1. Introduction

Europe, and indeed Humanity, are facing a myriad of difficult challenges. The climate and environmental emergency pose existential threats to life on earth,Footnote 1 while growing inequality seems the root of many economic and political ills.Footnote 2 It is increasingly clear that GDP growth neither lowers inequality (at least in the West)Footnote 3 nor betters environmental outcomes.Footnote 4

The negative outcomes described are the result of a complex interplay between various socio-economic processes and policies, including economic globalisation, the loss of regulatory power by nation states in the pursuit of ‘(international) competitiveness’, rampant financialisation, deunionisation, regressive tax policies, and so forth.Footnote 5 In Europe, the Lisbon agenda,Footnote 6 the monetary unionFootnote 7 and the asymmetrical development of the internal market programFootnote 8 have also played a role. More often than not, it is neoliberal policy prescriptions – as popularised by Hayek, the Chicago boys, Margaret Thatcher or Ronald Reagan – that are considered responsible for these outcomes.Footnote 9 Placing privatisation, deregulation and liberalisation at the centre, this neoliberal route to prosperity became hegemonic in Europe in the second half of the 1990s when social democratic governments headed its implementation.Footnote 10

One central driver behind the model of economic development where GDP growth is paired with growing inequality and environmental degradation has been the change of both the purpose as well as the institutional context inhabited by one core private actor – the corporation.

In the neoliberal imaginary of prosperity, the corporation is often viewed as the main driver of progress. As a result, policies which support the corporation’s operations, growth and expansion became the political priority.Footnote 11 Paradoxically however, this ‘full steam ahead’ approach for the corporation came with a concomitant narrowing of interests and purposes that the corporation is supposed to serve, creating the ‘self’ in the ‘self-interested’ that ultimately eschewed everything but share prices.Footnote 12

Clearly, as corporate scholars have reminded us time and time again, the ‘shareholder value’ paradigm has never been institutionalised via company law.Footnote 13 On a narrow reading, there is nothing in corporate law itself, at least in Europe, that forces corporations to take such a narrow understanding of corporate interest.Footnote 14 And yet, the combination of several distinct institutional mechanisms, such as financialisation, quarterly reporting and management remuneration, has made shareholder value a social norm.Footnote 15 Corporate law scholars have also played their role in institutionalising this paradigm; the enthusiasm with which they have devoted their research to exploring how to align the interests of shareholders and managers has made ‘shareholder primacy’ into the dominant discourse in the field.Footnote 16

The ever more concerning impacts of contemporary corporate governance have not passed unnoticed. The business and human rights movement has booked modest successes with the introduction of several international soft law instruments which attempt to limit the global impact of business on human rights (the United Nations (UN) Principles,Footnote 17 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Principles).Footnote 18 More recently, several nation states (as also committed to under the UN principles)Footnote 19 have introduced various sector specific ‘due diligence’ laws.Footnote 20 At the level of the UN, a Binding Treaty on Business and Human rights is currently being negotiated – if with lukewarm support from developed countriesFootnote 21 – aiming to develop a more effective framework for establishing liability for human rights violations.Footnote 22

A. The EU’s corporate governance ‘file’

The European Union enters this space of ‘business and human rights’ due diligence relatively late.Footnote 23 It has introduced obligatory due diligence in specific high risk sectors, such as timber,Footnote 24 and conflict minerals.Footnote 25 Furthermore, in 2014 it put forth a more general measure, the ‘non-financial reporting directive’,Footnote 26 which required the largest corporations to publish ‘non-financial information’ related to environmental protection, the treatment of employees, human rights, anti-corruption, bribery, diversity on company boards, and any diligence procedures throughout the supply chain – if they had any.Footnote 27 The directive was primarily successful in revealing that very few large companies actually undertook any due diligence across the chain.Footnote 28 Somewhat more promisingly, the EU has also started developing a ‘Green finance’ package. Whilst still in the ‘reporting paradigm’, it contained some important tools for steering investments towards green initiatives.Footnote 29

All these initiatives found an overarching policy framework in the 2019 European Green Deal. Despite considerable criticism, the European Green Deal remains a first-of-its-kind policy framework which aims to develop a systematic approach for the transition to a more sustainable economy.Footnote 30 It starts from the premise that transitioning to a sustainable economy will require us to change the ways in which we produce and consume. It operates across core sectors (energy, transport, food etc) as well as general market rules (consumer policy, corporate governance, public procurement, subsidies etc) in order to reorient economy.

In such a context, the question of how business organisations are run has become paramount.Footnote 31 The European Commission started revising its corporate governance framework and aligning with the Green European Deal in 2020. This action took place on two fronts. First, an overhaul of the 2014 non-financial reporting directive was in order, so the Commission – specifically DG FISMA – started preparing the corporate sustainability reporting directive. While the primary objective was to help investors make more sustainable investment decisions, the transparency element was also expected to have a broader disciplining effect on corporate behaviour. Somewhat later, the Commission also opened a ‘due diligence’ file, under the directorship of DG Justice.Footnote 32 Going beyond transparency of ‘material information’, the due diligence framework was expected to set material standards on the corporate action of large European, and even larger non-European, firms.

However, the Commission’s ambitions went further than just due diligence – something which became obvious from the preliminary stages of the due diligence proposal, which started with commissioning a report on the ‘directors’ duties and sustainable corporate governance’.Footnote 33 Tasking the reporter to explore the impacts of short-termism in corporate governance, the Commission appeared interested in tackling the interplay between financial markets and corporate governance. These efforts seem to have followed up on the European Banking Authority report from December 2019, which found some evidence of short-termism in relation to corporate sector, and less so in the banking sector, precisely thanks to the changes in the underlying legal and governance framework: ‘Changes in banking regulations since the financial crisis, notably on remuneration, have been designed specifically to counter undue short-termism, and the outcomes of these changes themselves are reflected in this report’.Footnote 34

The Study on ‘directors’ duties and sustainable corporate governance’ was delivered by Ernst&Young to the Commission in July 2020, finding that short termism is indeed strongly present in the EU’s corporate arena and leads to both unsustainable choices in terms of the company’s bottom line (the lack of investment in innovation and people) and irresponsible behaviour towards all other stakeholders and environment.Footnote 35 In the same year, the European Parliament (in reaction to this and other studies and initiatives) also called on the European Commission to revise the Directive on non-financial reporting and propose a more robust ‘sustainable corporate governance’ framework that would solve some of the identified issues.Footnote 36

In response, Spring 2021 saw the Commission publish a so-called inception impact assessment (‘a roadmap’) which outlined ideas of how to move forward in the field of corporate governance.Footnote 37 The roadmap was opened to public consultation and became a basis for the assessment of the first ideas by the Commission’s ‘regulatory watchdog’, the Regulatory Scrutiny Board.Footnote 38

The inception impact assessment recognised the short-termism as a systemic problem and envisaged a relatively broad range of interventions in field of company law to ensure ‘sustainable value creation’.Footnote 39 These interventions included several previously unthinkable hard law measures, including defining directors’ duties and liabilities, regulation of the composition of the company board(s) as well as the remuneration of their members, the inclusion of sustainability in business strategy and the provisions for stakeholder involvement. The Commission had thus intended to remedy several of the systemic constraints on the operation of public corporations via company law. Even if these constraints may not have originated in company law in a narrow sense, market operation could not be expected to remedy them – according to the European Commission – and resultantly hard law changes in company law were necessary.

However, the Commission’s ambitious agenda faced notable opposition. According to the report of the Corporate Europe Observatory, during the preparation of its proposal DG Justice refrained from extensive consultation of the business communityFootnote 40 – something that stands in contrast to other EU legislative proposals. In the wake of the inception impact assessment then, the industry, some Member States (especially Nordics, such as Denmark), as well as many corporate law, finance and economics scholars, set out a broad challenge to the Commission proposal. Still, in the end it was the Commission’s internal body, the Regulatory Scrutiny Board, that actually forced it to cut back most of its more ambitious proposals.

