The emergence, and proliferation, of Islamist militant organizations, ranging from the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and Al-Shabbaab in Somalia, to Boko Haram in Nigeria and other parts of West Africa, has once again demonstrated that political Islam is an important global political issue. It has also highlighted a number of challenging, but increasingly crucial analytical questions: How popular a force is militant Islam, and how is it distinguishable from more conservative and moderate forms of Islamist activism? Does the rise of Islamist militancy across many regions of the Muslim world represent a “clash of civilizations,” or is its emergence a result of locally embedded, but globally linked, economic and social forces? And, finally, given the considerable diversity of socioeconomic formations within Muslim societies when, and under what conditions, do religious rather than ethnic cleavages serve as the most salient source of political identification?

Many arguments advanced in the context of the emergence of Islamist militant organizations across the globe have sought to answer these questions by invoking the economic underdevelopment of the Muslim world. The increasing permeability of state borders has transformed some economic grievances in the Muslim world into mistrust of Westernization and modern capitalism.1 And it is this hostility that has also brought about the emergence of Islamic banking, the expansion of Islamic charitable associations, and the use of informal banking systems, or hawwalat. These financial systems are used by Islamists not only to finance terrorist operations, but also to pursue a strict campaign of economic and “moral” separatism.2 In contrast, other analysts continue to downplay the long-term threat of Islamist militancy. They contend that, by and large, most Muslims are supportive of global markets, technological innovation, and capitalism in general.3

These interpretations capture important general truths about some of the causes and consequences of militant Islam. However, it would also be futile to address this challenge without understanding the locally specific social, economic, and political factors that help to sustain these movements. Black Markets and Militants sheds light on these issues by examining the economic and political conditions that have led to the rise of different forms of mobilization and recruitment of Islamist conservative and militant activists in three predominantly Muslim countries: Egypt, Sudan, and Somalia.

To understand the socioeconomic conditions under which recruitment into Islamist militant organizations occurs, it is imperative to understand when and under what conditions religious rather than other forms of identity become politically salient in the context of changing local conditions. This study centers on the current debate about the role that social and economic conditions play in giving rise to Islamist militancy and recruitment within the context of globalization.4 However, instead of emphasizing aspects of Islamic doctrine, pan-Islamist ideology, the impact of US foreign policy, or formal political and economic linkages with nation-states,5 I focus on the informal institutional arrangements that have resulted in the organization of Islamist conservative and militant organizations as well as ethnic-based political coalitions at the level of the community in three comparable countries.

Drawing on the results of over two decades of field research this work focuses on the informal market mechanisms that, under the exigencies of declining state capacity and state repression, have given rise to new forms of Islamist politics. To examine the ways in which different types of informal institutions serve to finance and organize Islamist militancy within the context of “weak” states, I explore the expansion of hawwalat, unregulated Islamic welfare associations, and the role of the Ahali, or private, Mosque in providing a conducive environment for the recruitment of young militants. The ultimate goal of this work is to play a modest role in enhancing global understanding about the relationship between political and economic change and Islamist movements generally and to broaden knowledge about which specific types of informal networks are (or are not) conducive to the rise of Islamist militancy and recruitment in particular local contexts.

Black Markets and Militants extends the boundaries of knowledge about the emergence of Islamist political activism and extremism by deepening our comparative understanding of the local and regional connections underpinning the evolution of political Islam. In this regard, I build upon the influential work of Judith Scheele and other scholars who have highlighted the crucial role that regional and transnational linkages play in the evolution of social and political life at the level of the community, and the ways in which, in the Middle Eastern and African contexts, Islam is often used to establish law and order even as it is mediated by different levels of state capacity or state repression.6 I do so by providing an analytical framework linking knowledge about political Islam with several important analytical debates in academic circles, including the literature on weak and fragile states in developing countries in general, and in Africa in particular; the varieties and political implications of informal institutions for overall patterns of social change and conflict; and the debate on terrorist finance and Islamist militant recruitment.

