The literatures on perceptions of immigrants across fields such as communication, psychology, and political science highlight perceived threats of immigration (economic, cultural, and otherwise) as key determining factors of attitudes toward immigrants (e.g., Seate & Mastro, Reference Seate and Mastro2016; Stephan & Stephan, Reference Stephan, Stephan and Oskamp2000; Valentino et al., Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2012; Watson & Riffe, Reference Watson and Riffe2013). Threat is also generally found to be a political motivator (Miller & Krosnick, Reference Miller and Krosnick2004). Perceptions of threat are related not only to negative attitudes and interpersonal discrimination, but also to support for large-scale anti-immigrant policies, such as the border wall and the Muslim ban (e.g., Green, Reference Green2009; Watson & Riffe, Reference Watson and Riffe2013; for a review, see Hainmueller & Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014).

While perceived threat is demonstrated to be a key predictor of anti-immigrant attitudes, much less work has examined how individual differences in sensitivity to threat relate to immigration attitudes. A growing literature has investigated the relationship between dispositional sensitivity to threat and political attitudes more broadly (e.g., Arceneaux et al., Reference Arceneaux, Dunaway and Soroka2018; Hibbing et al., Reference Hibbing, Smith and Alford2014). For the most part, these studies focus on the relationship between dispositional threat sensitivity and political ideology in general. Therefore, relatively little work thoroughly investigates the relationship between threat sensitivity and domain-specific political attitudes, such as those related to immigration.

In the current study, we add to these literatures by experimentally investigating the relationship between physiological threat sensitivity and immigration attitudes, thus drawing together research on physiological threat sensitivity as it relates to political ideology and research that emphasizes the importance of perceived threat to anti-immigrant attitudes. Given that individuals higher in threat sensitivity respond more strongly to perceived threats, and that immigrants are perceived as threats, we expect that those high in threat sensitivity will have more negative attitudes toward immigrants. Our study confirms the expectation that higher physiological threat sensitivity is associated with stronger anti-immigrant attitudes.

Threat perception and intergroup attitudes

Perceived threat has long been connected to intergroup attitudes. Many psychological theories of intergroup relations include threat as a predictor of out-group prejudice. For example, realistic group conflict theory (Campbell, Reference Campbell and Levine1965; Sherif, Reference Sherif1966) proposes that prejudice toward out-groups is caused by perceived competition over limited resources leading to perceptions of group threat and, consequently, negative attitudes and discriminatory behavior toward the apparently threatening out-group (Craig & Richeson, Reference Craig and Richeson2014). This theory focuses on threat related to physical resource scarcity (“realistic” threat), but research also demonstrates the importance of perceived threats to group values and cultural norms (“symbolic” threat) (Sears, Reference Sears, Katz and Taylor1988). Several studies link perceived symbolic threat to anti-immigrant attitudes. In particular, perceptions of realistic and symbolic threats are shown to lead to increased prejudice and aggressive behaviors against immigrants (e.g., Zárate et al., Reference Zárate, Garcia, Garza and Hitlan2004). Realistic group conflict theory and symbolic threat theory were later combined into integrated threat theory, which also encompasses the roles of intergroup anxiety and negative stereotypes (Stephan & Stephan, Reference Stephan, Stephan and Oskamp2000). Of course, threat also features prominently in several other theories of intergroup relations, such as group esteem threat (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979), distinctiveness threat (Tajfel & Turner, Reference Tajfel, Turner, Worchel and Austin1986), and the biocultural model of threat (Neuberg & Cottrell, Reference Neuberg, Cottrell, Mackie and Smith2002).

Perceptions of threat are also related to support for large-scale anti-immigrant policies—threat perceived from increases in immigration specifically is shown to lead to greater support for policies that restrict immigration and disadvantage immigrants. Wilson (Reference Wilson2001) finds that the extent to which Americans perceive immigrants as a threat to their self-interests was associated negatively with support for policies that are beneficial to immigrants. Alvarez and Butterfield (Reference Alvarez and Butterfield2000) find that those geographically closer to the source of immigration (and thus for whom growing immigration populations were most salient) were more likely to support an anti–illegal immigration proposition in California. Rink and colleagues (Reference Rink, Phalet and Swyngedouw2009) find a similar pattern in Belgium—greater numbers of immigrants entering the country were associated with increased support for the anti-immigrant political party.

This is not to say that threat has a universal effect—in some cases, the perceived threat of immigration appears to be dependent on individual differences. In fact, Hawley (Reference Hawley2011) finds that in the absence of a potentially threatening context, partisanship was a weak predictor of support for immigration restriction, but if their local surroundings included a large immigrant population, Republicans were far more likely than independents to support immigration restrictions, and Democrats were less likely. In sum, decades of research indicate that perceptions of threat are associated with animosity and hostility toward minority groups, and immigrants in particular.

