The relationship between colonization and academia is a vast topic going back many centuries, but the more particular issue of decolonizing the university was brought into sharp focus in 2015 by protests against statues of Cecil Rhodes at the University of Cape Town and then at Oxford the following year. South African scholar Grant Parker commented on the apparent anomaly of how the “offending Rhodes statue at UCT famously received little notice for … many years” (257), with these demonstrations taking place “nearly a generation after the establishment of democracy in the country” (256), long after the statue of Hendrick Verwoerd, architect of apartheid, had been removed from the South African parliament in 1994. But the more recent literal as well as metaphorical deconstructions of statues in many countries were spectacular visual events given heightened public impact by social media networks that did not exist twenty years earlier, and in South Africa this movement also became conflated with issues of student access through a “Fees Must Fall” movement. Within “the Oxford context,” according to organizers of “Rhodes Must Fall,” their “three principal tenets for decolonisation” were “decolonising the iconography, curriculum and racial representation at the university” (Reference Nkopo and ChantilukeNkopo and Chantiluke 137), with the movement being “intersectional” in identifying places where racial injustice overlapped with, and was exacerbated by, similar forms of inequity in class or gender.

Decolonization itself was defined by historian John Springhall as “the surrender of external political sovereignty, largely Western European, over colonized non-European peoples, plus the emergence of independent territories where once the West had ruled, or the transfer of power from empire to nation-state” (2). Geoffrey Barraclough, formerly Chichele Professor of Modern History at Oxford, observed that between 1945 and 1960 forty countries with a total population of 800 million, a quarter of the entire world’s population, achieved political independence by rejecting colonial authority, and as far back as 1964 he argued that too many twentieth-century historians had focused their attention on European wars, even though when this history “comes to be written in a longer perspective, there is little doubt that no single theme will prove to be of greater importance than the revolt against the west” (154). It is hardly surprising that such a massive historical shift has carried reverberations in the academic world, nor that much influential decolonial theory and activism have been generated from outside more traditional universities in Europe and North America, often from the Reference SouthernSouthern Hemisphere.

Walter D. Mignolo, for example, though now based at Duke University, is a native of Argentina who has collaborated extensively with Peruvian sociologist Anibal Quijano and Colombian anthropologist Arturo Reference EscobarEscobar to develop models of collective well-being that represent an emphatic break with assumptions of liberal society and a shift to embedding Indigenous and environmental perspectives within political systems. Mignolo’s strategy of “de-linking” is directed “to de-naturalize concepts and conceptual fields that totalize A reality” (Reference Mignolo“Delinking” 459), thus dissolving purportedly universal systems into more “pluri-versal” variants (Reference Mignolo“Delinking” 499). In Latin America this outlook was interwoven in complex ways with liberation theology and given legal expression in 2008 through the valorization of nature as a subject with rights within the constitution of Ecuador (Reference EscobarEscobar 396), and then by the ratification of Bolivia in 2009 under the leadership of Evo Morales as a “Plurinational State,” one explicitly recognizing Indigenous communities (Reference CheyfitzCheyfitz 143). Working from Oceania, Epeli Hau‘ofa emphasized oral fiction, local knowledge, and an experiential proximity that effectively deconstructed what Mignolo called the epistemic “hubris” associated with a mythical “zeropoint” of colonial knowledge (Reference Smith and Tuck“Introduction” 5), thereby underlining how every angle of vision necessarily derives from somewhere specific. In Africa, struggles over apartheid and Rhodes were foreshadowed by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s 1972 essay “On the Abolition of the English Department,” which discussed a proposal at the University of Nairobi to replace English with a Department of African Literature and Languages, and by his 1986 book Decolonizing the Mind, which analyzed more comprehensively the intellectual relation between African and European languages.

It is important to recognize the subtlety of Ngũgĩ’s argument in the latter work. He does not suggest English or European culture is simply redundant, but that there should be a realignment of epistemological assumptions in line with geographical reorientations. “What was interesting,” noted Ngũgĩ, “was that … all sides were agreed on the need to include African, European and other literatures. But what would be the centre? And what would be the periphery, so to speak? How would the centre relate to the periphery?” (Reference Thiong’o89–90). As with Edward Said, whose critical work similarly invokes heterodox geographies to interrogate Western culture’s hegemonic assumptions, Ngũgĩ’s thinking was significantly shaped by Joseph Conrad, whom Simon Gikandi described as having a “substantive” influence on the Kenyan scholar’s work (Reference Gikandi106).1 Though one of the enduring benefits of decolonizing the university world has been to integrate Africa, Latin America, and Oceania more fully into discursive intellectual frameworks, this has involved more a repositioning than a discarding of Western cultural traditions. Nevertheless, there are important shifts of emphasis associated with this decolonial impetus. Mignolo defined it “as a particular kind of critical theory and the de-colonial option as a specific orientation of doing” (Reference Smith and Tuck“Introduction” 1), and these differentiate it in his eyes from the postcolonial theory that became very popular in English departments from the 1990s onward, which tended to leave familiar hierarchies in place. In a harsh critique of Homi Bhabha’s work, Priyamvada Gopal suggested the readings of “psychic ambivalence” (15) Bhabha attributes to postcolonial texts modulate too comfortably into the kinds of equivocation associated with “Whig imperial history’s own rendering of imperialism as a self-correcting system that arrives at emancipation or decolonization without regard to the resistance of its subjects” (Reference Gopal19). For Gopal, the forms of structural hybridity foregrounded in the work of Bhabha or Gayatri Spivak were readily absorbed into a liberal system of academia where it became easy to carry on business as usual.

As with Ngũgĩ’s analysis of how African literature relates to European, these are complicated (and interesting) debates, and it would seem more useful for any English department to provide the space for such ideas to be interrogated, rather than trying to impose any curriculum predicated upon the impossibility of trying to settle all such questions in advance. One of the historical advantages of Cambridge University, where Gopal is now based, is its relatively decentered structure, organized around some thirty colleges, which makes it difficult for centralized administrative authority of any kind to enjoy unobstructed sway. Salman Rushdie complained in 1983 about Cambridge’s institutional use of “Commonwealth Literature,” which he described as a “strange term” that “places Eng. Lit. at the centre and the rest of the world at the periphery,” a notion he described as “unhelpful and even a little distasteful” Reference Rushdie(“Commonwealth” 61). However, that did not prevent him from pursuing his interest in Islamic culture during his History degree at Cambridge, with Rushdie recalling it was while studying for a special paper on the rise of Islam that he “came across the story of the so-called ‘satanic verses’ or temptation of the Prophet Muhammad” (Reference Rushdie“From an Address” 249), a story he subsequently embellished in his controversial novel The Satanic Verses (1988).

Following a similarly contrapuntal pattern, Caryl Phillips, who was born on the Caribbean island of Saint Lucia and grew up in Leeds before reading English at Oxford in the late 1970s, chose in his final year an optional paper on American Literature, since this gave him the opportunity to study for the first time Black writers: Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, James Baldwin. Though Britain at this time “was being torn apart by ‘race riots,’” Phillips later recalled, “there was no discourse about race in British society and certainly no black writers” on the mainstream Oxford English curriculum (Reference 40Phillips“Marvin Gaye” 35). Under the aegis of Warton Professor John Bayley and his wife Iris Murdoch, the Oxford English Faculty at that time promoted a soft Anglican ideology based around the belief that idiosyncratic “human” qualities necessarily trumped any theory of social circulation. There are, of course, respectable intellectual rationales for this approach, involving a privileging of biography and what Murdoch, a former Oxford philosophy tutor turned novelist, called in her polemical rejection of existential abstraction a stance “against dryness.” But this meant that undergraduates studying American literature tended to be uncomfortable discussing questions of race, with a special paper on William Faulkner when I taught there in the first decade of the twenty-first century attracting essays that made him appear to resemble Virginia Woolf, as the students focused more confidently on stylistic streams of consciousness than on representations of racial tension in Faulkner’s fiction. The same thing was true at Cambridge, where I worked between 1999 and 2002 after the early death of Tony Tanner. Tanner’s inventive and courageous work had helped to establish American Literature as a viable option on the highly traditional Cambridge English syllabus, but his own emphasis on the legacy of transcendentalism, and his critical understanding of American writing as an exploration of new worlds of “wonder,” had led to a synchronic understanding of the field as synonymous with a mythic quest for freedom. Many students in the third-year American Literature seminar did not know or care about the dates of the US Civil War, nor did they see distinctions between antebellum and postbellum periods as relevant to their textual close readings.

