Schizophrenia is a serious mental illness that has a profound effect on the patients, their families and society. Reference Owen, Sawa and Mortensen1 Despite its low prevalence in populations, schizophrenia is associated with an enormous economic burden worldwide. Reference Chong, Teoh, Wu, Kotirum, Chiou and Chaiyakunapruk2 In the USA, the economic burden of schizophrenia was estimated at 62.7 billion dollars in 2002 Reference Wu, Birnbaum, Shi, Ball, Kessler and Moulis3 and 155.7 billion dollars in 2013. Reference Cloutier, Aigbogun, Guerin, Nitulescu, Ramanakumar and Kamat4 Patients with schizophrenia are known to have a significantly higher risk of premature death, Reference Saha, Chant and McGrath5–Reference Laursen, Nordentoft and Mortensen7 with nearly 20% shorter life expectancy than the general population. Reference Chou, Tsai, Wu and Shen8 Although unnatural causes of death such as suicide, homicide and accidents partly contribute to the excess mortality of schizophrenia, more patients actually died from natural causes, such as cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases and cancers. Reference Olfson, Gerhard, Huang, Crystal and Stroup9–Reference Walker, McGee and Druss12 In Sweden, natural causes accounted for 90.9% and 82.3% of all deaths among women and men with schizophrenia respectively. Reference Crump, Winkleby, Sundquist and Sundquist13 In a previous systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia, the median standardised mortality ratios (SMRs) were 2.58, 2.41 and 7.50 for mortality from all causes, natural causes and unnatural causes respectively, when comparing patients with schizophrenia with the general population. Reference Saha, Chant and McGrath5

During recent decades, there has been an immense interest in estimating the risk of cancer mortality after a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Findings from previous studies have been mixed with positive, null and inverse associations between schizophrenia and cancer mortality. Several studies, in particular early studies, reported a lower or similar risk of cancer mortality among patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population. For instance, in a retrospective cohort study (1957–1986) in Denmark, Mortensen & Juel reported a 15% lower risk of cancer mortality in men but a 17% higher risk of cancer mortality in women. Reference Mortensen and Juel14 Similar results were found in subsequent studies in Japan Reference Saku, Tokudome, Ikeda, Kono, Makimoto and Uchimura15 and West Australia. Reference Lawrence, Holman, Jablensky, Threlfall and Fuller16 However, a positive association between schizophrenia and cancer mortality was observed in other studies in a Danish population Reference Laursen, Munk-Oisen, Nordentoft and Mortensen17,Reference Castagnini, Foldager and Bertelsen18 and studies in other populations. Reference Olfson, Gerhard, Huang, Crystal and Stroup9,Reference Brown, Kim, Mitchell and Inskip10,Reference Crump, Winkleby, Sundquist and Sundquist13,Reference Heila, Haukka, Suvisaari and Lonnqvist19–Reference Kisely, Forsyth and Lawrence27 In a large national cohort in the USA, Olfson et al Reference Olfson, Gerhard, Huang, Crystal and Stroup9 found that adults with schizophrenia had a 1.8-fold chance of dying from cancers compared with adults in the general population. Similarly, paradoxical findings were also reported in literature pertaining to cancer incidence after a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Reference Hodgson, Wildgust and Bushe28–Reference Dalton, Laursen, Mellemkjaer, Johansen and Mortensen31 Cancers are usually invasive and life-threating; thus, it is important to accurately characterise cancer mortality patterns after a diagnosis of schizophrenia, which may help inform changes in clinical care to reduce cancer-related deaths in patients with schizophrenia. However, because the prevalence of both schizophrenia and cancer mortality are very low, a robust estimate of the association between schizophrenia and cancer mortality may not have been achievable in some previous studies. Therefore, this study was performed to systematically review the currently available evidence regarding cancer mortality in patients with schizophrenia and to quantify the association between schizophrenia and cancer mortality through a comprehensive meta-analysis.

Method

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines in the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement. Reference Stroup, Berlin, Morton, Olkin, Williamson and Rennie32

Literature searches

We searched the PubMed and Embase databases for literature that was published up to 16 October 2016. The search terms were a combination of key words and standard subheading terms relevant to schizophrenia, cancer and mortality. Specifically, we used the following search terms in PubMed: (“Schizophrenia”[Mesh] or “schizophrenia”[tiab] or “schizophrenic”[tiab]) AND (“Neoplasms”[Mesh] or “cancer”[tiab] or “tumor”[tiab]) AND (“Mortality”[Mesh] or “mortality”[tiab] or “death”[tiab]). Similar search terms were constructed and used in the Embase database. Additionally, the references listed in any relevant articles or reviews were screened. No language restrictions were applied for the searches or study inclusion.

