CANADA'S HEALTHCARE SYSTEM

Since health technology assessment (HTA) in Canada was last reviewed by some of us in 1994 (Reference Battista, Jacob and Hodge3), the Canadian healthcare system has evolved and yet remained fundamentally constant. As we noted in the 1994 study, Canada was and remains a sparsely populated country. The population has grown to approximately 32 million people, and 80 percent of the population lives within 320 kilometers of the border with the United States. Despite occupying a landmass of roughly 10 million square kilometers, Canadians are clustered in large cities and their surrounding metropolitan areas.

Founding Principles

Canada's healthcare system is marked by an enduring combination of public financing and private provision. Public population-wide financing began in 1947 when the province of Saskatchewan established a public universal hospital insurance. At the national level, passage of the Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act in 1957 led the Government of Canada to negotiate with the provinces to share funding of acute hospital care and laboratory and radiological diagnostic services. By 1961, agreements were in place with all provinces and 99 percent of Canadians had free access to the health services covered by the legislation. However, physician services, notably outpatient services, remained largely uninsured.

In 1964, a Royal Commission on Health Services, chaired by Justice Emmett Hall, recommended a comprehensive and universal medicare system for all Canadians, including coverage of physician care and prescription drugs. By 1966, the majority of Canadians were insured for physician services through various private or public insurance plans.

Under Canada's federal structure, the thirteen provincial and territorial governments have jurisdiction over the provision of health services and thus, the Canadian “system” consists of thirteen slightly different “systems.” All are publicly funded through a combination of provincial government general revenue, specific income-associated health taxes, and transfer payments from the federal government to provincial and territorial governments (Reference Detsky and Naylor11;Reference Iglehart18). Population coverage for hospital and physician services is universal, contingent on provincial residency requirements of a few months duration, and private insurance companies are functionally banned from providing coverage for services provided through the universal coverage public funding envelope. By and large, coverage of drugs costs for outpatients and long-term care is not included in universal coverage, although all provinces have varying levels of coverage through means-tested programs for drugs and long-term care. This unique approach has generally fostered equitable access to services, but inequity may be growing as the number of uninsured or delisted services grows (Reference Schoen and Doty33).

Health System Institutions and Constituencies

Hospitals are not-for-profit organizations and not civil service institutions, but the single-payer system coupled with global budgeting for many hospital services, creates a functionally monopsonistic market for hospital services. Hospital-based healthcare workers, with the exception of physicians, are employed by these hospitals, although their working conditions are often determined through province-wide collective bargaining.

Physicians are compensated through a range of methods but, with few exceptions, are contractors. In primary care and outpatient settings, most physicians manage their own “small business medical practice,” typically unincorporated, and are paid through an increasingly complex combination of fee-for-service payments (i.e., volume-dependent) and some form of capitation or rostering payment (Reference Devlin and Sarma12). Hospital-based physicians function in much the same way, sometimes receiving reduced cost or free office space and/or other infrastructure access from hospitals in return for practicing at that facility. Very few physicians are employed by hospitals; thus, many hospitals are dependent upon relatively unstructured relationships with physicians to deliver the care demanded by the communities they serve.

In 1994, we noted that Canada's healthcare system seeks to achieve a balance among government direction, consumer choice, and provider autonomy (Reference Battista, Jacob and Hodge3). This quest for balance persists, reflecting the continued application of the Canada Health Act of 1984, which reaffirmed five principles that must be respected by provinces receiving federal cash transfers for health care: public administration, comprehensiveness, universality, portability, and accessibility.

Evolution Amid Constancy: Factors Shaping the System's Evolution

Given that the system's foundational aspects have changed relatively little, “evolution amid constancy” describes ongoing managed tensions in balancing government direction, consumer choice, and provider autonomy. These “evolutions” include how government exerts direction, consumer attitudes, and provider context.

Over the past two decades, all provincial governments have implemented some version of regionalization (Reference Lewis and Kouri27). These range from establishing relatively weak regional planning bodies to more powerful regional service delivery organizations that group and subsume individual hospitals and other facilities. Alberta introduced a bold move in 2008 with the formation of a single health board, to replace nine regional health authorities, with responsibility for health services delivery for the province as a whole. Proponents of regionalization cite the benefits of coordinated care, volume purchasing, reduced duplication of services, and reduced direct political control of allocation decisions while skeptics tend to point to promised yet unrealized “savings” and the continued politicization of decision making in regional health authorities as evidence that regional bodies have failed to deliver the results claimed for them (Reference Smith and Church34). In addition, some provinces have established variously named “quality councils” intended to report to the public on how the system is functioning. These changes can both be understood either as a dilution of the role of the government in directing the system or more cogently as an upstream move from the State as planner and service provider to the State as steward for the effective allocation of resources in health.