The Regulatory Scrutiny Board (RSB) rejected the Commission’s inception impact assessment on several grounds, the most important one being that the Commission had not shown that the problem – unsustainable corporate governance – existed at all.Footnote 41 It called on the Commission to provide evidence on both the problem description as well as its impacts. DG Justice thus went back to the drawing board, ‘strengthened’ this time with new co-lead Thierry Breton, from DG Internal Market, as guarantors that industry interests will be better safeguarded.Footnote 42 And yet, the newly drafted full impact assessment, in a quite exceptional move, was again rejected by the RSB in November 2021Footnote 43 on the grounds that it still did not sufficiently demonstrate the existence of the problem nor the solutions.Footnote 44

The final proposal for ‘sustainable corporate due diligence’, published in February 2022, is a considerably watered-down version of its previous impact assessments. As the Commission admits:

The Directive is more focused and targeted compared to the preferred option outlined in the draft impact assessment. The core of it is the due diligence obligation, while significantly reducing directors’ duties by linking them closely to the due diligence obligation.Footnote 45

To start, the title of the measure is not as broad – with ‘sustainable corporate governance’ being narrowed ‘corporate sustainability due diligence’.Footnote 46 This limiting of ambition also meant that more structural interventions via company law into the incentives driving public companies toward short-termism more generally were, for the large part, left out. Thus, directors’ duties and liabilities, as well as management remuneration, are mentioned practically only in passing. At the same time, stakeholder involvement has almost disappeared. The sustainable corporate strategy has been watered down, with no reference in the proposal to directors’ duties to include science-based targets nor any specific requirements on the content of transition plans or strategies. As the Commission explains, ‘Further reaching specific directors’ duties that had been put forward in the impact assessment are not retained.’Footnote 47

This may not be, however, the last round of cuts. The Council has recently produced its position with regard to the due diligence file, further cutting on the obligations set out by the Proposal.Footnote 48 As it concerns climate obligations, any link to remuneration of the directors has been removed entirely in the Council’s position (Article 15 of the Proposal). The position also leaves out any references to director duties, including a reference to the duty of care (Article 25 of the Proposal). In turn it introduces ‘clarity’ with regard to civil liability, linking liability to intentional breaches and strong causality of the thinned-out duties – making sure that victims do not have it any easier (Article 22 of the Proposal). As concerns the culprits, it is the Nordic states whom we can thank (again) for the emaciation of the Position.

In contrast, the European Parliament has thus far produced a couple of drafts of the committees’ reports. The leading JURI committee, for instance, seems to be going in a markedly different direction to the Council – strengthening the directors duties, making stronger links between environmental performance and remuneration, calling for more stakeholder involvement and giving teeth to civil liability.Footnote 49 Once the Parliament has finalised its position in March 2023, the trialogue can start.Footnote 50 In any case, it is worth noting this interesting split between the EU institutions, which goes across simple political-ideological lines.

2. Imaginaries of prosperity and the corporation

After the second negative opinion of the Regulatory Scrutiny Board, the Proposal should have been taken of the table (in principle). Yet, when the Commission decided to go forward with the some version of the Proposal, no one was really surprised. In fact, most pundits expected it. The reason is, I will suggest, that there is currently a broader shift in faith as to the capacity of the market to deal with social ills, such as the ones targeted by the Proposal. The Commission recognises this:

The market and competitive dynamics together with the further evolution of companies’ corporate strategies and risk management systems are considered insufficient and as regards the assumed causal link between using corporate sustainability tools and their practical effect in tackling the problems.Footnote 51

In the following pages, I will argue that, however trimmed down, the Proposal suggests that the days of the neoliberal imaginary of prosperity may be numbered. When the Commission and the Regulatory Scrutiny Board disagreed, they did not do so simply on how to address the problems we face, but rather on the existence and the nature of the problems. Such a major transformation of the problem definition indicates a deep shift in the understanding of how economy, politics, or government works and the ways to act on it – legally, ethically and technically. This shift, I will suggest, is the shift in the imaginary of prosperity, that is, in the set of background understandings of how we as a society can achieve a better, or more liveable, future. In other words, the clash between the European Commission and its own ‘regulatory watchdog’,Footnote 52 and possibly between the Council and the Parliament in the future, should not be seen as the result of simple differences in ideological preferences. Rather, these institutions do not share anymore the background ‘imaginary of prosperity’, that is the background understanding of how the economy works, and who and how should deliver us to a better future.

In fact, the modern history of democratic capitalism – going back some 150 years at least – should be understood as the oscillation between different ‘imaginaries of prosperity’ in Europe. This has seen public and collective actors on the one hand, and private actors on the other, alternately being placed in the driver’s seat of progress.Footnote 53 Before WWI, as well as after 1980, the shared social imaginary placed the market, private actors and the ‘private sphere’ in the driving seat of prosperity. In these imaginaries of privatised prosperity, a better future comes through the operation of the market, technology, quantification or individual strive and is mostly external to the domain of law and politics. The how of progress in such an imaginary requires us to ‘untie the hands’ and free the ‘self’(interest) of those who are rooted in these domains, so they may be free to bring about better futures. Clearly, the dirty secret was always that ‘untying’ of private actors comes with a lot of ‘social engineering’,Footnote 54 in an attempt to unleash not so ‘natural’ potential of the private sphere.

The other imaginary of prosperity – the one that predominated foremost in the midst of the 20th centuryFootnote 55 and that I believe is rearing its head again today – places its trust in public and collective institutions as the drivers of progress, both in economic and political life. In these imaginaries of collective prosperity, it is the realm of politics and law that is seen as the primary driver of social change and progress.Footnote 56 Such imaginaries are ‘constructivist’, in the sense that Hayek detested,Footnote 57 using law and policy as a means to change economic structure, power imbalances or distributions of wealth, voice and power.

The oscillation between collective and privatising imaginaries of prosperity has always found its institutionalised expression across contemporary political economies – including the corporation.Footnote 58 When the privatising imaginaries of prosperity prevailed in the 19th century (in most European countries at least), the corporation was privatised via three institutional routes: namely, the shift away from the concession to the incorporation by registration, from partners to shareholders, and from full liability to limited liability.Footnote 59 The social excesses of this first round of privatisation were then reined in (at least in part) after the great economic crisis and more clearly post WWII with the first ‘collectivisation’ of corporation. This was accompanied by a stress on the social responsibility of the business and directors, the general ‘suspicion of profit’, and, fundamentally, a very high taxation of corporate profits.Footnote 60 These arrangements have been challenged and reversed later, during the neoliberal privatisation of corporation, that took place from the 80s onwards. This is something I will discuss in the following sections.

Importantly, the concept of ‘imaginaries of prosperity’ that I propose in this article are not the expression of simple political ideologies – that of the right or the left. Rather they present the hegemonic conceptualisations of the relations between economy and politics, which in turn (re)define the political centre, including how we understand left and right, public and private, as well as the individual and collective. The ‘paradigmatic’ nature of the oscillation between different imaginaries of prosperity is linked to the rearticulation of problems that we as a society have to care about, accompanied with a renewed collection of solutions, changes in the necessary expertise, ethical commitments and the pre-understanding of both the collective interest and the individual (and in this case corporate) ‘self’.

