The research reported herein was pursuant to a grant from the U.S. Social Security Administration (SSA) funded as part of the Retirement and Disability Research Consortium. The findings and conclusions expressed are solely those of the authors and do not represent the views of SSA, any agency of the federal government, The New School for Social Research, or Boston College. Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of the contents of this report. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply endorsement, recommendation or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof. The authors thank James Giles for excellent research assistance.

1. Introductory statement

Working longer helps people secure a comfortable retirement, particularly given the rise in Social Security's full retirement age (Munnell and Sass, Reference Munnell and Sass2008; Bronschtein et al., Reference Bronschtein, Scott, Shoven and Slavov2019). Before the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) crisis, many older workers had internalized this message, and both retirement and Social Security claiming ages were steadily rising (Hou et al., Reference Hou, Munnell, Sanzenbacher and Li2020; Chen and Munnell, Reference Chen and Munnell2021). However, the COVID-19 pandemic may have interrupted this trend. Hence, the object of this paper is to assess whether COVID-19 caused a wave of early retirements and – if so – whether certain groups of workers were disproportionately affected.

That some older workers left their jobs during a pandemic and global recession is to be expected. Indeed, others have shown that the retired share of the population rose in 2020 (Faria e Castro, Reference Faria e Castro2021). Still, questions remain over whether these impacts are likely to dissipate as the pandemic recedes and the economy recovers – or whether a more permanent exodus from the labor force is to be anticipated in the coming years. As a first step toward answering these questions, this study examines workers' transition out of work and into retirement during the first year of the pandemic. Specifically, the analysis uses the panel structure of the monthly Current Population Survey (CPS) to construct annual hazard rates of leaving work and of retirement for individuals ages 55 to 79, comparing individuals observed during the first year of the pandemic (April 2020–March 2021) to those observed during a similar period before the pandemic.

The paper reaches three main conclusions. First, the pandemic did indeed push many older workers out of their jobs, but the impact on employment was unevenly distributed.Footnote 1

Workers with less than a college degree were more likely to leave than the more highly educated; Asian–Americans were more likely to leave than other racial groups; part-time workers and those whose occupations required high physical proximity to others were more likely to leave than full-time workers and those who could socially distance. Consequently, some groups did not experience a significant disruption to employment during the pandemic, while others left work in large numbers.

Second, the pandemic induced a large discrepancy between leaving work and retiring. The hazard of leaving work was nearly 6.7 percentage points higher during the pandemic than in the preceding year (a 43-percent increase over the pre-pandemic baseline); whereas the hazard of self-identified retirement increased by only 1 percentage point (a 12-percent increase). The increased likelihood of retirement was not significantly different across demographic groups, except those over age 70 and part-time workers who saw an increase in the likelihood of retirement. Finally, the pandemic had little impact on Social Security Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) claiming – a consequence of the muted effect on retirement and its concentration among those already likely to have claimed benefits. This trend has continued into the first half of 2022.

Ultimately, while the pandemic pushed many workers out of the labor force, there was no immediate retirement boom for full-time workers under 70. The fact that many older workers left their jobs but not did not retire could mean that they wanted to return to work when restrictions eased, temporary layoffs ended, and vaccination made it safe to do so. The subsequent rebound in employment during the second year of the pandemic supports this interpretation (Goda et al., Reference Goda, Jackson, Nicolas and Stith2022), though whether the improved outcome for older workers was due to flows into employment from unemployment or non-participation is unclear. Other studies have found a steady increase in retirement through 2022, suggesting that older workers had trouble fulfilling their plans to re-enter the workforce when the pandemic waned (Forsythe et al., Reference Forsythe, Kahn, Lange and Wiczer2022; Montes et al., Reference Montes, Smith and Dajon2022). Although these studies do not examine part-time older workers specifically, they affirm our finding that retirement transitions increased most among the very oldest workers.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. The next section describes the current state of research on the labor-market impacts of COVID-19, as well as lessons from previous recessions. Section 3 details the data and methods of the analysis. Section 4 presents results, and the final section concludes.

2. Literature review

A rapidly growing literature examines how the COVID-19 pandemic affected the employment of different segments of the U.S. labor market. Naturally, researchers' understanding of the pandemic is evolving in real-time as the pandemic itself evolves and new data become available.

