“Hopewell” is an expansive cultural phenomenon that engaged small-scale societies scattered from the Great Plains to the Chesapeake Bay, from the Canadian Shield to the Gulf Coast, during the Middle Woodland period (ca. AD 1–400). Traditionally, archaeologists identify Hopewellian engagement by the presence of a small suite of highly distinctive artistic crafts including bicymbal copper earspools, metal-jacketed panpipes, platform effigy pipes, and diagnostic styles of lithic tools and ceramics (Griffin Reference Griffin and Griffin1952, Reference Griffin1967; Seeman Reference Seeman and Townsend2004). Middle Woodland societies across the Midwest, Midsouth, and Gulf Coast had variable settlement-subsistence systems and social organizations and engaged with Hopewell ceremonialism at different times and in different ways (see Abrams Reference Abrams2009; Wright Reference Wright2017). Hopewellian groups, most notably in Ohio, are known for the construction of massive earthen monuments—mounds of various scales and ditch-and-embankment enclosures often of geometric forms, sometimes aligned to solar and lunar standstills. Likewise, they are renowned for the diverse and ornate works of art that were interred within these mounds (Willoughby Reference Willoughby1916). The focus of our analysis, the Scioto Hopewell (AD 1–400), located in the central Scioto Valley (CSV)Footnote 1 of southern Ohio (Greber Reference Greber1991), were forager-farmers, utilizing the suite of cultigens and domesticates known as the Eastern Agricultural Complex (EAC; Carr Reference Carr, Troy Case and Carr2008a:79–90; Wymer Reference Wymer and Seeman1992, Reference Wymer and Pacheco1996, Reference Wymer, Dancey and Pacheco1997), living in sedentary hamlets on floodplains (Dancey and Pacheco Reference Dancey and Pacheco1997; Ruby et al. Reference Ruby, Carr, Charles, Carr and Case2005), organized in nonhierarchical communities (Byers Reference Byers2004, Reference Byers2011; Case and Carr Reference Case and Carr2008; Coon Reference Coon2009; Greber Reference Greber1979).

Hopewellian material symbols—including mica cutouts, miniature and hypertrophic copper celts, obsidian spearpoints, sheet copper headdresses, carved bone whistles, and so on—were of various media, and although sometimes composed of long-utilized materials or occasionally employing preexisting styles, they were of unprecedented diversity, technical skill, and quantity. Many of these media were exotic raw materials—pipestone, obsidian, silver, copper, galena, mica, Knife River chert, marine shell—acquired over the greater part of eastern North America. These materials gained importance not only by virtue of the distance traveled for their acquisition but referentially, as “metaphorical connections to the earth, sky, and directionality” (Seeman Reference Seeman and Townsend2004:62). Hopewellian art is thematically dominated by animal motifs, also incorporating ancestral and other symbolism, that were employed in a media-specific fashion with no pervasive style (Seeman Reference Seeman and Townsend2004:64).

Scioto Hopewell peoples used these highly crafted arts in a complex ceremonialism. Hopewellian art was utilized in performance, as evinced by sculptural examples of people dressed in zoomorphic shamanic costumes (Carr Reference Carr, Troy Case and Carr2008b:180–199; Cowan Reference Cowan and Pacheco1996:134; Giles Reference Giles, Redmond, Ruby and Burks2019; Seeman Reference Seeman and Townsend2004:61; see also Dragoo and Wray Reference Dragoo and Wray1964) and human burials arrayed in elaborate regalia (e.g., DeBoer Reference DeBoer2004). Similarly, art may have functioned in tableaux narrating ritual dramas (Carr and Novotny Reference Carr, Novotny, Hargrave, Schermer, Hedman and Lillie2015). Art also served as gifts among human and other-than-human beings (Carr Reference Carr, Troy Case and Carr2008b:255–262; Seeman Reference Seeman and Townsend2004:62–65). Hopewellian art had “social lives” (Penney Reference Penney2004:50) or personhood (Seeman et al. Reference Seeman, Nolan and Hill2019:1095), often being intentionally burned, broken, or “killed” before being interred and eventually mounded over.

The prominence of the communal construction of ritual landscapes (Bernardini Reference Bernardini2004) and prevalence of material symbols (Seeman Reference Seeman and Townsend2004:59; cf. Spielmann Reference Spielmann and Lynott2009:179) in Scioto Hopewell society make the lens of ritual economy especially apropos. This framework allows us to explore the relationships of these elements of Scioto Hopewell ceremonialism to subsistence, settlement, and social organization (Miller Reference Miller2015:136). Here we focus specifically on the role of craft production, defined as “the manufacture of items unrelated to, or at a level of intensity beyond, the subsistence needs of the ‘average’ household” (Pluckhahn et al. Reference Pluckhahn, Menz, O'Neal, Price and Carr2018:115). Crafting, at the scale documented, had the potential to reorganize the subsistence economy and to restructure social relations. Yet the organization of craft production is poorly documented and understood (Wright and Loveland Reference Wright and Loveland2015:149). Here we argue that the North 40 site (33RO338), situated just outside the Mound City Group (33RO32) earthwork complex, is the best-documented Scioto Hopewell craft production site. We analyze the organization of Scioto Hopewell craft production through the framework of ritual economy to demonstrate how the organization of production outside of the household or domestic contexts impacted society more broadly and shaped larger-scale structures in Scioto Hopewell society.

Ritual Economy and Craft Production in Small-Scale Societies

Increasingly, archaeologists are using “ritual economy” as an analytical lens to approach a variety of social phenomena (e.g., Wells and Davis-Salazar, ed. Reference Wells and Davis-Salazar2007; Wells and McAnany Reference Wells and McAnany2008). Ritual economy refers to the dialectical relationship between ritual and economy: on the one hand, referencing the necessary economic considerations and consequences of engaging in particular rituals and, on the other, highlighting the influence of ritually mediated values, worldviews, and meanings on economic practices (Miller Reference Miller2015:124; Wells Reference Wells2006:284; Wells and Davis-Salazar Reference Wells, Davis-Salazar, Wells and Davis-Salazar2007:3). Some scholars dichotomize these relationships heuristically as the “economics of ritual” and the “ritual of economy” (Watanabe Reference Watanabe, Wells and Davis-Salazar2007:301). Ritual economies often operate fundamentally differently in small-scale societies due to limited population densities and the lack of political centralization (Spielmann Reference Spielmann2002, Reference Spielmann, Wells and McAnany2008). Small-scale societies are those that contain several hundred to several thousand people united by diffuse political structures organized around kin groups, wherein “ritual and belief define the rules, practices, and rationale for much of the production, allocation, and consumption” (Spielmann Reference Spielmann2002:203). This leads some scholars to suggest that discussion of social dynamics in small-scale societies inherently involves consideration of ritual economy (Miller Reference Miller2015:125; Spielmann Reference Spielmann and Lynott2009:179; Watanabe Reference Watanabe, Wells and Davis-Salazar2007:313).

Here we focus on the economics of ritual, one aspect of which is the production of crafts that are used in ritual and whose creation is also often ritualized (Miller Reference Miller2015; Wright and Loveland Reference Wright and Loveland2015). Craft production can be organized in variable ways (Brumfiel and Earle Reference Brumfiel, Earle, Brumfiel and Earle1987:5; Childe Reference Childe1950:7–8; Costin Reference Costin and Schiffer1991:4; Spielmann Reference Spielmann2002:202). Archaeologically, craft production is identified by the recovery of “raw materials, debris, tools, and facilities associated with production” (Costin Reference Costin and Schiffer1991:19). Spielmann (Reference Spielmann2002:198, 201–202) suggests that community specialization—households within a community specializing in the production of a specific craft—is the prevalent organizational strategy of craft production among small-scale societies worldwide (see also Malinowski Reference Malinowski1935:22). Yet she (Spielmann Reference Spielmann2002:202, Reference Spielmann and Lynott2009:183) notes a variant in some societies where ceremonial centers, rather than residential contexts, are the loci for aggregation and craft production. Here, artisans and their productive activities are carried out in corporate or communal facilities—workshops—embedded in ritual contexts, outside the domestic realm, and often associated with other religious and mortuary activities. Workshops are relatively unknown from small-scale societies, being far more common in complex societies. The restriction of craft production to ceremonial precincts may be a function of ritual practitioners exercising control over the materialization of ideology, logistical exigencies arising from dispersed patterns of residential settlement, or even the need to “deal with” the power inherent in certain raw materials and ritual paraphernalia (DeMarrais et al. Reference DeMarrais, Castillo and Earle1996; Seeman et al. Reference Seeman, Nolan and Hill2019; Spielmann Reference Spielmann and Lynott2009:183).

