And I would be the first to say that I am still committed to militant, powerful, massive, non-violence as the most potent weapon in grappling with the problem from a direct action point of view. I'm absolutely convinced that a riot merely intensifies the fears of the white community while relieving the guilt. … But it is not enough for me to stand before you tonight and condemn riots. It would be morally irresponsible for me to do that without, at the same time, condemning the contingent, intolerable conditions that exist in our society… . And I must say tonight that a riot is the language of the unheard.

– Martin Luther King, 14 March 1968 (King Reference King1968)Riots work. And I've never said it in that way before. I am an American because of a riot. The [Boston] Tea party is sold to us from the time we are kindergarteners to the time we graduate high school – we are told that Americans and patriots got so fed up with paying taxes to the crown that they decided to burn some shit to the ground… . Post-riots, they have two new black city council members, they have actual advocates in the community now, and the police chief retired. So if it was argued that riots worked for Ferguson, absolutely they did.

– Killer Mike, 6 August 2015 (Kreps Reference Kreps2015)Very few people defend rioting as a justified political action. Political opponents point to riots to delegitimize the political movement that instigated the violence. Even supporters of a political cause quickly condemn protests when they become riots. Consider, for instance, the reaction of prominent figures to the April 2015 anti-police brutality riots in Baltimore. Baltimore resident, and co-creator of HBO's The Wire, David Simon issued a statement as the riots were ongoing that read in part ‘If you can't seek redress and demand reform without a brick in your hand, you risk losing this moment for all of us in Baltimore. Turn Around. Go home. Please’ (Taintor Reference Taintor2015). President Obama expressed similar sentiments when he said, ‘One burning building will be looped on television over and over and over again, and thousands of demonstrators who did it the right way, I think will be lost in the discussion’ (Davis and Apuzzo Reference Davis and Apuzzo2015). Both of these statements share a common concern that riots run the risk of undermining political progress that is more effectively achieved through non-violent means.

More radical thinkers have been quick to push back against condemning riots as ineffective. For instance, George Ciccariello-Maher refuted the claim that rioting only encouraged a political backlash (Reference Ciccariello-Maher2015). Ta-Nehisi Coates argued that calls for the Baltimore rioters to protest peacefully in the face of violent repression by the Baltimore Police Department were hypocritical (Reference Ciccariello-Maher2015). Hip hop artist Killer Mike defended the anti-police brutality rioters by arguing that riots were an effective tool for bringing about political change – a view that was echoed in subsequent political analysis (Friedersdorf Reference Friedersdorf2015a; Friedersdorf Reference Friedersdorf2015b; Kreps Reference Kreps2015; Lopez Reference Lopez2006). These commentators argue that while riots may not be ‘wise’ or ‘correct’ (Coates Reference Coates2015), they were a last resort after community members had tried and failed to gain redress for their grievances using non-violent means. In every instance of recent anti-police rioting in the United States, the political authorities responded to some of the rioters' key demands.Footnote 1 Yet these defenders focus on riots' effectiveness rather than its legitimacy. They do not defend rioting on normative grounds.

The lack of normative theorizing in academic scholarship about riots is even more striking. There is an extensive literature in history, sociology, and empirical political science about riots and rioting. Historians have a long tradition of interpreting the changing meaning and significance of riots over time and across cultures (Rudé Reference Rudé2005; Thompson Reference Thompson1971). Political scientists and sociologists have also explored the causes of riots as well as policies to minimize and prevent them (Graham and Gurr Reference Graham and Gurr1979; Tilly Reference Tilly1976; Tilly Reference Tilly1983; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2009). Yet there is very little normative scholarship about riots.Footnote 2

There are, however, significant bodies of literature about other forms of political violence and militant resistance. For example, a long tradition in political theory, stretching back to the early modern era, considers the justifications for revolutions and resisting rulers (Finlay Reference Finlay2015; for example, Locke Reference Locke and Laslett1988; Marx and Engels Reference Marx, Engels and Moore2015). Political theorists have also written normative defenses of terrorism (for example, Held Reference Held, Frey and Morris1991; Nielsen Reference Nielsen and Leiser1981). The political obligation literature spells out the conditions under which citizens may resist state authority (Delmas Reference Delmas2014; Klosko Reference Klosko2005; for example, Pitkin Reference Pitkin1965). The just war tradition explores both when a war is justified and what is appropriate conduct in a war (for example, Coady Reference Coady2008; Walzer Reference Walzer2006).Footnote 3 Scholars of civil disobedience have elaborated on the conditions under which citizens may intentionally and publicly break the law (for example, Celikates Reference Celikates2016; Markovits Reference Markovits2005; Morreall Reference Morreall1976; Scheuerman Reference Scheuerman2015; Zinn Reference Zinn2014).