For instance, the neoliberal imaginary of privatised prosperity became dominant – ie deeply shaping political, societal and cultural contexts and discourses – at the moment when social democratic governments in Europe ‘bought into it’.Footnote 61 Also the imaginary of collective prosperity, which was previously dominant post WWII, shaped the positions across the political spectrum and society, including (as we will see) business leaders.Footnote 62 To usher in a new imaginary of collective prosperity, societies would have to move away from the previous neoliberal social consensus, adopting a different basic understanding of how the market and economy, government, politics, nature and law work and should work, while placing the new ‘We’Footnote 63 in the driver’s seat of prosperity.

While many expected this shift away from the neoliberal imaginary of prosperity to take place after the 2008 financial crisis, this has not been the case.Footnote 64 In fact, it was not until the Covid crisis that the imaginary started changingFootnote 65 and not until the war in Ukraine and current energy crisis (deeply related to the climate crisis) that a broader shift is actually becoming more apparent.Footnote 66 What this emergent social consensus, this new ‘We’, may look like once articulated is still unclear; different social forces are trying to give shape to that what is still not fully born.Footnote 67 In Europe, it is the European Commission and the European Parliament – in sync with several of its Member States – that seem to be trying to articulate the new progressive imaginary of collective prosperity, in line with the European Green Deal. At the same time, more nationalistic forces are also on the rise. The recent victories of extreme right parties in both Sweden and Italy open the spectre of a far less progressive collective imaginary that builds on well-rehearsed nationalist tropes, where the tiny nations attempt to propel themselves to a better future mainly by by doubling down on anti-immigrant rhetoric.Footnote 68

This article will try to start formulating what the new progressive imaginary of collective prosperity in the EU may look like. The corporate governance file is particularly suitable as a case study, for it concerns the prime agent of the neoliberal imaginary of prosperity: the corporation. The corporation has been the foremost private actor – intended to lift us all into a better future, while entire ‘state apparatuses’ have been mobilised to facilitate its innovativeness and dynamism – including the provision of large tax cuts for corporations and their ‘investors’, de-regulation, privatisation, international trade agreements, the free movement of capital and financialisation, just to name a few. Therefore, an attempt at more fundamental of reform the corporate subject initiated by the technocratic European Commission obviates the shift that we are seeing in many other fields – the return of the government.

3. A thorny path away from the neoliberal imaginary of corporation in the EU

A. Neoliberal corporate self

Most stories about the neoliberal corporation start with Milton Friedman. This one is no exception. In his 1962 book, and the shorter 1970 restatement of his argument in The New York Times, Friedman launched what in a decade or two was to become the dominant understanding of the purpose of corporate activity: The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits.Footnote 69

Friedman’s position at the time of writing was nowhere close to hegemonic, and certainly not institutionalised in either social or economic practices. Quite to the contrary, Friedman responded to what he saw as widespread and counter-productive calls for ‘social responsibility’ by both business and policy leaders, suggesting that:

The businessmen believe that they are defending free enterprise when they declaim that business is not concerned ‘merely’ with profit but also with promoting desirable ‘social’ ends; that business has a ‘social conscience’ and takes seriously its responsibilities for providing employment, eliminating discrimination, avoiding pollution and whatever else may be the catchwords of the contemporary crop of reformers.

Yet, the advocacy of corporate social responsibility was, according to Friedman, preaching pure and unadulterated socialism. Footnote 70

As a phenomenon, corporate social responsibility was, in Friedman’s view, mainly an expression of the damaging tendency to ‘spend someone else’s money’:

In a free-enterprise, private-property system, a corporate executive is an employee of the owners of the business. He has direct responsibility to his employers. That responsibility is to conduct the business in accordance with their desires, which generally will be to make as much money as possible while conforming to their basic rules of the society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom.Footnote 71

What Friedman was arguing against was the first collective understanding of corporation – the corporation as an actor not merely interested in profit, but rather a socially responsible collective actor. Friedman hereby argued against the widespread social consensus, which – as the consensus definitionally does – included some unnatural allies such as business leaders themselves. The reasons why Friedman and Friedmanites were successful are both complex and well known.Footnote 72 In the most simple of terms, Friedman’s ideas were an expression and co-constitutive of a broader shift toward a new imaginary of privatised prosperity.

Not only did Friedman believe that new corporate self’s strive for profits would unleash the power of self-interest to propel the world to the better future, he also trusted that it would provide a more reliable metric with which the owners of the business – the shareholders – could hold managers to account:

Needless to say, this does not mean that it is easy to judge how well he [the manager] is performing his task. But at least the criterion of performance is straight-forward, and the persons among whom a voluntary contractual arrangement exists are clearly defined.Footnote 73

Today, the last strongholds in defence of shareholder primacy and shareholder value are precisely that they constitute the most effective ‘accountability mechanisms’.

What happened in the following decades is rather a commonplace knowledge, in corporate circles at least. The ideas on the corporation that Friedman articulates in these pieces became the dogma of company law and corporate governance, particularly in the 90s,Footnote 74 and were institutionalised often indirectly via many legal, financial and governmental norms and practices.

In Europe, it was from the end of the 90s that we saw the growing influence of ‘shareholder primacy’ thinking, alongside a broad adoption of self-regulatory instruments modelled on the UK’s corporate governance ‘codes’.Footnote 75 This shift came from several parallel developments: the Commission’s challenges to the ‘golden shares’ cases,Footnote 76 the Centros line of CJEU cases at the turn of the century,Footnote 77 the development of a ‘capital markets’ union in the EU from the end of the 90sFootnote 78 and finally, the strengthening of shareholder rightsFootnote 79 in the 2007 directive and its revised version of 2017.Footnote 80 It was also around the same time, in 2001, that the Commission abandoned the lingering project of giving a greater role to workers in the governance of firms, entirely abandoning the 5th directive on corporate structure.Footnote 81 And while the continental Member States, especially Germany, may have mounted some resistance to the neoliberalisation of EU corporate law in the early 90s, the model became increasingly uncontroversial first in corporate law circles, and then more broadly in policy.Footnote 82

B. What is corporation for? Expanding corporate interests, purposes and duties

The major problem with the imaginary of privatised corporation, with its focus on profit as a clear ‘criterion of performance’, was that it did its job all too well. With share price becoming the main orientation of managers in the past decades, ‘cost cutting’ on all fronts,Footnote 83 compounded with operations on financial markets (eg share buy-backs),Footnote 84 became the main way of doing business.Footnote 85 This had consequences for both the environment (outsourcing to low standard jurisdictions, the extreme throughput of material and energy, polluting where cost effective etc)Footnote 86 and labour (the redistribution of share between labour and capital – towards the capital).Footnote 87

In one Ernst&Young study, these dynamics are shown to have translated in several ‘drivers of short-termism’:

-

1. Directors’ duties and company’s interest are interpreted narrowly and tend to favour the short-term maximisation of shareholder value;

-

2. Growing pressures from investors with a short-term horizon contribute to increasing the boards’ focus on short-term financial returns to shareholders at the expense of long-term value creation;

-

3. Companies lack a strategic perspective over sustainability and current practices fail to effectively identify and manage relevant sustainability risks and impacts;

-

4. Board remuneration structures incentivise the focus on short-term shareholder value rather than long-term value creation for the company;

-

5. The current board composition does not fully support a shift towards sustainability;

-

6. Current corporate governance frameworks and practices do not sufficiently voice the long-term interests of stakeholders;

-

7. Enforcement of the directors’ duty to act in the long-term interest of company is limited.Footnote 88

The European Commission framed the problem with the neoliberal corporation in this way:

many companies, in particular those listed on regulated markets, face pressure to focus on generating financial return in a short timeframe and redistribute a large part of the income generated to shareholders, which may be to the detriment of the long-term development of the company, as well as of sustainability.Footnote 89

Furthermore, the ‘company as a whole, the company interest and directors duties are interpreted narrowly favouring maximisation of short-term financial value’,Footnote 90 This leads to business strategies, which

hamper investment crucial for the sustainability transition, into productive facilities, innovation, upgrading and employee retraining. It may also contribute to income inequality as short-termism creates pressure to depress non-executive wages and employees often do not benefit from shareholder payouts.Footnote 91

