After the first peak of the COVID pandemic (May 2020), the United Kingdom (UK) government hosted a virtual meeting of the ‘Responsible Business Roundtable,’ involving policy makers, business, academics and civil society actors. Included in the agenda was discussion around a ‘new social contract’ and a ‘new modern corporatism’ that could improve the stability of social cooperation with business, after a period of dramatically changed economic conditions and interventionism. The meeting led to the commissioning of a report, which considered the ‘rights’ that the UK government had ‘earned’ during the pandemic to reset the agenda on the economy. Footnote 1 The report included research on the ‘priorities’ that (primarily) business leaders now ‘wanted to share with the government,’ and proclaimed a new willingness on the part of business leaders ‘to support and welcome clear government actions on how businesses can contribute to “building back better.”’ Footnote 2 It sought to build upon the innovation and sense of shared purpose to improve outcomes, which businesses, governments and also members of the public were able to experience at different points in the global public health crisis.

This report is an apt starting point for this article about the corporation and ‘the social contract with business,’ where it sees in COVID, and the transformations that it catalysed in law and political economy and corporate purpose, some opportunities for rethinking the strategies for responsibilising and, also, ecologising business. Governments in Europe and the UK used innovative forms of interventionism (fiscal stimulus, business loans, rent, mortgage and employment protection schemes) to defend public interest at the peak of the crisis. Footnote 3 This creative approach disrupted an imaginary with a thought-lock on the approach of many governments to economic governance in recent decades, commonly referred to as ‘neoliberalism,’ and which has cultivated a retreat in collectivism (and government) and the encasement of social concerns in markets. Footnote 4 Many companies also connected to the public nature of the health crisis, and acted out imaginaries of stakeholder responsibility, moving resources to shield workers, creating flexible work patterns and producing vaccines and medical supplies needed urgently. Footnote 5 Notably, though, as many multinational companies exhibited more standard economic behaviour and concern for corporate welfare, invoking ‘force majeure’ in supply chain contracts, cancelling orders, imposing price deductions, and refusing to pay for goods despatched and/or in production. This had an impact on workers, as suppliers were forced to lower pay and make redundancies. Footnote 6 Such varieties and compromises in the ability of companies to act with solidarity matter, and stand out for this introduction, where they are a stark reminder that the origins of the social contract with business reaches not into the ‘sharing nature’ or ‘voluntarism’ of business - a telling reference, in the UK report, to the dominant imaginary of corporate (self) regulation over the last thirty plus years. They extend, rather, into the history of the corporation as an actor and institution in a contract with government, subject to public licence, captured as early as 1651 by Thomas Hobbes. Footnote 7

The present article draws inspiration from this second institutional scene. It looks at the potential of a social contract analysis to reframe corporate regulation and governance in an age of pressing public purposes. Footnote 8 It seeks to interrupt the controversial progress of neoliberalism as an economic but, also, governance project, which has put developing the voluntarism or autonomy of business before the relationship with government and society in many jurisdictions. The list of controversies motivating the research encompasses evidence of rising inequality and precarity, including outsized executive pay at companies and upward trends in shareholder payouts, which increased fourfold from 1992 to 2018. Footnote 9 It, also, includes an environmental crisis unabated by current rates of pollution and resource consumption, Footnote 10 and decline, inexperience and corruption at government itself, after decades of ideological estrangement and economism (which exacerbated the mismanagement of commercial relationships during the COVID emergency, in the UK). Footnote 11 The author does work, after these ruins, to reframe debate about the ‘social question’ in corporate law, sometimes referred to as the ‘problem of corporate social responsibility’ or CSR. The analysis is concerned with the impact of companies on society but, also, with matters concerning public licence (in Hobbes, ‘with Bodies politique for the ordering of trade’), and with how this licence or authority is configured at the level of constitutional government, including aspects of legal technique. Footnote 12 The author specifically introduces this notion of government and public licence as a means to address what the author perceives to be a deficit in contemporary treatment of the social question in corporate law studies. This deficit concerns the recent outgrowth of governance discussions, which absorb and contain societal issues within the walls of self-governing companies and economic rationality. Social contract matters are buried, or confused, in this literature with the question of ‘in whose interest is the company run’, and with regulatory developments concerning the quasi-public (but, also, quasi-private) development of directors’ duties, risk management and disclosure. Footnote 13