Study selection and data extraction

Any published article that reported the risk of cancer mortality in patients with schizophrenia was eligible for inclusion in this systematic review. During the screening steps, we excluded reviews, editorials or protocols that did not include original data. We also excluded studies on animals or cell lines, studies that did not evaluate schizophrenia as an exposure variable, and studies that did not include cancer mortality as an outcome variable. After detailed evaluation, we excluded studies if risk estimates and/or confidence intervals for the association between schizophrenia and cancer mortality were not reported and were unable to be calculated. We also excluded two studies Reference Brown, Inskip and Barraclough33,Reference Grigoletti, Perini, Rossi, Biggeri, Barbui and Tansella34 in which the results were updated by later reports Reference Brown, Kim, Mitchell and Inskip10,Reference Perini, Grigoletti, Hanife, Biggeri, Tansella and Amaddeo35 with longer follow-up in the same population. Another study was excluded because the participants already had cancer at baseline, with a focus on cancer fatality rather than mortality from cancer. Reference Batty, Whitley, Gale, Osborn, Tynelius and Rasmussen36

The following data were extracted from each included article: title, author, publication year, location, study design, number of participants, methods used for the assessment of schizophrenia and cancer death, statistical methods used for the analysis, risk estimates and 95% confidence intervals after adjustment for covariates, and any covariates that were adjusted or matched for in the multivariate model. When the original studies reported the results separately in men and women we considered them independent populations and extracted the risk estimates separately.

Statistical analysis

Risk estimates and 95% confidence intervals reported in individual studies were pooled in a meta-analysis using the DerSimonian–Laird random-effects model, which incorporates between-study heterogeneity in addition to sampling variation. Reference DerSimonian and Laird37 The majority of studies on cancer mortality in patients with schizophrenia used SMRs compared with the general population as their risk estimates. The relative risk (RR) of cancer mortality in comparing patients with schizophrenia with the general population, as reported in one study, Reference Heila, Haukka, Suvisaari and Lonnqvist19 was assumed to approximate SMRs. Several studies reported hazard ratios (HRs) using a Cox proportional hazards model to compare individuals with schizophrenia with those who did not have schizophrenia. Reference Crump, Winkleby, Sundquist and Sundquist13,Reference Guan, Termorshuizen, Laan, Smeets, Zainal and Kahn23,Reference Almeida, Hankey, Yeap, Golledge, Norman and Flicker25,Reference Kredentser, Martens, Chochinov and Prior26 Therefore, we separately summarised the results as pooled SMRs and pooled HRs in the meta-analysis given the difference in comparator populations. In one study, Reference Kredentser, Martens, Chochinov and Prior26 the 95% confidence intervals were not directly reported, and therefore we calculated these on the basis of reported risk estimates and P-values following the method of Altman & Bland. Reference Altman and Bland38

Heterogeneity across studies was assessed by both the χ2-based Cochran's Q statistic and the I 2 metric. Reference Higgins and Thompson39 To explore the potential sources of heterogeneity, we conducted meta-regression analyses with the following factors: geographical location, sample size (⩾3000 v. <3000), follow-up duration (⩾10 v. <10 years) or adjustment for covariates (age and gender only v. age, gender and other factors). Additionally, we conducted stratified analyses by gender because of the observed gender disparity in several earlier studies.

The possibility of publication bias was visually inspected by funnel plot and statistically assessed using the Egger regression asymmetry test. Reference Egger, Davey Smith, Schneider and Minder40 Sensitivity analyses were performed by omitting one study at a time and calculating a pooled estimate for the remainder of the studies to determine whether the results were markedly affected by a single study. We also used the fixed-effect model for all above analyses as another set of sensitivity analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata software (version 14.0). A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