At present, only a handful of studies examine the labor force participation of older workers during the pandemic. All of these studies analyze the same data – the monthly CPS – and find that the pandemic pushed many older workers out of their jobs. Some studies conclude that older workers were not disproportionately affected relative to younger age groups (Munnell and Chen, Reference Munnell and Chen2021; Sanzenbacher, Reference Sanzenbacher2021), while others conclude the opposite (Bui et al., Reference Bui, Button and Picciotti2020; Jacobson et al., Reference Jacobson, Feder and Radley2020; Coile and Zhang, Reference Coile and Zhang2022). The main difference between these studies is their definition of ‘older worker’ –55- to 64-year-olds look qualitatively similar to prime-age workers, with any disproportionate job separations occurring among workers ages 65 and older. Intuitively, the oldest workers are not only affected by adverse labor market conditions but are also more susceptible to the virus itself and so may be more likely to reduce their labor supply. Yet it is still worth analyzing this younger group of workers, ages 55–64, since a considerable share of workers in this age group do ordinarily retire. This group is also relevant to the oft-repeated claims, both among policymakers and in popular media, of a wave of ‘early’ retirements brought on by the pandemic.

Beyond age, this nascent literature has only begun to explore whether specific factors were associated with some older workers (defined in this paper as ages 55 to 79) leaving the labor force. Research on the prime-age workforce suggests that socio-demographic characteristics and job conditions played a role. On the demographic side, studies have shown that women suffered greater employment losses than men, and that Hispanic and Asian–American workers were more likely to leave employment than white workers.Footnote 2 Regarding job conditions, workers without a college degree fared worse than the college educated, and the ability to work remotely from home has emerged as a great differentiator, due to business-capacity restrictions and personal fears of virus exposure (Angelucci et al., Reference Angelucci, Angrisani, Bennett, Kapteyn and Schaner2020; Béland et al., Reference Béland, Brodeur and Wright2020; Brynjolfsson et al., Reference Brynjolfsson, Horton, Ozimek, Rock, Sharma and Yi2020; and Borjas and Cassidy, Reference Borjas and Cassidy2020).Footnote 3 Additionally, evidence from consumer location data suggest that local economic activity slowed more in high-density areas due to peoples' fear of catching the virus (Goolsbee and Syverson, Reference Goolsbee and Syverson2021).Footnote 4 A recent study by Goda et al. (Reference Goda, Jackson, Nicolas and Stith2021) documents similar patterns in the stock of older individuals in the workforce.

To what extent displaced older workers will ultimately end up re-entering the labor force also remains unanswered. A few studies note that self-reported retirement has increased during the pandemic, but not at the same pace as job loss (Coibion et al., Reference Coibion, Gorodnichenko and Weber2020; Kaplan et al., Reference Kaplan, Atkinson, Dolmas, Giannoni and Mertens2021; Kolko, Reference Kolko2021; and Sanzenbacher, Reference Sanzenbacher2021). Interestingly, the Social Security OASI program did not see a concurrent increase in claims in the spring and summer of 2020 (Glenn, Reference Glenn2020; and Goda et al., Reference Goda, Jackson, Nicolas and Stith2021). The reasons for this discrepancy between workforce exit and OASI claiming have not yet been pinned down, but could include the closure of SSA field offices, federal policies such as extended unemployment benefits and stimulus checks, or a reluctance on the part of older workers to consider themselves permanently out of the labor force. Meanwhile, Nie and Yang (Reference Nie and Yang2021) indicate that current retirees were less likely to re-enter the workforce during the initial phase of the pandemic, but that pattern may start to reverse as labor markets have tightened in recent months.

While older workers also left the labor force during the Great Recession, research from that period is unlikely to shed much light on current trends. In 2008, many older workers wanted to delay retirement to let their financial assets recover from the stock market crash, but found it difficult to work longer due to high unemployment.Footnote 5 Ultimately, the lack of suitable jobs outweighed the desire to work.Footnote 6 By contrast, during the first year of the pandemic, workers with retirement accounts saw their balances increase, and the labor market recovered quickly to pre-pandemic tightness.Footnote 7

Given how much remains unknown about older workers and COVID-19, this paper has three goals. First, it documents the factors that made older workers more or less susceptible to pandemic job separations. Second, it determines whether the workers who were pushed out of the labor force were also more likely to self-report retirement. And third, it reconciles these patterns with recent trends in Social Security retirement claiming.

3. Data and methodology

Most of the analysis in this study uses the CPS, a monthly survey of a large sample of U.S. households that collects information about labor force status and other economic outcomes. Respondents are in the monthly CPS sample over 2 periods exactly one year apart: they are surveyed in each of 4 consecutive months, then are out of the survey for 8 months, but re-enter the survey the next calendar year during the same 4 calendar months as the previous year. For example, a respondent may be surveyed by the CPS in March–June 2019, and then again in March–June of 2020.