None of these pedagogical issues was insuperable, and part of the pleasure in university teaching involves encouraging students to reconsider familiar authors from a more informed perspective. Moreover, the polycentricity of both Oxford and Cambridge helped ensure these intellectual agendas were driven largely by productive academic debates and disagreements, rather than, as at some other places I have worked, by deans or vice chancellors who fancy themselves as charismatic leaders and wish to impose “a future vision” of their own on the university. Phillips’s own novels involve, in his words, “a radical rethinking of what constitutes British history” (Reference BraggBragg), while avoiding “the restrictive noose of race” (Reference Smith and Tuck“Introduction” 131), which as a category Phillips takes to be inherently reductive, and in this sense his fiction might be said to have internalized in paradoxical ways aspects of the Oxford idiom, even in resisting its ideological narrowness.

Mark Twain, who in Following the Equator (1897) directly addressed Cecil Rhodes’s legacy in South Africa, also retained a guarded attitude toward questions of race and colonization, one that combined a sense of outrage at Rhodes’s depredations with a darker fatalism shaped by Twain’s sense of Social Darwinism as an inevitable force. Twain’s presentation of Rhodes is consequently bifurcated, in line with the structural twinning that runs through much of his writing: “I know quite well that whether Mr. Rhodes is the lofty and worshipful patriot and statesman that multitudes believe him to be, or Satan come again, as the rest of the world account him, he is still the most imposing figure in the British empire outside of England” (Reference Twain708). Even critics who highlight Twain’s radical aspects acknowledge these contradictions: “I confess,” remarked John Carlos Rowe of Following the Equator, “that my representation of Twain’s anti-imperialist critique of the British in India does not account for Twain’s vigorous defense of the military conduct of the British in suppressing the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857” (Reference Rowe132). Such ambivalence does not, of course, invalidate Twain’s engagement with colonial cultures but makes it more thought-provoking. It does no favor to either literary studies or decolonial praxis to circumscribe such writers within restrictive interpre-tative grooves, and Kerry Driscoll’s work on Twain and “Indigenous Peoples” perhaps misjudges the tone of Following the Equator in its claim Twain here “rages against the unjust dispossession of Australian Aboriginals and the genocidal efforts of colonial settlers who left arsenic-laced flour in the bush for them to eat” (Reference Driscoll11). It is true that foregrounding Twain’s darker facets can generate more pointed discussions than were customary during the heyday of Huckleberry Finn’s “hypercanonization,” when the novel was celebrated unproblematically as a fictional epitome of the free American spirit, and Driscoll illuminatingly expands scholarship on Twain and race to encompass questions of dispossession and Indigeneity as well as “African Americans and slavery” (4), with the latter having now become more familiar in critical discussions of the author.2 There has of course been much valuable work since the 1970s to recover American writers who had been excluded from traditional canonical Reference Hallformations, but one of the most productive aspects of such inclusiveness has been a shift in the analytical relation between Black authors and established White figures such as Twain, Poe, or Henry James, a reorientation outlined most influentially by Toni Morrison in her Harvard lectures published as Playing in the Dark (1992). But Morrison’s treatment of these issues is characteristically oblique, indicating how racist assumptions in these classic texts often circulate in underhand ways, and Twain’s black comedy tends similarly to avoid narrative closure or polemic.3

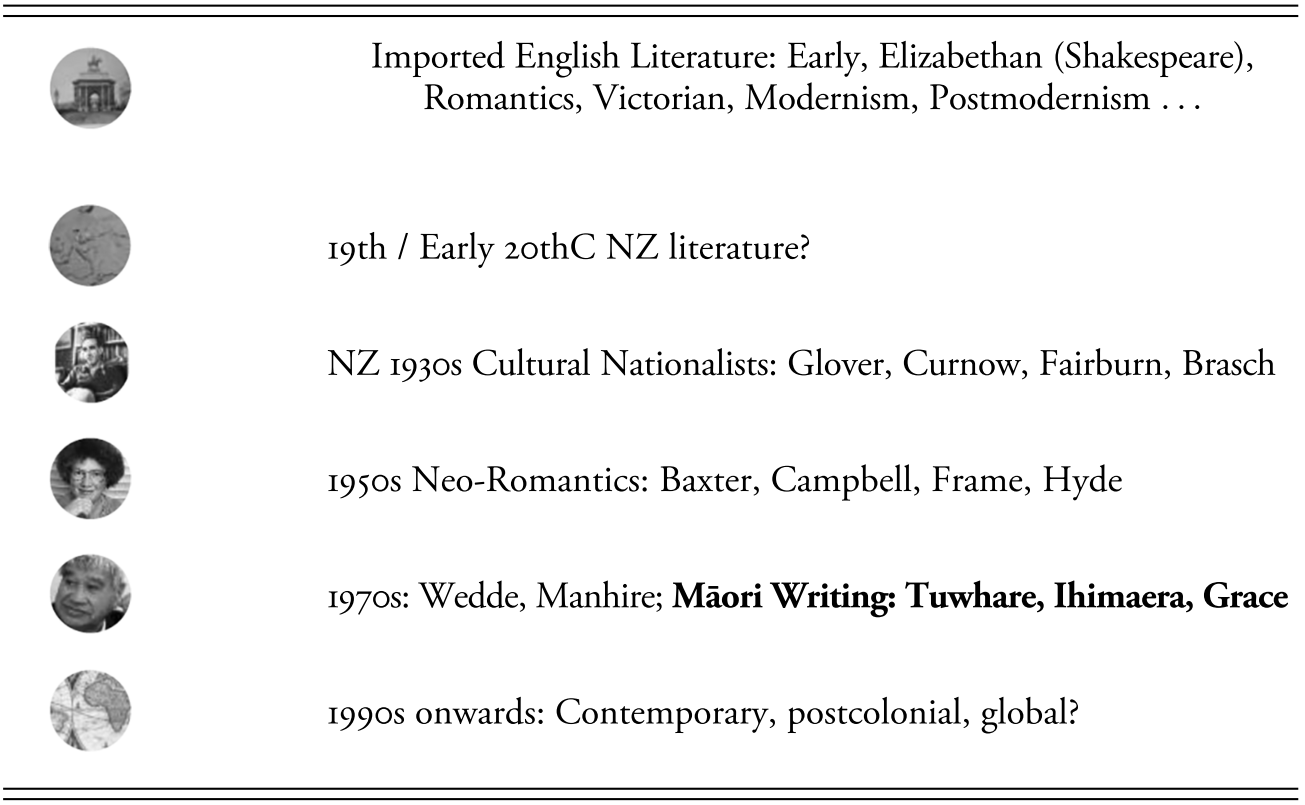

The point here is simply that racial representations in literature are necessarily multifaceted and variegated. One of the qualities distinguishing the humanities from the social sciences, according to Helen Small, is their greater “tolerance for ambiguity” (Reference Small50), with Roland Barthes declaring “nuance” to be synonymous with “literature” itself (Reference Barthes11). Nevertheless, one clear benefit of decolonization for literary studies has been to demystify myths about the “universality” of American or European value systems and to interrogate subject positions whose implicit hierarchies have remained unacknowledged. James D. Le Sueur remarked on how one enduring legacy of the French–Algerian War (1954–62) was the way it generated a “fundamental reconsideration” (167) of French culture’s place in the world, just as Dipesh Chakrabarty has argued for “provincializing Europe” more generally. In her account of the development of English departments in Australian universities, Leigh Dale described how old-style professors in the earlier part of the twentieth century tended to promote Anglophile ideas, with Donald Horne recalling how E. R. Holme, McCaughey Chair of Early English Literature at the University of Sydney until 1941, would use Sweet’s Anglo-Saxon Primer “as a text for a series of sermons on the virtues of Empire” (67), with any interest in Australian literature being counted until the 1970s as, in Dale’s words, “equivalent to an intellectual disability” (Reference Dale143). But the advent of postcolonial theory in the last decades of the twentieth century comprehensively changed these power dynamics, and conceptual intersections between different parts of the world are now an established feature of literature courses everywhere. Oxford at the beginning of the twenty-first century changed the title of its various undergraduate period papers from “English Literature” to “Literature in English,” an apparently minor emendation that seemed to pass unnoticed by many college tutors, but one that resolved the previous ambiguity about whether the adjective “English” referred to language or nation and so allowed the possibility of studying, say, Les Murray or Adrienne Rich alongside Ted Hughes. Cambridge has retained the traditional nomenclature of “English Literature” but specifies in its outline that “the course embraces all literature written in the English language, which means that you can study American and post-colonial literatures alongside British literatures throughout.” This did not necessarily mean that Oxbridge tutors who had spent half their lives teaching Dickens and George Eliot jumped at the opportunity to teach Indian or Australian literature instead, but it did allow for the possibility for the curriculum to evolve as new academic interests and priorities emerge. Decolonizing any university in substantive terms is always a long-term process rather than one accomplished by apocalyptic cleansing.