The production of objects and spaces in preparation for ritual is often an actively ritualized process in and of itself (Costin Reference Costin, Wright and Costin1998:5; Miller Reference Miller2015:137; Spielmann Reference Spielmann2002:200; Wright and Loveland Reference Wright and Loveland2015). Inherent in the creation or transformation of objects imbued with power and meaning, whose production is divorced from the domestic sphere, is the fact that the practices of creation are themselves spiritually powerful. It follows, then, that the transformation of these raw materials into crafts may be restricted within a population beyond just those possessing the prerequisite skill. In fact, in small-scale societies, the warrant to produce ritual paraphernalia may be gendered or restricted to a few individuals and may require specific esoteric knowledge (Spielmann Reference Spielmann2002:200, Reference Spielmann and Lynott2009:180). Further, in places of production set aside from the domestic sphere, the places themselves may be imbued with ideological or religious significance (Spielmann Reference Spielmann2002:200).

Scioto Hopewell Craft Production

Craft production among Scioto Hopewell peoples was a complicated affair involving three essential parts: (1) the acquisition of a multitude of exotic raw materials (e.g., pipestone, obsidian, silver, copper, galena, mica, Knife River chert) from distant sources; (2) the transformation of these materials into sacred and symbolically charged objects; and (3) the varied rituals, exchanges, and performances utilizing these objects before their deliberate deposition in shrines and mortuary contexts. These parts have received uneven scholarship. Researchers (e.g., Emerson et al. Reference Emerson, Farnsworth, Wisseman and Hughes2013; Hill et al. Reference Hill, Seeman, Nolan and Dussubieux2018; Hughes Reference Hughes, Charles and Buikstra2006) have made much progress identifying sources of exotic materials. Their findings are important in building and interrogating models for how and with and by whom these materials were obtained (Bernardini and Carr Reference Bernardini, Carr, Carr and Case2005:633–635; Carr Reference Carr, Carr and Case2005a; Spielmann Reference Spielmann and Lynott2009:180). Similarly, analysis and interpretation of ritual and mortuary contexts have led to much insight into the iconography and the religious significance of these crafts (Carr and Case Reference Carr, Case, Carr and Case2005; Carr et al. Reference Carr, Weeks, Bahti, Troy Case and Carr2008; Giles Reference Giles and Alt2010; Hall Reference Hall, Brose and Greber1979) and the nature of the ceremonial events preceding their deposition (see Carr Reference Carr, Carr and Case2005a, Reference Carr, Troy Case and Carr2008b). Yet our understanding of the production of these crafts has lagged behind (Wright and Loveland Reference Wright and Loveland2015:138–139).

Although the nature of Scioto Hopewell craft production has been explored through analyses of numerous finished products, direct evidence of crafting has been elusive. The rarity of crafting debris at domestic sites leads most researchers to conclude that craft production took place in or near Scioto Hopewell earthworks (e.g., Coon Reference Coon2009:57; Spielmann Reference Spielmann2013:149). Both copper earspools (Ruhl and Seeman Reference Ruhl and Seeman1998) and textiles (Carr and Mazlowski Reference Carr, Mazlowski, Carr and Neitzel1995) seem to have styles corresponding to earthwork sites, suggesting localized centers of production. Spielmann (Reference Spielmann and Lynott2009:183, see also Reference Spielmann2013:149–150), noting that some earspools are assembled of two stylistically different halves and that some earspool pairs are unmatched (Greber and Ruhl Reference Greber and Ruhl1989; Ruhl and Seeman Reference Ruhl and Seeman1998), suggests that they were made by different craftspeople, perhaps in communal workshops. Some textiles contain different kinds of yarn, suggesting either that multiple artisans worked together or that they were at least produced in a facility with a variety of available yarn (Wimberley Reference Wimberley and Drooker2004; see also Spielmann Reference Spielmann and Lynott2009:184, Reference Spielmann2013:150). Conversely, Penney suggests that

a relatively small group of artists created hundreds of individual pipes closely conforming in scale, technique, style, and image, even to the extent that the Mound City and Tremper sets include pipes that virtually duplicated their effigy in pose, attitude, and detail [Reference Penney2004:52; see also Minich Reference Minich2004; Penney Reference Penney1988].

To date, archaeologists have identified few compelling examples of craft production sites in the central Scioto Valley region (see Coon Reference Coon2009:57; Wright and Loveland Reference Wright and Loveland2015:138–139). For decades, the seven wooden-post structures within the enclosure at the Seip Earthworks (33RO40) were interpreted as craft production workshops (Baby and Langlois Reference Baby, Langlois, Brose and Greber1979). While the associated artifact assemblages were initially thought to be the residue of activities that took place inside the structures, reanalysis identified these materials as secondary deposits included in low mounds overlying the structures (Greber Reference Greber2009a). Thus, Greber (Reference Greber2009b:171, ed. Reference Greber2009) reinterpreted these structures as places of repeated rituals over the course of generations. Similarly, the discovery of a single large pit (Feature 9) containing stacked clusters of alternating ceramic sherds and cut mica sheets at the Hopeton Earthworks (33RO26) was briefly interpreted as evidence of craft production (Lynott Reference Lynott2014:122–123). Yet the pit was primarily filled with utilitarian refuse, leading to the interpretation that these materials were instead the residue of a ceremonial event (Lynott Reference Lynott2014:123; Spielmann Reference Spielmann and Lynott2009:186–188). Finally, a season of excavation at the Datum H site at Hopewell Mound Group (33RO27) gathered intriguing data, including nearly 250 bladelets and a small amount of mica and obsidian (Pacheco et al. Reference Pacheco, Burks and Wymer2012). Yet no structure has been documented, and, to date, artifact analyses have yet to be completed, limiting any conclusions regarding the presence of craft production at the site.

Though little evidence of craft production has been reported in the Scioto River Valley, Miller (Reference Miller2014, Reference Miller2015) documented craft production through a microwear analysis of bladelets at the Fort Ancient Earthworks in the Little Miami River Valley of southwestern Ohio. He (Reference Miller2015:135–136) documented relatively intense craft production in three areas based on bladelet use-wear and crafting in a fourth area evidenced by worked exotic materials. But the limited direct evidence—production loci and debris (Costin Reference Costin and Schiffer1991:18–19)Footnote 2—restricts insights into how craft production was organized here. Comparisons between this site and those in the CSV must be qualified given the presence of habitations (Connolly Reference Connolly, Dancey and Pacheco1997; Lazazzera Reference Lazazzera, Connolly and Lepper2004), its differing physiographic position and corporate-ceremonial context (as a hilltop enclosure), and the markedly larger scale of acquisition of exotic raw materials and overall production and consumption of crafts in the CSV. A production area for lithic objects has also been located and analyzed in the Little Miami River Valley, near the Turner Earthworks (Nolan et al. Reference Nolan, Seeman and Theler2007), as well as similar lithic production sites near the Flint Ridge quarry in east-central Ohio (Lepper et al. Reference Lepper, Yerkes and Pickard2001; Mills Reference Mills1921). Despite these examples, the close clustering of earthwork centers (Ruby et al. Reference Ruby, Carr, Charles, Carr and Case2005:160) in the CSV suggests that the logistics of craft production could have been organized differently, with, for example, centralized crafting “schools” or sites of production serving multiple residential communities or, conversely, specialized production centers distributed across multiple residential communities.