Threat sensitivity

Much of the research on threat and immigration focuses specifically on the role of perceived threat in determining anti-immigrant attitudes and policy preferences (e.g., Brader et al., Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Green, Reference Green2009; Hainmueller & Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014; Harell et al., Reference Harell, Soroka, Iyengar and Valentino2012; Seate & Mastro, Reference Seate and Mastro2016; Sirin et al., Reference Sirin, Valentino and Villalobos2017; Valentino et al., Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2012; Valentino et al., Reference Valentino, Soroka, Iyengar, Aalberg, Duch, Fraile, Hahn, Hansen, Harell, Helbling, Jackman and Kobayashi2019). However, a growing psychophysiological literature suggests that individuals may vary in their sensitivity to threat—that is, their propensity to both attend closely and react intensely to threatening stimuli in their environments (Arceneaux et al., Reference Arceneaux, Dunaway and Soroka2018; Coe et al., Reference Coe, Canelo, Vue, Hibbing and Nicholson2017; Dodd et al., Reference Dodd, Balzer, Jacobs, Gruszczynski, Smith and Hibbing2012; Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, Soroka and Nir2020; Osmundsen et al., in press; Oxley et al., Reference Oxley, Smith, Alford, Hibbing, Miller, Scalora, Hatemi and Hibbing2008; cf. Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Schumacher, Gothreau and Arceneaux2020). Given the immigration literature’s emphasis on threat, research on threat sensitivity may provide a novel insight into the determinants of anti-immigrant attitudes.

Although early work found that individuals with high threat sensitivity tend to be more supportive of broadly conservative policies designed to minimize threat (e.g., Oxley et al., Reference Oxley, Smith, Alford, Hibbing, Miller, Scalora, Hatemi and Hibbing2008), more recent research has been unable to replicate these findings (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Schumacher, Gothreau and Arceneaux2020; Osmundsen et al., in press). Note, however, that our argument does not hinge on a relationship between threat sensitivity and social conservatism at large. Rather, we argue that people who are more sensitive to threatening stimuli will respond more strongly to the perceived threats of immigration.

Some of the research on threat sensitivity and political ideology explores the possibility that threat sensitivity might relate to specific policy attitudes, rather than general political ideology. For example, Bakker and colleagues (Reference Bakker, Schumacher, Gothreau and Arceneaux2020) analyze the relationship between threat sensitivity and attitudes in 16 policy domains, including immigration. Although their findings show no evidence of a relationship between threat sensitivity and immigration attitudes, their analysis relies on a single-item measure of each policy attitude. The measure they use, which asks about attitudes regarding deportation, may not be reflective of attitudes toward immigrants and immigration more broadly. Therefore, we argue that the relationship between threat sensitivity and immigration attitudes has yet to be thoroughly investigated.

Note also that although threat sensitivity has not been directly tied to immigration attitudes, recent work identifies an indirect connection: Cheon and colleagues (Reference Cheon, Livingston, Hong and Chiao2014) find that individual variation in the presence of a specific gene can influence sensitivity to perceived threats from out-groups. Moreover, the presence of this gene interacts with exposure to out-group members, resulting in greater levels of intergroup bias. These results speak to perceived out-group threat and intergroup bias in general but provide some indication that threat sensitivity may relate to immigration attitudes.

This possibility is further supported by work on disgust sensitivity. Aarøe et al. (Reference Aarøe, Petersen and Arceneaux2017) argue that the behavioral immune system, a mechanism designed to protect against pathogen-related threats, works outside of conscious awareness and has evolved to be “hypervigilant” against unfamiliar stimuli, including individuals with an unfamiliar appearance. In their cross-national study, they find that individual differences in behavioral immune sensitivity, operationalized as both physiological and self-reported disgust sensitivity, are associated with increased opposition to immigration. They further demonstrate the relationship between disease threat and immigration attitudes by showing that exposure to stimuli with disease protection cues (versus without) decreases the effect of behavioral immune sensitivity on immigrant attitudes.

Building on the importance of threat in the immigration literature, the psychophysiological literature on threat sensitivity, and recent work by Aarøe et al. (Reference Aarøe, Petersen and Arceneaux2017) that demonstrates the behavioral immune system’s influence on opposition to immigration, we hypothesize that threat sensitivity is positively related to anti-immigrant attitudes.

H1: Respondents higher in physiological threat sensitivity will more strongly endorse anti-immigrant attitudes than those lower in physiological threat sensitivity.

Methods

To test this hypothesis, we collected both self-report and psychophysiological data. Participants first viewed a series of threatening and positive photos while their skin conductance levels were being measured to ascertain physiological threat sensitivity. They were then asked about their attitudes toward immigrants.

Participants

Eighty participants were recruited through snowball sampling in a large Midwestern university town and paid US$10 for their participation in the study. This method of recruitment is commonplace for psychophysiological studies (i.e., Arceneaux et al., Reference Arceneaux, Dunaway and Soroka2018; Coe et al., Reference Coe, Canelo, Vue, Hibbing and Nicholson2017). Six of the participants were removed because of faulty measurement of physiological signals. Because of further concerns about the quality of the physiological data, 14 additional participants were removed (see Measures). Therefore, the sample used in this analysis contained 60 participants. Three participants did not indicate ideology and one did not indicate gender, so they were also removed in analyses involving these variables. The sample was 57% female (34 female, 25 male, 1 did not answer), 53% White (32 White, 13 Asian, 11 Hispanic, 3 Black or African American, and one “other”), with 72% of participants falling between 18 and 24 years of age. On a standard scale of ideology (ANES, 2016, described later), with 0 being liberal and 1 being conservative, the majority of participants identified as relatively liberal (M = 0.30, SD = 0.23) and, on a 0–1 scale of partisanship, as Democrats (M = 0.25, SD = 0.25).

