INTRODUCTION: THE PARADOXES OF DUTCH CELTIC FIELDS

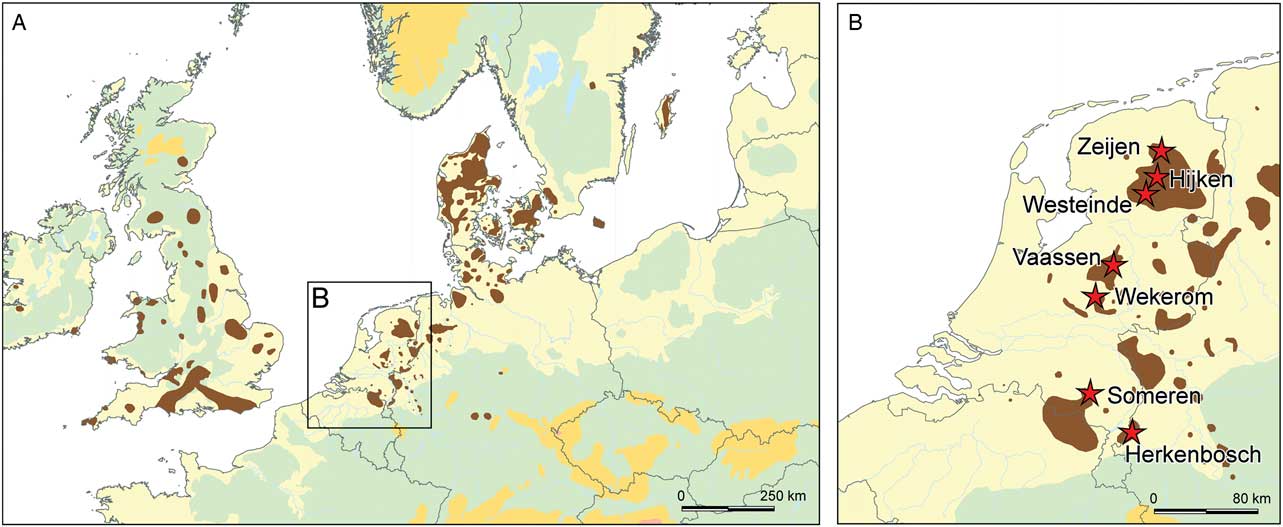

Prehistoric field systems in the Netherlands pose a paradoxical dataset: whilst over 350 locations of such field systems have been mapped (Fig. 1, B), very few of these have been excavated specifically to determine their age, extent, nature, or use-histories. Most of these are systems of embanked fields known nationally as raatakkers and internationally as ‘Celtic fields’. Among this large number of known sites, a substantial subset (n=168; Brongers Reference Brongers1976, pl. 10) were discovered on aerial photographs (Brongers Reference Brongers1976, 31–9), which signals yet another paradox: the very fact that these banks were visible in photographs of ploughed fields indicates that their quality of preservation (in terms of analysable sediments) is currently quite limited. For such locations, the potential for analysis of the field plots and banks to unravel agricultural use-histories is significantly reduced because of the levelling caused by agriculture.

Fig. 1 Distribution map of later prehistoric field systems (in brown) in north-western Europe (A: after Brongers Reference Brongers1976, 28, fig. 1 & Klamm Reference Klamm1993; additions by author), with the locations of the main investigated Dutch Celtic field sites marked as red stars in B

Fortunately, an increasing number of new ‘Celtic field’ locations have recently been discovered following the wider availability and increased resolution of LiDAR imagery. Ranging in scale from several to several hundred hectares in size, they support Yates’s (Reference Yates2007, 13) argument that field systems may represent prehistory’s largest – perhaps even monumental (Yates Reference Yates2007; Cooper Reference Cooper2016, 293) – legacy. Whereas aerial photography helped to discover Celtic fields primarily in cultivated fields, scrutiny of LiDAR imagery yielded a complementary set of Celtic fields in heathland and forested areas (eg, Bewley et al. Reference Bewley, Crutchly and Shell2005; Devereux et al. Reference Devereux, Amable, Crow and Cliff2005; Humme et al. Reference Humme, Lindenbergh and Sueur2006; De Boer et al. Reference Boer, de, Laan, Waldus and Zijverden2008; Kooistra & Maas Reference Kooistra and Maas2008; Clemmensen Reference Clemmensen2010; Hesse Reference Hesse2010; Arnold Reference Arnold2011; Meylemans et al. Reference Meylemans, Creemers, De Bie and Paesen2015). In such areas, devoid of recent construction and agricultural activities, banks of Dutch Celtic fields have been preserved up to heights of 90 cm (Van der Heijden & Greving Reference Heijden and Greving2009, 36). This quality of preservation renders such LiDAR-discovered sites ideal candidates for targeted fieldwork campaigns, in order to shed light on their agricultural role in the past.

This paper argues that we are still very poorly informed on three fundamental aspects of Celtic field agriculture. First, the palaeoeconomy and regional specifics of the agricultural regime responsible for the ubiquitous embanked fields are based mostly on assumptions, as only few sites have seen palaeoecological analysis. Secondly, the traditionally held view that Celtic fields were landscapes used for both habitation and cultivation is similarly based on very few excavated locations and appears to gloss over problems in dating and in the placement of houses with regard to the banks. Thirdly, despite the increase in known Celtic field sites, hardly any efforts have been made to date the start and use-life of Dutch raatakkers directly. In order to redress this imbalance, the results of several recent research excavations of Celtic fields across the Netherlands are presented below, and the extracted evidence on palaeoeconomy, settlement–field interrelations, and dating is discussed. Unfortunately, as the substantial dataset on Dutch later prehistoric field systems up to 2010 did not see much targeted excavation, it has remained problematic to evaluate the Dutch dataset of embanked fields within their wider European context: when did this system come into play in the Low Countries, what inspired it, and how long did it last? How do the Dutch raatakkers fit into the chronologies of later prehistoric field systems on the European and national levels? Ideally, their survival in the contemporary cultural landscape would have sparked more interest in such issues, yet the long but intermittent history of research into Dutch Celtic fields has focused more on mapping than on detailed understanding of the Celtic field phenomenon.

THE DEEP ROOTS OF DUTCH CELTIC FIELD STUDIES

The earliest reference to what we now recognise as Celtic fields in the Netherlands dates to the 17th century, when the Coevorden vicar Johan Picardt described and depicted a Celtic field as an encampment of the Suebi tribe. He also excavated one or more sites, as he recounts uncovering a stone-paved area the size of a cartwheel (Picardt Reference Picardt1660, 41–3). This (mis)interpretation of Celtic fields as military encampments was long lived, as the Leiden professor Caspar C. Reuvens visited the ‘encampments’ (legerplaatsen) of Drenthe in 1819, and again in 1833 (Brongers Reference Brongers1976, 19; Van der Sanden Reference Sanden2009, 17). Reuvens visited several Celtic field sites and had some mapped in detail; he subsequently started to question their interpretation, offering alternative hypotheses, such as they were areas for sheep-management (Brongers Reference Brongers1973, xxxi; Van der Sanden Reference Sanden2009, 17). Reuvens excavated one of these sites (at Exloo), but the results were never published (Janssen Reference Janssen1848, 109; Van der Sanden Reference Sanden2009, 17). The first more systematic examination of a Celtic field plot was undertaken by Leonhardt J.F. Janssen, then curator of the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, who dug trenches through the banks and field plots of the Zeijen-Noordse Veld Celtic field in 1848 (Fig. 2, C; Janssen Reference Janssen1848, 110–11). Judging by these trenches, he suspected a Germanic rather than a Roman origin, and – noting their association with barrows (cf. Van Giffen Reference Giffen1939, 88; Brongers Reference Brongers1976, 20; Cooper Reference Cooper2016, 303–5; Ten Harkel et al. Reference Harkel, ten, Franconi and Gosden2017, 418) – suggested that they might have played a part in funerary rituals (Janssen Reference Janssen1848, 122; Brongers Reference Brongers1976, 23; Van der Sanden Reference Sanden2009, 17), as he found no evidence for their use as settlements, garden plots, or sheep-pens (Janssen Reference Janssen1848, 121–2).