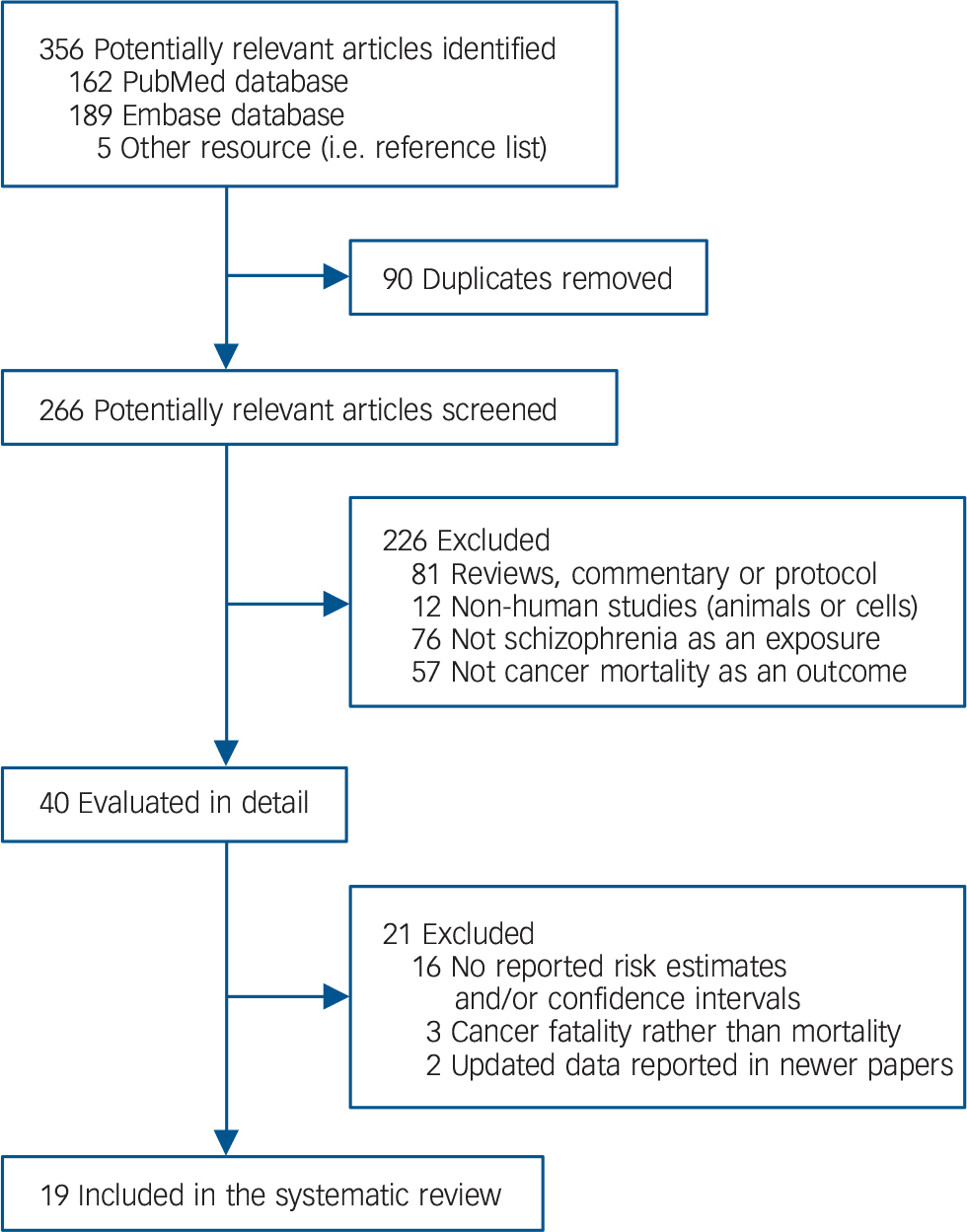

Through a systematic search in literature databases and reference lists of relevant articles, we identified 356 potentially relevant articles. After implementing the screening process, we finally included 19 studies Reference Olfson, Gerhard, Huang, Crystal and Stroup9,Reference Brown, Kim, Mitchell and Inskip10,Reference Crump, Winkleby, Sundquist and Sundquist13–Reference Kisely, Forsyth and Lawrence27,Reference Perini, Grigoletti, Hanife, Biggeri, Tansella and Amaddeo35,Reference Mortensen and Juel41 that fulfilled our eligibility criteria in the meta-analysis (Fig. 1). Two Reference Brown, Kim, Mitchell and Inskip10,Reference Perini, Grigoletti, Hanife, Biggeri, Tansella and Amaddeo35 of the included studies updated the data of their earlier reports Reference Brown, Inskip and Barraclough33,Reference Grigoletti, Perini, Rossi, Biggeri, Barbui and Tansella34 in the same population; thus, the earlier studies Reference Brown, Inskip and Barraclough33,Reference Grigoletti, Perini, Rossi, Biggeri, Barbui and Tansella34 were not included in our list. Of the 19 included studies 11 were conducted in Europe, 4 in Australia, 3 in North America, and 1 in East Asia (Table 1). The majority of the included studies had a retrospective cohort study design with population-based record linkage data. In those studies, schizophrenia was usually defined according to clinical diagnosis in medical records, register, or administrative data and cancer death was ascertained from national or regional registries of vital statistics. The number of patients with schizophrenia in the included studies ranged from 370 to 1 138 853, with most studies having over 1000 patients. The follow-up period varied from 6 to 37 years, and the majority of the included studies had a follow-up duration of 10 years or longer.

Fig. 1 Flow diagram for literature search and study selection.