While riots are similar to these other political phenomena, they are distinct in some crucial ways. First, riots are worthy of attention in their own right. Secondly, riots are not the same as revolutions: revolutions seek to replace the entire system of government with a new system, whereas riots are very localized protests of specific grievances. Thirdly, riots are not the same as civil disobedience or conscientious objection; in these cases, the law breaker intends to be convicted as part of the protest, whereas rioters often attempt to avoid arrest.

Only radical and Marxist scholars take riots seriously (Clover Reference Clover2016; Fanon Reference Fanon1963; Lenin Reference Lenin1975; Sorel Reference Sorel and Jennings2002). Yet even they do not develop a normative defense of rioting. They usually characterize normative questions as bourgeois moralism, and instead focus on riots’ ability to bring about revolutionary change. The lack of normative theorizing about riots is doubly surprising given the analytical focus on riots in more empirically oriented fields, and the amount of attention devoted to other forms of political protest, violence and resistance in political theory.

This essay explores why there is no just riot theory tradition in Western political theory. I argue it is because riots are extra-institutional in four ways (1) they are extra-public because rioting crowds self-organize (they are not formally institutionalized groups such as parties or social movements); (2) they are extra-state because rioting disrupts the state's monopoly on violence; (3) they are extra-legal because they involve breaking laws concerning public assembly; and (4) they are extra-parliamentary because rioters express their grievances outside of normal political processes. For instance, Britain's Public Order Act defines a riot as follows:

Where 12 or more persons who are present together use or threaten unlawful violence for a common purpose and the conduct of them (taken together) is such as would cause a person of reasonable firmness present at the scene to fear for his personal safety, each of the persons using unlawful violence for the common purpose is guilty of riot (1986 emphasis added).

Two key parts of this definition – the presence of twelve or more persons and the use or threat of unlawful violence – highlight two of the four essential features of a riot outlined above: riots are crowd actions and involve violence. The first two sections will consider these two forms of extra-institutionality in turn: they explore what could justify political action outside of normal democratic procedures and what could justify the use of violence. Yet even if both of these aspects of riots' extra-instituionality are justified, there are still crucial questions about their extra-legality and tendency to operate outside of normal parliamentary procedures (the third and fourth characteristics described above). These questions will be addressed in the third and fourth sections. In the conclusion I argue that because each of the four elements of a riot that is normally deemed illegitimate has well-theorized instances in which legitimate exceptions are made, there is no reason in principle that a theory of a just riot is not possible. The four types of extra-institutionality thus suggest possible criteria that could justify a riot.

The Crowd as an Extra-Public Actor

The crowd has an ambiguous place in the history of political theory. McLelland observes that ‘[i]t could almost be said that political theorizing was invented to show that democracy, the rule of men by themselves, necessarily turns into mob rule’ (Reference McClelland1989, 1). Political theory's bias against the crowd revolves around two main arguments. First, the elitism of most canonical political thinkers made them suspicious of crowds for lacking the expertise and leadership for effective political action. Secondly, more populist theorists suspected crowds of being too disorganized to be capable of sustained political action.

An early example of the first tendency is Plato's critique of democracy in The Republic. He worried that the people were not temperamentally suited to govern, and that demagogues would manipulate the masses into establishing a tyranny (1992, 565 d-e). Hobbes expressed a different concern. He drew a sharp distinction between the people and the crowd. ‘A people is a single entity with a single will; you can attribute an act to it. None of this can be said of a crowd’ (Reference Hobbes, Tuck and Silverthorne1998, 137). According to Hobbes, the crowd only exists in a state of nature. Only a crowd can carry out a rebellion. When a rebellion takes place, the individuals participating cease to be people, and turn into a crowd; the crowd returns the people to a state of nature (Reference Hobbes, Tuck and Silverthorne1998, 76). Whether the crowd leads to tyranny (as with Plato) or to anarchy (as Hobbes maintains), both lines of thinking agree that the crowd is unruly and prone to facilitating dangerous political outcomes. Even radical pluralist thinkers such as Arendt endorse this interpretation of crowds. In her analysis of the Dreyfus Affair, she distinguishes between the mob – a proto-fascist, extra-institutional mass movement prone to anti-Semitism and violence – and the people – a deliberative public, capable of resisting mob rule through political action (Arendt Reference Arendt1973, 106–120). This historical distinction between demos, multitude, crowd and mob, on the one hand, and ‘the people’ on the other hand shares the belief that an institution must mediate between the masses and the government. Without a mediating institution, prior political theory maintains that the masses will either prop up a tyrant or promote anarchy.