This analysis of the materials recovered from the North 40 site demonstrates that it is now the best-documented Scioto Hopewell craft production site. The material remains represent the raw material and debris (e.g., chert debitage, mica, and copper), tools (e.g., chert and crystal quartz bladelets, bone perforators, and an obsidian unifacial tool), and facilities (structures and refuse pits) of craft production. Specifically, the patterned deposition of debris in aligned pits and the architectural scale of the sampled building (Structure 1) make clear that this was a locale of craft production. Some of the materials (e.g., ceramic vessels, EAC seeds, and a ceramic pipe) represent the residue of ritual activities intertwined with craft production. The North 40 site—following geophysical survey, small-scale excavation, and analyses of artifacts associated with three pit features and a large timber-post structure (Structure 1)—illuminates the nature and organization of craft production among Scioto Hopewell peoples.

The North 40 Site

The North 40 site is an open occupation located about 300 m north of the Mound City Group, a renowned Hopewellian mound-and-earthwork complex consisting of at least 25 mounds surrounded by an earthen embankment enclosing approximately 6.5 ha (Figure 1; Brown Reference Brown2012:15, 31; Lynott and Monk Reference Lynott and Monk1985:3; Squier and Davis Reference Squier and Davis1848). Both sites are located near the edge of a Wisconsinan-age glacial outwash terrace that drops precipitously to the active floodplain and western bank of the Scioto River about 10 m below. The proportion of black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos), and other secondary growth species represented in the charcoal assemblage suggests significant human modification of this area, including clearing some portion of the old-growth forest (Leone Reference Leone2013:5; see also Wymer Reference Wymer and Pacheco1996:44–45, 47). The North 40 site consists of at least three timber-post structures (identified through magnetic gradient surveys) and a series of related pit features (Figure 1). Structure 1 and three nearby pit features (Pits 1, 2, and 3) were sampled in excavations, revealing that these pits were filled with refuse indicative of craft production and ceremonial gatherings.

Figure 1. North 40 site magnetometry survey results and the proximity from North 40 site to Mound City. (Color online)

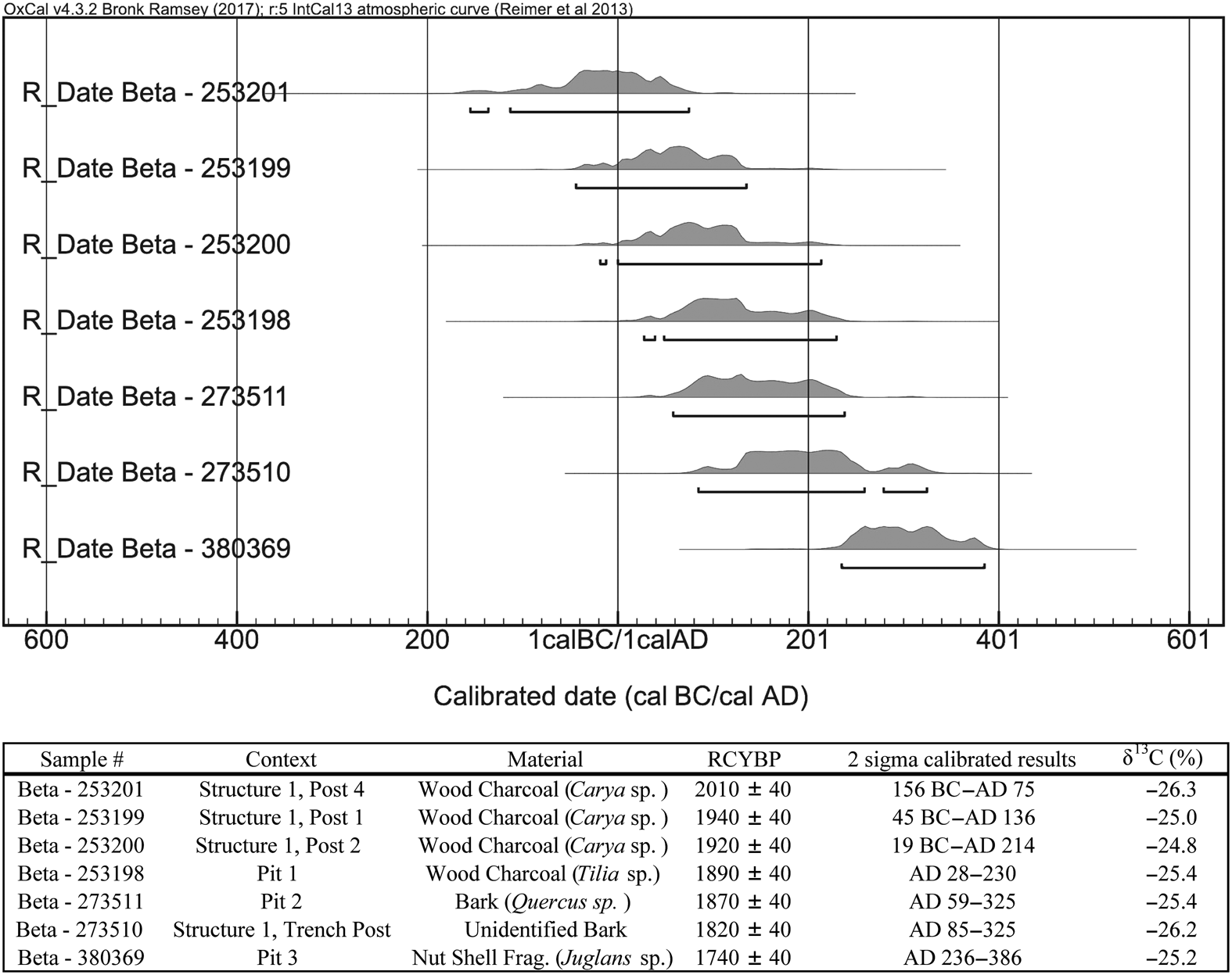

The North 40 precinct hosted activity across most of the Middle Woodland period (AD 1–400). Seven samples were submitted for accelerator mass spectrometry radiocarbon dating: four samples from postholes of Structure 1 and one sample from each of the three pits (Figure 2). The range of dates reflects a persistent and protracted, if episodic, occupation. A series of pairwise T-tests (α = 0.05) across the set demonstrates that there is no significant hiatus in the occupation. The summed probabilities place the occupation between cal AD 5–AD 220 (68% probability), or cal 51 BC–AD 376 (95% probability; analyzed with Stuiver et al. Reference Stuiver, Reimer and Reimer2019). These dates are contemporaneous with the use of Mound City (Brown Reference Brown2012:45–53), and the site's occupation may well have traced the ebb and flow of ceremonial activities at Mound City.

Figure 2. Distribution and description of accelerator mass spectrometry dates from the North 40 site.

History of Research

Archaeologists first discovered the North 40 site in the 1960s through surface finds of diagnostic Hopewell bladelets (then named the “Drill Field” site). In 1982, Mark Lynott and a team from the National Park Service's Midwest Archeological Center completed a surface survey and limited excavations and concluded that the “relatively low density of artifacts” they collected represented a series of intermittent, short-term camps. They suggested that “the majority of archaeological remains [were] located in the plowzone” (Lynott Reference Lynott1982:4, 7; Lynott and Monk Reference Lynott and Monk1985:20).

A team from Hopewell Culture National Historical Park returned for additional research from 2007 to 2009 and in 2013 and 2017. In 2007, staff conducted a magnetic gradient survey using a Geoscan FM256 fluxgate gradiometer and tested discovered anomalies with a 3-inch bucket auger. Additionally, a 1 × 1 m unit excavated over a portion of Structure 1 confirmed the presence of postholes. In 2008, Pit 1 was excavated along with a larger unit over the northwest corner of Structure 1 that revealed an additional four postholes (Figure 3). In 2009, a long trench (2 × 25 m) crosscutting Structure 1 exposed additional postholes of the western wall and revealed poorly defined interior features. Pit 2 was also sampled in 2009, while Pit 3 was excavated in 2013. In 2017, a team from the German Archaeological Institute completed a landscape-scale magnetic gradient survey of the entire 15 ha field surrounding the site, revealing the presence of additional anomalies that are interpreted as two timber-post structures almost identical in size and orientation to Structure 1 (Figure 1).