Table 1 Characteristics of the studies included in the meta-analysis

| Authors, year | Location | Study design | Participants with schizophrenia, n |

Assessment of schizophrenia |

Assessment of cancer death |

Follow-up, years |

Risk estimate (95% CI) |

Adjusted covariates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortensen & Juel (1990) Reference Mortensen and Juel14 |

Denmark | Retrospective cohort study, 1957–1986 |

6178 | Hospital records based on the Kraepelinian concept |

Danish Register of Causes of Death |

29 | SMR: 0.85 (0.76–0.94) in men and 1.17 (1.06–1.28) in women |

Age (reported separately by gender) |

| Mortensen & Juel (1993) Reference Mortensen and Juel41 |

Denmark | Retrospective cohort study, 1970–1987 |

9156 | Danish Psychiatric Case Register | Danish Register of Causes of Death |

17 | SMR: 0.81 (0.54–1.19) in men and 1.01 (0.75–1.33) in women |

Age (reported separately by gender) |

| Saku et al

(1995) Reference Saku, Tokudome, Ikeda, Kono, Makimoto and Uchimura15 |

Japan | Retrospective cohort study, 1948–1985 |

4980 | Medical records, according to DSM-III-R 1987 |

Japanese family registration system (Koseki) and death certificate |

37 | SMR: 0.84 (0.54–1.25) in men and 1.37 (0.80–2.19) in women |

Age (reported separately by gender) |

| Lawrence et al (2000) Reference Lawrence, Holman, Jablensky, Threlfall and Fuller16 |

Australia | Retrospective cohort study, 1982–1995 |

N/A | Western Australian Health Services Research Linked Database |

Western Australian Cancer Register and Death Register |

13 | SMR: 0.90 (0.71–1.80) in men and 1.19 (1.05–1.40) in women |

Age (reported separately by gender) |

| Heila et al

(2005) Reference Heila, Haukka, Suvisaari and Lonnqvist19 |

Finland | Retrospective cohort study, 1980–1996 |

58 761 | Finnish National Hospital Discharge Register |

Finnish National Causes of Death Register |

16 | RR: 1.50 (1.41–1.58) in men and 1.48 (1.40–1.57) in women a |

Age and calendar year (reported separately by gender) |

| Laursen et al (2007) Reference Laursen, Munk-Oisen, Nordentoft and Mortensen17 |

Denmark | Retrospective cohort study, 1973–2000 |

17 660 | Danish Psychiatric Central Register | Danish Register of Causes of Death |

27 | SMR: 1.24 (1.08–1.43) in men and 1.32 (1.18–1.48) in women |

Age and calendar period (reported separately by gender) |

| Tran et al

(2009) Reference Tran, Rouillon, Loze, Casadebaig, Philippe and Vitry20 |

France | Prospective cohort study, 1993–2003 |

3470 | Questionnaire and/or hospital records |

National death certificate | 11 | SMR: 1.5 (1.2–1.9) | Age and gender |

| Brown et al

(2010) Reference Brown, Kim, Mitchell and Inskip10 |

UK | Prospective cohort study, 1981–2006 |

370 | Hospital records | UK Office of National Statistics database |

25 | SMR: 1.93 (1.18–2.98) in men and 1.02 (0.49–1.88) in women |

Age (reported separately by gender) |

| Daumit et al

(2010) Reference Daumit, Anthony, Ford, Fahey, Skinner and Lehman21 |

USA | Retrospective cohort study, 1992–2001 |

N/A | Medicaid database | National Death Index | 9 | SMR: 1.4 (1.3–1.5) | Age, gender and ethnicity |

| Talaslahti et al (2012) Reference Talaslahti, Alanen, Hakko, Isohanni, Häkkinen and Leinonen22 |

Finland | Retrospective cohort study, 1999–2008 |

9461 | Finnish Hospital Discharge Register | National Causes of Death Register of Statistics Finland |

9 | SMR: 1.9 (1.7–2.1) in men and 2.0 (1.8–2.1) in women |

Age (reported separately by gender) |

| Castagnini et al (2013) Reference Castagnini, Foldager and Bertelsen18 |

Denmark | Retrospective cohort study, 1995–2008 |

4576 | Danish Psychiatric Register | Danish Register of Causes of Death |

13 | SMR: 1.5 (1.0–2.3) | Age and gender |

| Crump et al

(2013) Reference Crump, Winkleby, Sundquist and Sundquist13 |

Sweden | Retrospective cohort study, 2001–2009 |

8277 | Swedish Outpatient Registry and Swedish Hospital Registry |

Swedish Death Registry | 9 | HR: 1.39 (1.11–1.74) in men and 1.68 (1.36–2.07) in women |

