INTRODUCTION

Business entertainment refers to entertainment events hosted in business settings. The formats of these entertainment activities include banquets, social drinking, gift-giving, golfing, watching sports games, traveling, etc. (Bruhn, Reference Bruhn1996; Hite & Bellizzi, Reference Hite and Bellizzi1987; Kavali, Tzokas, & Saren, Reference Kavali, Tzokas and Saren2001; Yang, Reference Yang2002). Some of those activities are general and routine etiquettes that serve to foster good business relationships. There are also entertainment activities that are used to distort buying or selling decisions in a related transaction, especially in certain settings that also involve government officials. This type of business entertainment is considered corruption and prohibited in most societies (Manion, Reference Manion1996; Mauro, Reference Mauro1995; McCubbins, Reference McCubbins2001; The New York Times, 2014). In this study, we focus only on voluntary and non-corruptive entertainment events that serve to nourish business relationships between private managers.

Entertainment activities in private business settings are widely observable all over the world. In China, for instance, managers often entertain each other at venues including restaurants, karaoke lounges, bowling alleys, sauna rooms, hair studios, and massage parlors (Zhang, Reference Zhang and Hodgson2001). Likewise, business managers in Japan routinely entertain in nightclubs at the company's expense (Allison, Reference Allison1994). A survey in Greece indicates that most managers there see extravagant banqueting and lavish gift-giving in business settings as acceptable customs (Kavali et al., Reference Kavali, Tzokas and Saren2001). Australian and Canadian executives also see entertaining and gift-giving as common business practices in their societies (Chan & Armstrong, Reference Chan and Armstrong1999).

The prevalence of business entertainment has attracted attention from management researchers, whose views can be roughly classified as positive or negative. Those who take a positive view have identified an instrumental role for entertainment activities to play in facilitating business transactions (Beck & Maher, Reference Beck and Maher1986; Beltramini, Reference Beltramini1992; Dorsch & Kelly, Reference Dorsch and Kelly1994). This positive view sees business entertainment as a relationship-building practice in which gifts and favors can be used to promote sales (Bruhn, Reference Bruhn1996; Hite & Bellizzi, Reference Hite and Bellizzi1987). A constructive role of business entertainment can also be found in research on business guanxi (Gold, Guthrie, & Wank, Reference Gold, Guthrie, Wank, Gold, Guthrie and Wank2002; Yang, Reference Yang1994). Guanxi researchers propose that business connections built through entertainment events serve to supplement formal institutional support (Xin & Pearce, Reference Xin and Pearce1996), which improves business efficiency and thereby justifies the expenses on business entertainment (see e.g., Chen, Huang, & Sternquist, Reference Chen, Huang and Sternquist2011; Davies, Leung, Luk, & Wong, Reference Davies, Leung, Luk and Wong1995; Yeung & Tung, Reference Yeung and Tung1996).

Yet, the role of business entertainment in facilitating transactional relationships seems anecdotal in the literature. We still do not know the mechanism whereby business entertainment plays such a role. The lack of a systematic account for this facilitating role, thus, raises our first research question: does business entertainment really play any role in facilitating economic exchanges?

There are also scholars who take a negative perspective to analyze business entertainment with a social approach that addresses its ethical concerns normatively (Fritzsche, Reference Fritzsche2005; Mellahi & Wood, Reference Mellahi and Wood2003). These negative views of business entertainment are built on the premise that entertainment activities are equivalent to bribery, which is usually considered a synonym for corruption (Getz, Reference Getz2006). Some guanxi researchers also believe that entertainment-related practices can trigger ethical problems (Fan, Reference Fan2002), jeopardize corporate governance, and hamper economic development (Braendle, Gasser, & Noll, Reference Braendle, Gasser and Noll2005). An outright negative view of business entertainment might be valid if government officials are the guests at entertainment events, but it does not always hold in private business settings that involve a host and a guest. It is easy to understand a host's attempt to corrupt a guest's decision, but it is harder to explain why a guest would willingly participate in an entertainment event that is designed to ‘corrupt’ him/her. One intuitive explanation is that guest managers seek personal benefits from such events at their company's expense. Previous studies, nevertheless, have found that this agency issue is not significant in business entertainment because both hosts and guests are often owner-managers themselves (Cai, Fang, & Xu, Reference Cai, Fang and Xu2011). Another explanation in international settings is that a foreign guest might expect to split the bill prior to attending an entertainment event, but the local host ends up paying all expenses as normally seen in some countries (e.g., China; see Sun, Reference Sun2016).Footnote [1]

By common sense, therefore, business managers should refuse to attend any entertainment event unless it can create a win-win outcome for the parties involved. Previously, however, the necessity for the win-win outcome of business entertainment has not been specified in the literature, which leads to our second research question: if business entertainment is truly corruptive, why do guest managers not avoid an entertainment event?

Further, although business entertainment is a popular social practice worldwide, we also observe wide variations in its popularity and legitimacy across countries. China and Japan, for instance, have both legitimized entertainment expenses as an accounting item for tax returns. According to the annual reports of over 200 companies listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange, these firms spent more than 10 percent of their net profits on business entertainment in 2007 (Shanghai Stock Exchange, 2009). In 2008 alone, entertainment expenses for corporate Japan totaled US$32 billion (National Tax Agency of Japan, 2012). Business entertainment, although still observable in the US, is practiced at an extent or on a scale that is much smaller than what is seen in Asia.

While business entertainment has attracted substantial research attention, prior studies tend to see it as a corruptive social practice plaguing emerging markets. The presence of business entertainment in all societies and the wide variation in its popularity and legitimacy across countries, therefore, prompt our third question: Why is business entertainment more prevalent in some societies than in others?

The purpose of this study is to answer these three questions and advance our understanding of business entertainment. We take an institutional approach to justify the persistence of business entertainment in economic exchanges, where entertainment in private business settings can boost the power of social sanctions in governing economic transactions. This approach offers a systematic account of the positive role of business entertainment in facilitating exchange relationships. Thanks to this governance role, business entertainment can create a win-win outcome for the parties involved. This governance role can further predict the prevalence of business entertainment across societies that differ in their reliance on social sanctions to govern economic exchanges.