Global and Local Linkages in Islamist Politics

If this study addresses some important themes related to the long-standing concern among scholars of comparative politics with respect to the dynamics and evolution of Islamist and ethnic politics in African and Middle Eastern societies, it also has much to say with respect to the revived interest among scholars – across the disciplines – in the political and economic linkages between countries like Egypt, Sudan, and Somalia and the Arabian Gulf. In this respect this study has broader significance in that it explains the ways in which structurally similar relationships to the international and regional economy may help to produce very different political outcomes and generate variable forms of identity-based forms of collective action in three “most similar” cases. Egypt, Sudan, and Somalia are all major labor exporters that witnessed a boom in expatriate remittances in the 1970s and early 1980s. By the mid-1980s and into the 1990s, remittances declined dramatically, generating severe recessions and economic austerity policies. These capital inflows produced similar macro-institutional responses: in the boom, they circumvented official financial institutions and had the unintended consequences of undercutting the state’s fiscal and regulatory capacities while simultaneously fueling the expansion of informal markets in foreign currency trade, land, and labor. In the prosperous 1970s, these informal markets came to be “regulated” by indigenous Islamic and ethnic networks, which provided cohesion, shared norms, and an economic infrastructure outside the formal economic and political system. In the economic crisis of the 1980s and 1990s, however, the material links between formal and informal institutions eroded with the result that the nature of Islamist and ethnic politics transmuted again, producing three outcomes in Sudan, Somalia, and Egypt: consolidation, disintegration, and fragmentation.

More specifically, and through an in-depth historical analysis of comparable informal institutional arrangements, I demonstrate when, and under what conditions, informal market relations have oriented social and economic networks around religious networks as in Egypt and Sudan, or ethnic affiliations as in Somalia. I locate the rise and fall of an Islamist-authoritarian regime in Sudan, state disintegration in Somalia, and rising divisions and competition between conservative pro-market Islamist groups and militant Islamist organizations in Egypt in the way that informal financial and labor markets were captured by segments of the state and social groups. The divergent political outcomes in Somalia, Egypt, and the Sudan reflect – as I show in detail – the results of prior political conflicts between state elites and actors in civil society over the monopolization and social regulation (i.e., the creation) of different types of informal markets. My central argument is that the form identity politics evolved in the three cases was greatly dependent on whether Islamist or kinship groups were successful in establishing a monopoly over informal markets and relatively more proficient in utilizing their newly formed political coalition to control competition, albeit through highly coercive and violent means.

Labor Remittances and Islamist and Ethnic Politics

The larger comparative framework of Black Markets and Militants illuminates some pertinent issues related to the relationship between economic globalization, domestic political outcomes, and identity-based forms of collective action. In less-developed countries remittance inflows have a number of indirect impacts on local-level politics and the domestic economy.7 First, the internationalization of economic transactions in the form of labor remittances (as a percentage of imports) often coincides with the expansion of the informal financial sector and informal employment.8 Moreover, the vagaries of world market shocks, the boom and bust cycles, disproportionately impact domestic financial markets in the case of the labor exporters. Black markets for foreign currency, which operate on a relatively free market basis, open up the domestic financial markets to international forces.9 Second, in the context of weak states, increased economic globalization often leads to political conflict over trade and exchange rate policies that in many instances engender, in civil society, mobilization along regional, religious, and ethnic lines. As a consequence, state elites may meet these challenges with brutal reprisals and devastating human rights violations against groups in civil society. Third, the political power of capital, in relation to labor and the state, increases with internationalization, depending on the specific character of the informal economy. That is, whether the type of capital accumulation that results in its expansion accrues to formal state institutions or to private groups in civil society. Finally, the globalization of markets may either undermine state autonomy and the efficacy of its macroeconomic policies or strengthen its hand in terms of resource extraction and distribution.

Indeed, in Sudan, labor remittances from the 1970s until the late 1980s represented not only the most important source of foreign exchange for millions of Sudanese, they also posed a particularly significant threat for a new Islamist regime that sought to corner the market on these lucrative transfers. That most of these remitted funds bypassed official state channels and were essentially delivered directly to individuals and families meant that they had the potential of financing not only economic livelihoods but also altering state-society relations in crucial ways. Specifically, the role of informally channeled labor remittances had the potential of serving as key financing mechanisms of recruitment to groups working in opposition to the state. The newly ensconced Islamist-military junta led by Omer Bashir was particularly wary of this type of opposition and of the potential for the underground informal economy to provide a necessary financial base to the newly mobilized opposition. Moreover, because Bashir and the Islamist leaders inherited a heavily bankrupt and indebted state, they were keen to monopolize as many of these lucrative informal financial transfers as possible in order to strengthen their economic and political control of the country. The Islamists unprecedented violent crack-down on the black market, including numerous executions of people found guilty of economic treason, was also based on the fact that the Islamists of Sudan had themselves monopolized informal currency trade to build a strong financial base for their movement, recruit followers, and eventually capture the levers of state power. Their attack against the informal economy reflected personal experience.