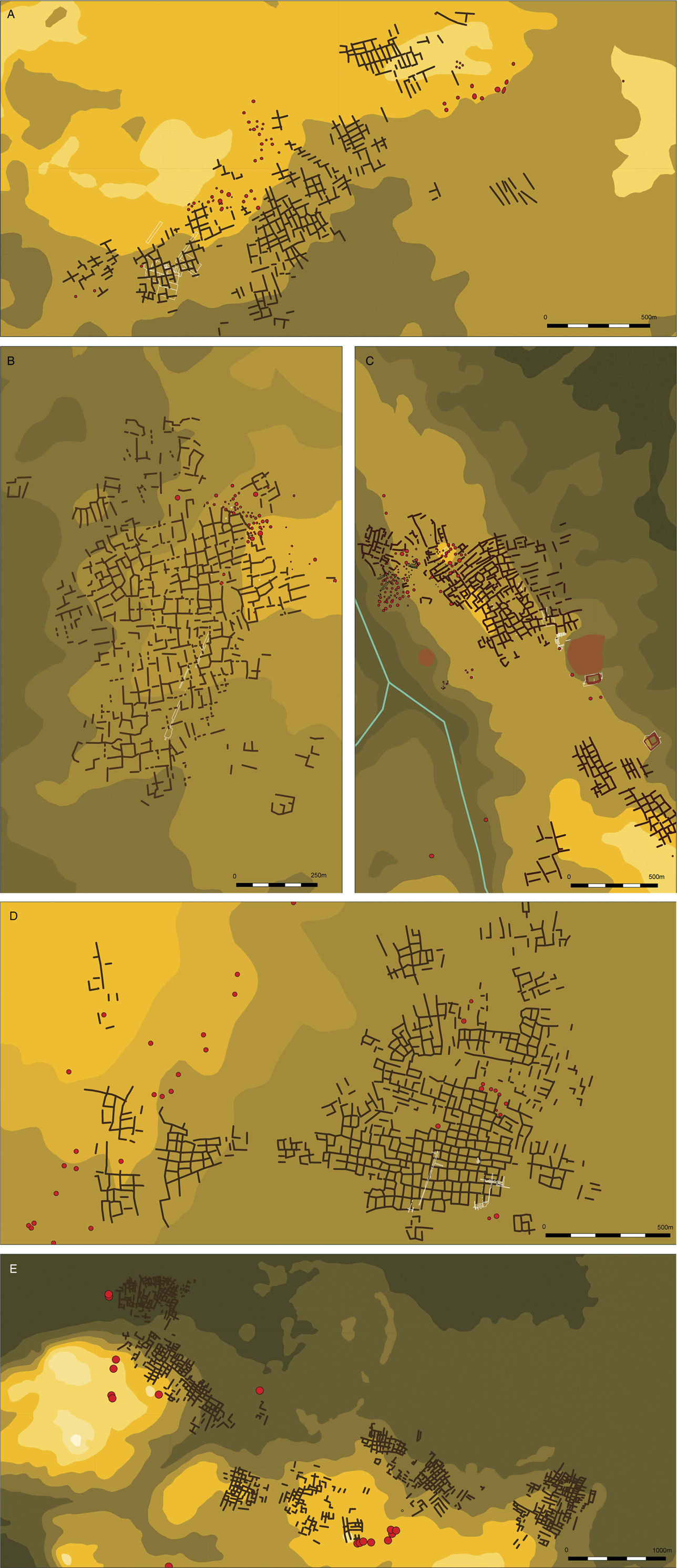

Fig. 2 Schematic plans of several Dutch Celtic fields. Contours: lower altitudes (brown) to higher locations (light yellow); Celtic field banks as brown polylines; barrows as red circles with black outlines; excavated areas indicated in white polygons. A: Hijken-Hijkerveld (after Harsema Reference Harsema1991; Arnoldussen & De Vries 2014); B: Westeinde-Noormansveld; C: Zeijen-Noordse Veld (after Van Giffen Reference Giffen1950; Waterbolk Reference Waterbolk1977; Spek et al. Reference Spek, Groenman-van Waateringe, Kooistra and Bakker2003; Reference Spek, Snoek, Sanden, van der, Kosian, Heijden, van der, Theunissen, Nijenhuis, Vroon and Greving2009; Arnoldussen Reference Arnoldussen2012); D: Vaassen (after Brongers Reference Brongers1976); E: Wekerom-Lunteren (after Van Klaveren Reference Klaveren1986; Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014)

It was not until the first decades of the 20th century that Celtic fields received renewed archaeological attention: between 1917 and 1944, Groningen professor of archaeology Albert E. Van Giffen excavated several ‘so-called heathen military camps’ (heidensche legerplaatsen – Van Giffen Reference Giffen1918; Reference Giffen1934; Reference Giffen1935; Reference Giffen1940; Reference Giffen1943), although he proposed no clear hypothesis on their function initially (Brongers Reference Brongers1976, 24; Van der Sanden Reference Sanden2009, 19). Taking inspiration from Curwen and Curwen’s (Reference Curwen and Curwen1923) and Hatt’s (Reference Hatt1931) identifications of later prehistoric field systems (as Celtic fields and porsehaver, respectively; Brongers Reference Brongers1976, 24), Van Giffen stated, in 1939, that the Dutch raatakkers or heidensche legerplaatsen were no different, an observation supported by the discovery of post-holes and cultivation traces (spade or ard-marks) in the Zuidveld Celtic field (Van Giffen Reference Giffen1939, 87, 90, 92). Between 1939 and 1941, the National Museum of Antiquities curator, Wouter C. Braat, dug numerous test-trenches through the Celtic field of Wekerom-Lunteren (Fig. 2, E), uncovering a series of plans of Iron Age farmhouses and outbuildings (see Fig. 5, A; Van Klaveren Reference Klaveren1986; Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014, 13–20). The Celtic field of Zeijen-Noordse Veld received most, albeit intermittent, attention from Van Giffen, who excavated this cluster of Celtic fields, barrow groups, and settlement traces between 1917 and 1954 (Brongers Reference Brongers1976, 26; Van der Sanden Reference Sanden2009, 20; Arnoldussen Reference Arnoldussen2012, 20, fig. 13).

As part of his PhD study of Dutch Celtic fields, Ayolt Brongers excavated 0.3 ha of the Vaassen Celtic field (Fig. 2, D), targeting both banks and fields, and uncovering part of an Iron Age house site (Brongers Reference Brongers1976, 44–5). Few other Celtic field excavations were carried out in the second half of the 20th century. An important exception was the excavations at Hijken (Fig. 2, A; Fig. 5, C; Harsema Reference Harsema1991; Arnoldussen & De Vries Reference Arnoldussen and Vries2014), in which the interrelation of Celtic fields with Bronze and Iron Age habitation could be studied. Similarly, an excavation at Peelo-Kleuvenveld uncovered two or three Iron Age house plans amidst the Celtic field plots (Fig. 5, B; Kooi & De Langen Reference Kooi and Langen1987). Yet in general terms, the interrelation of houses and field plots is still poorly understood (Arnoldussen & De Vries 2017). It would take until the first decades of the 21st century for research specifically aimed at unravelling the Dutch Celtic field use-histories to be published (eg, Spek et al. Reference Spek, Groenman-van Waateringe, Kooistra and Bakker2003; Reference Spek, Snoek, Sanden, van der, Kosian, Heijden, van der, Theunissen, Nijenhuis, Vroon and Greving2009; Arnoldussen Reference Arnoldussen2012; Groenman-Van Waateringe Reference Groenman-van Waateringe2012; Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014; Arnoldussen et al. Reference Arnoldussen, Schepers and Maurer2016).

PROBLEMATIC DEFINITION: WHAT DO WE NEED TO KNOW ABOUT CELTIC FIELDS?

I have already argued above that Celtic field research has a considerable time depth, but has seldom explicitly addressed the knowledge gap of their dating and agricultural use. In part, this is understandable from a historical perspective in which focus was first on ascertaining the true nature of this type of site (period c. 1660–1939), and thereafter, attention turned towards a culture-historical analysis of the houses and plots uncovered within them (period c. 1953–1991). Whilst the latter still merits additional study (cf. Arnoldussen & De Vries Reference Arnoldussen and Vries2014; Reference Arnoldussen and Vries2017), any new research into the (long term) development of Celtic fields must include efforts to establish Celtic field chronologies (cf. Gerritsen Reference Gerritsen2003, 174–8).

The generally assumed Late Bronze Age–Iron Age date for Dutch Celtic fields (eg, Spek et al. Reference Spek, Groenman-van Waateringe, Kooistra and Bakker2003, 142; Harsema Reference Harsema2005, 543; Kooistra & Maas Reference Kooistra and Maas2008, 2319) is often based solely on typochronological characterisation of the pottery or houses recovered in them (eg, Brongers Reference Brongers1976, 64; Waterbolk Reference Waterbolk1977; Kooi & De Langen Reference Kooi and Langen1987, 55(155), 60(160); Harsema Reference Harsema1991, 29). Where radiocarbon-dated samples are available (Brongers Reference Brongers1976, 52–5, 62–3; Spek et al. Reference Spek, Groenman-van Waateringe, Kooistra and Bakker2003, 165), their relation to the encasing sediment and original surface is often unclear, because of the dynamic genesis of the sample contexts (anthropogenic: ploughed fields or constructed banks; Waterbolk Reference Waterbolk1949, 138, cf. Sharples Reference Sharples2010, 36–7). Such problems can only be avoided by using direct dating techniques such as Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL; cf. Wallinga & Versendaal Reference Wallinga and Versendaal2013a–Reference Wallinga and Versendaalb; Voskuilen et al. Reference Voskuilen, Reimann and Wallinga2016) or larger numbers of radiocarbon dates that allow us to identify (and omit) anomalies.

Secondly, archaeologists need to focus more on establishing the particulars of the agricultural system in question. Frustratingly, despite there being several hundred known Celtic fields, only very few have been investigated for details of their agricultural system. This means we are poorly informed on (a) the types of crops grown; (b) any use and duration of fallow cycles; (c) materials and frequency of manuring; (d) methods of tillage; and (e) presence and possible dominance of grassland plots versus plots for crop cultivation. Prior research has attempted to tackle such questions mainly through the application of palynology.

An early palynological investigation of the Celtic field layers underlying barrows at Zeijen-Noordse Veld found 1–10% Cerealia pollen in the samples (Van Giffen Reference Giffen1949, 116, 122; Waterbolk Reference Waterbolk1949, 140, 143), with indications for hoe-based tillage and waste manuring (Van Giffen Reference Giffen1949, 117, 118, 121). In 1976, the excavations at Vaassen (Fig. 2, D; Brongers Reference Brongers1976) also included palynological studies, but unfortunately only two samples, showing poor preservation, from the Celtic field banks were analysed and showed pollen of Cerealia (0.6–5% Triticum/Hordeum-type; Casparie Reference Casparie1976, 107–8, fig. 10). Casparie noted the relatively strong presence of grasses and hornworts (Phaeoceros laevis/punctatus; Casparie Reference Casparie1976, 109, 111) in these samples, and speculated whether high numbers of herbs reflected bank vegetation or vegetation of fallow fields resulting from multiple-course rotation systems (ibid., 110). The low amounts of ling (Calluna) and beech (Betula), according to Casparie, argued against long fallow periods (ibid., 112). Moreover, high percentages of sedges (Cyperaceae; 8.5–22.1%) and spurrey (Spergula; 1.5–15.3%) were noted (Casparie Reference Casparie1976, 106–7, table 4). Whereas the latter may have been a crop rather than an arable weed (ibid., 112, cf. Odgaard Reference Odgaard1985, 127; Holden Reference Holden1997, 53), the high amount of sedges could represent introduced wetland sods (used as byre bedding), fodder, or muck manure (Arnoldussen & Vander Linden Reference Arnoldussen and Linden2017).