Age, marital status, education, employment status, income and substance use disorder (reported separately by gender) |

| Guan et al

(2013) Reference Guan, Termorshuizen, Laan, Smeets, Zainal and Kahn23 |

The Netherlands |

Retrospective cohort study, 1999–2009 |

4590 | Psychiatric Case Register Middle Netherlands |

Death Register of Statistics Netherlands |

11 | HR: 1.61 (1.26–2.06) | Age, gender, ethnicity and mean income of last-registered neighbourhood |

| Kisely et al

(2013) Reference Kisely, Crowe and Lawrence24 |

Australia | Retrospective cohort study, 1988–2007 |

N/A | Hospital Morbidity Data System, and Mental Health Information System |

Registrar General's Death Registration Data |

19 | SMR: 2.00 (1.51–2.64) in men and 1.68 (1.29–2.18) in women |

Age and gender |

| Almeida et al (2014) Reference Almeida, Hankey, Yeap, Golledge, Norman and Flicker25 |

Australia | Prospective cohort study, 1996–2010 |

444 | Western Australian Data Linkage System |

Western Australian Data Linkage System |

14 | HR: 2.0 (1.8–2.2) | Age (all participants were men) |

| Kredentser et al (2014) Reference Kredentser, Martens, Chochinov and Prior26 |

Canada | Retrospective cohort study, 1999–2008 |

9038 | Population Health Research Data Repository |

Population Health Research Data Repository |

10 | HR: 1.05 (0.93–1.18) b | Age and gender |

| Perini et al

(2014) Reference Perini, Grigoletti, Hanife, Biggeri, Tansella and Amaddeo35 |

Italy | Retrospective cohort study, 1982–2006 |

695 | South Verona Psychiatric Case Register |

Mortality Registry of the Local Health District of Verona, and other Registries of Deaths |

25 | SMR: 0.83 (0.50–1.30) | Age and gender |

| Olfson et al

(2015) Reference Olfson, Gerhard, Huang, Crystal and Stroup9 |

USA | Retrospective cohort study, 2001–2007 |

1 138 853 | National Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) database |

National Death Index | 7 | SMR: 1.7 (1.7–1.8) in men and 1.8 (1.8–1.8) in women |

Age, ethnicity and geographic region (reported separately by gender) |

| Kisely et al

(2016) Reference Kisely, Forsyth and Lawrence27 |

Australia | Retrospective cohort study, 2002–2007 |

N/A | Queensland Hospital Admitted Patients' Data Collection or Queensland Client Event Services Application |

Queensland Registrar General's Death Registration Data |

6 | SMR: 2.02 (1.61–2.53) | Age, gender, residence, socioeconomic status and length of mental health service in-patient stay |

SMR, standardised mortality ratio; N/A, not applicable; RR, relative risk; HR, hazard ratio.

a. The risk estimates were pooled from the original values that were separately reported for cancer mortality after 0–5, 5–10 and >10 years after the first admission to hospital with schizophrenia.

b. The 95% confidence intervals were not directly reported in the original article, and therefore they were calculated from the P-value along with the risk estimate following the method by Altman & Bland. Reference Altman and Bland38