In Somalia, as in Sudan, labor remittances have played a very important role, but the political consequence of these capital inflows resulted in a different political outcome. Here remittances and their transfer through informal hawwalat banking systems have played a major role in both the disintegration of the state and the financing of clan-based militias. Given the particular weak level of state capacity in Somalia and a distinct social structure wherein clan ties have served as the most important social institution in political and social life, informal financial transfers actually strengthened clan ties and helped to finance militias that were responsible for ousting the dictator Siad Barre. Moreover, following the collapse of the state, informal financial flows continue to ferment interclan conflict.

Egypt represents yet another comparative case wherein the oil boom in the Arab Gulf engendered a boom in labor remittance inflows of dramatic proportions. Like Sudan and Somalia, Egypt has long been a labor-exporting country and it counts the inflow of capital from migrant remittances as the most important source of foreign exchange. In the 1970s and 1980s Egypt followed a political economic trajectory similar to both Sudan and Somalia. Egypt was flush with remittances during the oil boom and much of this was funneled informally via black markets, bypassing the state and central banks. In many respects, this was considered a financial boom for the Islamist movement that took the opportunity to finance a host of businesses, social welfare associations, and money-changing institutions to support their movement and recruit followers. But the remittance boom also engendered an expansion of the country’s money supply that altered the very nature of Egypt’s informal economy. Specifically, remittances resulted in a boom of another sort centered on the rise and expansion of informal housing outside greater Cairo. Far from negligible, these informal settlements house millions of Cairo’s denizens and it is here that, in the 1990s, Cairo saw the rise in popularity of militant Islamism at the very heart of the capital.

The Politics of Informal Markets

This book thus examines the influence of labor remittance (i.e., informal commercial networks) in the evolution of Islamist and ethnic politics in Egypt, Sudan, and Somalia. This is not to neglect the importance of ideological and cultural factors as alternative explanations, but rather to explicate causal factors more precisely by highlighting the role of the informal, or more specifically the parallel, economy both as a measure of the diminished role of the state and as an arena through which domestic and international economies interact. This is because, while the literature on informal institutions has set the stage for dethroning the state as the primary unit of analysis, rarely have these studies advanced a truly political analysis of the informal realm that relates it to concrete patterns of state formation, state dissolution, democratization, and social mobilization in Africa and the Middle East.10 Fewer still have attempted to posit a linkage between informal financial markets and the global economy. More specifically, the important linkage between external capital flows and the informal market has not been analyzed sufficiently, with the result that its role in domestic political outcomes has been obscured.11 As Scott Radnitz noted in an important review of the literature on informality, despite important advances in the field, further research is required that takes seriously the role of informal institutions in political outcomes across difference cases, regime types, and levels of development.12 My comparative analysis of informality in Egypt, Sudan, and Somalia addresses some of these important concerns, and it goes further by focusing on the role of informal networks in the emergence of identity-based forms of collection.

A Typology of the “Hidden” Economy

Most work on informal markets in particular has remained largely descriptive as a by-product of the treatment of the state and the market as reified entities. Scholars concerned with the disrupting effects of state intervention focus on interventionist policies, while others inspired by the neutrality of the market are concerned primarily with barriers to market entry.13 Both views neglect the fact that there exists a plurality of state-society relations that structure markets within and across societies. Even those scholars who recognize the intimate link between the state and a particular type of informal market rarely recognize that the latter may function in close social proximity to other parallel, illicit, criminal, or otherwise unofficial markets. In the case of Somalia, for example, the expansion of the parallel market fueled a different type of informal market centered on livestock trade, which in turn facilitated the creation of an informal urban sector. Comprised primarily of family firms, the latter was thus not only dependent on remittance flows; it was forced to struggle to create a social structure to control competition and pricing behavior. That this development centered on extant clan structures in Somalia was due more to the newness of these informal firms and the absence of alternative financial institutions, rather than age-old emotional rivalries. Similarly, the relative success of the Islamists in Egypt and Sudan was in large part due to the Islamists’ monopolization of black-market transactions that negotiated an intimate link with official financial markets. Despite the fact that they represented a relatively small group, this strategy enabled the Islamist elite to establish a monopoly over informal finance and credit creating and utilizing their political coalition to control competition.14