More radical and populist theorists worry that the crowd is too disorganized to be capable of effective political action. For example, Lenin argued that riots constituted the proletariat's spontaneous resistance to capitalism (Reference Lenin1975, 36). He chastised socialists who celebrated spontaneous acts by the working class because ‘the spontaneous development of the working–class movement leads to its becoming subordinated to the bourgeois ideology’ (Reference Lenin1975, 49). According to Lenin, the crowd was incapable of accomplishing anything without the institution of the party.

In reflecting on her experiences in the Occupy Wall Street movement, Dean makes a similar argument. Left-wing social movements since the 1960s, such as Occupy, reveal a split between ‘mob or people’. Dean argues that ‘[t]he individualism of [Occupy's] democratic, anarchist, and horizontalist ideological currents undermined the collective power the movement was building’ (Reference Dean2016, 4). She asserts that the collective will of the crowd can only be transformed into political power through a political party (Reference Dean2016, 28). These thinkers argue that institutions such as the party turn the disorganized crowd into a people, and transform the crowd's grievances into clearly articulated demands that can lead to political change.

While many theorists characterize the tumult generated by crowds as creating division in the polity, a counter-tradition celebrates disorder as a means of preserving freedom. In The Discourses, Machiavelli observes ‘those who damn the tumults between the nobles and the plebs blame those things that were the first cause of keeping Rome free, and that they consider the noises and the cries that would arise in tumults more than the good effects they engendered’ (Reference Machiavelli1996, II.4.2 (p. 16)). His point is that tumults – mass popular disturbances including riotsFootnote 4 – serve as an extra-institutional check on elites’ power and ambition that is needed to preserve the freedom of the republic (Reference Machiavelli1996, I. 4 p. 17).

According to Canetti, the crowd creates perfect equality through processes of de-individuation. Many classic crowd theorists describe the crowd as dangerous because it unleashes ‘animalistic’ and ‘primitive’ behaviors that are normally repressed by society (Freud Reference Freud1793; LeBon Reference LeBon1896; McClelland Reference McClelland1989, 248–249). In Crowds and Power, Canetti upends this traditional understanding of the crowd in several ways. While not denying its potential for violence, or its vulnerability to manipulation by a leader, he develops a theory of the crowd as fundamentally egalitarian and as the first source of justice. Canetti argues that ‘[a]ll demands for justice and all theories of equality ultimately derive their energy from the actual experience of equality familiar to anyone who has been a part of the crowd’ (Reference Canetti1984, 29). Crowds, in Canetti's theory, are ontologically distinct from individuals. When an individual joins a crowd, they lose themself and experience a sense of de-individuation. This de-individuation creates a radical equality and erases the numerous hierarchies through which societies maintain order (Reference Canetti1984, 18).Footnote 5 Canetti develops an elaborate typology of crowds to push back against the tradition in Western political thought that views the crowd as always prone to demagoguery and violence. His typology generates 280 distinct types of crowds (Reference Canetti1984, 29–63; McClelland Reference McClelland1989, 302). While Canetti does not directly discuss rioting, his theory identifies three virtuous traits of the crowd: its state of pure equality, its ability to issue demands outside of formal institutions and its temporary undermining of social hierarchies.Footnote 6 His nuanced account of the crowd recognizes both its potential for destruction and its capacity for justice.

Finally, in contrast to many who argue that there can be no moral order in crowds (Arendt Reference Arendt1973, 106; LeBon Reference LeBon1896), several defenders of crowds have noted the orderliness of riots (Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm2017, 6; Marx Reference Marx1970, 27–28; Rudé Reference Rudé2005, 49–51; Thompson Reference Thompson1971, 77–79; Tilly Reference Tilly1983; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2009, 331–336). Empirical studies of riots note the tendency of crowds to self-police. Rioting crowds tend to act in a manner that is commensurate with the grievance that triggered the event. The crowd's activity is neither ‘capricious nor random’ (Gilje Reference Gilje1999, 7).Footnote 7 In eighteenth century England, crowds frequently protested against price gouging by ‘raising a mob’ to visit the local farms and estates of the wealthy and demand that grain be sold to the poor at a reasonable price. Thompson notes how orderly such a crowd was in both the articulation of its grievance and its willingness to pay for the grain, so long as it was at a price the poor could afford (Reference Thompson1971, 107–115). Workers, prior to the recognition of collective bargaining rights, would use mass protest to increase wages and protest high prices. Crowds of ‘Luddites’ destroyed machinery to protect their jobs (Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm2017, 6, 1952). Historians of crowd behavior have long demonstrated that crowds have their own ‘moral economy’ (Thompson Reference Thompson1971) whereby mass protest is motivated by a norm violation by the authorities. Crowds tend to behave well in protests, limiting their actions to the target of their grievances, and are generally proportional in their responses to those grievances.