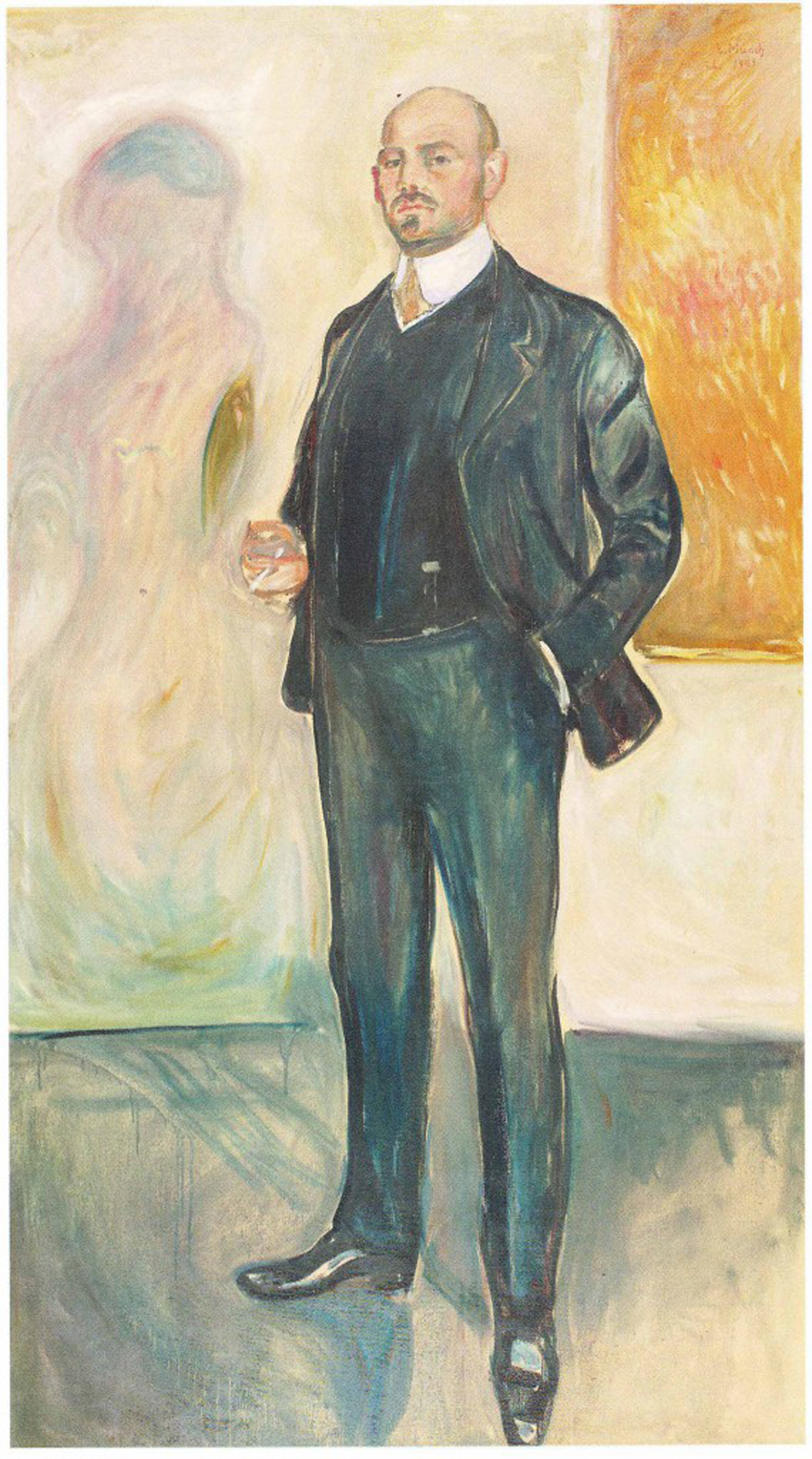

The article develops a historical approach to rethinking the corporation and the social contract with business, which is centred conceptually on the turbulence of the interwar era in Europe and America. This is the era in which the modern corporation was first implicated in social analysis (namely, in Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means’ The Modern Corporation and Private Property, published in 1932). Footnote 14 The era also stands out, to the author, as an important time for forming and testing intervention in the economic sphere, as governments were forced to ‘interact with new forces in mass society’ after the devastations of World War I. Footnote 15 A period of progressive political economy is widely considered to follow on from this interaction, and has often been studied in the corporate law studies context. This article, by contrast, drives its curiosity at slightly earlier events and more formative intellectual histories, which preceded – and in some sense contributed to bringing about – the progressive transformations of the mid 20th-century political economy (the New Deal, Keynesianism, the welfare state, industrial democracy, etc.). Specifically, it studies how the social question became embedded in company law, tracing the story from the 1930s to the present in an attempt to look for meaningful discontinuities, ie, moments where effective treatment of the social question was put at risk or went astray. This is before the author looks backwards to the 1930s and a preceding period, the end of the second industrial revolution, in an analysis that uses more eccentric historical remains to unsettle the necessity of mainstream thinking about corporate governance. This eclectic and historical analysis is centred on the creative energy of an ensemble of writers, thinkers and, also, a painter, connected through a shared interest in the ‘consciousness’ of the late 19th-nineteenth century and industrial age. Footnote 16 The aim is to unearth and to explore sidelined elements of economic and social history (ideas, nuances, circumstances, lineages), which might have meant more than those that went forward. A means for rethinking the company and social contract is, sought in such ‘salvaged histories’ or corporate law remains.

The article is divided into two parts (Part 1 and 2) and a summary analysis (Part 3). Part 1, A, defies everything just said about history and starts with the case of mass redundancies at major UK ferry operator, P&O, in early 2022. Part 1 uses this recent incident to place the so-called neoliberal company fully in the present, but, also, to illuminate the article’s main themes and concerns. Scandals at the company are described, before being juxtaposed with more extended comments about how private governance techniques underlie the P&O regulatory crisis and outcome. The mind of the reader is turned in this context (and from the start) to how law and governance portend to resolve social conflicts at companies and to applied aspects of the current social contract with business (which the article then goes on to study).

Part 1, B, then continues by tracing the development of the social question in company law from the 1930s to the present. It starts with Berle and Means’ classic text, The Modern Corporation and Private Property, published on the eve of the New Deal, in America, and eager to broker a new partnership between government and large industrial corporations. A new capacity for self-governance and ‘enlightened administration’ is foretold, in the narrative, in response to the rising autonomy of companies and their ‘quasi-public’ governing qualities, after the ‘separation of ownership and control.’ The book and statement have been much pored over since, for their capacity to redefine the social contract as a question about whether companies might engage with society directly via their governance processes, ie, by widening the concerns or the ‘interests of the company’ to include the stakes for communities and participants. Part 1 observes how this theory about stakeholder purposes at the company collided with a ‘progressive’ period of governance in the 1950s and 1960s, as government interventionism also worked to clarify social obligations that companies could and should attend. However, an aggressive turn against state interventionism and industrial democracy in the late 1970s and 1980s, the beginnings of the so-called ‘neoliberal era,’ would soon change the terms of corporate socialisation. Shareholder demands strengthened their hold over the governance of companies, and the role of the state was to shift from intervention (or ownership) to promoting the market coordination of needs and outcomes, wherever possible. Progressive regulatory theorists, working in capitalist economies, quickly had to rethink the best available means to maintain sight and application of the social question in this context. The biggest dedication of the research in the rest of Part 1 (C-D) is to describe and evaluate the terms of this rethink.

This part (C-D) critically studies the development of ‘new’ or ‘regulatory’ governance, in this historical context, as a regulatory technique that responded to (grew alongside) political-economic developments of the 1980s. Notably, it shows how legal scholars working on these ideas came to share in the era’s pessimism about law and government, identifying problems with the effectiveness of traditional (regulatory) techniques. Pressed about the social question in the context of globalisation and rising corporate power, regulatory theorists sought to repurpose the company as an alternative site for progressing regulatory agendas abandoned by the 1980s governments. They identified new spaces for creative adaptation within corporate autonomy and governance that could be ‘responsive’ to public conflicts. New procedural forms of regulation were instituted as a means to involve companies and the wider public, which went by the name of ‘functional equivalents’ (to traditional legal instruments). However, significant problems are identified, by the author, concerning the proliferation of these equivalents, which maintain the neoliberal project by confining the law to process and deputising legal force and function to a mix of price, competition and (increasingly) scandal (‘a circumstance or action that offends propriety or established moral conceptions or disgraces those associated with it’). Footnote 17 A deeper analysis seeks to explore how the social contract between companies and government is reconfigured in this context. The author remarks on the tendency of regulatory governance to supplant individualised solutions, created by companies for gain, for public authority and the damage that this does to law, justice and also comprehensive understanding of corporate economies and their impactfulness, insofar as government is (ideologically) resolved to be indifferent to outcomes, or over-invests in companies and markets as the means to collective creation.

Part 2 of the article develops a different perspective in response to this critique, standing at the turbulent hinge of the 1930s, again, but this time looking the other way. A lineage is drawn from Part 1 to Walter Rathenau, German industrialist, Weimar politician and scholar, writing on corporations in Germany (1917–1922). Part 2, A, explores some of the circumstances and associations of Rathenau, as a means to learn more about the commitments that he held and the corporate law concepts that he identified. Footnote 18 It finds that Rathenau’s understanding of the company placed a lot of emphasis on the social contract and regulatory principles, even as he proclaimed advances in large-scale corporate administration and enlightenment. His theories did not contemplate a significant expansion of corporate self-government, but were closer in imagination to peers like John Maynard Keynes, also interested in the corporation and collectivism (and a government of ‘intelligent design’). Footnote 19 Part 2, B, seeks to deepen understanding of Rathenau’s social contract insights. It extends the timeline over which Rathenau’s interest in political economy developed to the heat and disillusion of the late 19th-century, exploring the rebellions against fatalism that informed and shaped Rathenau’s perspective. Part 2 connects a spur to creation (‘Creabimus!’) and technical innovation, which Rathenau shared with the late 19th- century industrialists but also artists, to the co-evolution of companies with public government as a means to staying connected with the metaphysical dimensions of economic regulation (higher questions) and developing law’s ‘equalising’ powers. The author also identifies key concepts to help with the reconstruction of the social contract with business from the analysis, including a reserve power to ‘recognise what is amiss’ (Rathenau), a regulatory ‘Agenda’ for government in the realm of the ‘technically social’ (from Keynes), and the potential for obligations and ‘economic sacrifice’ to be developed in situations of extensive (or emboldened) corporate abuse (Berle).

The final part of the article (Part 3) is more summative. It seeks to mobilise a more constructive instinct for corporate regulation using the social contract question, and after finding a more congruent reading of the company’s relation with law and government in Part 2. Part 3 details some of the commitments and cooperation that could be required of companies under new legal and regulatory frameworks in exchange for public licence, limited liability or, in some circumstances, government and taxpayer support (as happened in the pandemic). Reforms for corporate governance are also covered (briefly), though re-framed by the histories of the social contract, contrasted in Parts 1 and 2. The proviso to ‘recognise what is amiss’ (Rathenau) collides, in this part, with a wider call for institutional experimentation, which seeks to overturn a culture of economism and to constantly improve on law’s ineffectiveness (flawed progress as an improvement on economic fatalism). A new modus of ‘regulating dangerously’ is identified in the last paragraphs, which underscores the importance of creative experimentation in instituting the social question and particularly for long neglected legacies of commercially beneficial destruction. The article makes institutional transformation about shifting onto a different historical axis, whereby we might re-learn collectivist ambitions around corporate organisations that co-evolve with law and government, enlivened by the public interest (and not as their functional equivalent). This regulatory modus the article titles ‘Creabimus!’