Procedure

After providing informed consent, participants were seated in front of a computer, where biosensors were then connected to the first and third fingers of their nondominant hand. Wearing noise-canceling headphones, participants viewed a randomized photo array, beginning with a 60-second gray screen. Twenty-two photos from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS) and Chicago Face Database (CFD) were selected as stimuli (Codispoti et al., Reference Codispoti, Bradley and Lang2001; Ma et al., Reference Ma, Correll and Wittenbrink2015). Each stimulus was presented for 8 seconds with a 10-second interstimulus interval. Participants passively viewed the array of photos while their skin conductance was measured. These IAPS images were chosen as our stimuli because they are carefully pretested and coded along normative ratings of emotions and attention, creating a standardized and internationally accessible set of images (Lang et al., Reference Lang, Bradley and Cuthbert2008). In addition, this photo database has been used in prior psychophysiological studies (e.g., Soroka, Fournier, Nir, & Hibbing, Reference Soroka, Fournier, Nir and Hibbing2019).

For the focus of this article, only eight of the IAPS photos are analyzed: four emotionally threatening photos—a striking snake (IAPS 1050), a dog baring its teeth (IAPS 1300), a person with a gun in another person’s mouth (IAPS 3530), and a gun pointed at the viewer (IAPS 6260)—and four positive photos: flowers (IAPS 5202), a waterfall (IAPS 5260), a baby (IAPS 2058), and an ice cream sundae (IAPS 7330). Disgusting photos (e.g., vomit in a toilet), affectively neutral photos (e.g., a wicker basket), and photos of faces of different races (from the CFD) were also shown but are not relevant for this investigation.

Following the photo array, participants were asked to complete a short survey. They responded to batteries of questions about the environment and empathy, which were used as part of a larger data-collection effort. Participants were also randomly assigned to read one of two fabricated versions of an immigration news story or a control story about farming, all pertaining to the United States. This manipulation (along with the questions about empathy and the environment) was part of a broader project on immigration attitudes, but it is not relevant to the current study and, while it did precede the outcome measure used here, there were no differences among the three conditions on anti-immigrant attitudes.Footnote 1

Measures

Threat sensitivity

There is an ongoing debate in recent biopolitical research as to how threat sensitivity should be conceptualized (e.g., Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Schumacher, Gothreau and Arceneaux2020; Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, Soroka and Nir2020; Osmundsen et al., in press; Smith & Warren, Reference Smith and Warren2020). We conceptualize threat sensitivity as an individual’s predisposition to be sensitive (i.e., attend closely and react intensely) to any (but not necessarily all) threatening stimuli in their environment (see Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, Soroka and Nir2020).

In the biopolitical literature, threat sensitivity is typically measured using psychophysiological sensitivity to threatening images. This body of work is based on the premise that the presence of a threatening stimulus in an organism’s environment prompts activation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), which is associated with the “fight or flight” response. Thus, individuals with high threat sensitivity experience consistently higher levels of SNS activation in response to threatening stimuli than do individuals with low threat sensitivity (Oxley et al., Reference Oxley, Smith, Alford, Hibbing, Miller, Scalora, Hatemi and Hibbing2008). Compared with other physiological responses, skin conductance is both easy to measure, requiring only two small sensors attached to a participant’s fingers, and straightforward to interpret because of its direct association with SNS activation (Shields et al., Reference Shields, MacDowell, Fairchild and Campbell1987). The ease of use and ostensible theoretical clarity have led to the wide use of skin conductance in the biopolitical literature (e.g., Coe et al., Reference Coe, Canelo, Vue, Hibbing and Nicholson2017; Dodd et al., Reference Dodd, Balzer, Jacobs, Gruszczynski, Smith and Hibbing2012; Hibbing et al., Reference Hibbing, Smith and Alford2014).

In line with previous work, we capture threat sensitivity using differences in skin conductance in response to threatening versus positive photos (Hibbing et al., Reference Hibbing, Smith and Alford2014).Footnote 2 Specifically, we measured skin conductance levels in response to a photo array of various photos taken from the IAPS. The raw signals were collected 256 times per second during the photo array. They were then smoothed and averaged using the same processes that were used for similar data in Soroka, Fournier, and Nir (Reference Soroka, Fournier and Nir2019).

Physiological data are challenging to collect, and sometimes sensors do not have a clear enough connection to reliably receive a signal from the participant (Potter & Bolls, Reference Potter and Bolls2012; Settle et al., Reference Settle, Hibbing, Anspach, Carlson, Coe, Hernandez, Peterson, Stuart and Arceneaux2020). Therefore, it was necessary to code the skin conductance signals for quality, which we did following the method employed by Soroka, Fournier, Nir, and Hibbing (Reference Soroka, Fournier, Nir and Hibbing2019). Independent of each other and before the analysis was conducted, four of the experimenters coded each participant’s skin conductance signal to ensure reliability. Signals were rated on a three-point scale of unusable, questionable, and normal. A rating of unusable indicated a flat signal for most or the entirety of the photo viewing task, suggesting an equipment malfunction. At least two coders agreed that six participants’ signals were unusable, so we discarded these data. A rating of questionable, assigned to 14 participants’ data by at least two coders, indicated that the signal was not obviously due to malfunction, as in the unusable category, but it was noisy and inconsistent with typical skin conductance patterns, suggesting the possibility of subtler equipment errors. The analyses presented here were conducted without the questionable data from the 14 participants. Our findings are partially but not completely robust to the inclusion of these participants’ data.Footnote 3

The averages of the stimulus-period photos were mean-centered relative to their pre-stimulus baseline counterparts, calculating an average difference in skin conductance (SC), in microsiemens, for each photo. Threat sensitivity was calculated by subtracting the average SC response to the positive photos from the average SC response to the threatening photos. The resulting threat sensitivity variable ranged from roughly –1 to 1, with higher values indicating higher threat sensitivity (M = 0.05, SD = 0.18).

