Depression is a leading cause of disability worldwide, and improving its treatment is a global health priority.1 A third of patients do not achieve remission with current treatment approaches, which has a significant effect on occupational and social functioning.Reference Rush, Warden, Wisniewski, Fava, Trivedi and Gaynes2 First-line antidepressants also have limited efficacy in treating some symptom clusters, such as cognitive impairment.Reference Shilyansky, Williams, Gyurak, Harris, Usherwood and Etkin3 Within this context, there is a pressing need for novel antidepressant targets.Reference Marwaha, Palmer, Suppes, Cons, Young and Upthegrove4 However, drug discovery in psychiatry is notoriously challenging, with fewer than half of the new drugs approved by the USA Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the past 5 years in neurology.Reference Mullard5 One promising strategy is the repurposing of drugs known to act on receptors in the central nervous system and used to treat conditions affecting other organ systems.Reference Pushpakom, Iorio, Eyers, Escott, Hopper and Wells6

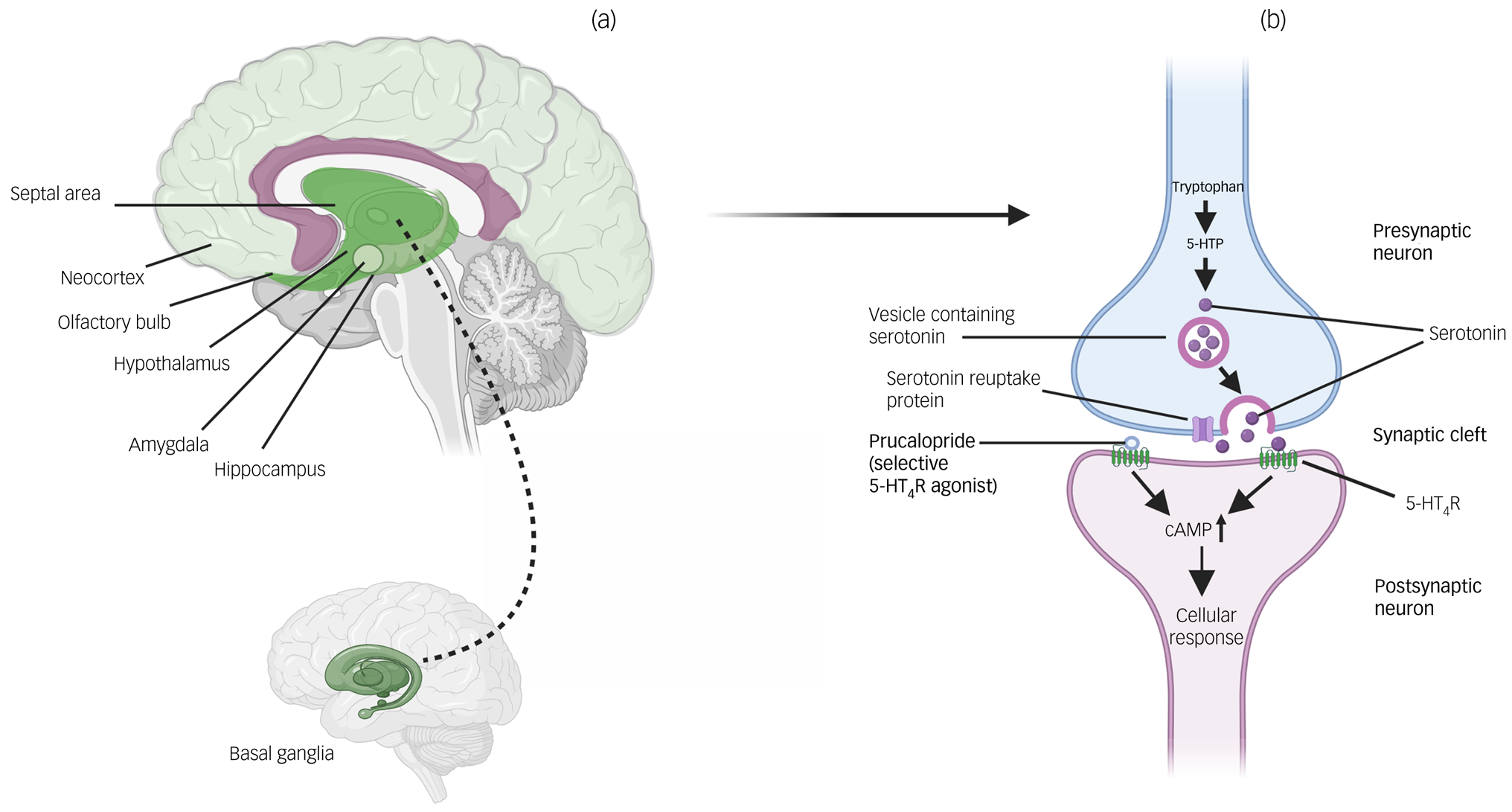

A first step in drug repurposing is the identification of a candidate compound. Serotonin 4 postsynaptic receptors (5-HT4Rs) are widely expressed in the brain, particularly in regions and networks related to mood and cognitive functioning (see Fig. 1).Reference Beliveau, Ganz, Feng, Ozenne, Højgaard and Fisher7 5-HT4R agonists have rapid antidepressant-like effects in animal models of depression,Reference Lucas, Rymar, Du, Mnie-Filali, Bisgaard and Manta8,Reference Mendez-David, David, Darcet, Wu, Kerdine-Romer and Gardier9 and a facilitatory effect on behavioural tasks of learning and memory in rodents.Reference King, Marsden and Fone10 In humans, there is also emerging experimental evidence to support a role for the 5-HT4R in depression and cognition.Reference Köhler-Forsberg, Dam, Ozenne, Sankar, Beliveau and Landman11,Reference de Cates, Wright, Martens, Gibson, Turkmen and Cowen12 Brain 5-HT4R binding is reduced in patients with depression compared with healthy controls, and associated with deficits in memory performance.Reference Köhler-Forsberg, Dam, Ozenne, Sankar, Beliveau and Landman11 However, clinical evidence for the effect of 5-HT4R agonists on depression is lacking. Emulated target trials allow assessment of the effect of a treatment on a clinical outcome outside of the existing license, using observational data.Reference Hernán, Wang and Leaf13 Using this approach, we assessed whether exposure to the 5-HT4R agonist prucalopride (an anti-constipation agent acting on 5-HT4R in the gut, but also with good brain penetrationReference Tack, Derakhchan, Gabriel, Spalding, Terreri and Youssef14) is associated with a lower risk of depression within 1 year since first prescription, compared with two alternative anti-constipation agents that have no known effect on 5-HT4Rs or the central nervous system. We hypothesised that participants on prucalopride would show a lower risk of depression within 1 year.

Fig. 1 Locations of 5-HT4Rs in the brain and actions of prucalopride. (a) Brain regions where 5-HT4Rs are particularly highly expressed (see Beliveau et alReference Beliveau, Ganz, Feng, Ozenne, Højgaard and Fisher7). Darker shading indicates regions of highest expression (i.e. basal ganglia); lighter shading indicates relatively lower expression (i.e. neocortex). (b) Action of prucalopride at a serotonin synapse as a highly selective agonist at transmembrane G-protein-coupled 5-HT4Rs. 5-HT4R, serotonin 4 receptor; 5-HTP, 5-hydroxytryptophan; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate.