In the following pages, we first review the governance structures for economic exchanges that cover market, legal, and social sanctions. We further explain how business entertainment serves to reinforce the power of social sanctions in regulating the behaviors of economic actors, particularly under the conditions where market and legal infrastructures are underdeveloped. Based on a relativity model of transaction governance, we extend this institutional view to draw a set of propositions that can predict the prevalence of business entertainment across societies. Finally, we conclude the paper by outlining its scholarly and practical implications.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

In this section, we review the governance structures for economic exchanges that consist of market, legal, and social sanctions.Footnote [2] In particular, we outline three conditions under which social sanctions work more effectively to regulate economic exchanges. Under the three conditions, as further argued in this section, business entertainment plays a positive role to enhance the power of social sanctions in regulating the behavior of economic actors.

The Governance Structures for Economic Exchanges

The governance of economic exchanges involves two key issues: the efficient allocation of resources and the fair distribution of output gains (Greif, Reference Greif2000). All economic actors are either induced or coerced to comply with the guidelines commonly accepted in a society, which thereafter resolves the above two governance issues in economic exchanges (Coase, Reference Coase1992; Williamson, Reference Williamson1979). Such commonly accepted guidelines include market rules, legal restraints, and social norms, which are also defined as market, legal, and social sanctions (Sun, Reference Sun2012).

Market sanctions

The ‘ideal’ economic exchanges are price-induced and voluntary in nature, wherein economic actors transact with each other based on their utility preferences (Hayek, Reference Hayek1945). Under a perfect price system, the parties involved in any market transaction remain faceless and respond only to price signals in maximizing their gains (Arrow, Reference Arrow1974). If sellers are satisfied with the market price of a product, they will increase their output to serve more customers. Likewise, if buyers are happy with the value of a product at the market price, they will reward sellers by granting more trading opportunities. In cases wherein the outcome of a market transaction fails to meet their expectation, the parties involved can penalize each other by pulling out of the exchange relationship. Thus, the market system has the power to guide the behaviors of economic actors, a control mechanism that is called ‘market sanctions’.

Economic reality, however, often deviates from the classical assumptions of free entry and free exit under a perfect price system (Grossman & Stiglitz, Reference Grossman and Stiglitz1976). Presumably, free entry is nonexistent in some industrial sectors that are bound by technological and reputation-based barriers (Caves & Porter, Reference Caves and Porter1977). In addition, free exit is difficult owing to the presence of specific assets that creates the holdup problem and thereby limits market breadth (Williamson, Reference Williamson1985). Moreover, prices do not always reflect the true value of goods and services, which provides imperfect information for economic actors to optimize their decisions (Barzel, Reference Barzel1982). Inevitably, these factors that impair the self-enforcing power of voluntary transactions will cause market sanctions to fail in regulating the behaviors of economic actors (Arrow, Reference Arrow and Intriligator1971).

Legal sanctions

In cases that the price system fails to coordinate economic exchanges, non-market institutions will emerge to correct for market imperfections. Legal sanctions are the standard institutional antidote that can supplement or even substitute for market sanctions in governing economic exchanges (Macneil, Reference Macneil1978). In an exchange relationship upheld by legal infrastructures, the rights and obligations of the parties to the relationship are often explicitly stipulated and strictly enforced. Those who fail to follow the contract are subjected to legal penalties inflicted by a third-party enforcer, i.e., the State.

Legal sanctions can facilitate impersonal exchanges where the decision to transact is not based on knowing the value of a product on the spot or on expecting more trading opportunities upon confirmation of its true value afterwards. Legal sanctions optimize the economic welfare of a society by barring undue gains or losses resulting from deficient market sanctions (Glaeser & Shleifer, Reference Glaeser and Shleifer2002). Yet, legal restraints specified in contracts are usually unable to foresee all contingencies, which means that the parties to an exchange relationship must incur extra costs to negotiate a complete contract or enforce an incomplete one. More importantly, the costs incurred collectively by a society to set up the legal framework could be extremely high. These limitations suggest that legal sanctions are not always the ultimate solution to market imperfections (Williamson, Reference Williamson1985).

Social sanctions

The distinction between market and legal sanctions constitutes the basis of traditional transaction costs economics (TCE), which frames the governance of economic exchanges along the market – contract – hierarchy continuum (Williamson, Reference Williamson1979). This market – contract paradigm has drawn criticism for neglecting the force of social sanctions in regulating exchange relationships (Demsetz, Reference Demsetz1988). In fact, social sanctions have been a primitive governance device for economic exchanges long before the emergence of the market system (Benson, Reference Benson1999). While legal sanctions serve as a formal institutional remedy to market failure, social sanctions work as an informal institutional supplement to market power in facilitating economic exchanges (North, Reference North1994).

Social sanctions represent a social and psychological process through which behavioral norms are established and enforced at the individual and the society levels. At the individual level, all members of a society are raised to internalize the behavioral norms established in the society. Observing the internalized norms can make them feel happy and satisfied psychologically, whereas violating the norms can produce self-punitive emotions such as guilt and shame (Cooter, 1988; McAdams, Reference McAdams1996). At the society level, the members of a group are expected to enforce the norms in social and economic exchanges by rewarding conformers or punishing deviators along with those who refuse to enforce such norms (Posner, Reference Posner1997). In economic exchanges, particularly, social sanctions can curb opportunistic behaviors to harmonize the mutual interests of trading partners (Cooter, Reference Cooter1998; Ouchi, Reference Ouchi1980). Even in those societies that rely predominantly on legal sanctions to mitigate market inefficiencies, social sanctions still play a role in regulating the behaviors of economic actors (Macaulay, Reference Macaulay1963).