Though the CPS is designed as a cross-sectional survey, researchers have constructed techniques to connect the interviews for any one respondent, allowing for longitudinal analysis.Footnote 8 The focus of this study's longitudinal analysis is on individuals ages 55 to 79, and how their labor force status changes between their 4th month in the survey and their last month in the survey, which occurs one year later.Footnote 9 Specifically, we compare the experience of two groups of workers: the ‘pre-pandemic group’ has both their initial and final interviews before April 1, 2020 (initial interviews between January 2017 and March 2019 and follow-up interviews between January 2018 and March 2020), while the ‘post-pandemic group’ has their initial interview between April 2019 and March 2020, with follow-up interviews during the pandemic period: April 2020–March 2021.

For each group of workers, we conceptualize labor-force transitions in two ways. First, we examine the rate of employment exit by focusing on a sample of people who are working at the time of the 4th-month interview, and create an indicator equal to one if the respondent switches to not working in the final month.Footnote 10 Second, we examine an indicator equal to one if the respondent reports not being in the labor force in the final month because they are retired.

We assume that the post-pandemic group would have behaved similarly to the pre-pandemic group had COVID-19 not occurred, and broadly attribute any differences in behavior to the pandemic. This assumption implies that there were no major confounders that would have changed the later group's behavior in the absence of COVID-19. We believe this is safe assumption, as we are unable to conceive of any other factors that would have caused sudden changes in employment and retirement behavior in 2020–2021, in particular the sharp relative changes in outcomes between demographic groups that we document below.

Of course, a key methodological choice is how to define the pre-pandemic group so that it best reflects counterfactual behavior. As will be shown in the next section, labor markets were quite tight in the months preceding April 2020, with fewer employment separations than typical during the two years previous. For this reason, the analysis broadly defines the pre-pandemic group as those whose final interview occurred between January 2018 and March 2020; fortunately, separation and retirement trends were quite flat during this period, so limiting the pre-pandemic group to those interviewed in the year before the pandemic does not change the story. The sample used in the analysis is large: among those ages 55–79 with a valid match between the 4th and 16th months in the survey, nearly 53,000 CPS respondents were working in the initial month.

As one of the first analyses of how the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced the labor supply of older individuals, this study addresses a broad question: who was most likely to leave employment and retire during the first year of the pandemic? Hence, the analysis focuses on several circumstances under which individuals may have been induced to retire.

3.1 Age and health

The first circumstance reflects individual capacity and comfort with continued work. Age is expected to push workers out of the labor force for two main reasons: first, because older individuals especially were told to maintain strict social distancing; and second, because workers who are eligible to claim Social Security may not need to continue working. Age (for the individual and their spouse) is coded as a series of dummy variables (55–59; 60–61; 62–64; 65–69; and 70–79) reflecting age-eligibility for Social Security. Due to data limitations, health status in this analysis reflects severe limitations of activity: any reported difficulty with hearing, vision, memory, physical activity, mobility, or personal care. Future research could focus on medical conditions related to COVID-19, such as respiratory issues, obesity, and diabetes, and use data sources with more detailed health measures.

3.2 Demographics

The second circumstance is the unequal effect of the pandemic by demographic group. Prior research has established that the pandemic and accompanying recession have had a disproportionate impact on women and persons of color. Therefore, the analysis examines changes in labor force status by gender, race, and Hispanic origin.

3.3 Working conditions

The third circumstance is working conditions during the pandemic. One specific variable of interest is the worker's ability to work remotely or ‘telework.’ The analysis proxies for this ability by using the measure designed by Dingel and Neiman (Reference Dingel and Neiman2020) to create an indicator variable for whether the respondent is in an occupation (at their initial interview) where work can be done remotely. A greater ability to work remotely should be associated with the respondent being less likely to leave work or retire. Relatedly, the analysis considers whether the worker's occupation requires high physical proximity to others, a binary measure from Mongey et al. (Reference Mongey, Pilossoph and Weinberg2021). More generally, better-educated workers may have advantages beyond the flexibility to work remotely that may have helped them avoid early retirement, so education is also included in this set of factors. In addition, the analysis accounts for whether the individual is employed part-time or self-employed. Part-time workers are expected to be less attached to the workforce and more likely to retire. The impact on the self-employed is ambiguous: they have greater autonomy to adapt their work environment, but may have had to shut down their small business due to quarantine or slack demand.

