘health’ on the second and the remaining policy area on their final response. Style treatment status and gender were sampled with replacement.

Per task, each respondent was asked three questions. First, for all styles, respondents were asked whether they ‘agree or disagree that the MP seems likeable’. Secondly, for all styles, respondents were asked whether they ‘agree or disagree that the MP seems competent’. Thirdly, respondents were asked whether they ‘agree or disagree that the argument made by the MP is [emotional/aggressive/evidence-based]’. Respondents were only asked how emotional, aggressive or evidence-based they found an argument to be for the style assigned. For instance, if assigned emotion, they were asked ‘do you agree or disagree that the argument made by [MP name] is emotional’ but not whether they perceived the argument to be aggressive or evidence-based. An example prompt is shown in Figure 1. Given the three observations per respondent and 1,676 respondents, the total number of observations is 5,028, or 1,676 per style.

Figure 1. Example experiment prompt (evidence, statistics, transport, woman).

Methodology

Outcome and Explanatory Variables

The five outcome variables are each measured on five-point Likert scales that range from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ and include a ‘don't know’ option. Likert scales were selected to maximize respondent interpretation of each of the scale points: first, the likeability evaluation of an MP; secondly, the competence evaluation of an MP; thirdly, the perceived emotion of an argument; fourthly, the perceived aggression of an argument; and, fifthly, the perceived evidence of an argument. I drop all ‘don't know’ responses. There are two main explanatory variables: first, the gender of the MP (0 for a man; 1 for a woman); and, secondly, the style treatment, which describes the treatment group status of the style and takes the value of 0 for the control conditions (non-emotional style, non-aggressive style and statistical evidence) and 1 for the treatment conditions (emotional style, aggressive style and anecdotal evidence).

Empirical Strategy

Responses from the emotion, aggression and evidence styles are modelled separately, as the expected direction of the gender effect differs depending on the style. For each, I estimate a series of ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models to investigate my key quantities of interest. First, to assess whether style usage affects voters' evaluations of politicians and perceptions of their arguments, I estimate a series of models for the five outcomes ![]() $Y_{i_( _j_)} $ for an individual i in a style j of the following form:

$Y_{i_( _j_)} $ for an individual i in a style j of the following form:

where α in each model describes the average emotion, aggression, evidence, likeability or competence in the control conditions (non-emotional style, non-aggressive style and statistical evidence), and α + β 1 describes the same quantities in the treatment conditions (emotional style, aggressive style and anecdotal evidence).

Secondly, to assess whether the effects of style usage on voters' evaluations of likeability differ by MP gender, for each style, I estimate the following:

$$\eqalign{& Likeability_{i_( _j_)} = \alpha + \beta _1WomanMP_j + \beta _2TreatmentStyle_j + \cr & \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\beta _3( WomanMP_j\cdot TreatmentStyle_j) + \gamma X_{i_{__(} _j_{__)}} + \varepsilon _i} $$

$$\eqalign{& Likeability_{i_( _j_)} = \alpha + \beta _1WomanMP_j + \beta _2TreatmentStyle_j + \cr & \;\;\;\;\;\;\;\beta _3( WomanMP_j\cdot TreatmentStyle_j) + \gamma X_{i_{__(} _j_{__)}} + \varepsilon _i} $$where β 1 in each model describes the difference between men and women when using the control styles (non-emotional, non-aggressive and statistical evidence), β 2 describes the difference between using control and treatment styles (emotional style, aggressive style and anecdotal evidence) among men, and β 3 is the key quantity of interest, which describes the difference in the effect of using treatment styles compared to control styles for women compared to men. I expect the β 3 coefficients in the emotion and evidence models to be positive, as emotion and anecdotes are female stereotype-congruent styles. In aggression, I expect it to be negative, as aggression is incongruent with feminine stereotypes and women should therefore suffer in likeability evaluations compared to men. Lastly, X i is a vector of additional respondent covariates (gender, age and education).Footnote 3