Recognition of the wide variety of colonial contexts also allows greater flexibility in understanding how a program of decolonization might be addressed. Australian anthropologist Nicholas Thomas, who now works at Cambridge, emphasizes the manifold dissimilarities of colonial situations, rejecting a “unitary and essentialist” version of “colonial discourse” (3) as “global ideology” (60) in favor of its “historicization” (19), where particular situations in, say, the Solomon Islands or Māori New Zealand are scrutinized for their “conflicted character” (3). This also leads Thomas to be skeptical about the claims of Australian Indigenous culture to any “primordial” purity (Reference Thomas28), an idea he suggests has too often been appropriated for strategic or sentimental purposes. Concomitantly, the notion that decolonial politics should turn exclusively on a restitution of stolen lands might be said misleadingly to conflate pragmatism with philosophy. In complaining that “decolonization is not a metaphor,” American Indigenous scholars Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Tang argued that “when metaphor invades decolonization, it kills the very possibility of decolonization; it recenters Whiteness, it resettles theory, it extends innocence to the settler, it entertains a settler future” (Reference Tuck and Wayne Yang3). Such an emphasis does carry significant purchase in the Indian domain of land restitution that Tuck and Wang prioritize, but it is important to recognize that while land might constitute a form of “knowledge” (Reference Tuck and Wayne Yang14) for some peoples, it certainly did not for those enslaved on American plantations, where they were not able to own land either legally or economically, nor for Jewish people who were banned from holding land in medieval Europe. To inflate a “spiritual” relation to land into an “ontology,” as does Indigenous Australian academic and activist Aileen Moreton-Robinson (Reference Moreton-Robinson15), thus risks aggrandizing the legitimate praxis of specific claims grounded on the issue of territorial “sovereignty” (Reference Moreton-Robinson125) into an unsustainable universalist design.

Such political tensions have been particularly prevalent within Australian academia, where attempts to introduce Indigenous perspectives have often led to controversies around the definition of the subject and the question of who is empowered to articulate the field. At the University of Sydney, for example, an “Aborginal Education Centre” was established in 1989 and renamed in 1992 as the “Koori Centre,” providing a focus for teaching and research led by Indigenous scholars as well as support for students; but this Centre was dissolved in 2012 in an attempt to embed Indigenous knowledge more fully within regular university curricula, with individual academics being redistributed across different departments. The problem here arises not so much from these organizational structures, for which advantages and disadvantages might be adduced on both sides: a separate Koori Centre always risked being intellectually isolationist, but attempts to integrate Indigenous knowledge across the curriculum risk such specificity becoming vitiated, particularly in an era of financial stringency and dwindling appointments. But the more fundamental difficulty turns on a potential displacement of complicated intellectual questions to rigid administrative blueprints within which such theoretical issues might find themselves prematurely foreclosed. There have, for instance, been many debates around the work of Alexis Wright, an astonishing novelist from the Waanyi people, but the reception of her fiction has often become locked within institutional tugs of war linked to proprietorial concerns, with some identifying her work specifically with Indigenous politics and language, while others have sought to associate it with global environmentalism and magical realism. Some Indigenous scholars regard the “mainstreaming” of their field as inherently hazardous, on the grounds that any “reconciliation” fundamentally involves “rescuing settler normalcy” and “ensuring a settler future” (Reference Smith, Tuck and YangSmith, Tuck, and Yang 15); others emphasize “the importance of relationality,” with Sandra Styres suggesting that “decolonizing pedagogies and practices open up spaces … where students can question their own positionalities, prior knowledge, biases, and taken-for-granted assumptions” (Reference Styres33). These arguments will inevitably continue, but it is crucial they are allowed a viable academic framework within which to evolve over time, perhaps in ways that are currently difficult to predict.

One indisputable contribution of Australian cultural theory to literary studies over the past decade has been to make debates around settler-colonial paradigms more prominent. The work of Patrick Wolfe, Lorenzo Veracini, and others, which had heretofore been regarded as relevant largely within an Australian or Pacific Island context, is now deployed to elucidate settler Reference Hallformations in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa as well as the United States, with Phillip Round in a 2019 essay on nineteenth-century US literature describing settler colonialism as “the foundational principle of all American sovereignty discourse” (Reference Round, Marrs and Hager62). Tamara S. Wagner similarly wrote in 2015 of how “in the last few years, new interest in settler colonialism has helped us see what postcolonial criticism has traditionally left out” (Reference Wagner224), while Tracey Banivanua Mar observed a year later that although the Pacific had generally been seen as “an afterthought in most overviews of decolonization,” this has changed “productively” in recent times (Reference Mar8). However, such perspectival expansiveness has introduced concurrent anxieties about a loss of traction for Australian Literature as a discrete field, along with concern that what Russell McDougall called “transnational reading practices” might lead to “deteriorating interest in Australian Literature” and its supersession by a generic model of “world literary space” (Reference McDougall10), in which settler colonialism manifests itself as a more amorphous phenomenon. There are no easy answers to these questions, but they are complex equations that literary studies should always be thinking through: relations between hegemony and decolonization, the promise but also potentially illusory capacity of regional autonomy, the perennial liability to cultural appropriation through economic and political incorporation.

*

The third of the “principal tenets” for Rhodes Must Fall, “racial representation at the university” (Reference Nkopo and ChantilukeNkopo and Chantiluke 137), is in many ways more difficult to address than decolonizing its iconography or curriculum, since this necessarily involves confronting the kind of systematic racism that has long been endemic to British as well as most Western societies. The statistics in themselves are shocking: in 2016, 27 percent of pupils who attended state schools in Britain were Black, but there were only a handful of Black undergraduates at Oxford, with Patricia Daley, a contributor to Rhodes Must Fall, being the first Black academic to be appointed as a university lecturer at Oxford as late as 1991. The reasons for such anomalies are complex, involving what can be seen in retrospect as excessive trust during the second half of the twentieth century in the meritocratic model promoted by UK government policies after 1945, where applicants for admission were judged solely on their academic performance according to supposedly objective criteria.4 British universities were slower than those in the United States to calibrate for different social and educational contexts, and apart from the overall inequity of this process it also involved a significant loss of scholarly capacity, as if professional football clubs were to base recruitment only on the number of goals students had scored for their high-school team rather than their overall playing potential.

Equal access to higher education is crucial to the health as well as integrity of any academic system, but often resistance to change was linked to forms of unconscious bias that the Black Lives Matter movement has effectively highlighted. As Chakrabarty noted, while “racism” as a theoretical concept may no longer be viable, subtler forms of racial profiling and discrimination have nevertheless proliferated (Crises Reference Chakrabarty142).5 Sara Ahmed has written about how ubiquitous university offices of “Institutional Diversity” remain blind to what she called “kinship logic: a way of ‘being related’ and ‘staying related,’ a way of keeping certain bodies in place. Institutional whiteness,” Ahmed concluded, “is about the reproduction of likeness” (Reference Ahmed38). Again, this emphasis on “kinship” is by no means a recent or exclusively British phenomenon, nor one arising solely from the idiosyncrasies of the English class system; in 1666 at the University of Basle, for instance, all but one of the professors were related to each other, while in the 1790s at Edinburgh six chairs in the medical faculty changed hands, with five of them going to sons of former professors (Reference VandermeerskVandermeersk 228). Less blatantly, however, Oxbridge often accepted students with whom it felt “comfortable” through the narrowness of its own perspective about what constituted academic value. Since this is an issue embedded historically within the social structures of British life, it is not readily susceptible to amelioration simply through educational reform. In his chapter on university life in English Traits (1856), Ralph Waldo Emerson described Oxford and Cambridge as “finishing schools for the upper classes, and not for the poor,” with England regarding “the flower of its national life” as “a well-educated gentleman” (Reference Emerson and Wilson117). It was this emphasis on individual character and manners as the epitome of cultural value that contributed for so long to social and racial circumscriptions of the student population.