3.4 Local conditions

The fourth and final circumstance is the severity of both the pandemic itself and economic conditions around the associated recession. To capture the risk of the pandemic, the analysis accounts for the peak monthly share of the population (per thousand) who died from COVID-19 in the respondent's county, as well as the county's population density (due to greater perceived risk of infection in large cities).Footnote 11 The analysis includes state-month-year fixed effects ($\varsigma _{s, t}$![]() ) to reflect the changing conditions in the respondent's state over time.Footnote 12

) to reflect the changing conditions in the respondent's state over time.Footnote 12

The analysis estimates a linear regression model where the dependent variable is, in turn, an indicator for leaving employment or for a change in reporting status to retired. The regression model is:

where P t+12 is an indicator equal to one if the respondent is in the post-pandemic group, which denotes the respondents whose labor market decisions were affected by the pandemic.

The vector of coefficients γ reflects how the four sets of circumstances described above were associated with labor-force exit before the pandemic. These X i,t variables are measured as of the respondents' first interview (time t). The circumstances are then interacted with the pandemic indicator (P t+12) to estimate how the relationships changed during the pandemic. A positive coefficient on an un-interacted variable indicates that the factor is positively associated with employment exit or retirement under normal circumstances. A positive interaction effect (θ) indicates that the factor is associated with greater exit or retirement during the pandemic, relative to normal circumstances. Hence, these interaction effects are the focus of this study.

A key limitation of the monthly CPS is that it does not ask about Social Security benefit receipt. In order to relate our analyses of employment and retirement to recent trends in claiming, we supplement the CPS with an examination of administrative data from the SSA on monthly applications for OASI benefits.Footnote 13 The monthly claiming rate is calculated as the number of applications relative to the 2019 population ages 55 or over.

If the regression results show significant employment transitions but no change in self-reported retirement or Social Security claiming, older individuals may be out of work, but not think of themselves as retired. Older individuals who planned to return to work after vaccination and the easing of COVID-19 restrictions may have decided not to claim Social Security benefits, which could feel like a more permanent retirement decision. Although beneficiaries can opt to suspend benefits after finding a new job, they may not be aware of that option, or they may misunderstand the Social Security earnings test as restricting their ability to return to work.

4. Results

This section first discusses how the probability of moving out of employment has changed overall, from the pre-pandemic to the post-pandemic periods, and then presents regression results that indicate which groups of older workers were more likely to leave their jobs in the past year. It then discusses how retirement patterns have changed, with similar attention to the individuals most likely to retire during the COVID-19 crisis. Lastly, it assesses preliminary evidence on Social Security claiming.

4.1 Leaving employment

Figure 1a examines the share of older individuals who were working when first sampled by the CPS, but no longer working 12 months later; the x-axis labels the month of the last interview. Before the COVID-19 outbreak, about 15 percent of older individuals would leave employment within a year. The separation hazard increased sharply in April 2020 to 31.4 percent. In subsequent months, a lower percentage of older people left work – even by May 2020, the hazard fell back to 25.6 percent – but it remained near or above 20 percent throughout the rest of 2020 and the beginning of 2021. Overall, the share of people ages 55 to 79 who left the workforce during the pandemic increased by a statistically significant 6.7 percentage points, an increase of 43 percent over the pre-pandemic hazard rate.

Figure 1. Share of older workers leaving their jobs over the course of a year, 2018–2021.

Source: Authors' estimates from the Current Population Survey (2018–2021). a. Share leaving their jobs. b. Share retiring.

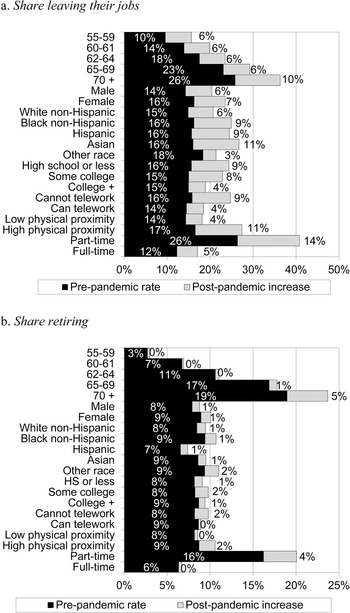

To set the stage for the regression results, Figure 2a tabulates the raw data to show which groups were more likely to leave employment before the pandemic, and which groups saw the largest increases (without controlling for other characteristics). The results are consistent with previous findings in the literature. Employment exits rose more during the pandemic for those age 70 or older compared to younger ages; for women more than men; for Asian–Americans more than other racial groups; and workers with only a high school diploma more than college graduates. Not surprisingly, those who had high-contact jobs and those who could not work remotely were much more likely to exit employment during the pandemic, as were part-time workers.Footnote 14

Figure 2. Share of older workers leaving their jobs over the course of a year, by worker attributes, 2018–2021.

