In the decades leading up to the 1990s, Australia, along with many other Western countries, experienced cycles of public criticism about, and formal inquiries into, the quality and quantity of its mental health services. In response, a National Mental Health Policy was adopted by all Australian states, territories and the Federal government in April 1992 (Australian Health Ministers, 1992; Reference WhitefordWhiteford, 1993). The Policy, implemented through a 5-year National Mental Health Plan, became known as the National Mental Health Strategy. It represented the first attempt to coordinate nationally the development of public mental health services, which, since Federation in 1901, had been the responsibility of the eight state and territory governments.

METHOD

The Strategy addressed 12 priority areas (Table 1), with 38 objectives outlined in the Policy (Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, 2000a ). The structural reform of the services aimed to expand community-based services, reduce the reliance on ‘stand-alone’ psychiatric hospitals, mainstream acute beds into general hospitals and improve the quality of care and outcomes for consumers. To monitor implementation, a minimum mental health data-set was developed and an annual national survey collected these data from Commonwealth, state and territory governments and other sources. These performance indicators have been published annually in a national report since 1993 and the data collected for the most recent of these reports (Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, 2000a ) form the basis of this paper.

Table 1 Priority areas under the National Mental Health Strategy

|

Evaluation of the National Mental Health Strategy

In addition to the data collected annually to monitor the implementation of the Policy, an independent evaluation of the National Mental Health Strategy was conducted in 1997 (Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services, 1997). All available national data on mental health services in Australia were reviewed and three supplementary studies were undertaken: four area case studies of local populations assessed the impact of service changes, a national stakeholder survey was undertaken of peak organisations, and a commentary was commissioned from one of the authors (R. M.) to assess the appropriateness of the policy settings from an international perspective. The evaluation can be found at http://www.health.gov.au/hsdd/mentalhe/mhinfo/nmhs/nmhseval.htm.

RESULTS

Changes in service expenditure

In 1997-1998 expenditure for mental health services was AU$2.24 billion, which is about 6% of the country's health expenditure. This does not include services such as disability support or public housing, which, in Australia, are provided by departments other than the Department of Health. The expenditure for mental health services, therefore, is less than that reported by other countries. The Federal government share was 32%, the state and territory government share was 61% and the private sector share was 7%. Despite concerns that the Strategy would be ineffective in reversing a perceived erosion of mental health resources, total spending on mental health services increased by 30% between 1992 and 1998, in constant 1998 dollars. Federal expenditure increased by 55%, state and territory expenditure increased by 19% (13% in per capita terms) and private hospital sector spending increased by 32%.

However, the increases in state expenditure were not even (Table 2). Victoria, which in 1992 had the highest per capita expenditure of all states, experienced a period of budgetary crisis in 1993. The new government reduced mental health along with general health expenditure and the level of funding only recovered slowly in subsequent years. Late in the Strategy, concerted public criticism of the pace of reform in Western Australia saw its expenditure rise dramatically.

Table 2 Trends in per capita expenditure by states and territories, 1993-1998, expressed in constant 1998 dollars

| State | 1992/93 (AU$) | 1993/94 (AU$) | 1994/95 (AU$) | 1995/96 (AU$) | 1996/97 (AU$) | 1997/98 (AU$) | Growth (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New South Wales | 61.63 | 60.83 | 62.12 | 63.15 | 66.74 | 68.29 | 10.8 |

| Victoria | 77.09 | 72.48 | 75.25 | 76.88 | 77.90 | 77.15 | 0.1 |

| Queensland | 53.72 | 52.90 | 53.96 | 56.96 | 63.15 | 66.05 | 23.0 |

| Western Australia | 64.95 | 66.77 | 66.82 | 70.57 | 79.60 | 89.84 | 38.3 |

| South Australia | 68.83 | 70.04 | 69.05 | 67.68 | 75.00 | 80.80 | 17.4 |

| Tasmania | 67.04 | 70.31 | 71.71 | 76.82 | 77.62 | 77.86 | 16.1 |

| Australian Capital Territory | 55.15 | 53.37 | 55.55 | 58.31 | 64.14 | 61.76 | 12.0 |