Such pressures toward conformity can also be attributed in part to the notion, common since medieval times, that the academic world should properly be subservient to the jurisdiction of a secular state. Conflicts between the papacy and the Holy Roman Empire were famously replicated in England in 1535, when Henry VIII sent royal visitors to scrutinize the Oxford and Cambridge curricula, with a view to realigning it in accordance with new state priorities by eliminating the teaching of systematic theology and abolishing degrees in canon law (Reference LoganLogan). In this light, more recent political moves to make universities serve what Bill Readings called “the force of market capitalism” (Reference Readings38) have a venerable antecedence. Back in the twelfth century, as R. W. Reference SouthernSouthern observed, the great majority of students went on to become “men of affairs” (Reference Southern199), and for most students, then as now, university was more important as an opportunity for enhanced social and economic status rather than intellectual inquiry. This, of course, is one reason the middle classes have been so desperate to protect university space in order to benefit their own children’s future, with class mobility in academic environments being no less a source of potential friction than racial equity, and Matt Brim describing “top schools” in the United States as “unambiguous drivers of class stratification” (Reference Brim86).

Since national economies started to become increasingly dependent on inReference Hallformation technology in the 1990s, there has been exponential pressure from national bodies for universities to produce graduates adept at gathering and organizing data, with all developed nations rapidly expanding their student populations in the interests of supporting their economies. In 2013 there were some 160 million students enrolled globally (Reference Schreuder and SchreuderSchreuder xxxiv), and this has led to even more pressure for higher education to serve the interests of the state. This in turn has produced a more dirigiste version of academia as comprising “managed professionals” (Reference Slaughter and RhoadesSlaughter and Rhoades 77) employed to execute research agendas often dictated by a university’s upper administration, in line with government funding priorities. Symbiotically intertwined with these systematic pressures toward conformity has been the fear among some observers “in every generation,” as Collini commented, that the university world “was all going to the dogs” (Reference Collini33). John Henry Newman in 1852 declared: “A University, I should lay down, by its very name professes to teach universal knowledge” (Reference Newman and Ker33); but this etymological link between universities and universalism has always been fractious and contested, particularly given the perennially tense relations between academic and political worlds. In the Middle Ages, universitas was a term derived from Roman law that described a union of people bound together by a common occupation, an arrangement that gave it immunity from local systems of justice under the merchant code; but in 1205 Pope Innocent III cannily expanded this corporate meaning to embrace his vision of the universitas as engaged in universal learning, addressing a papal letter to “universis magistris et scholaribus Parisiensis,” to all masters and students in Paris (Reference PedersenPedersen 101, 151). Nevertheless, medieval universities always had to fight to retain some measure of freedom, with their leaders often attempting to play off civic and religious authorities against each other.

In this sense, Immanuel Wallerstein’s view that the model of the medieval university “essentially disappeared with the onset of the modern world-system” (Reference Wallerstein59) seems doubtful, since universities have always been forced to negotiate uneasily with political and economic pressures. Reference SouthernSouthern commented on how the growth of scholasticism in the twelfth century heralded a “striving towards universality,” with lecturers subsuming all “local peculiarities” of time and place within universal systems of knowledge (Reference Southern211), but competing claims of local and global have fluctuated over time and place. Many intellectual developments occurred when scholars working in universities challenged social or academic conventions: Peter Abelard’s dialectical theology, for example, was seen as heretical in the twelfth century, even though two of his students eventually went on to become pope, while in the 1790s Immanuel Kant was reproved by a Prussian superintendent for his dissemination of unorthodox ideas (Reference RueggRuegg 7). There has thus been a long and distinguished tradition in universities of dodging the bullets, of exploiting university infrastructures and resources to evade institutional authorities. Such transgressive practices are common across all disciplines, from Galileo’s work on astronomy at the University of Padua between 1592 and 1610, to John Locke in the seventeenth century revising the basis of empirical philosophy, to Adrienne Rich in the twentieth century recasting formal poetic traditions in feminist, emancipationist styles, a project she undertook while working in a challenging urban environment at the City University of New York. In disagreeing with Eric Ashby’s claim that the scientific revolution in the seventeenth century gained its momentum from outside academia, Roy Porter pointed to how universities “provided the livings” and “posts” (Reference Porter545) for most of the radical figures who advanced principles of physiology, medicine, and mathematical logic during this era: Carl Linnaeus, William Harvey, Isaac Newton.

From a historical perspective, then, Claire Gallien’s assertion that “decolonial studies are not soluble in the neo-liberal university” (Reference Gallien9) would appear dubious. It is not clear why a “neo-liberal” academic framework, for all its obvious reifications and follies, should be more of an impediment to innovative work than the scholastic environment of the Middle Ages, or the gentlemanly codes of conduct that predominated in the universities of eighteenth-century Germany, when professors and students liked to don the clothes of aristocrats and knights to display their social standing (Reference SimoneSimone 316). As Porter remarked, despite all the pressures toward standardization, universities have proved over time to be “immensely durable” sites for the pursuit and dissemination of new knowledge (Reference Porter560). One of the reasons Peter Lombard’s Four Books of Sentences was so popular among students in twelfth-century Paris was because it was a sourcebook of excerpts assembled “so that the enquirer in future will not need to turn over an immense quantity of books, since he will find here offered to him without his labour, briefly collected together, what he needs” (Reference SouthernSouthern 198), and a similarly instrumental view of higher education is readily apparent in academic marketplaces today. Nevertheless, universities still offer scope for productive work, even if indirectly rather than programmatically, since in academia chains of cause and effect, investment and outcome, tend to be linked together more obliquely than administrators and politicians would prefer.

In humanities, Stuart Hall, who played a major role in incorporating racial questions into university curricula during the final decades of the twentieth century, moved as a Rhodes Scholar in 1951 from Jamaica to Oxford, where he stayed until 1957. Hall later found continuities between his understanding of the “always hybrid” nature of “cultural identity” (“Reference HallFormation” 204), linked to a “diasporic way of seeing the world,” and the “diasporic imagination” of Henry James (“Reference HallAt Home” 273), on whom he started but never completed a doctoral thesis at Oxford. “I wanted my PhD to be on American literature,” said Hall, “because it’s somewhat tangential. I’m always circling from the outside. I’m interested in the complexities of the marginal position on the center, which, I suppose, is my experience of Oxford … I thought, I’m a Rhodes Scholar – the whole point of Rhodes was to send these potential troublemakers to the center, to learn.” Given Hall’s recollection of how his pioneering Cultural Studies department at Birmingham in the 1960s was accomplished by “stealth” and “double-dealing,” it is not difficult to see the circuitous influence of this Oxford experience on the development of Cultural Studies in the UK, especially as Hall described the field as initially posing “some key questions about the Americanization of British culture and where English culture was going after the War” (Reference PhillipsPhillips, “Stuart Hall”). While decolonization has been associated more explicitly with Cultural Studies, it has also been linked to the English literary curriculum in roundabout ways. Hall’s contributions, like those of Rushdie and Phillips, indicate how even the most conservative academic frameworks can engender heterodox styles of progressive thought that cannot be reduced simply to the expectations of funders or the often narcissistic visions of founders. Rhodes would never have approved of Hall, but Hall was nevertheless a product of the Rhodes legacy.