There has been a great deal of discussion about the use of physiological measures, particularly skin conductance, to measure threat sensitivity. Some scholars have expressed doubts that this method is able to capture individual differences in threat sensitivity (e.g., Osmundsen et al., in press), although others remain supportive of the approach. We regard the tests that follow as being more prone to Type II errors than Type I errors. To the extent that this method is not capturing individual differences in threat sensitivity, we do not expect it to correlate with our outcome. In other words, if this physiological measure does indeed reflect noise rather than trait threat sensitivity, there is no reason to expect it to predict immigration attitudes.

Self-report threat sensitivity

We also measured self-reported threat sensitivity using a 12-item Belief in a Dangerous World Scale (BDW; Altemeyer, Reference Altemeyer1988) (e.g., There are many dangerous people in our society who will attack someone out of pure meanness, for no reason at all; any day now chaos and anarchy could erupt around us), with responses on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) Likert scale. This scale has been used as an indicator of dispositional threat sensitivity in previous research (Weber & Federico, Reference Weber and Federico2007; Wright & Baril, Reference Wright and Baril2013). Five of the items were reverse scored so that higher numbers indicated greater threat sensitivity, and the data were then rescaled to fit a 0–1 scale (M = 0.43, SD = 0.14, α = 0.77).

Anti-immigrant attitudes

To gauge anti-immigrant attitudes, we ask participants whether they believe that illegal immigration is an important national issue.Footnote 4 We also include an adapted version of Iyengar and colleagues’ (Reference Iyengar, Jackman, Messing, Valentino, Aalberg, Duch, Hahn, Soroka, Harrell and Kobayashi2013) four-item measure of anti-immigrant sentiment. The items ask participants to indicate their agreement, on a 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) scale, with a variety of immigration specific statements, for example, that “the U.S. is admitting too many immigrants.” These five items were then combined into an index and rescaled to range from 0 to 1, with higher numbers representing stronger anti-immigrant attitudes (M = 0.34, SD = 0.16, α = 0.69). While this inter-item reliability is not ideal, dropping any item from the index failed to improve the index and, in some cases, decreased its reliability, so we decided to retain these items as an index.

Control variables

Because anti-immigrant attitudes are divided along party lines (Pew Research Center, 2019), we included measures of partisanship and political ideology to control for these effects. In order to reduce multicollinearity, the analyses presented here either include political ideology or party identification. Partisanship was measured using the three-part party identification questions from the American National Election Studies (ANES, 2016), which ask participants (1) whether they identify as Republican, Democrat, or independent; then (2) how strongly they identify with their party; and finally, if they selected independent, (3) whether they are closer to the Republican or Democratic Party. The three questions were combined, resulting in a final response scale of strong Democrat, not very strong Democrat, independent leaning Democrat, independent, independent leaning Republican, not very strong Republican, and strong Republican. These were recoded from 0 to 1, where 0 is strong Democrat and 1 is strong Republican.

Political ideology was measured with one survey item asking participants to indicate the extent to which they lean liberal or conservative. The measure comes from the current ANES (2016) standard questions. The 7-point liberal-conservative self-identification question asks, “When it comes to politics do you usually think of yourself as extremely liberal, liberal, slightly liberal, moderate or middle of the road, slightly conservative, conservative, extremely conservative, or haven’t you thought much about this?” Responses of not having thought much about it were deleted, and the rest were rescaled that so that 0 is extremely liberal and 1 is extremely conservative.

In keeping with past research on anti-immigrant attitudes (e.g., Knoll et al., Reference Knoll, Redlawsk and Sanborn2011; Merolla et al., Reference Merolla, Ramakrishnan and Haynes2013), we also measured education, gender, age, race, church attendance, and union membership, which have been shown to be related to anti-immigrant attitudes (e.g., Citrin et al., Reference Citrin, Green, Muste and Wong1997; Hughes & Tuch, Reference Hughes and Tuch2003; Knoll, Reference Knoll2009; Oliver & Wong, Reference Oliver and Wong2003; Tolbert & Grummel, Reference Tolbert and Grummel2003; Wilson, Reference Wilson1996).

Results

In order to test the presence and stability of the relationship between threat sensitivity and anti-immigrant attitudes, we estimated a series of ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models, first with just threat sensitivity as the independent variable, then with the addition of the key demographic variables of education, age, gender, and party identification, and finally substituting political ideology for party identification. P-values in Tables 1 and 2 are based on two-tailed tests. Note that we also tested models with controls for union membership and religious attendance, but these variables did not influence the significance of the variables of theoretical interest, so they are omitted throughout.

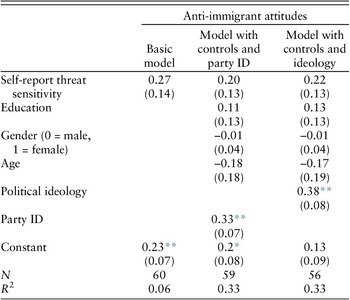

Table 1. Physiological threat sensitivity predicting anti-immigrant attitudes.