Conditions for Social Sanctions to Support Economic Exchanges

The use of social sanctions to support economic exchanges requires three pre-conditions. First, the parties to an exchange relationship must follow the norm of reciprocity. Second, for the norm of reciprocity to work, the parties to the transaction must maintain a long-term relationship. Third, economic exchanges must be conducted in a communal setting that observes the norm of reciprocity and nurtures interpersonal relationships collectively.

The norm of reciprocity

Based on the concept of fairness, the norm of reciprocity is the primary rule to regulate interpersonal interactions, including the seller-buyer relationship in economic exchanges (Chen, Reference Chen2010; Fehr, Gachter, & Kirchsteiger, Reference Fehr, Gachter and Kirchsteiger1997). In an arm's length market transaction, the price of a product should equal its true value based on the rule of exact price settlement. In a social exchange, however, the norm of approximate goodwill reciprocity dictates that the price can be approximate to the true value of a product. By following the norm of approximate goodwill reciprocity, the parties to an economic exchange do not need to settle the transaction on the spot as required by the rule of exact price settlement.

In those societies where the norm of reciprocity is widely observed and strictly enforced, social sanctions work best to support market sanctions in regulating the behaviors of economic actors. At the personal level, confirming to this norm can make an individual greatly joyful and failing to do so is more likely to result in self-imposed emotional penalties. The members of such a society are more likely to earn respect and good reputation by following the norm of reciprocity, but face peer disapproval and social ostracism by violating this norm (Noussair & Tucker, Reference Noussair and Tucker2005). Such personal and group penalties represent social sanctions that force economic actors to abide by transaction terms even in the face of material losses. Observing the norm of reciprocity, therefore, is the primary condition for social sanctions to work in governing economic exchanges.

Long-term relationship

In a market transaction supported by the rule of exact price exchange, the parties involved could be two strangers who settle the transaction on the spot. In a social exchange guided by the norm of approximate goodwill reciprocity, the parties still have to settle the exchange, although not on the spot. Instead, the parties can build and maintain a long-term relationship wherein the goodwill received at one point in time will be reciprocated at another. Because the goodwill reciprocated is often approximate, the favor and debt might not be balanced even after repeated transactions, suggesting that a long-term orientation is absolutely necessary for supporting any on-going interpersonal relationship built on the norm of goodwill reciprocity.

A long-term relationship between the parties involved is, thus, another necessary condition for social sanctions to work in regulating the behaviors of economic actors. In fact, the purpose of all networking practices, including the Chinese guanxi, is to build long-term relationships whereby one can ask a favor from the other with the expectation that the debt will be repaid in the future (Yang, Reference Yang1994). A guanxi network's eventual success is strictly keyed to a long-term perspective that allows guanxi-based transactions to be repeated (Alston, Reference Alston1989; Lee & Dawes, Reference Lee and Dawes2005). In such repeated transactions, both the seller and the buyer understand that honest behaviors will be rewarded but cheating behaviors penalized in the future. Such expected rewards or punishments in future transactions constitute social sanctions to deter opportunistic behavior in current transactions. Consequently, social sanctions work more effectively in inducing cooperation and deterring opportunism when the parties to an economic exchange maintain a long-term relationship.

Communal setting

A third condition for social sanctions to work in regulating the behaviors of economic actors is that the parties to an exchange relationship live in a communal setting that provides the context for the establishment and enforcement of behavioral norms, including the norm of reciprocity. Through collective teaching and socialization, group living allows the members of a community to internalize the norm of reciprocity (Coleman, Reference Coleman1990). A communal setting is also necessary for all group members to observe the same set of behavioral norms. Particularly, group living makes it easier to expose norm violators to other members of the community, who can then serve as the enforcers of social sanctions in supporting economic exchanges (Posner, Reference Posner1997). Furthermore, a communal setting enables frequent interactions among its members and helps them to develop long-term relationships, which also facilitates the establishment and enforcement of behavioral norms (Axelrod, Reference Axelrod1984). A communal setting, thus, is necessary for social sanctions to work in regulating exchange relationships, be they economic or social.

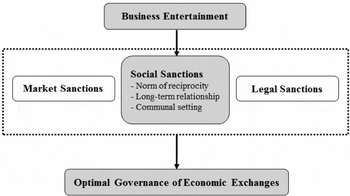

Business Entertainment Boosts the Governance Power of Social Sanctions

As noted above, social sanctions serve to govern economic exchanges under three conditions: the norm of reciprocity, a long-term orientation, and a communal setting. We will further demonstrate that business entertainment can strengthen the governance power of social sanctions by improving the above three conditions. More precisely, business entertainment plays a governance role by supporting the norm of reciprocity, building long-term relationships, and weaving communal networks, which allows social sanctions to work more effectively as a supplement or substitute to legal sanctions in correcting for the weakness of market sanctions (see Figure 1 for how business entertainment works to play such a role in the optimal governance of economic exchanges).

Figure 1. Business entertainment, social sanctions, & optimal governance of economic exchanges

Business entertainment supports the norm of reciprocity

We have noted that observing the norm of reciprocity is the primary condition for social sanctions to work in resolving the issue of market failure. In an economic transaction, market failure manifests itself in a manner that the price of the focal product departs from its true value (Barzel, Reference Barzel1982). Such price-value gaps can be eliminated through contingent pricing, meaning that the price of a product is tied to particular contractual contingencies backed up with legal sanctions. Yet, a complete contract that covers all potential contingents is difficult and hence costly to negotiate and enforce (Williamson, Reference Williamson1985). In cases where legal sanctions have failed to correct for the failure of market sanctions, business entertainment can kick in to boost the power of social sanctions by supporting the norm of reciprocity, both directly and indirectly.

As a form of social exchange, business entertainment initiates a material transfer whereby goodwill flows from one party to the other (for a discussion of material and goodwill flow in social exchanges, see Blau, Reference Blau1964). The material dimension of business entertainment serves directly as an action of reciprocity to settle the accompanied transaction. If the true value of a product turns out to be lower than its market price, for instance, business entertainment can kick in as a social exchange to balance the price-value gap, where the party who enjoys a gain can reciprocate the other who incurs a loss with an entertainment event. Built on the norm of reciprocity, the material flow in business entertainment can directly offset the price-value gap in the accompanied economic transaction.