The conventional reason for rejecting the crowd as a legitimate political actor is that it is irrational and does not operate through rational and deliberative institutions. Throughout the history of political theory (from Plato to Arendt) and across the ideological spectrum (from Hobbes to Lenin) there has been a strong fear of the dangers of mob rule. The crowd either promotes anarchy or tyranny, or it is too disorganized to rule effectively. When we evaluate the counter-traditions that defend crowd action, however, we find four criteria by which we can assess whether a rioting crowd is behaving justly or unjustly. First, following Machiavelli, one key question to ask is Are the crowd's actions freedom preserving? Secondly, following Canetti's defense of the crowd as a field of equality, a key question to ask is Do the crowd's actions promote equality? Thirdly, in the tradition of historians and sociologists of crowd behavior such as Hobsbawm, Rudé, Tilly and Gary Marx, a key question to ask is Do the crowd's actions give voice to the grievances of marginalized groups? Fourthly, following Thompson, a key question to ask is Are the crowd's actions orderly and self-policing? If an assessment of a crowd returns an answer of ‘yes’ to all four questions, it is not promoting tyranny (a key concern of elitist crowd critics), and it is certainly acting in a concerted way to bring about a political end (a key concern of populist crowd critics). While these considerations alone are not sufficient to justify a riot, they are necessary criteria to justify a rioting crowd's actions.

How Does a Riot Violate the State's Monopoly on Violence?

In practice, the violenceFootnote 8 in riots tends to take three forms: (1) physical attacks on other people, (2) vandalism of property (both public and private) and (3) looting, which generally takes the form of rioters stealing goods from stores. This violence immediately raises two questions. First, why (and when) is violence bad? Secondly, what could possibly justify these acts of violence by rioters?

Because riots are violent political acts, they have an uneasy relationship with Western political theory tradition's normal understanding of violence. Frazer and Hutchings (Reference Frazer and Hutchings2007; Reference Frazer and Hutchings2009; Reference Frazer and Hutchings2011a; Reference Frazer and Hutchings2011b) observe that the dominant thinkers in the Western tradition perceive violence as related to politics instrumentally – either as a means to achieve political ends (Clausewitz 1968; Machiavelli Reference Machiavelli, Skinner and Price1988; Weber Reference Weber, Owen and Strong2004) or as antithetical to politics (Arendt Reference Arendt1970; Rawls Reference Rawls1999). They also identify a counter-tradition that treats violence as creative and expressive. These theorists view violence's role in politics as either expressive or constitutive of character and community (Benjamin Reference Benjamin and Demetz1978; Fanon Reference Fanon1963; Sorel Reference Sorel and Jennings2002).Footnote 9 If we consider both the dominant and counter-narrative positions on the relationship of violence to politics, the idea of a just riot does not fit well into any of these categories. This is most obvious in Arendt's position, which maintains that the riot, because it is violent, is difficult to justify and impossible to legitimate (Reference Arendt1970, 52).Footnote 10

In the more conventional reading of violence as a means to achieve specific ends, a crucial issue is who may legitimately wield the instruments of violence? Normally the state reserves that privilege for its agents, due to the fear that if just anyone is allowed to use violence to achieve their political ends, then the state's monopoly on violence breaks down. From this perspective, the state must keep the riot beyond the pale in order to maintain order. Conversely, the counter-narrative tradition of violence and politics eschews questions of justification altogether. In this reading, the riot might be expressing the grievances of the rioter, or perhaps even constitute a new political entity (Canetti Reference Canetti1984) or be useful for fashioning a new sense of self (Fanon Reference Fanon1963). However, these political theorists do not consider the riot through the framework of justification.

Critics of riots point to acts of violence committed by rioters as justification for condemning the riot. Could anything redeem this violence? The social contract tradition suggests that two criteria – which I call the grievance criteria – justify using violent means to resist or overthrow the government. Since rioting is less of a threat to the state's authority than an armed insurrection or revolution, anything that would justify those more significant transgressions of state authority would also justify rioting. In order for the violence of the riot to be justified, the rioters must be motivated by a significant enough grievance that it justifies their use of violent protest.

The first grievance criterion follows from the Lockean tradition of revolution. The revolution and resistance tradition recognizes that if a government violates the rights or welfare of its citizens, then the people have a right to resist and replace it with a new one (Locke Reference Locke and Laslett1988, 225).Footnote 11 More contemporary theorists also recognize a similar right. Rawls identifies a right of militant resistance when conditions under the basic structure are unjust (Reference Rawls1999, 323), but does not fully state what would constitute such an injustice.Footnote 12 While it is difficult to spell out how severe a violation of the basic structure justifies resistance, one criteria for justifying a riot on these grounds is whether or not the polity systematically violated one of the constitutional triad of democracy, human rights or the rule of law. As these constitute the basic structure of a just liberal society, a polity that protects these basic structures with respect to its citizens creates a coercive relationship between citizens and the state, negating the legitimacy of the state's monopoly on violence.