Association between schizophrenia and cancer mortality

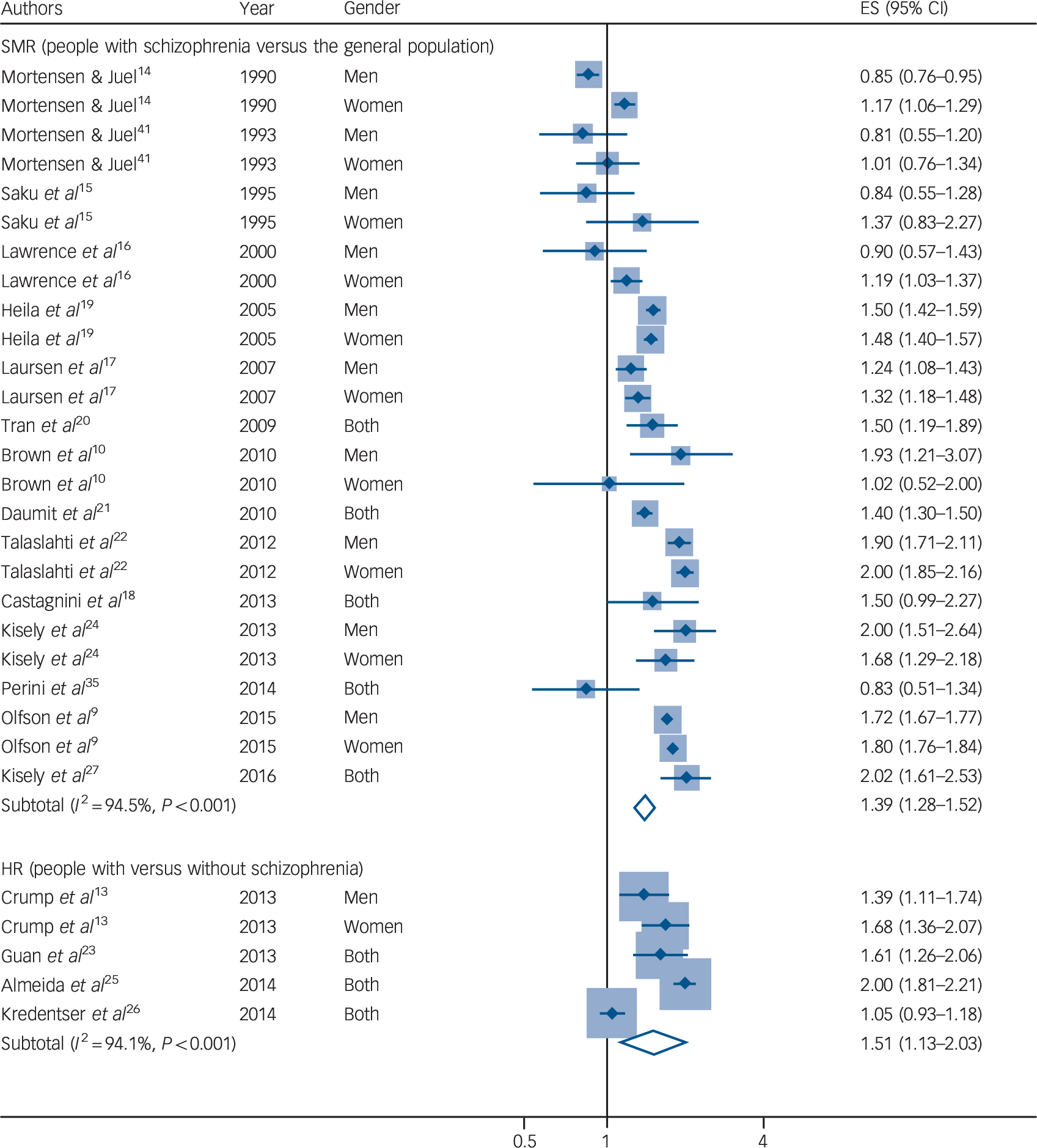

Among the 19 included studies, 15 studies Reference Olfson, Gerhard, Huang, Crystal and Stroup9,Reference Brown, Kim, Mitchell and Inskip10,Reference Mortensen and Juel14–Reference Talaslahti, Alanen, Hakko, Isohanni, Häkkinen and Leinonen22,Reference Kisely, Crowe and Lawrence24,Reference Kisely, Forsyth and Lawrence27,Reference Perini, Grigoletti, Hanife, Biggeri, Tansella and Amaddeo35,Reference Mortensen and Juel41 reported SMRs comparing patients with schizophrenia with the general population. An inverse, null or positive association between schizophrenia and cancer mortality was observed in those studies, with the reported SMRs ranging from 0.81 to 2.02 (Fig. 2). In the random-effects meta-analysis, the pooled SMR of cancer mortality in patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population was 1.40 (95% CI 1.29–1.52; P < 0.001). There was evidence of heterogeneity across studies (I 2 = 95%, P < 0.001). In meta-regression analyses, we observed no evidence that the heterogeneity was caused by a difference in the geographical location, sample size, follow-up duration or adjustment for covariates. In several Reference Brown, Kim, Mitchell and Inskip10,Reference Mortensen and Juel14–Reference Lawrence, Holman, Jablensky, Threlfall and Fuller16,Reference Mortensen and Juel41 although not all Reference Olfson, Gerhard, Huang, Crystal and Stroup9,Reference Laursen, Munk-Oisen, Nordentoft and Mortensen17,Reference Heila, Haukka, Suvisaari and Lonnqvist19,Reference Talaslahti, Alanen, Hakko, Isohanni, Häkkinen and Leinonen22,Reference Kisely, Crowe and Lawrence24 previous studies, a gender difference was noted; however, gender did not appear to be a significant source of heterogeneity in this meta-analysis. Stratified analyses by gender showed that the pooled SMR of cancer mortality was 1.32 (95% CI 1.11–1.57) in men, 1.42 (95% CI 1.24–1.63) in women, and 1.47 (95% CI 1.20–1.79) in studies with both men and women (online Fig. DS1). Further exploration using a cumulative meta-analysis showed evidence of cohort effects; the pooled estimates shifted from an inverse association to a positive association with overall time (online Fig. DS2). There was also evidence for publication bias, as indicated by the funnel plot (online Fig. DS3) and the Egger regression asymmetry test (P < 0.01). Sensitivity analyses by omitting one study at a time did not substantially alter the pooled results, which ranged from 1.37 (95% CI 1.26–1.49) to 1.46 (95% CI 1.35–1.57). Additionally, similar results but with a stronger positive association were obtained when a fixed-effect model was used instead of a random-effects model.

Fig. 2 Forest plot of the risk of cancer mortality in patients with schizophrenia compared with the general population (above) or people without schizophrenia (below).

ES, effect size; HR, hazard ratio; SMR, standard mortality ratio.