Source: Authors' estimates from the Current Population Survey (2018–2021). a. Share leaving their jobs. b. Share retiring.

Although some of these differential changes are large, older workers are often members of multiple groups, so it is important to disentangle which characteristics are most associated with leaving employment. (Appendix Table A1 shows summary statistics for independent variables.) We therefore turn to the regression results. For expositional clarity, the main body of the paper focuses on the interaction coefficients in Table 1, while the full regression results are available in Appendix Table A2. The main (pre-pandemic) estimates in Table A2 are largely as expected: the likelihood of leaving employment increases with age, and the spouse's age, and is higher for women, Black workers, and those with health problems.Footnote 15

Table 1. Regression results for the effect of the pandemic on job separations and retirement, by worker characteristics, April 2018 – March 2021

Notes: Standard errors not shown are clustered at the county level. *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.1.

Source: Authors' estimates from the Current Population Survey (2018–2021).

As suggested by some previous studies, age was not a major predictor of pandemic-induced separation; pre-pandemic, workers ages 60–64 (as well as 65–69) were more likely to leave their jobs than workers ages 55–59, but the differential between age groups held steady during the pandemic (Table 1, first column). One exception are workers ages 70 or older: all else equal, this oldest group saw a 2-percentage-point increase relative to the ages 55–59 group, but this difference is not statistically significant. Another variable associated with work capacity or comfort with working shows a more surprising result: the association between certain severe health problems and employment exit actually declined by about 3 percentage points during the pandemic. One caveat is that, due to limitations with the monthly CPS questionnaire, the health problems included in this variable are not particularly related to COVID-19 – they represent severe limitations in general, rather than more specific risk factors such as respiratory issues, obesity, or diabetes that put older individuals at greater risk of severe outcomes from coronavirus infection.

In general, gender and race/ethnicity were not strongly associated with greater employment exit during the pandemic's first year. One exception is being Asian–American, which was associated with an increase of nearly 5 percentage points in the hazard out of employment, compared to identifying as white non-Hispanic. Being Black or Hispanic, in contrast, was not associated with an increase in employment exits (compared to being white) after controlling for other differences.

Certain employment conditions also seem to be important. The increase in employment exit was about 3.2 percentage points smaller for college graduates than for workers without a college degree. More specifically, workers whose jobs required high physical proximity were 5.3 percentage points more likely to leave employment during the pandemic than those whose jobs allowed for social distancing. And part-time workers were 8.3 percentage points more likely to leave employment during the pandemic than their full-time counterparts.Footnote 16 Surprisingly, the increased likelihood of leaving employment during the pandemic was only about 1.2 percentage points less for those who had access to telework, and this result is not statistically significant. The self-employed were no more likely to leave employment during the pandemic after controlling for these other factors.

The local severity of the pandemic and its associated recession, however, seem to have had little impact on the share of older individuals leaving employment. Living in a county where the peak death rate was higher is associated with a higher hazard out of employment, but not by a statistically significant margin. As expected, living in a county with greater population density is marginally associated with greater increase in employment exit, all else equal. The state-time interactions capture the majority of the policy response to COVID-19, such as state-level shutdown orders.Footnote 17

4.2 Retirement

The above results indicate a greater increase in employment exit for those with less than a college degree, Asian–Americans, part-time workers, and those whose jobs make social distancing difficult. For individuals ages 55 to 79, leaving the workforce is usually associated with the decision to retire, whether voluntarily or involuntarily. But the pandemic was not associated with a large increase in the share of previously employed older individuals who report being out of the labor force due to retirement.

Figure 1b plots the overall trend in being out of the labor force due to retirement, among older individuals who were employed during their initial CPS interview. The trend is largely flat: the average retirement rate before the pandemic (through March 2020) is 8.4 percent, compared to 9.4 percent post-pandemic. That 1-percentage-point difference is statistically significant, but small compared to the effect on employment.

Figure 2b shows the (unadjusted) increase in the likelihood of retiring over the course of a year for different groups of older workers. While every subgroup experienced an increase in their retirement hazard, these increases are small relative to the effects on employment. As expected, pre-pandemic retirement hazards rose monotonically with age, but for age groups younger than 65, these hazards changed only minimally during the pandemic. In contrast, those ages 70–79 saw a 4.7 percentage-point increase. Patterns by gender, race, and education are largely absent. Workers in low-telework and high-physical-proximity occupations saw their retirement hazard increase by more than those in high-telework and low-physical-proximity occupations. The increase in the probability of retiring for part-time workers was 3.8 percentage points, more than ten times greater than the 0.35 percentage-point increase for full-timers.