Not only is it important to distinguish between the various analytical definitions of the hidden economy, it is equally important to treat these fragmented markets in a dynamic fashion. That is, how – and to what extent – are they created, in what manner are they related to state strength and local social structures, and finally on what state-initiated policies do their fortunes depend? For the parallel sector defined as highly organized foreign currency transactions, often denominated by dollars, situating these exchanges within the international as well as national economic context is analytically crucial.

In this respect it is important to differentiate between the official and this second, or hidden, economy and distinguish the various economic activities that can be observed within the latter category (see Figure I.1). Labor remittances accrue directly to millions back home, through informal, decentralized, and unregulated banking systems that are often, but not always, in contest with the state. As a consequence, one can expect that this type of external capital inflow has in most cases resulted in the rise of strong, autonomous private sectors and altered the socioeconomic landscape in a dramatic fashion.

Figure I.1 A typology of informal markets

The link between the expansion and political influence of the parallel market in Egypt, Sudan, and Somalia is critically tied to Gulf economies and consequently highly vulnerable to the vagaries of external economic shocks. The flexibility, efficacy, and the effects of the parallel market as linked to international boom and bust cycles and its relationship with the state have played an important role in political developments and, I argue, the emergence of different religious- and ethnic-based forms of collective action.

Informal Networks, Islamism, and the Politics of Identity

The question of when, and for what reasons, religious rather than ethnic cleavages serve as the most salient source of political mobilization in predominantly Muslim societies is more urgent than ever following the proliferation of a wide range of Islamist extremist groups and organizations in the Middle East and Africa. After all, the vast majority of Muslims interact without recourse to violence or militancy. Nevertheless, many noted scholars studying the rise of Islamist movements have persuasively pointed out the crucial role Islamic informal institutions play in promoting alternatives to formal political and economic institutions.15

However, even within Muslim societies the great bulk of the population is more likely to identify with different forms of Islam like Sufi or popular Islam as opposed to the conservative or extremist variety. Moreover, it is by no means evident that individuals and social groups in Muslim societies perceive “Islam” as the most significant form of political identification over that of family, clan, or ethnic group. This is especially true in the multiethnic societies of Muslim African countries, which until recently have been neglected in the analysis of Islamist movements. In fact, the scholarship on Africa suggests that the link between informal networks and the politicization of Islamist identity remains an open, empirical question since in the context of state failure and repression local actors tend to diversify their social networks to include both kinship and religious networks in order to consolidate efforts at income generation.16

In fact, while a large body of work on informal networks has highlighted their role in promoting a shared sense of cultural cohesion that can produce economic efficiency, many scholars have highlighted the “downside” of social networks.17 These scholars argue that, while social networks can provide an informal framework for greater economic efficiency and the provision of social services in lieu of the state, they can also operate as mechanisms of corruption and even promote clandestine networks, and protection rackets.18 Indeed, informal networks can be enlisted to support clandestine and militant activities. Moreover, since informal networks are often designed to further the material and ideological interests of individuals and groups, many who participate in an informal network know and trust each other, and these networks can be easily captured by the state or exploited for the purposes of more extremist resistance to state institutions.19 Consequently, rather than assuming a functionalist understanding of “social networks,” this book contributes to this debate by advancing an empirically researched comparative approach that distinguishes between various forms of informal networks and recognizes the ways in which they can form the bases for mobilization and recruitment into Islamist moderate and militant organizations, clan-led militias, and even pro-democracy social forces through the rearticulation of Islamic norms and practice.