The opening up of the world to what Cameroonian scholar Achille Mbembe called “new cognitive assemblages” (Reference Mbembe244) – the pluriverse, the posthuman, the Anthropocene – consequently allows for “new, hybrid thought styles” (243), where traditional horizons can be reconceptualized. Mbembe, who has influenced the work of Judith Butler, described Africa as “a planetary laboratory at a time when history itself is being recast as an integrated history of the Earth system” (252), and the same thing is true of Oceania and Latin America, whose new visibility within the world of global scholarship effectively interrogates more calcified Western models.6 Mignolo wrote of how “decolonial liberation implies epistemic disobedience” (“Reference Mignolo and Walsh.On Decoloniality” 114), implying again crossovers between decolonization and transgression. Similarly, it would be possible to recognize analogies between Hall’s realignment of the epistemological foundation of White British culture by recalibrating it in relation to Black migration and an equivalent displacement of Euroamerican centers of gravity through such a “planetary laboratory.”

Exactly how such global reorientations might manifest themselves will always be open to debate, as the many critical disagreements today about how to define “World Literature” amply demonstrate. Nevertheless, we should not underestimate the long-term social “impact” of the humanities. It is unlikely, for example, that Barack Obama would have been elected president of the United States in 2004 had it not been for the scholarship from the 1970s onward that worked successfully to elucidate blind spots in the American literary canon, sparking revisionist reassessments in the popular fiction of Toni Morrison and many others of how racialist assumptions had become entrenched within society. The recent exponential growth in college student numbers, rising in the United States in 2018 to around 69 percent of high-school graduates, means that university curricula now exert more influence throughout society than during the twentieth century, and the decolonization of the English literary curriculum has played an integral part in this process.

Writing from within Oxford, Patricia Daley argued: “Decolonisation is not about replacing Western epistemologies with non-Western ones, nor is it about prioritising one racialised group over another. It is to create a more open ‘critical cosmopolitan pluriversalism’ – where instead of Eurocentric thought being seen as universal, there is a recognition and acceptance of multiple ways of interpreting and understanding the world” (Reference Daley85). Such “pluriversalism” is categorically different from traditional versions of liberal pluralism, since its focus is not just on authorizing difference per se, but on how geopolitical and environmental variables frame the “pursuit of restitutive justice” that Robbie Shilliam regards as crucial to “the imperial world map” (Reference Shilliam19). While there are different ways of approaching questions of decolonization, they all involve, as Shilliam suggested, a “cultivation of different spatialities and relationalities” (Reference Shilliam22), a decentering of racial hierarchies that runs in parallel to a decentering of geographical hierarchies. To decolonize the university is to restore a sense of its etymological universalism and resist acquiescing in local conventions, whether political, social, or racial; yet this should involve what Wallerstein glossed as a “universal universalism,” rather than a “partial and distorted universalism” (Reference Wallersteinxiv) extrapolated merely from Western centers of power. While such a planetary universalism might be an evasive and infinitely receding concept, it is nevertheless one to which the idea of a university should always aspire.

The university English department in Ireland has a long history, but of that history we have no history. This might appear paradoxical because for much of its existence the English department in Ireland as elsewhere conceived of itself in broadly historicist terms – offering curricula that generally ran from Anglo-Saxon and medieval to modern British literature – and cultivated critical models that can be described as historicist and contextualist in character (Reference NorthNorth). Nevertheless, while the history of education in Ireland is a well-established field, there are no histories of the formation of English departments in Ireland, of the curricula they offered, the agendas they hoped to serve, or of their reconfigurations in the changing world of the university more generally. In this sense, English departments in Ireland can be said to have little substantial historical memory and without such memory attempts to “decolonize” departments run the risk of being uninformed and unsystematic.

That the modern education system in Ireland generally was colonial and imperial in intent and function seems indisputable. In the period after the Tudor, Stuart, and Cromwellian plantations, the English state dismantled the remaining structures of Gaelic society in Ireland and enacted penal laws designed to consolidate the new Protestant Ascendancy, to limit access to land and the higher professions to Catholics, and to anglicize Irish subjects and culture. In 1695, “An act to restrain foreign education” was legislated to limit contact between Irish Catholics and possible continental allies, to which was added a domestic provision forbidding any “person whatsoever of the popish religion to publicly teach school or instruct youth in learning” (Reference McManusMcManus 15). These laws were designed to discourage Catholicism and to encourage Catholics to have their children educated in the available Protestant schools to become loyal subjects of the United Kingdom.

The disenfranchised Catholic population did not readily comply. Instead, Catholic schoolmasters continued to teach surreptitiously in provisional schools often conducted out of doors and in the shelter of hedges, this giving rise to a “hedge school” system that continued until the end of the penal laws in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Historians of these schools conceive of them as “a kind of guerrilla war in education,” in which teachers were obliged constantly to evade law officers and were often prosecuted, especially in times of social unrest. In her account of the hedge schools, Antonia McManus notes, “a school master who contravened penal laws was liable to three months’ imprisonment and a fine of twenty pounds. He could be banished to the Barbados, and if he returned to Ireland, the death penalty awaited him. A ten pound award was offered for his arrest and a reward of ten pounds for information against anyone harbouring him” (Reference McManus17). Despite such strictures, the hedge schools managed to provide education for students intended for the priesthood, for foreign military service, and for those going into business and trading enterprises domestically and overseas. In an increasingly British-dominated world, English was required for social advancement, and the hedge schools provided English instruction. As instruments of both anticolonial resistance and adaption, they probably prefigured in function the more state-sponsored forms of institutional education later developed in the nineteenth century.

Despite the turmoil created by the plantations and the insurrections protesting the new colonial system, the Irish population had grown to 8 million by the 1840s, at a time when that of the rest of the United Kingdom was approximately 18.5 million. By this time, the poorer Irish had become for many in England a byword for papism and poverty, squalor and sedition. Many had also become a ragged and unskilled migratory labor force pouring into England’s and Scotland’s industrial cities. The United Irish Rebellion of 1798, Daniel O’Connell’s mass campaigns for Catholic Emancipation (achieved in 1828) and then for repeal of the Anglo-Irish Union of 1800, and the prominence of several Irish figures in the Chartist movement in England demonstrated that the Irish could be a formidable force for political unrest and rebellion in the United Kingdom as a whole.

Commentators as diverse as Thomas Carlyle and Marx and Engels observed as much. Mixing Biblical-style fulmination with social analysis, Carlyle’s Chartism (1840) deals at length with Irish migration to England and its consequences. Referring mockingly to the Irish migrants as “Sanspotatoes,” an obvious reference to the Parisian “sansculottes,” Carlyle complains that:

Crowds of miserable Irish darken all our towns. The wild Milesian features, looking false ingenuity, restlessness, unreason, misery and mockery, salute you on all highways and by-ways. … He is the sorest evil this country has to strive with. In his rags and laughing savagery, he is there to undertake all work that can be done by mere strength of hand and back; for wages that will purchase him potatoes. … The Saxon man if he cannot work on these terms, finds no work. He too may be ignorant; but he has not sunk from decent manhood to squalid apehood; he cannot continue there. American forests lie untilled across the ocean; the uncivilized Irishman, not by his strength but by the opposite of strength, drives out the Saxon native, takes possession in his room.

Here, colonial clichés and stereotypes agglutinate. They include: the dark simian qualities; the sly civility that combines “misery and mockery” or “laughing savagery”; the degenerate Celtic weakness that is nevertheless stealthy enough to expropriate the more manly Saxon and compel him to emigrate to “untilled” American forests while the slovenly migrant usurps “his room” at home.

Yet though he fulminates, Carlyle does not wholly blame the Irish for their own condition:

And yet these poor Celtiberian Irish brothers, what can they help it? They cannot stay at home and starve. It is just and natural that they come hither as a curse to us. Alas, for them too it is not a luxury. It is not a straight or joyful way of avenging their sore wrongs this; but a most sad circuitous one. Yet a way it is, and an effectual way. The time has come when the Irish population must be improved a little, or else exterminated. Plausible management, adapted to this hollow outcry or that will no longer do: it must be management, grounded on sincerity and fact, to which the truth of things will respond – by an actual beginning of improvement to these wretched brother-men. In a state of perpetual ultra-savage famine, they cannot continue. For that the Saxon British will ever submit to sink along with them to such a state, we assume as impossible.