* p < .05;

** p < .01.

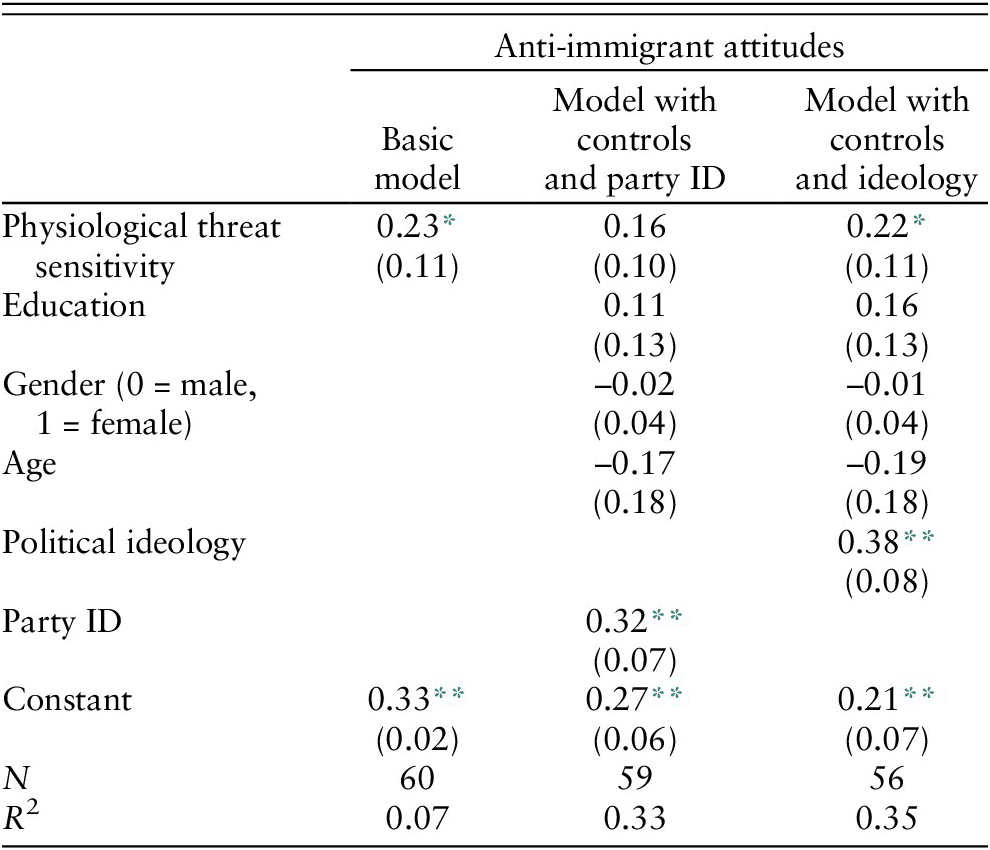

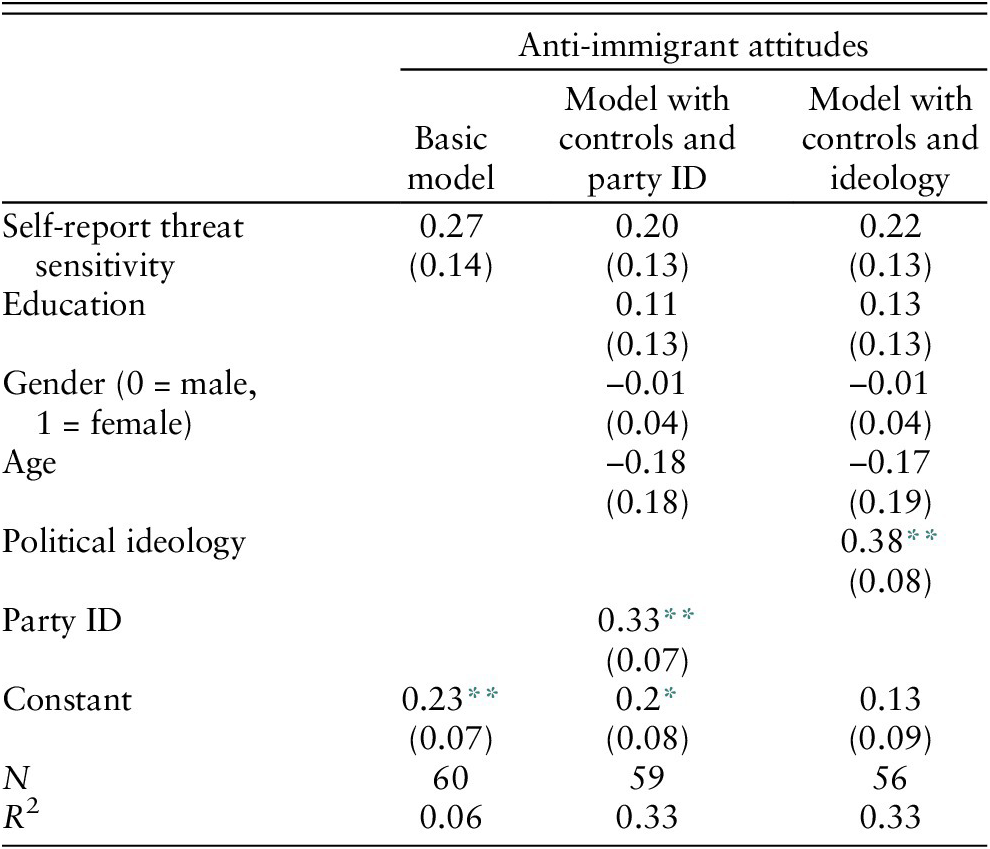

Table 2. Self-reported threat sensitivity predicting anti-immigrant attitudes.