Method

Study design and data collection

The TriNetX USA Collaborative Network was used for this study, which is a network of anonymised electronic health records data from 60 healthcare organisations in the USA.Reference Taquet, Luciano, Geddes and Harrison15 In brief, this network allows access to over 100 million patients, with data including demographics, diagnoses and ICD-10 codes, medications, procedures, measurements (e.g. blood pressure, body mass index) and healthcare visits (see Supplementary Methods 1 available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2024.97 for details). Data is included from both primary and specialist healthcare organisations, and involves both patients insured and not insured under the standard USA system. Each healthcare organisation remains anonymous within TriNetX, and is able to provide data with the necessary consents and approvals as long as research is the sole use. The process of data de-identification is attested by a qualified expert as defined in Section 164.514(b)1 of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) Privacy Rule.Reference Taquet, Dercon, Luciano, Geddes, Husain and Harrison16 No further ethical approval is needed. As we used anonymised routinely collected data, no participant consent was required. We followed the approach of Hernán and Robins to emulate a target trial using electronic health records from TriNetX.Reference Hernán, Wang and Leaf13 The different components of the target and emulated trials are summarised below and detailed in the Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table 1. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines (see Supplementary Materials).

Participants and exposure

The primary cohort included individuals with a first prescription of prucalopride before the start date of analysis (25 January 2024). Two comparator cohorts were defined as individuals with a first prescription of linaclotide (a guanylate cyclase 2C agonist) or lubiprostone (a chloride channel activator) before 25 January 2024. For all cohorts, no age or gender restriction was applied, but patients with pre-existing diagnoses of common and/or serious mental illness were excluded (ICD-10 codes for psychotic disorders (F20–F29), mood disorders (F30–F39), anxiety disorders (F40–F48) and mental disorders due to known physiological conditions including cognitive disorders (F01-F09)). Patients were censored at their last clinical encounter or when they died. An intention-to-treat analysis was emulated by including all individuals who received one prescription of the drug in the corresponding cohort. See Supplementary Methods 2 for details on cohort definition.

All three medications (prucalopride, linaclotide and lubiprostone) are approved by the FDA for use in the USA for chronic constipation, are third-line pharmacotherapy options (i.e. when laxatives alone are insufficient) in national guidelinesReference Chang, Chey, Imdad, Almario, Bharucha and Diem17 and are available under Medicaid/Medicare.

Covariates

Cohorts were matched with propensity score matching for 121 variables capturing sociodemographic factors, and concurrent or history of comorbidities and medications that could be associated with differences in choices of anti-constipation treatment and/or with psychiatric disorders. These covariates were selected based on expert opinion as well as statistical differences between cohorts before matching (see Supplementary Methods 3 for details and Supplementary Table 2). Baseline characteristics of cohorts before matching (lifetime, 5 years and 1 year before inclusion) were checked (Supplementary Tables 3–5).