| Northern Territory | 56.32 | 58.84 | 57.16 | 62.41 | 65.86 | 70.24 | 24.7 |

| Total | 65.07 | 63.78 | 65.05 | 66.79 | 70.98 | 73.32 | 12.7 |

Changes in public sector service mix

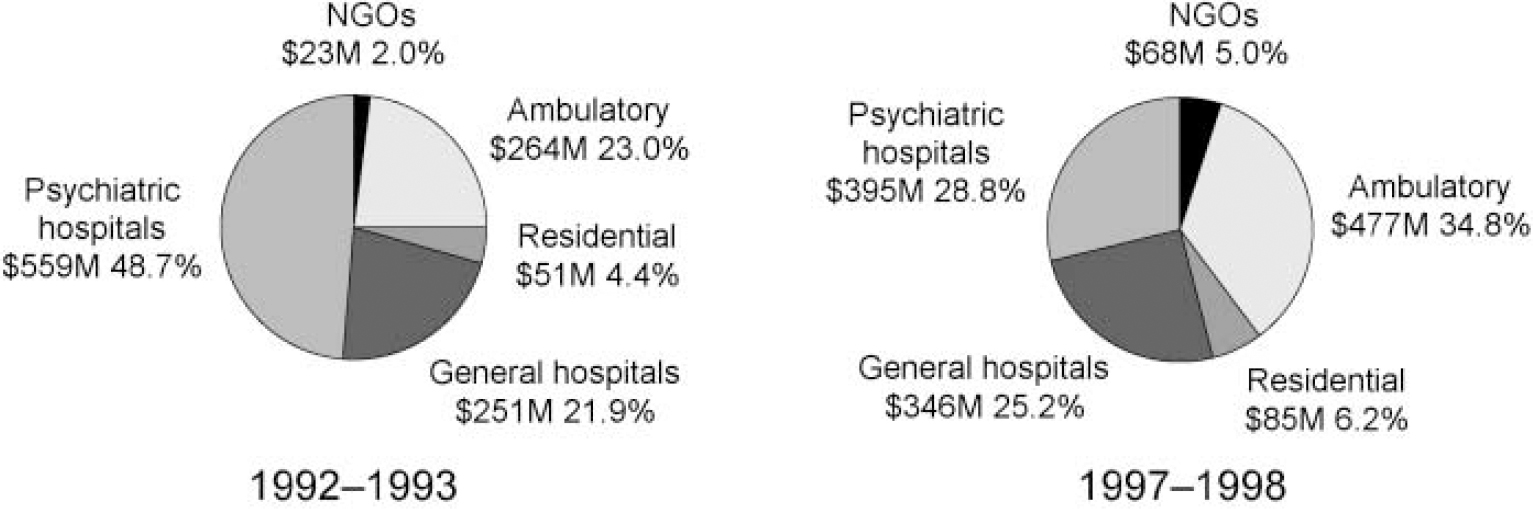

A substantial expansion occurred in community and general hospital services in parallel with a reduction in the size of stand-alone psychiatric hospital services (Fig. 1). In 1992-1993 only 29% of state mental health resources were directed towards community-based care and 73% of psychiatric beds were located in standalone hospitals that consumed half of the total mental health spending by the states and territories. Less than 2% of resources were allocated to non-governmental programmes aimed at providing support for people with a psychiatric disability in the community.

Fig. 1 National summary of changes in spending mix (AU$), 1993-1998. NGOs, non-governmental organisations.

Community-based service activity includes three components: ambulatory services consist of out-patient clinics, mobile assessment and treatment teams and day programmes; specialised residential facilities staffed by mental health professionals on a 24-hour basis provide accommodation in the community; and not-for-profit non-government organisations (NGOs) provide a wide range of accommodation, rehabilitation, recreational, social support and advocacy programmes. Between 1992 and 1998 state and territory spending on community mental health services grew by 87%, or AU$292 million in constant 1998 dollars. The NGOs increased their share of annual mental health expenditure from just under 2% to 5%.

The National Mental Health Strategy proposed the replacement of acute in-patient services traditionally provided in separate psychiatric facilities with units located in general hospitals. The number and size of psychiatric hospitals were to be reduced, with some long-term beds retained for those individuals who are unable to maintain their quality of life in less restrictive settings. It did not stipulate an optimum number or mix of in-patient services. This was to accommodate the different histories and circumstances of each state and territory, and the need for plans to be based on local population needs. In this sense the vision was national but the implementation was local. Overall, the number of public sector psychiatric beds decreased by 22% (1719 beds) between June 1993 and June 1998. In per capita terms, Australia reduced its psychiatric in-patient beds from 45.5 to 33.7 per 100 000 population over 5 years.

The stand-alone psychiatric hospitals were the focus of bed reductions, with overall numbers in these institutions declining by 41% (2406 beds), achieved mainly through the reduction in size of individual facilities rather than total hospital closures. By June 1998, beds located in stand-alone psychiatric hospitals accounted for 54% of Australia's total psychiatric in-patient capacity compared with 73% in June 1993. Nationally, the proportion of total state and territory mental health budget dedicated to the running of stand-alone hospitals decreased from 49% to 29%. The National Plan required resources released from institutional downsizing to be re-invested in alternative services and they provided approximately half of the additional funds used in the expansion of community services (Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, 2000a ).