Business entertainment can also support the norm of reciprocity indirectly to reinforce the power of social sanctions in governing an exchange relationship. The goodwill arising from an entertainment event can function as a tie that links the host and the guest by holding them accountable to each other (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1967). By agreeing to attend an entertainment event, the guest accepts the goodwill and ‘a portion of the being’ from the host, as happens in all gift exchanges (see e.g., Sherry Jr., Reference Sherry1983: 159). If the guest fails to return the goodwill in the accompanied transaction, he/she would incur internal emotional penalties and external group sanctions (Noussair & Tucker, Reference Noussair and Tucker2005). Indirectly, those social interactions afforded by entertainment events can increase a guest's commitment to the accompanied transaction in fulfilling his/her obligations to the host under the norm of reciprocity (Greenberg, Reference Greenberg, Gergen, Greenberg and Willis1980).

Business entertainment builds long-term relationships

The working of social sanctions in supporting economic transactions requires the parties to establish and maintain a long-term relationship. Business entertainment is a powerful tool that builds and keeps long-term relationships through a process of emotional and material exchanges (for a discussion of the features of social exhanges, see Foa and Foa, Reference Foa, Foa, Gergen, Greenberg and Willis1980). On the emotional side, entertainment activities facilitate long-term interactions by mobilizing egoistic motivations and transferring them into the maintenance of the social relationship (see Gouldner, Reference Gouldner1960). Here, egoism can motivate the host to satisfy the expectation of the guest so as to induce the guest to reciprocate and thereby satisfy the host's expectation. Once a stable cycle of mutual gratification has been established, this process becomes self-perpetuating, such that business entertainment serves as a starting device and a stabilizing mechanism for the parties to build and keep a long-term relationship.

On the material side, the guest in an entertainment event owes a favor to the host as in other types of social exchanges (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1967). However, the favor to be reciprocated is approximate and therefore cannot be accurately measured. In some cases, the payback falls short of the original favor, thus requiring a second act by the guest to return the remaining goodwill to the host. In other cases, the payback exceeds the favor received, putting the original host in an indebted position to the guest instead (Blau, Reference Blau1964). Such a constant imbalance in goodwill reciprocity results in repeated interactions that help the parties involved maintain a long-term relationship (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1967; Simmel, 1908/Reference Simmel and Wolff1950). The very same rule is necessary for building guanxi relationships in China, as reflected in its traditional norm that ‘the receipt of a droplet of generosity should be repaid with a gushing spring’.

Thus, business entertainment builds and sustains long-term relationships through two mechanisms. First, it initiates and sustains social interactions between the parties to a market transaction who develop stronger commitments to one another as if bound by a contract. Second, it facilitates repeated interactions between two trading partners by creating an imbalance in goodwill that can only be cancelled out over the long term. Similar to guanxi practices that enhance the long-term viability of social relationships (Park & Luo, Reference Park and Luo2001), business entertainment helps to build long-term relationships and thereby boosts the power of social sanctions in regulating the behaviors of economic actors.

Business entertainment weaves communal networks

Social sanctions work to regulate the behaviors of economic actors only when they reside in a communal setting. Business entertainment helps to weave such communal settings that establish and enforce social norms at the collective level. Business entertainment constitutes a dyadic interaction that involves a host and a guest (i.e., the seller and the buyer in the accompanied transaction). Usually, the parties switch positions in subsequent transactions or enter new exchange relationships with other community members, such that strangers turn into acquaintances and outsiders into insiders. Eventually, a larger web of overlapped transactional dyads emerges to create the communal network that is required for social sanctions to work in regulating economic exchanges. For instance, the aim of Chinese guanxi practices is to build flexible but relatively stable communal networks, where trust and reputation enable transactions to occur without opportunistic gains, which in turn lowers the costs of market transactions (Lovett, Simmons, & Kali, Reference Lovett, Simmons and Kali1999).

Further, frequent entertainment events in business settings increase the physical proximity between the parties to a market transaction and expose their behaviors to common acquaintances. Such exposures make it easier for the members of a community to monitor one another and, if necessary, to penalize one another for violating the social norms that they observe collectively. If an individual has failed to follow the norm of reciprocity, for instance, the notoriety of his/her untrustworthiness and non-cooperativeness would spread in the community. As a result, the defaulter would have fewer exchange opportunities due to the collective penalties imposed by other members of the community, ranging from exclusion, rejection, to ostracism (Baumeister & Leary, Reference Baumeister and Leary1995).

Business entertainment, hence, can help weave a communal setting wherein behavioral norms are internalized at the individual level and enforced at the collective level. By increasing the visibility of an exchange relationship in such a communal setting, business entertainment renders the deviant behaviors of the parties involved harder to hide but easier to monitor (Festinger, Schachter, & Back, Reference Festinger, Schachter and Back1963). This is another way that business entertainment works to reinforce the power of social sanctions in regulating an economic exchange that market and legal sanctions have both failed to support.

In sum, economic exchanges can be governed through market, legal, and social sanctions, where social sanctions work more effectively to regulate exchange relationships if the parties involved observe the norm of reciprocity, maintain a long-term relationship, and reside in a communal setting. As a form of social exchange, business entertainment can strengthen the three conditions under which social sanctions work to support market transactions, as depicted in Figure 1 earlier. Thus, business entertainment plays a governance role to enhance the power of social sanctions in regulating the behaviors of economic actors. Thanks to this governance role, business entertainment can lead to a win-win outcome for the parties to an economic exchange that market and legal sanctions have both failed to support.

PERVASIVENESS OF BUSINESS ENTERTAINMENT ACROSS SOCIETIES

Our analyses have thus far answered two of the three research questions raised earlier in this paper: Does business entertainment play a role in facilitating economic exchanges and, if yes, how does it play this role? In the next section, we build a relativity model of transaction governance and use it to draw a set of propositions that can predict the prevalence of business entertainment in each society. These propositions can answer our third research question: Why is business entertainment prevalent in one society but scarce in another?