Figure 3. Postholes forming the southwest wall corner of Structure 1 (National Park Service photo). (Color online)

Evidence for Craft Production at the North 40 Site

The North 40 site possesses all the expected material remains to archaeologically identify craft production—“raw materials, debris, tools, and facilities associated with production” (Costin Reference Costin and Schiffer1991:19). These classes of material correlates for craft production are unequally represented, yet each is presented here in full, as there is an expected difference in the archaeological visibility for each. Similarly, this information was included in order to document the dynamic interplay between the various material remains and facilities of craft production. The site also held a suite of material remains demonstrating that Scioto Hopewell craft production was embedded in ritualized and religious contexts. Together, these facilities and materials give the most complete picture of craft production of any site recorded in the CSV.

Debris and Raw Materials

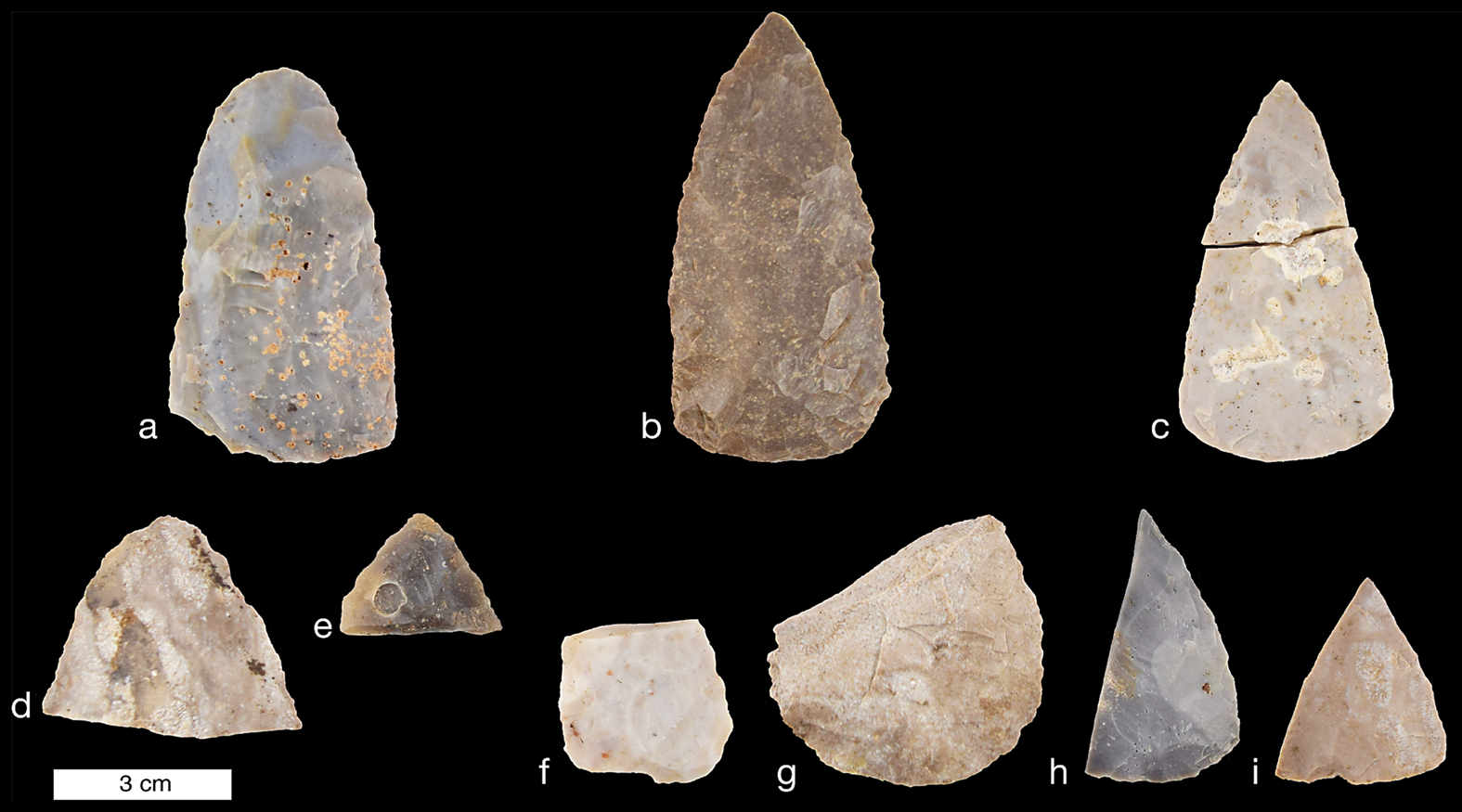

Evidence of the raw materials utilized in craft production is represented mainly by production debris rather than unworked refuse. The majority of this debris and the strongest evidence for craft production at the North 40 site are the more than 200 unfinished bifaces and biface fragments in Pits 1 and 2. These were overwhelmingly of high-quality, nonlocal (ca. 300 km) Harrison County chert (89%; DeRegnaucourt and Georgiady Reference DeRegnaucourt and Georgiady1998; Seeman Reference Seeman1975; Yerkes Reference Yerkes2009a:8–9; Yerkes and Miller Reference Yerkes and Miller2010:7–9).Footnote 3 Pit 1 contained 22 early-stage and three late-stage bifaces and biface fragments. Pit 2 contained 180 early-stage and five late-stage bifaces and biface fragments (Figures 4 and 5 and Table 1; Yerkes Reference Yerkes2009a; Yerkes and Miller Reference Yerkes and Miller2010). Additional late-stage bifaces were discovered both in Pit 3 and beneath the plowzone within Structure 1. A technological and microwear analysis of these artifacts revealed no visible signatures of use, hafting, or bag storage. Instead, each biface was either broken or rejected in manufacture due to raw material flaws or production errors that prevented proper thinning (Yerkes Reference Yerkes2009a:6; Yerkes and Miller Reference Yerkes and Miller2010:3). Thus, these bifaces are interpreted as rejects and failures, not as a cache.

Figure 4. Late-stage bifaces (a–c) and biface fragments (d–i): (a) 42565; (b) 43745; (c) 49814; (d) 42587; (e) 43635; (f) 43956; (g) 43859; (h) 43981; (i) 42576. (Color online)

Figure 5. Early-stage bifaces and biface fragments: (a) 43970; (b) 43966; (c) 44002; (d) 43957; (e) 42546; (f) 43969; (g) 43926; (h) 42584; (i) 48928; (j) 44013; (k) 44011; (l) 43953; (m) 43952; (n) 43894; (o) 43994; (p) 43936; (q) 43961; (r) 43887; (s) 43893; (t) 43895; (u) 43927. (Color online)

Table 1. Material Remains from the North 40 Site (33RO338).

Notes: CCR = crystalline rock. Ceramic data presented as sherd count (vessel count). Categories are employed or modified from Brown [Reference Brown2012].

A large sample of debitage (n = 3,742) was also recovered from all three pits, with the majority being flakes. The debitage was more thoroughly analyzed for Pits 1 and 2 to illuminate the reduction process as it relates to the numerous bifaces discovered in those pits. The assemblages from both pits are dominated by secondary reduction flakes, and both have debitage from the entire reduction sequence, likely produced during many knapping episodes. Analysis revealed that the majority of this debitage is consistent with bifacial reduction (Yerkes Reference Yerkes2009a:7–8; Yerkes and Miller Reference Yerkes and Miller2010:6–7). This, taken with the fact that the debitage from Pits 1 and 2 is dominated by the same chert type as the recovered early- and late-stage bifaces (Harrison County), suggests that this debitage is the residual from the production of these bifaces. Moreover, the shared raw material type also supports that this material was being preferentially chosen, rather than possessing more material flaws (i.e., why there are so many rejects of this raw material and not others). The quantity of debitage along with the presence of cortex on many of the early-stage bifaces supports interpretation of the North 40 site as a primary production locale.