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the incidence of a first diagnosis of major depressive disorder (F32) within 1 year of the index date. Secondary outcomes included incidence of a first diagnosis of six other common and/or serious neuropsychiatric disorders in the first year: (a) mood (affective) disorder (F30–F39), as an overarching outcome, as well as (b) bipolar disorder (F31) specifically; (c) anxiety disorder (F40–F48); (d) dementia (any of F01–F03, G30, G31.0, G31.2 or G31.83); (e) substance use disorder (F10–F19) and (f) psychotic disorder (F20–F29).

Secondary analyses

Details on all secondary analyses can be found in Supplementary Methods 5.

Robustness analyses

Robustness of the results to changes in outcome, cohort and model specifications was tested under the following conditions: (a) excluding individuals with a contraindication for any of the study medications from all cohorts; (b) excluding those within the comparator (linaclotide/lubiprostone) cohort who had a prescription of prucalopride in the year before the index date, thus making cohorts mutually exclusive; (c) excluding those with a recorded prescription of the alternate drug in the 1 year following the index date from each cohort; (d) excluding those with additional pre-existing neuropsychiatric disorders and (e) excluding patients with a recent prescription of either of the two most common selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants (escitalopram and sertraline).

Negative control outcomes

To assess for potential unmeasured confounding, matched cohorts were compared in terms of a range of negative control outcomes that are not expected to be influenced by differences in anti-constipation medications.Reference Ali, Prieto-Alhambra, Lopes, Ramos, Bispo and Ichihara18 Twenty negative control outcomes were selected, adapted from previous analyses using the TriNetX database,Reference Colbourne and Harrison19 and first occurrences analysed both individually and as a composite outcome. A full list of negative control outcomes is available in the Supplementary Methods.

Additional comparisons

Influences of medication costs and Medicaid/Medicare availability were tested by using additional comparisons (in terms of psychiatric and negative control outcomes): (a) linaclotide (similar price as prucalopride) versus lubiprostone (cheaper than prucalopride) and (b) plecanatide (same mechanism of action as linaclotide and available under Medicaid/Medicare at the same time as prucalopride) versus linaclotide (available under Medicaid/Medicare earlier than prucalopride).

To assess whether differences in incidence of depression could be explained by differences in efficacy of anti-constipation drugs, we compared prucalopride with both comparator drugs in terms of incidence of an enema (taken to be an indicator of suboptimal anti-constipation treatment) over the 1-year follow-up period.

