William Cecil’s interests in heraldry and genealogy, and his particular concern for the antiquity of his own pedigree, are well known. Stephen Alford calls him ‘a keen, if a too creative, genealogist’ and A L Rowse notes that ‘Drawing up pedigrees was to Lord Burghley what Anglo-Saxon antiquities were to Archbishop Parker – a refuge from the crosses of this world’.Footnote 1

In many ways, Cecil reflected the concern for an ancient lineage and the fashion for genealogical research that swept the gentry of the sixteenth century, as great families, both the well-established and the newly elevated, sought to solidify their positions with antiquarian research.Footnote 2 The search for ancient and notable family origins recognised that, while some contemporary theorists argued that virtue was the source of gentility, others (such as the heraldic writer Gerard Legh) continued to claim that an uninterrupted line of gentle descent was necessary for anyone who wished to be viewed as ‘a gentleman of auncestrie’.Footnote 3 William Cecil’s personal papers, now held at Hatfield House, are full of pedigrees and genealogies, many either written or annotated with Cecil’s distinctive hand. These documents, some of which trace his ancestry back as many as sixteen generations, range in quality from rough notes to a beautiful pedigree roll. Cecil’s antiquarian interests were widely known in his own day, and Oswald Barron suggests that early heraldic writers like Legh or John Bossewell might include the details of Cecil’s pedigree ‘in high hopes of catching the patron’s eye’.Footnote 4 Barron thus imagines heraldic writers in control of their works, while Cecil passively consumed their books as he pursued (or took refuge in) his private pastime. Cecil, however, was an active promoter of his pedigree and he worked to make his ancestry known. To achieve this end, his private papers were made available to authors and publishers so that his genealogy could reach as wide an audience as possible.

The first episode of the Cecil family history to move from private papers to public record tells a fictitious story in which John Sitsilt defends his claim to his ancestral arms against William Fakneham at the battle of Halidon Hill in 1333.Footnote 5 This story enters the second edition of Legh’s Accedens of Armory in a rushed, haphazard manner,Footnote 6 but later interventions were more deliberate and included more elaborate genealogies. The Sitsilt story affirmed the antiquity of Cecil’s family and arms and thus solidified his position among gentlemen. Cecil’s desire to place the story in print highlights the fact that an imagined genealogy was only useful if it was known. A typical family might display its coat of arms in architecture or glass, sometimes altering medieval monuments to do so. Genealogical rolls might also be commissioned to convert family lore into displayable text.Footnote 7 Such manipulations of the past, by their physical nature, were often localised, being limited to an ancestral chapel, the family house or even a private chamber. The limited audience for such displays might have been sufficient for a provincial gentleman, but William Cecil’s position provided him with a wide variety of means to ensure his ancient lineage was known throughout England. Cecil’s repeated attempts to promulgate the story of his own ancestry show that Barron’s characterisation of printers and heraldic writers trying to catch Cecil’s eye is completely backward. Rather than using genealogical study as a refuge from the world, Cecil appears to have viewed his research as another avenue by which he might advance his position in Elizabethan society, and he sought out printers, officers of arms and craftsmen to publicise his arms and pedigree. Cecil’s prominence, and the survival of his personal papers, provides a rare opportunity to trace the ways that spurious genealogies could be moved from the private study to the public record.

William Cecil (1520–98) was from a relatively humble background but became one of the most powerful men in Elizabethan England. After an education at Cambridge and Gray’s Inn, Cecil first joined the service of the Duke of Somerset and then that of the Duke of Northumberland. He carefully navigated his own path through the successions of Lady Jane Gray and Queen Mary before being named Secretary of State by Elizabeth (1558). In February 1571 he was elevated to the title Lord Burghley and in 1572 he was named Lord High Treasurer. Cecil’s influence over all aspects of Elizabethan government was immense.

There is little documentary support for any account of William Cecil’s ancestors beyond his grandfather.Footnote 8 Cecil made several different claims to antiquity,Footnote 9 but he settled on a story of Welsh origins in the 1560s when he developed a friendship with Edward Stradling of St Donat’s castle in Glamorgan. Stradling’s own historical research was well known, and his library was ‘the envy and quarry of many a gentleman and antiquarian in England’.Footnote 10 In the 1560s Stradling and Cecil shared correspondence about their pedigrees and Stradling’s heroic tale of ‘The Winning of the Lordship of Glamorgan out of the Welshmen’s hands’.Footnote 11 Eventually, the Cecil genealogy would associate his family with Stradling’s narrative, but the first public reference to Cecil’s Welsh ancestors does not actually mention Cecil by name and only tells the story of the defence of the Sitsilt arms at the battle of Halidon Hill.

The dramatic story, in which John Sitsilt defends his ancestral arms and they are eventually confirmed by Edward iii, first appears publicly 1568, in the second edition of Gerard Legh’s Accedens of Armory. The Accedens was first published in 1562, but the earlier edition does not mention either Cecil or his ancestors. This is actually rather odd, since despite his relatively humble position as a London draper, Legh’s heraldic interests and his association with the Inner Temple put him in close contact with some of the most powerful men of Elizabethan England. Legh knew Cecil personally and they shared an interest in coats of arms, as is clear from Legh’s will:

Item, I gyve vnto my cossen Sir Wyllyam Cecell one Boke of all the Armes of sutche knightes as weare made by that worthye kynge Edwarde the Fyrste of Englande syns the conquest, the whytche boke he borrowed of me, as apeareth by hys letter.Footnote 12

Unfortunately, Cecil’s letter does not survive, but the book Legh mentions may have been a copy of the Falkirk Roll, the incipit of which echoes Legh’s description: ‘Ceux sount lez grauntz seigneurs a banniere quelx le Roy Edward le premier puis le Conquest avoit par devers Escoce.’Footnote 13

The Accedens is in the form of a colloquy between characters named Gerard (a herald and teacher) and Legh (a student). In the first edition, as part of a discussion on the terms for multiple lions, the teacher tests his student by asking him to blazon a complex coat of arms:

[Gerard]: In some cotes, there be many lions, wherunto apperteineth a rule. If there be mo then one of them in one scocheon, they shall ende in this worde ‘-seux’; that is to saye, ‘lyonseux’ and ‘heronseux.’ And nowe that you haue well learned, I will appose you whether you can tell me this cote [fig 1].

Fig 1. Sample arms in Legh Reference Legh1562, fol 85r. Author’s copy.

Legh: I will.

Gerard: Say on.

Legh: He beareth of ten clossetts, Argent & Azure, vpon fiue escocheons Sable lionseux rampand Argent.