Not all injustices involve violations of fundamental civil and political rights. Shelby draws upon Rawls' standard of ‘intolerable injustice’ to defend disobedience to the state. He notes, however, that Rawls never specifies what that limit is (Reference Shelby2007, 145). Shelby suggests that the standard should be a duty of self-respect, which is fulfilled by affirming one's equal moral worth as a person. When a society systematically violates the self-respect of a portion of its population, such as poor urban blacks in the United States, then there is a legitimate reason to protest and resist injustice. Shelby defines deviance as ‘sharply divergent from widely accepted norms’ (Reference Shelby2007, 128) and lists crime, refusing to work in legitimate jobs and having contempt for authority as examples of deviance. Gary T. Marx draws a similar distinction between two kinds of deviance – nonconforming and aberrant. Nonconforming deviance is ‘a thrust towards a new morality’ (Reference Marx1970, 24) and violates existing norms with an aim ‘to replace them with new norms’ (Reference Marx1970, 24). Conversely, aberrant behaviour ‘deviates out of expediency and for the momentary gratification of personal ends without seeking social change’ (Marx Reference Marx1970, 24).Footnote 13

These non-civil and political justifications for resistance point to a second potential criterion for justifying a riot. Rioting is certainly a deviant behavior, but if the riot involves non-conforming deviance (as, for instance, with the Stonewall riots contesting the anti-LGBT policies of the New York police), or if it expresses contempt for the authority of a social and economic system that does not afford the basic minimum required for self-respect (as in the 1960s inner city riots in the United States), then these types of deviance point towards legitimate grievances. The second grievance criterion that justifies a riot is thus: Does the polity systematically fail to guarantee conditions of reciprocity to its most disadvantaged members?

What kind of violence within a riot could be legitimate? Even a just grievance does not permit just any type of violence in a riot. A riot could be just if it is in response to political authorities’ systematic violation of the rights of the rioters, but the rioters’ actions would be unjust if the violence was not proportional to the oppression the rioters were confronting, or if it did not target those responsible for the grievance. The three types of violence in a riot – violence against persons, vandalism and looting – all have acceptable and unacceptable targets. If rioters use violence in self-defense, either against police dispersing a just protest or against the targets of their grievances, then this form of violence may be justifiable (cf. Brennan Reference Brennan2016). Conversely, if the rioters target innocent bystanders or use the riot to target individuals who did not act violently against them, then the use of violence cannot be justified. Similar criteria would be applied to vandalism. Attacking police equipment or property in a violent street clash might constitute a legitimate target, but targeting bystanders’ personal property can never be justified. Finally, looting could be justified if the rioters use it to redress an economic injustice, as in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century food riots or the survival looting undertaken by the residents of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.

The first two forms of extra-institutionality that we have surveyed are essential to all riots. In order for a gathering to be considered a riot, it must be a mass public demonstration and it must be violent – either against property or against people. Even if a riot has a crowd that is promoting freedom and equality, enabling marginalized groups to articulate their demands, and the crowd's behavior is self-policing, and even if the violence is proportional and aimed at legitimate targets, it does not follow that the reason for the riot is justified, or that rioting in this instance is a reasonable tactic.

Not all (or even most) riots are driven by grievances. People riot to celebrate sports victories, or to persecute marginalized groups. People riot when the state's police power is withdrawn (such as during a police strike or breakdown in civil order). In none of these cases is a grievance present. Yet even if there is a legitimate grievance, one must first determine if other – non-violent and normally legitimate – means of redressing it are possible. The need for a legitimate grievance relates to the riot's extra-legality. The requirement to exhaust legitimate means of redress points to the riot's extra-parliamentarianism. I next consider each of these in turn.

How is a Riot Extra-Legal?

A riot is extra-legal because it breaks the law against rioting. Both the riot and unlawful assembly are forms of public assembly that disturb the peace through noise and violence. Statutes that prohibit disturbing the peace criminalize public assembly. State authorities have long used such statutes to target political protestors across the political spectrum, as they are written and enforced in a way that gives police forces great discretionary power to interpret ongoing and potentially future acts as violent and threatening the public (Inazu Reference Inazu2017, 5–6).

There are three important aspects of the connection between rioting and unlawful assembly. First, a riot is a form of public assembly that turns violent. Secondly, state authorities can use riot laws to restrict legitimate protest.Footnote 14 Thirdly, the use of unlawful assembly and riot laws to arrest and charge protestors has a chilling effect on risk-averse citizens. For these reasons, we should not automatically assume that if protestors are charged with rioting or unlawful assembly that their actions are illegal. Local authorities’ power to treat a protest as a riot means that state officials may delegitimize many legitimate protests as part of their policing and efforts to control dissent.