Given the skilled nature of Scioto Hopewell craftwork evident elsewhere, it is likely that these manufacturing failures and rejects represent only a fraction of total production. This in turn suggests that many hundreds or thousands more were finished and ultimately incorporated in the archaeological record of other locales, though there is presently insufficient evidence to suggest where. Many late-stage bifaces (often identified as “blanks,” “preforms,” or “cache blades”) were interred with individuals in mounds such as Russell Brown Mound 2 (Seeman and Soday Reference Seeman and Soday1980:88) and Martin Mound (Mortine and Randles Reference Mortine and Randles1978:14) and in the embankment at Turner (Willoughby and Hooton Reference Willoughby and Hooton1922:12–13). Notably, an adult male individual interred in the southern embankment wall at Mound City (Burial [feature] 20) was buried with 10 comparable late-stage bifaces (Figure 6; Brown Reference Brown2012:186–188; Jeske and Brown Reference Jeske, Brown and Brown2012:255–256). Early-stage bifaces have also been recovered in mounds, often in large bundles such as the collection of more than 8,000 bifaces interred in Mound 2 of Hopewell Mound Group (Moorehead Reference Moorehead1922:95–96; Squier and Davis Reference Squier and Davis1848:158), almost 11,500 interred in the Baehr-Gust Mounds 1 and 2 in Illinois (Morrow Reference Morrow1991; Walton Reference Walton1962:193–199), 10,000+ at the Crib Mound (Scheidegger Reference Scheidegger1968:145–147), and more than 3,000 at the GE Mound (Plunkett Reference Plunkett1997) in southern Indiana. In each example, these assemblages of early-stage bifaces are dominated by cherts from southern Indiana and Illinois (e.g., Harrison County, Cobden-Dongola, Holland). These comparisons, taken with the overall nature of the North 40 site, suggest that these bifaces were produced for ultimate deposition in a ceremonial or mortuary setting.

Figure 6. Late-stage bifaces from Burial 20 from the Southeast Embankment Wall at Mound City: (a) 585; (b) 582; (c) 584; (d) 550; (e) 583. (Color online)

The North 40 site produced an array of artifacts of exotic raw materials representing limited craft production debris (Figure 7). Included are one fragment of copper and 59 fragments of mica from Pit 2. The copper is a scrap of sheet copper—debris from the production of an artistic piece, rather than an awl, needle, or other tool of production (Bernardini and Carr Reference Bernardini, Carr, Carr and Case2005:631). Some of the mica pieces have cut edges indicative of craft production debris. Similarly, a total of five pieces of worked crystal quartz, including one flake, two blocky fragments, and the proximal end of a crystal quartz bladelet, were recovered from various contexts. With a hardness of 7 on the Mohs scale, crystal quartz represents a difficult, if wondrous craft material, but also a crafting tool of great utility.

Figure 7. Sample of exotic raw materials recovered from North 40 site: (a) quartz crystal bladelet fragment (49808); (b) quartz crystal flake (42547); (c) quartz crystal blocky fragment (43643); (d) copper fragment (44005); (e) obsidian (43664); (f–h) mica fragments (left to right: 43851, 43853, 43884). (Color online)

Though there is not an overwhelming amount of exotic material debris from the North 40 site, this actually follows expectations. Many of the raw materials used in Scioto Hopewell craft production are nonlocal, making them costly to obtain and also endowing them with power (Bernardini and Carr Reference Bernardini, Carr, Carr and Case2005:631; Bradley Reference Bradley2000:81–84; Helms Reference Helms1988, Reference Helms1993:3). Copper crafts, in particular, involve many small pieces, such that debris was reused as rivets and other parts (Spielmann Reference Spielmann and Lynott2009:183). For obsidian, on the other hand, there seem to have been norms or restrictions regarding its deposition, perhaps due to the power inherent in the material or its necessary or honorary association with an important individual in death. The overwhelming majority of obsidian debitage has been discovered within Mound 11 at Hopewell Mound Group, and, more generally, only a few pieces of obsidian have been documented outside mound contexts (Shetrone Reference Shetrone1926:39–43).

The only possible example of unaltered raw material for craft production is 14 bedstraw seeds (Galium sp.) that were recovered from Pit 3. The limited amount makes it possible that they entered the archaeological record incidentally through “seed rain” or a host of other mundane uses known for the plant itself (Leone Reference Leone2013:12). Yet it is possible that they were brought in as a dyeing agent (Armitage and Jakes Reference Armitage and Jakes2016; Jakes and Ericksen Reference Jakes and Ericksen2001).

Tools

Lamellar blades were the most numerous tool recovered and perhaps the primary tool used at the North 40 site. This core-and-blade technology constitutes an interregional horizon marker for Hopewellian engagement across the midcontinent, with great chronological and culture-historical significance (Greber et al. Reference Greber, Davis and DuFresne1981; Miller Reference Miller2018; Odell Reference Odell1994; Pi-Sunyer Reference Pi-Sunyer and Prufer1965; Yerkes Reference Yerkes1994). Pits 2 and 3 contained 43 lamellar blades (nine whole and 34 fragmented; Figure 8). A microwear analysis on the 22 bladelets or fragments from Pit 2 shows that nine (40%) had been used for four different tasks, including cutting meat or fresh hide (n = 5), graving stone (or possibly cutting mica; n = 1), scraping wood (n = 2), and sawing bone or antler (n = 1; Yerkes and Miller Reference Yerkes and Miller2010:10). Seven bladelets from the plowzone immediately above this pit—three with use-wear (two for stone and one for meat/hide)—speak further to the multifunctional utility of these tools (Yerkes and Miller Reference Yerkes and Miller2010:10). These results are comparable to those of other microwear studies of bladelets at other sites (Miller Reference Miller2014; Yerkes Reference Yerkes2009b; see Yerkes and Miller Reference Yerkes and Miller2010:Table 6) and are nearly identical to those from the Fort Ancient site. In each case, these tools are interpreted as having been used in diverse tasks associated with craft production (Miller Reference Miller2014, Reference Miller2015), and in this case, they represent the production of various crafts of multiple media. Interestingly, the raw material patterns for bladelets stand in stark contrast to the many bifaces, being dominated by Flint Ridge (62%) rather than Harrison County (6%; Yerkes and Miller Reference Yerkes and Miller2010:9–10).

Figure 8. Sample of bladelets from the North 40 site: (a) 43864; (b) 49816; (c) 49721; (d) 49802; (e) 43650; (f) 49820; (g) 43630. (Color online)

A few other tools were recovered from Pits 2 and 3. Three hafted bifaces (one Lowe Cluster [Justice Reference Justice1987:212–213] and two unidentifiable) were discovered in Pit 2, while three hafted bifaces (two Lowe Cluster and one unidentifiable) and two fragments were found in Pit 3. From Pit 2, only the Lowe Cluster point showed any use-wear, with microwear consistent with cutting meat or fresh hide (Yerkes and Miller Reference Yerkes and Miller2010:12). Similarly, two utilized flakes recovered from Pit 2 possessed use-wear, one having been used on hide and bone or antler and the other for scraping bone or antler. Another utilized flake of obsidian was recovered from Pit 2 with a retouched edge that appears to have been used extensively (Figure 7e). Pit 3 contained various other lithic tools, including one unifacial tool, one graver, three utilized flakes, and one amorphous core. Additionally, five fragments of worked bone, likely of two small tools used for perforation, were recovered (Coughlin Reference Coughlin2019:4). The variety of mostly lithic tools along with the diverse uses identified through microwear analysis indicate that multiple craft production processes took place at the North 40 site.