Gerard: You haue done but pretely well, for this is the proper blazonne: He beareth x barrulettes, Argent and Azure, on v. escochons Sable lions rampand of þe first, ii, ii, and, i. You shal vnderstand, theis are no ‘lionseux’, because they stande on sondry escocheons, but if the scocheons were not there, they not being parted with any of the ix honorable ordenaries, then sholde they be lionseux. A cote borne in this sort is called a quadrate royall.Footnote 14

Legh often uses the arms of his contemporaries as examples, presumably to flatter his friends and associates, and it might be argued that Legh intends to allude to Cecil. The arms here, both blazoned and in trick in the woodcut, are a slight variant of those attributed to Sitsilt in a sixteenth-century addition to the Ashmolean Roll, where they differ slightly by having six escutcheons and lions: ‘Monseur de Sitsilt barre de diz peces argent & asur vi escocheons argent de tant diz lyons sable.’Footnote 15 The Sitsilt arms, however, are the fourth in a list of twenty-four arms that have been added to the roll and it is quite likely that these additions were made after the arms had already become associated with Cecil.Footnote 16 Robert Glover copied the Ashmolean Roll in about 1575 and did not include the twenty-four-name addendum, the Dictionary of British Arms lists no other medieval reference to the Sitsilt arms, and I know of no reference to the arms that can be dated before they appear in Legh’s first edition.Footnote 17 The complex arms, which are more typical of sixteenth-century design than fourteenth, may have been invented by Legh simply to illustrate his point about the blazon of lions that ‘stande on sondry escocheons’ and to provide a good test-case for Gerard’s trick question. It is likely, in other words, that the arms were not associated with Cecil at all in 1562 and that they were adapted and adopted by Cecil after he saw them in Legh’s book.

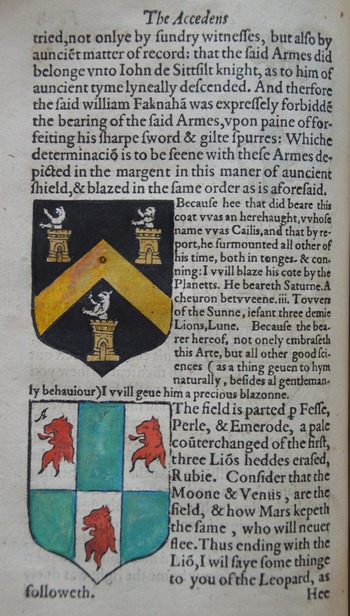

Fig 2. Sitsilt arms in Legh Reference Legh1568, fol 49r. Author’s copy.

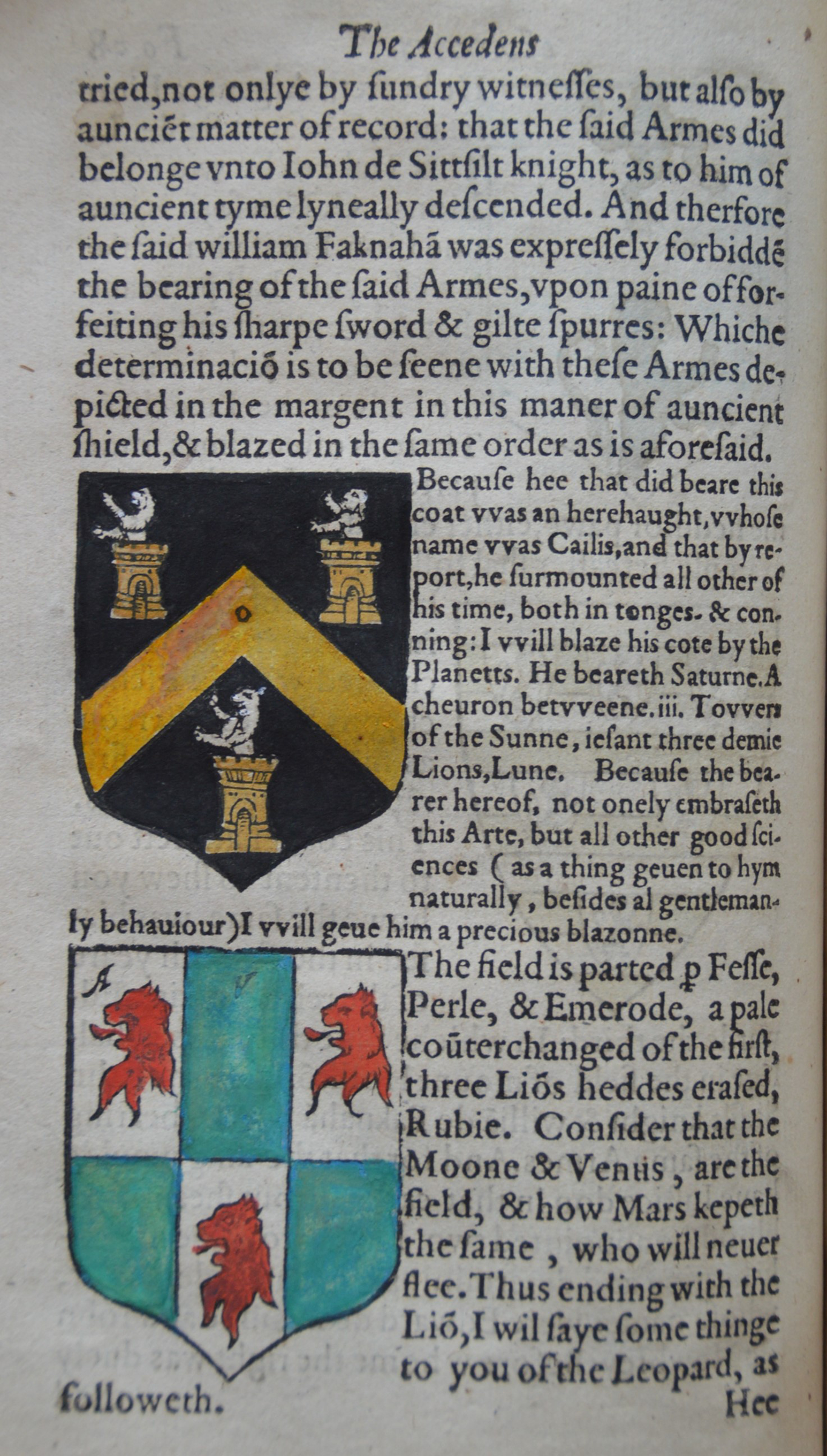

Legh died in 1563, shortly after the publication of the first edition of his book. The Accedens, however, was reprinted three more times by Richard Tottell, then twice more by other printers.Footnote 18 There are numerous variations, both large and small, throughout subsequent editions, but the changes to the passage describing lions set in individual escutcheons are of particular importance to William Cecil and the dissemination of his narrative of ancient ancestry. The second edition of the Accedens, printed in 1568, eliminates the discussion of multiple lions and the invented test in blazon. Instead, this edition simply includes a revised woodcut and blazon before it offers a new passage that describes a supposed dispute over the arms. In place of what is quoted above, the 1568 edition (and all subsequent editions) reads (fig 2 ):

[Gerard]: He bereth of tenne baruley, Argent & Azure, charged with six eschocheons sables, thereon as many lions of the first rampand langued Geuls.