The mainstreaming of acute beds into general hospitals was to bring mental health care into the same environment as general health care, thereby improving service quality and reducing the stigma associated with psychiatric care (Reference Whiteford, Macleod and LeitchWhiteford et al, 1993). At the commencement of the Strategy, 55% of acute psychiatric beds were located in speciality mental health units in general hospitals. By June 1998, this had increased to 73%, both as a result of a reduction in stand-alone acute services and a 34% growth in general hospital-based beds through the commissioning of new or expanded units. There emerged a consensus for public acute bed provision of between 15 and 20 beds per 100 000 population. No consensus on the provision of non-acute beds emerged (Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, 2000a ).

To move beyond historical funding and payments by diagnosis-related groups, a national mental health case-mix classification was developed with cost weights for speciality mental health services. This produced a model for describing the products of mental health care in terms of episodes of care, covering both in-patient and community services (Reference Burgess, Pirkis and BuckinghamBurgess et al, 1999). However, to date, there has been very little action to use this classification in developing our alternative funding model.

Changes in private sector services

In 1998 about one-third of Australians held private health insurance. Health insurance funding of private psychiatric hospitals grew by 32% over the 5 years, driven by growth in the number of private beds (20%) and increased throughput within the hospitals. By June 1998, private beds comprised 19% of the total psychiatric beds available.

Expenditure on services provided by private psychiatrists, funded under the national health insurance Medicare Benefits Schedule, grew by 6% annually in the decade prior to the Strategy. This growth rate slowed significantly during the Strategy and, by 1998, had begun to reverse (Table 3). Total Commonwealth expenditure on private psychiatrists in 1997-1998 was 3% less than in the preceding year.

Table 3 Expenditure and services per 1000 population by private psychiatrists funded under the Commonwealth Medicare Benefits Schedule, 1984-1998

| Year | Services per 1000 population | Expenditure (AU$ million) (constant 1998 dollars) |

|---|---|---|

| 1984/85 | 81.0 | 113.9 |

| 1985/86 | 85.0 | 118.9 |

| 1986/87 | 89.3 | 126.6 |

| 1987/88 | 90.1 | 133.9 |

| 1988/89 | 93.0 | 136.4 |

| 1989/90 | 99.1 | 146.6 |

| 1990/91 | 103.0 | 156.2 |

| 1991/92 | 108.7 | 169.5 |

| 1992/93 | 114.0 | 184.8 |

| 1993/94 | 119.9 | 198.6 |

| 1994/95 | 121.6 | 202.5 |

| 1995/96 | 123.4 | 204.9 |

| 1996/97 | 119.7 | 196.2 |

| 1997/98 | 116.8 | 190.5 |

One expectation of the Strategy was the rejuvenation of the public sector to help attract and retain psychiatrists. There was a 17% growth in the number of public sector medical staff between 1993 and 1998. With a relatively fixed supply of psychiatrists, the growth of private psychiatry reversed, with a plateauing and then a decline in the number of full-time psychiatrists in private practice billing under the Medicare Benefits Schedule. This suggests that strengthening the public sector can reverse the flow of psychiatrists to the private sector, even where this sector has uncapped reimbursement from national insurance. However, a substantial maldistribution of private psychiatrists continues to create access problems within metropolitan areas and between metropolitan and regional areas.

Consumer and carer involvement in services

To improve the quality and responsiveness of services to consumers, the Strategy required that consumers and carers be involved explicitly in service planning and delivery. In response, community advisory groups were established at national, state and territory levels. As part of the reporting arrangements under the Strategy, both public sector mental health services and community advisory groups provided information describing the arrangements in place for consumers and carers to participate in local service planning and delivery. Responses were grouped into four levels, based on the scope given to consumers and carers to participate (Table 4). Although the participation rates of consumers and carers improved, there remained many services that did not have the appropriate mechanisms in place.