Political theorists generally recognize that citizens are obliged to obey the law. Four general traditions uphold this obligation: the voluntarist position, the utilitarian position, the fairness position and the morality of law position (Green Reference Green and Zalta2012; Hyams Reference Hyams and McKinnon2012, 11; Smith Reference Smith1972, 953). All four traditions acknowledge exceptions to this obligation. Rawls, for instance, argues that ‘once society is interpreted as a scheme of cooperation among equals, those injured by serious injustice need not submit’ [to the law] (Reference Rawls1999, 336). Locke maintains that if the government violates the social contract by threatening its citizens' rights to life, liberty or property, then the citizens may legitimately overthrow the government (Reference Locke and Laslett1988, 412–413). Bentham argues that when the law no longer maximizes the utility of a country's citizens, then citizens can disobey the law (Reference Bentham and Harrison1948, 55).Footnote 15 And Raz argues that the government and the law ‘is legitimate to varying degrees regarding different people’ (Reference Raz1986, 104) and that ‘disobedience to law is sometimes justified’ (Reference Raz1986, 101). Every tradition of political obligation recognizes that individuals may disobey unjust laws, and may engage in acts of resistance against unjust regimes. Even Hobbes, the thinker most famously associated with the absolute and unlimited authority of the sovereign, recognizes ‘the Liberty to disobey’ the sovereign when he or she threatens the individual (Reference Hobbes and Tuck1996, 151).Footnote 16

Although theorists recognize some forms of justifiable law breaking, how the law is broken matters just as much as the fact that it can be broken. Political theorists recognize at least six different types of principled law breaking as having justifiable exceptions to obedience to the law: (1) testing the law,Footnote 17 (2) civil disobedience,Footnote 18 (3) democratic disobedience,Footnote 19 (4) disruptive disobedience,Footnote 20 (5) whistleblowingFootnote 21 and (6) deviance.Footnote 22 There are crucial differences between rioting and most of the above forms of justified law breaking. First, the first four cases involve an individual consciously breaking a specific law because it is unjust: the law itself is immoral. Deviance contests the unjustness of the entire system by breaking laws that are not necessarily unjust in and of themselves. Conversely, the rioters are contesting the legal limits of public protests. They do not generally riot against laws on rioting. When they riot on grievance grounds, they are contesting some other perceived injustice. Rioting may be conscientiously motivated if it is a grievance riot. The first four forms of resistance listed above must be conscientiously motivated for the law-breaking act to be legitimate. Many forms of rioting are not, but that would be a basis for testing a riot's legitimacy. Deviance is the sole exception to this conscientiousness test, as Shelby tends to frame justified deviance as necessitated by conditions of intolerable injustice – that is, because the system itself is manifestly unjust, those who are disadvantaged by it no longer have an obligation to abide by its laws (Reference Shelby2007, 155).

Scholars generally recognize justified law breaking if the illegal action is contesting a greater injustice (Celikates Reference Celikates2016, 43; Edyvane and Kulenović Reference Edyvane and Kulenović2017, 1361; Markovits Reference Markovits2005, 1898; Rawls Reference Rawls1999, 319; Scheuerman Reference Scheuerman2015; Shelby Reference Shelby2007, 127). Edyvane and Kulenović argue that law breaking is ‘justified when it functions to disrupt exclusionary practices that contribute to the incapacitation of citizenship’ (Reference Edyvane and Kulenović2017, 1360). Shelby uses the criterion of ‘intolerable injustice’ as a justification for law breaking and defines it as the ‘constitutional essentials’ in Rawls' basic framework. Shelby argues that in cases where the basic structure is inegalitarian, and the prevalence of an ideology in society is manifestly unjust, then those who are put in a position of intolerable injustice (in Shelby's case, America's ‘ghetto poor’) have no obligation to abide by the law (Reference Shelby2007, 145). The criterion that determines if breaking anti-riot law is justified is whether or not the riot is protesting a fundamentally unjust state action or law. Just as other forms of justified law breaking recognize a right to resist unjust laws, a riot would be justified if it is protesting an unjust law. The easiest way to determine whether the law in question is unjust is to assess whether it contradicts a more fundamental principle of constitutional law, or the basic law of a society.