The Relativity Model of Transaction Governance

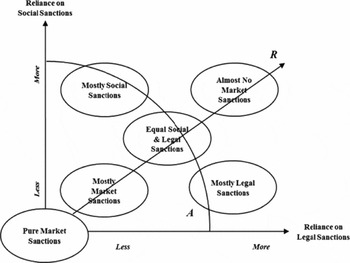

As proposed by economic sociologists (e.g., Polanyi, 1944/Reference Polanyi2001), all exchange relationships are embedded in a web of individual motivations (market sanctions), state regulations (legal sanctions), and societal norms (social sanctions). Hence, market, legal, and social sanctions are not mutually exclusive, but can be combined in numerous manners to regulate the behaviors of economic actors (Zelizer, Reference Zelizer1988). Under the condition of weak market power, for instance, social sanctions make it possible for the members of a community to trade without resorting to lengthy contracts (Fehr & Gachter, Reference Fehr and Gachter2000). Or, legal sanctions allow the members of a community to conduct long-distance trade with outsiders who do not abide by the same set of social norms. In other words, social and legal sanctions can be used concurrently to correct for the imperfections of market sanctions in governing economic exchanges. Depending on different cultural and historical heritages, each society can collectively adopt a unique combination of market, legal, and social sanctions to facilitate economic exchanges (see e.g., Biggart & Delbridge, Reference Biggart and Delbridge2004; Bradach & Eccles, Reference Bradach and Eccles1989; Hamilton & Biggart, Reference Hamilton and Biggart1988; Lindberg, Campbell, & Hollingsworth, Reference Lindberg, Campbell, Hollingsworth, Campbell, Hollingsworth and Lindberg1991). We call such a combination the transaction governance structure (TGS).

Building on the TGS framework, we propose a relativity model such that each society will adopt a TGS that relies on a unique combination of social and legal sanctions to supplement market sanctions in regulating the behaviors of economic actors. This relativity model is depicted in a two-dimensional space in Figure 2, where the x-axis measures a society's degree of reliance on legal sanctions, and the y-axis its reliance on social sanctions, to correct for the weakness of market sanctions. The origin of the space, thus, represents the use of pure market sanctions to facilitate economic exchanges, which implies that neither legal sanctions nor social sanctions are needed for supporting a perfect market, a hypothetical condition that does not exist in the real world.

Figure 2. Relativity of transaction governance

The oval at the upper-right corner of the space represents an extremely imperfect market, where a society uses almost no market sanctions to govern economic exchanges. Instead, this society relies mainly on social and legal sanctions to govern economic activities, another rare condition similar to a command economy that uses absolute state power and strong social norms to support economic transactions. The oval near the origin denotes a society that uses mostly market sanctions to regulate economic exchanges, thus relying little on social and legal sanctions to support a nearly perfect market.

Clearly, the distance from the origin to any point in the space measures the degree of market failure. As illustrated by Ray R, the longer the distance between the origin and the point that denotes a society, the higher the level of market failure in this society. As such, all points on Arc A that are equally distant from the origin denote all of the societies that experience the same level of market failure. Under this level of market inefficiency captured by Arc A, social and legal sanctions can be used in numerous combinations to supplement market sanctions. The oval at the upper end of Arc A, for instance, stands for a society that uses mostly social sanctions to supplement market sanctions. In contrast, the oval at the lower end of Arc A represents a society that uses mostly legal sanctions to remedy market failure. Finally, the oval in the middle of Arc A depicts a society that relies equally on social and legal sanctions to resolve the same level of market imperfection.

Every society can find a spot in this space that represents the type of TGS that it uses to govern economic exchanges. A society's position in this space can justify the prevalence or scarcity of business entertainment in the society as a booster of social sanctions to supplement market and legal sanctions. Specifically, business entertainment should be more pervasive in those societies where social sanctions play a greater role, but legal sanctions a lesser role, to correct for the weakness of market sanctions.

Business Entertainment Pervasiveness Across Societies

Based on a society's relative reliance on social versus legal sanctions as a supplement to market sanctions, we draw a set of propositions to highlight the governance role of business entertainment and thereafter predict its popularity and legitimacy in the society.Footnote [3] More precisely, the governance role of business entertainment will be more prominent, and thus entertainment activities more popular, in those societies with underdeveloped market and legal infrastructures, but with dense social fabrics.

Market infrastructures

The relativity model of transaction governance indicates that the power of market sanctions differs across societies. Strong market power can be seen in those societies with well-developed market infrastructures, such as clearly defined property rights, a greater number of buyers and sellers, lower entry and exit barriers, better information flow, and so on. In such societies, market sanctions are effective enough to govern most economic exchanges, where business entertainment is used less often to reinforce the power of social sanctions in addressing the issue of market failure.

The US provides an excellent example of an economy with strong market rules that can be traced back to two traditions. First, the US started as an immigrant society with a small population as well as a homogenous economic base (Parsons, Reference Parsons2007). In the early years of colonization, this society lacked trade opportunities internally and was forced to develop a market system that could support long-distance trade with homelands and other societies (Engerman & Sokoloff, Reference Engerman and Sokoloff2008). Second, the US society inherited an individualistic culture from ascetic Protestantism and the liberal tradition of the Enlightenment (Parsons, Reference Parsons2007). Under an individualistic culture, economic transactions are price-based and impersonal, in that all exchange partners are treated as equals regardless of their status as insiders or outsiders (Greif, Reference Greif1994). The joint influence of these two traditions in the US allows most economic exchanges to be guided through market rules, where sellers and buyers are driven more by self-interest and less by social relations. Strong market rules reduce the reliance of the US society on social sanctions to govern economic transactions. As a result, less business entertainment is required to reinforce the power of social sanctions in regulating the behaviors of economic actors in the US.