Facilities

The facilities known from the North 40 site consist of at least three large timber-post structures and two perpendicular, linear arrangements of pits clustered in a small 1.75 ha area within the 15 ha survey area. These facilities contrast markedly in size, form, and spatial organization when compared with the best-documented domestic habitations in the CSV. No midden deposits or cooking features have been identified here, as would be expected for a domestic dwelling. The three tested pits (ranging in diameter from 2 to 4 m and in depth from 0.83 to 1 m) were filled with refuse indicative of craft production and ceremonial gatherings and showed no signs of in situ burning, hot rock cookery, or other activities to suggest domestic uses before infilling. Structure 1, the only structure sampled in excavation, is a building of remarkable size, with walls approximately 16 and 18 m in length and with an interior area of 288 m2. Structure 1 is a substantial architectural construction, with posts averaging 27.50 cm in diameter and 86.75 cm in depth. As noted by Bruce Smith, “A general dichotomy of scale exists between Hopewellian habitation structures and those of the corporate-ceremonial sphere, with most of the known habitation structures appearing to have been occupied by 5 to 13 individuals” (Reference Smith1992:213), with a floor area less than 85 m2. Structure 1 far exceeds this threshold, being far larger than known Middle Woodland domestic structures in the CSV (Pacheco et al. Reference Pacheco, Burks and Wymer2009a, Reference Pacheco, Burks and Wymer2009b).

In fact, Structure 1 is one of the largest Scioto Hopewell structures yet discovered, excepting the multiroomed, corporate-ceremonial rectangular structures buried beneath the Edwin Harness Mound (33RO28; Greber Reference Greber1983:15–17), Seip-Pricer Mound (33RO40; Shetrone and Greenman Reference Shetrone and Greenman1931:363–364), and Mound 25 at Hopewell Mound Group (Shetrone Reference Shetrone1926:60). The interior area of Structure 1 is over twice that for the majority of submound charnel houses or shrine buildings documented at nearby Mound City (see Brown Reference Brown2012:57–114). The formal design of Structure 1 suggests a special purpose: the perimeter of Structure 1 approximates a square with rounded corners (a “superellipse”Footnote 4), recapitulating the form of the Mound City Group enclosure and several of the submound structures and prepared clay basins therein (Brown Reference Brown2012:40–41; Mills Reference Mills1922). Unfortunately, centuries of plowing have destroyed the floor and degraded the interior features. Wood charcoal from the postholes of this structure was almost exclusively hickory (Carya sp.; 99.3%), nearly half of which was bark, suggesting that the ends of the posts were charred prior to insertion. Hickory, thus, seems to be the dominant architectural material for Structure 1—as is also known for the structure beneath the Edwin Harness Mound (Smart and Ford Reference Smart, Ford and Greber1983:54). A single, roughly circular feature was detected in the southwest corner of the structure and was identified, though not sampled, during excavation. A gravelly fill was added near the western wall during the building's construction, perhaps for structural or drainage purposes. For these reasons, we do not know how the interior space was structured.

Pits 1, 2, and 3 are clearly associated with Structure 1 based on their proximity, planned arrangement in space, shared temporality, and artifactual similarities. Pits 2 and 3 contained craft production debris, raw materials, and tools, while Pit 1 contained only debris and raw materials. These pits are arranged in two perpendicular linear arrangements with the same azimuthal orientation as Structure 1 (±5 degrees). Artifact links include a single late-stage biface found immediately beneath the plowzone in Structure 1 that shares the same dimensions as those from the pits. This is the only other known late-stage biface from the site. Similarly, the plowzone sampled above Structure 1 (above the corner and in the trench cut across its center) contained debris (debitage, n = 161) and tools (bladelets, n = 14; utilized flakes, n = 5; other bifaces, n = 4) much the same as discovered within all three pits.

Scholars (e.g., Baby and Langlois Reference Baby, Langlois, Brose and Greber1979; Spielmann Reference Spielmann and Lynott2009:183, Reference Spielmann2013:149–150) have expected that at least some portion of Scioto Hopewell crafting occurred in workshops. The available data are not sufficient to identify Structure 1 as a special-purpose building devoted solely to craft production activities. However, the data do support the interpretation of the North 40 locale as a locus of craft production embedded in a ceremonial precinct, divorced from the domestic household sphere. The spatial clustering and alignment of the structures and pits, combined with artifact cross-ties and radiocarbon chronology, strongly suggest not only a functional association between all the identified facilities but that this spatial organization was planned. The size and formal design of the structures suggest corporate or communal rather than household-level uses. The location of the North 40 locale just 30 m north of the Mound City Group mound-and-earthwork complex strongly suggests that both should be considered together as elements within a larger ceremonial precinct. Taken together with the remains of associated ritual activity documented below, the North 40 site emerges as the best-documented materialization of the ritual mode of production (Spielmann Reference Spielmann2002) in the Scioto Hopewell world.

Remains of Associated Ritual Activity

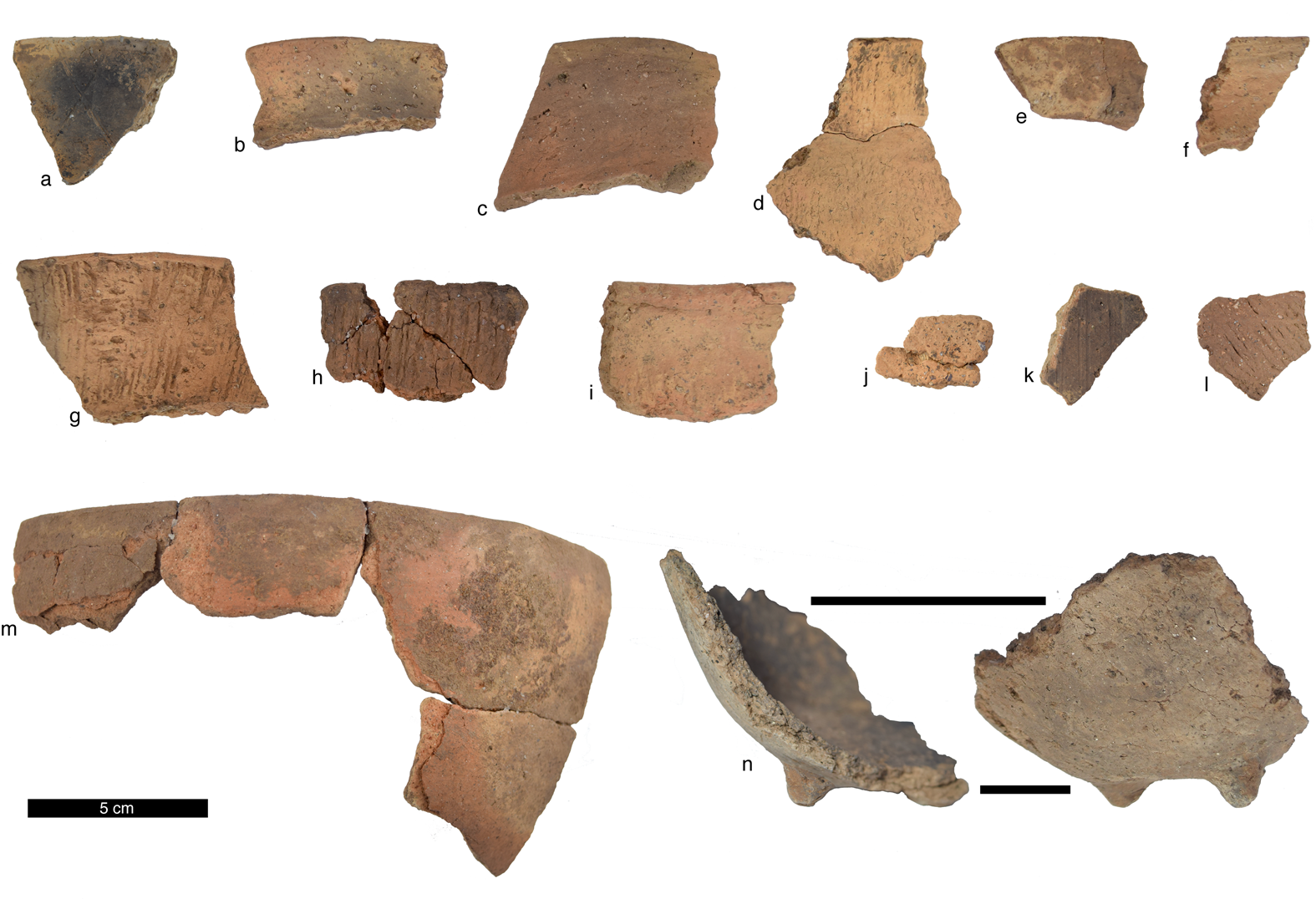

A host of evidence suggests that craft production at the North 40 site was itself ritualized and deeply embedded in Scioto Hopewell ceremonialism. Most notable is the remarkable ceramic assemblage (n = 893 sherds). We analyzed this assemblage utilizing the approach James Brown (Reference Brown2012:195–250) recently outlined for his study of the Mound City assemblage, in an effort to facilitate comparison and to avoid the main critique leveled at Olaf Prufer's (Reference Prufer1968; Prufer and McKenzie Reference Prufer, McKenzie and Prufer1965) long-standing typology: namely, that it misidentifies local and nonlocal vessels (Brown Reference Brown2012:195–196; Hawkins Reference Hawkins and Pacheco1996; Stoltman Reference Stoltman and Brown2012).