This cote I haue sett out to th’entent to shew you howe the same was blased in the seuenth yeare of the reigne of King Edwarde the Third, in whiche time there was a challenge in the field of Mount Holliton betwene Iohn Sitsilt, knight, & William de Faknaham for the bearing of the same armes. And for that the king woulde haue iustice don in that case without sheading of blood, he appointed two iudges to haue the only hearing and determininge of the saide matter, whose names were Edward de Beaulile and Iohn de Mowbrey. Before whome the right was duely tried, not onlye by sundry witnesses but also by auncient matter of record, that the said armes did belonge vnto Iohn de Sittsilt, knight, as to him of auncient tyme lyneally descended. And therfore the said William Faknaham was expressely forbidden the bearing of the said armes, vpon paine of forfeiting his sharpe sword & gilte spurres. Whiche determinacion is to be seene, with these armes depicted in the margent in this maner of auncient shield, & blazed in the same order as is aforesaid.Footnote 19

Fig 3. Typographical changes in Legh Reference Legh1568, fol 49v. Author’s copy.

This remarkable story is anachronistic fiction. The hereditary and proprietary nature of arms developed over the fourteenth century and the first recorded dispute over arms was argued at the siege of Calais sometime between 1345 and 1348.Footnote 20 Pushing such cases into the 1330s would predate any other dispute by a generation. More immediately, however, the story establishes John Sitsilt as an illustrious and chivalric figure whose defence of his family’s honour was recognised by no less august a figure than King Edward iii. Sitsilt’s heirs (and we will see that Cecil claimed to be such an heir) would share in this chivalric honour.

The precise means by which this story was inserted into The Accedens of Armory is unclear, but it seems likely that Cecil himself had a hand in influencing the printer Richard Tottell.Footnote 21 The evidence from the physical book indicates that the decision to add the Sitsilt passage was made late in production. Immediately following this altered passage, the Accedens describes the arms of a herald named ‘Callis’ (‘Cailis’ in the 1568 edition) and the arms of Richard Argall. As Godfrey notes,

No reference to a ‘herald’ of this name has been found, nor is there any Calais pursuivant known to have borne [the arms illustrated], but Gerard Legh’s mother was Isabel Cailis and these arms were in St Dunstan’s in the West on the brass to Gerard’s father, Henry Legh (d. 1568). Is it possible that the surname comes from an ancestor who was Calais pursuivant?Footnote 22

Richard Argall was Legh’s friend and wrote the dedicatory epistle to the volume.Footnote 23 Apart from naming the bearer of the arms, there is nothing odd about these passages in the first edition, but beginning with the 1568 edition, and in the next three editions, the text beside the arms of ‘Cailis’ is set in smaller type. Nichols noted the typographical oddity and suggested that Legh, while discussing family members and friends, had the passage set more densely, either ‘from mock-modesty, or possibly to attract attention’.Footnote 24 Such a reading is untenable, however, as Legh had died five years earlier. The change in font size is a typographical decision, unaffected by authorial intent. In fact, it was the addition of the Sitsilt passage that necessitated the smaller type in the Cailis and Argall passages.

The smaller type of the 1568 edition is found on the verso of the final leaf in a quire (sig. G.8v, fol 49v; see fig 3). The typical page of the 1568 edition contains thirty-two lines of text, but, because of the smaller type, folio 49v contains thirty-six lines of text, or four additional lines. Folio 49r, which contains the Sitsilt addition, has been set to include thirty-three lines, or one more line than normal. Folio 49 (recto and verso) therefore has five extra lines in total. In addition, the fifteen lines of smaller type allow for more characters per line than is typical of the volume. The space created by these five extra lines of text has been filled with the expanded Sitsilt story, which is fifty-three words longer than the text it replaced. Or, to put that another way, the expanded Sitsilt story has forced the compositor to create space for fifty-three additional words of text. That this space was created on the last leaf of a quire implies that this solution was necessary because the text of the following quire (ie quire H) had already been set in form. Spreading the extra lines across several leaves simply by adding one line to several pages (as was done on 49r) might have looked better, but would have caused additional work in the shop; at least five folios (49r to 51r) would have needed to be reset. The existing solution, haphazard as it is, requires the least amount of resetting of type. Even so, mistakes were made: the folio is numbered ‘58’ rather than ‘49’, perhaps indicating haste. The three subsequent editions, which are all set from their immediate predecessor, copy the typography line-for-line and thus reproduce the smaller type. Only in the sixth and final edition of 1612, which is reset from scratch, does the change in font size disappear.

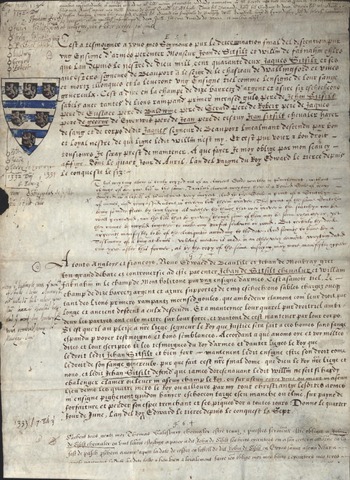

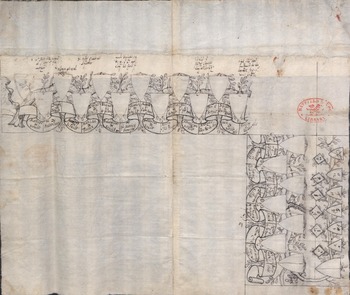

I propose that this last-minute change, made while the second edition was in an advanced state of completion at the press, results from the influence of William Cecil himself. Cecil obviously stood to gain from a story that promoted his ancestral honour, especially in 1568, two years before he was elevated to the title Lord Burghley. Cecil was also associated with Legh: recall that he would have come into ownership of the book of arms he had borrowed from Legh after the death of the author. Beyond that book, Cecil’s interest in heraldry and genealogy is specifically intertwined with Legh; he owned a copy of Richard Strangeways’s manuscript, which was itself used extensively by Legh as a source.Footnote 25 Cecil also owned a manuscript copy of Legh’s Accedens; although it is transcribed from either the 1591 or 1597 edition,Footnote 26 it does show Cecil’s interest in the work. Most significantly, however, Cecil owned and annotated copies of the Sitsilt text that was used as a source in the Tottell print shop. The somewhat obscure citation at the end of the Accedens passage provides a clue about its origins: ‘Whiche determinacion is to be seene, with these armes depicted in the margent in this maner of auncient shield, & blazed in the same order as is aforesaid.’ This passage refers to a document currently among the Cecil Papers in Hatfield House.Footnote 27 Now two leaves of parchment, but at some point a short roll of at least three membranes, the document contains several different texts related to the Sitsilts in the time of Edward iii. The verso (or dorse) is blank apart from some mathematical calculations (on which more later), a genealogical sketch of the Sitsilts by Cecil himself and the caption ‘The Copy of twoo auncient wrytyngs made in þe 6 and 7 yeres of Kyng Edward 3’, also probably by Cecil.Footnote 28 The position of this caption, framed by a typical set of creases, indicates that what is now the first leaf was folded before it was integrated into a roll. The recto of the first leaf is dominated by the two texts mentioned in the caption (fig 4). They are visually centred on the leaf and written in larger characters than the other texts. In the upper left-hand margin, as the Accedens promised, can be seen the Cecil/Sitsilt coat of arms, drawn on an ancient shield similar in shape to that in the Accedens woodcut of 1568. Above and below the shield Cecil has sketched a rough pedigree of the Sitsilts (with details taken from the first text). At the top and bottom of the leaf, in a smaller hand, are fragments of Latin and French texts that discuss financial relationships between ‘John de Sitsilt, cheualer’ and various other figures. These, which continue onto the second leaf, give the whole a sense of having once been part of a larger collection. The second leaf also contains several short charters and deeds, one of which is fitted between texts that were written earlier, and a pedigree of the Baldwin family showing their relationship to the Sitsilts. This second leaf was never folded, but has the creases typical of a roll.