Thirdly, to assess whether the effects of style usage on voters' evaluations of competence differ by MP gender, for each style, I estimate the following:

$$\eqalign{& Competence_{i_( _j_)} = \alpha + \beta _1WomanMP_j + \beta _2TreatmentStyle_j \;+ \cr & \;\;\;\;\;\beta _3( WomanMP_j\cdot TreatmentStyle_j) + \gamma X_{i_{__(} _j_{__)}} + \varepsilon _i} $$

$$\eqalign{& Competence_{i_( _j_)} = \alpha + \beta _1WomanMP_j + \beta _2TreatmentStyle_j \;+ \cr & \;\;\;\;\;\beta _3( WomanMP_j\cdot TreatmentStyle_j) + \gamma X_{i_{__(} _j_{__)}} + \varepsilon _i} $$where β 1, β 2 and β 3 describe the same quantities as earlier. I expect β 3 in the model for emotion to be positive, suggesting that when women conform to feminine stereotypes, they receive a greater competence reward than men. For aggression, I expect β 3 to be negative, suggesting that women incur negative competence evaluations when they violate feminine stereotypes. For evidence, β 3 will be negative, as I expect that women are rewarded in competency evaluations when they deliver statistical as opposed to anecdotal arguments. Lastly, X i is a vector of additional covariates (gender, age, education and political attention).

Finally, to assess whether politician gender leads to differences in ![]() $PerceivedStyle_{i_{__(} _j_{__)}} $, for each style, I estimate the following:

$PerceivedStyle_{i_{__(} _j_{__)}} $, for each style, I estimate the following:

$$\eqalign{& PerceivedStyle_{i_( _j_)} = \alpha + \beta _1WomanMP_j + \beta _2TreatmentStyle_j \;+ \cr & \;\;\;\;\;\;\beta _3( WomanMP_j\cdot TreatmentStyle_j) + \gamma X_{i_{__(} _j_{__)}} + \varepsilon _i} $$

$$\eqalign{& PerceivedStyle_{i_( _j_)} = \alpha + \beta _1WomanMP_j + \beta _2TreatmentStyle_j \;+ \cr & \;\;\;\;\;\;\beta _3( WomanMP_j\cdot TreatmentStyle_j) + \gamma X_{i_{__(} _j_{__)}} + \varepsilon _i} $$where β 1, β 2 and β 3 describe the same quantities as earlier, and X i is a vector of additional covariates (gender, left–right placement, age and education).

In the empirical strategy described earlier, I outline numerous statistical tests, and there is risk of the multiple comparisons problem. To assess whether the results are robust, I carry out subsequent analyses with adjusted p-values that control for the false discovery rate using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure (Benjamini and Hochberg Reference Benjamini and Hochberg1995). The results reported here are unadjusted, and the adjusted p-values are reported in the Online Appendix.

Results

Unconditional Effects

In Figure 2, I present the results from the models described earlier in Equation 1. There are several findings to note. First, the top panel – which shows the estimated difference between treatment and control styles for the style perception outcomes – highlights that the treatments were successful in shifting perceptions. The aggressive and emotional styles were perceived as significantly more aggressive and emotional than the non-aggressive and non-emotional styles. Further, statistical evidence was perceived as significantly more evidence-based than anecdotal evidence. Voters therefore do perceive the treatments as more representative of the styles than the controls.

Figure 2. Unconditional relationship between control and treatment style usage, style perceptions, and MP likeability and competence evaluations.

Secondly, the styles that politicians use influences voters' evaluations of their likeability: aggressive politicians are significantly less likeable than non-aggressive politicians, and politicians using anecdotes are significantly more likeable than politicians using statistical evidence. While the point estimate suggests that emotional politicians are more likeable than non-emotional politicians, the effect is non-significant.

Thirdly, in the bottom row, I document how style usage influences voters' competence evaluations. Politicians using non-aggressive and non-emotional language are evaluated as more competent than those using aggressive or emotional language. Further, politicians are evaluated as more competent if they use statistical evidence as opposed to anecdotal evidence. Therefore, the styles that politicians use influence how voters evaluate them. However, it seems that certain styles lead to trade-offs in evaluations: for instance, the use of statistical evidence leads to politicians being perceived as less likeable but more competent.

