Ebstein’s anomaly diagnosed in fetal life is associated with high perinatal mortality.Reference McElhinney, Salvin and Colan1,Reference Barre, Durand and Hazelzet2 A recent multicenter study showed that the risk of fetal demise or neonatal death was approximately 45%.Reference Freud, Escobar-Diaz and Kalish3 Pulmonary insufficiency with circular shunt was the most important predictive risk factor for perinatal mortality. The circular shunt is prompted by the combination of pulmonary insufficiency and tricuspid regurgitation, causing continuous retrograde ductal flow and intracardiac recirculation, which results in low tissue perfusion and a life-threatening condition.Reference Elzein, Subramanian and Ilbawi4 Therefore, effective treatment of fetuses and neonates with Ebstein’s anomaly with a circular shunt is an urgent task that should start soon after the fetal diagnosis.

This study aims to describe our successful transplacental treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in a 29-week gestation fetus followed by an innovative surgical approach consisting of a Starnes procedure immediately after birth and biventricular repair using Da Silva’s cone repair at 5 months.

Case report

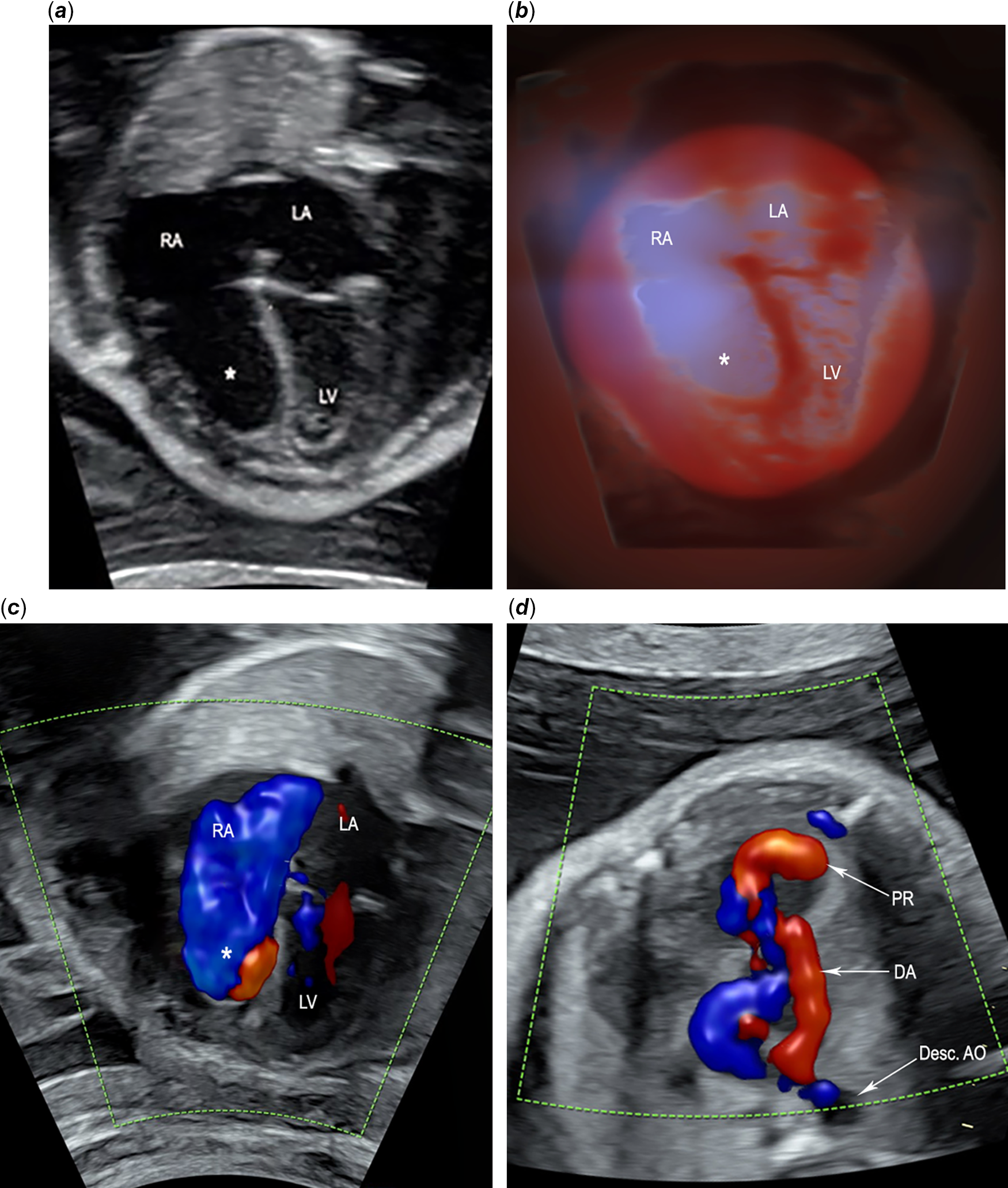

A 29-week gestation fetus was diagnosed with severe Ebstein’s anomaly and circular shunt by fetal echocardiogram. The displacement of the septal, inferior, and part of the anterior leaflets caused massive tricuspid regurgitation (Fig 1a–c) (Supplementary videos S1–S2). The tricuspid valve was extremely rotated into the right ventricle outflow tract resulting in a small functional right ventricle. The atrialised RV and right atrium had severe dilation, causing ventricular septal paradoxical movement. Severe pulmonary insufficiency and an enlarged and unrestrictive ductus arteriosus were associated with continuous pattern torrential flow on Doppler (Fig 1d) (Supplementary video S3). The cardiothoracic area ratio was 0.42, and there was no fetal hydrops. Considering the risk of fetal demise, we initiated NSAIDs transplacental treatment to promote ductal constriction by giving dipyrone 3 g/day, orally to the mother. However, cardiomegaly progressed (CTAR = 0.50), and we noted mild ascites and pleural effusion after 6 days. At 30 weeks, indomethacin was started at 100 mg/day with a lower dipyrone dose (2 g/day), resulting in ductal constriction and reduced heart size (CTAR = 0.39), and resolution of ascites and pleural effusion. Two weeks later, cardiomegaly worsened again, and we replaced dipyrone with 300 mg/day of ibuprofen and a higher dose of indomethacin (300 mg/day), which accentuated the ductal constriction (Fig 2 a, b) (Supplementary video S4). On the 34th gestational week, a C-section was indicated due to oligohydramnios. Based on the fetal echocardiography findings, which indicated a high risk of early neonatal death, we planned immediate surgical intervention in a side-by-side operating room. A 2110 g female with Apgar scores of 9/9 was delivered, presenting with rapid deterioration and acidosis. A postnatal echocardiogram confirmed EA with a massive circular shunt. A marked paradoxical movement of the ventricular septum was impinging the left