The palynological investigations of the Zeijen Celtic field in 1993 by Spek et al. (Reference Spek, Groenman-van Waateringe, Kooistra and Bakker2003, 155–62) started a new phase of research, yet their sample location was much affected by poor preservation (five samples were sterile) and contamination (as shown by pollen of buckwheat washed downwards in the section). Considering only those samples below the deepest levels of contamination, the presence of Cerealia non secale, Secale, and spurrey could be documented. No botanical macro-remains were found, but it is unclear whether any sieving was undertaken to recover such remains. This 1993 campaign should be lauded for its integrated interdisciplinary approach: the same sections investigated palaeoecologically were also studied for their pedology and soil micromorphology, making it possible to postulate that the initial phase of use was marked by an extensive mode of exploitation involving clearance fires, long fallow periods, and manuring (Spek et al. Reference Spek, Groenman-van Waateringe, Kooistra and Bakker2003, 164–5, but see Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014, 58, 86). Moreover, ard tillage of the banks was postulated (Spek et al. Reference Spek, Groenman-van Waateringe, Kooistra and Bakker2003, 164). In later (Late Iron Age/Roman period) use-phases of the Celtic field, abundance of pollen in the higher sections of bank was taken to represent less burning and (hence) shorter fallow periods, and high values for grasses and sorrel were taken to indicate that some plots were used for grazing (ibid., 165). Additionally, the latest use-phase showed an influx of organic topsoil or litter from outside the Celtic field and intensification reflected in reduced particle sizes (through more frequent tillage) and increased phosphate content (ibid., 166; but see Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014, 86 on alternative phosphate distributions).

To sum up the recent inquiries, it remains striking that only very few targeted excavations of Dutch Celtic fields have been undertaken. Consequently, there have remained several problems in the determination of Celtic field chronologies, complicating the pinpointing of the establishment, overall life span, and duration of use-cycles of Celtic fields. Moreover, only a very restricted set of proxies for agricultural parameters such as crop rotation, fallow duration, and manuring regime have been studied for a very restricted set of sites (n=3). These problems prompted the Groningen Celtic fields project.

THE GRONINGEN CELTIC FIELDS PROJECT: THREE SCALES OF STUDY

In 2012, I initiated the Celtic fields project in order to fill various knowledge gaps in our understanding of long term agricultural landscape development through targeted excavations in Dutch Celtic fields. These were all research excavations undertaken by Groningen University and various governmental and heritage partners (ie not developer-led projects), which allowed a research question-driven (rather than location-/developer-driven) approach with flexible planning and detailed sampling strategies. This long term research programme studies Celtic fields on three complementary scales (each with their own pertinent questions).

At the macro-scale, the similarities and differences in form and agricultural use-strategies for Celtic fields situated in different geogenetic settings are studied. Is it that similarities in morphology of embanked field systems across different geogenetic backdrops reflect a highly adaptable agricultural strategy? Or conversely, were communities in different geogenetic regions doing the same despite such differences (cf. English Reference English2013, 15)? To answer these types of questions, a series of excavations of Celtic fields in landscapes of different geological genesis is required. Therefore, Celtic fields have been excavated on Saalian boulder-clay plateaus (Zeijen-Noordse Veld, Westeinde-Noormansveld; Arnoldussen Reference Arnoldussen2012; Arnoldussen & De Vries Reference Arnoldussen and Vries2017), on Saalian ice-pushed riverine and fluvioglacial deposits (Wekerom-Lunteren; Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014), on Weichselian coversand deposits (Someren-De Hoenderboom; Arnoldussen Reference Arnoldussen2013), and Middle Pleistocene river deposits underneath a Weichselian coversand layer (Herkenbosch-De Meinweg; Arnoldussen et al. Reference Arnoldussen, Scheele and de Kort2014). For these locations, the morphology of the bank systems as well as the composition of excavated fields and banks may be compared.

At the intermediate (meso-) scale, understanding the development and functioning of the individual Celtic field complexes was the primary objective. How did larger complexes (up to 210 ha; Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014) evolve? Were banks present from the onset (cf. Gerritsen Reference Gerritsen2003, 174–8) or did they gradually develop? Is there a deliberate interweaving of habitation (house sites) and field plots, as suggested by artists’ reconstructions (Fig. 3; cf. Arnoldussen & De Vries Reference Arnoldussen and Vries2017), or was this relation more dynamic (cf. Gosden Reference Gosden2013)? Moreover, this is the scale at which the morphological patterns mapped through LiDAR or aerial photography are operationalised into discussions of Celtic field development, Celtic field expansion, and studies of tenurial regimes (cf. Schrijver Reference Schrijver2011; Van Wijk Reference Wijk2015).

Fig. 3 Details of artists’ impressions of Celtic fields, exemplifying the presumed interrelations of houses and fields. Clockwise from top left: © Gemeente Ede, © Drents Museum, © Provincie Drenthe, © S. Drost

The micro-scale of the Groningen University Celtic field programme concentrates on reconstructing the age and uses of individual Celtic field plots and banks. This entails careful excavation of different plots and adjacent banks in several parts of a given field complex. By combining traditional archaeological approaches (sieving, AMS and OSL dating, artefact analyses) with pedological analyses (geochemistry, soil micromorphology), and palaeoecological analyses (palynological, botanical macro-remains, non-pollen palynomorphs; Arnoldussen & Van der Linden Reference Arnoldussen and Linden2017), the use-histories of Celtic field plots may be unravelled.

In what follows, results of the Groningen Celtic field projects are discussed across these three scales. At the macro-scale, a reappraisal of Celtic field palaeoeconomy is offered; on the meso-scale, the interrelations of houses and fields are addressed. This is followed by a discussion at the micro-scale of Celtic field dating results.

PALAEOECONOMY

On the macro-scale, the potential for obtaining meaningful results is in no small part dependent on the preservation conditions for evidence of past agricultural practice, which could provide essential data on crops sown, fallow and crop-rotation cycles, manuring strategies, etc (Klamm Reference Klamm1993, 50, 80). Consequently, the fact that, at the aforementioned recently excavated Someren and Herkenbosch fields, no charred botanical macro-remains were recovered (Arnoldussen et al. Reference Arnoldussen, Scheele and de Kort2014; Reference Arnoldussen, Schepers and Maurer2016) hampers any supra-regional comparison of crops cultivated or fallow cycles. Moreover, a more methodological study into the origins and compositions of the charred macro-botanical remains in Celtic field sediments (Arnoldussen & Smit Reference Arnoldussen and Smit2017) suggests that such remains were most probably brought onto the fields as fortuitous elements of household waste (as, or in, manure) rather than reflect crops and weeds grown locally (Müller-Wille Reference Müller-Wille1965, 93; Arnoldussen Reference Arnoldussen2012, 43–6; Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014, 60–1). This is best demonstrated by (a) the fact that species which require no charring as part of their preparation, preservation, or consumption (ie flax, millet) do occur solely in a burnt state, and (b) the fact that the rates of occurrence for cereals and arable weeds are discouragingly low (1.5–5 charred seeds for every 100 litres of Celtic field sediment; Arnoldussen & Smit Reference Arnoldussen and Smit2017). After sieving and screening over 1400 litres of Celtic field sediment from Westeinde-Noormansveld, and an additional 600 litres at Someren-De Hoenderboom, I am confident in stating that this low seed recovery rate is not an artefact of small-sample bias, but of past agricultural strategies in which household debris (marked by charcoal from firewood, burnt dung, and small ceramic sherds; Arnoldussen Reference Arnoldussen2012; Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014; Arnoldussen & vander Linden Reference Arnoldussen and Linden2017) was (mixed with dung and) used as a manuring agent (cf. Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann1976, 86; Behre Reference Behre2000, 141; Vanmontfort et al. Reference Vanmontfort, Langohr, Marinova, Nicosia and Van Impe2015, 142).

Whereas I have argued in the above section that it is ill advised to rely (solely) on botanical macro-remains for studying past agricultural strategies, the pollen contents of Celtic field plots and banks appear to be a far more promising record source. Despite inherent problems of mixing (by ards or hoe-type implements; cf. Brongers Reference Brongers1976, 51) and contamination (pollen infiltration through seepage and biological agents [eg, bees, beetles, roots] as well as supra-local influx), careful analysis of the pollen contents of field plot and bank sediments has yielded valuable information. Moreover, the durability of pollen allows interregional comparisons even of sites that show no preservation of uncharred macro-remains (the matter of geogenetic differences and field system similarities is addressed in the final section of this paper). Pollen of Triticum/Hordeum type or, in older studies, Cerealia-pollen, were found in almost all studied Celtic fields, with Triticum dicoccum identified at Wekerom (Fig. 4, cf. Müller-Wille Reference Müller-Wille1965, 94; Behre Reference Behre2000, 138, 140, abb. 5). The few surviving macro-fossils suggest that – as these species were present in the settlements from which the fields were manured – barley, bread wheat, millet, and flax were also grown (Behre Reference Behre2000, 138, 140, abb. 5, cf. Helbæk in Hatt 1949; Müller-Wille Reference Müller-Wille1965, 94; Kroll Reference Kroll1987, 375). As to flax, the presence of Linum pollen in the Zeijen-Noordse Veld fields documents the cultivation of this species in Celtic field plots (Arnoldussen Reference Arnoldussen2012; Arnoldussen & vander Linden Reference Arnoldussen and Linden2017). Pollen of grasses are ubiquitous in the various Celtic field plots studied, frequently accounting for half of the pollen sum (Fig. 4). This suggests that grazed grassland plots played a significant part in the Celtic field economy. At Someren-De Hoenderboom, the fluctuating and repeatedly high percentages of grasses and ling (Calluna), combined with coprophilous herbivore dung fungi (Sordaria-type), suggest that several plots of that Celtic field must have been used for grazing (Arnoldussen et al. Reference Arnoldussen, Schepers and Maurer2016). However, it still remains unclear what proportion of field plots may have been used for grazing, or according to what cycles (as part of fallow regimes?) those plots were not cultivated. Moreover, an inter-regional comparison of plant species that may yield information on fallow durations (eg, biennials) and of nutrient conditions (eg, nitrogen and phosphate proxies, stable isotopes) is yet to be undertaken.