Conditional Effects by MP Gender

Does style usage matter more for women than men? Figure 3 shows the results for the likeability outcomes in the top row. I expected that women would be evaluated as more likeable when they express styles that are congruent with feminine stereotypes and, conversely, suffer in likeability evaluations when they violate stereotypes. The top-left panel shows the results for aggression. Here, both men and women politicians are punished for being aggressive. The effect is larger for women than for men, but this difference is non-significant. The top-middle panel shows the results for emotion. Here, while the direction of the effect suggests that emotional arguments improve likeability among women but not men, the effect is again non-significant. Further, as expected, men are not penalized when they use stereotype-incongruent styles (non-emotional). The top-right panel shows the results for evidence. I again do not see that women are penalized when they express styles that are incongruent with female stereotypes (statistics) compared to styles that are congruent with female stereotypes (anecdotes).

Figure 3. Conditional relationship between MP gender, style treatment group, style perceptions and MP likeability and competence evaluations.

Note: The emotional style, non-aggressive style and anecdotal evidence are female stereotype-congruent, and the non-emotional style, aggressive style and statistical evidence are female stereotype-incongruent.

Consequently, there is no evidence that women politicians are disproportionately penalized in likeability assessments for using styles that are stereotype-incongruent. As Figure 2 shows, there is, however, good evidence that the styles politicians use does affect voters' likeability assessments. When politicians use styles consistent with ‘communal’ stereotypes, they are perceived as more likeable than when using styles consistent with ‘agentic’ stereotypes.Footnote 4 That voters find politicians to be more likeable when they express styles consistent with the concept of communality may not be a surprising finding given that communal stereotypes are associated with being warm, kind, emotional and people-oriented (Schneider and Bos Reference Schneider and Bos2019).

The middle-row plots in Figure 3 show the results for the competence outcomes. In the middle-left panel, I show the results for aggression. There is no evidence that either men or women are perceived as more competent when they are aggressive than when they are not. For emotion, there is no evidence that women are evaluated as more competent when they express styles that are congruent with female stereotypes (emotional style). However, the use of female stereotype-congruent styles results in men being evaluated as less competent than female stereotype-incongruent styles. For evidence, I again see that neither men nor women are evaluated as more competent when they use either anecdotal or statistical evidence.

Therefore, I find no evidence that women in particular are penalized in competence evaluations when they express female stereotype-incongruent styles. As with likeability, voters' competency evaluations of politicians are affected by the styles they use. When politicians express styles consistent with ‘communal’ stereotypes, they are perceived as less competent than when expressing styles consistent with ‘agentic’ stereotypes.Footnote 5 That voters find politicians to be more competent when they express styles consistent with agentic stereotypes again seems to be intuitive finding given the compatibility between agentic stereotypes and leadership stereotypes (Bauer Reference Bauer2017). The findings for emotion and aggression are consistent with work by Brooks (Reference Brooks2011), who finds no double standard in the extent to which voters penalize men and women politicians for their expressions of anger and tears.Footnote 6

The bottom row in Figure 3 shows the results for the style-perception models. In the left panel, voters do perceive politicians as more aggressive when they deliver aggressive arguments than when delivering non-aggressive arguments; however, there is no evidence that this is gendered. The middle plot shows a very similar result: voters do perceive emotional arguments to be more emotional than non-emotional arguments, but this is again not gendered. Finally, the bottom-right plot shows that while voters perceive statistical arguments as more evidence-based than anecdotal arguments, there is again no evidence that this effect is gendered. Voters do not perceive anecdotal or statistical arguments delivered by men to be more evidence-based than equivalent arguments delivered by women. Further, I also expected that differential perceptions of styles might serve as a mechanism through which voters differentially evaluate politicians. I find no evidence of differential effects for style perceptions; consequently, variation in likeability and competence evaluations are very unlikely to be explained by differential perceptions of styles themselves.