This study also breaks with two common explanations of the causes of Islamist militant and terrorist recruitment. The first is largely an economic-centered literature that often downplays the role of Islamic norms in contemporary militancy.20 The second is the body of work that emphasizes the militant theology of certain aspects of Islamist intellectual traditions to the exclusion of socioeconomic and context-specific factors.21 Black Markets and Militants brings some very important new insights to this debate with respect to the question of why Islamist militants are successful in recruitment that highlight both normative and economic factors. First, from the perspective of their recruits, militant leaders often choose violence in order to improve the lot of their institutions and constituents by resisting state repression and gaining social and economic advancement. Second, the militants’ dissemination and enforcement of stringent Islamist norms is based on their own knowledge of the very specific needs of local residents, many of whom are undergoing severe social and economic crisis. Third, it is important to note that while militants may often enjoy a comparative advantage in certain forms of organized violence, their relative “efficiency” in this regard is context specific. That is, Islamist militants almost always come into conflict with other forms of authority including traditional clan and religious leaders (e.g., sectarian) and communities.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, social and economic factors underpin the process of recruitment in both conservative and extremist organizations. Though conventional scholarship routinely dismisses poverty and other economic and social factors in the analysis of the roots of extremism,22 I depart strongly from this line of argument. In Egypt the patterns of socioeconomic inequality – social exclusion, economic insecurity, and marginality – are key factors in fostering recruitment.23 To be sure, the leaders of many of these organizations represent the better educated middle class.24 However, what is often neglected in this observation is the fact that rank and file members are often younger and far less educated than those in leadership positions. Moreover, the potential pool of recruits more often than not hails from the ranks of the unemployed and underemployed. In this respect, they also represent a segment of the population that is the most vulnerable to socioeconomic crises and economic downturns. Understanding the content of local grievances enables us to gage not only who gets recruited, but also who is susceptible to recruitment in the future.

Understanding Islamist Activism: Distinguishing Islamism from “Terrorism”

A key problematic of much of the scholarship on violent extremism, much of it generated after the events of 9/11, is that it focuses on militancy or “terrorism” as its primary analytical objective. This obscures the very important fact that radicalization is a process and militancy – Islamist or otherwise – is often a militancy of last resort for the vast majority who join these organizations. The result is that this line of analysis suffers from a selection bias that routinely analyzes a small sample of relatively well-educated, middle-class actors engaged in terrorist operations. Moreover, in the case of the study of Islamist movements in particular, there is a scholarly consensus that Islamist activists are, by and large, middle class.25 This is too narrow of a formulation. Indeed, in order to uncover some of the roots of radicalization, we need to understand recruitment as a process whose success cannot easily be predicted based on a fixed set of motivations, social origins, or even a static Islamist ideological frame. Moreover, while scholars of extremism are correct to note “the poverty paradigm does not seem to prevail among Middle East extremist groups”26 in general terms, this should not obscure the fact that the lack of economic opportunity, and recessionary economies are often correlated with militancy.27

Another key issue related to the war on terrorism in general, and terrorist finance in particular, is the lack of distinction made between terrorism and Islamist forms of collective action. The conflation of Islamist politics with radical extremism in popular discourse and policy circles, in particular, is a major reason why anti-terrorist policies targeting terrorist groups espousing “Islamic” ideology have often proven counterproductive. As Martha Crenshaw has persuasively argued, violent organizations must be analyzed in the same terms as other political or economic organizations and, in this regard, terrorist groups are neither anomalous nor unique.28 In fact, some of the most recent work on terrorism increasingly focuses on internal dynamics and structures that are common to all terrorist organizations regardless of ideology.29 A notable example of this strand of scholarship is the work that argues that there is a potential link between the selective distribution of material resources and terrorism. This line of inquiry is useful in that it asks why certain types of groups are able to generate stronger commitment from their members than others. It suggests, in other words, that providing social services or public goods makes it possible for a terrorist or extremist group to ask more of, and demand greater sacrifice from, its followers.

However, a key problematic in this influential work is the lack of distinction made between radical political groups that utilize violence as part of their strategies and tactics, and Islamist forms of collective action that are conservative and often oppositional to domestic states, but are, in all other ways, distinct from radical political organizations such as Boko Haram, ISIS, or al-Qaeda. Indeed, Islamist political mobilization takes a number of forms and requires some analytical refinement. The most prominent include providing social welfare, contesting elections, and engaging in armed violence. As I show in subsequent chapters, the mix of these activities varies; some Islamists engage in only one type of activity, while others pursue two or all three of these activities. Some of the da’wa Islamists limit themselves to social welfare provision; the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood confines itself to social welfare and electoral contestation, while the Egyptian Islamic Group engages in armed violence.