Fig. 4 Palynological (pollen) and macrobotanical (macro-)remains of foodcrops and a selection of cultural and landscape indicators for Dutch Celtic fields. Cerealia=cereals, indet.; Triticum dicoccum=emmer wheat; Hordeum=barley; Secale cereale=rye; Panicum miliaceum=millet; Linum usitatissimum=flax/linseed; Spergula=spurrey; Gramineae=grasses; Plantago=plantain; Cyperaceae=sedges; Sparganium=bur-reed; Typha=bulrush; Phaeoceros=hornworts

Despite these observations on the nature of Dutch Celtic field farming, it should be stressed that various specifics of the agricultural strategy, such as the balance of livestock rearing versus crop cultivation, crop rotation strategies and the role of fallow periods, remain poorly understood (cf. Jankuhn Reference Jankuhn1958, 203, 205; Fowler Reference Fowler1983, 112; Klamm Reference Klamm1993, 50, 80;). Possibly, the dominance of wild herbs and arable weeds over cereals may one day prompt the conclusion that fallow periods were an integral part of the agricultural strategy (Becker Reference Becker1971, 97–8; Groenman-Van Waateringe Reference Groenman-van Waateringe1980, 364–6; Liversage et al. Reference Liversage, Munro, Courty and Nørnberg1985; Odgaard Reference Odgaard1985; Klamm Reference Klamm1993, 81). Behre (Reference Behre2008, 155) assumes that at most 10% of the Flögeln Celtic field plots were in use simultaneously, suggesting a regime of extensive use (cf. Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann1976, 88–9; Smith Reference Smith1996, 214; Spek et al. Reference Spek, Groenman-van Waateringe, Kooistra and Bakker2003; Løvschal & Holst Reference Løvschal and Holst2014, 8). For the Danish site of Grøntoft, Odgaard (Reference Odgaard1985, 127) argued that the nutrient status of the fields allowed tillage over longer periods with minimal, if any, fallow.

HOUSE AND FIELD INTERRELATIONS

At the meso-scale, the developmental histories of individual Celtic field complexes were investigated. This entailed a combination of re-analyses of previously excavated Celtic fields with new, targeted fieldwork. A complicating factor is that the inherently destructive nature of excavation means that it is costly in terms of ‘scientific gain/loss’ (as well as in financial terms) to uncover Celtic fields to the extent required to study the interrelations between habitation and agriculture. Ideally, one would topsoil-strip known Celtic fields where the banks had already been levelled by erosion and/or modern agriculture; in such locations, a broad perspective on the degree and nature of activities taking place in the fields might be obtained, without the loss of evidence involved in levelling banks and stripping fields during an excavation. At locations where bank or field sediments have been preserved, I would argue that excavating these in full would cause an irresponsible loss of evidence, and test-trenches are perhaps more appropriate. Fortunately, the long research history into Dutch Celtic fields provides us with an (albeit limited) dataset on previously excavated Celtic fields.

As I have dealt with the awkward interrelations between house sites and Celtic field plots in more detail elsewhere (Arnoldussen & De Vries Reference Arnoldussen and Vries2017), I shall only briefly summarise the main conclusions here. First, it seems that the habitation features uncovered in Dutch Celtic fields span the Early to Late Iron Age period (c. 800 bc–12 bc; for the chronology see Van den Broeke et al. Reference Broeke, van den, Fokkens and Gijn2005), and the longhouses of those periods often appear to be situated (partly) on the banks (Fig. 5), in spite of popular artists’ impressions (Fig. 3) that slot them neatly into field plots (cf. Bradley Reference Bradley1978, 272). The observations that at several excavations multiple house sites were uncovered – eg, five at Wekerom (Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014, 15, fig. 8) and at least eight at Hijken (Arnoldussen & De Vries Reference Arnoldussen and Vries2014, 93, fig. 7) – and that even at sites with a much lesser degree of investigation house sites were still found, suggest that up to 20% of field plots may have supported habitation at some given point in time (Arnoldussen & De Vries Reference Arnoldussen and Vries2017). Evidently, the time depths involved in house site (re)location are restricted compared to those of bank formation (infra), and – despite the often limited size of the excavations – the excavated sites suggest that house plans uncovered within Celtic fields appear not to reflect the Celtic fields’ integral use-life. The conformity in structural details and shared orientation of these houses (cf. Fig. 5) indicate broad contemporaneity and suggest that habitation occurred only during specific parts of the Celtic field’s much longer (infra) use-life.

Fig. 5 Association of Iron Age house sites (houses in blue and outbuildings in red) with Celtic field banks (brown) at three larger Celtic field excavations. Excavated areas in white. Not to the same scale. A: Wekerom-Lunteren (after Van Klaveren Reference Klaveren1986; Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014); B: Peelo-Kleuvenveld (after Kooi & De Langen 1987); C: Hijken-Hijkerveld (wattlework fences as black outlines; after Harsema Reference Harsema1991; Arnoldussen & De Vries 2014)

At the sites of Vaassen and Hijken there is evidence to suggest that Celtic field banks were bounded by or succeeded wattle fencing (Vaassen: Brongers Reference Brongers1976, 52; Hijken: Arnoldussen & De Vries Reference Arnoldussen and Vries2014, 101, fig. 12). These two observations suggest that the initial planning of Dutch Celtic field landscapes may have relied on fences that were later substituted by banks (cf. Becker Reference Becker1971, 103–4; Løvschal Reference Løvschal2015, 261). The banks themselves contain a mixture of settlement debris (firewood charcoal, sherds, burnt dung, burnt cereals), dung (as indicated by coprophilous herbivore-dung fungi), dislocated clastic elements (possibly sods used previously as byre bedding; cf. Kroll Reference Kroll1987; Liversage & Robinson Reference Liversage and Robinson1993, 51; Bradley Reference Bradley1978, 272; Behre Reference Behre2000, 142; 2008, 154–5), and wetland indicators (sedges, reeds, freshwater algae, remains of either wetland sods or fodder). Because of this, I have suggested (Arnoldussen Reference Arnoldussen2012, 57–60; Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014, 88–92; Arnoldussen & vander Linden Reference Arnoldussen and Linden2017) that the banks’ composition mirrors that of the fields that they enclose; presumably the banks increased in height through the deposition of uprooted plants with soil attached to their roots, or by stripping the fallow fields’ turf and dumping this at the field’s margins (a process in which the organic waste piled high enough to make redundant the function of the initially present fencing). In the words of Løvschal (Reference Løvschal2014, 736), ‘… repeated use had a clear cumulative effect, leading to some parts becoming more materially stable, higher, and more visually prominent than others. Moreover, as soon as they had become established as visual banks or walls, they gained a certain degree of inertia’.

The above interpretation of gradual bank formation through recurring agricultural activities (manuring, weeding, field preparation) by which sediment accumulated into banks, implies that the banks themselves may form chronostratigraphic records of the agricultural use-history of the plots they enclose. To test this hypothesis, detailed analytical and dating efforts on sections of individual Celtic field banks are required.

DATING DUTCH CELTIC FIELDS

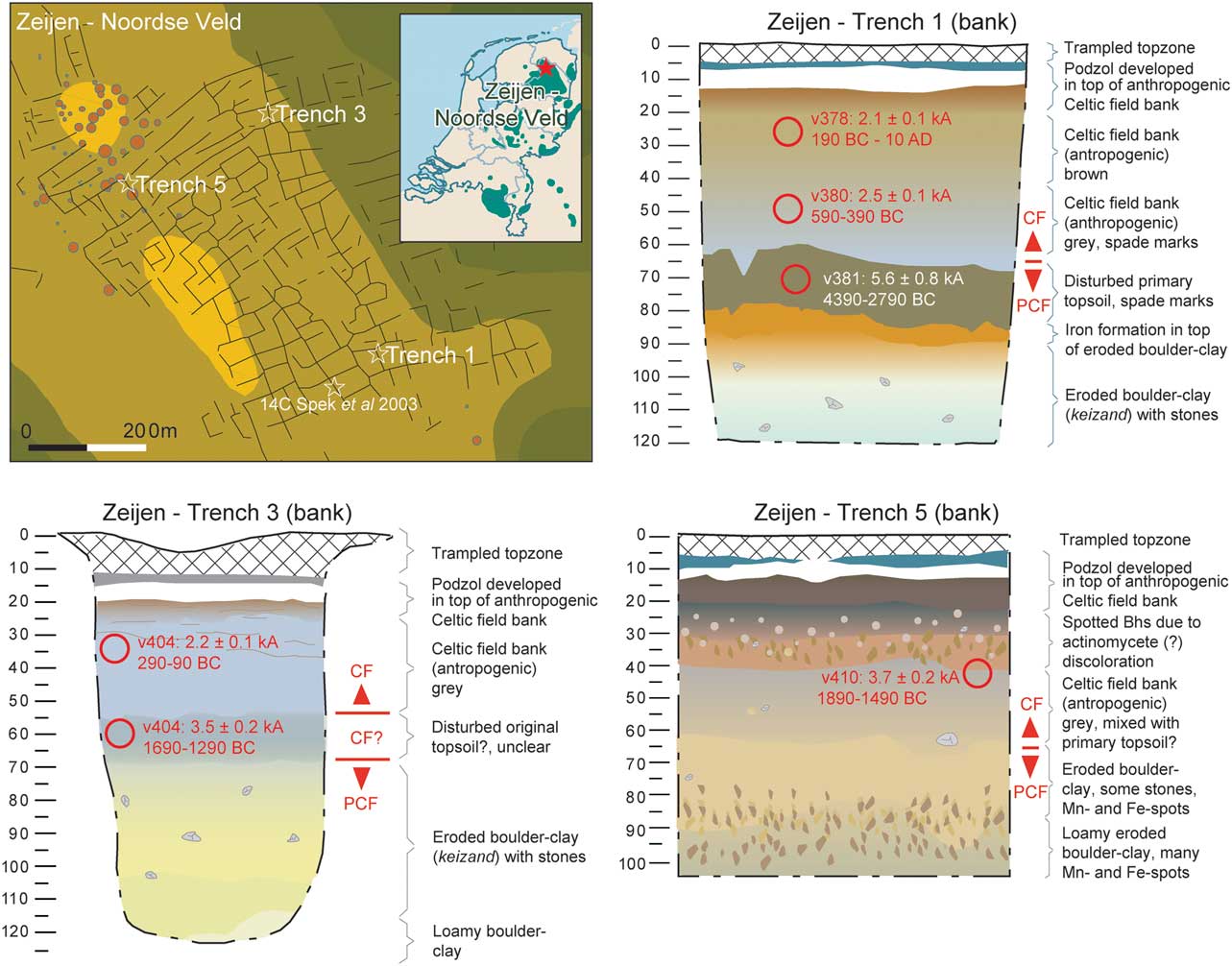

The dating of Celtic fields (or their banks) is difficult. Based on pottery frequently recovered from the banks, a Late Bronze Age/Early Iron Age usage may be expected (Arnoldussen Reference Arnoldussen2012, 54; Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014, 80). Radiometric dating can refine this, but the interpretative strength of single radiocarbon dates from banks is strongly reliant on the understanding of their complex lithogenetic context and sample quality. For the radiocarbon samples obtained previously at Vaassen, their lithogenetic context was often unclear (Brongers Reference Brongers1976, 64, 104), albeit Early Bronze Age terminus post quem dates and Early Medieval terminus ante quem dates (ibid., 53, 104) are undisputable. The relevance of the single Middle–Late Iron Age radiocarbon date obtained for the Zeijen-Noordse Veld bank (Fig. 6; Spek et al. Reference Spek, Groenman-van Waateringe, Kooistra and Bakker2003, 165) is difficult to determine, as it is unclear where the original surface was located, but the date suggests bank development after the Middle Iron Age.