The other four studies Reference Crump, Winkleby, Sundquist and Sundquist13,Reference Guan, Termorshuizen, Laan, Smeets, Zainal and Kahn23,Reference Almeida, Hankey, Yeap, Golledge, Norman and Flicker25,Reference Kredentser, Martens, Chochinov and Prior26 reported HRs comparing patients with schizophrenia with those without schizophrenia. All of those studies with the exception of the one by Kredentser et al Reference Kredentser, Martens, Chochinov and Prior26 reported a positive association between schizophrenia and cancer mortality (Fig. 2). The pooled HR of cancer mortality in individuals with schizophrenia compared with those without schizophrenia was 1.51 (95% CI 1.13–2.03, P = 0.006). Similarly, there was evidence for heterogeneity across studies (I 2 = 94%, P < 0.001). Only the study by Crump et al Reference Crump, Winkleby, Sundquist and Sundquist13 reported the HRs separately by gender, in which the HRs were 1.39 (95% CI 1.11–1.74) in men and 1.68 (95% CI 1.36–2.07) in women. We did not perform a meta-regression analysis for those studies because the limited number of included studies did not allow sufficient statistical robustness in meta regression. There was no evidence for significant publication bias (P = 0.84 in the Egger regression asymmetry test). Sensitivity analyses by omitting one study at a time did not substantially alter the pooled results, which ranged from 1.39 (95% CI 1.08–1.80) to 1.69 (95% CI 1.42–2.01). We also observed similar results when a fixed-effect model was used instead of a random-effects model.

Discussion

Main findings

In this study, we found that patients with schizophrenia had a higher risk of cancer mortality. Specifically, the risk of cancer mortality in patients with schizophrenia was 40% higher than the general population and 51% higher than individuals without schizophrenia.

The risk of cancer mortality in patients with schizophrenia has not been previously quantified using a meta-analysis. The present study, based on a systematic review of epidemiological studies, was conducted to provide an updated estimate for the risk of cancer mortality in patients with schizophrenia by pooling original data from individual studies.

Interpretation of our findings and comparison with other studies

In the current study, we observed heterogeneity in previous individual studies looking at the association between schizophrenia and cancer mortality, which was not convincingly explained by differences in gender, geographical location, sample size, follow-up duration or adjusting for covariates. We noted possible cohort effects showing a relatively consistent and positive association in recent publications; this was in contrast to inconsistent associations in earlier publications. However, this may be a result of publication bias, and such findings should be interpreted with caution.

Interestingly, there appeared to be a paradox in the associations between schizophrenia and cancer incidence versus cancer mortality. Reference Hodgson, Wildgust and Bushe28–Reference Dalton, Laursen, Mellemkjaer, Johansen and Mortensen31 Whereas our study showed a significantly increased risk of cancer mortality in patients with schizophrenia, a previous meta-analysis on the association of schizophrenia and cancer incidence showed no significant association in general, although there were variations in the risk of specific cancer sites. Reference Catala-Lopez, Suarez-Pinilla, Suarez-Pinilla, Valderas, Gomez-Beneyto and Martinez30 Several factors have been suggested to explain the divergent associations between schizophrenia and cancer incidence and mortality. Cancer mortality is influenced by not only cancer incidence, but also the survival of those who develop cancer. Reference Saku, Tokudome, Ikeda, Kono, Makimoto and Uchimura15 Several studies on cancer fatality in schizophrenia Reference Batty, Whitley, Gale, Osborn, Tynelius and Rasmussen36,Reference Chou, Tsai, Su and Lee42,Reference Bergamo, Sigel, Mhango, Kale and Wisnivesky43 have consistently indicated that the presence of schizophrenia increases cancer fatality in patients who had cancer (online Table DS1). Compromised accessibility to treatment facilities and lower quality of care may be the primary reasons for the increased cancer mortality observed in patients with schizophrenia, indicating an imperative need to increase access and popularise cancer screening and detection in this patient population. Reference Chou, Tsai, Su and Lee42,Reference Beary, Hodgson and Wildgust44 Reduced cancer screening and delayed cancer diagnosis in those with schizophrenia, which results in a late staging of cancer and a higher prevalence of metastasis at the time of cancer diagnosis, may also contribute to worse cancer survival. Reference Kisely, Crowe and Lawrence24,Reference Cunningham, Sarfati, Stanley, Peterson and Collings45,Reference Mitchell, Pereira, Yadegarfar, Pepereke, Mugadza and Stubbs46 Patients with schizophrenia are also more likely to have physical health multimorbidity, Reference Stubbs, Koyanagi, Veronese, Vancampfort, Solmi and Gaughran47 engage in more smoking, and are less likely to receive smoking cessation advice, Reference Mitchell, Vancampfort, De Hert and Stubbs48 which can increase the risk of cancer mortality. Additionally, different types of antipsychotic drugs may also complicate the risk of cancer mortality in patients with schizophrenia. Reference Tiihonen, Lonnqvist, Wahlbeck, Klaukka, Niskanen and Tanskanen49 In female patients with schizophrenia, prolactin and antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinaemia have been hypothesised to play a role in the development and progression of breast cancer, but available evidence remains controversial and inconclusive. Reference De Hert, Peuskens, Sabbe, Mitchell, Stubbs and Neven50–Reference De Hert, Vancampfort, Stubbs, Sabbe, Wildiers and Detraux52