It is the Kurtz-like reference that what cannot be “improved” must be “exterminated” that catches the eye here. When the Great Famine came later in the same decade, the Irish really did become “Sanspotatoes,” 2 million of them dying of hunger, a further 2 million emigrating. Following that catastrophe, the more militant Irish, at home and in the United States, would also think “extermination” and attribute the British government’s weak and often contemptuous response to Irish starvation and disease as state-sanctioned genocide.

Nevertheless, both in the passage cited here, and in the treatise as a whole, Carlyle’s stress falls on “improvement,” not “extermination.” In place of an ad hoc “plausible management” of what Carlyle represents as a chronic domestic British crisis, what Chartism calls for is the “beginning of an improvement” that will confront what will soon be called “the Irish problem” more systematically. When he is done railing on the inadequacies of English parliamentary reform and bourgeois complacency, what Carlyle finally advocates in Chartism’s closing chapter as the solution to the social unrest unleashed by the industrial revolution comes down to two Es, or really three Es: Education and Emigration, Empire serving as the bridge that connects the first two Es. Education is advocated for the English workers and slatternly Irish, “who speak a partially intelligible dialect of English” (Reference Carlyle28), so both constituencies may be disciplined out of their unruliness and into proper respect for order and authority. Emigration is offered as a response to Malthusian doomsayers; it is a valve that will allow this “swelling, simmering, never-resting Europe of ours” that stands “on the verge of an expansion without parallel” to make verdant the whole earth (Reference Carlyle112).

“Universal Education is the first great thing we mean, general Emigration is the second” (Reference CarlyleCarlyle 98). Education and emigration, in many cases education for emigration, would remain closely imbricated in Irish life throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, but the approaches Carlyle called for in Chartism were in many respects already underway before 1840. The Act of Union passed in 1800 abolished Dublin’s Ascendancy parliament and afterward Westminster directly governed Ireland. The shocks caused by the 1798 Rebellion and O’Connell’s mass campaigns together with rapid transformations brought about by the industrial revolution in England forced a dramatic expansion in British state power and social controls, economic laissez faire notwithstanding. Experiments that were more difficult to implement in the United Kingdom proper were attempted in colonial Ireland, and by the mid-nineteenth century the smaller island possessed a complex of centrally administered social institutions. These included an extensive network of police stations and gaols, workhouses, hospitals, asylums, and, not least, a national education system.

In 1831, the establishment of the Commission of National Education steered Irish education away from Protestant conversion agendas and led to the formation of a state-centralized national education system. Though the Irish clergy of all denominations were mostly initially hostile to a centralized education system, they were nevertheless encouraged to participate as patrons of the new school system. Thus, as Kevin Lougheed comments, “the national school system quickly established itself in Ireland, such that it was one of the dominant suppliers of education in the country by the onset of the Famine in 1845, with close to 3500 national schools educating over 430,000 children” (Reference Lougheed3). By comparison, Lougheed adds, “the state emerged into the English education field much later than in Ireland, only becoming directly involved in education provision from 1870” (Reference Lougheed4). Though the two countries were officially parts of the same state, then, national education took different courses in Ireland and England. In Ireland, the state developed a centralized system earlier and attempted to attach the various clerical denominations to the state by way of school patronage; in England, state involvement was more gradual and there was ultimately less emphasis on religious involvement (Reference LougheedLougheed 5).

Educational innovations in Ireland had consequences that reached well beyond Ireland. In the White settler colonies especially, colonial authorities looked to the imperial center for models as to how to develop their own fledgling educational systems, and Ireland often served as a template. Canada and Australia also had settler populations divided by religion and nationality, and the Irish national school system appeared to offer a model by which to overcome such division and to create self-disciplined subjects loyal to the British Empire. Missions by the various churches to tend to the emigrant communities in the settler colonies brought Irish experience and knowledge to these regions, and this in turn further encouraged a tendency to emulate Irish examples. Akenson, Lougheed, and others note that the basic textbooks introduced for instruction in the Irish national schools remained for thirty years after their introduction what Akenson calls “probably the best schoolbooks produced in the British Isles” (Reference Akenson229). “It can be said that, from the 1840s,” Lougheed observes, “the textbooks published in Ireland became the standard textbooks throughout the British Empire” (Reference Lougheed10).

These textbooks did not contain detailed information on the geography, history, or culture of Ireland and instead presented the United Kingdom as a homogenous society and culture with a superior form of governance from which Ireland particularly and the colonies generally benefitted. As Lougheed remarks:

The importance of the British Empire, with Ireland as a key part, and the “civilising mission” of imperialism were highlighted, especially in the geography sections [of the textbooks]. This emphasised the size and importance of the Empire and also served to inform individuals of opportunities for emigration. … Throughout the publications, racial and cultural views were constructed which privileged European customs. For example, the description of the geography of Africa states that it was a barren region “both as respects to the nature of the soil, and the moral conditions of the inhabitants.”

When a century later Australian, Canadian, Nigerian, Kenyan, or Trinidadian writers would remark that their colonial educations had familiarized them with English landscapes or misty autumns to the exclusion of the ecologies or climates of their own regions, they were probably legatees to an educational and textbook culture initially pioneered in Ireland in the early 1800s.

The emergence of the modern university system and the English department in Ireland must be viewed in these wider national and imperial contexts. Trinity College, which remains Ireland’s most internationally prestigious university, was founded in 1592 at the time of the Tudor plantations and would remain well into the twentieth century what David Dickson has called “the ‘central fortress’ of ancien regime values and Anglican power” (Reference Dickson, Dickson, Pyz and Shephard187). Protestant dominance of the professions in Ireland was, Dickson notes, at its apogee in the 1850s, and in the mid-nineteenth century Trinity competed strongly with other British universities in terms of securing clerkships in the Indian Civil Service (ICS), coming second only to Oxford in competitions for imperial opportunity. When in the 1850s it was decided that recruitment to the ICS should be by competitive examination, Trinity responded promptly and in 1855 appointed William Wright to the chair of Arabic and in 1859 a lecturer, later in 1862 professor, of Sanskrit, Rudolf Thomas Siegfried. R. B. McDowell and D. A. Webb comment that Trinity “was quick to see that the new category of ‘competition-wallah,’ even if looked down on at first by old hands nominated by personal influence, provided a new outlet for Dublin graduates seeking an employment that was at once adventurous and commensurate with their abilities and social status.” As a result, “Trinity sent a steady stream of graduates to India as long as British rule lasted” (Reference McDowell and Webb232–34).

Against the opposition of the Catholic episcopacy, secular nondenominational colleges were opened in Belfast, Cork, and Galway in 1845, which commenced teaching as associative members of the Queens University of Ireland in 1849, as the country was devastated by famine. A separate Catholic university was opened in Dublin in 1854, but without a royal charter to endorse its degrees and suffering from serious underfunding it fared poorly with government-sponsored rivals. In 1882, it was reorganized to become University College Dublin (UCD) and became a constituent member of the Royal University of Ireland, a revised version of the Queens University system. If the Famine devastated the poorest classes in Ireland especially and accelerated chronic migration outward for decades to follow, the same epoch also consolidated Irish Catholic middle-class professional formation. Soon, the new Queens and later Royal colleges were also competing to take advantage of imperial opportunity, turning out graduates to secure ICS clerkships or to work in the Indian medical service or as engineers to meet the demands of Irish and Indian railway booms. S. B. Cook argues that after 1870 Irish competitiveness in ICS exams suffered when Sir Charles Wood and Lord Salisbury reformed the recruitment process to improve the quality of Indian administration. Both men, Cook argues, were sincere in their improving intentions, but nevertheless “they shared the mid-Victorian belief that English gentlemen were the best conceivable imperial guardians. Both men loathed what they regarded as the tradesmen’s instincts and infinite insecurities of youth. But they also doubted the ability of the Irish either to rule themselves or govern others” (Reference Cook514). The reduction in Irish recruitment for Indian positions coincided, then, with a period of increased domestic agitation in Ireland – the Land Wars, the Home Rule crises – and the same universities that contributed to training Irishmen for empire also educated an emergent Irish middle class that would rule the Irish Free State after 1921.