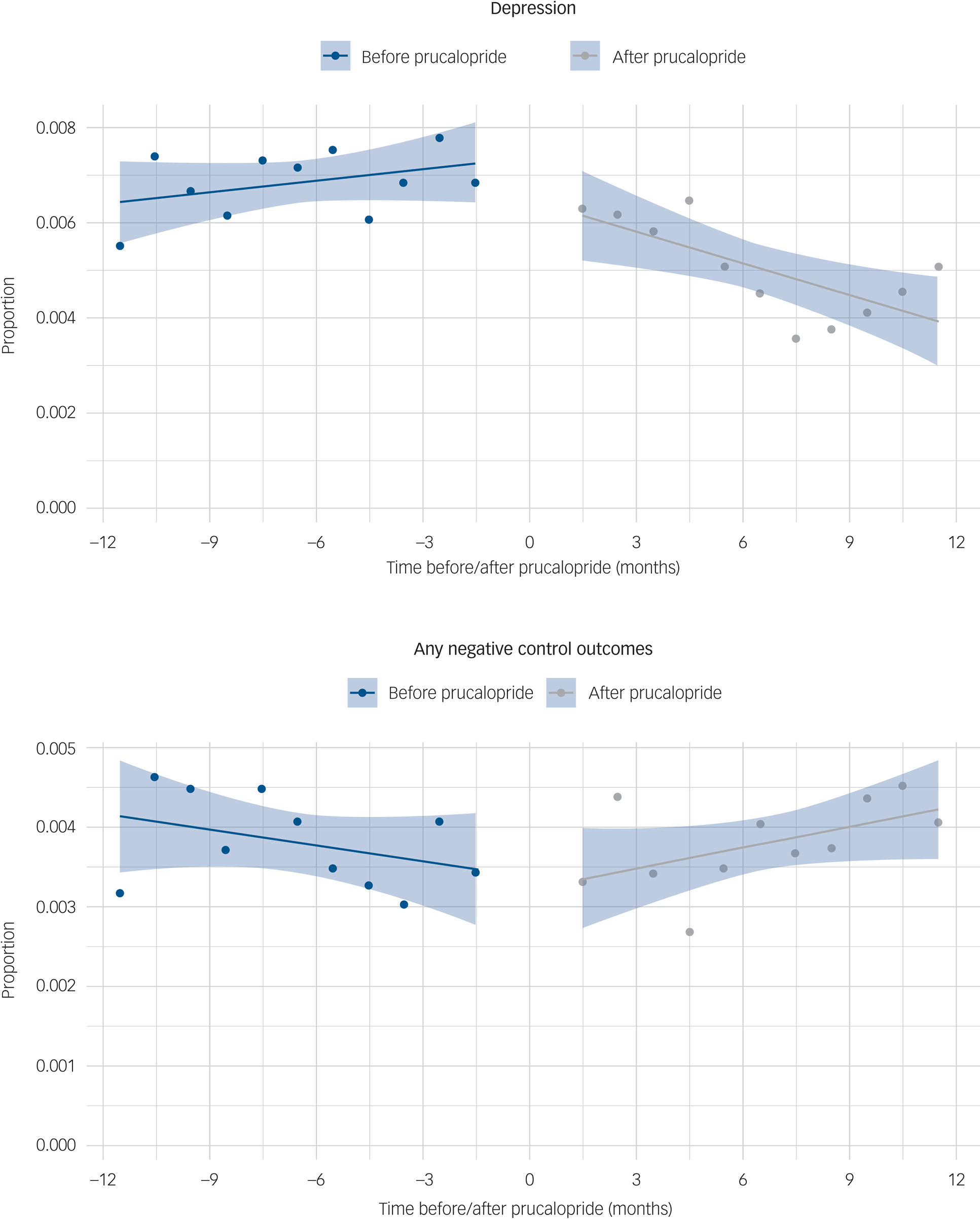

Interrupted time-series analysis

We complemented the emulated target trial with an interrupted time-series analysis comparing the trend in depression incidence in the 12 months after versus before the first prescription of prucalopride, and relative to the total number of people who had at least one health encounter within each month. We hypothesised a change in slope, with a progressive reduction in the number of depression diagnoses after initiation of prucalopride. This analysis was also conducted for negative control outcomes.

Statistical analysis

Propensity score 1:1 matching was achieved with a greedy nearest neighbour algorithm with a calliper distance of 0.1. Matching for a covariate was considered adequate if the standardised mean difference between matched cohorts was <0.1.Reference Taquet, Luciano, Geddes and Harrison15 Cumulative incidences over the 1-year follow-up period were estimated with the Kaplan–Meier estimator. The log-rank test was used to compare survival between matched cohorts and the Cox proportional hazard model was used to estimate hazard ratios with 95% confidence intervals (using the ‘survival’ package in R, version 4.2.1 for Windows; https://www.r-project.org/). The proportional hazard assumption was tested with the generalised Schoenfeld approach. E-values were calculated for all comparisons in the primary analysis. Reference VanderWeele and Ding20 Statistical significance was set at a two-sided P < 0.05.

Results

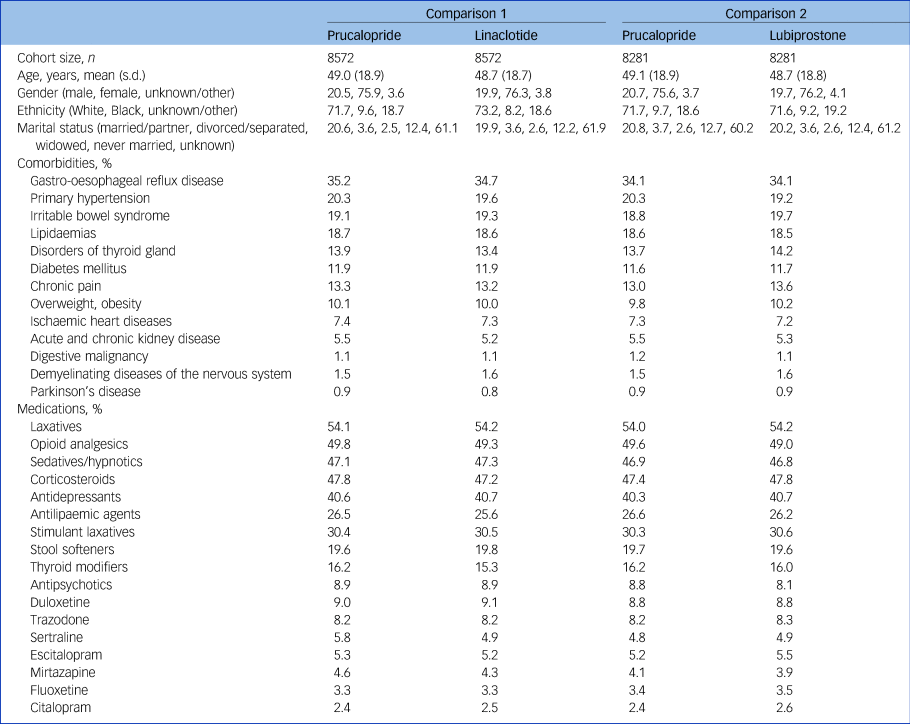

A total of 8694 patients had at least one prescription of prucalopride (mean age 48.8, s.d. 19.0, 75.8% female, 20.6% male), of which 8572 and 8281 were successfully matched 1:1 to patients with a first prescription of linaclotide or lubiprostone, respectively (see Table 1 for baseline characteristics of matched cohorts and Supplementary Tables 3–5 for baseline characteristics before matching).