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of this study is the use of a systematic approach to identify and analyse available evidence. Additionally, the inclusion of data from a large number of identified studies ensures a robust pooled estimate with a high statistical power. There appears to be a high validity of death status and causes of death in the included studies. Information on death status and causes in all the included studies was ascertained from well-established general death registries (such as the National Death Index in the USA and Swedish Death Registry), specific registries of cause of death (for example Danish Register of Causes of Death and Finnish National Causes of Death Register) or directly from national or local death certificates. Death certificates and other official documents were referred to in order to establish the causes of death in all those death registries. Furthermore, there was evidence indicating that the causes of death on death certificates in patients with schizophrenia were probably more accurate than in the general population, because rates of post-mortem examination (54% v. 22%) and coroner's inquest (15% v. 6%) were higher than the national average. Reference Brown, Kim, Mitchell and Inskip10

There are also several limitations. First, the use of SMRs in most previous studies may underestimate the true risk of cancer mortality in patients with schizophrenia, because in calculating SMRs, the comparator group is usually the general population, which is comprised of individuals with and without schizophrenia. As shown in previous methodological papers, Reference Jones and Swerdlow53,Reference Card, Solaymani-Dodaran, Hubbard, Logan and West54 this bias was obvious when the risk was assessed in cohort studies of people with common diseases or exposures and/or when large SMRs were observed. However, because the prevalence of schizophrenia is low (~1%) in the general population and the observed SMRs for cancer mortality after a diagnosis of schizophrenia in most studies were modest, the underestimation of true risk by SMRs in the current scenario would be minor. Reference Jones and Swerdlow53,Reference Card, Solaymani-Dodaran, Hubbard, Logan and West54 In this meta-analysis, such concerns were further reduced because we presented not only the pooled SMRs, but also the pooled HRs, which appeared to be stronger than the pooled SMRs. Second, the risk of cancer mortality by specific types/sites (i.e. lung cancer, breast cancer, etc.) was not summarised in this study because a possible selective reporting bias was observed for the risk of mortality from certain types of cancer in previous studies. In addition to the risk of overall cancer mortality, many studies simply chose to report significant findings for certain types of cancer. Some other studies may be unable to derive a risk estimate for certain types of cancer because the sample size was too small. Apparently, pooling the results from those studies will lead to a biased estimation. In the large study by Olfson et al Reference Olfson, Gerhard, Huang, Crystal and Stroup9 increased mortality was consistently observed in all cancer subtypes (i.e. lung, colon, breast, liver, pancreas, haematological), with nearly identical SMRs in men and women. This indicates that variations in the risk of mortality from different types of cancer may not be substantial. Further investigation on this is warranted in future studies. Third, information on antipsychotic medication and smoking status was not available in most studies. Whether these factors moderate or mediate the association between schizophrenia and cancer mortality needs further investigation.

Implications

This study has important clinical implications. Because of the high social and economic burden associated with schizophrenia, Reference Chong, Teoh, Wu, Kotirum, Chiou and Chaiyakunapruk2 it is important to clearly understand schizophrenia-related clinical outcomes such as morbidity and mortality risk. Findings from our study emphasise the need for clinicians to be aware of the increased risk of cancer mortality in people with schizophrenia. It appears to be imperative to address health disparities and improve cancer survival among patients with schizophrenia through an integrated approach, which may involve an improvement in access and quality of care, early cancer screening and diagnosis, as well as smoking cessation services.

In conclusion, this systematic review and meta-analysis found a significantly increased risk of cancer mortality in patients with schizophrenia. Future cohort studies with a large sample size and long follow-up are warranted to confirm our findings and to elucidate the risk of mortality from specific types/sites of cancers.

Funding

This work was supported by Found of Tianjin Health Bureau ( to C.Z.), Chinese Postdoctoral Science Foundation ( to C.Z.), Jiangsu Haosen pharmaceutical Limited by Share Ltd (2016-Young scholar support project to C.Z.), Hainan Liou pharmaceutical Limited by Share Ltd (2016-Young scholar support project to C.Z.), Xuzhou Enhua pharmaceutical Limited by Share Ltd (2016-Young scholar support project to C.Z.), Shanghai Zhongxi pharmaceutical Limited by Share Ltd (2016-Young scholar support project to C.Z.).

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.