The emergence of English literature as a distinct subject of university study coincided with the appointment of Edward Dowden to the post of Chair of English in Trinity College in 1867. As histories of the discipline make clear, this development represented a wider secular and modernizing turn in Western university education, one that would eventually see the previously dominant Classics become in time a relatively minor discipline and which brought the study of national literatures to the fore. Though part of its mission might be to afford a humanist corrective to the competitive individualism of laissez faire capitalism, in universities committed to securing British national and imperial greatness the study of English inevitably meant that the new discipline acquired its own ideological cast.1

Dowden, for example, was a committed Irish unionist and devotee of the British Empire. Franklin Court claims “Dowden was an outspoken political conservative who distrusted and feared democracy as a great class leveler, but in Dublin particularly, the spectre of Paddy with a torch standing on his doorstep could seem real.” Nevertheless, he adds, “Dowden was not alone among late-century English professors in his ethnocentric support for an idealized historical continuum and in his desire to curtail democratic reform efforts. Although the heritage of Burkean conservatism was more evident in Dowden than in other late-century English professors, the mainstream tradition of literary study in England generally had become tacitly more nationalistic and conservative” (Reference Court154–55).

Dowden had written an authoritative Life of Shelley (1886) before his Trinity appointment and would later write Robert Browning (1904), but his reputation rests primarily on his many studies of Shakespeare, especially Shakespeare: His Mind and Art (1875). Dowden’s Shakespeare offers the playwright as an epitome of Protestant manliness, sound business sense, and liberal tolerance, the antithesis to the mercurial Celtic flightiness then popularized in Celtic and Saxon racial discourses. Though receptive to international intellectual currents, Dowden was stubbornly hostile to the later nineteenth-century Irish Literary Revival, viewing with suspicion anything Irish that would distinguish itself from a common Britishness.2 He was on friendly terms with William Butler Yeats’s family and an admirer of the young Yeats’s poems, but refused to write on Irish writers or subjects and refused permission for his own poetry to be published in a “specially Irish anthology” (Reference LongleyLongley 30). In his later years, Dowden campaigned for the Irish Unionist Alliance against Irish Home Rule and in 1908 took charge of the Irish branch of the British Empire Shakespeare Society (BESS) that had previously been presided over by John Pentland Mahaffy, the distinguished Trinity classicist and onetime tutor to Oscar Wilde. The importance of the English Renaissance period – then celebrated as the “Golden Age” of empire, Shakespeare, and the Globe Theatre – was reflected also in the works of other early chairs of English (or History and English Literature as several were titled) in Irish universities. Frederick S. Boas, Chair of History and English in Queens University Belfast, published many books on Renaissance drama, and Thomas William Moffitt, who became chair of History and English in Queen’s College Galway in 1863, published Selections from the Works of Lord Bacon (1847).

James Joyce was born in 1882, the same year that the Catholic university became University College Dublin. He received his early education in Clongowes Wood College, Co. Kildare, a Jesuit private boarding school opened in 1814 and one of Ireland’s premier elite Catholic schools modeled on English equivalents such as Eton and Harrow. Clongowes had a strong record in training its students for imperial and missionary service and cultivated an English-style sporting ethos that included cricket, association football, lawn tennis, and cycling. Thanks to his father’s improvidence, Joyce’s education differed from that of this elite because he had later to transfer to Belvedere College, Dublin, another elite though somewhat less prestigious Jesuit school. In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), the young Stephen Dedalus’s alienation from Clongowes’s muscularly Catholic and imperial ethos is everywhere evident. Stephen is physically timid and lacks interest in sports; his father has Fenian and Home Rule sympathies; his family fortunes are in decline; he loses his religious faith and becomes sexually dissolute: all these things bring the young Dedalus into intellectual conflict with the Clongowes mission to educate cultivated Irish Catholic “gentlemen” with the social poise and assurance to match their Etonian English counterparts. Joyce’s self-exile from Ireland after 1904 meant that he became an émigré distanced from the Home Rule Catholic elite with which he was educated or from the more militant Sinn Féin nationalist middle class as it assumed state power after the War of Independence and the establishment of the Free State in 1921. Nevertheless, Ulysses clearly reflects much of the historical resentment of England and indeed the high ambition of this Catholic bourgeoisie in the era of its radical self-assertion; Joyce worked on that novelistic epic throughout the violent years that led up to the foundation of the Irish Free State.

In the final section of Portrait, as Stephen makes his way toward his university lectures in Earlsfort Terrace, he passes “the grey block of Trinity on his left, set heavily in the city’s ignorance like a great dull stone set in a cumbrous ring” and feels it pull his “mind downward” (Reference Joyce and DeaneJoyce 194). Passing the Trinity entrance, Stephen feels himself “striving this way and that to free his feet from the fetters of the reformed conscience” and observes the “the droll statue of the national poet of Ireland” (Reference Joyce and Deane194). To Stephen, the monument to Thomas Moore positioned just outside Trinity College is pitiable, but he regards the edifice with more sorrow than anger because “though sloth of the body and the soul crept over it like unseen vermin,” the statue “seemed humbly conscious of its indignity.” As Stephen enters Earlsfort Terrace, site of University College Dublin, he reflects, “it was too late to go upstairs to the French class” (Reference Joyce and Deane199). This lateness for French conveys his sense of being severed from the European continent, and Stephen sighs that his own poor knowledge of Latin and his nation’s tardiness would always render him “a shy guest at the feast of the world’s culture” (Reference Joyce and Deane194).

Too late for French instruction, he makes his way to meet the Dean of Studies in one of Portrait’s much-cited set pieces. Listening to the English Jesuit dean speak, Stephen reflects:

The language in which we are speaking is his before it is mine. How different are the words home, Christ, ale, master, on his lips and on mine! I cannot speak or write these words without unrest of spirit. His language so familiar and so foreign, will always be for me an acquired speech. I have not made or accepted its words. My voice holds them at bay. My soul frets in the shadow of his language.

In these passages, Joyce deploys Dublin’s topography to illustrate a history of Irish educational and aesthetic formation that has shaped Stephen but which he must overcome if he is to liberate himself as an artist and “to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race” (Reference Joyce and Deane276). The “dull grey stone” of Trinity College pulls Stephen’s “mind downwards.” Protestantism’s “reformed conscience” does not represent for him the claims for individual freethinking and tolerance, which it claimed for itself, but merely another foot-fetter on his own people. Moore’s statue with its “shuffling feet” and “servile head” symbolizes not some monumental Irish poetic achievement but a subservient sloth. However, because it is “humbly conscious of its indignity,” the monument also painfully registers the centuries of oppression that bred this abased condition. If French culture is beyond his reach, English culture, “so familiar and so foreign,” Stephen admits only as “an acquired speech,” a colonially imposed language his voice “holds at bay” and within which “his soul frets” like a captured thing.

As is now widely recognized, in Portrait Joyce expresses a colonial and postcolonial predicament. Others elsewhere – Chinua Achebe in Nigeria, Ngũgĩ wa’ Thiong’o in Kenya, C. L. R. James and V. S. Naipaul in Trinidad, Derek Walcott in Saint Lucia, Jamaica Kincaid in Antigua – would describe their own childhood schoolroom encounters with the English language and literature in British-centric education systems. These formative experiences usually nurtured lifelong affections for English literature but also the sense of an early indenture into an inheritance not merely not one’s own but that of one’s imperial master. The language options open to these writers varied but a sense of the English language and English literature as both franchise and fetter to self-expression pulsates through the works they created.