ventricle, resulting in an LV ejection fraction of 16% (Simpson method). We performed an urgent Starnes procedure, consisting of RV exclusion using a fenestrated patch over the tricuspid valve annulus, patch occlusion of the proximal main pulmonary artery, and placement of a 3.5 PTFE shunt from the innominate artery to the distal main pulmonary artery. After the procedure, the patient’s haemodynamics improved dramatically by interrupting the circular shunt and the ventricular septum paradoxical movement (Fig 2c). The patient was discharged from the hospital on the 56th post-operative day, weighing 2645 kg. Thereafter, her cyanosis gradually increased, and serial 3D echocardiograms showed progressive RV involution. At 4 months old, she presented with low 3D RV indexed diastolic volume (15.3 ml/m2) and ejection fraction (7%), but normal RV free wall longitudinal strain of −23.3% (normal = −18.7% ± 6.6)Reference Houard, Benaets and de Ravenstein5 (Supplementary Table S5). At 5 months old, we proceeded with the Starnes takedown and performed a two-ventricle repair using the Da Silva cone technique, fenestrated patch closure of atrial septal defect, and intraoperative assessment on the need for adjunctive Glenn procedure. Off cardiopulmonary bypass, her oxygen saturation was 92%, averting the Glenn procedure. In the ICU, she had presented with moderate RV dysfunction and oxygen saturation levels in the range of 78%–87%, requiring inotropic support with low dose epinephrin and milrinone. Afterwards, she had gradual clinical and echocardiographic improvement (Fig 2d). On the 20th post-operative day, her 3D echocardiogram showed progressive recovery of the RV indexed diastolic volume (from 15.3 ml/m2 to 31.0 ml/m2) and the ejection fraction went from 7% to 55%, though the RV function based on its free wall longitudinal strain was mildly decreased (−12%). Currently, 8 months after the cone repair, she is asymptomatic, thriving well, and presenting with oxygen saturation of around 94%.

Figure 1. Fetal echocardiogram at 29-week gestation of Ebstein’s anomaly with a large circular shunt. (a) End-systolic phase shows near-complete atrialisation of the right atrium caused by the severe displacement of the tricuspid septal and posterior leaflets into the inlet portion of the right ventricle (asterisk). No tricuspid valve leaflets are seen in this view. (b) Tridimensional reconstruction of the four-chamber view using spatiotemporal image correlation with render mode HD live silhouette, which produces a shadowing effect that clearly delineates the enlarged right atrium with the atrialised inlet portion of the right ventricle (asterisk). (c) End-systolic phase shows significant tricuspid regurgitation, which reaches the posterior wall of the RA, filling it completely (blue). Atrialised inlet portion of the right ventricle (asterisk). (d) Colour flow imaging of the circular shunt shows a large retrograde jet (red) from the aorta to the pulmonary artery through a large patent ductus arteriosus, then to the right ventricle, where we can see the pulmonary regurgitation jet. Desc AO=descending aorta; DA=ductus arteriosus; LA=left atrium; LV=left ventricle; PR=pulmonary regurgitation; RA=right atrium; RV=right ventricle.