There are also societies that feature poor market infrastructures, such as ill-defined property rights, less competition due to small numbers of sellers and buyers, and the absence of relevant institutions that can facilitate trade. In these societies, market rules are not strong enough to facilitate economic decisions regarding what to produce, how much to produce, where to trade, et cetera. Irrespective of the legal framework that can be deployed to enforce formal contracts, poor market infrastructures increase a society's reliance on social sanctions to regulate the behaviors of economic actors. Consequently, business entertainment is used more extensively to reinforce the power of social sanctions in supporting economic exchanges.

The pre-reform era in China constitutes a great example of underdeveloped market infrastructures. The traditional Chinese society featured an immature market because of the support for agriculture and suppression of commerce by most dynasties (Balazs, Reference Balazs1965). In China, historically, labor was fettered to the land, output was consumed locally with limited trade with outsiders, and capital was reinvested into the land with little accumulation or circulation (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton and Hamilton2006b). Although dynasties came and went, the society followed the trajectory of an agricultural economy with an autarky system that remained largely unchanged for hundreds of years (Fei, Reference Fei1939). Until the late 1800s, the Qing Dynasty continued to resist commerce with the outside world, even under the threat of war (Keller, Li, & Shiue, Reference Keller, Li and Shiue2011). As a result, China kept an economic system that was tightly integrated with the rest of social life (Hamilton, Reference Hamilton and Hamilton2006a). The embedment of economic activities in social fabrics was further reinvigorated by the collectivist culture in China, where economic actors trade with one another within a social group like the guanxi networks (Park & Luo, Reference Park and Luo2001), and exchange relations are an integral part of the whole web of kinships and friendships (Fried, Reference Fried1953). This collectivist culture impeded the development of impersonal governance devices such as market sanctions to support discrete and long-distance trade with the outside world (North & Weingast, Reference North and Weingast1989).

Based on the relativity model of transaction governance, underdeveloped market infrastructures in a society must be supplemented by a combination of legal and social sanctions to facilitate economic exchanges. The less developed the market infrastructures in a society, the greater the role played by social sanctions to remedy market imperfection, with the society's reliance on legal sanctions kept constant. This is why business entertainment is limited in the US but notoriously rampant in China. All else being equal, social sanctions must play a greater role in facilitating economic exchanges in those societies that feature underdeveloped market infrastructures, meaning that business entertainment should be used more widely to reinforce the power of social sanctions in regulating the behaviors of economic actors. Hence,

Proposition 1: Business entertainment will be more prevalent in those societies featuring poor market infrastructures, ceteris paribus.

Legal infrastructures

According to the relativity model of transaction governance, social and legal sanctions can be used in numerous combinations to supplement market sanctions in governing economic exchanges. The reliance of a society on social versus legal sanctions to correct for a given level of market inefficiency hinges on the relative effectiveness of these two governance devices in the society. Legal sanctions will be used more intensively in those institutional contexts where legal infrastructures are well developed. In such cases, social sanctions will play a smaller role in facilitating economic exchanges. Hence, business entertainment will be used less widely to reinforce social sanctions to correct for the weakness of market sanctions. Clearly, the availability of legal infrastructures in a society can also predict the prevalence of business entertainment in this society.

The development of legal infrastructures varies substantially across countries. The Chinese society, for instance, has traditionally been characterized by the rule of norm rather than the rule of law (Portes & Haller, Reference Portes, Haller, Smelser and Swedberg2005). The absence of well-developed legal systems could be attributed to the Confucian values that became the official doctrine during the Han dynasty (201 B.C–220 A.D.). In Confucian teachings, the Chinese emperors served more as the promoter of social norms and personal virtues, than as the rule maker and enforcer (Balazs, Reference Balazs1965). Even after the fall of the Qing dynasty, neither the nationalists nor the communists made much progress in creating a legal system out of the Confucian tradition of rule by norms (Potter, Reference Potter, Gold, Guthrie and Wank2002). One key reason is that intertwined personal relationships like guanxi in China's collective society made impartial enforcement of laws difficult. Even though China has renewed efforts to build a modern court system, legal sanctions still play a rather limited role in regulating the behaviors of economic actors. The absence of well-developed legal infrastructures led China to a TGS that relies more on social sanctions to remedy the imperfection of market sanctions. Hence, business entertainment is used more widely to boost the power of social sanctions in China.

Japan is a good contrast to China in terms of legal infrastructures. Like China, traditional Japanese society also followed the Confucian value without a strong legal system. Yet, two forces in recent history broke Japan away from the institutional trajectory of China. The first was the Meiji Restoration in 1868, wherein Japan emulated Western societies by introducing a series of legal, political, military, economic, and educational reforms (Westney, Reference Westney1982). The industrialization agenda during that period also increased the diversity and complexity of economic transactions that social norms alone could not support and thus required the governance of legal restraints. Indeed, one major achievement in the Meiji Restoration was the creation of a legal system to complement, but not replace, the rule of norm in Japan (Hunter, Reference Hunter, Blomstrom and La-Croix2005).

The second force that distinguished Japan from China in the development of legal infrastructures was the US-led Allied Occupation after World War II. During that period, Japan initiated constitutional reforms to weaken the monarch's power and install a democratic political system (Upham, Reference Upham1987). Modern civil and criminal codes were compiled and court systems were established on the beliefs and traditions of Western democratic countries. The legal profession in Japan was redesigned to imitate Anglo-American traditions (Oppler, Reference Oppler1976), which allowed legal sanctions to be used concurrently with social sanctions to support market sanctions in transaction governance (Yafeh, Reference Yafeh2000).