What is important to note, however, is that the major trend of Islamism is nonviolent; it is best understood as an ideology that promotes an active engagement with and cultivation of Islamic beliefs and practices, both in the public sphere and in those activities traditionally considered private. Islamism, therefore, undeniably possesses a “political” component in that it seeks to transform public life in more Islamic directions. In reality, the rise of Islamic Welfare Associations (IWAs) over the last five decades is due in great part to globally induced economic change. More specifically, it is a result of the retreat of state-led social protection policies in the 1980s.30 The inability of many Muslim countries to fulfill their economic promises following a period of economic prosperity resulting from the oil boom in the Arab Gulf has inadvertently led to the expansion of informal networks and Islamic welfare institutions.31 In a pattern similar to the majority of less-developed economies, the resulting gap between expectations and reality in Muslim societies fostered among many a sense of disillusionment with both the ideologies and institutions of the secular state.32 To be sure, in the context of the diminished economic role of the state, there has been a rise of Islamist conservative social movements in many Muslim majority countries. But it would be a mistake to view all Islamists as fundamentally oriented toward overthrowing the political status quo or capturing the state. Such groups do exist, but they represent only a very small minority of a much larger social movement that espouses peaceful and nonviolent social and political change.33

In this study I take seriously the popularity of Islamism as representing a larger social movement rather than a militant fringe. This makes it possible to understand why Islamists have become increasingly concerned with supplying social protection to the region’s economically and socially vulnerable. Indeed, a major misconception in the anti-terrorist finance campaign pertaining to Islamic charities is the assumption that the latter function only to fulfill the religious obligation of Muslims and thus represent a small part of local economies. In reality, for the last fifty years, IWAs have played an important role in social protection and economic security for thousands in all Muslim countries. Whether by providing health care, education, job training and locating services, loans, or direct payments, IWAs have stepped in to fill many of the gaps created by a retreating welfare state. In addition, many Muslims view these activities as part of a moderate Islamist project of social transformation. In this respect, helping those vulnerable to poverty serves two purposes: it allows pious Muslims to meet their moral duty to aid those less fortunate, and it provides the venues through which they can employ the Islamist da’wa (Call to God) to spread their ideology and increase their membership.

Ultimately, however, this book is not exclusively an analysis of Islamist social movements. There is a rich literature on political Islam across the disciplines. These works have offered a sophisticated analysis of the ways in which Islam has been mobilized toward political objectives throughout the Muslim world.34 Rather, this book rests on the assumption that Islamist militant activism in Muslim societies has elements common to other extremist groups. Specifically, the organizational structures and recruitment methods are similar to other radical organizations in other parts of the world. However, what is specific to Islamist groups is the political and social context within which they operate. Many regimes in the Islamic world rely on political exclusion and repression to maintain rule. Under such conditions, many Muslims are forced to organize through informal networks to coordinate collective action through these channels. In some, but by all means not all, cases, these networks are captured by either conservative or militant Islamists who find themselves in violent confrontations not only with the state but also with many Muslims in their own society.

Finally, it is important to note that a number of scholars of Islamist activism and political extremism have correctly pointed to the role of the state, and in particular government repression, as increasing the propensity of individuals to join militant organizations in countries. However, whether these studies argue that state repression increases the propensity of militant recruitment or decreases the popularity of militancy or political Islam in general,35 they obscure the important fact that there are important variations of mobilization and that, in multiethnic and multireligious societies, actors may choose to join a host of different Islamist organizations or a variety of different ethnically affiliated insurgencies operating both in contest and parallel to the state.

