Clozapine is a unique agent in the treatment of schizophrenia. It is significantly more effective in treating positive and negative symptoms than other antipsychotics but it can cause serious side-effects of agranulocytosis in a significant proportion (0.8%) of patients (Reference Alvir, Lieberman and SaffermanAlvir et al, 1993).

It has received strong endorsement as a cost-effective therapy by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in their guidance on the use of new antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2002). It is recommended for all patients who are treatment resistant (i.e. who have failed to respond adequately to a trial of two antipsychotic medications). This implies that around 18% of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia could be treated with clozapine.

Starting and stabilising a patient on clozapine has greater resource implications for mental health staff and patients than any other antipsychotic medication. Treatment usually requires initiation in hospital or intensive monitoring in the community (for example home treatment or day hospital).

Large variation in its utility has been noted in a previous study. In 2000 a 34-fold variation in prescribing practices was reported (Reference Purcell and LewisPurcell & Lewis, 2000) among 12 trusts over 3 years, and this degree of maximum variation was stable over that period. Non-evidence-based practice was cited as the main contributing factor for low prescribing of clozapine, with cost and licensing restrictions compounding the reluctance to utilise the drug. A study in 2003 in the same region (Reference Hayhurst, Brown and LewisHayhurst et al, 2003) revealed a 16-fold variation per capita use of clozapine between local mental health trusts.

Since the publication in 2002 of the NICE guidelines on the treatment of schizophrenia, and the significant reduction of the cost of clozapine after it came off patent in 2004, we hypothesised that access to clozapine would increase and become more consistent. We are not aware of any further studies on the topic. We were also interested to explore whether, owing to the diverse clinical, logistic, and patient-orientated resources that are required to implement successful clozapine therapy, the overall performance of a mental health trust could be implicated in its delivery.

We believe that a trust's performance in making clozapine available to its population reflects on this trust's ability to:

-

• implement evidence-based treatment

-

• devolve resources to the people most severely affected by mental illness

-

• deliver interventions that imply a significant amount of active work with patients, negotiate informed consent and foster consistent engagement with services

-

• to sustain sound organisational structures in running clozapine clinics.

At the time of this study the only measure available to judge a trust's global performance on clinical, logistic and patient-centered service delivery was the Commission for Health Improvement (now Healthcare Commission) star rating scheme. The question emerged whether a trust's performance (star rating) correlated with the availability of clozapine to its population.

Method

All pharmacies that supplied the 75 English mental health trusts that were using clozapine were contacted in 2005–2006 and invited to supply details on the number of patients that were receiving clozapine at a single point in time and the approximate population size their trust served.

Star ratings for each trust were taken from the 2004–2005 results published by the Healthcare Commission in 2005.

Clozapine prescribing ratios were then adjusted according to the trust's population and deprivation, using the Mental Illness Needs Index (MINI) predicted prevalence (Reference GloverGlover, 1998) to account for the variation in mental health service use.