Those two forces allowed Japan to modernize legal infrastructures to complement the collectivist tradition of rule by norm. Relative to China, the Japanese society relies less on social sanctions, but more on legal sanctions, as a remedy to the weakness of market sanctions in transaction governance. In Japan, therefore, business entertainment now plays a diminishing role in boosting the power of social sanctions to regulate the behaviors of economic actors. The cutbacks on entertaining budget among Japanese firms have harmed the service sector badly enough to cause government concern. In 2013, for instance, the Japanese government granted major tax incentives to encourage corporate entertainment spending as a way to revitalize the service sector (The Economist, 2013).Footnote [4]

To correct for the same level of market failure, as illustrated in our relativity model of transaction governance, social and legal sanctions can be used in numerous combinations to remedy the weakness of market sanctions, wherein a greater role played by legal sanctions in transaction governance will decrease the role of social sanctions. All else being equal, business entertainment will be used less widely to boost the governance power of social sanctions in those societies with better-developed legal infrastructures. Hence,

Proposition 2: Business entertainment will be less prevalent in those societies featuring better developed legal infrastructures, ceteris paribus.

Social fabrics

As noted earlier, social sanctions work more effectively in regulating the behaviors of economic actors when the norm of reciprocity is widely observed, exchange relationships are long term in nature, and economic transactions are conducted in a communal setting. These three pre-conditions for social sanctions to work are more likely to be found in those societies marked by dense social fabrics. In such cases, social sanctions will be used more widely as a substitute for legal sanctions to remedy the weakness of market sanctions, wherein business entertainment will also be used more widely to enhance the power of social sanctions in regulating the behaviors of economic actors.

The density of social fabrics varies systematically across societies along the spectrum of collective versus individualistic cultures (Triandis, Reference Triandis1994). Japan, for instance, represents a collectivist society where most people identify themselves by their social status relative to others in the community. This collectivist culture is rooted in Japanese Confucianism, which originated in China but was expanded to include Buddhism and Shinto ethics in Japan (Ooms, Reference Ooms1985). Confucian teachings on the norm of goodwill reciprocity have been deeply indoctrinated in the mind of Japanese people, who tend to align their personal conduct with the long-term well being of the community (Bellah, Reference Bellah1985). As a whole, Japanese society can be seen as a tightly woven network, where the self-image of an individual is tied to the reputation of the social group. The density of social fabrics in the Japanese society, thus, is critical to the establishment and enforcement of collective behavioral norms.

On the contrary, the US is an individualistic society that lacks dense social fabrics to support the imposition of behavioral norms on economic actors. Thanks to their individualistic culture based on the Protestant heritage, Americans honor independence, self-reliance, and self-success more than collective achievements (Berry, Reference Berry1979). Built on individuals instead of groups, the American society is characterized by a high degree of mobility and personal freedom, making it difficult to establish and enforce collective social norms (Inglehart & Baker, Reference Inglehart and Baker2000). Moreover, immigrants with distinct cultural backgrounds hold different value systems that are confined within ethnic barriers (Triandis, Reference Triandis1989). Owing to the fragmented nature of an individualistic society, Americans are more respectful of privacy and more tolerant of deviant behaviors, and less willing to monitor each other or enforce social norms.

The lack of dense social fabrics in the US allows the society to develop a market economy that is largely separate from social life (Block, Reference Block2003). Further, such social and cultural heritages make impartial enforcement of legal regulations easier. In cases where market sanctions are weak, exchange relationships in the US will be regulated through legal sanctions rather than social sanctions (Greif, Reference Greif2004). Because collective norms play a minor role in transaction governance, business entertainment is less widely used in the US to boost the power of social sanctions to remedy the failure of market sanctions.

Coincidently, the prominence of legal sanctions as a remedy for weak market sanctions in the US also increases the efficacy of regulatory bans on business entertainment. In fact, the US government has imposed strict regulations to reduce certain entertainment activities in private business settings (Dresser, Reference Dresser2006). In those sectors where market power is strong (e.g., the financial sector), the US government has zero tolerance for relation-based business practices involving cronyism, nepotism, and insider trading. Such regulations even go beyond the national borders to restrict US firms that operate in those foreign countries where business entertainment is pervasive and legitimate (McCubbins, Reference McCubbins2001).

Hence, the variations in the density of social fabrics across nations can also predict the prevalence of business entertainment across societies. When social fabrics are dense in a society, social sanctions will play a greater governance role (relative to legal sanctions) to correct for the weakness of market sanctions. Because business entertainment serves to reinforce the governance power of social sanctions, it will be more widely seen in those societies featuring dense social fabrics. Thus,

Proposition 3: Business entertainment will be used more prevalently in those societies featuring dense social fabrics, ceteris paribus.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we take a governance approach to theorize the positive role of business entertainment in facilitating economic exchanges. We start our conceptualization by defining the governance devices of market, legal, and social sanctions. In particular, we explain how social sanctions work to regulate the behaviors of economic actors and further argue that business entertainment plays a role to strengthen the three conditions under which social sanctions work more effectively in governing exchange relationships, namely, supporting the norm of reciprocity, building long-term relationships, and weaving communal networks. Given this governance role, business entertainment should be more prevalent in those societies that rely more on social sanctions but less on legal sanctions to correct for the weakness of market sanctions. To further certify our governance view, we put forth a set of propositions that can predict the pervasiveness of business entertainment in a society based on the mixture of market, legal, and social sanctions adopted by the society to govern economic exchanges.

Our governance view on business entertainment answers the three questions raised earlier in the paper. First, our analysis provides a systematic account for the positive role of business entertainment in facilitating economic exchanges, where entertainment events serve to enhance the governance power of social sanctions in regulating the behaviors of economic actors. Second, this governance view highlights the win-win outcome for both parties in an entertainment event, i.e., the savings on transaction costs when social norms are more effective than legal restraints in remedying the weakness of market rules. Third, the governance model justifies the variations in the prevalence of business entertainment across societies, i.e., entertainment events are more likely to be seen in those societies with dense social fabrics but insufficient market and legal infrastructures.

This study contributes to the literatures on management, economics, and sociology by establishing a governance role for business entertainment to play in economic exchanges. Both policymakers and practitioners can draw useful implications from our conceptualization. The analysis also points out several promising directions for future research to advance our understanding of this prevalent but often misunderstood business practice.