As everywhere, Canadian consumer attitudes toward health, health care, and health technologies are shaped by media. In Canada, proximity to the United States coupled with widespread availability of television originating in the United States creates an additional level of media influence. Despite the geographic proximity, however, such innovations as direct-to-consumer advertising for health technologies are far less widespread (and in some cases, prohibited) in Canada than in the United States. Distinct from the United States, the high importance that Canadians attach to health care is manifest in its consistent high profile in provincial and even federal politics. Perhaps the greatest change has been an increase in the proportion of Canadians expressing concern about the system's productivity (17) and sustainability through the 1990s (Reference Donelan, Blendon, Schoen, Davis and Binns13), and a concomitant intensification of consumer vigilance that they and their family members can receive services to which they believe they are entitled. At the bedside or clinic level, relatively high levels of dissatisfaction have been reported among Canadian nurses, not dissimilar to the ones reported in other English-speaking Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development health systems (Reference Aiken, Clarke and Sloane1).

At the societal level, several provincial governments have faced legal challenges regarding waiting times for care. Likely the most prominent has been the Chaoulli case in Quebec, decided by the Canadian Supreme Court in 2005. Dr. Chaoulli applied for a license from the Government of Quebec to provide services as an independent private hospital, effectively challenging a provincial legislative prohibition on private medical insurance. His request was denied, and he sought legal redress. The Supreme Court of Canada, in a complex 4–3 decision, ruled that the Quebec Health Insurance Act and the Hospital Insurance Act violated citizens' rights under the Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms and as such were rendered invalid (9). The Government of Quebec argued successfully for a stay of 12 months and subsequently introduced legislation permitting private insurance for selected surgical procedures. The longer-term implications of this decision remain to be seen.

For providers, the evolution of the system has important discipline-specific effects. Canada faces a nursing shortage that has been managed by means of a combination of substitution of other personnel for nursing work and skill-based immigration from developing countries (6). For physicians, the situation is complicated by the difficulty in establishing an optimal doctor-population ratio. Decisions made in the early 1990s to reduce medical school enrollment (Reference Barer and Stoddart2) have been reversed in the face of a perceived “doctor shortage,” which has also facilitated a loosening of restrictions on foreign-trained physicians being able to pursue licensure in Canada and a decline in the flow of Canadian physicians to the United States (7). Taken as a whole, the relationship between physicians and provincial governments appears to have evolved away from a narrow conditions-of-work negotiation, despite the absence of an employee-employer relationship with government, to one of shared accountability for the continued availability of physician services.

Mechanisms Modulating Technology Introduction and Use

The foundation of universal, public financing of privately provided services has shaped both the introduction of technologies and the evolution of HTA in Canada. This macro-level structural persistence of a single-payer publicly funded system buttressed by legislated impediments to private insurance has long functioned as a form of implicit HTA (Reference Evans and Banta14). Because provincial governments designate global funding envelopes for hospitals (or regional health authorities), new hospital construction can only occur with the blessing of government, including the designation of a global budget for any new facility. Furthermore, existing hospitals, while potentially able to raise capital funds through development efforts, must negotiate for the inclusion of operating costs associated with health technologies in their global budget. As a first approximation, public financing by means of global budgeting, coupled with filled-to-capacity hospitals, appears to have blunted competitive desires of hospitals to outdo each other with the latest technologies as has been seen in other health systems, notably the United States, because such a strategy is likely to be financially unsustainable.

Nevertheless, by the early 1990s, virtually all provinces were considering or introducing additional measures to manage technology adoption and use. This occurred at different rates in different provinces but emerged from a shared recognition of the bluntness of global budgeting as a “technology assessment/management” tool. In the larger provinces, the establishment of specific HTA bodies, typically at some distance from the policy process but intended to provide input to that process, was the most obvious of these responses.