In the theory outlined earlier, I argued that women would be punished when they communicate in ways that are incongruent with traditional ‘communal’ female stereotypes. However, while I find that the styles politicians use have important consequences for voters' evaluations, I find no evidence that women disproportionately suffer, at least with respect to likeability and competence evaluations, when they express styles that are incongruent with female stereotypes. Further, I find no evidence that voters' perceptions of the styles themselves are gendered.Footnote 7

Conditional Effects by Voter and MP Gender

How might (gendered) judgements of the styles politicians use vary by voter gender? Prior work examining the importance of voter gender on evaluations of politicians has produced inconclusive results. Some work has uncovered no differences between men and women voters (Bauer Reference Bauer2015b), while other work finds that voters may be less likely to penalize politicians from their own gender (Rudman and Goodwin Reference Rudman and Goodwin2004). To assess heterogeneous effects by voter gender, I carry out two sets of analysis. First, I examine whether men and women voters are equivalently sensitive to politicians' style usage. In the Online Appendix, I assess this by interacting voter gender and style treatment group status for each of the outcomes. Only for the evidence style type are there differences between men and women voters. While men do not find politicians to be less competent or their arguments to be less evidence-based when using anecdotes than when using statistical evidence, women voters do. Further, while the use of anecdotes improves men voters' likeability assessments relative to the use of statistical evidence, this is not the case for women voters. To the extent that there are differences in how men and women voters evaluate politicians' use of styles, the differences are concentrated among the evidence style.

Secondly, I assess whether men and women voters are differentially sensitive to the extent to which women politicians conform to stereotype-congruent behaviours. In the Online Appendix, I subset the data into men and women voters, and then replicate the main analysis described earlier. While for aggression and evidence, there are no differences, this is not the case for emotion. For likeability, women politicians are rewarded among women voters for expressing emotional styles, instead of non-emotional styles, which is an effect I do not find for men voters. For competence, I find that while women voters find emotional politicians overall to be less competent than non-emotional politicians, they give women more of a competency reward than men for expressing emotional styles. I again see no such effect among men voters. Finally, for perceived styles, I see that women politicians are perceived as particularly emotional compared to men politicians when they express emotional styles, which is an effect I do not see for men respondents.

Therefore, women voters give a larger likeability and competence reward to women politicians who are emotional, and perceive women politicians as more emotional than men politicians. I find no evidence of these effects for men voters. Consequently, to the extent that there is any evidence of women politicians being rewarded for conforming to stereotype-congruent styles, the effects are concentrated among women voters and emotion.

Conclusion

Do the styles politicians use influence how voters evaluate them, and does this matter more for women than for men? In this article, I address these questions through a novel survey experiment, where I present UK voters with speeches in which the argument style and gender of the politician delivering the argument are varied. This enables me to identify, first, whether politicians experience a backlash effect with respect to evaluations of likeability and competence when they deploy styles that are gender stereotype-incongruent, and, second, whether voters' differential perceptions of the styles themselves might explain this backlash.

I report four main findings. First, style usage has important consequences for voters' evaluations of politicians. Politicians who are unaggressive and draw on anecdotes are more likeable, whereas politicians who are unemotional and reference statistics are more competent. Secondly, I find no evidence that voter evaluations of politicians are gendered. Women politicians are not punished for stereotype-incongruent behaviour. Thirdly, while there is clear evidence that voters can identify the styles politicians use, I also find no evidence that voters' perceptions of the styles themselves are gendered. Gender bias in voters' perceptions of the styles themselves is very unlikely to explain variation in the likeability and competence evaluations. Fourthly, I find some evidence that these perceptions and evaluations differ by voter gender.

Across the various styles and outcomes, the main finding I document is therefore that styles influence voters' evaluations of politicians but these evaluations do not vary by MP gender. Why do I find little evidence of gender bias in voters' evaluations, and what implications may these findings have for voting behaviour? First, while I find that style usage influences voters' evaluations of the likeability and competence of politicians, these findings do not, however, enable me to assess whether these evaluations have downstream consequences for voting behaviour. The styles and personalities of leaders have long been considered an important determinant of voters' attitudes (Declercq, Hurley and Luttbeg Reference Declercq, Hurley and Luttbeg1972). Further, as partisanship in the electorate has declined over time (Dalton and Wattenberg Reference Dalton and Wattenberg2000) and voters have become increasingly volatile (Fieldhouse et al. Reference Fieldhouse2019), the styles politicians express and associated evaluations may have even increased in importance as determinants of vote choice, as voters base their decisions on factors beyond party. Further, while I cannot directly assess whether these evaluations influence vote decisions, previous UK-based work has shown that voters' evaluations of politicians' competency do influence their voting preferences (Green and Jennings Reference Green and Jennings2017). It is therefore not unreasonable to assume that likeability and competence evaluations may inform vote intention.