Still, there is reason not to overplay Foucauldian or Althusserian conceptions of disciplinary technologies or subject interpellations that control subjectivity so completely as to leave little room for resistance. There are distinctions between constriction and complete constructivism. The importance of the national school system and of university education to the anglicization of Ireland and the cultivation of imperialist mentalities cannot be doubted. However, as Joyce’s situation illustrates, Irish subjects could obviously bring a critical consciousness to bear on the institutions that inculcated such subject formation and many of Joyce’s predecessors and contemporaries responded to their colonial situations more militantly than Joyce did. Wolfe Tone and Robert Emmett, founding figures for militant republicanism, Thomas Davis and John Mitchel, leaders of the Young Ireland cultural nationalist movement, and Isaac Butt and John Redmond, leaders of the Home Rule movement, were all Trinity College students. Leading Catholic republican or nationalist figures including James Fintan Lawlor, a radical Young Irelander, James Stephens, a founder of Fenian Brotherhood, Frank Hugh O’Donnell, MP and anti-imperialist, and Patrick Pearse and Thomas McDonagh, leaders of the Easter 1916 insurrection, all attended Catholic-associated private schools or universities. Many of the most prominent figures in Irish political movements had very little formal schooling. Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, a prominent Fenian, spoke Irish only at home, learned English in a local school, saw his father die of fever in the Famine and his mother and siblings emigrate to America, and found early employment in a relative’s hardware store. Michael Davitt’s Irish-speaking parents were evicted from their Mayo tenant farm in 1850 and then emigrated to Lancashire, where Michael was homeschooled but lost an arm in a factory accident, aged eleven. Born to Irish emigrant parents in a slum district of Edinburgh, James Connolly, founder of the Irish Citizen Army, received minimal formal education at a local Catholic school. He went to work early before joining the British Army, where he may have served in India and did in Ireland, later becoming a trade unionist, socialist, and Irish separatist. Fanny and Anna Parnell, sisters to the charismatic Home Rule leader Charles Stewart Parnell, were born on a landlord’s estate in Wicklow and enjoyed a comfortable upbringing but had very little formal education beyond what they obtained from the family library. The struggles against a colonial educational formation of which Joyce writes so searchingly in Portrait would speak to many young colonized subjects across the British Empire. However, until the universities became somewhat more accessible to women and the working classes after World War II, the educational experiences described by Joyce in Portrait applied only to a tiny percentage of such subjects.

How much did the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1921 do to decolonize the Irish university system or the subject of English more specifically? In the absence of proper departmental histories, the question is impossible to answer in any real detail, though one can hazard broad observations. The partition of Ireland after 1921 meant that the decolonization was partial, and the two new states compounded some of the less progressive features of the colonial system. In the new Northern Irish state especially, where a majoritarian Protestant unionist establishment took power against the backdrop of a slowly contracting British Empire and the emergence of anticolonial national movements on many continents, the colonial and imperial dimensions of higher education may have hardened rather than softened. In both states, primary and secondary education largely remained divided, as it had in nineteenth-century Ireland, along sectarian Catholic and Protestant lines. In the words of recent scholars, the new Ministry for Education in Northern Ireland sponsored “a very clear determination to create a system which would ensure allegiance to the Empire and protect against dissention (e.g. the explicit promotion of elements of Irish culture, history and language)” (Reference O’Toole, McClelland and FordeO’Toole, McClelland, Forde, et al. 1030). In a subsection titled “Loyalty,” the Lynn Committee report of 1923 commissioned to establish Northern Irish educational policy stipulated that all state-funded teachers were to take an oath of allegiance to the British Crown and “no books were to be used in the classroom ‘to which reasonable objection might be entertained on political grounds’” (Reference O’Toole, McClelland and FordeO’Toole, McClelland, Forde, et al. 1030). The report found no justification for any special status for the Irish language and “decided to treat it like any other language, precluding its teaching henceforth below standard five (11 years old) in line with the practice of other ‘foreign’ languages” (Reference O’Toole, McClelland and Forde1030). In this repressive context, the Catholic church refused in the 1920s to transfer their schools to the authority of the Northern state and retained patronage of them, a decision which, the same authors conclude, “proved crucial in sustaining the identity of a coherent Catholic community through to the present day” (Reference O’Toole, McClelland and Forde1030).3

South of the border, the Irish Free State deemed schools and schoolchildren crucial to the cultivation and consolidation of a new national identity. By the 1920s, Ireland was a much-anglicized society, and the new government viewed itself as striving to create or restore a strong sense of “Irishness” in the teeth of a far more powerful British culture in an era of wide-reaching media technologies and culture industries. Thus, the new state established the revival of the Irish language and culture as a priority. Southern policy stipulated that schools were to devote a minimum of one hour every day to instruction in Irish, while no time stipulations applied to other subjects. The Catholic church had already secured considerable control over the southern Irish education system in the post-Famine era, and partition further consolidated this. “The State-Church alliance in education was largely a pragmatic and symbiotic relationship, with the Free State benefitting from the financial resources and reputational legitimacy of the Catholic Church in the provision of educational and other services” (Reference O’Toole, McClelland and FordeO’Toole, McClelland, Forde, et al. 1023).

Leah O’Toole et al. also note that the national school curriculum devised in 1900, before partition, was clearly gendered and specified that “the average primary schoolgirl, when she assumes the position of housewife” ought to be able to “perform the ordinary culinary and washing operations that may appertain to her position” (Reference O’Toole, McClelland and Forde1028). The Victorian conception of girls as miniwives and mothers-to-be persisted after partition. In the 1922 and 1926 curricula in the South, cookery and laundry work were placed center stage for girls only, and every girl was to receive three hours of needlework instruction per week. In the North, too, the 1923 Lynn Report stressed that girls be taught practical skills such as cookery, laundry-work, and household management and that boys learn woodwork (Reference O’Toole, McClelland and FordeO’Toole, McClelland, Forde, et al. 1028–29).

One of the more famous school poems of the era, William Butler Yeats’s “Among School Children,” opens with the poetic persona ruminatively visiting a Catholic girls’ school and ruefully pondering the children’s youth, his own aging, and the mysteries of beauty:

Yeats may ponder whether “the best modern way” can produce the natural beauty of the aristocratic Maud Gonne, and he self-deprecatingly presents his own senatorial role in the Free State as he imagines the children might view him. However, the poem’s detached patrician voice contemplating the idea of beauty among nuns and schoolgirls – described in passing as lower class “paddlers” to Maud Gonne’s “swan” (122) – probably reflects something also of the wider hauteur of the new elites in both Irish states with regard to the children of the poorer sort and their education. In other words, the Yeats figure in “Among School Children” is much more preoccupied with his own memoires and cultural ideals than with the actualities of the schoolgirls’ lives or aspirations. The Irish Free State, later Republic, might be accused of a like form of detached idealism, one that prioritized education as nation-building at the expense of any real consideration of the realities of the poor, most destined for manual labor at home or the emigrant boat to Britain or the United States.

Himself deemed only a moderate student in his schooldays, and someone who never attended university, Yeats’s “Among School Children” was written after the poet-senator’s visit in 1926 to St. Otteran’s in Waterford City, a Sisters of Mercy convent founded only a few years earlier in 1920. The school practiced Montessori methods that stress a unity of intellectual and practical activities and creative self-expression. Yeats’s poem conveys a like ideal when it rounds off with a final swerve stanza that favors an organicist mode of cultivation where: “The body is not bruised to pleasure soul, / Nor beauty born out of its own despair, / Nor blear-eyed wisdom out of midnight oil” (123). These are admirable sentiments, but the realities of Irish education at all levels were mostly remarkably different. For much of the twentieth century, in both the more religious and secular schools, discipline, especially for the lower classes, was harsh or openly violent, educational achievement was determined by rigid exam systems, class and gender stratifications were institutionalized, and university remained restricted, until the 1970s and 1980s, to small minorities. In recent years, commissions to investigate the “industrial schools,” a euphemism for reformatory institutions for juveniles, have attested to an extraordinary history of physical, mental, and sexual abuse of minors. Yeats’s views on education may have been more enlightened than those of many of his contemporaries, but his views on modern democracy, gender, class, and elite rule were mostly, like those of the new elites more widely, very nineteenth-century.4 The more authoritarian, eugenicist, and fascistic notes sounded in his social and poetical works from the 1930s onward caution against any simple notion of linear social or educational progress as modern Ireland transitioned from Dowden’s world of Victorian Ascendancy domination into the turbulence of the mid-twentieth century.

The brief history of the English department’s place in the wider colonial history of Irish education roughly sketched here can in some respects be considered typical. In all regions of the British Empire, the teaching of English literature cultivated a sense of “Britishness” that was always classed, racialized, and gendered. In Ireland, as elsewhere, that process produced mixed results, and the state education systems that emerged out of the anti-imperial independence struggles retained many assumptions and features that had informed the colonial-era system even if they “decolonized” others. It would be interesting to know in more detail to what extent and in what ways university English departments in Ireland, north and south, changed – in terms of ambitions, personnel, curriculum, and modes of teaching – in the decades after the 1920s but, as remarked at the outset of this essay, there are few studies that document such changes.