Results

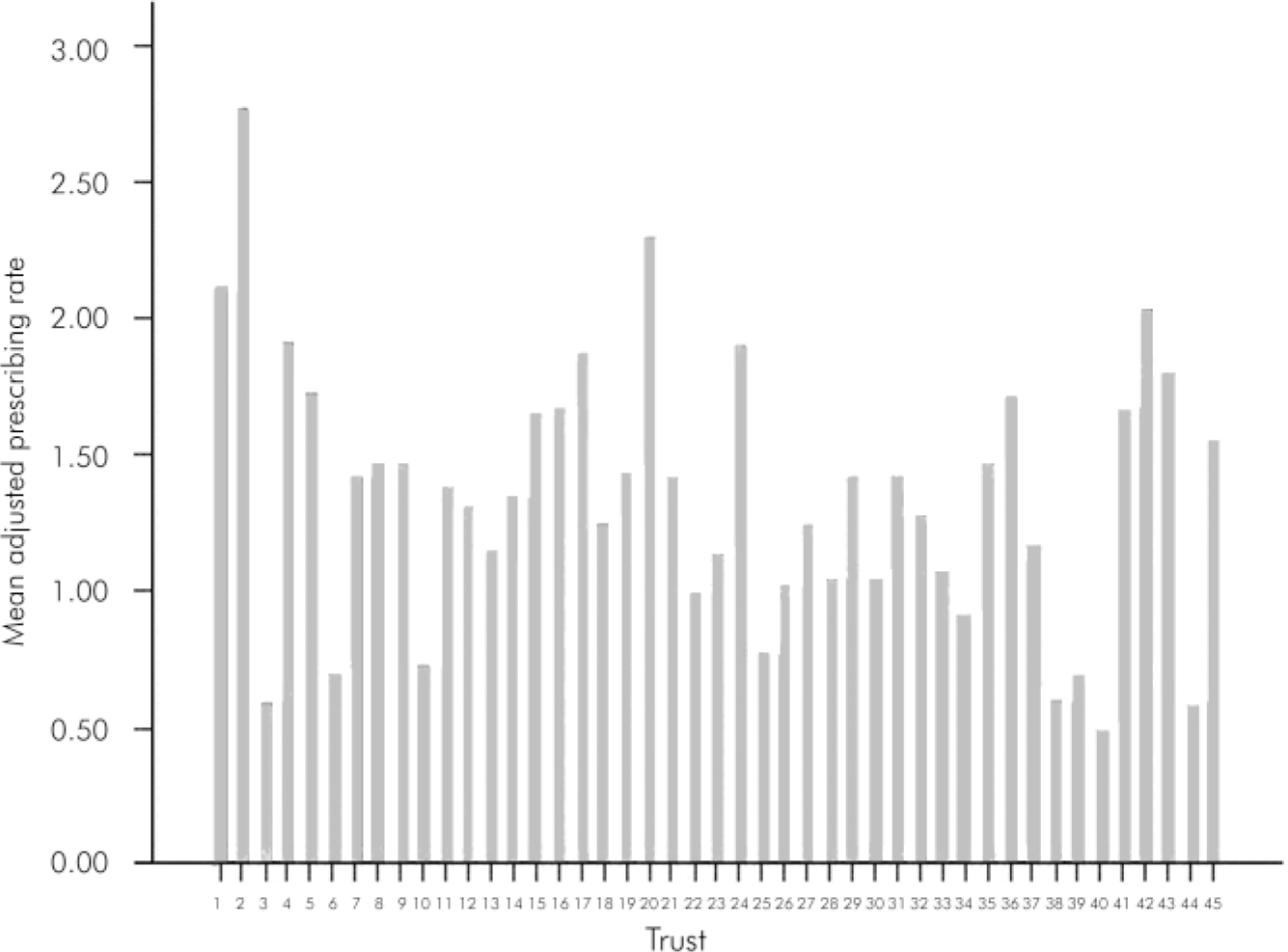

We received information from 45 trusts by September 2006. A total of 10 678 patients were receiving clozapine from a population of 29.4 million (see Table 1). There was a maximum 5-fold variation (adjusted by population and MINI) among trusts’ prescribing rates (see Fig. 1).

Table 1. People receiving clozapine by trust

| Trust | Population, n | No. patients on clozapine, n | Clozapine per 10 000 n | Mini Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 475 000 | 163 | 3.43 | 1.63 |