For lower cost technologies, physician influence has been a more important determinant of diffusion (Reference Battista, Lance, Lehoux and Régnier4). This is particularly the case for those technologies (e.g., certain point of care devices) whose costs can be passed on to patients/consumers by means of direct billing. However, the relative undersupply of doctors, the majority of whom are in primary care settings, may have limited the entrepreneurial willingness of individual physicians to invest in free-standing, physician-owned alternatives to hospital-provided care for such technologies as endoscopy and diagnostic imaging. Moreover, in some provinces, the designation of separate professional fees (for the doing of a procedure and/or its interpretation) and technical fees (for the equipment and infrastructure costs) with the technical fee paid only in facilities to which the government has granted a permit, may explain the relatively low levels of physician-driven diffusion of technologies compared with other health systems with private provision of services.

EARLY HISTORY OF HTA

HTA in Canada emerged in a relatively favorable environment due to the convergence of several factors. These include a positive predisposition of clinicians, patients, and managers toward health science, and likely the paucity of Canada-based developers and producers of health technologies. Although the situation is somewhat less simple with pharmaceuticals, Canada's historically low levels of expenditure on research and development, coupled with the proximity of the United States, so that new technologies are available relatively quickly, meant that HTA could emerge as policy-relevant research to assist governments in spending public resources optimally, rather than as an adjudication mechanism between promoters of technologies and those expected to pay their costs.

The first Technology Assessment body in Canada was established in Quebec in 1988, following a gestation period initiated in the mid-1970s. The Conseil d'évaluation des technologies de la santé (CÉTS) was created by the Quebec government to promote, support, and produce assessments of health technologies, to counsel the Minister and all the key stakeholders of the health system. The impact of the CÉTS was documented (Reference Jacob and Battista20;Reference Jacob and McGregor21), and the CÉTS became the Agence d'évaluation des technologies et des modes d'intervention en santé (AÉTMIS), in 2000.

The national Canadian Coordinating Office for Health Technology Assessment (CCOHTA) was created in 1989 following an interprovincial symposium held in Quebec City (35). This followed studies of technology diffusion and calls in the mid-1980s to move ahead on health technology assessment (Reference Deber, Thompson and Leatt10;Reference Feeny, Guyatt and Tugwell15). Pan-Canadian efforts on nondrug technologies were, as in many other fields of primarily provincial jurisdiction, modestly funded, relatively low profile, and focused primarily on coordination so as to avoid offending larger provinces while capturing some of the “public good” aspects for the benefit of smaller provinces whose capacity was and remains limited. However, CCOHTA saw an important broadening of its mandate in recent years encompassing HTA, common drug review and optimal medication prescribing and utilization (Reference Sanders32). CCOHTA became the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) in 2006.

The British Columbia Office of Health Technology Assessment (BCOHTA) was established in 1990 by a grant to the University of British Columbia from the Province, to promote and encourage the use of assessment research by government, healthcare executives, and practitioners. It sought to examine more specifically the interactions of health technology with society. Government funding for BCOHTA ceased in 2002 when government made major cuts to its operating budget (Reference Kazanjian and Green23).

A Health Technology Assessment Program was established within the Alberta Department of Health in 1993 and then transferred to the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research in 1995. It was transferred to the Institute of Health Economics (IHE) in 2006 where it is currently situated (Reference Borowski, Brehaut and Hailey5;Reference Juzwishin22).

EVOLUTION OF HTA AND EMERGING TRENDS

HTA Organizations

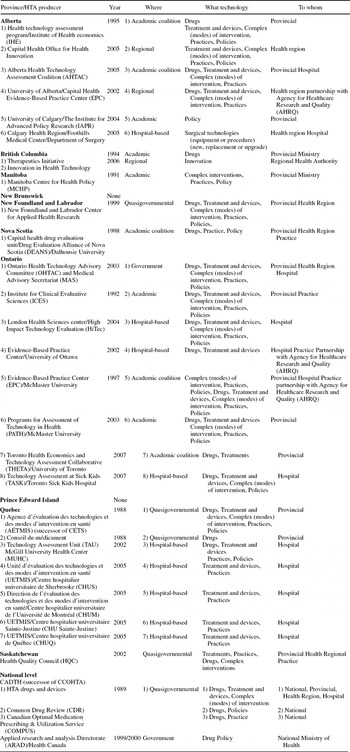

In addition to the growth in the number of HTA organizations, the culture of HTA has diffused relatively rapidly across Canada. Federal Commissions assessing the future of “Medicare” have generally recommended increasing resources for HTA and advised decision makers to increase the influence of HTA in decision making (Reference Kirby24;Reference Romanow31). Differences among provincial and territorial jurisdictions in delivering health services across Canada are reflected in the differences among organizations conducting HTA. As presented in Table 1, several models exist resulting from varying combinations of major affiliation, scope and breadth of the assessments, and targeted decision makers.