The assemblage from the North 40 site, mostly from Pits 2 and 3, is dominated by local plain and cordmarked sherds (95.7%). The 33 identified vessels (Pit 2 = 6, Pit 3 = 27) show much greater diversity, with 24 local vessels and nine “exotic” or nonlocal vessels (Figure 9). Vessels were identified mostly by unique rims but in some cases by sherd lots that were unequivocally unique either in their paste or in a combination of paste and surface treatment (Table 1; see also Brown Reference Brown2012:197). The vessels are primarily jars, but two bowls and perhaps one lobed jar and one cylindrical jar (similar to a vessel from Turner-1; Prufer Reference Prufer1968:Plate 30) are present and suggest specialized food presentations or perhaps the consumption of special foodstuffs (cf. Crown and Hurst Reference Crown and Hurst2009). At least one vessel has carbonized residue fixed to its interior, adding support for the utilization of some of these vessels in food preparation. A few vessels have crosshatched rims or highly polished surfaces, and one vessel has tetrapodal supports, further suggesting specialized consumption and display.

Figure 9. Ceramic assemblage from the North 40 site (Pit 2: f, i–j; Pit 3: a–e, g–h, k–n): (a) vessel 1 (49756); (b) vessel 2 (49832); (c) vessel 3 (49832); (d) vessel 4 (49845, 49833); (e) vessel 8 (49728); (f) vessel 2 (43755); (g) vessel 11 (49831); (h) vessel 12 (49831); (i) vessel 1 (43627); (j) vessel 5 (43609); (k) vessel 25 (49843); (l) vessel 20 (49741); (m) vessel 13 (49727, 44703, 49355); (n) vessel 23 (49807). (Color online)

The North 40 ceramic assemblage is similar to the assemblage from Mound City (Brown Reference Brown2012:246) in being primarily a local assemblage with a minority of exotic vessels of likely Southeastern derivation. The nine nonlocal vessels were from Pit 3, with eight falling into Brown's (Reference Brown2012:234) class of “Crushed Sand Tempered, Exotic Pastes” with smoothed, cordmarked, and brushed finishes.Footnote 5 Vessels of this paste are known from Mound City, and petrographic analysis suggests that they derived from the Blue Ridge region of the Appalachian Mountains (Stoltman Reference Stoltman and Brown2012:405). The presence of nonlocal ceramics is unsurprising at this location given the known interregional circulation of ceramics (e.g., Ruby and Shriner Reference Ruby, Shriner, Carr and Case2005), but this stands in stark contrast to assemblages from Scioto Hopewell domestic sites (Prufer and McKenzie Reference Prufer, McKenzie and Prufer1965). It is striking that these nonlocal ceramics seem to occur as only a few isolated sherds. The sherds seem to have been deliberately deposited, as Pit 3 demonstrated better-than-usual preservation (e.g., presence of many freshwater mussel shells and faunal materials) and does not seem to have accumulated slowly as a midden fill. That these nonlocal vessels, excepting the one bowl (vessel 13), were represented by only a few sherds is reminiscent of Feature 20 at the Duck's Nest sector of Pinson Mounds. There, sherds from 48 vessels of both local and nonlocal styles and origins were discovered in close proximity, with strong evidence that only portions of vessels were being deposited (Mainfort Reference Mainfort2013:156–170). Mainfort interprets this assemblage as the product of performance “invoking and expressing a shared sense of friendship, certain shared beliefs, and common purpose” (Reference Mainfort2013:172). We tentatively interpret the exotic sherds from Pit 3 as being akin to Feature 20 of the Duck's Nest sector of Pinson Mounds, where these exotic sherds from Pit 3 represent the materialization of a relationship between multiple communities taking part in performative ritual activities.

A ceramic smoking pipe bowl was also discovered in Pit 3 (Figure 10). Only a very few examples of ceramic pipes are known from Ohio Hopewell sites,Footnote 6 though about two dozen are known from Hopewell sites in Illinois and elsewhere. The bowl has a prominent rim and expanding medial portion, similar to a clay flat-platform-style pipe from Quitman County, Mississippi (Johnson Reference Johnson1968). Four similar examples executed in stone are known from the Illinois River Valley and are believed to date to the late Middle Woodland (cal. AD 250–400; Ken Farnsworth, personal communication 2014), consistent with the 14C assay from Pit 3 (Figure 2).

Figure 10. Ceramic pipe bowl fragment (49867): (left) profile view; (right) superior view. (Color online)

A host of food remains were also discovered from the North 40 site. Unusually high densities of cultigens along with contextual associations with smoking paraphernalia and imported vessels led Leone (Reference Leone2014) to suggest that these are the remains of feasting. While Pit 2 had only three EAC seeds present, Pit 3 produced some of the densest concentrations of cultivated seed remains seen in any contemporaneous midcontinental context. Maygrass (Phalaris caroliniana; 18.48 n/L), chenopods (Chenopodium berlandieri; 15.53 n/L), and knotweed (Polygonum erectum; 8.27 n/L) are especially well represented, with squash and gourd (Cucurbita pepo and Lagenaria sicerara), little barley (Hordeum pusillum), and sunflower (Helianthus annuus) also present (Table 1; Leone Reference Leone2008, Reference Leone2009, Reference Leone2013:8–11). Only Pit 3 had well-preserved faunal remains, dominated by white-tail deer (Odocoileus virginianus), with the majority being forelimb elements (nearly 90% being from the left side) and over half being ulnae (minimum number of individuals = 5; Coughlin Reference Coughlin2019). The specificity of this assemblage, likely representing a desire for a specific “cut” of venison, along with the fact that all ulnae were from deer younger than 20 months, suggests that these are the remains of feasting (Coughlin Reference Coughlin2019:5; Coughlin and Everhart Reference Coughlin and Everhart2019). If the comestible remains represent an event, it likely occurred in either the fall or winter, as evidenced by the floral and faunal assemblages, respectively (Leone Reference Leone2013:14). This robust array of comestible remains, together with the specialized nonlocal vessels and smoking pipe, perhaps represents the residue of feasting among individuals drawn from diverse social groups, possibly of interregional scope.

The Organization of Scioto Hopewell Craft Production

The North 40 site has all the hallmarks of a craft production site embedded in a ceremonial precinct, with facilities consisting of three outsized structures and a series of pits containing raw materials, crafting debris, and tools (Costin Reference Costin and Schiffer1991:19). The density and diversity of the floral remains (most notably the EAC seeds), the specificity of the faunal assemblage, the presence of vessels of unusual form and decoration (including nine that are nonlocal), and a smoking pipe suggest that craft production was a spiritually powerful activity. These materials were likely associated with what Seeman terms “preparatory elements of ritual,” including feasting, smoking strong tobacco, and drinking “black drink” (Reference Seeman and Townsend2004:68). This finding is in keeping with recent research on the experiential meaning of earthworks (Bernardini Reference Bernardini2004), in that it emphasizes that the processes and practices of creation for both the landscapes and objects of Scioto Hopewell ceremonialism were themselves religiously powerful.