Fig. 6 Overview and geogenetic interpretation of Celtic field banks at Zeijen-Noordse Veld (after Arnoldussen Reference Arnoldussen2012; dates: Wallinga & Versendaal Reference Wallinga and Versendaal2013b). The locations of the OSL samples are indicated as red circles

To avoid the known problems of radiocarbon dating (known age of sample, risk of bioturbation), the Groningen Celtic field programme has relied on Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating of the bank sediments proper. For the samples here discussed, at least 21 aliquots per sample (average 175 grains, 180–212 μm, chemically pre-treated with HCl > H202 > HF > HCl rinsing) were dated, using the Central Age Model (CAM) and a ‘bootstrapping’ approach (full methodology: Wallinga & Versendaal Reference Wallinga and Versendaal2013a–Reference Wallinga and Versendaalb; Voskuilen et al. Reference Voskuilen, Reimann and Wallinga2016). By using this technique with several samples from individual banks at Zeijen, Wekerom, and Someren, it could be determined when bank development occurred and whether this was a one-off event or a long term trajectory. AMS dating was used additionally (at Someren) or instead (at Westeinde) to establish the use-life of the Celtic field banks at these sites.

Zeijen-Noordse Veld

Despite its long research tradition (supra), prior research at Zeijen had not yielded very precise dates for the use of the Celtic field. In 1918, Van Giffen could not identify the recovered pottery more closely than as being of ‘Germanic’ origin (Van Giffen Reference Giffen1918, 153), and for the Middle Iron Age pottery recovered in 1953 (Waterbolk Reference Waterbolk1977, fig. 8; Taayke Reference Taayke1996, 67, 72, n. 261) its stratigraphic position with regard to the banks is unclear (Arnoldussen Reference Arnoldussen2012, 17). A more solid stratigraphic resource was a cinerary barrow on top of a Celtic field bank, which yielded an urn that Van Giffen dated to the final Bronze Age (Van Giffen Reference Giffen1949, 119, fig. 20, 137) – but which since has been dated typologically to the Late Iron Age (Glasbergen Reference Glasbergen1954, 70; Brongers Reference Brongers1976, 26). A radiocarbon date of 384–198 cal bc (UtC-3073: 2240±40 bp; Spek et al. Reference Spek, Groenman-van Waateringe, Kooistra and Bakker2003, 165) obtained at 55 cm depth from a nearby bank (Spek et al. Reference Spek, Groenman-van Waateringe, Kooistra and Bakker2003, 163, fig. 6; see Fig. 6 for location) can only provide a general terminus ad quem date, as its stratigraphic position with respect to the underlying surface is unclear; in other words, one cannot determine whether it relates to early, middle, or late bank formation.

Based on the Groningen Celtic field project excavations, the oldest agricultural phases, presumably predating bank formation, were dated to 4390/2790 bc (bank 1) and 1680/1280 bc (bank 3) (Wallinga & Versendaal Reference Wallinga and Versendaal2013b, 6, tab. 2). The homogenisation of those layers, and particularly the presence of hoe- or spade marks at this level in trench 1 (Arnoldussen Reference Arnoldussen2012, 28–9), indicate that agriculture was already practised before bank development took place, as the original primary soil was disturbed and incorporated into these layers (Fig. 6; cf. Van Giffen Reference Giffen1940, 202). A 4th millennium date for the lowermost sample from trench 1 may be related to Funnel Beaker period activity, as a Middle Neolithic passage grave is situated at 750 m south-west of trench 1 (Van der Sanden Reference Sanden2012, 28). For trench 3, the lowermost sample suggests that homogenisation of the primary surface took place early in the Middle Bronze Age (17th–14th centuries bc) – again hinting at a phase of agriculture predating bank development.

The sample from the lowermost third part of the bank sediment in trench 5 suggests that bank construction may have taken place even before the 15th century bc. A sample from a similar stratigraphic position in trench 1 indicates that for other banks an Early Iron Age terminus ante quem is probable. Younger OSL dates from higher up in the banks indicate that the vertical aggradation of the banks will have been a slow process (cf. Arnoldussen & vander Linden Reference Arnoldussen and Linden2017): the topmost samples from trenches 1 and 3 both indicate a Late Iron Age (c. 3rd/2nd century bc–ad 1) usage. The facts that (a) the topmost OSL dates were taken at locations 25–30 cm down from the bank’s top (to avoid contamination caused by bioturbation), and (b) the present day bank is likely to be lower than it was in prehistory as a result of subsequent wind erosion, trampling, and possibly Medieval sod cutting, suggest that bank formation at Zeijen continued well into the Roman Era.

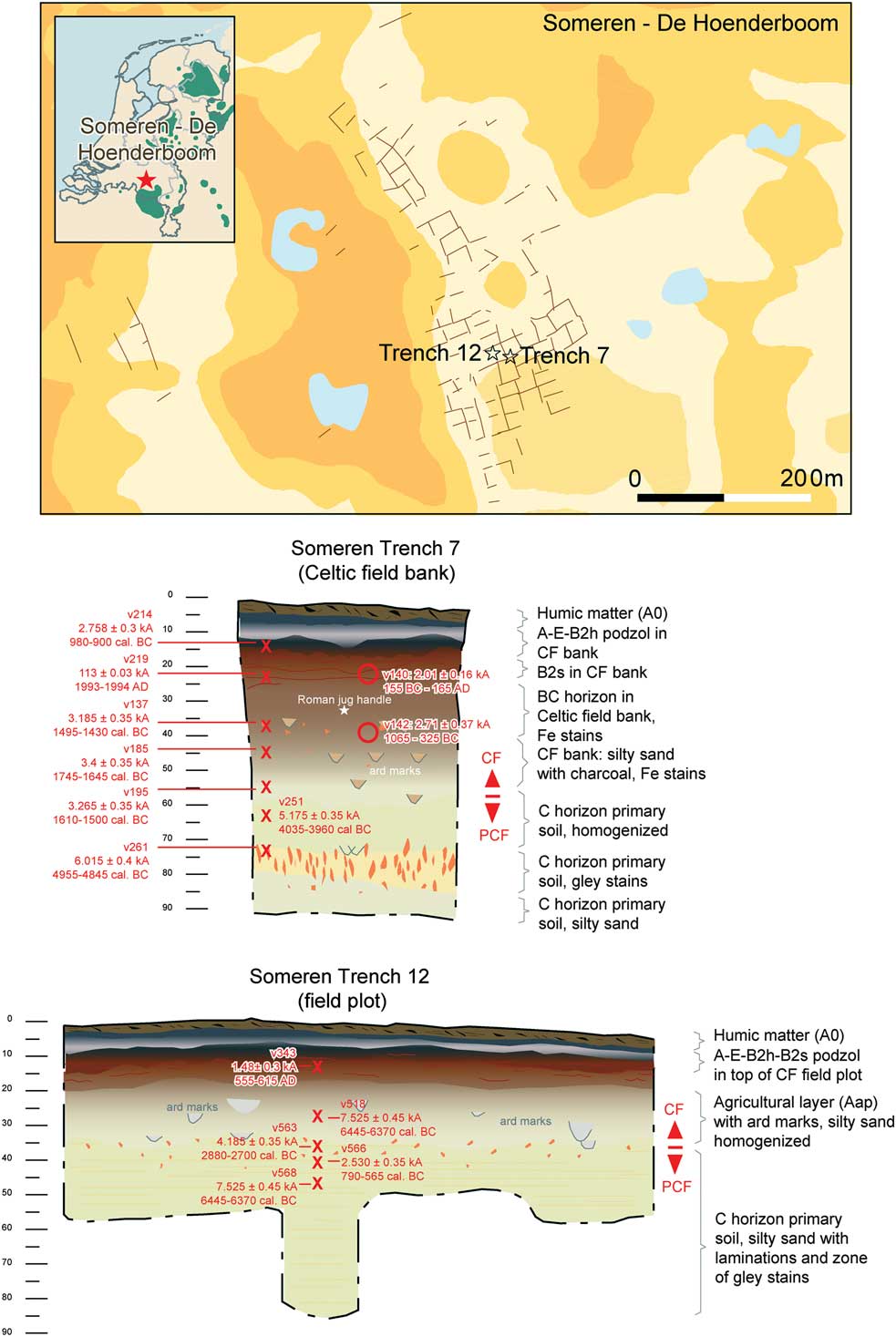

Someren-De Hoenderboom

As for the site of Someren-De Hoenderboom (Fig. 7), no prior research into the age and use-history of this Celtic field had been undertaken; it had previously been (mis-?)identified as an urnfield (Hermans Reference Hermans1865, 89; Kortlang & Van Ginkel Reference Kortlang and Ginkel2016, 89), and LiDAR identification of the banks did not take place until 2011 (Arnoldussen Reference Arnoldussen2013, 62). Fieldwalking campaigns in 1988 and 2001 yielded some Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age potsherds (Van der Gaauw Reference Gaauw1989, cat. no. 6).