Table 1. Organizations Conducting HTA in Canada

HTA organizations can be supported by government (quasigovernmental), operate within government, develop within an academic setting or within a hospital. The quasigovernmental institution is a popular model in Canada. CADTH, AÉTMIS, The Health Quality Council in Saskatchewan (which succeeded the Health Services Utilisation and Research Commission), and the Center for Applied Health Research in New Foundland and Labrador are of this form. While funding of these organizations comes in the main from government, their margin of autonomy is important.

The Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee (OHTAC) is managed and staffed by government and the work plan is largely driven by hospitals and the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (Reference Levin, Goeree and Sikich26). OHTAC is currently leading several field evaluations of promising health technologies in partnership with clinical and academic research institutions.

Several academic centers have developed an important research capacity in Health Technology Assessment, among them the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) established in 1992 (19), and more recently, three Evidence-Based Practice Centers that conduct assessments in partnership with the Agency for HealthCare Research and Quality in the United States.

The emergence of hospital-based technology assessment efforts can be seen as evidence of the embedding of HTA as a permanent feature in decision making about health technologies in Canada. For example, the Greater Victoria Hospital Society introduced such a process in the early 1990s (Reference Juzwishin22), whereas Academic Health Centers in Quebec are now required to develop an HTA capacity (Reference McGregor and Brophy28).

Recent developments in Quebec highlight the increasing scope of the HTA effort, bringing both drugs and devices together and taking a broader view of “technologies,” with the proposed creation of INESSS (Institut national d'excellence en santé et en services sociaux). This effort is modeled in part on the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom, but the inclusion of social services is a novel extension of the effort to expand the influence of HTA and HTA-like efforts. Whether this represents a harmonious joining of related approaches remains to be determined, but it does suggest a maturation of the tools of HTA work.

Emerging Trends Shaping Technology Use and HTA

In 1994, one could reasonably conclude that, in all eight countries surveyed, HTA organizations were developing organizational structures and relations to health system actors that reflected the particular characteristics of each country's health system. The situation in Canada suggests that the evolution of HTA in Canada since that report has also been conditioned by the changes in Canada's approach to health policy, financing, and service provision, characterized as evolution amid constancy rather than radical change. HTA has clearly matured, as evident by its increasingly prominent role in government decision making as governments move, albeit by fits and starts, to strengthen their stewardship role and reduce direct engagement in allocation decisions. Health technology policy issues are now discussed at a National Health Technology Strategy Policy Forum. CADTH has also introduced an inquiry response service and liaison program, to facilitate the exchange of HTA information across its member provinces. This gradualism and continued growth in resource allocations to healthcare delivery may explain why Canadian consumers appear to have been largely unaware of the impacts of HTA.

From a system perspective, one of HTA's effects appears to have been “managed diffusion” of health technologies (Reference Kazanjian and Green23). By offsetting a politically acceptable delay to technology introduction with more information, and ensuring that the HTA process had the imprimatur of academic rigor, provincial governments as payers may have benefitted from falling unit costs available to later adopters (associated with increased production and competition from similar products) as well as risk mitigation by not being an early adopter (Reference Philips, Claxton and Palmer30). However, in the longer-term, a more reasoned approach to the introduction of innovation is becoming part of the decision-making culture in Canada.

For consumers, proximity to the United States has and continues to afford an alternative in two important ways: an object lesson in the perils of market-driven technology diffusion for those who favor the Canadian approach and a nearby, market-priced alternative for those who wish to exercise their consumer sovereignty more freely. Rapid shifts, perhaps driven by demographic pressure from the affluent, aging postwar generation, have yet to engender a move away from public financing. Should that change, many of the tools and insights of HTA, notably cost-effectiveness, which were new to government in the 1990s, would likely be adopted without comment by profit-motivated healthcare organizations as part of modern management of a complex healthcare enterprise. Any notion of societal discourse or contextualization process regarding health technologies will almost certainly be drowned out by what would likely be a vigorous debate about the merits of changing the foundational aspects of the Canadian healthcare system (Reference Lehoux, Tailliez, Denis and Hivon25;Reference Menon and Stafinski29).