Similar sentiments have also been expressed by the European Parliament, which argues that even if company directors have the duty to act in the general interest of the company, this has far too often been understood as the financial interests of shareholders.Footnote 92

Both the European Parliament and the European Commission concluded that what we need is a different kind of corporation. We have created firms and markets that favour short term, rather than long term perspectives – even against companies’ own best interests. Instead, as the European parliament suggests, ‘companies should make a more active contribution to sustainability as their long-term performance, resilience and even their survival may depend on the adequacy of their response to environmental and social matters’.Footnote 93

Adopting this long-term horizon will require, according to the European Commission, ‘encouraging businesses to frame decisions in terms of environmental (including climate, biodiversity), social, and human impact for the long-term, rather than on short-term gains.’Footnote 94 Such responsible corporate behaviour cannot be driven, however, by

Voluntary action [that] does not appear to have resulted in large scale improvement across sectors and, as a consequence, negative externalities from EU production and consumption are being observed both inside and outside EU.’Footnote 95

It is both the impact of sustainability challenges on the company’s long-term performance as well as the company’s impact on the planet – double materiality – that should guide corporate behaviour.Footnote 96

In order to get there, both the European Commission and the European Parliament in its 2021 position have proposed two sets of measures when it comes to ‘sustainable corporate governance’. One set of measures, which are better surviving the push back, are the due diligence measures. In line with a longer recent history of international (soft law) efforts to hold companies accountable for their supply chains, and several Member States regulating due diligence nationally, the EU had a responsibility to act in order to prevent distortions of the internal market. This time around, however, the due diligence was not meant to be only a voluntary commitment but be paired with administrative and civil liability: with the latter bound to have hard times in the Trilogue.Footnote 97

The other set of measures, which primarily tried to address some of the more systemic ‘drivers of short-termism identified not least by the Ernst&Young study,Footnote 98 came under the heading of ‘director’s duties’. Alongside the articulation of the problem and the description of the corporation, it is these proposals that were placed under the most significant pressure – today being entirely left out of the Council Position.Footnote 99 This included issues such as the negative impact of remuneration incentives, lack of integration of sustainability in business strategy and a duty of care with regard to its stakeholders – that is, not only the one pertaining to the chain, but also its own workers, consumers, and communities at home:

Company directors to take into account all stakeholders’ interests which are relevant for the long-term sustainability of the firm or which belong to those affected by it (employees, environment, other stakeholders affected by the business, etc), as part of their duty of care to promote the interests of the company and pursue its objectives; company directors to define and integrate stakeholders’ interests and corporate sustainability risks, impacts and opportunities into the corporate strategy – following appropriate procedures – with measurable and time-bound, science-based targets where relevant, including as regards climate targets aligned to the Paris agreement, biodiversity and deforestation targets, etc. and according also to the company’s size and activity, and to implement such strategy through proper risk management and impact mitigation procedures;Footnote 100

This set of prescriptions that both the Commission and the Parliament had in mind required a more significant departure from the neoliberal corporate self, in at least as they expanded the duties of care of the company directors to a rather broad range of ‘social responsibility’ obligations – under the threat of administrative and civil liability. The duty of care was directed towards all its stakeholders, in value chains and at home. It included the provision of measurable scientific targets on the basis of which companies could be actually held to account as well as proper mitigation strategies – all of which directors were accountable for. Importantly, even if (in continental Europe at least) the Commission recognised that the company law stricto sensu Footnote 101 has not ushered in ‘collective irresponsibility’ itself, it did not hold that the EU can ‘engineer back’ the neoliberal transformation of corporation through a change of discourse or soft law measures – as we have learned from past attempts.Footnote 102 Instead, it will need to be established which issues would need to be laid down in legislation,Footnote 103 announcing the return of legal strategies.

C. A push back against the ‘Thicker’ corporate-self

Of course, the shift in the imaginary of prosperity that the ‘sustainable corporate governance file’ represents was, like that of Milton Friedman in 1970, far from anything close to a social consensus. Immediately after publishing the inception impact assessment, which favoured a more serious intervention in corporate governance with hard company law rules,Footnote 104 a plethora of actors and voices came forward to challenge it. The industry, which had received relatively limited access to the Commission in the period of the preparation, entered a warpath. It mobilised all kinds of actors in support of its cause – including Member States and the Regulatory Scrutiny Board.Footnote 105 Several Nordic Member States, most notably Denmark (with its business associations very active on the issue), engaged in considerable ‘diplomacy’ with a view to cut back on the Commission’s ambitions.Footnote 106 In addition to this, many corporate governance and company law scholars organised events often critical of the proposals.Footnote 107

It is rather telling that the most consequential pushback against this shift in the imaginary of progress came, at least initially, from the Regulatory Scrutiny Board (the Commission’s ‘regulatory watchdog’). Despite what one may think, this is an organ established with a view to constraining the power of the government and, by extension, give more ‘lebensraum’ to (especially corporate) private actors.Footnote 108 Clearly, while ‘good regulation’ may have been a worthwhile objective, the Regulatory Scrutiny Board – set up by the Juncker’s Commission in 2015, with the USA OIRA (Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs) in mind – has its own particular way of ‘bettering’ regulation. Namely, both its methodologies (economic/cost benefit analysisFootnote 109) and composition (it is populated mainly by members who have economics and business administration backgrounds),Footnote 110 poise it to reproduce the dogmas and ideologies of the neoliberal consensus – long after many others have moved on. Unsurprisingly, industry focused its efforts there – ultimately gaining the access it wanted and discussing the substance of the Commission’s inception impact assessment with the Regulatory Scrutiny Board (in violation of its own rules).Footnote 111

In what follows, I will focus only on ‘formal’ challenges to the Proposal that came through official public channels – via the decisions of the Regulatory Scrutiny Board, as well as the submissions of different stakeholders to the consultation proceedings. This certainly does not cover all the possible avenues of criticism, but that is not decisive for the purposes I entertain here. I am rather interested in identifying important arguments made against the Proposal and the conception of the corporate self, economy, politics, government, nature and law upon which they stand.

The inception impact assessment, as well as the full impact assessment, were rejected twice by the Regulatory Scrutiny Board (RSB). In its first opinion, the RSB claimed that the Commission’s inception impact assessment set out ‘a very broad and intangible problem’, and it did too little to show the existence of that same problem, since it was not substantiated with clear evidence that EU businesses do not sufficiently address sustainability. Footnote 112 Yet, it was not an issue of the quantity of information provided by the Commission. Even the 97-page impact assessment, put together by the Commission knowing the stakes and trying to make their most substantiated case, did not as much as introduce an element of hesitation in the second opinion of the RSB, who claimed the

problem description remains vague and does not demonstrate the scale and likely evolution of the problems the initiative aims to tackle does not provide convincing evidence that EU businesses, in particular SMEs, do not already sufficiently reflect sustainability aspects or do not have sufficient incentives to do so.Footnote 113

In addition to this, two large influential groups of corporate law scholars, that is the group of Nordic professors (counting 27 people) and ECGI group of corporate governance scholars (counting 86 people), made public statements against the problem definition. In the elaborate position submitted to the consultation by the Nordic Professors, they suggested that the E&Y Study, and thus also the Commission’s inception impact assessment, exaggerates the problem of climate change and neglects the many other, equally serious, problems facing both company directors and EU legislators in their obligations to their respective constituencies.Footnote 114 They advised the Commission to place more trust in the efforts businesses are already making, insofar as the regulatory options recommended by the Study would seriously harm European business and prevent it from continuing to contribute to the sustainable growth and prosperity that the Union needs to fulfil its overall policies.Footnote 115