My findings suggest that politicians may face trade-offs in evaluations: while styles compatible with communality lead to positive likeability evaluations, styles compatible with agency lead to positive competency evaluations. Should politicians priorities competence or likeability evaluations? Traditional accounts of leadership have suggested that competence is important in informing vote choice (Green and Jennings Reference Green and Jennings2017) and congruent with the traits and behaviours deemed necessary and suitable for leaders (Elgie Reference Elgie2015). As such, according to traditional accounts, we may consider competence the more important evaluation to optimize. However, a trend that is common across many political contexts in recent decades is that voters are increasingly dissatisfied with politics and find that politicians are out of touch and unlike ‘normal people’ (Clarke et al. Reference Clarke2018). In response to voter dissatisfaction with this type of politics and politician, there is an increasing desire for politicians who are instead human, personable, charismatic, engaging and in touch (Valgarðsson et al. Reference Valgarðsson2021). The move to telegenic, human and personable styles has been said to be a core element of the success strategies of populist candidates (De Vries and Holbolt Reference De Vries and Holbolt2020), and recent examples of the use of these styles, such as the widespread fame and popularity of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, suggests that voters and the media find this to be compelling (see, for example, Forbes 2022). As such, while traditional accounts may suggest that ensuring competency is more important in determining candidate success, voters have begun to place increasing importance on the likeability of politicians.

As far as I am aware, we currently lack systematic evidence on which evaluations of politicians among the many that prior work has studied, such as likeability, competence, honesty, hardworkingness or charisma, matter most in informing voting behaviour. A fruitful avenue for future work would, therefore, be to identify which traits voters priorities in their decisions at the ballot box. Such a study would be useful not only for understanding the wider implications of the results I present here, but also for the plethora of experimental studies that assess how a variety of features of politicians' behaviour – such as whether they are corrupt (Eggers, Vivyan and Wagner Reference Eggers, Vivyan and Wagner2017) or loyal to their party (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell2019) – influence how voters evaluate them.

Finally, at the core of the idea that women politicians face double standards when they violate stereotypically expected behaviours is that voters actually hold these expectations for women's behaviour in the first place. However, studies show that the public's perception of the validity of these stereotypes has shifted over time, as women have been seen as increasingly agentic (Eagly et al. Reference Eagly2020). Voters in the UK have also become more gender-egalitarian in their attitudes (Taylor and Scott Reference Taylor and Scott2018) and markedly less likely to support traditional gendered divisions in social roles (Shorrocks Reference Shorrocks2018). Further, there is evidence that UK politicians have come to behave in a way that is less consistent with traditional gender stereotypes. Women politicians have decreasingly used ‘communal’ and increasingly used ‘agentic’ styles over time (Hargrave and Blumenau Reference Hargrave and Blumenau2022). The pessimistic assumption is that this behaviour change might be met by backlash from voters. However, the results presented here suggest that this may not materialize, as UK voters do not seem to unjustly penalize women for stereotype-incongruent behaviour.

Of course, without a study from twenty years ago to compare these findings to, it is not possible to know whether UK voters in previous eras did apply these descriptive stereotypes or punish women politicians for stereotype-incongruent behaviour. Yet, if voters no longer hold the same stereotypical expectations about men's and women's behaviour, and politicians decreasingly behave in accordance with traditional stereotypes, it may not be surprising to uncover that women are not punished for behaviour that violates traditional stereotypes.

Supplementary Material

Online appendices are available: at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123422000515

Data Availability Statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LZ4NKW

Acknowledgements

I am incredibly grateful to Lucy Barnes, Jack Blumenau, Ana Catalano Weeks, Jennifer Hudson, Kasim Khorasanee, Markus Kollberg, Hannah McHugh, Rebecca McKee, Alice Moore, Tom O'Grady, Meg Russell, Jess Smith, Sigrid Weber and Chris Wratil for helpful conversations and insightful comments on, in some cases, numerous drafts of the design, pre-analysis plan and article. I also thank participants at the University of Bath Politics, Languages & International Studies Department Research Seminar, European Political Studies Association 2022 and various working-group seminars at University College London for their thoughtful feedback on this work.

Financial Support

None.

Competing Interests

None.