Interestingly, Figure 2b suggests that many of the characteristics predicting employment exit during the pandemic did not similarly predict retirement. To confirm this finding, the second column of Table 1 reports the estimated coefficients from the interactions with the pandemic indicator, where the dependent variable is leaving the labor force due to retirement. Two of the interaction effects are large and statistically significant: the one for workers ages 70 or older, whose retirement hazard increased by 4.3 percentage points relative to the youngest age group; and the one for part-time workers, whose retirement hazard increased by 2.6 percentage points more than the increase for full-time workers. Additionally, high physical proximity on the job was weakly associated with an elevated risk of retiring during the pandemic. The other groups with statistically significant increases in their employment exit hazards – those with less than a college degree and Asian–Americans – did not see a commensurate change in their retirement hazard.

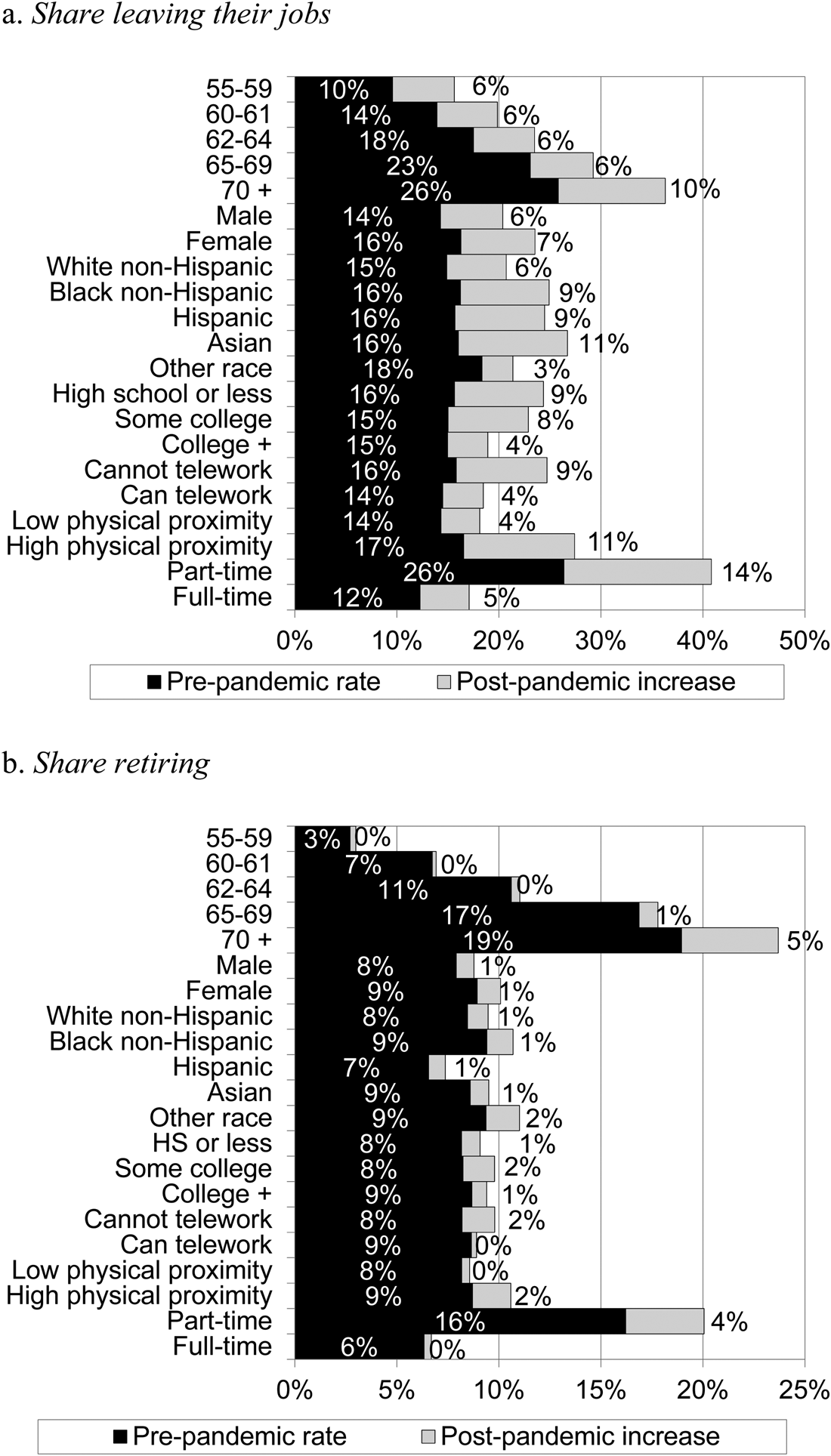

These regression results suggest no retirement boom for full-time workers under age 70, and Figure 3 confirms this interpretation. The figure shows how the retirement hazards for four groups of workers – those younger and older than 70, and either full or part-time – evolved during the first year of the pandemic. In particular, the retirement hazard for full-time workers under 70—a group that accounts for 74% of our older worker sample—held steady at 5.9%.

Figure 3. Share of older workers transitioning to retirement over the course of a year, 2018–2021.

Source: Authors' estimates from the Current Population Survey (2018–2021). a. Ages 55–69. b. Ages 70–79.

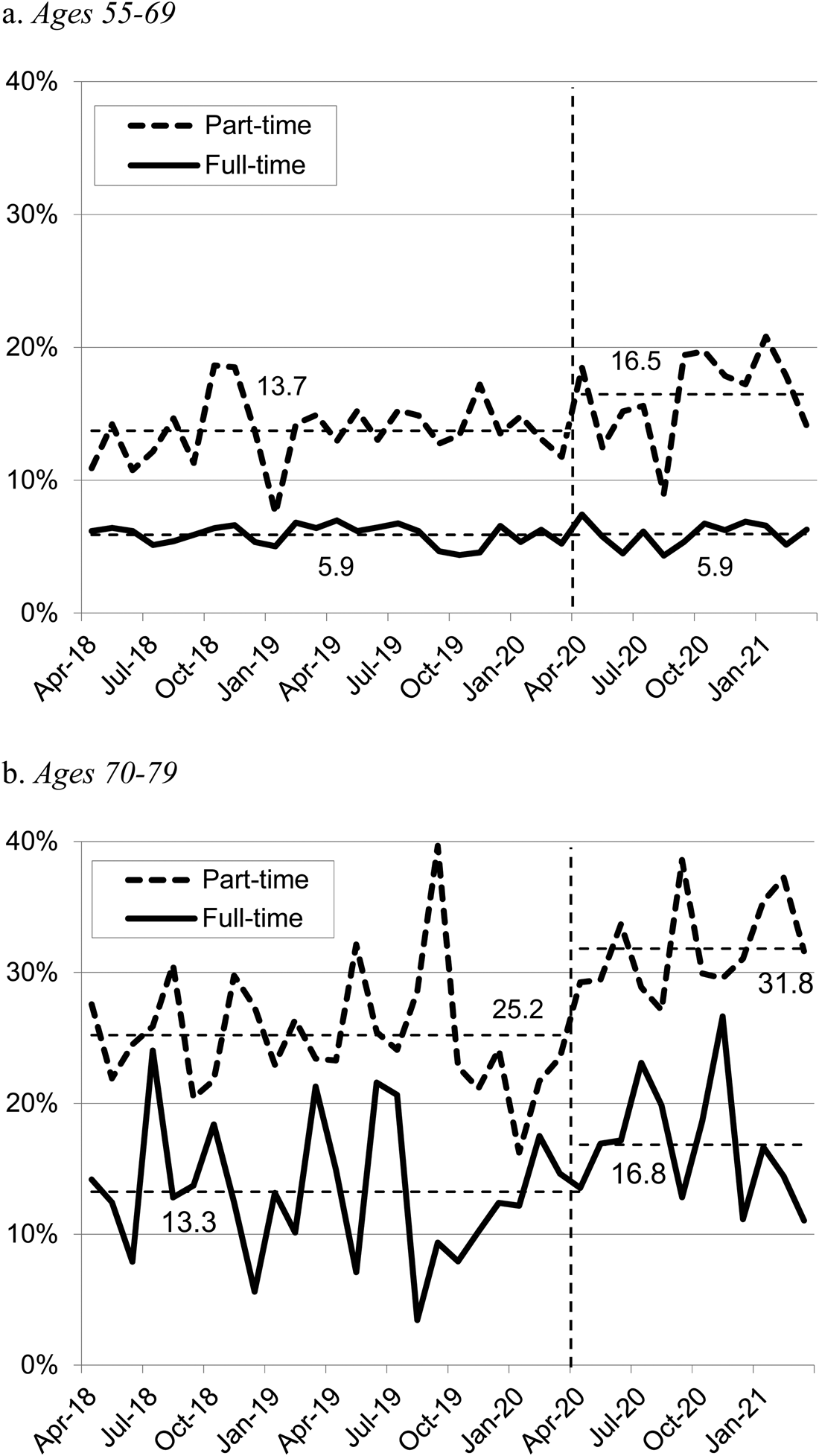

4.3 Social security claiming

The retirement patterns described above suggest only a small increase in OASI claims due to the pandemic, if any. Social Security's actuarial adjustment does not reward workers for delayed claiming past age 70, so virtually all workers in this age group had likely already claimed their benefits before the pandemic started. And similarly, a majority of part-time workers have claimed their benefits by age 65 (Ghilarducci et al., Reference Ghilarducci, Papadopoulos and Webb2020). Indeed, Figure 4 shows that the monthly claim rate for OASI remained roughly constant between January 2019 and April 2022.

Figure 4. Monthly OASI benefit applications relative to the population ages 55 and older, 2019–2022.

Source: Authors' calculations from Social Security Administrative Claims Data (2018–2022).

4.4 Robustness checks

To test the robustness of our results, we estimate several alternative specifications of our baseline models. The results of these robustness tests are reported separately for the two outcomes, employment exit and retirement, in Appendix Tables A3 and A4. Varying the fixed effects – year-month without state, state not interacted with time, and county instead of state – has little effect on the overall story. We also extend the observation window to 15 months by using respondents' first month-in-survey for the initial observation rather than their fourth month-in-survey, though relying on the first month-in-survey introduces rotation-group bias (Frazis et al., Reference Frazis, Robison, Evans and Duff2005). This change allows us to capture three additional months of pandemic outcomes, April through June 2021 (the last of these respondents had their initial CPS interviews in March 2020). For both employment exit and retirement, this change has little effect other than to reduce the magnitudes of the part-time coefficients, though they remain statistically significant. Finally, we drop all respondents in New York City, the epicenter of the pandemic's early days; these results differ little from the baseline specification.

5. Conclusion

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, many workers realized that working longer is an effective tool for improving retirement security, and retirement ages were steadily rising. Then, the pandemic upended nearly every aspect of life, work included. This paper explores how work, retirement, and Social Security retirement claiming changed during the first year of the pandemic, and what groups were most impacted.