Overview

If in the first part of Black Markets and Militants, I detail the similar political consequences of remittance inflows in all three of these labor-exporting countries during the boom, the second part of this book details the ways in which the onset of recession and the imposition of economic austerity measures resulted in divergent political developments in the three countries. I show how, in Sudan, Islamists were able to consolidate political power by effectively monopolizing informal financial markets: a development made far easier once they captured the levers of state power. In Egypt, the state imposed effective liberalization policies that undercut the financial power of the middle-class Islamist movement by strategically funneling remittances into official state channels. The unintended consequence of these policies was the further pauperization of millions of Egyptians living in the informal settlements outside the city. While most scholars have assumed that the “poor” in Egypt have not been a force in Islamist movements, I show here that this has not been the case. In fact, the economic insecurity and the economic downturns in the housing market and, by association, informally contracted labor, in Cairo laid the groundwork for militant Islamists to find a fertile ground from which to recruit many of the young men in these neighborhoods. For its part, Somalia, with the very weakest state capacity among all three countries simply disintegrated with the ensuing result of a rise in interclan conflict. In most of Somalia, capital inflows continue to be channeled through informal mechanisms utilizing primarily clan networks. What is interesting to note, however, is that in central Somalia, where no single clan has managed to monopolize the use of force, Islamist militancy has grown both as a response to the continued interclan violence and external actors who have intervened to stamp out militant Islamists and the potential of Islamist terrorism. To be sure, following the rise of militancy in Mogadishu, Somali militants have entered the fray in fighting to control and monopolize some of the hawwalat transfers. However, this has been an outcome rather than the cause of the rise of Islamist militancy in central Somalia. Only after a seismic shift in Islamist politics in the strongly divided central parts of the country have Islamist militants been able to fight for control, albeit unsuccessfully, over the trade in remittances. Ironically, Somali militants have benefited from the war on terrorist finance.

Black Markets and Militants then tackles two important questions directly related to the role of what is commonly termed “the black market” in the emergence of Islamist and clan politics in Egypt, Sudan, and Somalia. In contrast to other studies on informal institutions and Islamism I examine rather than assume “Islam” or “Jihadism” as the most salient source of political identity in the context of weakened state capacity. Moreover, rather than comparing “Muslim” societies I take seriously the religious and ethnic heterogeneity of the three countries. My primary aim is to explain when and under what contexts religious loyalties override other social cleavages in terms of their political salience and mode of recruitment. Throughout this volume, I also maintain that economic globalization, and specifically the inflow of remittances before and after the oil boom in the Gulf, has played an important role in delimiting the choices of state elites and thereby influencing domestic politics in Egypt, Sudan, and Somalia.

In these respects, this book departs from some conventional explanations of Islamist movements in three important ways. First, it takes seriously the role of globally induced economy factors in determining the political fortunes of both Islamist and ethnic politics in majority Muslim countries. Second, it differentiates in specific terms the economic factors underpinning conservative middle-class recruitment from its more militant counterpart. Finally, my study offers an explanation of why ethnic (or clan) cleavages may prove a more effective avenue of political organization over religious ties even in countries where many have assumed that Islam is the most “authentic” avenue of cultural identity and opposition to the state.

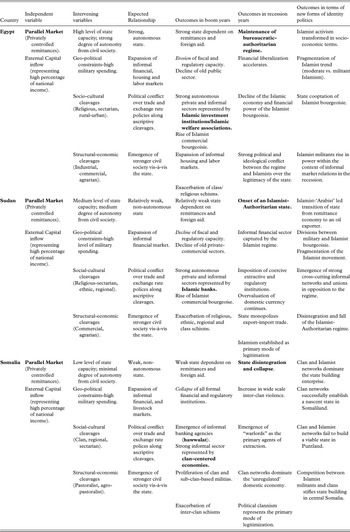

In this regard, the execution of Mahjoub Mohammed Ahmad for the crime of dealing in black-market transactions reflected a violent conflict between the state and groups in civil society over income generating activities unregulated and uncaptured by formal political authorities. As students of state formation have long noted, state building is crucially dependent on both the promotion and regulation of private economic activity. As a consequence, state builders, old and new, are often preoccupied with the capture of these rents for both the imposition of law and order, and the consolidation of political power. In the case of labor exporters, remittances – as the most important source of foreign exchange and revenue – became a source of economic competition, violent confrontation between state and civil society, and an arena where global economic forces intersected with domestic economies. As I show in the following chapters, the expansion of informal economic activities embedded in variable and locally specific social networks altered state-society relations in dramatic but divergent ways shaping new forms of identity politics. Table I.1 summarizes the expectations and outcomes in all three countries in the remittance boom years (1973–1983), and the recession years (1983–2019). It outlines the specific factors (or variables) highlighted in subsequent chapters that have underpinned variations in state-society relations over this period and thus determined the divergent political trajectories in Egypt, Sudan, and Somalia, respectively.