Riots can also be made illegal via a public declaration or judgment of the police. While crowds may gather to protest a grievance, it is only when the authorities declare the protest a riot that the crime of rioting occurs. Legally, this post facto constitution through labelling is most explicit in the idea of ‘reading the riot act’. This expression is based on Britain's Riot Act of 1714, which empowered local officials to read out a proclamation that ordered any group of twelve or more individuals who were publicly assembled and behaving riotously to disperse within an hour. If any participants failed to disperse, they were guilty of a riot. The British Crown thus invented the concept of rioting as a crime in order to set limits on protest and dissent. The state, through its officers, decides what protests count as a riot; in making this decision, a protest turns into a riot.

Authorities can use both unlawful assembly and riot dispersal orders to control and stop the expression of dissent. Sometimes authorities issue dispersal orders knowing that they will not hold up in court simply as a means of preventing or ending a protest (Inazu Reference Inazu2017, 34). Anti-rioting laws are partially about controlling the basic freedoms of public assembly and speech. Sometimes these rules are either overapplied or applied in bad faith. This points to a second criterion of justified law breaking with respect to riots – are the authorities using riot law to disperse a lawful and peaceful assembly? A very high threshold is needed for authorities to invoke disturbing the peace laws to end a protest. Public safety should only be invoked to disperse a protest when the crowd directly threatens the safety of public bystanders who are not participating in the protest.

How is a Riot Extra-Parliamentary?

Democratic theory assumes that there are procedures that individuals can use to shape laws and public policies, as well as express their dissent. The normal mechanisms of democracy are voting, petitioning one's representatives in government, the free expression of ideas through mass media outlets, public demonstration and protest. When a riot expresses a grievance, it operates outside these normal parliamentary processes in two ways. First, it abandons the normal means of petitioning the government. These mechanisms are premised on the idea that a portion of the citizenry can use persuasion to bring about policy change. Persuasion consists of spoken and written words used to change a person's beliefs through a combination of reasons, rhetoric and emotion. Conversely, a riot is expressive and a form of resisting the government's authority through uncivil disobedience. Expression is concerned solely with making one's own thoughts public; it does not involve using reason to change the beliefs of others. Riots express noncompliant rage. If this rage is justified, then the riot may prompt the authorities and the public to confront the underlying injustice that the rioters are contesting. Fear, rather than reason, is a crucial component of riots.Footnote 23 Rioters use fear to intimidate bystanders, targets and the authorities in the hopes that it will compel policy change.Footnote 24 The riot is also a mode of resistance rather than a form of persuasion. It entails acting in such a way so as ‘not to be governed like that’ (Foucault Reference Foucault2007, 44). Whereas parliamentary practice assumes that groups will try to use the force of the better argument to petition a group to change its policy, riots seek to provoke change through expressive rage and militant disobedience.

Secondly, a riot is extra-parliamentary in the sense that the rioting crowd is not an organized group that fits within the normal political process. While a group may call a demonstration that breaks out into a riot (such as the Poll Tax Riot in London in March 1990), or in some instances (such as the Black BlocFootnote 25 protests at the Hamburg G20 riots in July 2017) a group might actively instigate a riot, the rioting crowd does not operate in a way that is normally recognized by parliamentary processes. This is because it cannot take the form of an institution or practice that a legislature and its officials can formally recognize. It is not a political party or social movement or special interest group; it is a spontaneous organization – spontaneous not in the sense of being unplanned, but in the sense of being sui generis and temporary.Footnote 26 A group might instigate or organize a riot, or even use a riot as a political tactic, but the riot is a distinct and discrete event. Riots, like a temper tantrum or thunderstorm, are intense but fleeting.Footnote 27 They are not institutions; nor are they institutionalizable in the sense of ‘an arrangement for maintaining order, resolving disputes, selecting authoritative leaders, and thus promoting community between two or more social forces’ (Huntington Reference Huntington1968, 9). A riot does none of these things, and is not a stable or recurring pattern of social behaviour. Each riot is a unique occurrence.