Fig 4. Records of a challenge of arms, CP vol 218/3, fol 1r. Reproduced with permission of the Marquess of Salisbury, Hatfield House.

The two French texts that dominate the first folio describe the dispute of arms at Halidon Hill. The first text, with the incipit ‘Cest a tesmoigner’, describes itself as ‘le determination final’ in a dispute between John Sitsilt and William Fakneham. The determination rests on the fact that in 1142 James Sitsilt was killed at the castle of Wallingford while bearing the arms in question (‘Cest a dire, en la champe de dize barretz d’argent et asure, siz eschocheons Sabels, auec tantes de lions rampand primer incensed guls’). The text then lists a direct line of descent through ten generations from the ‘Jaques’ (ie James) at Wallingford to the ‘Jean’ at Halidon Hill. There is no authorial name attached to the document, but it would seem to be a statement produced by an authority on heraldic practice, possibly a king of arms.

The second text, with the incipit ‘A touts Angloys’, claims to be a formal decision written by Edward de Beaulile and John de Mowbray. This introduces the debate over arms (here said to have ‘cinq eschocheons Sables’) and places the event clearly at Halidon Hill. The disputants, it claims, were about to put their bodies at risk in defence of their claims, but the king intervened and demanded that a decision be reached peaceably. Texts were sought after, as was ‘les tesmoignes du roy d’armes et dauter lieges le roy’ (the testimonies of the king of arms and other servants of the king), and it was decided that John Sitsilt should continue to bear the arms and that William Fakneham must cease to bear them or face dishonour. The texts are dated, as the caption stated, the sixth and seventh years of the reign of Edward iii.

Between these two texts, written in a different hand, is a brief account in English of the provenance of the documents, claiming that they are ‘truly copyed out of an ancient deede written in parchement, without change of any one lettre in the same’. The note claims that a round seal was attached to ‘Cest a tesmoigner’, but it was pressed flat and hence unreadable. Despite this loss, ‘certenly the deede appeerith manifestly to be of the antiquitee according to the date. And seemith to haue ben a testimony of a king at armes’.Footnote 29

As with Tottell’s account of this dispute in the 1568 Accedens, the anachronism of this testimonial is obvious. Kings of arms did not participate in disputes over cote armure before the fifteenth century, and the French of the passages shows no signs of having been copied from an Anglo-Norman original. It is, rather, the largely case-free French of the mid-sixteenth century.

The document is undated. The mathematical notes on the dorse of the first leaf seem to calculate the time since the events being described (ie the reign of Stephen and the battle of Halidon Hill; both dates are in Cecil’s notes in the margin):

1570 1570

1142 1332

0428 0238

There is, however, no indication that these calculations were completed when the document was made. Given that 1570 is a significant date for Cecil – in January of this year (by contemporary dating) he was elevated to the title Lord Burghley – these calculations may have been added to the document to show the time it took the family to attain nobility after gaining and defending their arms. It is, of course, possible that the simple equations were performed when the document was created. If that were the case, the document would be a copy of an earlier text originally used by Tottell as he revised Legh’s Accedens in 1568. Given the patch-work nature of the leaves – the multiple hands, the different patterns of creases on different leaves, the obvious attempts to fit additional texts around existing texts – it is more likely, however, that the document is the first copy of this particular assortment of texts, and thus the original source document for the Sitsilt story in the 1568 edition of Legh’s Accedens.Footnote 30

Indeed, the English text in the Accedens summarises much of ‘A touts Angloys’, the second text in Cecil’s collection. The parallels are often so close as to be translations. Both texts claim that there ‘there was a challenge in the field of Mount Holliton betwene Iohn Sitsilt, knight, & William de Faknaham’ or a ‘grand debate & controuersie ad esté par enter Iehan de Sitsilt cheualier, et Willam Faknaham, in le champ de Mont holitone’; both assert ‘that the king woulde haue iustice don in that case without sheading of blood’ or ‘que il au pleise a nostre liege segneur le Roy que Iustice sera fait a ces homes sans sange espandu’. The names of the judges are given, although at different points in the narrative – the English in the middle, the French at the beginning – but in both instances it is decided ‘that the said armes did belonge vnto Iohn de Sittsilt, knight, as to him of auncient tyme lyneally descended’ or ‘que le droit le dit Iehan Sitsilt et bien fort mantenent le dit ensigne estre son droit, come le droit de son sange genereulx’. The French has a more detailed account of the restrictions placed upon William Fakneham, but both agree that he ‘was expressely forbidden the bearing of the said armes, vpon paine of forfeiting his sharpe sword & gilte spurres’ or ‘sur payne de forfaiture, & perder son espeé trenchant, & ses piques dor’.Footnote 31

Despite the English note claiming that these documents are copies of older, authentic records with conveniently obscure yet authoritative seals, there are no earlier records to support the story. We can, however, reconstruct its first appearance in print. In 1562 Gerard Legh completed The Accedens of Armory, for which he invented an elaborate coat of arms to illustrate the use of the suffix ‘-seux’ when blazoning multiple lions. Legh died shortly thereafter, but his printer, Richard Tottell, began the production of a second edition in 1568. Cecil, having seen the arms in Legh’s book, approached Tottell late in production with a document that outlined his ancient claim to the arms (now with six escutcheons) and their recognition by Edward iii. Tottell, not surprisingly, agreed with Cecil, and made the last-minute alterations to his woodcuts and text to please the queen’s councillor. Given the limitations of space, Cecil’s document was translated and edited to require as little additional work as possible in the composing room, but that work did leave a trace in the typographical oddities of the folio on which it was printed.