Those who were not convinced with the new imaginary of corporation will also see no value in using hard law as a means to bring about changes in corporate governance. On this note, the Nordic Professors suggested there was no need to change corporate law since the current conception captures all that is required: ‘Just as the company interest includes a multitude of stakeholders does the concept of directors’ duties comprise the same multitude and current company law needs not change to reflect this’.Footnote 116

The ESGI group, although more sympathetic to the environmental urgency, also did not share the enthusiasm for the company law reform, and rather suggested that the ‘regulation should instead focus on correcting market failure, through taxing externalities, curbing monopoly power and improving information disclosure’.Footnote 117 In truth, for those who have followed the discussion in this field, such statements may sound a bit like a broken record. Information provision, taxation and competition law – measures favoured in law and economics scholarship – have been shown as either ineffective (information provision),Footnote 118 impracticable in the context of globalisation (taxation),Footnote 119 or simply inapplicable to the issues of concern (competition law came to endorse monopoly power).Footnote 120

These same commentators also seem to remain content with private standardisation and soft-law approaches that typify the neoliberal imaginary of corporation. Hence, the Nordic professors reminded the Commission that it had adopted a position which

Openly conflicts with adopted policies of the Union in secondary legislation like the Shareholders’ Rights Directive amendment (SRD2), which as explained in the Commission’s 2012 Action Plan strives to continue the aim of the first SRD to encourage shareholder engagement and standing vis-a-vis management, notably to engage institutional investors in respect of voting and active commitment with management as part of a good stewardship effort.Footnote 121

The stress on ‘encourage’ rather than legally mandate was added by the writers of the response, the Nordic Professors themselves.

Perhaps the strongest pushback, however, was mounted against the Commission’s idea to introduce changes, paired with administrative and civil liability, regarding director’s duties. Placing a set of demanding duties and obligations on company directors seemed to go strongly against the intuition of many corporate (law) scholars. The group of Nordic professors wrote:

Strangely, the [Ernst and Young] Study appears to believe that directors as opposed to shareholders have an incentive to act in the long-term interest of the company and would do so if not restrained by shareholders [.. .]. rude experience that directors are in fact not long-term oriented, but motivated by short-time enrichment and if left unsupervised prone to divert company funds to their own pockets or use them for self-aggrandising projects like unnecessary investments and empire-building takeovers.Footnote 122

The ECGI group adds that placing more duties on the managers would lead to an even ‘bigger danger for stakeholder value [which] is not shareholder capitalism but “managerial capitalism”, where unaccountable managers shrink the pie for both shareholders and stakeholders.’Footnote 123

After many years of discussing how to align the agency of managers to that of shareholders, judged under a relatively simple metric of share price, this corporate governance constituency seems distrustful not only of the willingness, but also the capacity of corporate leaders to act responsibly. This infantilisation and/or demonisation of company directors is perhaps one of the most notable shifts that has taken place from the time Friedman wrote his famous Article. Friedman was in no way concerned that corporate executives were not able to take the interests of workers, the environment or inflationary pressures into account. Rather on the contrary, he thought they were all too able to – but that this amounted to not acting in the interest of their employersFootnote 124 and spending someone else’s money.Footnote 125

Today however, when the Commission proposes to introduce company directors’ obligations, it is either feared that managers are too self-interested to observe them or too difficult for directors to balance these contradictory interests.Footnote 126 Yet if directors so eagerly assumed the obligation to balance these very complex sets of interests in the past – much to the dismay of Friedman – why could not they do it today? All the more so given that their personal capacities must have grown multiple times – judging that they earn some 10 to 15 times more than their colleagues in the ’60s and ’70s. The obvious irony here is that the preoccupation of corporate scholarship with constraining the power of managers (so called ‘shareholder primacy’) has made managers considerably richer, increasing the pay gap between managers and workers more than tenfold over the past 40 years.Footnote 127 At the same time this has narrowed the set of concerns they need to care for and the group of actors to whom they are accountable.

D. A partial retreat from the ‘Sustainable corporate governance’

After two negative opinions of the RSB, internal pressure from other DGs and a strong lobbying by several Member States and their business associations, the Commission tamed its ambition to tackle a broader range of issues that may fall under ‘sustainable corporate governance’ and limited its proposal to issues linked with due diligence only:

This proposal regulates due diligence obligations of companies and at the same time covers – to the extent linked to due diligence – corporate directors’ duties and corporate management systems to implement due diligence and thus processes and measures for the protection of the interests of members and stakeholders of the company.Footnote 128

This retreat to due diligence, the approach compatible with the neoliberal corporation in its voluntary or soft-law forms for a couple of decades, seemed to bring the European Commission back to safety. International agreements on this issue go so far as to invite Member States (and by extension the EU) to act, and some MS (France, Germany, the Netherlands) have already started doing so, making the EU action necessary for internal market reasons.Footnote 129 But the broader corporate governance concerns regarding stakeholder involvement, regulation of director remuneration, business strategies that incorporate science-based sustainability standards, and serious civil liability for violation of sustainability standards have all but disappeared from the draft – at best serving as an invitation to the European Parliament and Council to discuss these issues.

And yet, the attempt of the Commission to introduce such a broad measure that aims to reconstitute the corporation around some sort of ‘social responsibility’, rather than a narrow focus on profit, is both symptomatic and co-constitutive of the emergent imaginary of prosperity. Crucially, this is more than just a shift in political ideology ‘to the left’. Only relatively recently, social democrats such as Blair or Schroder have empowered shareholders to bring about the better world, aided in this effort by the European Union (both the Court and the Commission).Footnote 130 Instead, today the European Commission (led by a conservative politician)Footnote 131 seems to suggest that our pursuit of prosperity thus far – through ‘shareholder value’ – has led to multiple crises, and that we may need to reconceptualise the corporation. This rethinking builds on a growing body of knowledge, corroborated by policy action at both the national and international level,Footnote 132 and is becoming a part of the new synthesis of collective prosperity.

At the same time, the opposition of the Regulatory Scrutiny Board is testament to the power of ‘institutionalising’ specific policy agendas – in this case, small government and deregulation – in bodies that are composed of and using methods proximate to the agenda pursued.Footnote 133 Bodies such as the RSB are likely to hold out the most against shifts in the imaginary of prosperity. Whilst they may be unable to hold back the tide entirely, they can certainly slow it down, as the RSB did in this case.

4. Toward a collective imaginary of corporation in the EU

A. Mounting contradictions: a shift in underlying knowledge

The new imaginary of prosperity is often preceded by the observation of problems and developments that usually (if not alwaysFootnote 134) translate into the production of academic knowledge aiming to systematise and provide answers to the problems uncovered. This has also been the case for the sustainable corporate governance file (as we learnt through the backdoor). Namely, many of the criticisms levelled at the Commission for its reassessment of the complex problem seemed to stem from the knowledge that grounded the Ernst&Young report, as well as the Commission and Parliament’s positions.

The Ernst&Young Study (serving as the basis for the Commission’s initial impact assessment, the Parliament’s recommendation, and the final proposal of the Directive) seems to draw primarily on green finance and corporate (law) scholarship regarding business and human rights on the one hand,Footnote 135 and the climate and environment on the other.Footnote 136 One would think that given the subject matter of the Directive the choice was an obvious one – with the Ernst&Young consultants recognising that. However, the considerable outcry in the wake of the inception impact report made clear that there was far more to the story.