Fig. 7 Overview and geogenetic interpretation of Celtic field banks at Someren-De Hoenderboom. The locations of the OSL samples are indicated as red circles; those of AMS samples are marked with red crosses

Between 2012 and 2014, a series of targeted excavations of the Celtic field banks and fields took place. For a 55 cm high bank (trench 7), a strategy of OSL dating combined with AMS dating of the section was undertaken. The two lowermost AMS dates (Fig. 7, trench 7) indicate that (a) the primary underlying soil had been decapitated by the later Celtic field tillage, and (b) residual charcoal indicated human activity in the 5th and 4th millennia bc. The three dates obtained from the base of the anthropogenic Celtic field bank upwards suggest human activity in the 18th–15th centuries bc. This tallies well with the oldest OSL dates from Zeijen (trenches 4 & 5; Fig. 6), but it would be too simple to postulate that these banks also evolved from the start of the Middle Bronze Age. The fact that the lowermost OSL date of trench 7 dates to 1065–325 bc, while being stratigraphically at the same height as the topmost two Middle Bronze Age AMS dates, indicates that in the process of bank aggradation Middle Bronze Age charcoal was still incorporated higher into the banks. Ploughmarks oriented obliquely to the field system, discovered at various depths within the banks (Arnoldussen et al. Reference Arnoldussen, Schepers and Maurer2016), could suggest ploughing episodes that occurred after prolonged fallow periods and indicate the use of a heavy ard for breaking the sod (Groenman-Van Waateringe Reference Groenman-van Waateringe1980, 363; McIntosh Reference McIntosh2009, 120). This infrequent but deeper type of ploughing presumably facilitated the upward displacement of older charcoal. Probably an initial Middle Bronze Age phase of cultivation (which did not necessarily involve banks) was at the Middle to Late Bronze Age transition followed by a system that did involve net sediment input to the banks – thus causing vertical bank aggradation. Such a developmental trajectory may have applied to Zeijen Bank 3 as well, where the lowermost part of the bank may also represent a homogenised mixing of the primary soil horizons due to Bronze Age agriculture (Fig. 6).

Apart from an obvious recent intrusion (Someren v219; AMS ad 1993/1994), the topmost AMS dates of trench 7 at Someren may indicate bank formation well into the Iron Age. The topmost OSL date for that bank (at 25 cm depth) even spans the period 165 bc–ad 165. This means that bank formation may have continued into the first two centuries of the Roman era. The fragment of a handle of a Roman jug (possibly of Stuart 130 type; Stuart Reference Stuart1977, 54) datable to the 1st or 2nd century ad was recovered at a depth of 35 cm and indeed provides confirmation of such longstanding bank formation. The majority of the pottery recovered in sieving the sediment from several Celtic field banks at Someren, however, dated from the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age (c. 1000–500 bc).

As the dates obtained for the Someren Celtic field bank present a chronostratigraphic accumulative record due to a net input of sediment (through a combination of uprooted field weeds [cf. Jankuhn Reference Jankuhn1958, 181], manure, and compost; Arnoldussen & vander Linden Reference Arnoldussen and Linden2017; Fokkens Reference Fokkens1998, 121), a second series of AMS dates was undertaken for the adjacent field plot (trench 12), where stratification of ard-marks also proved net sediment input. In the field plot, however, no chronostratigraphy was preserved (owing to more frequent ploughing?). The scattered dates suggest human activity around the 7th and 3rd millennia bc and during the Early Medieval period, with only a single date (790–565 cal bc; GrA-64734: Table 1) that may actually pertain to the Celtic field’s use-phase proper (Fig. 7, trench 12).

Table 1 all dates (including field-plot locations & outliers)

References: (1) Wallinga & Versendaal Reference Wallinga and Versendaal2013a, 6; (2) Spek et al. Reference Spek, Groenman-van Waateringe, Kooistra and Bakker2003, 165; (3) Voskuilen et al. Reference Voskuilen, Reimann and Wallinga2016, 12; (4) this publication; (5) Wallinga & Versendaal Reference Wallinga and Versendaal2013b, 6; (6) Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014, 66; (6) Arnoldussen not yet published

Wekerom-Lunteren

The presence of a field system from later prehistory at Wekerom had been known since the 19th century, when the curator of the Leiden National Museum of Antiquities, Janssen (Reference Janssen1848, 11), had parts of it mapped (Brongers Reference Brongers1976, 123, fig. 4). In 1939–1941 another curator of the same museum, Frans C. Bursch, dug trial trenches in several of the fields in the north-westernmost part of the Wekerom Celtic field (Fig. 5, A; Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014, 14, fig. 7). Unfortunately, no stratigraphic relation between houses and banks was recorded, and for much of the recovered pottery assemblage (mostly Middle Iron Age; ibid., 18), it is unclear to what house or trench feature it belonged.

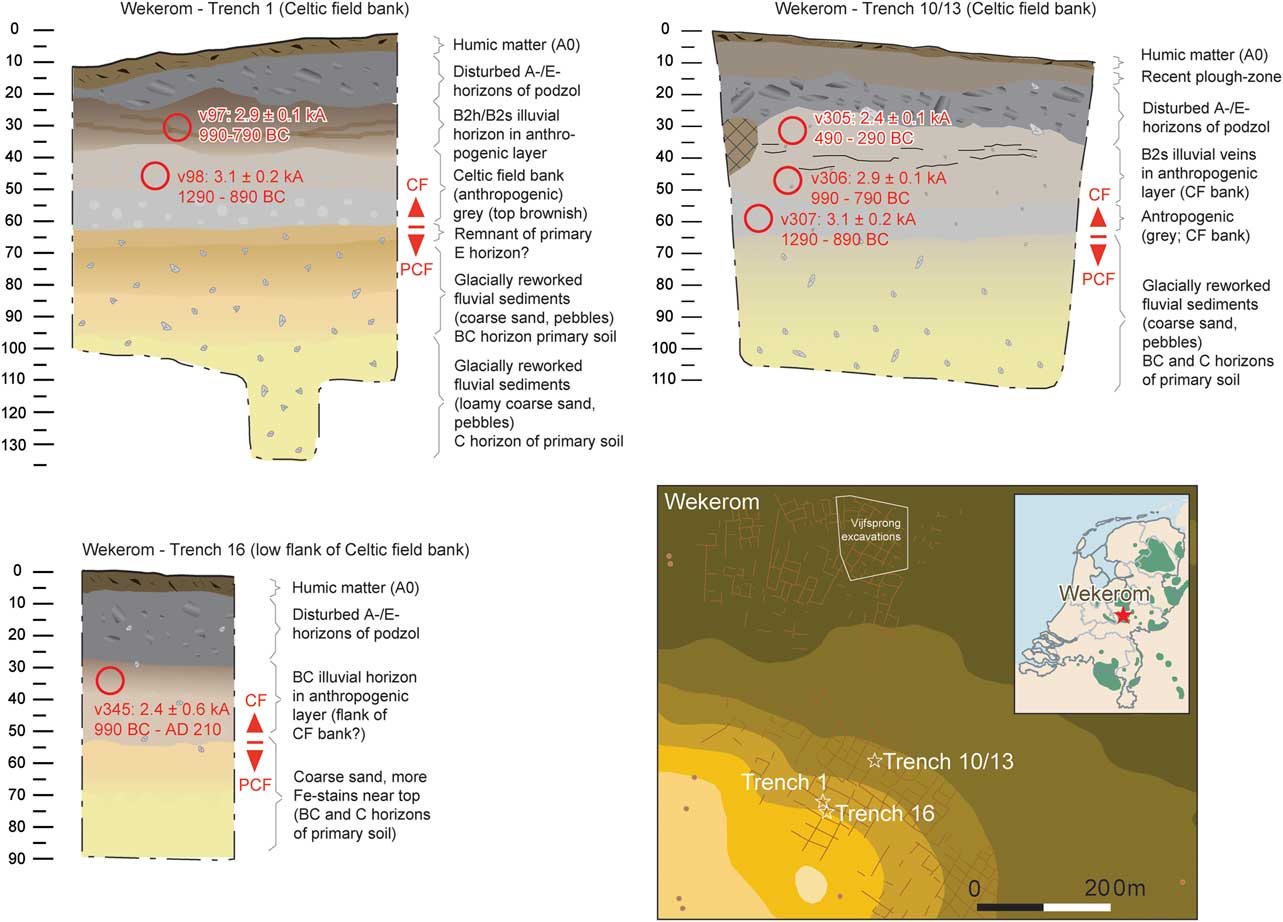

In 2012, various field plots and banks of the Wekerom-Lunteren Celtic field were excavated as part of the Groningen Celtic field programme (Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014). Here, too, a campaign of OSL dating was undertaken to establish a chronology for bank construction. The lowermost OSL dates for the banks in trenches 1 and 10/13 both spanned the period of 1290–890 bc (Fig. 8; Wallinga & Versendaal Reference Wallinga and Versendaal2013a, 6), indicating bank construction from the 13th–10th centuries bc onwards. At both banks, the OSL sample situated c. 10–15 cm higher in the bank yielded a date of 990–790 bc (ibid.; Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014, 66), which hints at very slow accumulation rates for the banks (cf. Klamm Reference Klamm1993, 44; Zimmermann Reference Zimmermann1995, 293; Gerritsen Reference Gerritsen2003, 175, 177). This is confirmed by the topmost OSL date of trench 10/13, which was again situated c. 15 cm higher and was dated to the 5th or 4th century bc. As a very crude ‘rule of thumb’ – as it assumes growth to be continuous and linear – the Wekerom OSL dates suggest an accumulation rate in the order of 30 years per cm for these Celtic field banks (Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014, 66; 92). Above the topmost sample in trench 10/13 still c. 25 cm of bank remained (which was avoided for fear of contamination), which again suggests that – as at Someren – bank aggradation may have continued into the Roman period.