| 2 | 800 000 | 392 | 4.90 | 1.77 |

| 3 | 250 000 | 30 | 1.20 | 2.02 |

| 4 | 240 000 | 75 | 3.13 | 1.63 |

| 5 | 990 000 | 435 | 4.39 | 2.54 |

| 6 | 500 000 | 95 | 1.90 | 2.70 |

| 7 | 320 000 | 120 | 3.75 | 2.64 |

| 8 | 190 000 | 65 | 3.42 | 2.34 |

| 9 | 1600 000 | 552 | 3.45 | 2.35 |

| 10 | 570 000 | 130 | 2.28 | 3.11 |

| 11 | 1200 000 | 538 | 4.48 | 3.22 |

| 12 | 500 000 | 150 | 3.00 | 2.29 |

| 13 | 950 000 | 252 | 2.65 | 2.31 |

| 14 | 550 000 | 221 | 4.02 | 2.99 |

| 15 | 650 000 | 450 | 6.92 | 4.19 |

| 16 | 1000 000 | 303 | 3.03 | 1.82 |

| 17 | 1300 000 | 730 | 5.61 | 3.01 |

| 18 | 750 000 | 275 | 3.67 | 2.93 |

| 19 | 1100 000 | 339 | 3.08 | 2.14 |

| 20 | 650 000 | 300 | 4.61 | 2.01 |

| 21 | 330 000 | 114 | 3.45 | 2.43 |

| 22 | 800 000 | 275 | 3.43 | 3.47 |

| 23 | 1200 000 | 394 | 3.28 | 2.88 |

| 24 | 260 000 | 110 | 4.20 | 2.23 |

| 25 | 320 000 | 72 | 2.25 | 2.90 |

| 26 | 1200 000 | 505 | 4.21 | 4.10 |

| 27 | 240 000 | 60 | 4.00 | 2.02 |

| 28 | 500 000 | 100 | 2.00 | 1.91 |

| 29 | 1100 000 | 475 | 4.32 | 3.05 |

| 30 | 1000 000 | 290 | 2.90 | 2.75 |

| 31 | 690 000 | 430 | 6.23 | 4.38 |

| 32 | 880 000 | 358 | 4.07 | 3.17 |

| 33 | 200 000 | 63 | 3.15 | 2.92 |

| 34 | 555 000 | 150 | 2.70 | 2.92 |

| 35 | 491 000 | 220 | 4.48 | 3.04 |

| 36 | 500 000 | 186 | 3.72 | 2.16 |

| 37 | 305 155 | 78 | 2.56 | 2.18 |

| 38 | 100 000 | 19 | 1.90 | 3.16 |

| 39 | 600 000 | 100 | 1.67 | 2.44 |

| 40 | 1000 000 | 91 | 0.91 | 1.84 |

| 41 | 400 000 | 177 | 4.43 | 2.65 |

| 42 | 736 000 | 375 | 5.10 | 2.50 |

| 43 | 625 000 | 216 | 3.46 | 1.91 |

| 44 | 275 000 | 48 | 1.75 | 2.95 |

| 45 | 520 000 | 157 | 3.02 | 1.93 |

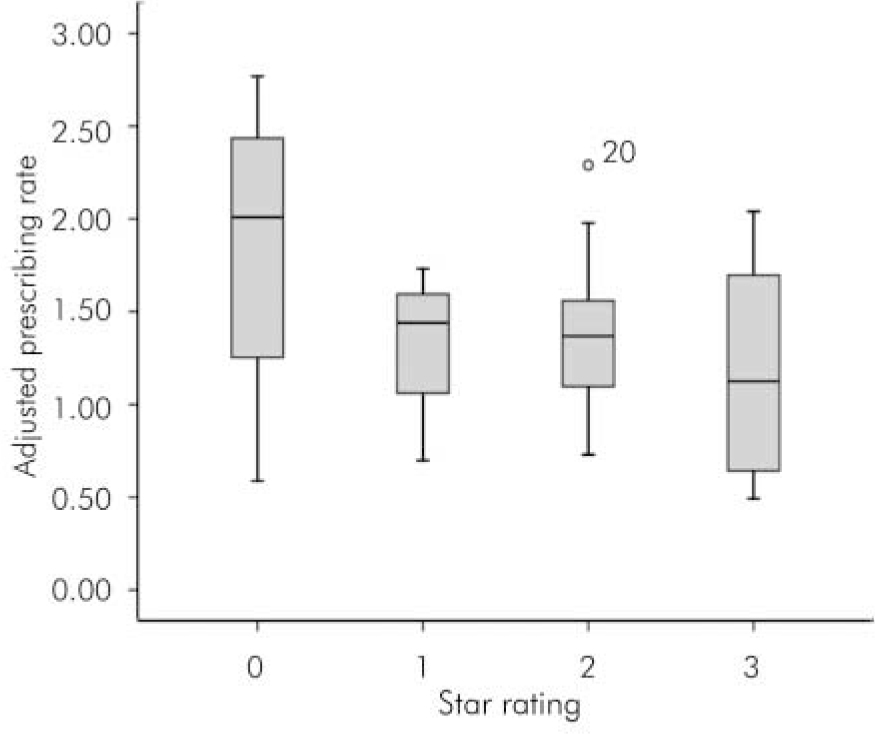

Regression analysis demonstrated a small inverse relationship between a trust's star rating and its adjusted clozapine prescribing rates (see Fig. 2). A 1-star increase correlated with a 10% decrease in ratio (P=0.045). For the average trust in our sample (population 680 000 and MINI 2.67) a 1-star increase relates to a reduction in 31 patients receiving clozapine.

Fig. 1. Adjusted clozapine prescribing rates for 45 trusts in England.

Fig. 2. Adjusted clozapine prescribing rates according to Healthcare Commission star rating.

Discussion

This study describes the prescribing patterns for clozapine for 60% of the mental health trusts in England. According to the NICE guidelines (2002) 63 000 individuals would be eligible for clozapine in England. At that time, they estimated 13 500 were receiving clozapine (21% of those eligible). Using our figures sampling 56% of England's population (29.4 million; Office for National Statistics) we found 10 678 receiving clozapine, equivalent to 30% of those eligible.

Compared with an earlier study published before NICE guidelines were circulated and clozapine became available off patent (Reference Purcell and LewisPurcell & Lewis, 2000), there has been a significant reduction from the previously recorded maximum 34-fold inter-trust variation to 5-fold.

Although the Healthcare Commission no longer uses star ratings as an overall measure to distinguish high- and low-performing trusts, we still thought it relevant that a trust's prior star rating bore no relation to a trust's ability to institute a complex psychiatric intervention like clozapine initiation and maintenance. This may be a reflection on pharmacies and clinicians acting in isolation from the standards of the rest of the trust. More likely is that robust measures of judging clinical quality of care have not been incorporated into the healthcare ratings system and were not adequately reflected in the star ratings. It is suggested in this study that a trust that is deemed to be a poor performer by star rating may give excellent care provision to its most complex patient cohort. The finding of an inverse correlation between star ratings and clozapine use should just highlight that clinical activity may be removed from the appraisal of a trust's overall performance. We question whether inclusion of a clozapine prescribing item in future ratings might focus our efforts a little more towards those with severe mental illness and evidence-based interventions.

This study is limited by the information that has been supplied by individual trusts, which may be subject to bias. The response was voluntary but marginally weakened by selection bias with 60% representation of all mental health trusts, with no clustering of trusts to national regions. We were unable to exclude all national and forensic unit populations, but trusts were encouraged to provide information pertaining to secondary care.

Declaration of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the pharmacists from the 45 trusts, with special thanks to Bruce Brown. Thanks also to Dr Rosemary Tate for her statistical advice.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.