Cecil’s interest in promoting the story of his arms and their defence did not end there. Four years later, in 1572, Richard Tottell was again producing a heraldic treatise, this one by John Bossewell. Bossewell’s Workes of Armorie, like Legh’s Accedens, is a large treatise on heraldic practice that combines technical details on blazon with discussions of chivalry and nobility. Bossewell knew Legh’s Accedens well; he borrows from it often and cites it favourably. Also a product of Tottell’s shop, Bossewell’s book is illustrated with several woodcuts that were originally used in Legh’s text. After briefly outlining a conflict of arms between John Chandos and the Lord of Claremont at Poitiers, Bossewell also includes the story of the Sitsilt dispute:

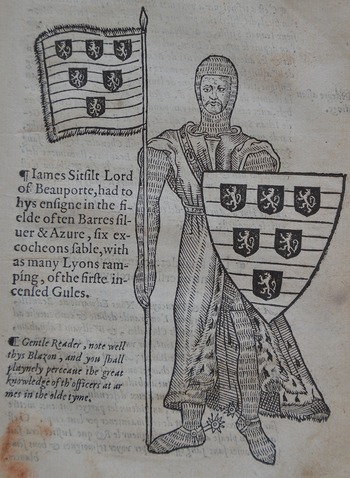

Suche lyke controuersie dyd chaunce, betwene two valiaunt, knyghtes, Sir Iohn of Sitsilt, and Sir Willyam of Facknaham, for raysinge in fielde the cote armoure, here after the antique maner displayed. But the ryghte of the bearing thereof (which they were readie to trie by force of armes) was adiudged to Sir Iohn Sitsilt, as to him moste ryghtefully and lyneally descended by good & lawfull byrthe, as heyre of bloode and of bodie of Iames Sitsilt, Lorde of Beauporte. For the truthe whereof (gentle reader) here ensueth verbatim the copye of the very originall wrytinges, in hæc verba:Footnote 32

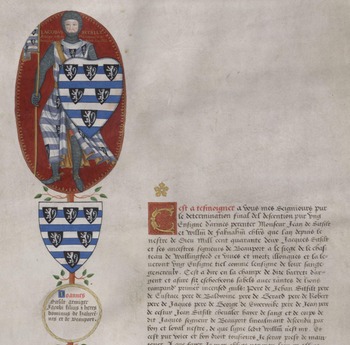

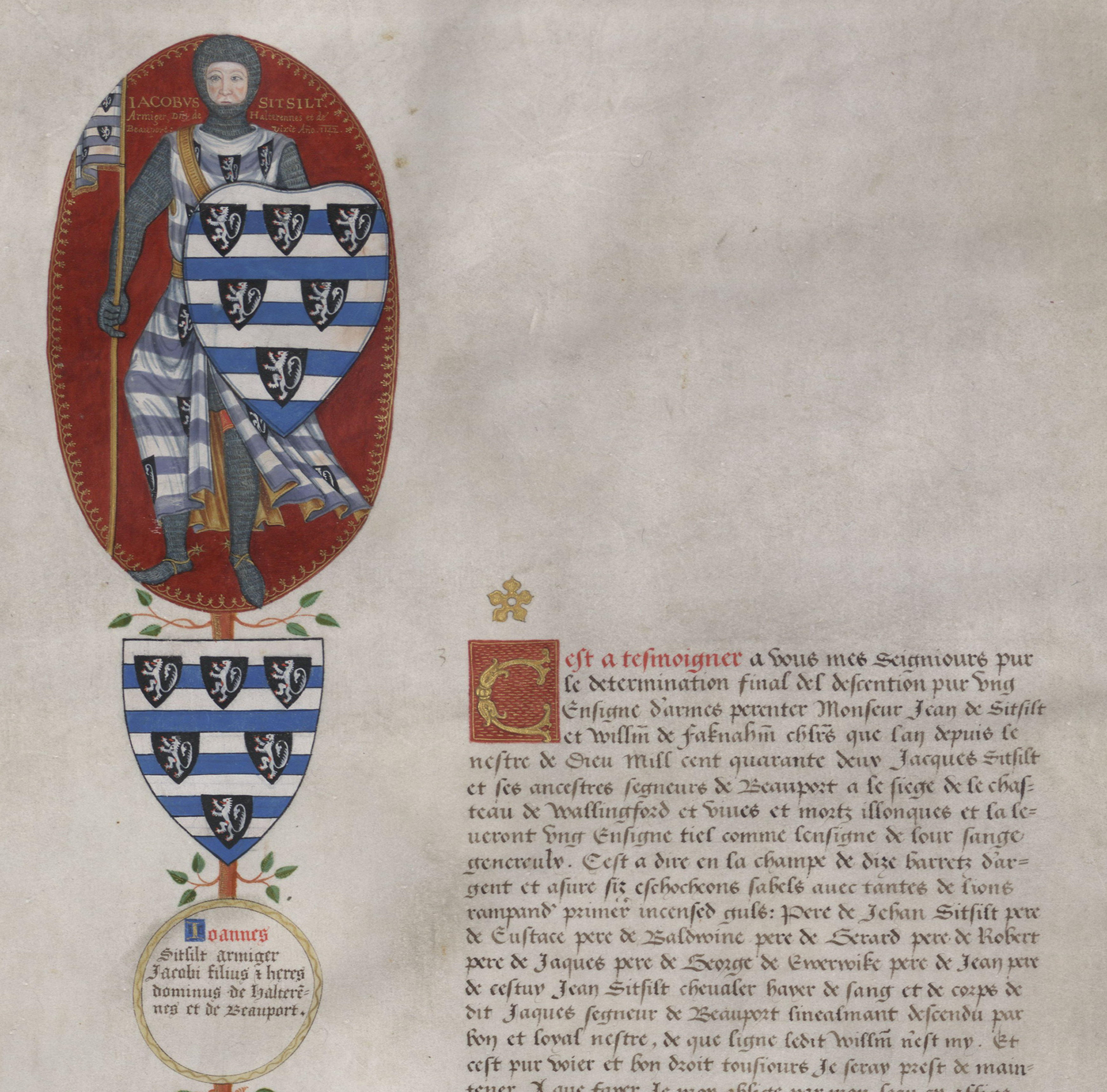

This is followed by a full-page woodcut of James Sitsilt (who died at Wallingford) in mail holding a banner and shield, both of which bear the arms in question. The accompanying blazon cites the ‘great knowledge’ of ancient officers of arms (fig 5).Footnote 33 The promised ‘wrytinges’ follow on the verso, and they include both ‘Cest a tesmoigner’ and ‘A touts Angloys’ from the Cecil document described above. There are accidental variations in spelling, but only two substantial variations: in the first text Bossewell blazons the lions as ‘incensed Gule’ (ie with red tongues), but the Cecil manuscript more correctly blazons them ‘incensed Guls’. Bossewell also has a typical typographical error, saying that Fakneham risked losing ‘son espeé trenchaut’ rather than ‘trenchant’, as in the Cecil manuscript.

Fig 5. Sir James Sitsilt, in Bossewell Reference Bossewell1572, fol 80r. Author’s copy.