* p < .05;

** p < .01.

As depicted in Table 1, in the first model, physiological threat sensitivity is significantly and positively related to anti-immigrant attitudes (β = 0.23, SE = 0.11, η2 = 0.07). When controlling for age, gender, education, and party identification in the model, party identification is significant (β = 0.32, SE = 0.07, η2 = 0.25), but threat sensitivity is not (β = 0.16, SE = 0.10, η2 = 0.03). However, when substituting political ideology for party identification, both ideology (β = 0.38, SE = 0.08, η2 = 0.27) and threat sensitivity (β = 0.22, SE = 0.11, η2 = 0.05) significantly predict anti-immigrant attitudes. We infer from these findings that part of the effect of physiological threat sensitivity may be captured by partisanship, but not by ideology. There are ongoing debates about the ways in which threat sensitivity and ideology may or may not be related (see Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, Soroka and Nir2020). Our aim is not to assess these relationships in detail, however. Our primary inference from Table 1 is that physiological threat sensitivity is indeed related to anti-immigrant attitudes, albeit conditional on whether partisanship is included in the model. We consider this pattern of findings in more detail in the discussion section.

How does our self-reported measure of threat sensitivity relate to immigration attitudes? We report results of the same models estimated using self-reported threat sensitivity in Table 2. The self-reported measure is not significantly associated with anti-immigrant attitudes, regardless of the inclusion of control variables. These results do not change when physiological threat sensitivity is included as an independent variable alongside self-reported threat sensitivity. It is also of some significance that our measure of physiological threat sensitivity is not significantly correlated with self-reported threat sensitivity (r = 0.05, p = .72). We consider this finding in more detail below.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that individual differences in reactions to one’s environment may have important implications for intergroup attitudes. Research on immigration has demonstrated that perceptions of threat are a driving factor in intergroup relations, especially for attitudes toward immigrants (e.g., Esses et al., Reference Esses, Haddock, Zanna, Mackie and Hamilton1993; Stephan & Stephan, Reference Stephan, Stephan and Oskamp2000; Valentino et al., Reference Valentino, Brader and Jardina2012). Although threat responses are automatic and universal, research has shown that there may be individual differences in sensitivity to threat (e.g., Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, Soroka and Nir2020; Grosser et al., Reference Grosser, Wechsler and Greenblatt1964; Osmundsen et al., in press; Oxley et al., Reference Oxley, Smith, Alford, Hibbing, Miller, Scalora, Hatemi and Hibbing2008; cf. Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Schumacher, Gothreau and Arceneaux2020). Connecting work on threat and immigration to work on threat sensitivity, we find that anti-immigrant attitudes are linked to threat sensitivity. Specifically, we find that physiological threat sensitivity predicts anti-immigrant attitudes in the expected direction—that is, people with high threat sensitivity tend to have stronger anti-immigrant attitudes than people with low threat sensitivity.

To be clear, our results demonstrate a correlation between threat sensitivity and anti-immigrant attitudes, not a causal relationship. However, in combination with previous research on immigration attitudes and threat sensitivity, our study provides a basis for speculation and future research on the nature of this relationship. Our focus here is on the possibility that threat sensitivity may influence anti-immigrant attitudes. We believe this is the most likely direction of causality because, in line with previous work, we regard threat sensitivity as at least partially a function of biological predispositions (Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, Soroka and Nir2020), causally prior to a range of political attitudes (e.g., Cheon et al., Reference Cheon, Livingston, Hong and Chiao2014). Consider that our measure of threat sensitivity reflects responsiveness to threatening stimuli unrelated to immigration, making it very unlikely that responses to the threatening photos were driven by attitudes about immigration. Threat sensitivity also was measured prior to any mention of immigration in the study. Thus, there is no reason to believe participants were thinking about immigration when they responded to the threatening photos. We cannot rule out the possibility of a spurious relationship, of course. But we see our findings as adding to a growing body of work connecting threat sensitivity to political attitudes.

Theoretically, the effect we suggest may occur through one or both of two processes: differential attention and differential response. First, people who are highly sensitive to threats are more likely to attend to threatening stimuli in their environment. Second, highly threat-sensitive people are predisposed to react more strongly to those threats. Because immigrants are typically viewed as threats (e.g., Riek et al., Reference Riek, Mania and Gaertner2006), people high in threat sensitivity may attend more closely or react more strongly to the perceived threats of immigration, with either path resulting in stronger anti-immigrant attitudes.

Interestingly, our self-report measure of threat sensitivity was not associated with anti-immigrant attitudes or our physiological measure. The mismatch could be because of the well-established concern with self-report measures (Lucas, Reference Lucas, Diener, Oishi and Tay2018; Rosenman et al., Reference Rosenman, Tennekoon and Hill2011), because our chosen self-report measure for threat sensitivity (the BDW scale; Altemeyer, Reference Altemeyer1988) does not actually measure threat sensitivity, because of measurement issues with physiological threat sensitivity (Osmundsen et al., in press), or because self-report threat sensitivity and physiological threat sensitivity represent different constructs entirely. Note that Bakker et al. (Reference Bakker, Schumacher, Gothreau and Arceneaux2020) recently found that self-reported threat sensitivity relates more closely to ideology than does physiological threat sensitivity; in light of their findings regarding ideology and our findings regarding anti-immigrant attitudes, it may be that self-report and physiological threat sensitivity are each suitable measures for studying different domains. This points to a need to further specify the concept of “threat sensitivity.”