The divergence between the policy response to pharmaceuticals and that to health technologies seems worthy of further investigation. The common drug review process, which is in part led by CADTH, in which all provinces except Quebec collaborate, has been markedly more developed than national-level collaboration in HTA more broadly (8). Among the factors that may explain this observation are a political response to a more concentrated industry presence (“pharma” is more clearly understood and better organized than “health technology industry”), readily discernible costs (drugs spending is relatively easily identified within provincial health spending), and the relative lack of complex “care production processes” involving pharma products as compared to technology more broadly, which makes cost-effectiveness calculations more straightforward for pharmaceuticals. Fairly or not, pharmaceuticals are typically perceived as “simple” and context-free interventions (i.e., patient takes pill) rather than complex interventions such as diagnostic imaging (i.e., patient has imaging study whose interpretation may trigger further technology use that unfolds over longer periods of time before definitive outcome occurs).

The future of HTA in Canada suggests a further deepening of its academic roots in applied health research as government decision makers have begun to embrace decision-making frameworks which incorporate primary data gathering (Reference Goeree and Levin16). This is a departure from a previous artificial separation of healthcare policy and publicly funded academic research. Indeed, there is potential in enhancing greater convergence between HTA organizations, funding organizations such as the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) and the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (CHSRF), public health, and the academically led evidence-based movement. Such a convergence would strengthen and increase training capacity in HTA.

Conditional reimbursement schemes have allowed public payers to satisfy consumer-driven (and manufacturer-driven) needs for access to new technologies while at the same time reducing the uncertainty in public policy decisions. Although a national health technology strategy has been developed and describes a coordinated approach to collecting further information through policy studies, its implementation will require the collective resolve of the provinces delivering health care.

CONCLUSION

Canada has been a vigorous supporter and user of HTA with a multiplication of HTA organizations across the country. HTA's influence has been most identifiable by means of the inputs of HTA organizations into the policy process at provincial government levels, but increasingly, hospitals are developing HTA competencies and capacity. Public engagement has been modest and the overarching policy environment of Canada's health system is such a significant determinant of the system's functioning and the use and diffusion of technologies that practitioners and individual providers have been relatively unengaged and arguably only indirectly affected by HTA. If HTA is to deepen its influence in the Canadian context, it will be essential to ensure that HTA is an active player in two forms of “linking-up.” The first of these is linking practitioners and providers to information, not only in the classic “evidence-based medicine/knowledge transfer” sense, but also with regular, even real-time, feedback on outcomes and comparative performance. The second is a form of health system “middleware” that can recraft the patient experience away from the current approach with silos of primary care, hospital, and long-term care to one with a more seamless transition of care, information, and yielding better outcomes and ideally, slowed cost growth. HTA's traditional policy-level focus in Canada will need to broaden to ensure its continued relevance, particularly if evolution amid constancy is replaced by dramatic change in the foundational aspects of Canada's health system.

CONTACT INFORMATION

Renaldo N. Battista, MD, ScD ([email protected]), Professor, Department of Health Administration, Université de Montréal, P.O. Box 6128, Station Centre Ville, Montreal, Quebec H3C 3J7, Canada

Brigitte Côté, MD, MSc ([email protected]), Adjunct Professor, Department of Health Administration, Université de Montréal, CP 6128, succ. Centre-Ville, Montréal, Quebec, H3C 3J7, Canada; Researcher, Agence d'évaluation des technologies et des modes d'intervention en santé (AÉTMIS), 2021 Union, Montreal, Quebec H3A 2S9, Canada

Matthew J. Hodge, MDCM, PhD ([email protected]), Adjunct Professor, Clinical Epidemiology & Biostatistics, McMaster University, 1200 Main Street West, Hamilton, Ontario L8N 3Z5, Canada

Donald R. Husereau, BSc, MSc ([email protected]), Director, Project Development, Department of Health Technology Assessment, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH), 600–865 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario K2S 5S8, Canada

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Robert Jacob, Donald Juzwishin, Arminee Kazanjian, and Louise Lafortune for their comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this study.