Bossewell does not include the lengthy English note describing the provenance of the documents. Instead, he inserts a caption between the two texts, indicating that the second is ‘The final determinacion of the controuersie aforesayde’. Cecil’s interest in authorising citations is not lost entirely, however. Following the French texts, Bossewell includes his own citation, which echoes much of the language from the Cecil manuscript:

The whych sayde originall writinges, beyng written in parchement, accordyng to the antiquitie of the tyme, I my selfe haue seene being in the possession of the ryghte honorable the Lorde of Burghley, to whome in blood the same belongeth, whose name beinge written at thys daye Cecill is neuertheles in Wales, both in speche and common writing, vsed to be vttered Sitsilt or Sitsild, where the originall house at thys daye remayneth nere Aburgenny.Footnote 34

Writing four years after the 1568 edition of the Accedens, Bossewell has integrated the episode into his text more seamlessly than it entered Legh’s book. Bossewell also makes explicit, in a way the Accedens did not, that these arms continued to be borne by Cecil, the current lineal descendant of James Sitsilt. Bossewell, who dedicates the Workes to Cecil, is thus able to flatter his patron by including not only the arms, but the narrative of their defence. But Bossewell also makes clear that Cecil’s patronage included providing the documents from which the story was copied. In 1572, Cecil (now Lord Burghley) was once again able to ensure that Tottell’s print shop helped disseminate the story of his ancient claim to arms. As both works were reprinted (Legh’s Accedens in 1576, 1591, 1597 and 1612; Bossewell’s Workes in 1597), this story reached an ever wider audience.

Richard Tottell’s print shop provided a public venue through which Cecil was able to reproduce and disseminate his private manuscripts. He also reproduced and disseminated the texts in his own home. The texts in CP vol 218/3 reappear in a more formal collection, CP vol 266. This collection of texts, all but one in the same hand, argues for the antiquity of the Cecil family. The collection opens with a genealogy in English that begins in the reign of William Rufus:

In the yere of Christ 1091 Robert Sitsilt came with Robert Fitz Hamond to the conquest of the countrie of Glamorgan and after wedded a ladye by whome he had Haulterennes and other landes in Herefordshire and Glostershire. He had a sonne called James Sitsilt that was slayne at the siege of Wallingford in the raigne of Kinge Stephen, who as the cronacle of the Abby of Dore saith at the same tyme had on him a vesture whereon was wrought in nedle worke his armes as they be made on the tombe of Gerold Sitsilt in the Abby of Dore. He had a sonne called John Sitsilt and foure daughters.Footnote 35

The other ancestors who are merely listed in ‘Cest a tesmoigner’ also appear in the genealogy, each given brief narrative form. Like other texts in the collection, the English genealogy has an introductory note, possibly in Cecil’s hand, declaring that it is ‘the true coppie word by word of an old role in parchment which semeth to haue bene written in the end of the raigne of King Edward the 4’.Footnote 36 A series of French texts follow, filling fols 4–8. These also include headings or captions, one claiming that the collection includes a ‘true copie of twoe old charters or euidences written and sealed in parchment’ which prove the veracity of the English genealogy, the other claiming to be from sources ‘all in parchment’.Footnote 37 Rather than copies of ancient parchment, most of these French texts are copied from CP vol 218/3, including the deeds, charters and the two texts on the dispute of arms.Footnote 38 The copies are substantially identical, and even the spelling is remarkably close with only five spelling variations between the two witnesses of ‘Cest a tesmoigner’ and ‘A touts Angloys’.

CP vol 266, therefore, seems to be a personal attempt to bring together a wide variety of texts that demonstrate the antiquity and nobility of the Cecil line. In addition to the English genealogy and the French documents from CP vol 218/3, other texts in English, Latin and French are included. Only one of these, a letter in French from William de Clinton, the Earl of Huntington, and Roger, Bishop of Coventry and Lychfield, mentions the dispute of arms at Halidon Hill. Although better organised than CP vol 218/3, the manuscript remains a working document. The margins of all the texts in the manuscript are annotated by Cecil with diagrammatic pedigrees tracing the main and cadet branches of his own family. Dates and summarising notes, also in Cecil’s hand, gloss many of the texts, and the headings citing ancient sources are often squeezed into the upper margins. Throughout the 1560s and 1570s, while the story of John Sitsilt’s dispute circulated in both Legh’s Accedens and Bossewell’s Workes, the full genealogy and its supporting documentation was largely confined to these documents. Cecil, however, did work to make this more detailed genealogy a matter of public record.

A year after the appearance of the 1568 edition of Legh’s Accedens, the arms of Sitsilt/Cecil and his genealogy were confirmed during the Visitation of Herefordshire carried out by Robert Cooke, Clarenceux King of Arms.Footnote 39 More ostentatiously, Cecil also made his arms and genealogy public in the decoration of his house, Theobalds. The house, which no longer stands, included a series of elaborate decorations that celebrated the antiquity and nobility of England. Cecil’s own pedigree was used to decorate the walls of the loggia, or covered veranda, that flanked the doors leading to the great garden.Footnote 40 The German traveller Paul Hentzner, who visited the estate at the time of Cecil’s funeral, commented on the genealogical decorations,Footnote 41 and the antiquarian Richard Gough (1735–1809) drew a sketch of the walls, which is preserved in Nichols’s Progresses and Processions. Although the sketch has gaps, indicating that some of the text was unreadable in the eighteenth century, the pedigree is clearly copied from the English genealogy in CP vol 266. Nichols attempted to emend the text based on later printed versions of the pedigree, but the original text on the walls of Theobalds can be more convincingly reconstructed using the text of CP vol 266 (quoted above) to fill in the blanks left by Gough and to correct his transcription errors (fig 6):Footnote 42

[In the yere of Christ 1090 Robert Sitsilt]

came with Robert Fitz Hamon

to the conqueste of þe covntrie of Gla

morgan and after wedded a lady by

whom he had [Haulterennes]Footnote 43 and

[other]Footnote 44 land on H[ereford]shire and Glo

str[es]hir[e] He has a son called James

de Sitsil[t that was slayne at the siege of

Wallingford in the raigne of kinge Stephen

who, as the c]ro[nacle of the Abby of

Dore] [saith, then]Footnote 45 had on him [a vesture

whereon was wrought in nedle worke his

armes as they be made on the] tombe [of

Gerold Sitsilt in the abby of Dore. He had a sonne

called John Sitsilt] and fowre davghter[s].

Sutton, who does not discuss Gough’s sketch, notes that such a pedigree in so conspicuous a space trumpeted ‘the ancient nobility of the Cecil family’.Footnote 46

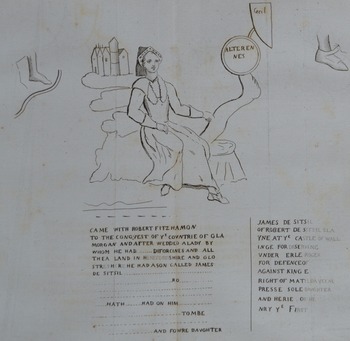

Fig 6. Richard Gough’s sketch of Theobalds genealogy in Nichols Reference Nichols1788, 7. Author’s copy.