Scholars who usually claim ownership of the field of ‘company law’ and ‘corporate governance’ are company law scholars, law and economics scholars and law and finance scholars. These fields are strongly male dominatedFootnote 137 and often include a large proportion of practicing corporate lawyers. Now, given that these fields have been dominated by research centred on the neoliberal imaginary of the corporation – shareholder primacy, shareholder activism, agency problems (at times with the ESG flavour)Footnote 138 – the knowledge they produced failed to provide an obvious source of insight that a consultancy firm such as Ernst&Young would look to when trying to identify the ‘root causes’ of corporate short-termism.Footnote 139

The omission of this ‘mainstream knowledge’ precipitated in an offence, best illustrated by the group of Nordic company law scholars who, when responding to the Commission’s (and Ernst and Young’s) claim that the position the report presents is the consensual position in the field of corporate law and sustainability, say: ‘In legal discourse, silence is not acquiescence, but more likely reflects genuine disinterest.’ Footnote 140 By implication, these company lawyers admit that they were neither interested in the topics that were taken as relevant by E&Y (climate or human rights), nor were they bothering to engage with scholars dealing with these matters.

However, whilst the owners of the corporate governance field remained concerned with perfecting the alignment between shareholders’ and managers’ interests, something shifted, much to their surprise. When the European Commission came to explore how corporate law and governance relate to some of the problems it increasingly identified – from the perspective of sustainability (as articulated by natural and social sciences) and inequality (as articulated by an ever growing body of economic, social and legal sciences) – the types of scholarship produced by the aforementioned corporate law groups appeared irrelevant.Footnote 141 In a world, where corporations produce 50 per cent of CO2 emissions and inequality has become rampant (much to the advantage of large shareholders and managers), the ongoing concern with aligning the interests of managers and shareholders may seem somewhat redundant.

Fortunately for this group of scholars, they still found a sympathetic ear in the Regulatory Scrutiny Board, which also based its extraordinary double rejection on the fact that the

report should be revised to present the evidence in a more balanced and neutral way.’Footnote 142 Or that ‘the report should present more systematically the views of different stakeholder categories. It should find a better balance between supportive and critical views expressed.Footnote 143

While the latter is likely more concerned with business interests,Footnote 144 the neglected corporate law scholars (working around a different paradigm of the corporation) may have strengthened the RSB’s position.

The famous philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn argued decades ago that it is the accumulation of anomalies and contradictions that will drive ‘normal science’ – such as that of mainstream corporate (law) scholarship today – out of its dominant position.Footnote 145 The inability of traditional corporate governance scholarship to provide answers to the problems plaguing the corporate world left these fields, and by extension the RBS, with only the option of interpreting any problems away.

This side-lining of the more traditional corporate governance scholarship has to be seen against the backdrop of a shift towards ‘interdisciplinarity’ in science more generally, which sees most established scientific disciplines as increasingly failing to provide the answers to the many socio-ecological problems we face.Footnote 146 The case of company law expertise in ‘sustainable corporate governance’ seems to be no exception.Footnote 147 Quite tellingly, Ernst&Young (a consultancy with limited stakes and sensibilities as to which academic community may enjoy the ‘privilege’ of the mainstream) reached for literature relevant to the issues it was examining. The fact that neither the Nordic Professors nor the ECGI group occupied this space should be a cause for pause and self-reflection rather than offense.

B. Collectivising the corporation in the EU: first steps

On several occasions I have alluded to the fact that the ‘sustainable corporate governance’ and CSDD Proposal operate from a different imaginary of prosperity than the neoliberal one. I have also alluded to the fact that this is more than just a shift in political ideology in any narrow sense. What we are seeing is the emergence of a new synthesis of how our economy, law, politics or nature work together, and how we can get to a better (or at least liveable) future. This synthesis introduces more public and collective control over corporate activity – shifting the responsibility for progress and prosperity from private to public institutions. The CSDD aims to do so by requiring social responsibility of corporations, using law as a means to deliver it, and designating stakeholders and society as those to whom the accountability is owed. Such a development is not too remote from what irritated Milton Friedman in his 1970 Article:

the doctrine of “social responsibility” taken seriously would (.. .) not differ in philosophy from the most explicitly collective doctrine. It differs only by professing to believe that collectivist ends can be attained without collectivist means.Footnote 148

Critical participants in the public consultations have not missed that the ‘sustainable corporate governance’ file starts from a very different imaginary of prosperity. Thus, Nordic professors present us with a more contemporary (and somewhat cruder in comparison with Friedman) critique of the Commission’s synthesis:

We are surprised of the apparent hostility to shareholders as a group and the idea that to serve shareholders’ interest is to increase inequality and somehow unfairly benefit the ultra-rich ‘1 per cent’. It is sentiments that we mostly associate with anti-market ideologies that are difficult to reconcile with the framework of a free market economy, private ownership rights and innovation and progress through competition upon which the European Union is based.Footnote 149

This ‘framework’ they allude to is premised on a synthesis that places the ‘free market economy’, ‘private property’ and ‘competition’ as the drivers of ‘innovation’ and ‘progress’. It represents (in short) the imaginary of privatised (neoliberal) prosperity that has been ushered in since the 80s and made hegemonic across the political spectrum and society in the ’90s. In contrast, expanding the interests and purposes of the corporation through ‘corporate social responsibility’ presents an imaginary of prosperity resting on a very different relationship between public and private, political and economic, individual and collective. At the time of Milton Friedman, the ‘collectivist’ imaginary had been embraced both by the ‘captains of industry’ as well as governments – also suggesting that this imaginary, like neoliberal one, transcended the entire political spectrum.Footnote 150

I still owe to the reader a more poignant elaboration of the reasons on which we base the conclusion that the European Commission is making, if timidly, a shift to a new social imaginary of collective prosperity. Before I do so, I need to shortly lay out the set of interventions that the Proposal aims to make, including some of its limitations, and with reference to the specific articles of the Directive where possible.

The CSDD Proposal aims to expand the gaze of the company – that is large companies (Article 2,3), including extra large non-EU based companies (Article 2) – and its directors beyond profit, to HR and environmental impacts (Article 3, and annex 1), across their supply chains, but limited to ‘established business relations’ (Article 3).Footnote 151 Large companies will be required to put in place due diligence measures to prevent, mitigate, end or minimise eventual abuses (Article 4 – 10) in their operations, including among their established business relations. However, companies can avoid civil liability for abuses even by their ‘established business relations’ where they have been given contractual assurances as verified by an auditing firm (Article 22).

When it comes to climate obligations, the largest companies are required to produce plans to ensure that their business models and strategies are compatible with the transition and the Paris agreement (Article 15), and those for whom the climate is a principal risk are required to adopt emissions reduction plan (Article 15). Importantly, in parallel to the rather traditional system of civil liability (Article 22), the Proposal introduces in a novel move an administrative system of liability (Article 17–20), including a network of European Supervisory authorities (Article 21). Finally, there are also a few remaining references to directors’ duties, whose remuneration should be co-related to performance on the climate and environmental front (Article 15), and whose duties should be clearly specified as comprising the responsibility for due diligence and transition plans (Article 25).

What, if anything, among these relatively unambitious interventions suggests that we are seeing a more serious shift in the imaginary of prosperity? Obviously, such a shift cannot be superficial. Rather, it would require a shift at the level of ontology, epistemology and ethics to transform the political economy in such a way to dethrone markets and private actors from the driver’s seat of progress.

Despite the relatively limited nature of the Proposal, many important departures in this direction have taken place. To start, and in rather stark contrast to the assessment of the Regulatory Scrutiny Board, the European Commission and European Parliament argue that the problems economies and societies are facing today – social and environmental – cannot be solved by the market. Instead, politics and government have a major role in shaping the economy.

Law, in this Proposal, is not seen as ‘lagging behind’ technology or business. Rather, it is seen as constitutive of private actors, social and economic relations as well as economy at large, and thus also capable of re-shaping it. The room for manoeuvre that company law leaves today for private parties to fill – for instance with regard to norms of shareholder value – should be filled by public law norms in order to steer the actors away from destructive pursuits. Soft law, which has been so popular in the neoliberal imaginary of progress, is out of the picture – not only did it not work (like in the case of the Non-financial reporting directive),Footnote 152 but it also seems to make less sense to leave the questions of collective good entirely to the decisions of private actors.