Research Contributions

The primary contribution of this study is the adoption of an interdisciplinary approach to develop an economic theory for the social practice of business entertainment. Sociologists have long recognized the role of such entertainment events as group eating and social drinking in nourishing social relationships (e.g., Mintz & Bois, Reference Mintz and Bois2002). Previous sociology studies, nevertheless, have not recognized the governance function of business entertainment. Although economists have accepted social sanctions as a governance device of market transactions (e.g., Macaulay, Reference Macaulay1963), their conceptualization does not consider the role of business entertainment as a booster of social sanctions in the governance of economic exchanges. In this study, we fill the literature gap by establishing a governance role for business entertainment to play in economic exchanges. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that takes a governance view to propose a systematic account for business entertainment.

Our second contribution is the extension of guanxi studies to business networks and connections that are built and maintained mostly through entertainment events (see Yang, Reference Yang1994). As argued in guanxi studies, informal business connections can supplement formal institutions (Xin & Pearce, Reference Xin and Pearce1996) and save on transaction costs (Lovett et al., Reference Lovett, Simmons and Kali1999). According to our analysis, guanxi built through voluntary and non-corruptive entertainment events plays a constructive role to reinforce the governance power of social sanctions in facilitating economic exchanges that market and legal sanctions have both failed to support. Unlike most guanxi studies that see business entertainment as a culture-specific practice rooted in Chinese traditions (Manion, Reference Manion1996), our governance view offers a systematic account for business entertainment in all societies. This general view suggests that business entertainment can raise societal welfare by creating a win-win outcome for the parties to an exchange relationship.

Lastly, the relativity model of transaction governance on which our governance view of business entertainment is built contributes to organizational economics. We make this contribution by expanding the current governance theories that were developed in the West to include alternative economic systems that exist mostly in the East. For instance, the market-contract-hierarchy paradigm in transaction cost economics has been criticized for its lack of generalizability to certain Asian societies (e.g., Hamilton & Biggart, Reference Hamilton and Biggart1988). It has been found in Japan that the presence of specific assets does not necessarily raise transaction costs or result in vertical integration (e.g., Dyer, Reference Dyer1997). According to our relativity model of transaction governance, the relative availability and effectiveness of market, legal, and social sanctions in each society shape its optimal TGS. Because social norms are widely used to address market failure in Japan, the presence of specific assets does not always increase contracting costs, which then reduces the need for Japanese firms to bypass an inefficient market through vertical integration. Obviously, a social dimension can also be found in organizational economics.

Practical Implications

Practitioners can derive clear and useful guidelines from our governance view on business entertainment. Based on our study, policymakers have the need to reconsider the extension of domestic laws to regulate homegrown multinationals in foreign countries. An outright ban of business entertainment might hurt the competitiveness of homegrown multinational in those foreign countries featuring a TGS that uses social sanctions heavily to govern economic exchanges. For instance, the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977 has been a hindrance to the success of US firms in less developed nations inflicted with insufficient market and legal infrastructures (Hines Jr., Reference Hines1995). This study suggests that home governments, especially those with a prevailing rational legal system, should be more discriminating in projecting their regulations on business practices to emerging markets.

Likewise, policymakers in such countries as China can find a solution from this study to root out corruptive business practices. Although business entertainment does play a governance role in facilitating economic exchanges, it has a corrupt side that needs to be regulated. To minimize the abuse of business entertainment to corrupt an exchange relationship, the governments in less developed countries can invest more to develop market and legal infrastructures. Predictably, business entertainment will be less widely adopted to facilitate economic exchanges in such societies as China if market rules and legal restraints are strong enough to regulate the behaviors of economic actors.

Managers who run global operations must strike a balance when deploying business entertainment as a governance tool. On the one hand, they must recognize the positive role of business entertainment as a booster of social norms that supplement legal restraints in correcting for the deficiency of market rules in governing economic exchanges. Entertainment activities deemed less proper at home could become a powerful tool to facilitate exchange relationships overseas. On the other hand, they should be sensitive to extravagant entertainment activities that are susceptible to misuse or even abuse by expatriate managers. Multinational enterprises can refer to our conceptualization in setting their worldwide policy on business entertainment that is flexible enough to accommodate TGS relativity across all host countries.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

As the first attempt to propose a systematic account for business entertainment, this study has three major limitations, which also point out several directions for future scholars to advance our governance view on business entertainment. First, our analysis covers only entertainment events in private business settings despite that entertainment events also occur between private citizens and public servants. Entertainment events in this private-public setting might be more corruptive in nature. Future researchers can follow our governance approach to probe the characteristics of such entertainment events that are prevalent in certain parts of the world.

Second, our conceptualization does not distinguish between various formats of entertainment activities, such as eating, drinking, gift giving, sporting, traveling, and so on. Nonetheless, our analysis constructs a basis for future studies to verify empirically whether all types of entertainment events play the same governance role in regulating the behaviors of economic actors and, if not, whether one type of entertainment event is more powerful than another in supporting economic exchanges. Such empirical tests can compare different types of entertainment activities across societies, industries, companies, or even across exchange relationships.

Last but not least, this study limits social sanctions to secular sanctions without including spiritual sanctions. We do this deliberately to retain the generalizability of our analysis to all societies, secular or religious. Future research can extend our relativity model of transaction governance to include the role of religion in regulating the behaviors of economic actors. This extension is particularly important in those societies whose members also abide by the spiritual guidelines imposed by non-human agencies, such as God, deceased ancestors, occult forces, and so on (Piddocke, Reference Piddocke1968).

CONCLUSION

In this study, we combine sociology research on social sanctions and economics research on transaction governance to propose a systematic account for business entertainment. More specifically, we argue that business entertainment can strengthen the three conditions under which social sanctions work to govern economic exchanges. This governance role of business entertainment, hence, is more prominent in those societies featuring dense social fabrics but insufficient market and legal infrastructures. The governance view on business entertainment contributes to the literatures on management, economics, and sociology. Our analyses offer useful guidelines for policymakers and executives to regulate and manage a popular business practice that might otherwise be misused or even abused. As the first attempt to theorize business entertainment, this study also points out several promising directions for future researchers to advance our understanding of business entertainment under the governance framework.