One relevant consideration is that the responses captured by these methods differ in the extent to which they rely on automatic versus reflective processes (e.g., Jarymowicz & Imbir, Reference Jarymowicz and Imbir2015). Physiological responses likely correspond more closely with emotional arousal than do responses to the BDW scale (e.g., Lang et al., Reference Lang, Kozak, Miller, Levin and McLean1980). Research has shown that emotional responses are consistently connected to perceptions of threat as it relates to out-groups (Stephan & Stephan, Reference Stephan, Stephan and Kim2017). This may explain why we find that anti-immigrant attitudes are associated with physiological but not self-reported threat sensitivity. Other work shows that the BDW scale does predict intergroup prejudice toward out-groups stereotypically associated with threats to safety, but not toward groups that present other types of threat (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Li, Newell, Cottrell and Neel2018). Thus, it may be that physiological threat sensitivity, which is relatively automatic and emotional, reflects sensitivity to different kinds of threat than does self-report threat sensitivity. Future work should examine the extent to which automatic and reflective processes are differentially implicated in perceptions of threat and subsequent policy preferences. In addition, because our findings suggest that physiological threat sensitivity may be related to different attitudinal domains than self-report threat sensitivity (see Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Schumacher, Gothreau and Arceneaux2020, Osmundsen et al., in press), we suggest that future work should continue to broaden its focus beyond political ideology and more systematically examine domain-specific differences in threat.

In retrospect, despite its use as a dispositional measure of threat sensitivity in past work, the BDW scale was not the appropriate measure to capture the self-report equivalency to physiological threat sensitivity in our study. Conceptually, the BDW scale reflects a cognitive evaluation of the state of the world, which should be largely distinct from automatic affective responses to a specific environmental stimulus. The null relationship we found between the physiological and self-report measures of threat sensitivity is consistent with this conceptual distinction. During the time that we were running this study, Kramer et al. (Reference Kramer, Patrick, Hettema, Moore, Sawyers and Yancey2019) were developing a self-report scale of fear/fearlessness that is meant to predict variations in physiological threat reactivity as indexed by startle potentiation. If we were to replicate this study, we would opt to include a measure like this fear/fearlessness scale, which would provide a more direct comparison between physiological and self-report measures of threat sensitivity. It is our belief that future research investigating the differences and similarities across various measures of threat sensitivity will bring us closer to understanding threat as a biological and/or attitudinal construct.

The relationship we find between physiological threat sensitivity and anti-immigrant attitudes supports the conclusion from prior work that automatic physiological responses can provide insights into the origins of intergroup attitudes (Aarøe et al., Reference Aarøe, Petersen and Arceneaux2017; Cheon et al., Reference Cheon, Livingston, Hong and Chiao2014). Note, however, that we only aim to demonstrate the relevance of threat sensitivity to anti-immigrant attitudes and not to draw a conclusion about the relationship between threat sensitivity and social conservatism that others have suggested (e.g., Arceneaux et al., Reference Arceneaux, Dunaway and Soroka2018; Hibbing et al., Reference Hibbing, Smith and Alford2014; Kanai et al., Reference Kanai, Feilden, Firth and Rees2011; Oxley et al., Reference Oxley, Smith, Alford, Hibbing, Miller, Scalora, Hatemi and Hibbing2008) and that recent work has failed to replicate (e.g., Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Schumacher, Gothreau and Arceneaux2020; Fournier et al., Reference Fournier, Soroka and Nir2020; Osmundsen et al., in press).

Importantly, it appears that physiological sensitivity to threat predicts attitudes toward immigrants independent of political ideology. Given that political ideology is generally a strong predictor of immigrant attitudes (e.g., Albertson & Gadarian, Reference Albertson, Gadarian, Freeman, Hansen and Leal2012; Hajnal & Rivera, Reference Hajnal and Rivera2012; Neiman et al., Reference Neiman, Johnson and Bowler2006), our results suggest that, as a predictor of anti-immigrant attitudes, threat sensitivity captures something distinct from political ideology. This account is further supported by our finding that ideology and physiological threat sensitivity were essentially uncorrelated (r = 0.08), consistent with recent work by Bakker et al. (Reference Bakker, Schumacher, Gothreau and Arceneaux2020).

The same is not true for party identification; when it is included in the model, it dominates physiological threat sensitivity, even though party identification was only weakly (and insignificantly) correlated with physiological threat sensitivity (r = 0.17). Why, then, does party identification dominate threat sensitivity? We suggest that this is attributable to one of two possibilities. The first possibility is measurement error: the participation of international students in our study compromises the party identification measure. The second possibility is that party identification’s dominance of threat sensitivity in our model does not negate the relationship between threat sensitivity and anti-immigration attitudes. Instead, it may be that one of the ways that threat sensitivity relates to anti-immigration attitudes is through party identification. In other words, although the relationship between threat sensitivity and partisanship is generally weak and noisy (Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Schumacher, Gothreau and Arceneaux2020), the effect of threat sensitivity on anti-immigrant attitudes may be partially mediated by partisanship. However, this is only speculation; with these data, we cannot determine why party identification dominates threat sensitivity. Moreover, a full exploration of the relationships between threat sensitivity, ideology, and partisanship is beyond the scope of this study. We suggest that our findings shed some light on this topic, but we emphasize the calls in prior work for more systematic research exploring these relationships.