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of matched cohorts of patients receiving prucalopride versus linaclotide (left columns) or prucalopride versus lubiprostone (right columns)

Lifetime prevalences are given as percentages. Baseline characteristics with a prevalence of at least 5% were included. All characteristics used for matching can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

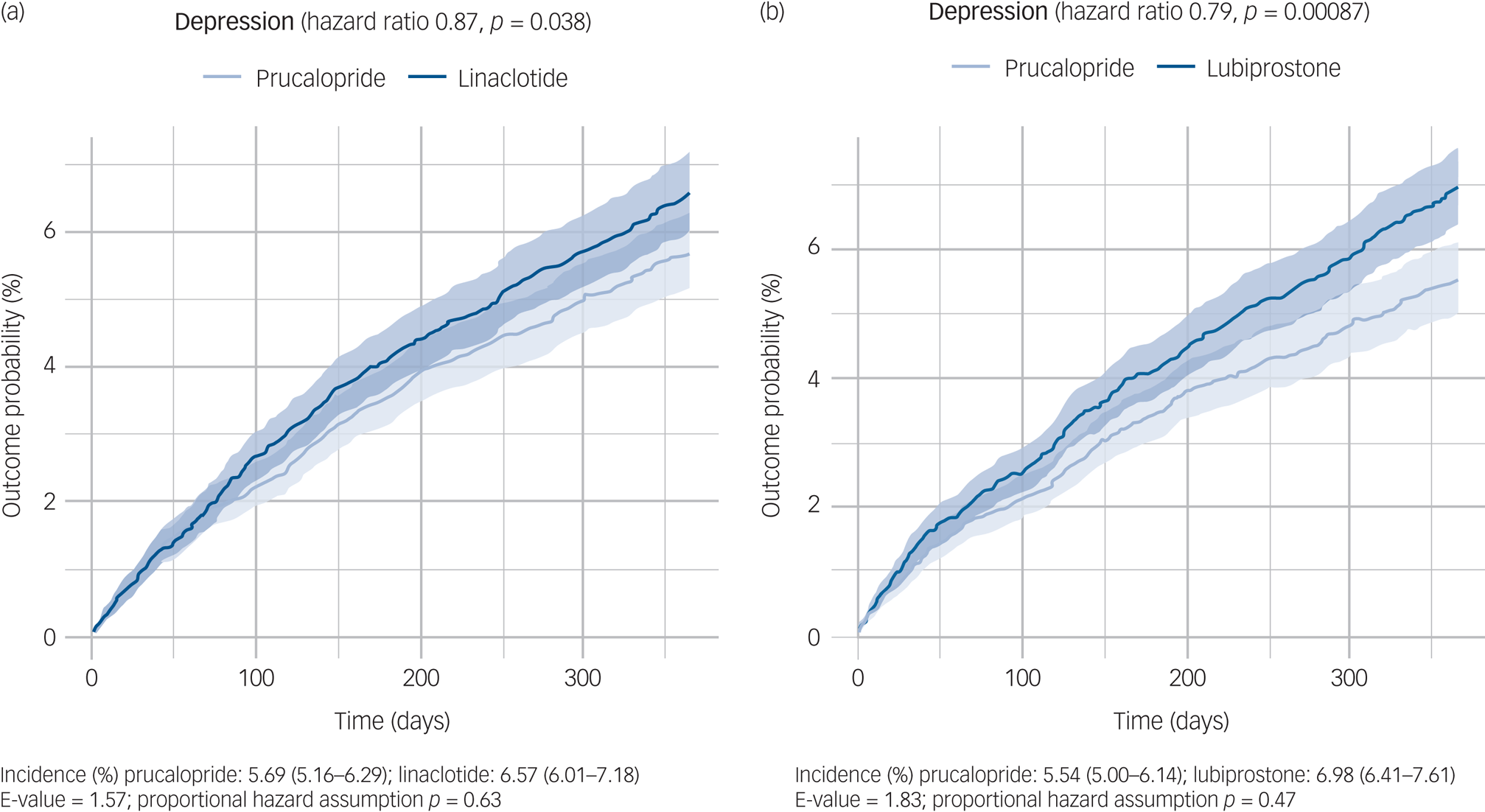

In the year following a first prescription, those prescribed prucalopride had a significantly lower incidence of depression (prucalopride versus linaclotide: hazard ratio 0.87, 95% CI 0.76–0.99, P = 0.038, E = 1.58; prucalopride versus lubiprostone: hazard ratio 0.79, 95% CI 0.69–0.91, P < 0.001, E = 1.83; Fig. 2). There was no evidence of non-proportional hazards for either comparison (P = 0.63 and 0.47, respectively).

Fig. 2 Kaplan–Meier curves showing the cumulative incidence of depression diagnosis over 12 months in those receiving (a) prucalopride versus linaclotide and (b) prucalopride versus lubiprostone. The shaded areas around curves represent 95% CI.

These results were replicated in all robustness analyses for lubiprostone, and all but one for linaclotide (Supplementary Table 6). In particular, the findings held when we excluded participants who had a contraindication for any drug being compared, patients who crossed over to the other ‘arm’ of the comparison within the 1-year follow-up period or patients who had a recent prescription of one of the two most common SSRI antidepressants. The only exception was the comparison with linaclotide when participants with a broader range of neuropsychiatric diagnoses were excluded, which resulted in a non-significant association of similar effect size (hazard ratio 0.87, 95% CI 0.76–1.00, P = 0.058).