Fig. 8 Overview and geogenetic interpretation of Celtic field banks at Wekerom (after Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014). The locations of the OSL samples are indicated as red circles

Westeinde-Noormansveld

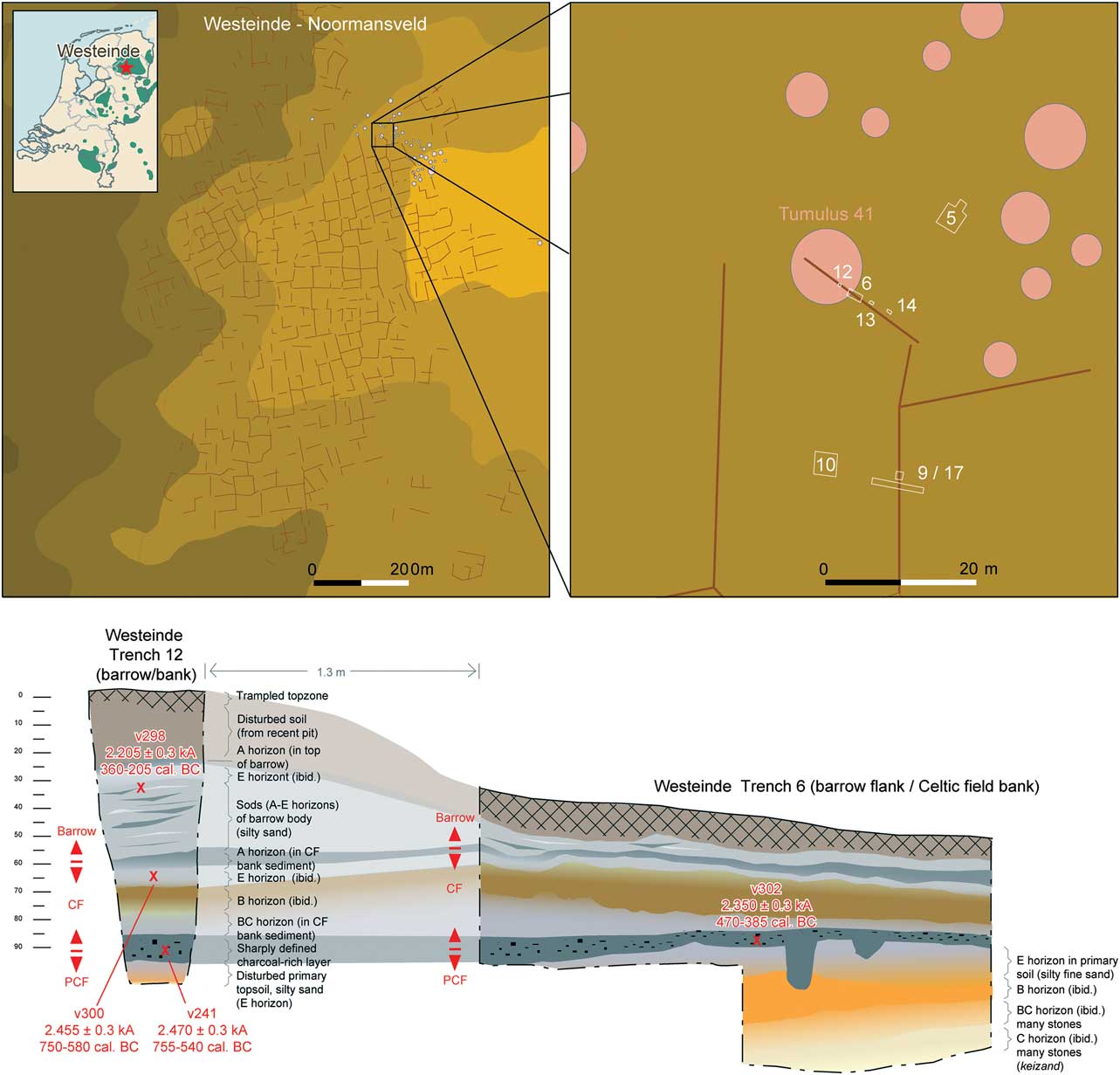

The Celtic field of Westeinde-Noormansveld – like that of Someren – was largely unknown prior to the availability of LiDAR altimetry data in 2010. In hindsight, the banks around a single field plot had already been mapped in 1999, when restoration of the barrow group known locally as ‘Noormansveld/Boerdennen’ was undertaken (Fig. 9; Van Zeist Reference Zeist1955; Datema Reference Datema2003). It was only through the availability of LiDAR imagery that the full extent (over 34 ha) of the Westeinde Celtic field became clear (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9 Overview and geogenetic interpretation of Celtic field banks and overlying barrow (Tumulus 41) at Westeinde-Noormansveld. The positions of the AMS samples are marked by red crosses

Between 2014 and 2017, various barrows, banks, and field plots of the Westeinde Celtic field were investigated as part of the Groningen University Archaeology Field School. Particular attention was given to the vicinity of Tumulus 41, which appeared to be connected to a Celtic field bank. The possible stratigraphic relation between the barrow and the field embankment was investigated by means of a series of small trenches (Fig. 9, trenches 12–14). Trench 12 was a narrow, deep cut that utilised a modern looting pit dug into the barrow, so as not to disturb the mound even more. The sections showed that Tumulus 41 had been constructed on top of the Celtic field bank. An AMS-dated fragment of charcoal from the barrow places its construction in or after the 4th or 3rd century bc – a scenario not unlike that of the Late Iron Age cinerary barrow built on top of the bank at Zeijen (supra; Van Giffen Reference Giffen1949, 119, fig. 20). From the Celtic field bank underlying Tumulus 41, two radiocarbon dates were obtained that suggest bank development in the 8th–6th centuries bc. A charred fragment from the charcoal-rich deposit at the base of the Celtic field bank in trench 6 was dated to the c. 5th century bc (Fig. 9), hinting at a somewhat later start of bank construction here. As this sample was taken from an area that also showed some post-holes, contamination from more recent activities cannot be ruled out (and, given that a sample from the same layer in trench 12 was dated to 755–540 cal bc (GrA-62653; Table 1), this may indeed be the most likely scenario).

Conclusion of the dating programme

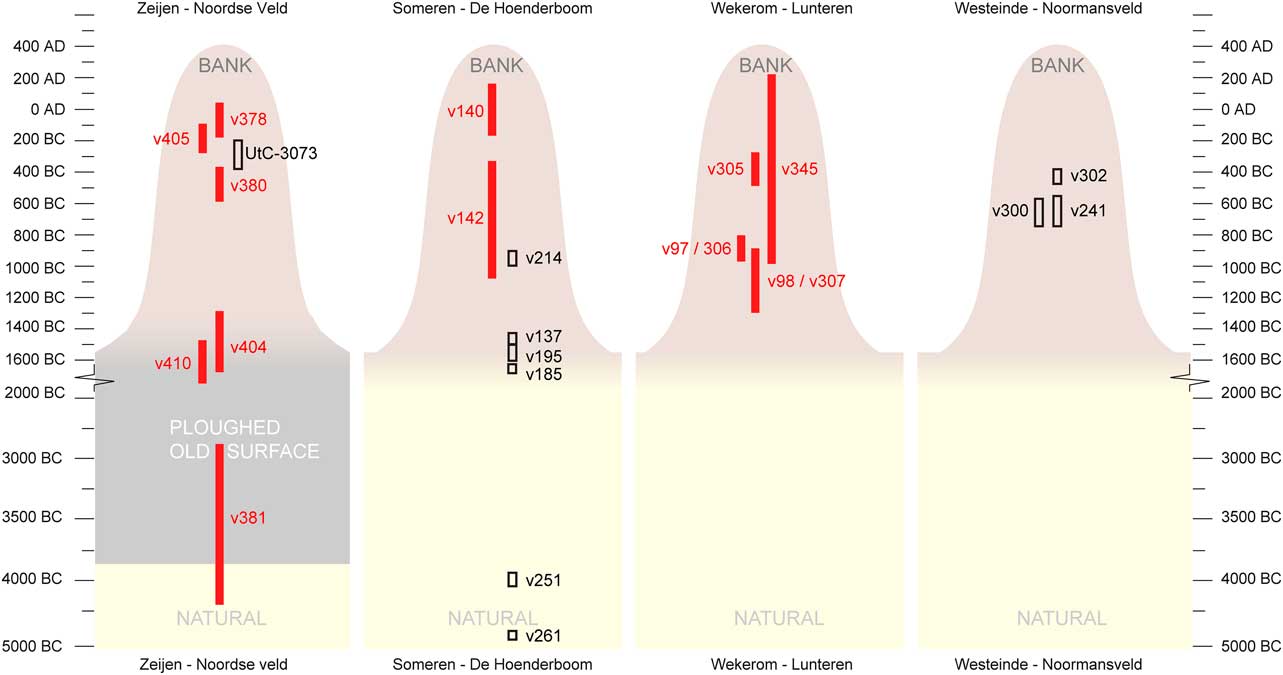

As samples from the lowermost and uppermost parts of the banks are less suitable for OSL dating because of the risk of contamination with older (glacial sediments underlying the banks) or younger (modern surface) sediments, the newly obtained ages can only roughly frame the main period of use. We should also allow for even longer use to be reflected in the undated lower and topmost parts of the banks. Nevertheless, bank development seems to have been taking place by around the 13th–10th centuries bc, at the close of the Dutch Middle Bronze Age-B (1500–1000 cal bc). Only the radiocarbon date for the charcoal layer at Westeinde trench 6 hints at later (5th century bc) initial bank development, but potential contamination from nearby features poses an interpretative risk there. Judging by the OSL samples, but finding confirmation in the AMS dates, it appears that bank formation was an ongoing process throughout the Late Bronze Age (1000–800 cal bc) and Iron Age (800–12 cal bc).

Also, it is important to stress that in all the banks dated by OSL a distinct chronostratigraphy was observed: invariably the oldest samples within a given bank were lowermost in position, with progressively younger dates obtained for samples higher up in the banks (Someren v219 with a date of ad 1993/1994 being an obvious recent contamination; Fig. 10 & Table 1). This indicates a gradual, but also tremendously long term genesis of the Celtic field banks – this tallies well with low intensity sediment displacement and also with recurrent agricultural activities such as the clearing and weeding of fields, as postulated above on the basis of the contents of the banks. As regards the end of Celtic field farming, the OSL dates of Zeijen, Wekerom, and Someren all suggest continued bank aggradation into the Roman era (Fig. 10). The topmost OSL date from Someren trench 7 and the Roman jug handle suggest that the processes contributing to bank building continued there into the 2nd century ad. However, not all banks continued to grow: at Zeijen and Westeinde, there is clear evidence that in the Late Iron Age, barrows were designedly constructed on top of some Celtic field banks, whereas other banks at those sites presumably retained their (agricultural) function.

Fig. 10 Dates from banks in four Celtic fields, by site and stratigraphic context (omitting outlier Someren v219); note the discontinuous temporal y-axis. See Table 1

IMPLICATIONS: THE NETHERLANDS’ MOST STABLE AGRICULTURAL LANDSCAPE

The chronostratigraphies preserved in the Dutch Celtic field banks testify to an agricultural sustainability of use of unprecedented time-depth. For Wekerom and Zeijen, the relations between bank aggradation and documented time-depths indicate that this system was in place for at least 400–600 years (Arnoldussen & Scheele Reference Arnoldussen and Scheele2014, 92), but a use-life of several centuries more is not at all improbable (considering the evidence for continued bank development above the highest dated samples). No other agricultural system or landscape from the Netherlands is known that shows such a traditionality and sustainability across the better part of a millennium. That said, this long term traditionality of form may mask a multitude of shifts and changes in the underlying agricultural regimes, which as yet have remained invisible because of the few datasets and dates available (cf. Fig. 4).

In this paper, the inception of Celtic field development has been dated several centuries earlier (ie 13th–10th centuries bc) than had been traditionally assumed (eg, Harsema Reference Harsema2005, 543; Kooistra & Maas Reference Kooistra and Maas2008, 2319). Whereas the rise of prehistoric field systems in the British Isles is frequently dated to the Middle Bronze Age (Klamm Reference Klamm1993, 82; Bewley Reference Bewley2003, 82; Yates Reference Yates2007, 22, 27; Wickstead Reference Wickstead2007, 44; Sharples Reference Sharples2010, 36–41; Ten Harkel et al. Reference Harkel, ten, Franconi and Gosden2017, 419), such an early start had not yet been argued for the continental field systems with earthen banks. By the Late Bronze Age, most of the field systems in southern England fell into disuse, with no evidence for new examples in Iron Age Wessex (Sharples Reference Sharples2010, 43). This may mean that, both in terms of an early start and of longevity (eg, the Dartmoor field systems may very well have functioned for six or seven centuries; Bewley Reference Bewley2003, 82, cf. Johnston Reference Johnston2005, 16; Reference Johnston2013; Fyfe et al. Reference Fyfe, Brück, Johnston, Lewis, Roland and Wickstead2008), the Dutch raatakkers do have equivalents across the Channel, albeit that the Dutch counterparts demonstrably continued in use in both the Iron Age and Roman period.

Such an early dating of the Dutch Celtic fields may resolve a previously salient discrepancy in Dutch grand narratives of prehistoric (agri)cultural landscape development: the assumed (Late Bronze Age to) Iron Age date for the Dutch raatakkers implied that a chronological gap existed between the parcelled landscapes of the Dutch Middle Bronze Age-B (c. 1500–1000 cal bc) and those of the Iron Age (800–12 cal bc). The scale and spatial syntax of Dutch (agri)cultural landscape compartmentalisation documented in wetlands as ditches (eg, Lohof & Roessingh Reference Lohof and Roessingh2014) or fences (eg, Arnoldussen Reference Arnoldussen2008, 421–3) during the Middle Bronze Age-B were supposedly lost or rendered archaeologically invisible around the Late Bronze Age (c. 1000–800 cal bc), only to re-appear in new landscapes (upland settings) during the Iron Age with a similar spatial grammar of linearity and perpendicularity. The present reading of the data instead suggests that Dutch Celtic fields may, in their (a) devotion to compartmentalisation, (b) spatial grammar of linearity and perpendicularity, and (c) extensive spatial scale, be legitimate heirs or successors to a final Middle Bronze Age system of agricultural landscape layout.

The centuries-long use-life of Dutch Celtic fields propounded in this paper was inferred primarily from the long continuation of an agricultural strategy in which soil from the fields ended up in the banks. This must therefore have been a process vital and inherent to the agricultural regime in question. Dumping of uprooted weeds, or processes by which topsoil from the fields was mixed on the banks with a refuse-manure mix derived from the settlement sites (cf. Bradley Reference Bradley1978, 267; Kroll Reference Kroll1987, 113) are both strong candidates. Regardless of which, or what combination, of these processes was the main stable force, the stability and traditionality of bank formation should not be used as an argument for a wholly static and unchanging agricultural regime on the time-scale of centuries. At present, however, the dataset is still too sparse in terms of vertical (ie diachronic) and horizontal (ie synchronous differences in use between field plots) distribution, as well as in absolute numbers (ie numbers of Celtic fields studied) to allow much extrapolation of the data on crops grown, fallow cycles, or tillage and manuring strategies. What is important, however, is the notion put forward here that the banks around field plots provide chronostratigraphic repositories able to answer such questions in the future through more targeted fieldwork.

Also, the presented data suggests that over the prolonged use-life of Dutch raatakkers, the ways in which communities of raatakker users perceived these landscapes have differed. House sites from the earlier (13th–10th centuries cal bc) phases of Celtic field use are lacking, leaving us with a tantalizing discrepancy between the early OSL dates obtained for the start of the Celtic field regime (final Middle Bronze Age-B to Late Bronze Age) and the recovered ceramics (Late Bronze Age/Early Iron Age) on the one hand, and the uncovered house sites within them (solely Iron Age) on the other. If the layout of the Celtic field system was indeed written onto the landscape (with fencing?) before the Iron Age, where were the house sites of those periods situated (cf. Ten Harkel et al. Reference Harkel, ten, Franconi and Gosden2017, 420)? One could argue that it is mere chance that none of these has, as yet, been identified (given the few sites investigated and small areas uncovered in such excavations; but see Fig. 5); however, more probably, final Middle Bronze Age-B to Late Bronze Age perceptions of ideal settlement locations with regard to the fields differed from those of later Iron Age communities. The scarcity of pottery from the final Middle Bronze Age and early Late Bronze Age may be explained if the tradition of adding settlement debris to the manuring mix of dung and possibly sods reflects a practice adopted only later on, from the Late Bronze Age onwards (cf. Fokkens Reference Fokkens1998, 120).

Similarly, the fact that Middle and Late Iron Age house sites frequently are found overlapping Celtic field banks signals yet another shift in perception (cf. Becker Reference Becker1971, 98, 101, fig. 21): in those periods, living amidst – or even on top of – Celtic field banks was considered unproblematic, and possibly even desirable. It is striking that at this time disused urnfields were also considered proper settlement sites (Arnoldussen & Albers Reference Arnoldussen and Albers2015), which indicates that around the Middle–Late Iron Age transition shifted perceptions of suitable settlement locations were substantial and pervasive. The fact that in the Late Iron Age some banks were capped by barrows (eg, at Zeijen and Westeinde, cf. Bradley Reference Bradley1978, 267) again signals a fluidity of perception of these initially primarily agricultural areas. Evidently, the long standing bank formation does not belie the Celtic field regime’s dynamics at smaller social, spatial, and temporal scales (cf. Becker Reference Becker1971, 104). There will have been considerable variation in ‘what crops were grown where’ through the years, and Celtic field users (households or larger social clusters, cf. Bewley Reference Bewley2003, 84; Gerritsen Reference Gerritsen2003, 179; Johnston Reference Johnston2005, 13; Wickstead Reference Wickstead2007, 46–7) may have made individual decisions on the use of particular plots (eg, crops, fallow, grassland) at different points in time. Similarly, chosen durations of fallow cycles or the addition of new areas to existing Celtic fields both provided additional variability to the temporal (agricultural cycles) and spatial (extension) dimensions of Celtic fields in late prehistory.

Considering this high potential for stochastic variability on the spatio-temporal scale of the Celtic field user communities (supra), their morphological uniformity across the various geogenetic regions in the Netherlands remains striking (cf. Fig. 2). Across the geogenetic regions, the tenurial regimes led to quite similar morphological outcomes in prehistory, combining areas of more regular parcelling in the form of embanked fields with zones of somewhat less regular division (cf. English Reference English2013, 134–53), albeit still conforming to the overall dominant axes of orientation (cf. Løvschal & Holst Reference Løvschal and Holst2014, 8; Brongers Reference Brongers1976, 41). Without downplaying the evident potential for equifinality and inter-site variation in such morphological patterns, it is striking to see what is not there. Fundamentally different systems of land allotment (cf. Jankuhn Reference Jankuhn1958, 174–5; Bradley Reference Bradley1978, 268; Wickstead Reference Wickstead2007, 108; Gosden Reference Gosden2013; Løvschal Reference Løvschal2014, 722–31) – such as larger reclamations of varying shapes, strip-parcelling, or radial or circular bank configurations – are absent in the Dutch corpus of raatakkers, which are mostly rectilinear with quite standardised plot sizes, in parts more aggregate and in others more co-axial in nature. Evidently, those elements of the agricultural system that contributed to the form (eg, initial rectilinear wattle fencing) and inertia (eg, weed dumping or topsoil stripping/manuring leading to bank aggradation) of the raatakker field boundaries were shared or similar across different geogenetic regions. These supra-regional similarities reflect a sustainable, successful, and widely shared interplay of boundary conceptualisation, agricultural use, and boundary materialisation which for centuries remained relevant to the farming communities that had initiated and maintained the system’s enduring physicality.

Acknowledgements

The Groningen Celtic field programme is indebted to the following organisations for practical, financial, or scientific support: Provincie Drenthe, Gemeente Westerveld, Gemeente Vries, Staatsbosbeheer, Stichting Natuurmonumenten, Provincie Gelderland, Gemeente Ede, Provincie Noord-Brabant, Gemeente Someren, Rijksdienst voor het Cultureel Erfgoed, Nationaal Park De Meinweg, and Stichting Nederlands Museum voor Anthropologie en Praehistorie. Xandra Bardet corrected the English for this paper.