Table 4 National trends in consumer participation in public sector mental health service organisation, 1994-1998

| Type of consumer participation arrangements | Description | Percentage of mental health service delivery organisations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 1998 | ||

| Level 1 | Appointment of person to represent the interests of mental health consumers and carers on organisation management committee, orspecific mental health consumer/carer advisory group established to advise on all aspects of service delivery | 17% | 45% |

| Level 2 | Specific mental health consumer/carer advisory group established to advise onsomeaspects of service delivery | 16% | 16% |

| Level 3 | Mental health consumers/carers invited to participate on broadly based committees | 20% | 13% |

| Level 4 | Other arrangements/no arrangements | 47% | 26% |

At a national level, the Mental Health Council of Australia was established in November 1997 as a focal national body representing all components of the mental health sector (consumers, carers, NGOs, clinicians and community groups with a substantial interest in the mental health area). The Council's role includes providing advice to governments, representing the interests of its constituency in the public domain, monitoring and analysing national mental health policy, resource allocation and outcomes and facilitating strong relationships within the mental health sector.

Despite the change in service mix and the expansion of resources allocated to mental health services, consumers still reported being marginalised and discriminated against when it came to a range of mental health, health and other social services (Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services, 1997). There was only limited acceptance in the mainstream disability services of psychiatric disability, with some difficulty in accommodating the episodic disability that is common in mental disorder. Consumers also reported that the attitudes held by those professionals were discriminatory and they were not treated as partners in the management of their condition. Local administrators and professionals resisted their participation in service planning and delivery. The involvement, which had been mandated in the Strategy, was often achieved by tokenistic practices. Furthermore, the training and support needed for consumers and carers to participate legitimately and effectively and to manage their own advocacy were underestimated. Clearly, it is easier to change structures and increase funding than it is to change the values and attitudes entrenched in health professionals.

Mental health legislative reform

Mental health legislation is the responsibility of state and territory governments, therefore eight Mental Health Acts exist in Australia. To raise and standardise the rights of consumers and the community under these Acts, the Strategy turned to Australia's commitment to the United Nations Resolution on the Rights of People with Mental Illness and the Improvement of Mental Health Care (United Nations, 1991). This became a benchmark for state and territory legislation. A Rights Analysis Instrument was developed by the Federal Attorney-General's Department to assess compliance of state and territory mental health legislation with the United Nations principles (Commonwealth Department of Health and Aged Care, 2000b ). All states and territories had their legislation reviewed, using this instrument, by a national Legislation Action Advisory Group. Recommendations resulted in new or amended legislation. During the Strategy, over half of the states passed new legislation or amended their Acts. All remaining states have new bills or amendments drafted.

Other initiatives to improve outcomes and quality

Few data were available on changes in service quality. A number of initiatives were, however, introduced in the National Plan to improve outcomes and enhance quality. These included the introduction of national mental health service standards (Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services, 1996a ), which were adopted by the national accreditation agencies.

To move beyond service activity data (such as occupied bed days or occasions of service) to outcomes required the introduction, nationally, of consumer outcome measures into routine clinical practice. A review of all available measures in the literature was undertaken (Reference Andrews, Peters and TeesonAndrews et al, 1994) and six adult measures were tested in a range of public and private hospital and community settings (Reference Stedman, Yellowlees and MellsopStedman et al, 1997). The Health of the Nation Outcome Scales and the Life Skills Profile or Mental Health Inventory (Reference Stedman, Yellowlees and MellsopStedman et al, 1997) are now being adopted in public services and private hospitals across Australia. The development of routine outcome measures for child and adolescent services also commenced (Reference Bickman, Nurcombe and TownsendBickmanet al, 1999).

DISCUSSION

There are many factors that contributed to the success and shortcomings of the Strategy. Several of these are instructive for governments undertaking mental health reform. The magnitude of the overall financial outlay in mental health was not recognised in Australia until the late 1980s. The Federal government's original reluctance to become involved in funding what are state-run mental health services dissolved when it realised that its financial contribution to income support, disability services, vocational rehabilitation and the Medicare Benefits Schedule was greater than all state and territory spending on mental health services (Reference WhitefordWhiteford, 2001). The Federal government also saw a strategic opportunity in the Strategy to limit cost shifting between itself and state governments and to integrate the hospital, community and rehabilitation components of mental health care (Reference WhitefordWhiteford, 1994).

Ensuring a stable financial base

Strategy funding was provided in the Federal/State Healthcare Agreements, the mechanism by which the Federal goverment allocates its share of funding for the state-managed public hospital system. Mental health had never been part of these Agreements but was included as a special schedule in the 1993-1998 Agreement. The Federal government inserted a ‘maintenance of effort’ clause in all Agreements, which required the Federal funding not be used to substitute for state funding but for bilaterally agreed reform activities, and for all resources released through the institutional downsizing to be re-invested in replacement services. To ensure public accountability, the annual National Mental Health Reports monitored adherence to these undertakings. The additional Federal funding served as essential ‘bridging’ funding for many of the states to undertake the development of community services before hospital beds were closed. The political profile given by the Strategy also stimulated growth in state and territory investment in mental health care. For every Federal dollar allocated under the Strategy, the states and territories added an additional AU$2.70.