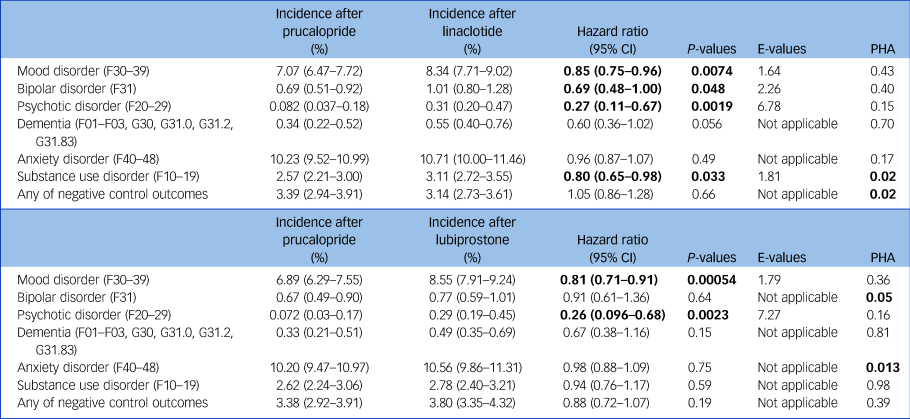

In terms of secondary outcomes (Table 2 and Supplementary Figs 1 and 2), compared with linaclotide and lubiprostone, those prescribed prucalopride had a lower incidence of all mood disorders (prucalopride versus linaclotide: hazard ratio 0.85, 95% CI 0.75–0.96, P = 0.0074; prucalopride versus lubiprostone: hazard ratio 0.81, 95% CI 0.71–0.91, P < 0.001) and psychotic disorder (prucalopride versus linaclotide: hazard ratio 0.27, 95% CI 0.11–0.67, P = 0.0019; prucalopride versus lubiprostone: hazard ratio 0.26, 95% CI 0.096–0.68, P = 0.0023). Results for these two secondary outcomes were replicated in all robustness analyses (Supplementary Tables 7–11). Findings for other outcomes, including dementia, bipolar disorder and substance misuse, varied in significance across analyses.

Table 2 Results for secondary outcomes comparing matched cohorts of individuals prescribed prucalopride versus linaclotide/lubiprostone

Incidences reported at 1 year. Bold values for hazard ratios and P-values indicate statistical significance. The proportional hazard assumption (PHA) is rejected if P < 0.05 (Supplementary Fig. 4).

No significant differences in negative outcomes were observed (see Supplementary Tables 7–12). We also found no significant difference between matched cohorts in terms of risk of needing an enema (prucalopride versus linaclotide: hazard ratio 1.02, 95% CI 0.14–7.23, P = 0.99; prucalopride versus lubiprostone: hazard ratio 2.09, 95% CI 0.19–23.12, P = 0.53).

There was no significant difference in risk of depression between linaclotide and lubiprostone (n = 78 581 in each matched cohort; hazard ratio 1.00, 95% CI 0.95–1.04, P = 0.83), indicating that medication price is unlikely to confound the association (Supplementary Table 13; for rationale, see Method). Similarly, there was no significant difference in incidence of depression between linaclotide and plecanatide (n = 2405 patients in each matched cohort; hazard ratio 1.10, 95% CI 0.85–1.42, P = 0.46), indicating that Medicaid/Medicare availability date is unlikely to confound the association (Supplementary Table 14).

In the interrupted time-series analysis, the incidence of depression significantly decreased after prescription of prucalopride (−3.05 cases/10 000 people per month, 95% CI −4.95 to −1.14, P = 0.0058; no evidence of autocorrelation, P = 0.63; Fig. 3(a)). This finding was robust when 2 months on either side of prucalopride prescription were included, and when absolute counts rather than incidence were analysed (Supplementary Table 15). Conversely, no decrease in incidence of negative control outcomes was observed over the follow-up period (+1.53 cases/10 000 people per month, 95% CI 0.12–2.93, P = 0.047; Fig. 3(b)).

Fig. 3 Interrupted time-series analysis comparing (a) the incidence of depression and (b) any negative control outcomes, before and after prucalopride prescription, shown as a proportion of people who had a healthcare encounter during each month.

Discussion

In this emulated target trial, the highly selective 5-HT4R agonist, prucalopride, was associated with a 13–21% lower risk of a first episode of depression within the following year, compared with matched cohorts of patients prescribed drugs with similar indication but without action at the 5-HT4R (linaclotide and lubiprostone). This study is the first to consider the mental health effects of prucalopride by using clinical health records, and adds to a growing evidence base highlighting the potential role of 5-HT4R agonists in depression. It may also help to inform the choice of anti-constipation drug in people with chronic constipation who are at risk of depression.

The research question of this study lends itself well to an emulated target trial for two reasons: (a) all three drugs are third-line interventions for chronic constipation,Reference Chang, Chey, Imdad, Almario, Bharucha and Diem17 and the choice between the three is largely driven by clinician's preference, thus limiting indication and selection bias; and (b) there is no a priori reason for patients and clinicians to have believed that these drugs would have differential effects on mental health, thereby limiting detection bias.