Limitations and future directions

Although we regard our findings as a major step toward demonstrating the relationship between physiological threat sensitivity and anti-immigrant attitudes, this study has several important limitations. First, our sample size is relatively small (N = 60 in the conservative sample) and not racially diverse (over 50% White participants). Our study is not atypical in this regard; many physiological studies use small sample sizes because of the expensive and time-intensive nature of data collection (Aarøe et al., Reference Aarøe, Petersen and Arceneaux2017; Oxley et al., Reference Oxley, Smith, Alford, Hibbing, Miller, Scalora, Hatemi and Hibbing2008). A post hoc power analysis was conducted using the G*Power software package (Faul et al., Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Lang and Buchner2007) to determine the power of our sample size (N = 60) to detect a small (f 2 = .02), medium (f 2 =.15), and large (f 2 =.35) effect size (Cohen, Reference Cohen1977). We used a five-predictor variable equation and an alpha level of p < .05. The analysis indicated a statistical power of .98 for a large effect size, .75 for a medium effect size, and .14 for a small effect size. Since we were only sufficiently powered to detect a large effect size, our small sample size points to the need for replication in order to be more confident about our results, especially in light of the recent failures to replicate physiological results (e.g., Bakker et al., Reference Bakker, Schumacher, Gothreau and Arceneaux2020).

Second, in terms of participant recruitment, there are limitations to snowball sampling. Although this type of sampling method is typical for physiological research, snowball sampling means that representativeness of the sample (e.g., age, gender, and race) is not guaranteed. This is especially so because snowball sampling relies on participants recommending the study to their friends and acquaintances. As a result, the sample may be somewhat more homophilous than the baseline expected from a convenience sample.

Third, the racial composition of our sample is not reflective of the U.S. population. Of course, many studies about the perceived threats of immigration focus exclusively on White participants as they are the racial group with the most power in the United States to make changes about immigration policy (Brader et al., Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008; Craig & Richeson, Reference Craig and Richeson2014; Figueroa-Caballero & Mastro, Reference Figueroa-Caballero and Mastro2019). Unfortunately, because the racial composition of our sample was unevenly distributed, we had so little data for some races that analyses controlling for race would be meaningless. Further, while we could split the sample between participants who are White and people of color, we did not want to conflate views on immigration between racial groups with divergent immigration histories and cultures. Therefore, we leave the exploration of the role of racial identity to future studies with larger sample sizes that can account for these differences.

Additionally, a few participants told the experimenters that they were international students and thus did not relate as much as U.S. citizens would to the threat of immigration. Unfortunately, we did not include a question concerning citizenship or country of residence, so this effect is unknown. While it would have been ideal to have measured citizenship, we expect that our inability to control for it increases the variance in the outcome, making it more rather than less difficult to reject the null hypothesis. The fact that we find a significant relationship despite being unable to control for this additional source of variation provides stronger evidence for the relationship between physiological threat sensitivity and immigration attitudes.

Finally, though our threatening stimuli are drawn from the same set of images as past research on threat sensitivity, there is reason to be cautious about the categorization and interpretation of these images. We use only threatening images, so we cannot know that our results are driven by threat sensitivity rather than negativity bias more broadly. On one hand, past work suggests that the primary discrete emotional response to our chosen images is indeed fear (Barke et al., Reference Barke, Stahl and Kröner-Herwig2012). On the other hand, the IAPS was developed using an explicitly dimensional view of emotion that coded photos for arousal, valence, and dominance/control (see, e.g., Lang et al., Reference Lang, Kozak, Miller, Levin and McLean1980; Lang et al., Reference Lang, Bradley and Cuthbert2008); because that approach does not distinguish between negative images and threatening images, it is unclear from the original testing whether threat is sufficiently distinguished from negativity more generally. (Indeed, a considerable amount of research on threat sensitivity uses the two terms interchangeably; see, e.g., Osmundsen et al., in press; Oxley et al., Reference Oxley, Smith, Alford, Hibbing, Miller, Scalora, Hatemi and Hibbing2008). Furthermore, note that researchers’ intuitive categorizations of images are often inconsistent with participants’ emotional responses and that emotional responses to the IAPS can vary by country (Barke et al., Reference Barke, Stahl and Kröner-Herwig2012). The resulting inconsistencies may partially explain the mix of findings in the threat sensitivity literature. Thus, it would be advantageous for future work to theorize threat more explicitly and develop a set of stimuli that clearly distinguishes threat from negativity.

The limitations regarding sample size, method of recruitment, participant racial composition, participant international status, and choice of stimuli are important to highlight. Nevertheless, our study makes an important contribution to the study of public opinion about immigration by building on our understanding of the sources of anti-immigrant attitudes. Bringing together research that links perceived threat with negative attitudes about immigration, and research on physiological threat sensitivity as it relates to political ideology, we demonstrate that increased physiological threat sensitivity is linked to anti-immigrant attitudes. This suggests that immigration attitudes are impacted not only by momentary perceived threat, but also by enduring individual differences in reactivity to threat.

Note also that immigration issues are regularly connected to threat in media coverage, potentially exacerbating the connection between perceived threat and anti-immigration attitudes, especially among individuals who are highly sensitive to threat. Prior research suggests that immigrants are portrayed in the news media as threats to Americans’ resources, culture, and safety (Benson, Reference Benson2013), for instance. Narratives about immigrant threat are especially salient in recent years in the U.S., both in the news media and in national policy—consider recent legislation such as the Muslim ban, the border wall, and the zero-tolerance separation of families at the border. In light of the importance of threat in the context of public discussion of immigration, then, we believe physiological threat sensitivity provides a valuable window into the mechanisms behind public attitudes about immigration.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Stuart Soroka for his help in the design and implementation of the study. We also thank Erin Cikanek for her input on earlier versions of this project. Finally, we thank the Marsh Lab and the University of Michigan for the financial support that made this study possible.