Riots that enable those within the community whose grievances are either not voiced within normal parliamentary procedures or are systematically ignored through normal political mechanisms are permissible. D'Arcy argues that militant political action, such as rioting, is appropriate when it conforms to what he calls the democratic standard. The democratic standard rests on two principles. First, democracy is ‘the self-governance of the people through inclusive, reason guided public discussion’ (Reference D'Arcy2014, 4). Secondly, there are circumstances in which ‘it is consistent with the democratic ideal to set aside discussion and apply forceful pressure through adversarial, confrontational protest’ (Reference D'Arcy2014, 5). D'Arcy argues that if a community lacks an effective mechanism for expressing its grievances, then a riot is ‘a kind of exit: a temporary withdrawal from attributing authority to the legal order’ (Reference D'Arcy2014, 154).Footnote 28 In most instances of grievance rioting, the participants lack the ability to exercise their voice; institutions often silence these communities through their structures. We can think here of Ferguson, Missouri and the massive under-representation of African Americans in both the Ferguson Police Department and the City Council as an example of a polity failing to provide voice in a systematic way for an extended period of time.Footnote 29 Contra the claim made by many liberal critics of riots, grievance riots do work: they provoke a response from the authorities. In high-profile and large-scale riots, the public authorities normally respond by appointing a commission of inquiry that investigates the causes of the riot and proposes recommendations (D'Arcy Reference D'Arcy2014, 155). While rioting to demand an official inquiry to create policy change is not the most desirable (or even efficient) means of giving voice to the voiceless, when a political order systematically blocks all other means of airing and receiving redress for a grievance, then a riot is justified. The criterion by which one may justify a riot's extra-parliamentarianism is whether or not the parliament has systematically ignored or blocked a group from receiving redress for their grievance through normal parliamentary procedures. Riots usually target local problems and specific grievances.Footnote 30 Politically motivated riots express a distinct grievance that is normally dealt with through parliamentary procedures. But if the parliamentary system either ignores or blocks the grievance, the riot is an extra-parliamentary act of last resort.

Conclusion

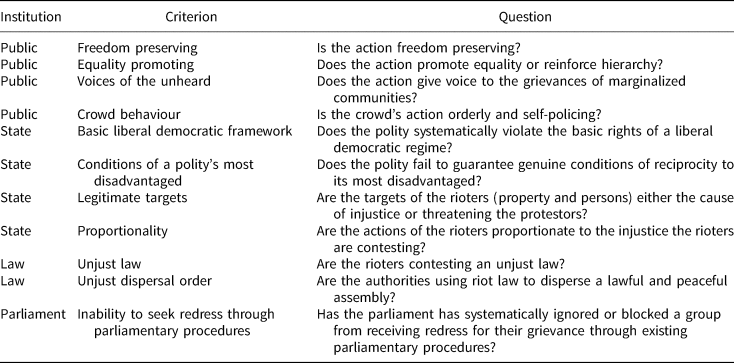

Political theorists do not consider riots as a legitimate form of political resistance because they operate outside four of the main institutions that most Western political theorists defend. Considering these four forms of extra-institutionalism together – the fact that riots are extra-public, extra-state, extra-legal and extra-parliamentary – generates two conclusions. First, because there are widely accepted justified exceptions to these institutions in other areas of political theory, these reasons can also apply to riots. Secondly, because a riot is extra-institutional in four ways it needs to meet the criteria of a justified exception in each of these four institutions in order to be justifiable. This makes the threshold for justifying a riot potentially higher than other forms of political resistance, but this higher threshold does not mean that no riots are justifiable. I have identified eleven criteria that can be used to assess the legitimacy of a riot (Table 1).

Table 1. Just riot criteria

These criteria are not intended to provide a simple check box exercise for assessing a riot. They should instead be used to reflect on the features of individual riots, on a case-by-case basis. Political theorists can use the criteria to determine whether an individual riot is justified or unjustified. At a minimum, in order for a riot to be justifiable it must offer legitimate reasons for disobeying each of the four institutions that are on par with the recognized forms of legitimate extra-institutionality in other practices of resistance. The more criteria a riot satisfies, the more confident we can be that it was justified.

Why would we need to make such a set of judgments? In the case of just war theory (at least in the ideal case), the argument about a war's justifiability should take place prior to its outset. Such a deliberation is unlikely in the case of riots. A just riot theory would instead provide a means of assessing the validity of a particular riot after the fact, which would allow us to determine the appropriate response to it. At a minimum, we need such a theory to distinguish between riots after a sports team wins and those protesting police murders of unarmed citizens. Treating all riots a priori as illegitimate unfairly dismisses the grievances of the unheard, and potentially denies some of the most marginalized members of society the ability to voice their concerns. Conversely, developing a vocabulary and theory of just riots would allow us to make judgments about whether particular riots were justified, how the authorities should respond to the rioters' grievances, and how individual rioters should be punished (or excused) for their actions. It is time for political theorists to stop ignoring the fact that riots constitute a form of politics and develop a just riot theory.

Acknowledgements

I thank the following people for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article: Ann Towns, Helen Kinsell, Giunia Gatta, Ilan Baron, Dan Nexon, Dan Green, Enes Kulenović, Kerri Wood, Patricia Springborg, Martin Breaugh, Douglas Dow, Patchen Markell, Amentahru Wahlrab, David Owen, Chris Armstrong, Christian Volk, Friederike Kuntz, Duncan Bell and Rob Jubb. Earlier versions of this article were presented at the 2016 meeting of the ECPR, the 2017 meeting of the WPSA, the University of Gothenberg, the University of Zagreb, Cambridge University and the Free University of Berlin.