The findings suggest a divergence between leaving work and retirement among older adults. On the one hand, employment exit among workers ages 55 to 79 dramatically increased during the first year of the pandemic. This trend was particularly pronounced among those with less than a college education, Asian–Americans, those whose occupations made social distancing difficult, and those who worked part time. On the other hand, self-identified retirement transitions increased more modestly over the past year. In particular, there was no retirement boom for full-time workers under 70 in the first year of the pandemic. This may explain why Social Security benefit claiming did not markedly increase.

This discrepancy between leaving work and retirement can be interpreted in two ways. Some older individuals may have intended to return to work once restrictions and temporary layoffs eased, and vaccination made doing so safer; the rebound in older employment found by Goda et al. (Reference Goda, Jackson, Nicolas and Stith2022) for the second year of the pandemic supports this interpretation. Others may never have intended to return to the labor force, but were using other sources of income – such as extended unemployment insurance or federal stimulus payments – to postpone claiming Social Security; the steady increase in retirements documented by Montes et al. (Reference Montes, Smith and Dajon2022) and Forsythe et al. (Reference Forsythe, Kahn, Lange and Wiczer2022) supports this interpretation.

The implications of these patterns for retirement security will depend on older workers' experience re-entering the workforce in the coming years. Pre-pandemic, displaced older workers were often challenged to find new jobs with comparable wages and benefits.Footnote 18 However, pandemic labor shortages may have given older workers new opportunities and bargaining power.Footnote 19 Additionally, the widespread transition to remote work arrangements may entice older workers and those with health limitations who desired more flexibility even before the pandemic.Footnote 20 Hence, for those who return to work, future research could investigate whether their new jobs provide comparable wages and benefits to their pre-COVID employment.

Additionally, it is as yet unclear whether those who self-reported as retired during the early pandemic will respond to tight labor markets by ‘unretiring.’ The role of part-time jobs in explaining pandemic retirements may play a role here. On the one hand, if these part-time jobs were predominantly bridge jobs serving as a transition into retirement, many who left the labor force may not come back. On the other hand, if retirement from full-time jobs is stickier than from part-time work, unretirement may also be easier for former part-timers. Early research on pandemic unretirement suggests that some COVID retirees will subsequently return to the workforce, but more time must pass before researchers can draw firm conclusions.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474747223000045.