There are several mechanisms through which 5-HT4R agonism might reduce depression risk. First, 5-HT4R agonists may have a direct effect on mood after penetrating the blood–brain barrier, with evidence of increased brain derived neurotrophic factor/cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element binding protein production and direct action on the raphe nucleus in preclinical studies.Reference Lucas, Rymar, Du, Mnie-Filali, Bisgaard and Manta8,Reference Mendez-David, David, Darcet, Wu, Kerdine-Romer and Gardier9 Second, 5-HT4R agonists have procognitive effects in animalReference King, Marsden and Fone10 and human models of learning.Reference de Cates, Wright, Martens, Gibson, Turkmen and Cowen12,Reference de Cates, Martens, Wright, Gould van Praag, Capitao and Cowen21 Third, the association between prucalopride and depression may be mediated by action on the gut–brain axis, including effects on the microbiome or gut serotonin.Reference Shine, O'Callaghan, Walpola, Wainstein, Taylor and Aru22 Fourth, prucalopride may be acting to increase stress resilience: 5-HT4R agonists decrease stress-induced depressive-type behaviours in rodent models.Reference Chen, Mendez-David, Luna, Faye, Gardier and David23

The most striking reduction in risk with prucalopride was not for depression, but for psychotic disorders. However, it is a post hoc finding that we did not hypothesise, and the very low incidence and wide confidence intervals lead us to interpret this finding, as for bipolar disorder, with great caution. Moreover, in contrast to depression, the Kaplan–Meier curves for psychotic disorder show earlier separation between cohorts for the comparison with linaclotide, increasing the likelihood that the findings are related to unmeasured confounding. Nevertheless, the potential procognitive profile of 5-HT4R agonism may be a transdiagnostic mechanism through which prucalopride lowers the risk for both depression and other psychiatric disorders. Thus, the possibility of benefits of 5-HT4R agonism on psychosis merits investigation in additional, and younger, cohorts.

In emulated target trials, it is important to consider whether there are systematic differences between the groups exposed to one drug versus another, which may confound the findings. Importantly, the three drugs compared in this study have the same clinical indication, and the cohorts were well matched on a wide range of covariates at baseline. With E-values of 1.58 and 1.83 for the main analyses, any residual confounder would need to be associated with both the exposure and the outcome, with a relative risk of 1.58–1.83, to explain away the observed association. Furthermore, results from the robustness analyses argue against the possibility of such a large residual confounding. For example, replication after excluding those with a recent prescription of the most commonly used SSRIs (often prescribed for menopause and irritable bowel syndrome) eliminates a possible differential impact of these drugs on outcomes. The absence of a difference in depression incidence between other anti-constipation agents with difference in prices and Medicaid/Medicare approval status suggests that those factors were not driving the observed differences. The overlap between Kaplan–Meier curves in the early phase of follow-up argues against obvious selection bias, which can manifest as effects that appear too early.Reference Mohyuddin and Prasad24 Finally, the findings from interrupted time-series analysis provide further evidence that initiation of prucalopride may decrease the risk of depression, and complements the emulated target trial design: the former benefits from better control of unmeasured time-invariant covariates, whereas the latter distinguishes the effect of 5-HT4R agonism from a generic anti-constipation effect.

Our study has several strengths, including a large sample size, propensity score matching for a wide range of covariates and consistency of findings across robustness analyses. However, it also has limitations. Some are generic to studies based on electronic health records, including coding errors, patients receiving care outside of the network and the uncertain adherence to medications (which is why this study emulates an intention-to-treat analysis). There are also limitations specific to this study. First, it is possible that the effect of prucalopride on depression is partly mediated by better control of constipation than comparator drugs. However, network meta-analyses have shown no significant differences in efficacy between these drugs in the treatment of chronic idiopathic constipationReference Nelson, Camilleri, Chirapongsathorn, Vijayvargiya, Valentin and Shin25 and opioid-induced constipation,Reference Sridharan and Sivaramakrishnan26 and enema use was similar between cohorts. Second, we could not estimate robust variances accounting for the same individuals being potentially present in two cohorts (if a patient received both prucalopride and one of the comparator drugs at two different time points), since identification of patients across cohorts could threaten anonymity. However, results were robust when mutually exclusive cohorts were used (for which the variance estimates of this study are valid) and after excluding patients who crossed over to the other cohort during follow-up, suggesting that variance estimates did not result in false positive findings. This is also supported by the minimal overlap between prucalopride and linaclotide/lubiprostone cohorts (Supplementary Fig. 3). Other limitations include uncertainty about whether findings generalise to patients without constipation or in countries outside of the USA; sample sizes were insufficient to stratify analyses by gender or age; and a diagnosis of chronic constipation could not be confirmed in all included participants in the cohorts, as it is notoriously undercoded in electronic health records.Reference Doshi, Cai, Buono, Spalding, Sarocco and Tan27 Therefore, some patients might have received these drugs off-label for other indications. Finally, it is possible that clinicians may be more cautious of prucalopride in patients potentially at risk of mental illness, because of early FDA warnings of a risk of increased suicidal thoughts or behaviour. The focus on first episode of depression in people with no history of mental illness mitigates this risk. In addition, people with a history of mental illness are actually more likely to be prescribed prucalopride than either comparator drug (Supplementary Table 16).