Figure 2. Fetal and transthoracic postnatal echocardiography studies depict the results of fetal and postnatal medical and surgical therapies. (a) Initial fetal echocardiogram done on the 29-week gestation shows the enlarged ductus arteriosus during systole (in red), and the correspondent Doppler tracing of the ductus arteriosus displays low velocities (peak systolic, 1.36 m/s; diastolic, 0.35 m/s) and a pulsatility index of 1.74. (b) Fetal colour Doppler image obtained on the 34-week gestation after 5 weeks of fetal treatment with dipyrone, indomethacin, and ibuprofen shows that the ductus arteriosus is narrow and tortuous during systole (the colour Doppler is inverted to be comparable with Fig 2a). The correspondent Doppler tracing on the 34-week gestation confirms the ductus constriction with significantly increased flow velocities (peak systolic, 2.27 m/s; diastolic, 1.14 m/s) and a lower pulsatility index of 0.75. (c) Transthoracic echocardiogram at 3 months after the modified Starnes procedure shows fenestrated patch over the tricuspid valve with diastolic flow, ventricular septum deviated to the right, and globular shaped left ventricle with normal function. (d) Transthoracic echocardiogram at 20 days after the two-ventricle repair shows a good size right ventricle, the tricuspid valve positioned at the normal atrioventricular junction opens well in diastole. Desc AO=descending aorta; DA=ductus arteriosus; FP=fenestrated patch; LA=left atrium; LV=left ventricle; S=ventricular septum.

Discussion

EA with a large circular shunt often evolves with RV volume overload and low cardiac output, causing fetal demise, premature birth, or resulting in an extremely ill neonate. Intrauterine therapy with NSAIDs is a viable strategy for fetal survival by promoting ductal constriction and decreased ductal shunting, as reported recently.Reference Torigoe, Mawad and Seed6 In our case, the decision to initiate fetal treatment with dipyrone, a pyrazolone derivative and a mild inhibitor of prostaglandin synthetase, was based on the author’s personal experience diagnosing several fetuses with ductal constriction related to maternal chronic use of this drug.Reference Lopes, Carrilho and Francisco7 Here, the fetal response was transient, and its replacement by ibuprofen and indomethacin was, ultimately, required to maintain ductal constriction until birth at 34 weeks gestation.

The fetal echocardiography demonstrating the severe EA with circular shunt incited the prompt neonatal surgical intervention, avoiding clinical deterioration. The RV exclusion with the Starnes procedure allowed the LV to acquire better volume loading and performance by ceasing the ventricular septal paradoxical movement.Reference Reemtsen and Starnes8

Neonates with EA palliated with the Starnes procedure usually follow a single-ventricle repair pathway.Reference Elzein, Subramanian and Ilbawi4 However, it was already demonstrated that RV rehabilitation after the Starnes is possible in patients with EA and pulmonary atresia.Reference Knot-Craig, Overholt and Ward9,Reference Da Silva, Viegas and Castro-Medina10 This biventricular conversion avoids the potential long-term complications of Fontan circulation.

The low RV ejection fraction after the Starnes procedure seen in our patient could discourage the biventricular repair. Nevertheless, our patient presented with an excellent ejection fraction within 3 weeks after the cone reconstruction, as estimated by 3D echocardiography. This fact suggests that interpreting low ejection fraction as myocardial impairment can be misleading after the Starnes procedure given the underfilled load condition of the right ventricle. In contrast, the deformation measured by the RV free wall longitudinal strain was normal (−23.3%), which is consistent with our patient’s favourable outcome after the biventricular repair, confirming its prognostic value.Reference Houard, Benaets and de Ravenstein5

In conclusion, early fetal diagnosis, and ductal constriction treatment in EA with circular shunt was crucial to improving fetal survival and development, allowing the neonatal Starnes procedure and subsequent successful biventricular repair using the Da Silva cone operation.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951121000081.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. Carlos Cateb for his computer assistance in preparing the figures.

Financial support

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work have ethical approval from the Institutional Research Board of the Beneficencia Portuguesa Hospital in Sao Paulo, under the number 4.203.795. The patient’s parents were counselled about the risks and benefits of the medical procedures and signed consents for the procedures and for publication of the medical data.