Cecil’s ancestry was celebrated in other rooms, with one visitor describing a gallery that featured ‘portraits of the Cecil family, with an account of the notable acts of each under different reigns’.Footnote 47 Such images may have been in the form of a genealogy, but the incomplete records of the building do not specify. A sketch in the Cecil archive, however, suggests that such ornamentation was at least planned (fig 7). The sketch of decorations for two adjoining walls shows a vine, rooted on the left and growing to the right, turning a corner to a second wall halfway along. Blank shields are hung from the vine, presumably intended to show the changing arms of the Sitsilt/Cecil family. Below the arms, scroll work bears the names of Cecil’s ancestors and their wives, beginning with ‘Robert de Sitsilt’ and ending with ‘William Cecil … Dominus Burghley’ himself. At this point the vine branches to form a second layer with blank shields and lozenges hanging from it, presumably to illustrate the arms of Cecil’s male and female children.Footnote 48 The names are in several hands, including Cecil’s. Cecil has also added notes above the first range of shields, including the note above ‘Johanes de Sitsilt, milites’ that ‘This Johanes had judgment for his armes’.Footnote 49

Fig 7. Sketch of Cecil pedigree for decoration, CP vol 143/12, fol 1r. Reproduced with permission of the Marquess of Salisbury, Hatfield House.

The culmination of this genealogical programme is a formal pedigree roll of the Cecil family from James Sitsilt to William Cecil, a lavishly illustrated heraldic production. The whole was produced in 1580 by Robert Cooke and Robert Glover (Clarenceux King of Arms and Somerset Herald) who, in a formal epigraph, claim to have examined ‘cartas, euidentias cæteraque antiquitatis monumenta’ (charters, evidences and other monuments of antiquity). Similar citations in Latin precede the texts copied from CP vol 266.Footnote 50 The language is by this point familiar. It is taken from the headings of the various collections of Sitsilt documents that Cecil made available to those he enlisted to help disseminate his genealogy. Pedigree rolls had become common by the mid-sixteenth century as many families sought to promote their claims to noble lineage through heraldic display.Footnote 51 As is typical of the genre, the Cecil roll is structured around a central pedigree (the Latin text is based on the English text in CP vol 266) which is surrounded by supporting texts in both French and Latin. All the texts in the Cecil roll have been copied or adapted from the collection in CP vol 266, including both ‘Cest a tesmoigner’ and ‘A touts Angloys’ which appear at the beginning and end of the texts, framing the entire family narrative.Footnote 52 There is no description of a damaged seal authenticating the documents; instead, the letter of the Earl of Huntingdon and the Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield is included in an elaborate trompe l’oeil that illustrates their perfectly preserved seals.Footnote 53 Bossewell’s Workes of Armorie has also been used in the pedigree’s production: the illumination of ‘Iacobvs Sitsilt’ that stands at the head of the pedigree is modelled on the woodcut of the same figure in Bossewell’s works (cf figs 5 and 8). Such portraits of principal founders became fashionable by the end of the century, but Baker speculates that this ‘may have been one of Robert Glover’s inventions’ since its appearance in the Cecil roll is an early example.Footnote 54 Such influence assumes that the roll was viewed by Cecil’s contemporaries, and it is easy to image that it was displayed to the curious, either as a permanent decoration or as an object to be unrolled during private conversation.

Fig 8. James Sitsilt on the Cecil roll (detail), CP vol 224, membrane 1r. Reproduced with permission of the Marquess of Salisbury, Hatfield House.

It was during just such a conversation with Cecil that Edward Stradling was prompted to write his genealogy-filled story of the twelve knights who accomplished the winning of Glamorgan.Footnote 55 Stradling’s history was eventually printed in 1584 as part of David Powell’s Historie of Cambria, now called Wales.Footnote 56 Powell gathered various texts together to augment Caradoc of Llancarvan’s history, and Cecil’s collection was also a major source for his research. After Stradling’s account of the twelve legendary knights, Powell adds that other knights, including Cecil’s ancestor, aided in the conquest,

of whome Robert Sitsylt was one, who albeit he had no part of the said Lordship of Glamorgan (that I can read of) yet neuerthelesse, he was in respect of his good seruice there doone, preferred to the marriage of an inheritrice of great possessions in the land of Ewyas, and the countrie neere adioining. Of which Robert Sitsylt I find this that followeth, recorded in a verie ancient writing, conteining his whole genelogie of 16 descents of heires male lineallie; which writing for the more credit of the historie, I thought good here to insert, as followeth.Footnote 57

What follows is a close transcription of the English genealogy in CP vol 266. Occasional details have been added from elsewhere in the collection. After copying the genealogy’s entry on Baldwin, for example, Powell notes that ‘This man gaue certeine lands in the towneship of Kigestone, vnto the moonkes of Dore’, a detail that is taken from a charter included later in CP vol 266.Footnote 58 Other additions highlight the dispute of arms at Halidon Hill. The first entry is a generally close transcription of the Cecil genealogy, beginning ‘In the yeare of Christ 1091 Robert Sitsylt came with Robert Fitzhamon’. His son James has been given his own numbered entry, which has been augmented in significant ways:

2. James Sitsylt, tooke part with Mawd the empresse against king Stephen, and was slaine at the siege of the castell of Wallingford, An. 4. Stephan. hauing then vpon him a vesture, whereon was wrought in needle worke his armes or ensignes, as they be made on the toombe of Gerald Sitsylt in the Abbeie of Dore, which are afterward trulie blazed, in a iudgement giuen by commission of king Edward the third, for the ancient right of the same armes. This Iames had a sonne called Iames Sitsylt, and foure daughters.