Table I.1 Egypt, Sudan, and Somalia: Outcomes in boom years (1973–1983), and recession years (1983–2019)

| Country | Independent variable | Intervening variables | Outcomes in boom years | Outcomes in recession years | Outcomes in terms of new forms of identity politics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egypt | Parallel Market (Privately controlled remittances). | High level of state capacity; strong degree of autonomy from civil society. | Strong state dependent on remittances and foreign aid. | Maintenance of bureaucratic-authoritarian regime. | Islamist activism transformed in socio-economic terms. |

| External Capital inflow (representing high percentage of national income). | Geo-political constraints-high military spending. | Expansion of informal financial, housing and labor markets. | Financial liberalization accelerates. | Fragmentation of Islamist trend (moderate vs. militant Islamism). | |

| Socio-cultural cleavages (Religious, sectarian, rural-urban). | Strong autonomous private and informal sectors represented by Islamic investment institutions/Islamic welfare associations. Rise of Islamist commercial bourgeoisie. | Decline of the Islamic economy and financial power of the Islamist bourgeoisie. | State cooptation of Islamist bourgeoisie. | ||

| Structural-economic cleavages (Industrial, commercial, agrarian). | Expansion of informal housing and labor markets. | Strong political and ideological conflict between the regime and Islamists over the legitimacy of the state. | Islamist militants rise in power within the context of informal market relations in the recession. | ||

| Exacerbation of class/religious schisms. | |||||

| Sudan | Parallel Market (Privately controlled remittances). | Medium level of state capacity; medium degree of autonomy from civil society. | Relatively weak state dependent on remittances and foreign aid. | Onset of an Islamist-Authoritarian state. | Islamist-‘Arabist’ led transition of state from remittance economy to an oil exporter. |

| External Capital inflow (representing high percentage of national income). | Geo-political constraints-high level of military spending. | Decline of fiscal and regulatory capacity. Decline of old private-commercial sectors. | Informal financial sector captured by the Islamist regime. | Divisions between military and Islamist bourgeoisie. Fragmentation of the Islamist movement. | |

| Social-cultural cleavages (Religious-sectarian, ethnic, regional). | Strong autonomous private and informal sectors represented by Islamic banks. Rise of Islamist commercial bourgeoise. | Imposition of coercive extractive and regulatory institutions. Overvaluation of domestic currency continues. | Emergence of strong cross-cutting informal networks and unions in opposition to the regime. | ||

| Structural-economic cleavages (Commercial, agrarian). | Exacerbation of religious, ethnic, regional and class schisms. | State monopolizes export-import trade. | Disintegration and fall of the Islamist-Authoritarian regime. | ||

| Islamism established as primary mode of legitimation | |||||

| Somalia | Parallel Market (Privately controlled remittances). | Low level of state capacity; minimal degree of autonomy from civil society. | Weak state dependent on remittances and foreign aid. | State disintegration and collapse. | Clan and Islamist networks dominate the state building enterprise. |

| ExternalCapital inflow (representing high percentage of national income). | Geo-political constraints-high military spending. | Collapse of all formal financial and regulatory institutions. | Increase in wide scale inter-clan violence. | Clan networks successfully establish a nascent state in Somaliland. | |

| Social-cultural cleavages (Clan, regional, sectarian). | Emergence of informal banking agencies (hawwalat). Strong informal sector represented by clan-centered economies. | Emergence of “warlords” as the primary agents of extraction. | Clan and Islamist networks fail to build a viable state in Puntland. | ||

| Structural-economic cleavages (Pastoralist, agro-pastoralist). | Proliferation of clan and sub-clan-based militias. | Clan networks dominate the ‘unregulated’ domestic economy. | Competition between Islamist militants and clans stifles state building in central Somalia. | ||

| Exacerbation of inter-clan schisms | Political clannism represents the primary mode of legitimization. |