Despite the exclusion of people with a previous diagnosis of common and/or serious mental illness in our primary analysis, antidepressant use in our sample is high (see Table 1 and Supplementary Tables 3–5). This is likely because of the common usage of antidepressants, especially non-SSRIs, for reasons other than depression (or anxiety) in people with chronic gastrointestinal illness, such as pain and urinary symptoms. Excluding all people with a history or concurrent use of antidepressants would therefore challenge the external validity of our findings. To address any bias from differences in use of antidepressants, these were included as covariates (both as a class and as individual agents) and matched for. Their large prevalence in the cohorts leaves the possibility that the observed associations reflect a synergistic effect between 5-HT4R agonists and antidepressants, as suggested by preclinical evidence.Reference Licht, Knudsen and Sharp28

This emulated target trial provides robust clinical evidence that prucalopride is associated with a lower risk of depression in those with no previous diagnosis, compared with alternative anti-constipation agents, supporting the hypothesis that 5-HT4R agonists have antidepressant properties. This evidence lends strong support for further investigation of the effect of 5-HT4R agonists on depression within a randomised controlled trial, and consideration for its use within other mental illnesses.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2024.97

Data availability

As described in the Method section, the TriNetX USA Collaborative Network was used for this study. This is a cloud-based network that can access anonymised data from electronic health records in multiple healthcare organisations, in the USA. Each healthcare organisation remains anonymous within TriNetX, and is able to provide data with the necessary consents and approvals as long as research is the sole use. Data de-identification is formally attested as per Section §164.514(b)1 of the HIPAA Privacy Rule, superseding TriNetX's waiver from the Western Institutional Review Board; no further ethical approval was thus needed. As we used anonymised routinely collected data, no participant consent was required. The TriNetX system returned the results of these analyses as csv files, which we downloaded and archived. Aggregate data, as presented in this article, can be freely accessed in the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/zqf4s/. The data used for this article were acquired from TriNetX. This study had no special privileges. Inclusion criteria specified in the methods would allow other researchers to identify similar cohorts of patients as we used here for these analyses; however, TriNetX is a live platform with new data being added daily, so exact counts will vary. To gain access to the data, a request can be made to TriNetX ([email protected]), but costs might be incurred, and a data-sharing agreement would be necessary. The analytic code used in this study is openly accessible to any reviewer, upon request to the corresponding author, A.N.d.C.

Acknowledgements

P.J.H. and M.T. were granted unrestricted access to the TriNetX network for the purposes of research, and with no constraints on the analyses done or the decision to publish. The authors would like to thank Miss Grace Warner for her support in preparing some of the tables for this manuscript. Fig. 1 was created using Biorender.com.

Author contributions

A.N.d.C., C.J.H., P.J.H., S.E.M. and M.T. designed the study, with input from A.E., S.T. and P.J.C. A.N.d.C. and M.T. undertook all analyses. A.N.d.C. wrote the first draft of the report with S.E.M. and M.T., and all authors contributed to and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors had access to the data in this study and had final responsibility to submit for publication.

Funding

A.N.d.C. is currently a National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) clinical lecturer and was funded by a Wellcome Trust Clinical Doctoral Fellowship (award 216430/Z/19/Z) and Guarantors of Brain Clinical Postdoctoral Fellowship at the time of preparation for this work and analyses. A.N.d.C., C.J.H., P.J.H., S.E.M. and M.T. were/are supported by the Oxford Health NIHR Biomedical Research Centre (grant number NIHR203316). P.J.C. is a Medical Research Council clinical scientist. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Wellcome Trust, Guarantors of Brain, NHS, NIHR or UK Department of Health. None of these bodies had a significant role in the design, collection and analysis of data, or decision to publish this article.

Declaration of interest

TriNetX were not involved in the design, analysis or interpretation of the data. A.N.d.C. is a trainee editor for the British Journal of Psychiatry, and has received a travel grant from the Royal College of Psychiatrists/Gatsby Foundation. C.J.H. has received consultancy fees from P1vital, Ieso, UCB, J&J and Lundbeck in the last 3 years. She is a co-director of TnC Psychiatry Ltd. S.E.M. has received consultancy fees from Zogenix, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, UCB Pharma and Janssen Pharmaceuticals. She holds grant income from Janssen Pharmaceuticals. S.T. has received research support from AbbVie, Buhlmann, Celgene, Celsius, ECCO, Helmsley Trust, IOIBD, Janssen, Lilly, Pfizer, Takeda, UKIERI, Vifor and Norman Collisson Foundation; consulting fees from AbbVie, ai4gi, Allergan, Amgen, Apexian, Arcturis, Arena, AstraZeneca, Bioclinica, Biogen, BMS, Buhlmann, Celgene, ChemoCentryx, Clario, Cosmo, Dynavax, Endpoint Health, Enterome, EqrX, Equillium, Ferring, Galapagos, Genentech/Roche, Gilead, GSK, Immunocore, Indigo, Janssen, Lilly, Mestag, Microbiotica, Novartis, Pfizer, Phesi, Protagonist, Sanofi, Satisfai, Sensyne Health, Sorriso, Syndermix, Takeda, Theravance, Topivert, UCB Pharma, Vhsquared and Vifor; and speaker fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Biogen, BMS, Falk, Ferring, Janssen, Lilly, Pfizer and Takeda. All other authors have nothing to declare.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.