Bipartisan political support

The political support of the Federal Minister for Health in 1992 was key to the adoption of the National Policy and Plan. However, mental health reform across a nation takes time, often beyond the life of an elected government. During the 5 years of the National Plan, the political party in power changed in the Federal government and in all states and territories except the Northern Territory. However, incoming Federal and state governments were required to honour the agreements signed by the previous government and the extra Federal funding was badly needed by the states. This meant that implementation was undertaken by both major political parties. Also, at the time of drafting the National Policy and Plan, a broad consensus had been reached in Australia about the directions for reform.

This consensus made it possible to develop a public position that had the support of key stakeholders, such as mental health professionals and consumer/carer groups. The impetus given to consumer/carer advocacy under the Strategy made these groups stronger and their commitment added powerful community impetus to the reform and helped to ensure bipartisan political support.

A limited focus and information base

The Strategy was criticised as being narrow in its implementation with an initial focus on serious mental illness. Although the need to provide for the most ill and disabled is critical, this focus was seen to raise the threshold for access to services and militated against early intervention. Attempts were made to remedy this late in the Strategy, with support for a range of early intervention initiatives (Reference Singh and McGorrySingh & McGorry, 1998), and the Second National Mental Health Plan explicitly identifies that access should be based on need and not diagnosis.

The National Policy was formulated without national data on population-level morbidity, disability and service utilisation. It was not until 1997 that this information was gathered through a survey of 10 600 households using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (World Health Organization, 1990) and specially designed instruments for assessing disability and service use. Of the total population, in a 12-month period, 18% were found to meet the criteria for mental disorders that were shown to cause a considerable number of ‘days out of role’. Only 38% of those meeting the criteria for a mental disorder received treatment from a health professional, with 75% of those who did receive care accessing this from general practitioners (Reference Henderson, Andrews and HallHenderson et al, 2000). Two further epidemiological surveys of the low-prevalence psychotic disorders (Reference Jablensky, McGrath and HerrmanJablensky et al, 2000) and child and adolescent disorders (Reference Sawyer, Kosky and GractzSawyer et al, 2000) found deficiencies in care. It was therefore only late in the 5-year National Plan that attention began to be paid to primary health services and child and adolescent services. Other areas, notably psychogeriatric and forensic services, received little substantial attention.

Little attention also was given to the private sector until late in the National Plan. This resulted in many private psychiatrists, general practitioners and private hospitals being excluded. Partially in response to this, the Australian Medical Association and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists established a Strategic Planning Group for Private Psychiatric Services, which now has become the vehicle to coordinate private sector reform. Over time, the work of the Group was aligned with the programme of the National Strategy. Initiatives also were launched to address primary care services, especially those provided by general practitioners (Joint Consultative Committee in Psychiatry, 1997). Another outcome of the marginalisation of the private sector has been the much slower involvement of consumers in decision-making in this sector (Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services, 1996b ).

Renewal of the National Mental Health Strategy

The evaluation of the Strategy concluded that significant gains had been made in mental health reform. However, it also concluded that reform had been uneven across and within jurisdictions, and that further action was required to maintain and build on the momentum generated under the Strategy. The final report (Commonwealth Department of Health and Family Services, 1997) identified 14 priority areas for future mental health reform activity, including a greater focus on quality and outcomes, extending the role of consumers and carers, more attention to private sector reform and addressing population approaches to prevention and promotion.

Based on the successful model of the Strategy for achieving reform, but acknowledging the unfinished agenda, a second 5-year National Mental Health Plan (1998-2003) was endorsed by all Federal, state and territory governments (Australian Health Ministers, 1998). The priority areas for the Second Plan are those identified in the evaluation (Reference WhitefordWhiteford, 1998).

Overall, 5 years was insufficient time to achieve the optimistic goals that the Strategy had set itself. The renewal for a further 5 years is an acknowledgment of the work still needed, an endorsement of the achievements to date and an expectation by government and the community that additional improvements in mental health services in Australia will be forthcoming.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

• Sustained national mental health reform is achievable.

-

• Structural reform of mental health services is easier to achieve than improvements in service quality.

-

• The support of clinicians, consumers and carers is a critical factor in the success of mental health reform.

LIMITATIONS

-

• The reform of mental health services in Australia did not include the collection of quantitative data on outcomes for consumers.

-

• Few data were available on primary mental health care, where most patients with mental disorder in Australia receive treatment.

-

• The consistency and reliability of data collected by states and territories were not subject to independent audit.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.