1. The neoliberal corporation and social contract

A. On corporate governance and scandal at P&O

In March 2022, P&O Ferries in the UK, part of the P&O shipping group originally chartered by a Londoner and a Shetlander in 1840, was scandalised in newspaper headlines across the country. The company had sacked all of its UK crews, comprising 786 employees. Footnote 20 Without notice, the company (reportedly) used MS Teams, phone and text messages to communicate a message that employment for the unionised crew members was terminated ‘with immediate effect due to redundancy,’ a communication tactic that added to the scale of negative publicity, due to its apparent lack of respect for the dignity of employees. Footnote 21 In the days after the mass redundancies, vital public transport services provided by P&O from England to Europe, Ireland and Scotland, were suspended, whilst the company located new crews and managed the scandal. Replacement staff were to be contracted from an agency supplier at lower wages (namely, non-UK based contractors to avoid domestic minimum wage and union laws), according to the firm’s own publicised strategies. Such a substitution of labour was proposed to be in the service of flexibility and cost-savings, or a ‘last resort’ response to losses suffered by the firm due to COVID-19 and deficits in the pension fund. Footnote 22

Significant public outrage followed the mass terminations, or (as UK labour lawyer Keith Ewing aptly names it) ‘fire and replace’ incident, much of which was focused on the company’s callous approach to the rule of law. Footnote 23 Questions were raised by lawyers, trade unionists and politicians about the company’s failure to comply with UK and international employment standards. Footnote 24 Specifically, the company had neglected to inform and consult workers’ representatives about their decision to dismiss workers for reasons of redundancy, or to notify the Secretary of State or relevant authority in the flag state as required by the Trade Union and Labour Relations (Consolidation) Act 1992. Footnote 25 Wider questions arose about the liability of the company for unfair dismissal, breach of directors’ fiduciary duties, the prospect of directors’ disqualifications and shareholder actions for damages, Footnote 26 the safety implications of sailing with inexperienced crew, Footnote 27 the (uncertain) entitlement of agency workers to the UK National Minimum Wage (NMW), Footnote 28 and breaches of international human rights law codes and standards by the company, but, also, the UK government for failure to ‘prevent, investigate, punish and redress’ abuses of rights taking place within its jurisdiction and territories. Footnote 29

By January 2023 (the time of writing), P&O Ferries was reported to be waiting to take delivery of two new cross-channel ferries, ‘its largest to date’, having largely weathered the scandal. Footnote 30 Charges were not pursued by the UK government (after some months of consideration). Footnote 31 Despite this quieting of the scandal, the present article continues to take interest in the events at P&O, where the actions and reflexivity of the company at the height of the crisis speak to essential features of the neoliberal corporation and social contract, and their (troubling) continuity into the present. The events severed, for instance, the public spirit and collaboration, which the country tried to experience during COVID. Renewed optimism about the need for systemic change in the economy, including imaginative talk about the ‘future of work’ and respect for essential workers, was stymied and overshadowed by the cynically planned and executed redundancies at P&O. The clear resumption of economic priorities, as is involved in ‘fire and replace’, aligned less with hopes for ‘a new social contract’ and more with a recent history of the neoliberal corporation that aims at reducing labour and production costs, whilst increasing the portion of private gains for shareholders. Footnote 32 Private property dimensions to this company were also able to protect the business from any broader demand for public accountability or interventionism. What emerged, instead, was strategic development of the facilities of corporate autonomy in the private sphere, including space to create the cost-cutting scheme with lawyers skilled in ‘creative’ compliance, whilst relying on the facilities of corporate separate legal personality to justify (ie, rationalise) cuts within an otherwise profitable corporate group. Footnote 33

Members of the company board were questioned by the Government select committee in the days after the sackings were announced. Predictably but, also, meaningfully, P&O executives defended the actions taken in economic and competitive terms. Months of consultation with workers, although a legal requirement, would have ‘undermined the business, caused disruption, which would have led to customers leaving for competitors,’ said CEO Peter Hebblethwaite. Footnote 34 Avoidance of consultation had, in fact, ‘safeguarded the long-term future of the company and the livelihoods of 2,200 employees.’ Footnote 35 Employment law requirements, in such a view, were strategically treated by the management as a ‘business cost’ and ‘efficiently breached.’ Or (to translate the statement further) fiduciary duties, in the CEO’s interpretation of UK company law obligations to promote the ‘success of the company’ for the benefits of the members could, in challenging circumstances, perhaps even require some form of law-breaking to protect the company’s share price and long term viability. Similar thinking was applied by P&O Executives when explaining the company’s approach to redundancy monies for workers, which were paid (up front) but without compliance with the statutory consultation process. Company legal representatives assessed the monies paid as being ‘fair’ due to their being comparable to the level of statutory compensation that would have been due, if the legal requirements were followed. In this context, the board claims to have had ‘regard’ for the applicable legal requirements, just without offering due process at law. Footnote 36

Such deep commodification of labour law is not new or unheard of (of course). Since at least the 1990s, it has been common to observe calculative reflexivities, like this, about law, regulation and common standards among business actors, tasked with maximising profit and dividends for investors on the global stage. A ‘race to the bottom,’ which mixes the dynamics of markets and competition and skills of regulatory arbitrage (ie, whereby firms capitalise on loopholes in regulatory systems in order to circumvent unfavourable regulations) has been widely problematised by anti-corporate activists, as chief among the exports of economic globalisation. Footnote 37 Each is now widely rooted in the global corporate and financial sphere.

The P&O Ferries’ example is still distinct and interesting despite not being new, though, and not just because it carries to the UK what has been exported elsewhere, namely a market-bound mentality ready to act among (deplete) rights and duties for corporate ‘success’ (although it does this too). The events further cause shock because they force an awkward confrontation with a highly developed regulatory imagination, which for the last thirty years has encouraged companies to self-determine or ‘regard’ risks to themselves, and others, as a proxy for respecting law in the economic sphere. Such an extension of corporate rule, delivered at a ‘best efforts’ standard and on a competitive basis, has been widely presented as among the benefits of corporate social responsibility (CSR), for instance. Footnote 38 Justification for this approach is extended where the rule of law is weak and companies offer an opportunity to use their organisational habits and reflexive constitution to improve standards internationally, often where governments are unwilling or unable to legislate. Footnote 39 Relatable habits arise at P&O, where the CEO defends the company’s breaches in terms of the extra ‘insight’ or pragmatism that he and his board can bring to the table (not consulting when the company already knows the outcome, for instance), and compares this by implication to the inefficiencies of UK state and judicial forums (when agreeing compensation without a court), which are being disinvested after the same imaginaries. Footnote 40 Volatility is evident as the bet (of conscience or good judgement) does not pay off (in this case); rather, without effective action (ie, enforcement), the risk of volatility passes down the line to other workers. Footnote 41

Significantly, many of the scholarly proposals for improving corporate self-governance and reflexivity in fora like CSR do still imagine the company in a social contract, and law and government as backing the market-led organisation of interests (and so demur conceptually from a moment of self-constitutionalisation). Footnote 42 However, the deferential approach of the Conservative Government, as well as the recent UK report about governments ‘sharing’ in company purposes (in the introduction), allow us to glimpse an increasingly disembedded (as Karl Polanyi might have had it) approach to the rule and authority of companies, festering in the move to give companies law-creating powers. Footnote 43 The P&O Ferries case, as such, says something about the social contract dimensions to the systems of corporate government, developed and exported within advanced capitalist systems under conditions of neoliberalism. A social contract conflict erupts, at P&O, where one reading puts democratic law and government as the source of the company’s licence and legitimacy, which then meets another that makes companies’ economic functions (creating wealth, innovation, jobs) self-standing or prior. The latter is justified at P&O as the best (or only?) means for society to pursue collective creation, even where this involves standing down legal rights and facilities, if not the rule of law itself.

Such examples and prospects give the author occasion to find out more about the corporation and social contract. There is more to understand about how this economic and functional priority historically arises and reconfigures the social contract with business, including law’s normative discovery and development, public supervision and enforcement, the realisation of common objectives, democratic input and deliberation, etc. Such things interest the author as applied aspects of the social contract with business and the contemporary institution or delivery of corporate regulation, formed in its midst.

B. How economic rationalities came to dominate the governance of ‘wider interests’

It is common for business law scholars to use the 1930s as a point of departure for studying modern corporate social institutions, including the relationship between the company and society, or CSR. Footnote 44 This entry point to the modern company (the 1930s) reflects the era’s ability to mix turbulence and transformation, as capitalist economies navigated the fall-out from World War I and the depression that developed after the 1929 stock market crash in America. Footnote 45 The era gives scholarly carriage, too, to The Modern Corporation and Private Property (1932), by Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means, a seminal text for theorising the ‘modern’ corporation. The book transformed thinking about business by relating a new concentration in industrial power at companies to the ‘social question’ and to new features of business and investment, most notably ‘the separation of ownership and control’. Footnote 46 Along with the involvement of Berle in the debates with Merrick Dodd in 1931 and 1932 about stakeholder versus shareholder governance, the book introduced new ways of interrogating the company’s nature and purpose and relating corporate governance to societal issues. Footnote 47 Berle, a lawyer and academic, was also a speech writer for Theodor Roosevelt at the time of the book’s writing (ie, on the eve of Roosevelt’s election and the New Deal), a relationship that hints at the wider engagements of the book and authors in shaping the social contract with business during the interwar era. Footnote 48

Berle and Means were, in many respects, writing a book for corporate lawyers about shifts in the balance of economic policy and decision-making, which were created by the emergence of large enterprises and new dispersed modes of stock ownership. Footnote 49 However, they were also keenly aware of how corporate governance had to adapt, for legitimacy and in the context of war and depression, to the visible capacity of powerful firms to malign as well as benefit public interests (companies could, they said, ‘harm or benefit a multitude of individuals, affect whole districts, shift the current of trade, bring ruin to one community and prosperity to another).’ Footnote 50 For the authors, countering this societal impact and depression meant transforming corporate power and authority by subjecting it to ‘tests of public benefit’: ‘In time of depression, demands are constantly put forward that the men controlling the great economic organisms be made to accept responsibility for the well-being of those who are subject to the organisation, whether workers, investors, or consumers.’ Footnote 51 Yet, the authors were also keen for political reasons, including the necessity of maintaining the ‘confidence of business,’ not to restrict business freedoms; they wanted, rather, to reform corporate power and social authority. Footnote 52 In this context, Berle and Means used logic and social optimism to reshape important parts of the social contract with business, envisaging a partnership with government, but also a reformulation of corporate autonomy as ‘state-like’ or ‘quasi-public’. Citing the work of Walter Rathenau in Germany, they constructed a sense of companies being on the brink (after the separation of ownership and control) of gaining (earning) a new capacity to ‘govern’ in the general interest. Footnote 53

In the last pages, in a chapter titled ‘The New Concept of the Corporation’, Berle and Means used this insight to form a governance perspective on the modern enterprise (‘The institution here envisaged calls for analysis not in terms of business enterprise but in terms of social organisation’). Footnote 54 New independence within the corporate entity from shareholder claims increased, in their view, the potential for enlightened governance at companies, as management should evolve into a ‘neutral technocracy,’ capable of balancing ‘a variety of claims by various groups.’ Footnote 55 The book identifies potential changes in the character of the corporate profit stream, as related to this capacity for public governance. Profits earned could no longer be classified as purely private property; ‘Claims on it must be adjusted by some other test, other than that of property right,’ where shareholders, surrendering control, ‘surrendered the right that the corporation should be operated in their sole interest.’ Footnote 56 Berle and Means reference community claims ‘put forward with clarity and force’, which might move the company towards more responsive forms of production and action in this context. Footnote 57 They also explain their ‘temporary’ preference for maintaining shareholder loyalty, insofar as ‘a convincing system of community obligations’ was not yet (in 1932) in place (they talk about a need for obligations to be ‘worked out’ and communities generally ‘accepting such a scheme’). Footnote 58 Wider expectations that business practitioners would increasingly ‘assume the aspect of economic statesmanship’ and that corporate law might form a basis in ‘constitutional law for the new economic state’ are expressed, though somewhat ambiguously (ie, as advancing, but not necessarily being dependent on the enlarged respect for community interest). Footnote 59

Such was the force and (perhaps) ambiguity of this description of the company as expanding in the means of self-government that Berle and Means were able to prophesy their own origins moment: ‘How will this demand [for responsible power] be made effective? To answer this question would be to foresee the history of the next century.’ Footnote 60 After World War II, social and labour movements would advance further on the governance prospects elaborated by the authors and on the company’s quasi-public orientation, as the corporatist collaboration for growth and jobs was instituted. Footnote 61 By the 1960s, John Galbraith, in The New Industrial State, was able to narrate the company’s ‘socialised’ and ‘bureaucratic’ transformation. The book highlighted new forms of motivation among directors suited to advancing the public interest and the long-term success of corporate organisations engaged thus, which Galbraith termed ‘enlightened administration.’ Footnote 62 Importantly, these capacities in governance grew during a period of constancy in corporate legal frameworks (ie, no new duties were introduced for companies or directors in the law) but, also, strong public government and collectivism (social legislation, regulated finance) and collective bargaining. In the terms used by Berle and Means in 1932, this wider instrumentalism granted ‘clarity and force’ to many of the era’s normative expectations of business. Footnote 63 In support of this view, when writing for Roosevelt, Berle had earlier talked about companies sacrificing ‘this or that private advantage’ and seeking ‘general advantage.’ Such enlightenment involved not voluntarism, the writing clarifies, but a prospect that should companies ‘use its collective power contrary to public welfare, the government must be swift to enter and protect the public interest.’ Footnote 64

A different deployment of corporate autonomy and corporate socialisation, which again speaks to the ambiguities of how the modern company was theorised in the 1930s, was to emerge after the mid 1970s. Corporate law scholars talk about the sudden disappearance (‘overnight’) of the motivational ethos and collaborative underpinning of the ‘Galbraithian corporation.’ Footnote 65 A powerful rewriting of the post-war social contract was going on against the backdrop of rising social and economic conflicts – an oil crisis, inflation, and industrial and competition from manufacturing economies in the Global South. Footnote 66 Intellectuals like Milton Friedman (discussed by Bartl, this issue) and Fredriech Hayek, who had been writing against the post-war social contract and corporatism since the 1940s, waded into the turbulence, this time. The new ideas and theories sought to relate rising conflict around the economy and industrial participation to the dangers of instrumental law and government (‘the road to serfdom’), Footnote 67 and a government’s ill-adaption to the ‘knowledge’ or ‘discovery’ demands of a decentralised market society (others talked about the ‘overloaded state’). Footnote 68 Such ideological interventions proposed adaptations in the social contract, to make law and government more minimal (the enforcer of contracts and property rights). On the other hand, however, governments were also expected to extend their involvement in creating, steering and facilitating exchange and markets, as a means of advancing the core idea that social institutions, planning, and fixed structures were all ineffective, and (through the efforts at improvement that this catalysed) always on the road to becoming more repressive.

By the 1980s, elected politicians began to institute transformations in the social contract with business that expressed these new beliefs or theories, through anti-union legislation and wider policies that aimed at reducing state control over the economy (privatisation, capital liberalisation, deregulation). Footnote 69 This programme aimed at growing the role of markets, as allocative devices, and reducing ‘red tape’, the ideologically loaded tag for public regulation and standards. Footnote 70 New governance rationales for companies were developed by ‘law and economics scholars’, interested in growing the discipline of markets over the company’s decision-making process, which involved reviving the purposes of shareholder value maximisation (such had receded in the 1950s and 60s). Footnote 71 Where modern law scholars had emphasised the quasi-public components to corporate governance, the new scholars were keen to amplify neoclassicist ideas about the stark separation of the economic and political spheres (minimising the chance of interventionism). They sought to simplify corporate social interactions as a bulwark against (so-called) shirking, agency costs and discretion at corporate institutions, which the theories discredited as a form of unlawful ‘plundering’ against the interests of members. Footnote 72 Like the political programme, such theories also offered potential for organising life around individual preferences (the good life) and for (crude) economic resolution of social and labour conflicts, which had become a source of creative difficulty for companies and for the under-fire governments of the 1970s.

Importantly, and in a part of the story that is less commonly addressed, the emphasis on deficiencies of government planning and collectivism also filtered into legal scholarship. New kinds of pessimism about law and government grew among the 1980s trend for ‘new public management’ (NPM), which brought the language of economic rationalism to the public sector, and ‘better regulation’, which met the concern about ‘red tape’ and sought to simplify the regulatory environment. Footnote 73 Related but, also, distinct movements arose around the globalised activities of companies that became more ungovernable, as they sought to maximise competitive opportunities in different jurisdictions and markets, made possible by a more liberalised corporate and financial regime (offshoring production, new chances to lower labour and production costs, etc.). New social movements met this problem (of ungovernability) by theorising the concentrated power held by multinational companies (moving beyond Berle’s theories of the modern company) and starting campaigns of direct action (against Nike, Shell, etc.). Footnote 74 Legal scholars, keen to avoid traditional (or stereotyped) regulatory responses and admitting their own generalised scepticism towards constructivist models of law, sought new regulatory mobilisations that built on this notion of direct action (and theories of global corporate power that supported it). Footnote 75 They built visions for enacting more governance in the private sphere, pressing on the incentive to profit and property and decentralising the activities of norm production and discipline. Footnote 76 Such transformations could, scholars reasoned, extend the responsiveness of law over complex, globally distributed, corporate action. Regulation could be re-conceptualised to mean broad kinds of ‘influence’ over others and, thereby, inclusive of sources beyond formalised law and/or state. Footnote 77 Such legal theories were also designed to address long running problems of defective compliance at companies (tick box, avoidant), inspiring new forms of creativity at individual or entrepreneurial units about the social question, itself, thus overcoming law’s more ‘repressive’ qualities. Footnote 78

Repurposing the company has consistently been central to the operationalisation of the legal theories and imagination of new governance. In a landmark article on the subject of corporate fiduciary duties, written in 1985, regulatory scholar Gunther Teubner returned to the suggestion (by Berle and Means, in 1932) that ‘the development of social pressure’ over companies might be a basis for socialising economic behaviour. Footnote 79 Notably, Teubner’s assessment of corporate autonomy, in this context, develops the separation of ownership and control to observe the content or construction of the ‘enterprise interest’, or ‘Unternehmensinteresse’ – a term that Teubner also draws from Rathenau (1917) and his notion of ‘enterprise as such’ [Unternehmen an sich]. Specifically, Teubner undertakes to address the ambiguity about the ‘balance’ between shareholder and community interests (temporarily resolved in favour of shareholders in 1932) by re-developing corporate ‘autonomy’ and the ‘enterprise interest’, as ‘functional’ alternatives for carrying out regulatory functions abandoned by governments within the private sphere. Companies are uniquely placed and incentivised, in this analysis, to operationalise ‘knowledge’ and ‘discovery’ mechanisms of the market, including discoveries about social norms and value preferences. Teubner foresaw a possibility, as private power rose under globalisation, that companies could combine their role as economic actors with social functions, which reached beyond the territorial and planning (or knowledge) limits of states. Companies might, that is, be encouraged to maintain a focus on the negotiation of economic interests (ie, maximising the enterprise interest) whilst also increasing their responsiveness to social pressures, expressed with ‘clarity and force’ in the market or (in his terminology) in the company’s ‘environment’ (Teubner writes the article from a systems theory perspective).

The law and principle of the social contract shifts, in this theory, from setting standards and rights-based negotiation to instituting markets and reflexive processes, which promote ‘externally stimulated internal reflection’ about the pressures, conflicts, and concerns mounting in the company’s environment. Footnote 80 Law is ‘indirect,’ rather than interventionist; it guides or steers a process of market-led reflection and accommodation, extending the gaze of the company and the calculative ‘regard’ of corporate decision-makers to the sources of conflict or ‘irritation’ (this regard is embodied for Teubner in the fiduciary duties). Footnote 81 Such a means to social reflexivity was proposed, by Teubner, to overcome the limitations of legal instrumentalism and of law’s ‘ineffectiveness,’ caused in Teubner’s analysis by a lack of translatability that exists between the operational logic of different functional subsystems (not least, regulators that do not understand or cope with complexity). It was designed, too, to reduce discretion at company boards, ie, balancing the needs of different social groups, moving the governance modus that he developed beyond the stasis of the shareholder versus stakeholder debate. Footnote 82 Organising social ‘integration’ more directly within the market sphere proposed a more effective (responsive) mode of learning about and resolving conflicts, which uses the guarantee of the price mechanism (rather than discretion or thought). It opened itself up in ‘functional’ terms to bettering the guarantee of future needs (than a planner could). Footnote 83 Companies could in this view be encouraged to accommodate stakeholder and social causes, wherever such can be demonstrated to have a bearing on corporate self-interest, conceptualised nominally as ‘gain’ (and usually also the shareholder interest). So, it was possible to observe, in Teubner, the reconfiguration of public government and, also, the stakeholder versus shareholder dichotomy (the double is important) by economically instrumental rationalities, which assume certain creative ‘functions’ (ie, enabling companies to sort through the claims that might attain meaning or presence in markets, using the calculation of ‘enterprise’ interest). Footnote 84

This controversial (private, market-integrative) regulatory structure currently underlies most of the mainstream legal frameworks, expressive of the company’s social role in the UK and EU, including CSR, corporate sustainability and (to a more mixed extent) business and human rights (BHR). It aims at the internalisation, by companies, of externalities (human rights violations, modern slavery, missing tax receipts, preventable carbon, environmental pollution, waste) within the sphere of the enterprise interest. Corporate law frameworks institute the regulatory technique in duties of ‘process’, by which companies and directors are expected to follow and to acquire social ‘reflexivity’ (as regulatory theorists develop the idea of consciousness, built between systems). Footnote 85 The mandates concern the development of corporate regard, reporting, and diligence (RRD) about stated risks (human rights, workers expectations, the environment, etc.), with companies encouraged to consider the short and long term costs to the company of protecting (or not protecting) affected constituents. Footnote 86 It is open to governments and other authorities to add to the list of factors that companies may need to RRD, and, thus, to stretch the systems to new and emerging concerns (to carbon, net zero goals, suppliers’ impacts, modern slavery, etc). Footnote 87 Mitigation is expected or required in the sense of being actionable by the members, acting in the company interest, to the extent that this is consistent with (directors’ assessments of) the company’s ‘success’ (the calculative aspect). Footnote 88

C. Corporate responsibility and regulatory governance: ‘they see no masses’

The present author has written in previous work about the instability of this regulatory model in terms of its ability to create adequate responsibilisation among economic actors for hazards affecting people and planet.Footnote 89 Three sets of (related) problems are worth recounting.

First, where the deployment of economic institutions and incentives smooths the resolution of social conflicts, making it easier ‘to get things done,’ it also transforms the burden of engagement and understanding. Companies (and governments) are released in new governance from substantive forms of consensus building, as such work falls to the enterprise interest; companies adapt to ‘learning pressure’ whilst remaining formally accountable only to shareholders; the price mechanism sorts through claims. Such market accountability is commonly criticised for the weak position that this accords to stakeholders, consulted or listened to, but, also, ignored when contradictions to corporate pricing strategy and/or profit are identified. More subtle is a change in the burdens of creating understanding and responsiveness to the conflicts generated by business, where regulatory governance shifts these important aspects of ‘governing’ towards communities affected or bearing risk. This point sounds counter-intuitive and can be hard to spot, where it is companies that are, in law, expected to conduct RDD and to engage with the process of improving reflexivity. However, if such engagements are to be more than superficial, it is (in practical terms) consumers, civil society, communities and constituents that bear the heavier responsibility of ‘enlightening companies’ in post-state regulatory theory, which maximises (celebrates) individuated mechanisms and the self-reliance of participants.Footnote 90 The claimed ‘freedom’ of the market is reframed, as communities and stakeholders must undertake actions to regulate economic actors by ‘resurrecting interest’, and generating internal reflexion at companies, which ‘cannot be voluntary’ and ‘needs to be stimulated by powerful external forces’ (as otherwise it invites unlawful amounts of discretion from directors, or planners).Footnote 91

This is difficult, extensive and sometimes dangerous work.Footnote 92 Participants commonly relate the time-consuming effort involved in securing influence and remedy. Heightening learning pressure to the point of bearing on corporate self-interest, and before harms are executed or materially visible (publicised), can be a high and sometimes impossible barrier.Footnote 93 Progress is hampered by the complexity of corporate structures and the circumstances of production, which can make knowledge partial (insofar as consumers and others are removed from certain times and places of production). It is often unwound by companies as societal pressure recedes.Footnote 94 More practically, the effort to engage the resilience and courage of individuals in a world that is already tipped in power balances to the autonomy of transnational companies, like PO (Shell, Amazon, etc), is disconnected from the way that this imbalance already makes everyday exchanges more difficult for people (from contesting a gas bill to refusing unsafe work), never mind more ambitious forms of civic regulation.

A second (related, entangled) problem with the market-led modus of corporate responsibility concerns the growing transfer of public ‘authority’ to the private sphere. The observation starts (again) from the potential exposure of individuals and communities in corporate legal orders (as interests to be productively employed but, also, resurrected), and how this exposure is intended to be balanced and mitigated by collaboration across that sphere - with companies, but, also, with other (comparably associated) actors and institutions, including civil society organisations, trade unions, technical experts, etc. This collaborative dimension is important to the institutional imaginary of regulatory governance and its cultivation of normative resources or expertise within the ‘environment’ of the company. It operates as a means of collecting values, community interests and claims together, improving ‘clarity and force’ (the link between Berle and Means and societal constitutionalism, discussed also in this issue by Jean Robé).Footnote 95 Such is designed to develop the ‘functional differentiation’ of worldviews, and to pluralise forms of authority, which is relevant to rigour of regulatory governance and its claim to be nurturing of law and democracy.Footnote 96

A major problem here, however, is the insistence of regulatory governance that differentiation of this order does not ‘weigh’ against competing considerations. Collaborators do not just raise problems with companies, or generate more ‘thought’ about their concerns. They need to find a place within bigger projects of market building (abstraction and commodification), which can ensure that their claims can undergo individuation and translation into the logic specific to the focal system (‘the enterprise interest’). This ‘enterprise interest’ operates within regulatory governance as a mechanism for making claims ‘compatible,’ ensuring closure and decisiveness through the price mechanism.Footnote 97 Such decisiveness and self-organising (spontaneous coordination) is needed according to Teubner’s analysis, in 1985, to reduce the operation of discretion and/or ‘the risk of abandoning the definition of corporate responsibilities to the mercy of the constantly changing result of shifts in the balance of power between social interest groups.’Footnote 98

The wording here is striking where it seems to render exceptional routine aspects of management, attributing ‘creativity’ to the onward resolution of markets and price-based coordination. This fatalism is (again) derivative of functional autonomies of the ‘new governance’ system, ie, the effort to avoid burdening companies with unfamiliar value-systems or rationalities. It lends itself awkwardly to many aspects of corporate responsibility, however, including historic, diffuse and recurrent harms, and to communities that struggle to correspond through the price mechanism and align their own interests with corporate reputation or prove a competitive interest (non-humans, the environment, the poor and precariat, the far away). This imprecision to generating learning pressure is often cited as an advantage (the flexibility and focus that can be brought to regulation through individuation and economic force), but it can create long-standing normative and cognitive problems for companies and society about the real extent of corporate impactfulness; many of the learning exchanges between companies and constituents are fragmented, incomplete and unsuited to the nature of the impacts under scrutiny.Footnote 99 It, also, entrenches companies’ overall power, as social coordinators, economic functionaries and wealth generators, to manage the whole process of social learning and responsiveness in the present and future. This includes the power to announce the overall adequacy of conflict resolution, and ‘respect’ for rights or codes, as fits the enterprise interest.Footnote 100

To these claims, the paper wishes to add a third (related) aspect. It concerns the rising (over time) tendency towards ‘scandalisation’ that has embedded itself in regulatory governance. This is where individuals and social groups seeking to ‘control’ or ‘moderate’ companies in regulatory governance, and in the private sphere, might transform or even shorten normative debate in the effort to improve the public’s chances of impacting the company’s reputation, and influencing behaviour. Participants are forced by the regulatory modus to extend the amount of civic and/or normative expression that can be carried in the market’s (simplistic) communicative exchanges, through the formation of buycotts, boycotts, making threats to reputation (corporate, individual), publicising protests around exit or voice, etc.Footnote 101 Communities are drafted in as stakeholders and encouraged to generate pressure on their own initiative, but are confined by opportunities to create or remove market rewards (as a balance to the open-invitation). Such a narrowing of communication is designed to deliver shocks in attention but can, also, be distortive of normative practices, generalising a boycott mentality and creating different levels of (justified and unjustified) melodrama (due to forced simplification), which is ineffective in terms of stabilising economic systems and/or protecting a general interest (ie, banker bashing). Alternatively, scandal, in distinction to law and duty, loses its grip on the world and energy quickly, meaning that calculation is never far behind in corporate (or peer) responsiveness, even when market-organised discipline and collaboration over corporate targets are successful.

A mandate for normative simplification is a logical extension of the reliance on functional equivalents to law and government, and of the wider refrain that systems theorists have established around thought and the ‘clash of rationalities’ that is expected to occur when one rationality or subsystem tries to influence the other. It is the effort to avoid extended clashes that produces such a high estimation among governance scholars of corporate self-governance and economic functionalism (as a means of improving the social effectiveness of economic action). But governance through economic functionalism also carries the notable frailty of not (always) being generalisable, through not having entered into constitutionally diverse forms of communicative deliberation and exchange, ie, of having justified itself across different subsystems.Footnote 102 Regulatory force in the economic sphere, instead, commonly exhibits (one or more of) market rise and fall, structural ignorance wherever the profit lines inscribe, particularity in responsiveness and ‘therapeutic’ change among private sector actors put under high amounts of commercial pressure (or scandalisation). Implicit too is a dramatic change in the force and function of ‘law’, which is confined to process and to revealing subjects that might be pushed over the line of market integration (ie, command the enterprise interest). Codes, non-binding instruments, guidance and taxonomies do not properly establish subjects of duty and deliberation (when commanding corporate responsiveness), in other words. They establish, rather, fixed points in reality or (in simpler terms) descriptions, which possess few rights, powers and opportunities to actually renegotiate the substantive terms of accommodation (of counting).Footnote 103 Scandal appropriately names the activity and frustration of participants annotated and responsibilised thus (for their own counting) and, also, separated, in kind, from longer civic histories of metaphysical inquiry and norm creation, solidarity and collectivism, etc.

Inequalities in outcome easily form among the forces for accommodation and the responses of companies, which emanate from the tactic of enlightenment, but tend not to attract the tag of discretion or arbitrariness, as the criterion of profit persistently holds. This unevenness is widely evident wherever governments step back from supervision and civic regulators cannot keep up. It is maintained in the call to try and make sure corporate actions and impacts are rendered, through reporting, ‘comparable’, even as the outcomes are inconsistent or (in some cases) even not fully true (ie, materially relatable to experiences of the affected). But the role of law and government remains less to insist on external or substantive control of corporate conduct (eg, less carbon), and more about facilitating the development of market structures within which responsibility (ie, less carbon) might arise as a rational economic opportunity for the company (in its ‘external mobilisation of internal self-control resources’). The difficulty for the civic regulators is in trying to fit (always) more into this idea that change is economic, rather than justified and/or duty-bound, and how this makes some ways of thinking about the world and justice less possible. Such characteristics eventually burden (rather than inspire) a public exhausted by carrying out the function of regulation, unconvinced by the ‘liberties’ of supervising multinational corporations registered off-grid for tax-purposes,Footnote 104 and amidst the larger ‘socialisation of risks, privatisation of rewards’ schema that the corporate economy expounds.Footnote 105

D. The corporation and regulatory governance: the social contract implications

The post-1980s theorisation of the company by (both) law and economics and regulatory governance scholars as a calculative (rather than legal or social) institution is essential to understanding the mandate that companies presently have to safeguard public interests. Often this mandate is underestimated or misunderstood as a more open-ended form of socialisation or enlightenment. Yet, new governance offers to improve on government and collectivist efforts at resolving conflicts by using the company as a decisive economic mechanism (not managerial organ), which can integrate diverse claims and interests (ie, make them compatible). Such a strategy deliberately deters and supersedes efforts to weigh different interests and/or equalise bargaining power between companies and their constituents - a ‘conservative strategy’, according to Teubner’s writing in 1985 (and yet at threat in the UK again from conservative anti-strike laws and the inexhaustible march of consultation). Footnote 106 Corporate power is accepted and reconfigured, in this market-led model of governance, as a site of responsiveness, innovation and learning (‘power is not seen as a source of inequality and injustice but as a social instrument for the effective transfer of decisions’). Footnote 107 Governments, for their part, are expected to ‘regulate internal processes in systems indirectly’, so as to ‘drastically decrease the requirements of cognitive capacities of law and politics, since they no longer attempt to directly influence economic action’. Footnote 108 The state assumes the role of ‘mediator, facilitator, enabler,’ in the post-state regulatory complex, and, because of the commitment made on its behalf to improving the overall compatibility of different rationalities, the ‘skills of diplomats rather than bureaucrats,’ as Julia Black puts things by 2001. Footnote 109

It has been common to read these post-regulatory transformations in the social contract, and the displacement of the state by the ‘global and mezzo’, as pluralist, additive (resourcing law and government with more than state) and progressive for the last 30 years. Yet, recent events, including post-pandemic inequality, profiteering, and climate change create more visibility and suspicion around what has also been depleted or even given away by regulatory governance, amidst its association with the trends of neoliberalism. These wider trends have been recognised (in the words of Bourdieu) as affecting the rigour of ‘collective institutions capable of counteracting the effects of the infernal machine, primarily those of the state, repository of all of the universal values associated with the idea of the public realm.’ They concern, also, the imposition of ‘a sort of moral Darwinism that, with the cult of the winner, schooled in higher mathematics and bungee jumping, institutes the struggle of all against all and cynicism as the norm of all action and behaviour’ (emphasis in original). Footnote 110 The commitment of new governance scholars to ‘decreasing the cognitive requirements’ of law and politics and to ‘no longer attempt to directly influence economic action’ sits awkwardly within this bigger schema of collectivist destruction. This remains the case, despite the strong insistence of some governance scholars that regulatory capitalism ‘has nothing to do with neoliberalism.’ Footnote 111

A social contract perspective is helpful, in this context, to help regulatory theorists to observe more about how, discouraged from ‘providing, distributing, and regulating’, growing corporate power and injustices might be accompanied by government that ‘atrophies’ or fails to develop. Footnote 112 This is where a post-regulatory state becomes increasingly disconnected from outcomes, managed and known about (mainly) in the private sphere. Footnote 113 Such developments aptly characterise recent political economic disorder in the UK, which (of course) cannot be divorced from the ideological investment that some governments make in this direction (ie, resolved to be indifferent to market outcomes; over-investing in commerce and markets as the best means to collective creation). Yet the point that the author is making here is about the separate responsibility that falls to lawyers and policy makers to recognise the justice failures that arise beyond the preference-based authority of market actors, and to radically multiply the means of justification and redress. For this recognition and capacity for attenuation stand to be weakened (rather than strengthened) by a regulatory commitment to ‘reduce the cognitive requirements of law and government.’ Low cognition makes institutions vulnerable to remoteness, structural ignorance, and corruption. It increases the number of situations where regulators depend on the actors and/or systems that they govern for information, deepening conflicts of interest. Deeper, too, is the bureaucracy that attends to the transformation of the regulatory professions into ‘diplomats’, as public practitioners are removed from substantive experience of the economic system’s infractions and pressure points. Footnote 114 They are less trusted as public functionaries – ie, capable of acting on collectivist insight and evidence – as regulatory tasks are always neutralised and excessively fragmented (decentered, individuated), if not undercut by a basic ‘clash’ of interests (individuating harms, undermining understanding of shared or recurrent aspects). Footnote 115

To put the same point another way, in situations of pressing public knowledge (eg, about the contours of a just transition, modern day slavery, pandemics, mass redundancies, etc), it is becoming increasingly strange to watch governments and law makers defer and sometimes (even) protect their ignorance about the general public interest. Citations of complexity (as a justification for governance) look disingenuous after sight of some of the functional equivalents for steering business, which include the recent trend for using public science to develop hugely complex taxonomies and schemas, which corporate and financial actors, then, need to be pressured to adopt. Footnote 116 Similarly, where the tactic of ‘enlightening’ corporate decision-makers has not proved to be that effective in terms of changing company behaviour, after fifteen plus years, low cognition would appear to be misguided in the sense of constantly degrading the potential for recognising and interrupting a word (and affect) sludge. Footnote 117 Of course, such a deferral of public power and government (collectivism) references a hope that, somewhere, more dynamic, knowledgeable and motivated actors take an interest in theconsequences, and that exchanges in the private sphere can still qualify as such a place (despite the limits imposed by knowledge of circumstance, scandalisation and individuation). But long-term deference in this direction puts into decline (rather than grows) law’s creative spirit, distorting the normative and political dimensions (exchanges, visibilities) of building a world that is just. Footnote 118 Over time, it also undermines institutions and respect for democratic government and the rule of law (as was evident at P&O). Such weakens the authority of institutions where suspicion of collectivism and bureaucracy prevents rational organisation, as well as the accumulation of experience among governments and regulators, increasing the risk of their failure.

Such prospects for the status of government and the function of law attract the legal scholar’s attention, as a group of equally serious (if not more?) issues to the problem of ‘law’s effectiveness’, which motivated the transformations in regulatory theory in the 1980s. They suggest ongoing difficulties with contextualising companies in their social and regulatory aspects among markets, and a possible breach in some essential elements of the social contract with business when granting a monopoly of public authority to corporate actors whilst squandering legitimate government (and regulatory) power.

2. Rethinking the social contract and corporation

This second part turns the historical perspective on the company around. It looks from the turbulence of the 1930s in the opposite direction, towards events that informed the conceptual arc of the company’s socialisation. It collects fragments of the company’s legal history to form an alternative sense of a past for corporate social regulation and to raise this collage to a higher degree of reality. Footnote 119 The ambition is to work against the necessity of the way things are (ie, oddly arranged, normatively passive, unjust). It also compounds the gist of an essay written by Keynes in 1926 about the social contract and ‘the end of laissez-faire,’ where Keynes talks about an economic dogma that ‘had got hold of the educational machine; it had become a copybook maxim. The political philosophy, which the 17th and 18th centuries had forged in order to throw down kings and prelates, had been made milk for babes,’ Footnote 120 after a line of political philosophers were to ‘retire in favour of the businessman – for the latter could attain the philosopher’s summum bonum by just pursuing his own private profit.’ Footnote 121 Recovering powers of collectivism, if not the ‘emancipation of the mind,’ needed ‘thought’ for Keynes about the constructive arrangements and implications of human economic affairs, and ‘a new set of convictions, which spring naturally from a candid examination of our own inner feelings in relation to the outside facts.’ Footnote 122

This ‘thought’ project is resurrected around the company and the social contract in Part 2, and centred on the industrial modernism of Walter Rathenau, as an origins figure in the modern lineage of socially conscious corporate law and institutions (Rathenau’s work is referenced by Berle and Means, in 1932, and also Teubner). Part 2 seeks to revisit Rathenau’s thinking at the end of the war (when he was writing about the company) and also earlier (a more formative period), as a means to recover what was original about the organisation that he observed. It uses a collage built around Rathenau, his circumstances and associations, to further question the way that the social contract with business has developed, as a functional support for corporate autonomy that fails and frustrates many, and to argue that such is historically discontinuous with progressive law and political economy.

A. Walter Rathenau and the corporation: the making of the modern company

When German industrialist, scholar and early Weimar politician Walter Rathenau (1867–1922) wrote about the modern industrial corporation it was 1917. Footnote 123 Rathenau had recently been involved in the German war effort as head of Germany’s Raw Materials department where he was involved in wartime planning, including the national distribution of economic supplies. Footnote 124 He was recruited to this role for his experience as an executive and industrialist at the family company Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft AG (AEG), where he had been a board member since 1899 (he also held positions at many other companies). Footnote 125 After the war, Rathenau wrote about his belief that public benefits were among the significant outputs of industrialisation but, also, of the corporations that were at the helm of European economies from the end of the 19th-century. The scale at which large companies were able to touch public interests in the age of ‘mechanisation’, Footnote 126 combined with the ‘de-personalisation of ownership’, Footnote 127 was creating new centres of public governance and autonomy at the entity level (‘the enterprise as such’). Footnote 128 Rathenau related this new autonomy, at the corporation, to a retreat in shareholder interventionism and to the capacity within the corporate institution for ‘creation’ (the ‘faculty of envisioning what does not exist’), ‘responsibility (‘we encounter an official idealism identical with that which prevails in the state service. .. the executive instruments labour for the benefit of times when. .. they will long have ceased to be associated with the enterprise’) and ‘technocratic management’ (‘the undertaking itself, now grown into an objective personality, maintains itself, creates its own means just as much as it creates its own tasks’). Footnote 129

Throughout his writings about the economy, Rathenau is careful to distinguish the public or ‘community’ interest at companies from (purely) private property and the (command of the) shareholder interest, which was understood, by him, as erratic, ill-informed and too remote from an understanding of the company’s day to day operations to be informative (ie, incompetent). Footnote 130 Rathenau steered at the same time away from economic liberalism, wherever he worried about the ‘global idolatry of the market,’ the spiritual worth of purely material achievement, and the propensity of material processes or abstractions like efficiency to degrade consciousness and the world (including nature). Rathenau concerned himself, too, with the growing inequity of the modern economic system and suggested that ‘if we have availed ourselves of mechanisation for the sake of its integrating powers, we have now to call it to account, concerning its secret tendencies to promote disintegration.’ Footnote 131 ‘Too long,’ Rathenau observed, has ‘the rationalist notion of individual rights and liberties’ proved ‘tardy and mutinous in yielding to collective needs and requirements, which require regulation.’ Footnote 132 Rathenau highlighted the possibility that societies could usefully increase state regulation and supervision over companies for their ‘material strength and equalising energy’ (emphasis added) as the latter’s industrial capacities and influence (autonomy) grew. Footnote 133 Indeed, contrary to the classic mid 19th- century characterisation of the laws for incorporation, which sought to liberate companies from government charter, and catalyse the private sphere, Rathenau viewed consumption and production ‘not as private affairs but as matters of public interest,’ rooted on some level in the ‘state’ or common institutions, which the individual ‘did not create.’ Footnote 134

Rathenau was assassinated by the far right in Germany, in 1922, whilst occupying the post of a minister in the Weimar Government (foreign minister). He would not live to see the new social and economic order that he thought was emerging. Footnote 135

The collapse of Weimar and subsequent ascendancy of the Nazi party in Germany saw Rathenau’s books burned by the Deutsche Studentenschaft (Dsf) as ‘un-German’ (Rathenau was Jewish) in 1933. Footnote 136 His ideas about the corporation and community interest, however, were still entered into discourse about company law and regulation in Germany, via the work of scholars interested in corporate institutional theories. Footnote 137 Nazi-era law reforms sought to gain more control of the economy, linking ‘company interest’ (which in some quarters of legal scholarship grew out of Rathenau’s conception of the ‘enterprise as such’) and national interest, eroding shareholder rights – moves that created lasting suspicion about state involvement in private enterprise. Footnote 138 Yet, around the same time, other scholars, including John Maynard Keynes in England and Berle in the US, would also take an interest in Rathenau’s contemplation of autonomy at large companies and make it an ally of the ‘new industrial state.’ Footnote 139 ‘A point arrives in the growth of a big institution – particularly a big railway or big public utility enterprise, but also a big bank or a big insurance company,’ said Keynes in 1926, ‘at which the owners of the capital, ie, its shareholders, are almost entirely dissociated from the management, with the result that the direct personal interest of the latter in the making of great profit becomes quite secondary.’ Footnote 140 Berle, as Part 1 illustrated, developed Rathenau’s notion of depersonalisation in the ownership of companies to observe the separation of ownership and control, and the company interest as a faculty that might encompass responsibilities to communities or stakeholders. Such theories have often been taken as the origins point for the later fascination with corporate self-government and autonomy, which later regulatory theorists pick up and redevelop (as responsive companies, reflexivity – see Part 1).

Yet, Rathenau’s reflections on corporate autonomy come chronologically before Berle and Means, and perhaps offer a different historical axis for thinking about the future of the social contract and corporation (sending us somewhere different from where we are). Writing about the company at the end of World War I, and being praised for his work as a government economic planner, Rathenau did not anticipate anything like the generalisation of corporate governance questions, or the domination of markets as a means to societal integration. In fact, his text shows few inklings towards corporate self-governance, or for ‘pressuring’ business in the economic sphere as a means to bettering regulatory outcomes. Rathenau shared the interest of the Americans in ‘enlightened administration’ and wrote at some length about his interest in rational organisation. He highlighted the satisfaction that business managers experience when addressing, with technologies of the machine age, public interest (the ‘joys’ of industrial creation). Footnote 141 Yet, his work never sways substantively towards corporate law as ‘constitutional law for the new economic state’, or studies the implications of privatising the social contract and instilling government at corporate bureaucracies and/or among their constituents (ie, he does not stride into the shareholder versus stakeholder debate).

Instructive in this context is the era that Rathenau was living and writing within. Despite there being only 15 years between Berle and Rathenau’s writing, different worlds and generations collide in the recanting of Rathenau’s corporate law theories and reflections in the Anglo-American context (from the 1930s and beyond). Rathenau, more specifically, was born in 1867, Berle and Means 1895 and 1896. Keynes, for reference, stood between the two sets of contributors and was born in 1883. Berle, between 1930 and 1932, was writing about company law and individualism at the end of the roaring twenties after the Great Crash, and ex post to an extended period of speculation (where there was ‘only the pursued, the pursuing, the busy and the tired’, F Scott Fitzgerald). Footnote 142 Berle and Means were also only born a few years before the English judgement of Salomon v A. Salomon and Co Ltd in 1897, Footnote 143 and lived wholly within the era of general incorporation laws that took the company private during the second part of the 19th-century. Footnote 144 The Rathenaus, by contrast, would have been among the first business owners in Germany seeking to avail themselves of the limited liability business form (AEG was incorporated in 1882 by Rathenau’s father, Emil Rathenau). Yet, as a family, they (the Rathenaus) also lived and worked much closer to the pre-existing system of state-chartered companies (Emil was born in 1838 and had various ventures before AEG), considered ‘public’ to the extent that they received their licence and accountability from government.