What fundamentally distinguishes the new imaginary of collective prosperity from the neoliberal imaginary of prosperity and the post WWII imaginary of collective prosperity, is the rearticulation of the relationship between nature and society. If the neoliberal imaginary of prosperity saw neither nature (at all) or society (viewing it only as a collection of individuals), and the post WWII imaginary of collective prosperity mainly linked questions of nature to that of precaution,Footnote 153 ‘sustainable corporate governance’ (as inspired by the European Green Deal) aims to reshape the society in a much more nature-centric way. It is thus no surprise that ‘sustainable corporate governance’ aimed to place ‘sustainable value creation’ at the centre,Footnote 154 with the Commission’s initial plan also including stronger directors’ duties of care and a requirement to develop a sustainable corporation reinforced with science-based targets. The final trimming down of the ambition, prompted by commentary that climate and nature played too dominant a role,Footnote 155 only underscores this point.

When it comes to the conception of the ‘corporate-self’, the set of concerns, interests and duties that the corporation embraces is hereby expanded via legal intervention beyond the narrow, profit-driven neoliberal corporate self. Companies in this new imaginary are certainly not there to further ‘shareholder value’ alone and shareholders themselves are not seen as the only, or the best, ‘accountability mechanism’ for the corporation. Instead, it is clear to lawmakers that the ethics of corporate conduct need to change. Again, it is responsible directors that Friedman so abhorred, and current corporate scholar’s mistrust, that need to be committed by hard law to social responsibility, as currently both their socialisationFootnote 156 as well as their financial incentivesFootnote 157 work against responsible conduct. The new rules will aim to expand the gaze of directors toward all stakeholders as well as the bigger chunk of the supply chain.

Profit (which has come to mean ‘shareholder value’), cherished first by Friedman and later by much corporate law scholarship for its relative ‘clarity’Footnote 158 and ‘precision’ in directing directors’ action,Footnote 159 cannot be the main guiding star for managerial conduct any further. If anything, the shareholder perspective must be paired with ‘stakeholder’ perspectives,Footnote 160 which in turn need to account for our interdependence with nature – a complex ecosystem that cannot be controlled, but instead approached with seriousness and care.

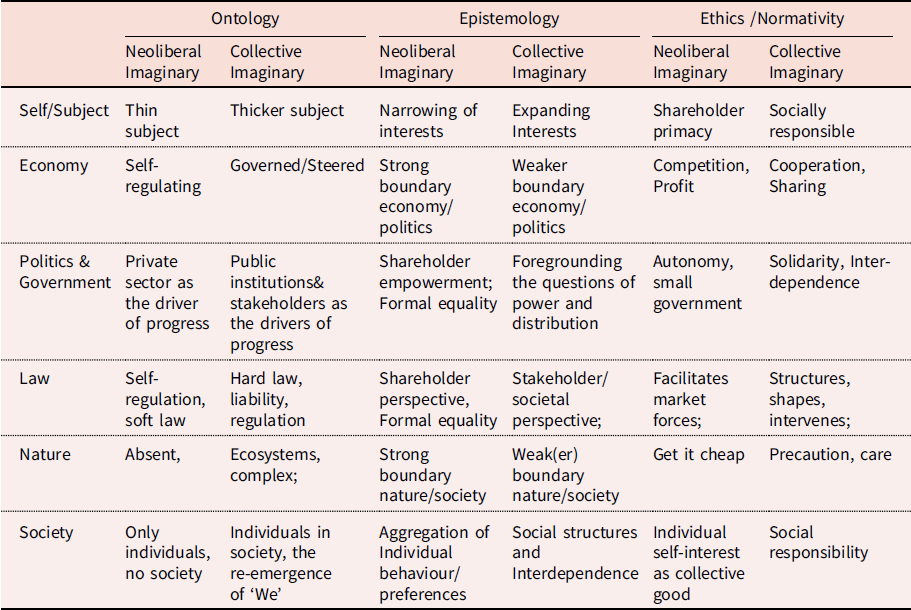

Finally, the exasperation of EU institutions with waiting for voluntary action by corporations has also led to a shift in enforcement strategies. Thus, in this Proposal we see the growing role of the public via administrative enforcement which, next to the courts, must ensure that companies are socially responsible. And while civil liability has been trimmed down due to pressures exerted upon the Proposal, administrative liability has remained mostly untouched Table 1.

Table 1. The shifts in the imaginary of corporation, taking place at the background of the ProposalFootnote 161

Of course, the Proposal currently tabled is somewhat less ambitious than the set of ideas put forward by the Commission in its inception impact assessment. What we see here is certainly nowhere close to a more confident imaginary of collective prosperity. To be more specific, the due diligence obligations remain limited only to very large firms – in the most recent proposal, only some 13,000 firms would be required to abide by due diligence principles. Footnote 162 Also, greater responsibilities only attach to firms with an ‘established relation’ to a supplier – a limitation that threatens to weaken the whole proposal according to the NGOs, while departing from established international principles such as the OECD guidelines.Footnote 163 The participation of and responsibility towards non-shareholders is also not supported via strong obligations – be it the obligatory forms of stakeholder engagement, civil liability, liability of directors, obligatory science-based targets in the company or a clear link between remuneration and performance on ‘non-financial’ front. More generally, the current proposal also fails to rethink the issues of power or profit in a more substantial sense. But none of this renders the Proposal any less important, for it makes clear that an identifiable shift on most core aspects of the social order is underway.

C. Collectivising the corporation in the EU continued: taking the question of power and profit seriously

Whereas the Proposal may present sufficient indicators that the imaginary of prosperity is shifting, some of the more crucial questions that a more collective imaginary would hope to tackle – that of private power and the privatisation of profit – is left for another day. If it were not for a soft reference to linking directors’ remuneration to the performance on ‘non-financial’ front, the distributive questions would stay mostly outside of the Proposal’s purview. And yet, it is exactly those questions that would be central to addressing the challenges of both social and environmental unsustainability that the Proposal sets out to tackle.

The question of power

Even if the Proposal is directed primarily at global supply or value chains – themselves as much contractual as corporate creatures – the approach of the Directive remains auspiciously uninterested in the (mostly contractual) questions of (bargaining) power, contractual conditions and the distribution of value in global value chains.Footnote 164 This is particularly surprising since the problem of power in value chains has been on the EU’s radar for quite some time – showing that a ‘politically acceptable’ type of intervention was not hard to come by.

In 2019, the European Union enacted an ‘Unfair Trading Practice Directive’ (UTPD) that aims to introduce a minimum standard of protection against unfair trading practices in intra-EU agricultural supply chains. The EU did so because

larger and more powerful trading partners seek to impose certain practices or contractual arrangements which are to their advantage in relation to a sales transaction. Such practices may, for example: grossly deviate from good commercial conduct, be contrary to good faith and fair dealing and be unilaterally imposed by one trading partner on the other; impose an unjustified and disproportionate transfer of economic risk from one trading partner to another; or impose a significant imbalance of rights and obligations on one trading partner.Footnote 165 (rec1).