Four additions have been made to the text in CP vol 266: The reference to Maud clarifies the allegiance of James Sitsylt; the date adds specificity, although Cecil’s marginal gloss in CP vol 266 claims that he died in ‘Stephani anno 5o’; the doublet ‘armes or ensignes’ links this passage with the dispute of arms, which typically refers to ‘ensignes’; and the specific reference to the blazon of the arms that will be given during the judgement (printed in blackletter) furthers the association between the arms in the reign of Stephen and their defence in the reign of Edward iii.Footnote 59 This association is once again made during the genealogy’s entry for John Sitsylt, the eleventh descendant in the line. The entry begins by quoting the manuscript genealogy, ‘Sir John Sitsylt knight, tooke to wife Alicia …’. The Cecil manuscript does not, at this point, mention that this John was involved in the dispute of arms, but Powell adds a note on the dispute, marked with an asterisk and printed in blackletter:

* In the time of the warres that King Edward the 3. made against Scotland, at a place called Halydon hill neere Barwick anno 6. Edward 3. there arose a great variance and contention betweene Sir William de Facknaham knight, on the one side approouant, and this Sir Iohn Sitsylt knight, on the other side defendant, for an ensigne of armes, that is to say; The field of ten barrets siluer and azure, supported of 5. scocheons sable charged with so manie lions of the first rampants incensed geuls, which ensigne both the parties did claime as their right. But as both the parties put themselues to their force to maintaine their quarell, and vaunted to maintaine the same by their bodies; it pleased the king that iustice should be yeelded for triall of the quarell, without shedding of bloud: and so the bearing of the ensigne was solemnlie adiudged to be the right of the said Sir Iohn Sitsylt, as heire of bloud lineallie descended of the body of Iames Sitsylt, Lord of Beauport slaine at the siege of Walingford, as before is declared. The finall order and determination of which controuersie is laid downe by Iohn Boswel gentleman, in his booke intituled The concords of Armorie, fol. 80. This Sir Iohn Sitsylt had a charge of men at armes, for the custodie of the marches of Scotland, in the 11. yeere of King Edward the third.Footnote 60

As in the 1568 edition of Legh’s Accedens, this passage is a close English summary of ‘A touts Angloys’. The date has been moved to the beginning of the text and the specific references to ‘moltes dites et lour escriptes, et les tesmoignes du Roy d’armes et dauter lieges le Roy’ have been replaced with a vague assertion that the dispute ‘should be yeelded for triall’. The first text in the pair, ‘Cest a tesmoigne’, is alluded to as ‘The finall order and determination’, thus echoing the opening line that claims that the text is ‘pur le determination final’ of the debate. Powell has also added the closing detail that John Sitsilt had charge of men at arms, this taken from a copy of a letter in CP vol 266.Footnote 61 Given this reliance on the Cecil manuscript, it is likely that the account of the dispute was also translated from that source, but Powell cites the previously printed version in John Bossewell’s Workes (which does not mention the ‘men at armes’), thus broadening the authority of the account. Like Bossewell, Powell also affirms that Cecil has provided copies of the documents from which his genealogy is transcribed. When Powell finishes copying the English genealogy, he adds a citation, again marked with an asterisk and printed in blackletter:

* These petegrees and descents I gathered faithfullie out of sundrie ancient records and euidences, whereof the most part are confirmed with seales autentike therevnto appendant, manifestlie declaring the antiquitie and truth thereof; which remaine at this present in the custodie of the right Honorable Sir William Cecill, Knight of the noble order of the Garter, Lord Burghley, and Lord high Treasurer of England, who is lineallie descended from the last recited Richard Sitsylt, father to Dauid Cecill, grandfather to the said Sir William Cecill now Lord Burghley.Footnote 62

The language here – of ancient records, evidences and seals – once again echoes the self-authorising language of the three Cecil manuscripts and Bossewell. It is part of the rhetoric of spurious genealogy. With the publication of Powell’s Historia, the full Cecil pedigree entered wide circulation. Only three years later, in 1587, it was quoted in its entirety (including Powell’s note on his sources) in the second edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles.Footnote 63

There is no reason to assume that Cecil had any direct influence on the second edition of Holinshed’s Chronicles, but the appearance of his pedigree in its pages ensured that it would be known to antiquarians and historians for centuries. In the nineteen years since the story of John Sitsilt and William Fakneham was hurriedly inserted into the second edition of Legh’s Accedens, the Cecil genealogy had been transformed from a simple list of names into a coherent narrative with supporting documentation. As these private papers expanded, Cecil, like other members of the Elizabethan nobility, also decorated his residence with murals depicting his ancestry and commissioned a fashionable heraldic pedigree roll to be shown to visitors. These private displays of the Cecil family’s antiquity certainly had more impact than most: Queen Elizabeth herself would have walked past the murals at Theobalds, perhaps pausing to reflect on the ‘Cecils’ claims to long-standing national prominence’.Footnote 64 But it was Cecil’s use of print that ensured that such claims were known throughout England. Gerard Legh may not have been thinking of Cecil when he originally devised the arms with lions rampand on five escotcheons. Richard Tottell and John Bossewell, in contrast, were acting as part of Cecil’s own project to enhance the antiquity and honour of his name. As the narrative of the Cecil family developed in private papers, the complete genealogy was made available to David Powell for his Welsh history, and this in turn was inserted into Holinshed’s national history.

Each public appearance of the genealogy not only expanded its reach, but increased its authority. Cecil’s private papers appeal to ancient documents and rolls of parchment, the authority of which is dependent on seals that cannot be read. Bossewell mentions this evidence, but his authority rests with Cecil himself, ‘the ryght honorable the Lorde of Burghley’. Powell also invokes the language of ancient parchment documents, but he also cites Bossewell for corroboration. The editors of Holinshed’s Chronicle cite both Bossewell and Powell. Such citations might seem circular, but the success of Cecil’s project is evident, as the rhetoric of authenticated antiquity continued to be used to praise the lineage of Cecil even after his death in 1598. Before Elizabeth died in 1603, a short biography of Cecil was produced, possibly by his secretary Michael Hicks.Footnote 65 The author defends the antiquity of Cecil’s lineage and name without providing many details. Cecil’s father, he claims, ‘was a Gentleman, descended from the Cecills of Haulterennes in Wales, a very auncient house, myself haveing seene many auncient authentique writings and evidences proving many lyneall descents, evene to himself, the copies whereof I have in my custody to shewe’.Footnote 66 Not only is the spelling ‘Haulterennes’ (for Alt-yr-ynys) found in the English pedigree (it is the same place-name painted on the wall of Theobalds that Gough read as ‘…diforcines’), but the language of this claim again echoes the many notes on Cecil’s genealogical documents and the printed citations of Bossewell and Powell. The documents’ claims to antiquity, in this instance, are more significant than any ancestors actually named in them. This biography was printed by the eighteenth-century antiquarian Arthur Collins, who was apparently unsatisfied with mere assertions of ancient descent and he added an ‘Account of the Family of Cecil’ as a prologue to the whole work. For this, he cites numerous printed sources, including Powell and ‘John Boswel’s Concords of Armory, fol. 80’.Footnote 67 Collins would later recycle this account in his Peerage of England, where Holinshed is added to bolster the list of sources.Footnote 68 Cecil’s attempts to disseminate the narrative of his chivalric ancestors and to provide authority for that narrative were thus remarkably successful. Based on the authority of Bossewell, Powell and Holinshed, Cecil’s narrative continued to appear in genealogical reference works for centuries, obscuring the fact that a few private papers, made available (and possibly simply made) by Cecil himself, lie behind these very public accounts.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material for this article is available online and can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S000358152100038X.

ABBREVIATIONS AND BIBLIOGRAPHY

Abbreviations

- Bodleian

-

Bodleian Library, Oxford

- BL

-

British Library, London

- CP

-

Cecil Papers, Hatfield House Archives