Variation in the organization of craft production within small-scale societies results from the “scale of demand, the nature of use, the degree to which the materialization of ideology is controlled (DeMarrais et al. Reference DeMarrais, Castillo and Earle1996) and the contexts in which populations . . . aggregate” (Spielmann Reference Spielmann2002:201). The North 40 site, with its outsized and formal architecture, abundant crafting debris and tools, and associations with smoking and fancy and imported serving vessels, demonstrates that Scioto craft production was at least predominantly located away from the domestic sphere, an anomaly within small-scale societies. The Scioto Hopewell case follows Spielmann's (Reference Spielmann2002:202) prediction that in societies where ceremonial centers are the locus for ritual aggregation, they may also host craft production. The North 40 site is immediately outside the Mound City enclosure, which was certainly a center for aggregation, and was likely part of an integrated ritual landscape. This organization of craft production accommodates the technical and esoteric knowledge required for production, the power inherent within many of these materials, the structuring of ceremonies around places of ritual aggregation, and, to a lesser extent, the logistics involved in acquiring the exotic raw materials for production and the demand for thousands of sacred and symbolically charged objects. Yet this organization almost certainly contained some variability, with some raw materials likely having been crafted at a household level. Mica debris, for example, has been found at a number of domestic sites within the CSV and beyond (Blosser Reference Blosser and Pacheco1996:58–59; Pacheco et al. Reference Pacheco, Burks and Wymer2009a, Reference Pacheco, Burks and Wymer2009b; Prufer Reference Prufer and Prufer1965:98), perhaps suggesting that it was crafted within households because it is the simplest material to transform (Spielmann Reference Spielmann and Lynott2009:184).

The craft production remains and facilities from the North 40 site also offer an opportunity to further interpretations of other sites within the CSV. The Datum H (Pacheco et al. Reference Pacheco, Burks and Wymer2012) and Riverbank sites (33RO1059; Bauermeister Reference Bauermeister2010) at Hopewell Mound Group, Structure 1 at Hopeton (Lynott Reference Lynott2014:199–122), and the seven structures inside the Seip enclosure (Baby and Langlois Reference Baby, Langlois, Brose and Greber1979; Greber, ed. Reference Greber2009) all bear some resemblance to the North 40 site, and further research may reveal a component of craft production at each. The case of the structures within the Seip enclosure is especially instructive, given the long-held notion of these structures as craft production locales (Baby and Langlois Reference Baby, Langlois, Brose and Greber1979). The recent reinterpretation of these structures cited an inability to link crafting debris with them and ultimately deemed the area instead as a “place of rituals” (Greber Reference Greber2009b:171). While the taphonomic considerations are valid, it is important to note that places of ritual and craft workshops are not mutually exclusive spaces. In fact, the North 40 site demonstrates that Scioto Hopewell craft production locales were places of ritual. As such, a reanalysis of some of the aforementioned sites may conclude that they may well have been craft production sites.

Evidence from the North 40 site demonstrates that multiple media were being crafted at the same craft production locale. This includes at least mica, chert, and copper. Given that crafting style is media-specific (Seeman Reference Seeman and Townsend2004:64), it is somewhat surprising that production locales were not also specific to raw material. Though it may be the case at Mound City, there is not yet enough data to suggest that craft production was practiced at, and specifically for, each earthwork. The crafting debris recovered from the North 40 site is in keeping with the emerging consensus that raw materials were obtained through direct acquisition (e.g., Bernardini and Carr Reference Bernardini, Carr, Carr and Case2005:632–634; Carr Reference Carr, Carr and Troy Case2005b:579–586; Seeman et al. Reference Seeman, Nolan and Hill2019:1098; Spence and Fryer Reference Spence, Fryer, Carr and Case2005:731; Spielmann Reference Spielmann and Lynott2009:180–181) and locally crafted (Braun Reference Braun, Renfrew and Cherry1986), although this was likely not the case everywhere for all materials. Recent research at the Garden Creek site in the Appalachian Summit has demonstrated that communities near the source of mica were unequivocally engaged in ritualized crafting (Wright and Loveland Reference Wright and Loveland2015). Four Copena-style steatite “Great Pipes” have long been known from the Seip-Pricer Mound (Shetrone and Greenman Reference Shetrone and Greenman1931:416–424), and recent petrographic analysis has documented ceramics from the same mound that are both stylistically and compositionally nonlocal, likely originating from various regions in the Southeast (Stoltman Reference Stoltman2015:161–186). These examples, along with others, suggest that at least some completed objects were transported back to the CSV. Thus, the organization of craft production was variable, likely differing by raw materials, and was also perhaps time-transgressive.

While many aspects of Scioto Hopewell ceremonialism affected various social structures and daily life, the separation of craft production from the household has among the most important implications. While the temporality of crafting, and to what degree artisans were specialists or not, is yet unknown, their activities had to be economically offset. In this case, this is true to a far greater extent because craft production was removed from the domestic sphere. At some level, the subsistence economy had to be restructured. On one hand, it had to be intensified to support diverted labor (Spielmann Reference Spielmann2002), and, on the other, patterns of distribution had to be altered to provide gathered comestibles to the North 40 site. This diverted labor goes beyond just the artisans themselves and likely includes different personnel responsible for clearing the old-growth forest in this area and constructing the massive architectural structures. Evidence also suggests that artisans were perhaps feasting at the site as part of the spiritually charged crafting processes, making this even more economically demanding.

The organization of craft production outside the domestic sphere also added to the overall complexity of settlement systems, adding a node to the network that at least a small portion of the population had to travel to, occupy, and maintain. It is yet unseen how Scioto Hopewell leaders gained and wielded power to schedule, plan, and organize the complex ceremonialism, but the separation of craft production from other arenas of daily life certainly added to this complexity. Similarly, artisans must have held unique positions within society, adding complexity to the overall sociopolitical organization (Brandt Reference Brandt and Blackburn1977; Helms Reference Helms1993). Specifically, this increased the number of social roles and diversified social identities. It also forged a number of new relationship types divorced from kin relations, as is typical in small-scale societies (Spielmann Reference Spielmann2002), such as master and apprentice, producer and supplicant, and host and visitor.

Conclusion

Scioto Hopewell rituals centered around the construction of massive earthen monuments and the production of a tremendous quantity of ornate crafts. The organization of craft production beyond the household at the North 40 site is an unusual example among small-scale societies, thus adding to the known complexity of ritual economies of small-scale societies (see Spielmann Reference Spielmann2002). Artists possessing esoteric knowledge crafted intricately designed objects at this locale using multiple powerful materials (DeBoer Reference DeBoer2004:99; Seeman et al. Reference Seeman, Nolan and Hill2019; Spielmann Reference Spielmann2002:198, Reference Spielmann and Lynott2009:179) on a grand scale. Moreover, evidence from the site shows that craft production was not simply a prerequisite to Hopewellian ceremonialism but likely integral to a ritual complex involving feasting and smoking among probably a host of other ritual practices. The implications of craft production organized and operationalized in these fashions highlight the importance of understanding the social dynamics of small-scale societies through the framework of ritual economy.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Park Service. In particular, Jennifer Pederson-Weinberg and Kathleen Brady began this research at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park. Thanks also go to the many crew members who carried out the fieldwork at the North 40 site. Magnetic gradient data resulted from a collaboration between the National Park Service, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut (special thanks to Friedrich Lüth and Rainer Komp), SENSYS, Bournemouth University, and Ohio Valley Archaeology Inc. John Klausmeyer offered assistance with the creation of the figures. We thank Jennifer Larios for translating the abstract into Spanish. This article was dramatically improved by the editorial support of Lynn Gamble and by the comments offered by Alice Wright, Mark Seeman, and two anonymous reviewers. We also appreciate the helpful feedback provided by Hannah Hoover, Martin Menz, and Brian Stewart on various drafts of this article.

Data Availability Statement

All analyzed materials, analytical tables, and specialist reports are housed at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Chillicothe, Ohio.