The UTPD Directive then goes on to prohibit a number of contractual terms and practices as ‘unfair trading practices’ – including pricing, delivery terms, cancellations, changes of orders etc – expanding ‘unfair terms protection’ taken from consumer contracts to another group of weaker parties: downstream suppliers in supply chains.Footnote 166

The UTPD presents an important break from what can be seen as the unwillingness of the EU to deal with the imbalance of power and misuse of bargaining power in business to business (B2B) relations.Footnote 167 Even though this is not without criticism, we can see this Directive as an important shift towards a more collective imaginary of prosperity in the context of an economy that is strongly reliant on supply chains. On its own terms, the UTPD departs from several cornerstones of the neoliberal imaginary of economy, government, and law. First, the concern and governmental engagement with economic structures and relations – ie the dynamics between big/small actors with differing levels of power and influence – presents a shift in economic imaginary in so far as we no longer (as we did in the previous decades) trust the market to deal with this problem. Second, we also observe a shift in the role of government, which has power over and is responsible for the existing economic structures in the economy and thus turns to hard law to re-shape these economic relations. Third, in terms of the legal imaginary, the reliance on hard law as well as the turn away from the principle of formal equality, justified by the actually occurring injustices in the market, are an important shift from the neoliberal imaginary.

Clearly, similar abuses of stronger bargaining positions such as those that happen in intra-EU agricultural chains also happen elsewhere – and likely on an even greater scale. Global textile supply chains, electronics supply chains, mineral supply chains, etc have all played host to some of the most egregious human rights, labour and environmental violations.Footnote 168 In these often ‘captive’ supply chains,Footnote 169lead firms can exercise disproportionate amounts of power, shifting contractual risks and costs on suppliers upstream, while keeping most of the benefits.Footnote 170 Companies in superior bargaining positions can, for instance, control the timing of payments and deliveries, reserve the right to cancel orders, change quantities, times or specification of goods to be delivered and, of course, pressure for the lowest possible prices. For many powerful multinationals, such as Apple, it is the enormous flexibility of suppliers in developing countries that is the greatest attraction.Footnote 171 Of course, such flexibility comes at a price. It is these various ‘trading practices’ that contribute directly or indirectly to all kinds of HR and environmental violations by making it very difficult to create material conditions upstream for the fair treatment of workers and environmental protection.

Yet these (often) contractual aspects of the corporation remain auspiciously non-addressed by the CSDD Proposal.Footnote 172 Paradoxically, to the extent that some contractual provisions are included in the Proposal, they are there to enable the shift of costs and risks upstream. Article 7 and 8 of the Proposal indicate that companies can fulfil their due diligence obligations by obtaining ‘contractual assurances from a direct partner’ (7/2/c, and 8/3/c), provided that when

contractual assurances are obtained from, or a contract is entered into, with an SME, the terms used shall be fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory. The contractual assurances or the contract shall be accompanied by the appropriate measures to verify compliance. (7/4, 8/5).

While it is commendable that the CSDD Proposal refers to fairness and non-discrimination in these clauses, this reference only applies to contractual assurance clauses. It is only these clauses that aim to shift due diligence obligations upstream that must be fair. Yet, as the previous discussion has hopefully made clear, there are more things that can go wrong in contracts with suppliers in supply chains. What about clauses concerning price/value, changes, terminations, cancellations, timings, carriage of risk etc, which are the core means of distributing ‘unfairness’ through chains of contracts? The CSDD is also not clear as to who should pay for the obligations that come with the due diligence rules, including the ‘measures to verify compliance’. There is nothing to suggest that the costs of assurances, that is, the costs related to observance of standards including the ‘measures to verify compliance’ (ie auditing), will not be passed down the chain without compensation. While the fairness provisions perhaps aim to counter this, they are not specific enough to guarantee this outcome.

Omitting the question of power may be a consequence of staying within the framework of corporate governance. With its belief that one can deal with economic problems by focusing on the internal governance of the company,Footnote 173 corporate governance has little to say about the ‘fundamentals’ of organising production in value chains. The subsequent narrowing down the Proposal to ‘corporate due diligence’ only, as the result of the RSB’s intervention, has only made this limitation more obvious.Footnote 174

The question of profit

The other ‘elephant in the room’ when it comes to the CSDD Proposal concerns the privatisation of profit. Today the benefits of social cooperation accrue to the lucky few – either because of their geographical location, age or their ‘social status’ – while the costs of cooperation are distributed broadly. This is particularly well demonstrated in the context of global supply and value chains, where the benefits end up (for the most part) with the managers and shareholders in the Global North, whilst the costs are broadly distributed and particularly impactful in the Global South. And yet, beyond a very timid reference that the directors’ remuneration should also reward their performance on the due diligence front – one that the Council wants to see disappearFootnote 175 – the question of what should we do with the (distribution) of profits is not touched by the Proposal.

This need not be the case. Possible inspiration for how to start rethinking the issue of profit can be found in existing initiatives at the EU level. The EU’s 2021 Action plan for the Social economy,Footnote 176 which builds on the initiative of DG Enterprise from the first half of 2010s on Social innovationFootnote 177and Social business initiative,Footnote 178 put forth a very different understanding of the enterprise and business activity. These initiatives were developed in the wake of 2008 crisis, insofar as it provided ample evidence that it was social or solidary enterprises that were fundamental to ensuring social provision and the resilience of communities and societies during the economic downturn, especially in the South of Europe.Footnote 179

Central to the earlier initiative of DG Enterprise was the concept of ‘social enterprise’, which was defined as follows:

Those for whom the social or societal objective of the common good is the reason for the commercial activity, often in the form of a high level of social innovation.

Those whose profits are mainly reinvested to achieve this social objective.

Those where the method of organisation or the ownership system reflects the enterprise’s mission, using democratic or participatory principles or focusing on social justice.Footnote 180

The conceptualisation of the enterprise along those lines resonates with the elements that remain at best embryonic in the CSDD Directive. First, not only that business should also be socially responsible, social responsibility could be actually at the heart of business. Social enterprises are not here to advance private interests, but to achieve common, that is collective or public, good. Second, profits, the generation of which is the landmark of the neoliberal imaginary of corporation, are not privatised in these social enterprises. Instead, they are ‘mainly reinvested’ to further the common good. In fact, there is nothing in the conception of business that forces people to direct their energies to business activity only if they can scoop large profits. Rather, there seems to be lots of economic activity that does just the opposite.Footnote 181 Third, such social enterprises are (often) organised in a more solid, non-hierarchical manner at the level of their fundamentals, drawing our attention to the central link between the ownership of capital and the new mechanisms of non-hierarchical business organisations.Footnote 182 Fourth, innovation is not only a result of the profit motive. Social enterprises explore new ways of social organisation (of production), innovating how we organise the economy and deliver the common good.Footnote 183

Unfortunately, this early initiative of DG Enterprise seems to have faded away after a couple of years, without any clear outcomes in terms of legislative proposals or measures. However, more recently it was DG Employment and Social Affairs that has picked up the policy action in this field, within the ‘Action Plan on Social Economy’.Footnote 184 In this Social Economy Action plan, the European Commission broadens the scope of activities included within the social economy to include all kinds of economic initiatives that share the following main principles and features:

the primacy of people as well as social and/or environmental purpose over profit, the reinvestment of most of the profits and surpluses to carry out activities in the interest of members/users (‘collective interest’) or society at large (‘general interest’) and democratic and/or participatory governance.Footnote 185

The Commission maintains that when it comes to profit, most – but not necessarily all – of it should be reinvested internally, or in the common good/social purposes pursued. The underlying expectation is that in an economy with a lesser pressure on profit making, not only will the distribution of gains from social cooperation improve (for instance making it more attractive to invest into workers or clean technologies), but it should also more generally produce less extractive businesses, since reinvestment and regeneration become the main orientation.Footnote 186

While the Commission has been concerned with the question of how to foster such regenerative economic activity by creating an ‘enabling environment’Footnote 187 for social economy enterprises to flourish, there is another possible direction that can be taken: namely bringing ‘mainstream economy’ closer to the social one. The European Commission itself notices the potential for ‘cross-fertilisation’ between social economy and mainstream economy: