In the wake of the 2019 constitutional crisis, civil unrest, and the nationwide referendum held a year later, Chile has faced several issues regarding citizens’ rights. Acceptance of homosexuality is one such topic. According to data from the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP Research Group 2000, 2020), over the past three decades Chile has experienced a sizable increase in people’s acceptance of homosexual relationships, from barely 6.0% in 1998 to almost 40% in 2018. Chile has since followed the path of other high-income countries in Latin America, such as Argentina and Uruguay (Corrales Reference Corrales2017), and has promoted intense reforms to expand rights for gay and lesbian individuals (Slenders, Sieben, and Verbakel Reference Slenders, Sieben and Ellen Verbakel2014). At a purely legal level, Chile has passed laws in favor of same-sex relationships designed to foster nondiscrimination, has just legalized homosexual marriage and adoption, and is currently in the process of reforming the Criminal Code to equalize the age of consent for same-sex couples. In addition, the final draft of the new Chilean Constitution, rejected in September 2022, included the prohibition of any kind of discrimination based on sexual orientation in its article 25.4.

Apart from the timeliness of the topic in Chile, with many studies on the determinants of attitudes toward homosexuality—which include several focused on Latin America and the Caribbean (Lodola and Corral Reference Lodola and Corral2010; Chaux and León Reference Chaux and León2016; Navarro et al. Reference Navarro, Barrientos, Gómez and Bahamondes2019; Seligson, Moreno-Morales, and Russo Reference Seligson, Moreno Morales and Russo2019)—very few studies have explored the drivers of changing views on this issue over time, and those that exist are limited to the United States and Canada (Loftus Reference Loftus2001; Andersen and Fetner Reference Andersen and Fetner2008b; Lewis and Gossett Reference Lewis and Gossett2008; Pampel Reference Pampel2016; Lee and Mutz Reference Lee and Mutz2019). Furthermore, concrete evidence for Chile comes from the field of psychology and involves small samples of university students (Cárdenas et al. Reference Cárdenas, Barrientos, Gómez and Frías-Navarro2012; Cárdenas, Barrientos, and Gómez Reference Cárdenas, Barrientos and Gómez2018) at a specific moment in time, whereas our study uses several waves of a nationally representative survey of attitudes that covers two decades of attitudes. Finally, the availability of twenty years of comparable good-quality data from the ISSP also makes the case for researchers to study the Chilean case.

Compared to prior studies, this research strengthens the evidence on the long-term trend in the acceptance of homosexuality in a very different institutional and cultural framework, namely, Chile. This country has witnessed an impressive shift in these attitudes that is comparable to changes observed much earlier in the most advanced developed countries (see, among many others, Kuyper, Ledema, and Keuzenkamp Reference Kuyper, Ledema and Keuzenkamp2013; Smith, Son, and Kim Reference Smith, Son and Kim2014; Roberts Reference Roberts2019). In particular, this article explores the evolution of the acceptance of homosexuality in Chile between 1998 and 2018 and investigates the role played by several individual features identified as key variables in the literature (gender, location, birth cohort, age, level of education, religiosity, political orientation, and social capital). Using the 1998 and 2018 waves of the ISSP (ISSP Research Group 2000, 2020), we perform an econometric decomposition that allows disentangling the relevance of changes in individual socioeconomic variables and the importance of the evolution of attitudes due to each characteristic. Our results suggest that changes in observed individual-level socioeconomic characteristics explain roughly 11.0 percent of the shift in attitudes. Particularly, the increase in educational attainment and generational replacement account for around 8.0 percent of the broader acceptance of homosexuality. This roughly constitutes a 45.0 percent increase in magnitude over the initial level. Nevertheless, most of the decrease in the rejection of homosexual relationships in Chile responds either to compositional changes in demographics or to shifts in attitudes that are attributable to sociodemographic characteristics. We argue that these findings are consistent with Inglehart’s postmaterialist theory (Inglehart and Flanagan Reference Inglehart and Flanagan1987; Inglehart Reference Inglehart1990; Inglehart and Baker Reference Inglehart and Baker2000) and with world society theory (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Boli, Thomas and Ramírez1997; Symons and Altman Reference Symons and Altman2015). Drawing on prior literature, we discuss potential aggregate country-level factors and unobservable variables that might have informed these outcomes. The second contribution of our research is thus of a methodological nature: we propose an econometric decomposition that is widely used in labor market studies to separate composition effects from structural changes, thus overcoming certain issues encountered in previous studies.

Context and theoretical framework

Attitudes toward homosexuality in Latin America and Chile

There is abundant research on the increased acceptance of homosexuality all over the world since the end of World War II. People have become more open minded and respectful of diversity, including homosexual relationships (Gibson Reference Gibson1992; Zhang and Brym Reference Zhang and Brym2019). Nonetheless, according to Roberts (Reference Roberts2019, 42), this shift has not been homogeneous.

Regarding trends over time, there is evidence of a broad global upswing in the acceptance of homosexuality between 1981 and 2012. Change has not only occurred in Western countries. Generally speaking, global attitudes toward homosexuality also became more positive over this time, albeit varying considerably from one country to another.

Although a global analysis shows a general decrease in homophobic attitudes, a closer look at the evidence reveals that this reduction has been more intense in Western societies, and numerous countries elsewhere continue recording high levels of intolerance toward homosexual relationships (Jäckle and Wenzelburger Reference Jäckle and Wenzelburger2015, 208). In this sense, a 2019 Pew Research Center survey shows that between 2002 and 2019 there was a general worldwide increase in the acceptance of homosexuality, especially in South Africa, India, Turkey, and Japan. However, this research also revealed that some countries have not recorded any statistically significant progress (Poushter and Kent Reference Poushter and Kent2020, 25).

Latin America has historically been a hostile environment for individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer, asexual, or otherwise through several discriminating attitudes, including violence (e.g., murder, aggression, sexual abuse) and social and labor market exclusion (Encarnación Reference Encarnación2011).

Over the past decades, though, most countries in Latin America have enacted far-reaching legislative reforms designed to foster acceptance of homosexuality and, in particular, to decriminalize same-sex relationships. Remarkable progress has been made in the region in terms of the acceptance of same-sex relationships (Roberts Reference Roberts2019), albeit with widely differing levels, with major differences between countries such as Argentina and Uruguay and others such as Guatemala and Nicaragua (Lodola and Corral Reference Lodola and Corral2010). According to the Latinobarometer (Corporación Latinobarómetro 1998, 2009), the percentage of people who would not like to have LGBTQIA+-identifying individuals as neighbors fell from 51 percent to 29 percent in Latin America between 1998 and 2009. Chile recorded a similar trend, with a decrease from 44 percent to 23 percent over the same period. Footnote 1

Chile’s attitude toward homosexuality was highly influenced by the Pinochet dictatorship, which promoted conservative values and condemned any kind of nontraditional sexuality (Carvajal Reference Carvajal2019). This hostility continued even after the restoration of democracy in 1990, thus leading to a relative delay—compared to other Latin American countries with higher levels of human development—in the implementation of policies recognizing sexual rights. For example, in 1999 Chile was the penultimate country in Latin America to decriminalize same-sex relationships. Thirteen years later, in 2012, following the murder of a gay teen, Daniel Zamudio, by a neo-Nazi group, Chile passed an antidiscrimination law that included protections for the LGBTIQA+ community. Nonetheless, this approval required seven years of debates in the Chilean congress and faced strong opposition from conservative civil and religious organizations (Díez Reference Díez2015). The Civil Union Bill (Acuerdo de Unión Civil), which includes same-sex relationships, was not passed until 2015. A year later, article 2 of the 2016 Modernization of Labor Relations Act No. 20,940 reformed the Chilean Labor Code, explicitly forbidding any kind of employment discrimination because of sexual orientation (Mendos Reference Mendos2019).

In 2016, Chile was one of the Organisation for the Co-operation and Economic Development (OECD) countries with a worst record in terms of recognition of LGTBIQA+ rights. By then, Chile scored only six out ten points in the OECD’s list of items for assessing the legal recognition of homosexual orientation (Valfort Reference Valfort2017). However, in the past years, Chile has experienced a remarkable evolution toward the recognition of homosexual rights. It legalized same-sex marriage and adoption in December 2021 (a reform that came into force in March 2022). Footnote 2 Moreover, the draft of the constitution rejected in the plebiscite in September 2022 aimed to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation (already forbidden by the criminal law). Even though age limits are still different for heterosexual and homosexual acts (fourteen and eighteen years old, respectively), a proposal to reform the Criminal Code is currently under discussion. Footnote 3

All in all, since 1990 Chileans have experienced a constant increase in the acceptance of sexual diversity according to different data sources (Barrientos Reference Barrientos2015). The reasons for the general time lag in all these changes—compared to Argentina or Uruguay, for example—are still being debated (Contardo Reference Contardo2011; Díez Reference Díez2015; Corrales Reference Corrales2017). Schulenberg (Reference Schulenberg2019, 13–14) has pointed to the fragmentation and weakness of the LGBTQIA+ movement, historically divided into various factions, including the Movimiento de Integración y Liberación Homosexual (Movement for Homosexual Integration and Liberation), which has split internally into the Movimiento Unificado de Minorías Sexuales (Unified Movement of Sexual Minorities) and Fundación Iguales (Equals Foundation).

Theoretical framework and literature review

There is a large corpus of literature that seeks to identify variables that may shape attitudes toward homosexuality. This research also suggests the importance of both demographic characteristics and country-level factors.

There are numerous socioeconomic drivers that can potentially explain the formation of attitudes toward homosexual relationships. First, males are often less accepting of homosexuality than women (I-Huston and Waite Reference I-Huston and Waite1999). In this respect, several studies have posited that men have stricter expectations of masculinity, so tend to reject homosexual males more (Kite and Whitley Reference Kite and Bernard1996; Louderback and Whitley Reference Louderback and Bernard1997).

This literature also identifies the relevant role of location of residence: it offers consistent evidence that residents in rural areas are less accepting of homosexual relationships than the urban population is. Some researchers have emphasized the importance of community size: while those individuals living with people similar to themselves (“provincials”) tend to develop individual or communitarian attitudes, those living in larger urban locations (“cosmopolitans”) are more likely to be in contact with a more heterogeneous community, thus developing a more open-minded attitude (Andersen and Yaish Reference Andersen and Yaish2003; Andersen and Fetner Reference Andersen and Fetner2008a).

Complementarily, birth cohort is a potential factor for analyzing acceptance of same-sex relations. In this sense, exposure to certain social, historical, and cultural events can have an impact on the development of individual attitudes. Therefore, the sociocultural environment surrounding individuals can consolidate social generations joined by particular views or perceptions (Haavio-Mannila, Roos, and Kontula Reference Haavio-Mannila, Roos and Kontula1996, 410). In this sense, more recent birth cohorts are more likely to show more tolerant attitudes toward sexual diversity, including same-sex relations (Treas Reference Treas2002; Andersen and Fetner Reference Andersen and Fetner2008a; Lewis and Gossett Reference Lewis and Gossett2008; Kranjac and Wagmiller Reference Kranjac and Wagmiller2021).

According to the existing literature, age is another driver of these kinds of attitudes, as it is often positively related to socially conservative attitudes, including nonacceptance of same-sex relationships. Younger people are usually more accepting of homosexuality than older people (Quillian Reference Quillian1996; Andersen and Fetner Reference Andersen and Fetner2008a; Hooghe and Meeusen Reference Hooghe and Meeusen2013; Navarro et al. Reference Navarro, Barrientos, Gómez and Bahamondes2019; Seligson, Moreno Morales, and Russo Reference Seligson, Moreno Morales and Russo2019). According to Adamczyk and Pitt (Reference Adamczyk and Pitt2009), the relationship between nonacceptance of same-sex relationships and age is especially intense in contexts of political and economic instability.

It is worth mentioning the existence of an ongoing discussion on the modeling of the age cohort and period to understand different generational processes (Bell and Jones Reference Bell and Jones2014). Attitudes like acceptance of homosexuality can be a product of age differences, birth cohort effects, period effects, or a combination of several factors. In this sense, while there are life events that might affect the formation of beliefs about certain topics, there is also a broad consensus that attitudes toward controversial issues stem from generational differences, and there are rarely major discrepancies within each birth cohort (Andersen and Fetner Reference Andersen and Fetner2008a).

The importance of education is also a constant in the studies seeking to understand the main determinants of homophobic beliefs and behaviors. It is generally agreed that higher levels of education are related to higher levels of acceptance of homosexuality (Pampel Reference Pampel2016; La Roi and Mandemakers Reference La Roi and Mandemakers2018), with some researchers attributing this behaviour to the “educational effects explanations,” that is, schooling provides cognitive and reasoning attitudes that involve the assimilation of new views (Campbell and Horowitz Reference Campbell and Horowitz2016). A second branch of literature suggests that liberal values—including acceptance of sexual diversity—are socialized as part of higher education plans (Carvacho et al. Reference Carvacho, Andreas Zick, Roberto González, Kocik and Bertl2013; Slootmaeckers and Lievens Reference Slootmaeckers and Lievens2014). Third, the effect of education might be due to contact with other students and the informal interaction between students and teachers encouraging openness to different views (Pettigrew and Tropp Reference Pettigrew and Tropp2006; Andersen and Fetner Reference Andersen and Fetner2008a). Furthermore, some studies suggest that the role of education is stronger in more developed countries (Seligson, Moreno Morales, and Russo Reference Seligson, Moreno Morales and Russo2019), while its role is limited in authoritarian regimes, which may use education as a means of indoctrination (Zhang and Brym Reference Zhang and Brym2019).

There is compelling evidence to show that higher levels of religiosity in an individual are related to a greater intolerance of homosexuality, both in terms of self-identification (belonging to a religion) and attendance (participating in the religious community) (Rowatt et al. Reference Rowatt, Jo-Ann Tsang, LaMartina, McCullers and McKinley2006; Adamczyk and Pitt Reference Adamczyk and Pitt2009; Adamczyk Reference Adamczyk2017). According to Janssen and Scheepers (Reference Janssen and Scheepers2018, 16), “it seems that every dimension of religiosity has a positive relationship with rejection of homosexuality.” In addition, there is also evidence to show that the intensity of this nonacceptance is highly determined by an individual’s specific religion: while Hinduism, Protestant Evangelicalism, and Islam usually involve higher levels of rejecting homosexual unions, Judaism and Buddhism have higher levels of acceptance (Jäckle and Wenzelburger Reference Jäckle and Wenzelburger2015; Navarro et al. Reference Navarro, Barrientos, Gómez and Bahamondes2019).

Contemporary research also links an individual’s ideological orientation to acceptance of homosexuality. In particular, conservatives tend to record higher levels of rejecting same-sex relationships than liberals (Barth and Parry Reference Barth and Parry2009; Sherkat et al. Reference Sherkat, Powell-Williams, Maddox and Mattias De Vries2011). Jost (Reference Jost2006) links this stance to a reluctance to change and opposition to more egalitarian politics. Van der Toorn and colleagues (Reference van der Toorn, Jost, Packer, Noorbaloochi and Van Bavel2017) suggest that this attitude among conservatives is closely correlated to religiosity and sexual prejudice.

Social capital has also received considerable attention from researchers. According to Putnam (Reference Putnam1995, 35), social capital is understood to be the “features of social organizations, such as networks, norms and trust that facilitate action and cooperation for mutual benefit.” Accordingly, the more social capital a community has, the stronger the ties among its members and the more legitimated its authorities are. Concerning acceptance of homosexuality, authors such as Rohe (Putnam et al. Reference Putnam, Light, Briggs, Rohe, Vidal, Hutchinson, Gress and Woolcock2004) and Walters (Reference Walters2002) highlight the role of civic engagement and social embeddedness in explaining attitudes toward homosexuality. There seems to be a general consensus on how higher levels of social trust and connection to others are related to higher levels of acceptance, including those of homosexual relationships (Lee Reference Lee2014; Jones Reference Jones2015). Nevertheless, despite the overall link between participation in associations and acceptance, belonging to certain specific groups—such as veterans’ associations or church congregations—might have a negative impact on attitudes toward homosexuality. Specifically, this research adopts a twin approach to measure social capital. On the one hand, we analyze trust in people, which Putnam (Reference Putnam1995, 230) has signaled as crucial for understanding social connectedness and civic engagement; on the other hand, we use trust in institutions as an intermediate variable that reflects the overall level of social capital. These two variables are used to integrate both the informal and formal aspects of social capital, respectively (Nooteboom Reference Nooteboom2007).

The results of the specific research on Latin American and Caribbean countries are consistent with the findings of international literature, highlighting the role of gender, religion, education, ideology, location of residence, economic and social development, and education as the main predictors of acceptance of homosexuality (Lodola and Corral Reference Lodola and Corral2010; Chaux and León Reference Chaux and León2016; Navarro et al. Reference Navarro, Barrientos, Gómez and Bahamondes2019; Seligson, Moreno Morales, and Ruso Reference Seligson, Moreno Morales and Russo2019). There is also some literature focusing solely on the Chilean case, such as studies by Cárdenas and colleagues (Reference Cárdenas, Barrientos, Gómez and Frías-Navarro2012) and Cárdenas, Barrientos, and Gómez (Reference Cárdenas, Barrientos and Gómez2018). By analyzing relatively small samples of university students (fewer than three hundred individuals), these authors highlight the role of gender, religiosity, gender role beliefs, and authoritarian attitudes in line with the findings mentioned here.

Data and methods

Data

This study uses the second and fourth waves of the ISSP Religion Module for Chile conducted in 1998 and 2018 (ISSP Research Group 2000, 2020). These cross-sectional surveys in Chile are administered by the Center of Public Studies, a private nonpartisan and nonprofit academic foundation of renowned experience and reputation in such studies. This institution uses a three-stage sampling and region-level stratified design. This module collects information on religious attitudes and beliefs together with a relatively rich set of socioeconomic characteristics of the Chilean population eighteen years of age or older. The initial sample sizes of the 1998 and 2018 waves are 1,500 and 1,400 observations, respectively. Footnote 4

The key feature of this survey is that it captures attitudes toward homosexuality in a homogeneous way through the following question: “Do you think it is wrong or not wrong if two adults of the same sex have sexual relations?” The possible answers include “always wrong,” “almost always wrong,” “wrong only sometimes,” “not wrong at all,” and “can’t choose, don’t know.” To make the econometric analysis more tractable, we recode the variable into two categories: same-sex relationships are not wrong at all according to the respondent and other possibilities. Our derived variable takes the value of 1 if the individual does not consider this type of relation to be wrong and 0 otherwise.

Furthermore, based on the previous literature on attitudes toward homosexuality, we consider the following potential explanatory variables of interest: gender, location of residence (rural or urban), birth cohort, educational attainment, religiosity, political affiliation, trust in other people, and trust in institutions (as the two dimensions of social capital). As mentioned earlier, the role of age in shaping acceptance of homosexuality is not totally clear (Andersen and Fetner Reference Andersen and Fetner2008a). Its role might be just a result of birth cohort effects, period effects, or a combination of the two. The methodology used here, outlined below, requires the inclusion of period effects. Our baseline estimation considers cohort effects, and we present the results including age effects in the supplementary online material (Tables S2 and S3).

Given that the sample sizes are moderate, we recode some variables to avoid multicollinearity issues. First, we consider individuals to be religious if they declare themselves to be (irrespective of the strength of this commitment). Second, we look at political affiliation as a proxy for ideology, which is not available in this survey, considering the following four categories: left (voter of any of the parties that makes up the Concertación, or the New Majority, apart from the Christian Democratic Party, and other more leftist political groups), center, right (the National Renewal Party and the Independent Democratic Union), and last, any other affiliation (all other possibilities, including abstention or blank voting). Third, following the discussion in the previous section, we consider two measures of social capital. The first uses the respondent’s degree of trust in people, a binary variable computed from a question with four possible levels of trust. This variable is recoded as 1 if the individual considers that people can always or usually be trusted and as 0 otherwise. The second one draws on a battery of questions on trust in different national institutions (parliament, church and religious organizations, courts and the legal system, and school and the education system). We create a binary variable with a value of 0 or 1 for each institution covered by these questions (based on whether the respondent expressed trust in them). The answers to the four questions are summed to calculate an index of confidence in institutions ranging from 0 (no confidence in any of the institutions) to 4 (confidence in all four institutions covered).

The rationale for the inclusion of the variables as covariates comes from the findings highlighted in prior literature. First, women tend to be more positive toward homosexuality than men. Second, the view of people living in urban areas usually evidences higher levels of acceptance of homosexual relationships than their rural counterparts. Third, these attitudes are expected to become more negative with age. Fourth, education should have a positive effect on the acceptance of homosexuality. Fifth, conversely, the prior literature suggests that religiosity might have a detrimental impact in this matter. Sixth, according to previous evidence, we expect right-wing individuals to be less prone to agree with homosexual relationships. Seventh, the higher the level of social capital, the more positive is the expected attitude toward homosexuality.

Methods

The main descriptive statistics are presented for the evolution of attitudes toward homosexual relationships in Chile between 1998 and 2018. Our main task consists in identifying the factors that drive the changes in the acceptance of homosexuality among the Chilean population over time. An econometric decomposition is performed to disentangle those changes due to individual socioeconomic characteristics and those attributed to structural changes related to how the views of people with certain demographic features evolve over time.

Our approach consists of applying a version of the well-known Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition (Blinder Reference Blinder1973; Oaxaca Reference Oaxaca1973) adapted to binary variables, closely following the procedure proposed by Gomulka and Stern (Reference Gomulka and Stern1990) and Yun (Reference Yun2004) (for some applications of this decomposition, see Gang, Sen, and Yun Reference Gang, Sen and Yun2008; Muñoz de Bustillo and Antón Reference Muñoz de Bustillo and Antón2010; Antón, Muñoz de Bustillo, and Fernández Macías Reference Antón, Muñoz de Bustillo and Fernández-Macías2014).

Specifically, the method unfolds as follows. First, we separately estimate logit models for 1998 and 2008 to explore the determinants of the acceptance of homosexuality in those years. We record the changes over time according to the variation due to the differences in characteristics by adding and subtracting the predicted probability of accepting homosexuality if the population in 1998 determined their attitudes as individuals interviewed in 2018. This means separating the twenty-year difference in a component due to the change in characteristics, and therefore capturing the differences existing if the population in 1998 behaved as respondents in 2018, and the discrepancy associated with structural changes in the responses (i.e., the differences related to the changes in the coefficients, obtained by applying the coefficients of both years to the population in 2018). The covariates included in the analysis are those discussed in the previous section. The explained and unexplained parts corresponding to each variable are computed by following the solution proposed by Yun (Reference Yun2005, Reference Yun2008). Footnote 5

Results

Our sample’s main descriptive statistics (Table 1) reveal a sea change in levels of acceptance of homosexuality in Chile over time. The percentage of respondents considering that there is no problem at all with same-sex relationships rose from 5 percent in 1998 to 39 percent in 2018. Although there are areas where Chile is still behind its neighbors (e.g., Argentina, Uruguay), the country has actually undergone a remarkable evolution. Regarding the covariates, while the proportion of women remained basically the same, there were changes of different magnitudes in the other variables. From 1998 to 2018, the proportion of people living in an urban area, the demographic weight of younger generations, education levels, and social capital all increased. Both share of religious people and trust in institutions decreased. Finally, reported political affiliation seems to have changed, possibly suggesting a drop in potential left-wing voters, which may well be linked to the 2019 institutional crisis.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

***p < .01. **p < .05. *p < .10.

We then address the determinants of Chileans’ attitudes toward homosexuality by estimating logit models for both years together and separately (Table 2). We present odds ratios, whereby a variable’s positive (negative) effect on the probability of approving same-sex relationships corresponds to an odds ratio greater than (less than) 1. There are several findings. First, sample sizes seem to play a significant role: although the results are fairly similar in terms of statistical significance across models, the standard errors are very large. Second, most of the estimated coefficients agree with our predictions. Gender, location of residence, and trust in institutions have no effect in any of the models; attitudes seem to be more positive among younger birth cohorts and college-educated respondents and, in 2018, among people with high levels of social capital. Finally, Chileans’ views are more negative among religious people and, in 2018, among right-wing voters and people with no political affiliation. Nevertheless, the most salient finding is that, other things being equal, the odds of not having a negative view on same-sex relationships in 2018 are more than eleven times higher than they were in 1998.

Table 2. Determinants of attitudes toward homosexuality in Chile (odds ratios of logit models).

Notes: Heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors between parentheses. The reference category is a male living in a rural area, born between 1956 and 1970, with no formal education, no religious affiliation, with a left-wing affiliation, and no trust in people.

***p < .01. **p < .05. *p < .10.

We explore the drivers of the differences across years through the above-mentioned econometric decomposition. Unfortunately, we cannot directly perform this decomposition using (and interpreting) the results of the models for each year in Table 2. As discussed, we need to estimate normalized regressions to deal with the problem of the omitted group in categorical variables. For the sake of clarity, we do not present the normalized logit regressions underlying the decomposition following the approach proposed by Yun (Reference Yun2004, Reference Yun2005, Reference Yun2008), as they are not directly interpretable.

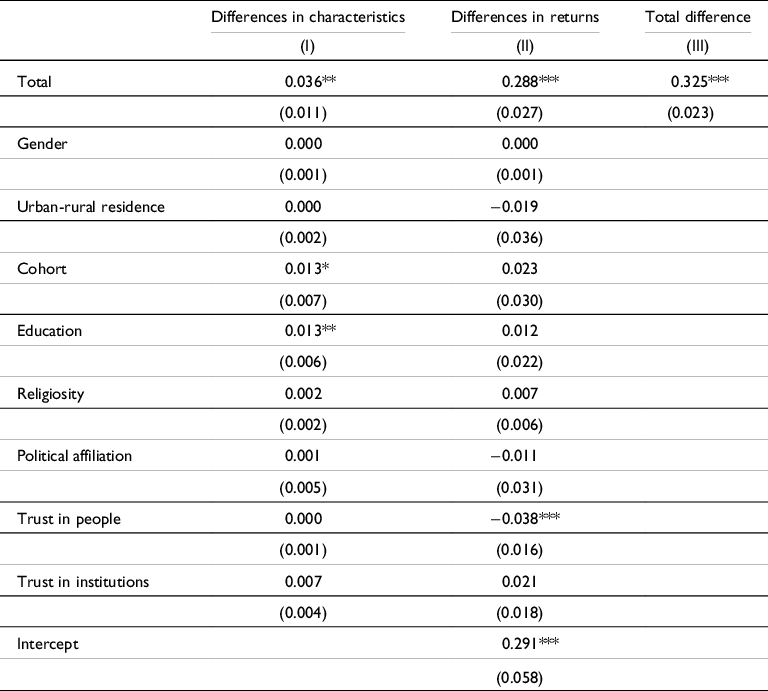

The results of the decomposition (Table 3) are in line with the combined model in Table 2, indicating that 3.6 out of the 32.5 percentage points of change in acceptance of same-sex relationships are due to changes in observable socioeconomic characteristics, whereas structural changes account for 28.8 percentage points. Therefore, the former component accounts for 11.4% of the total improvement in acceptance, and the latter are responsible for the remainder of total change in attitudes.

Table 3. Decomposition of the change in attitudes toward homosexuality in Chile between 1998 and 2018.

Note: Delta method standard errors between parentheses.

***p < .01. **p < .05. *p < .10.

A more detailed look reveals that educational attainment and cohort are the only variables within the former component with a statistically significant effect. Specifically, both increase in schooling and greater weight of new cohorts (i.e., younger generations replacing older ones) raised acceptance by 1.3 percentage points. The changes in the levels of the two variables jointly account for 7.9% of total variation of acceptance over time and represent a 45.2% increase over the level in 1998 (5.4%).

Nevertheless, most of the progress in attitudes toward homosexuality is due to differences in the returns to the observed characteristics. Among the covariates, only trust in others has a statistically significant role. According to our results, if people’s levels of acceptance of homosexuality in 1998 regarding social capital had remained the same in 2018, the attitudes toward this group would have been more positive in 2018 (acceptance would have been more than 3 percentage points higher). Finally, the changes in the intercept account for most of the variation over time (29.1 percentage points). This indicates the relevance of factors we cannot observe or control for in our analysis, either with the levels of those variables other than the observable characteristics included in the model or with changes in their impact on acceptance. We offer a detailed discussion on the potential role of these factors, which we cannot include in the econometric exercise, in the next section.

Discussion

The previous section has shown the results of the analysis of the change in the main socioeconomic determinants of the acceptance of homosexuality among the Chilean population at the individual level. It is worth mentioning that our approach, focused on the view of same-sex relationships, covers only one of the multiple dimensions of the study of attitudes toward homosexuality (Yang Reference Yang1997). As mentioned already, one cannot control for period, cohort, and age effects at the same time. The methodology we use emphasizes period effects. Our main model considers the impact of belonging to a certain generation, but we also estimate it including age effects instead of cohort. These results are presented in the supplementary online material (Tables S2 and S3). They show that age is not relevant for explaining the change in the acceptance of homosexuality in Chile, whereas the rest of the results in the analysis are basically the same. We also assess whether our results hold when replacing an individual’s level of education (a variable with three categories) by years of schooling (a continuous variable), obtaining identical results.

Our results are consistent with prior literature exploring long-term changes in people’s acceptance of homosexuality. Andersen and Fetner (Reference Andersen and Fetner2008a) and Lewis and Gossett (Reference Lewis and Gossett2008) associate the changes with the arrival of new cohorts. As Loftus (Reference Loftus2001) and Lee and Mutz (Reference Lee and Mutz2019), our results indicate that education plays an important role in reducing rejection toward homosexuality. Nevertheless, they also highlight the role played by a decrease in religiosity and increased contact with gays and lesbians, which is a variable that is not available in our database. Despite our evidence on the role of some of the socioeconomic variables included in our model influencing progress in the acceptance of homosexuality in Chile, there are further considerations that could complement our understanding of this social change. First, we cannot control for those variables that are not available—or not so with sufficient quality—in our database and, naturally, those macro factors affecting everyone whose effect the intercept absorbs in our framework. Footnote 6 Therefore, acceptance of homosexuality in Chile might be influenced either by variables other than those analyzed here or by changes in the effects of such variables concerning the acceptance of homosexual relationships.

We draw from the relevant theoretical and empirical literature, particularly cross-country studies that provide insights into the significance of national features. We make an educated guess about the potential role of those factors that we could not include in the quantitative analysis and the impact they might have had in increasing acceptance of homosexuality. Basically, we resort to the literature that addresses the main drivers of acceptance of homosexuality, giving priority to cross-country studies assessing the impact of country-level variables. Footnote 7 Then, we check how Chile has evolved in the domains we can identify in those works during the period of interest to determine whether those variables might have played a role in explaining the shift in attitudes in the country from 1998 to 2018.

Regarding omitted variables, an obvious element involves the enactment of different national laws and regulations since 1998 to 2018 designed to reduce homophobic behavior and conduct. As mentioned earlier, empirical evidence reveals that this factor could shape levels of acceptance of homosexuality (Hooghe and Meeusen Reference Hooghe and Meeusen2013; Slenders, Sieben, and Verbakel Reference Slenders, Sieben and Ellen Verbakel2014). Actually, a nonnegligible part of the relevant legal changes (e.g., same-sex marriage and adoption) in Chile materialized only after 2018, which suggests that they can be actually a consequence of the impressive shift in the attitudes toward homosexuality in the country.

Second, previous studies highlight the role of economic development in boosting the acceptance of same-sex relationships (Peffley and Rohrschneider Reference Peffley and Rohrschneider2003; Andersen and Fetner Reference Andersen and Fetner2008b; Adamczyk and Cheng Reference Adamczyk and Alice Cheng2015; Hadler Reference Hadler2012; Hooghe and Meeusen Reference Hooghe and Meeusen2013; Jäckle and Wenzelburger Reference Jäckle and Wenzelburger2015; Janssen and Scheepers Reference Janssen and Scheepers2018; Zhang and Brym Reference Zhang and Brym2019). Footnote 8 It seems not only that poorer nations are more likely to repress homosexuality more severely (Encarnación Reference Encarnación2011), but also that a low social status engenders high levels of distress (Persell, Green, and Gurevich Reference Persell, Green and Gurevich2001), fueling greater rejection or the perception of gay and lesbian individuals as potential competitors for limited public resources (Hadler Reference Hadler2012). This appears to be a plausible driver of the dramatic decrease in homophobia in Chile, as the country experienced an economic growth rate well above the regional average during the period 1998–2018, raising its adjusted net real income per capita by almost 80 percent (World Bank 2022).

Third, the evolution of inequality in Chile is also consistent with the insights in prior works. Although unequal outcomes and opportunities are a long-standing problem in Chile, the country made remarkable progress in this respect from 1998 to 2017: the Gini index fell from 55.5 to 44.4 (World Bank 2022). Footnote 9 Similarly, inequality in education decreased during the period of analysis. For instance, according to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC 2021), while in 2000 school attendance among the population age seven to twenty-four years old was roughly 11 percent higher in the top quintile of income than in the bottom one, by 2017 the gap was barely 1 percent.

In the fourth place, Chile’s trajectory in terms of economic freedom is also in line with the correlation between this variable and the population’s view of homosexual relationships suggested in prior studies. For instance, Berggren and Nilsson (Reference Berggren and Nilsson2013) suggest that economic freedom, especially in the long run, is positively correlated with acceptance of homosexuality. Likewise, and all other things being equal, increased economic competition helps reduce gender wage gaps (Weichselbaumer and Winter-Ebmer Reference Weichselbaumer and Winter-Ebmer2007). According to the measure proposed by the Fraser Institute (2022), economic freedom in Chile grew by around 6.5 percent from 1995 to 2018, rising from 7.47 to 7.96 out of 10 points.

Regarding the quality of democracy, which cross-country investigations associate with higher levels of acceptance (Peffley and Rohrschneider Reference Peffley and Rohrschneider2003; Corrales Reference Corrales2017; Janssen and Scheepers Reference Janssen and Scheepers2018; Zhang and Brym Reference Zhang and Brym2019), our variable on confidence in institutions might not fully capture the extent of such a relationship. Footnote 10 In this respect, Chile improved in this area during the period of interest. For instance, the country made some progress in terms of the Egalitarian Democracy Index, which rose from 0.58 in 1998 to 0.63 in 2018 (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Fish, Glynn, Hicken, Luhrmann, Marquardt, McMann, Paxton, Pemstein, Seim, Sigman, Skaaning, Staton, Wilson, Cornell, Alizada, Gastaldi, Gjerløw, Hindle, Ilchenko, Maxwell, Mechkova, Medzihorsky, Römer, Sundström, Tzelgov, Wang, Tore and Ziblatt2020), which has some support in the specialized literature (Navia Reference Navia2010; Ruiz Reference Ruiz, Daniel and Molina2009). Similarly, although many authoritarian enclaves persisted in 1998 (Garretón Reference Garretón1999), by the end of the 2010s they had been almost completely dismantled (Garrido-Vergara Reference Garrido-Vergara2020; Loxton Reference Loxton2021). Moreover, Chile seems to have experienced a noteworthy awakening in terms of political activism and claims for civil rights (Donoso and von Bülow Reference Donoso and von Bülow2017), another driver of acceptance highlighted in this literature.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that some studies suggest that individuals’ view on abortion and gender equality might contribute to increased acceptance of same-sex relationships (van der Toorn et al. Reference van der Toorn, Jost, Packer, Noorbaloochi and Van Bavel2017; Janssen and Scheepers Reference Janssen and Scheepers2018). Nevertheless, while this association is highly credible, it is also very likely that these sorts of beliefs are jointly determined; therefore, even though they were available in our database, their inclusion in the econometric analysis would not be advisable as long as one argues that they are endogenous variables.

In sum, there are several state-level factors in Chile that our econometric analysis confines to the intercept, which evolved in a consistent way with improved attitudes toward same-sex relationships.

The possible role of changes in these variables is in line with World Society Theory, whereby global norms, through institutions, provide a common framework for individuals to deal with social changes. In the long term, this framework tends to determine cultural patterns that include, among others, democratization, economic openness, and acceptance of diversity (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Boli, Thomas and Ramírez1997; Symons and Altman Reference Symons and Altman2015). In the Chilean case, this explanation is consistent with the tendency toward more inclusive legislation, which includes new laws protecting homosexual relationships.

The second issue, the role of changes in the impact of omitted variables in explaining the progress in acceptance of homosexuality in Chile, would be in tune with cultural theories, such as postmaterialist theory (Inglehart and Flanagan Reference Inglehart and Flanagan1987; Inglehart Reference Inglehart1990, Reference Inglehart1997), which argues that greater acceptance of same-sex relationships is due to the spread of liberal values brought about by greater democracy, economic growth, and modernization. As people are increasingly able to satisfy their material needs, they shift their attention to social issues, including acceptance of sexual diversity (Andersen and Fetner Reference Andersen and Fetner2008b). In other words, the aforementioned variables might be part of the explanation of progress in the acceptance of homosexuality not only because of changes in their levels but also because their relevance may have increased over the years.

It is therefore logical to assume that the change attributed to the intercept of our model could be explained by changes in the levels of omitted variables, by changes in their impact, or, more likely, by a combination of the two.

Conclusions

This article has explored the drivers of the increase of in acceptance of homosexual relationships in Chile between 1998 and 2018. Specifically, it has devoted much attention to the role of individual socioeconomic variables (gender, location, birth cohort, age, level of education, religiosity, political orientation, and social capital) in this change. The contribution of this work is twofold. First, to our knowledge, ours is the first study on the evolution of long-term attitudes toward homosexuality outside the United States and Canada. Second, we illustrate the application of a nonlinear version of the so-called Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition to analyze shifts in citizens’ views on hot topics in public opinion surveys.

Drawing on two waves of the ISSP, our analysis has shown that changes in observable individual characteristics accounted for 3.7 out of 32.5 percentage points of the acceptance of homosexuality. Specifically, educational attainment and birth cohort played a significant role in explaining the evolution of the dependent variable: the increase in schooling levels from 1998 to 2018 (a total of 24.7 percent) and generational replacement raised acceptance of homosexual relationships by 2.6 percentage points. This represents 11.4 percent of the total change and a 68.5 percent increase over the level in 1998 (5.4 percent). Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that the power of social trust to curb rejection seems to have decreased in the twenty years of our analysis.

Nonetheless, this research also points out the need for complementing the explanation of the changes in acceptance by assessing the relevance of the variables omitted from our model, especially those concerning structural and macro-level factors.

These findings, where most of the variation in attitudes toward homosexuality does not respond to individual socioeconomic characteristics, are therefore consistent with world society theory (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Boli, Thomas and Ramírez1997; Symons and Altman Reference Symons and Altman2015), which focuses on the effects that global cultural processes have on the homogenization of social values. In addition, another relevant measure for understanding Chile’s evolution would be to assess changes in the effects that the aforementioned (omitted) variables have on the acceptance of same-sex relationships. Regarding this, Inglehart’s postmaterialist theory (Inglehart & Flanagan Reference Inglehart and Flanagan1987; Inglehart Reference Inglehart1990; Inglehart and Baker Reference Inglehart and Baker2000) sheds some light on how developed societies with liberal values prompted by the spread of democracy and modernization increase the acceptance of same-sex relationships.

In summary, although we document the importance of individual socioeconomic variables in explaining the increase in the acceptance of homosexuality in Chile over the period 1998–2018, our results also suggest that the structural changes during this period that were not linked to individual-level characteristics might have played a substantial role.

Last, we should bear in mind some of the limitations of this work and possible pathways for further research. As to limitations, the sample sizes of the surveys used for our analysis are not large. This might hamper the likelihood of identifying the role of other potentially relevant socioeconomic covariates in the quantitative analysis. Another finding is that national-level factors can be more important than we might tend to assume in explaining the trends in these kinds of variables, due to citizens’ views. It would be interesting to apply this methodology to other national cases, with different institutional and cultural traditions, which have also witnessed considerable progress in the acceptance of homosexuality.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/lar.2023.7

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Hugo Marcos-Marné for his comments on a previous version of this paper.